A Mixed-Methods Case Report on Oral Health Changes and Patient Perceptions and Experiences Following Treatment at the One Smile Research Program: A 2-Year Follow-Up

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Methods

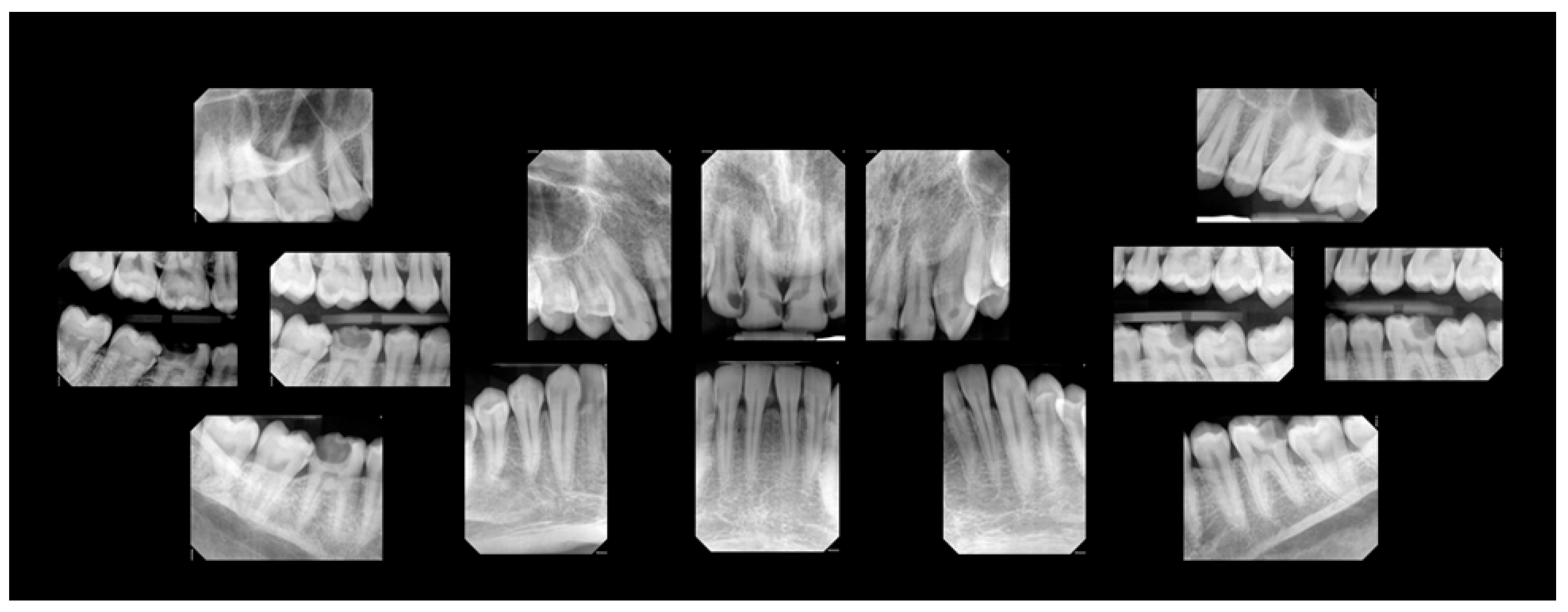

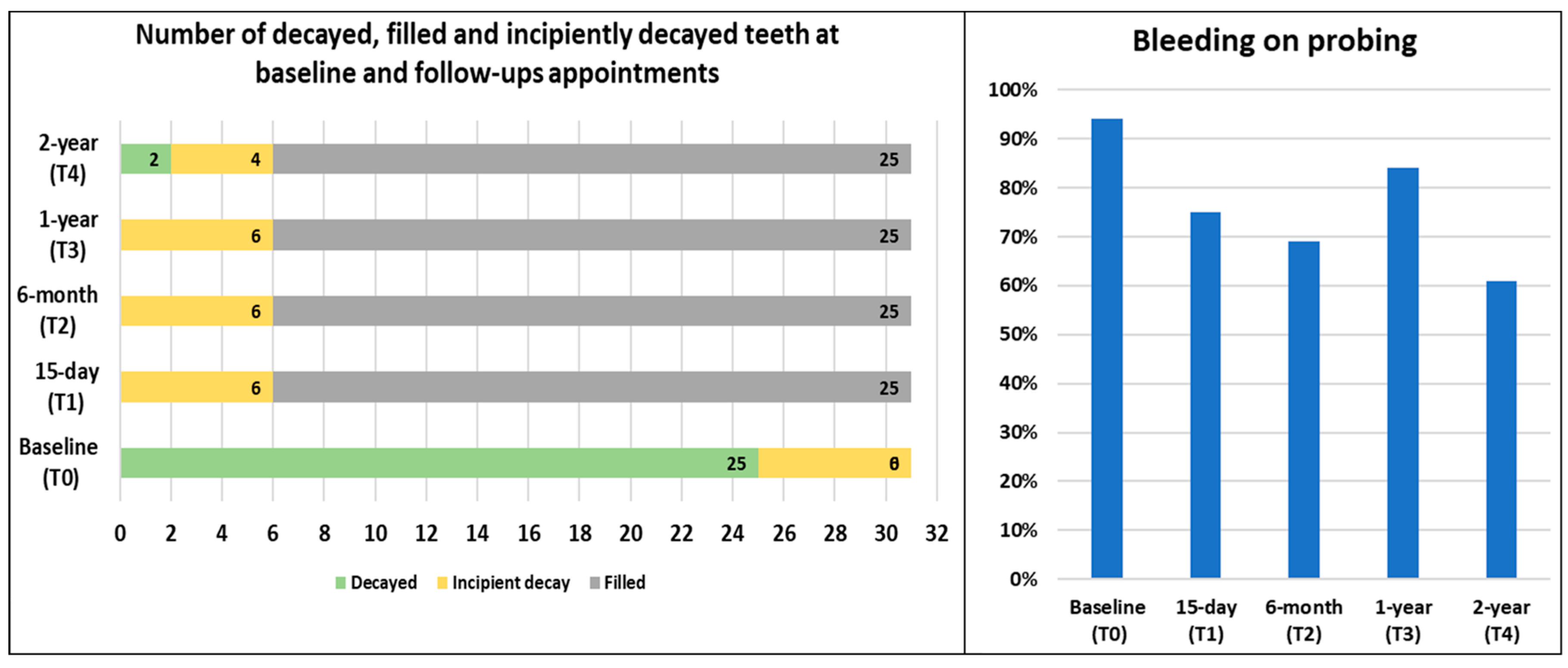

2.1.1. Baseline Exam

2.1.2. Dental Treatment

2.1.3. Self-Reported Questionnaire

2.1.4. Qualitative Findings

Ease of Admission

Just went on Google. Searched up like U of T Green Shield Clinic, I think it was at first. Like went, selected the website and went in. I could not sign up at first because all the spaces were taken, but I had to wait, like three months I think, and then I signed up.

Kindness of the Staff

Where I come from like in Europe, I guess, like the doctors are more rude. Like, I guess would be the term… People [providers] might say things, things that you haven’t done [reprimanding the patient] and stuff like that. In my experience, this is just amazing cause the people [providers at OSP] are too nice… Oh, they were very helpful and nice, right? I mean, I learnt things that I did not know about, of course. Like flossing, for example. Like, [I] never even knew what that was until I got here [dental clinic]… [Patients in need of public dental care] like their incomes are lower. So, obviously, they feel better if I tell them what they get when they sign up and the people are nice, [and] stuff like that.

Improvement in Overall Well-Being

Like, the positives are, like way more, like, they outnumber [the negatives]… But no negatives I can think about really, but some pain, but I guess that’s normal, I guess, at first… Well, the thing I thought was actually [more beneficial is] being able to interact with people, not feeling inferior or insecure, I guess. It’s like people have better teeth or perfect teeth, whatever the case may be. That’s the biggest thing for sure

People coming from abroad, like war-torn places, for example, like asylum seekers, people below a certain amount of income, like $70,000 or $60,000, [should be granted public insurance]… I feel like the things should be covered should be like the very important things root canals, fillings, crowns… Like cleanings, I mean, sure if it’s like possible but definitely the molar damaging things like fillings and RCTs and even braces… I mean the perfect place I feel like, is to be under the umbrella of health care system that everything should be free. But obviously, it will cycle slowly, it should be like the low-income people and, of course, the asylum seekers. Like I said, but in the perfect world, I feel like everyone should have access to it for sure, like other things that are a part of the health care system.

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PIDAQ | Psychosocial Impact of Dental Aesthetic Questionnaire |

| MDAS | Modified Dental Anxiety Scale |

| RSES | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale |

| SFQ | Social Functioning Questionnaire |

References

- World Dental Federation. FDI’s Definition of Oral Health. Available online: https://www.fdiworlddental.org/fdis-definition-oral-health (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Canada Health Act, RSC 1985, c C-6. Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-6/page-1.html (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Quiñonez, C. The Politics of Dental Care in Canada; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Canadian Dental Association. Understanding Co-Payment. Available online: https://www.cda-adc.ca/en/oral_health/talk/copayment.asp (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Abdelrehim, M.; Ravaghi, V.; Quiñonez, C.; Singhal, S. Trends in self-reported cost barriers to dental care in Ontario. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, W.M.; Williams, S.M.; Broadbent, J.M.; Poulton, R.; Locker, D. Long-term dental visiting patterns and adult oral health. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshy, V. Action Research for Improving Practice: A Practical Guide; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Onghena, P.; Maes, B.; Heyvaert, M. Mixed methods single case research: State of the art and future directions. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2019, 13, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskarada, S. Qualitative case study guidelines. Qual. Rep. 2014, 19, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klages, U.; Claus, N.; Wehrbein, H.; Zentner, A. Development of a questionnaire for assessment of the psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics in young adults. Eur. J. Orthod. 2006, 28, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, J.T.; Edwards, J.C. Psychometric properties of the modified dental anxiety scale: An independent replication. Community Dent. Health 2005, 22, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE). Available online: https://www.apa.org/obesity-guideline/rosenberg-self-esteem.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Tyrer, P.; Nur, U.; Crawford, M.; Karlsen, S.; McLean, C.; Rao, B.; Johnson, T. The Social Functioning Questionnaire: A rapid and robust measure of perceived functioning. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2005, 51, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crotty, M. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, M. The role of theory in qualitative health research. Fam. Pract. 2010, 27, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, K.R.; Johnston, C.A. Advocating for behavior change with education. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2018, 12, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Dental Surgeon of Ontario. Standards, Guidelines and Resources. Available online: https://www.rcdso.org/standards-guidelines-resources (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Paisi, M.; Baines, R.; Worle, C.; Withers, L.; Witton, R. Evaluation of a community dental clinic providing care to people experiencing homelessness: A mixed methods approach. Health Expect. 2020, 23, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.C.; Chi, D.L.; Schwarz, E.; Milgrom, P.; Yagapen, A.; Malveau, S.; Chen, Z.; Chan, B.; Danner, S.; Owen, E.; et al. Emergency department visits for nontraumatic dental problems: A mixed-methods study. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Canadian Institute for Health Information. National Health Expenditure Trends. In Data Tables-Series, A; The Canadian Institute for Health Information: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, J.; Singhal, S.; Ghoneim, A.; Proaño, D.; Moharrami, M.; Kaura, K.; McIntyre, J.; Quiñonez, C. Environmental Scan of Publicly Financed Dental Care in Canada: 2022 Update; Dental Public Health, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022; Available online: https://caphd.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Canada-Dental-environmentscan-UofT-20221017.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Government of Canada. Canadian Dental Care Plan. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/dental/dental-care-plan.html?utm_campaign=hc-sc-canadian-dental-care-plan-24-25&utm_source=ggl&utm_medium=sem&utm_content=ad-text-en&adv=611850&utm_term=canada+dental+coverage&gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAjwvKi4BhABEiwAH2gcw6ReOk8pauoW4Golf9Gkr16tiBBEYmzq6FaV8FDZUnxMlTsgl7gmQhoCLVEQAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Ramraj, C.; Quiñonez, C.R. Self-reported cost-prohibitive dental care needs among Canadians. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2013, 11, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelrehim, M.; Singhal, S. Is private insurance enough to address barriers to accessing dental care? Findings from a Canadian population-based study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehmoobadsharifabadi, A.; Singhal, S.; Quiñonez, C. Investigating the “inverse care law” in dental care: A comparative analysis of Canadian jurisdictions. Can. J. Public Health 2016, 107, e538–e544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groves, R.R. Dental Fitness Classification in the Canadian Forces. Mil. Med. 2008, 173 (Suppl. 1), 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

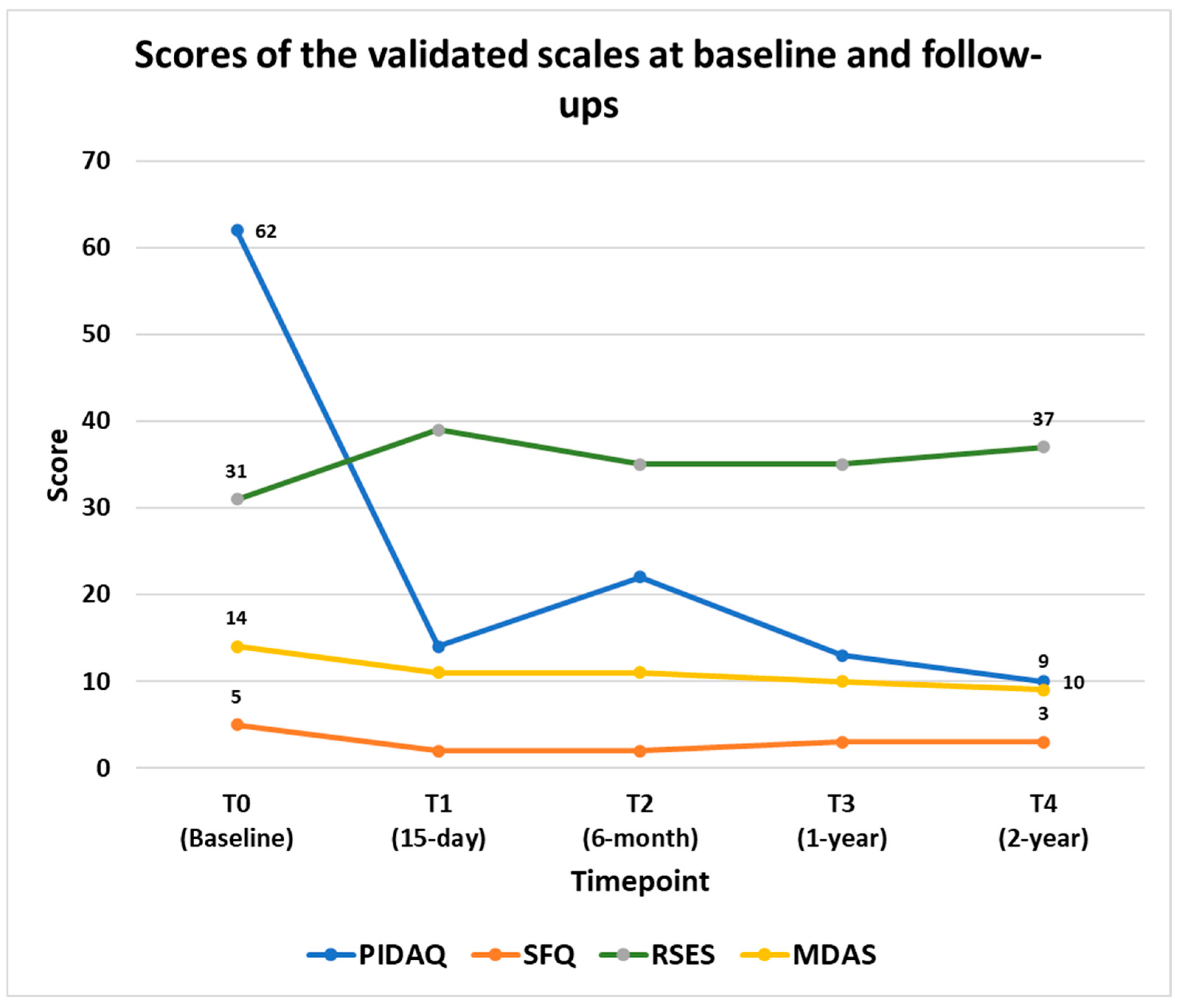

| Validated Scales | Score Ranges | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial impact of dental treatment (PIDAQ) | 0 to 92 | Lower scores indicate a positive impact on psychosocial well-being related to dental treatment. |

| Social functioning questionnaire (SFQ) | 0 to 24 | Lower scores indicate better social functioning. |

| The Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES) | 10 to 40 | Higher scores indicate better self-esteem. |

| The modified dental anxiety scale (MDAS) | 6 to 30 | Lower scores indicate less anxiety |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdelrehim, M.; Huang, Z.; Martine, C.; Pal, I.; Kaura, K.; Aggarwal, A.; Singhal, S. A Mixed-Methods Case Report on Oral Health Changes and Patient Perceptions and Experiences Following Treatment at the One Smile Research Program: A 2-Year Follow-Up. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15080136

Abdelrehim M, Huang Z, Martine C, Pal I, Kaura K, Aggarwal A, Singhal S. A Mixed-Methods Case Report on Oral Health Changes and Patient Perceptions and Experiences Following Treatment at the One Smile Research Program: A 2-Year Follow-Up. Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(8):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15080136

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdelrehim, Mona, ZhuZhen (Hellen) Huang, Christiana Martine, Imon Pal, Kamini Kaura, Anuj Aggarwal, and Sonica Singhal. 2025. "A Mixed-Methods Case Report on Oral Health Changes and Patient Perceptions and Experiences Following Treatment at the One Smile Research Program: A 2-Year Follow-Up" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 8: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15080136

APA StyleAbdelrehim, M., Huang, Z., Martine, C., Pal, I., Kaura, K., Aggarwal, A., & Singhal, S. (2025). A Mixed-Methods Case Report on Oral Health Changes and Patient Perceptions and Experiences Following Treatment at the One Smile Research Program: A 2-Year Follow-Up. Clinics and Practice, 15(8), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15080136