Collagen Injections for Rotator Cuff Diseases: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

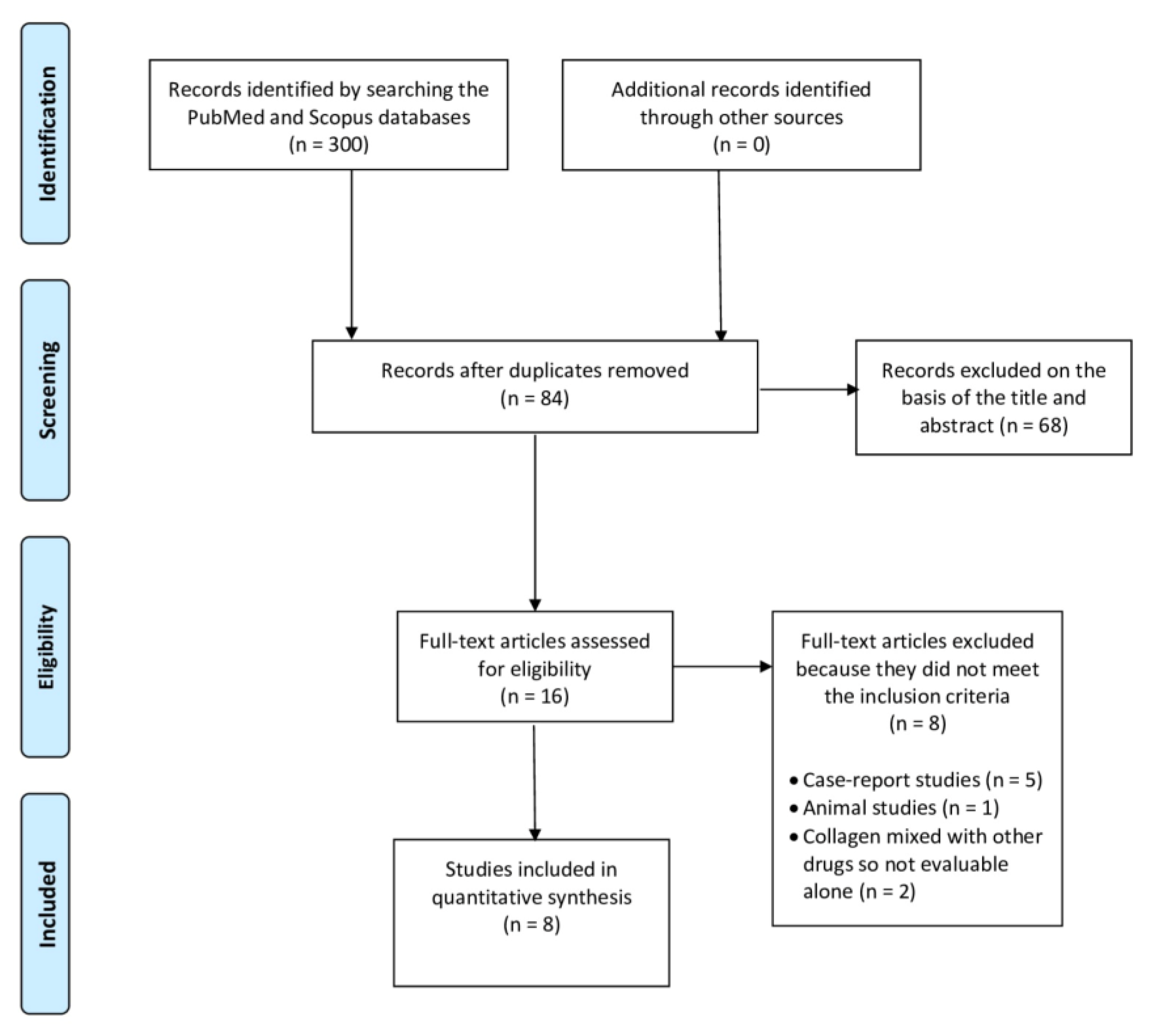

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dugas, J.R.; Campbell, D.A.; Warren, R.F.; Robie, B.H.; Millett, P.J. Anatomy and dimensions of rotator cuff insertions. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2002, 11, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nho, S.J.; Yadav, H.; Shindle, M.K.; Macgillivray, J.D. Rotator cuff degeneration: Etiology and pathogenesis. Am. J. Sports Med. 2008, 36, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffulli, N.; Longo, U.G.; Berton, A.; Loppini, M.; Denaro, V. Biological factors in the pathogenesis of rotator cuff tears. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2011, 19, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, U.G.; Berton, A.; Papapietro, N.; Maffulli, N.; Denaro, V. Epidemiology, genetics and biological factors of rotator cuff tears. Med. Sport. Sci. 2012, 57, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Di Iorio, A.; Del Prete, C.M.; Barassi, G.; Paolucci, T.; Tognolo, L.; Fiore, P.; Santamato, A. Efficacy of Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Lavage and Biocompatible Electrical Neurostimulation, in Calcific Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy and Shoulder Pain, A Prospective Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuè, G.; Masuzzo, O.; Tucci, F.; Cavallo, M.; Parmeggiani, A.; Vita, F.; Patti, A.; Donati, D.; Marinelli, A.; Miceli, M.; et al. Can Secondary Adhesive Capsulitis Complicate Calcific Tendinitis of the Rotator Cuff? An Ultrasound Imaging Analysis. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farì, G.; Megna, M.; Ranieri, M.; Agostini, F.; Ricci, V.; Bianchi, F.P.; Rizzo, L.; Farì, E.; Tognolo, L.; Bonavolontà, V.; et al. Could the Improvement of Supraspinatus Muscle Activity Speed up Shoulder Pain Rehabilitation Outcomes in Wheelchair Basketball Players? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

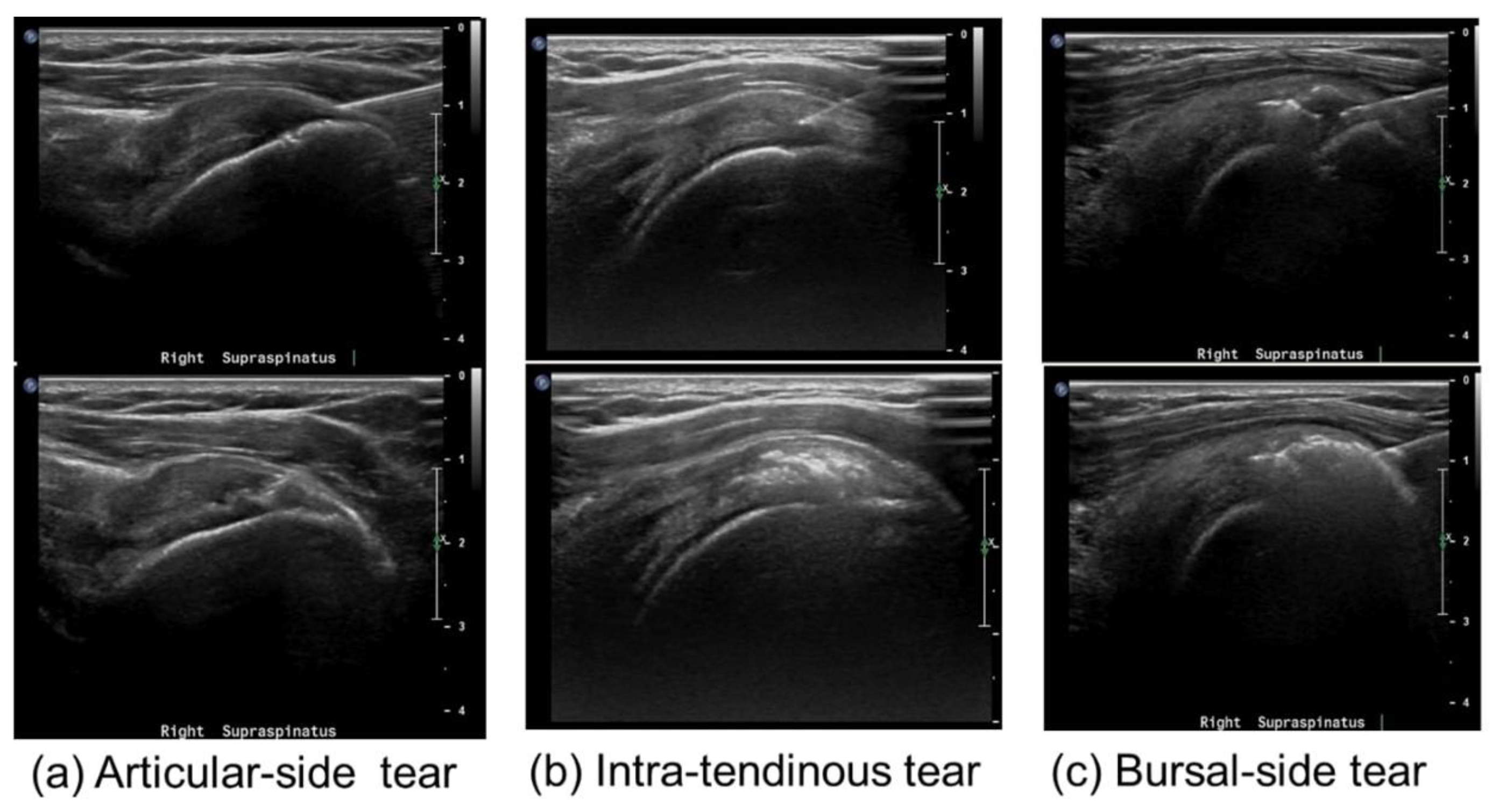

- Fukuda, H. Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: A modern view on Codman’s classic. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2000, 9, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.Y.; Khil, E.K.; Kim, T.S.; Kim, Y.W. Effect of co-administration of atelocollagen and hyaluronic acid on rotator cuff healing. Clin. Shoulder Elb. 2021, 24, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, V.; Özçakar, L. The Dodo Bird Is Not Extinct: Ultrasound Imaging for Supraspinatus Tendinosis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 98, e8–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, K.; Matsumoto, T. The joint side tear of the rotator cuff. A followup study by arthrography. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1994, 304, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.B.; Kim, E.Y.; Lim, K.P.; Heo, K.S. Does the Use of Injectable Atelocollagen during Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair Improve Clinical and Structural Outcomes? Clin. Shoulder Elb. 2019, 22, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, V.; Özçakar, L. Looking into the joint when it is frozen: A report on dynamic shoulder ultrasound. J. Back. Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2019, 32, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jost, B.; Pfirrmann, C.W.; Gerber, C.; Switzerland, Z. Clinical outcome after structural failure of rotator cuff repairs. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2000, 82, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, V.; Chang, K.-V.; Güvener, O.; Mezian, K.; Kara, M.; Leblebicioğlu, G.; Stecco, C.; Pirri, C.; Ata, A.M.; Dughbaj, M.; et al. EURO-MUSCULUS/USPRM Dynamic Ultrasound Protocols for Shoulder. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 101, e29–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugaya, H.; Maeda, K.; Matsuki, K.; Moriishi, J. Repair integrity and functional outcome after arthroscopic double-row rotator cuff repair. A prospective outcome study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2007, 89, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Ji, H.M.; Jo, K.H.; Bin, S.W.; Gong, H.S. Prognostic factors affecting anatomic outcome of rotator cuff repair and correlation with functional outcome. Arthroscopy 2009, 25, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, V.; Mezian, K.; Chang, K.-V.; Özçakar, L. Clinical/Sonographic Assessment and Management of Calcific Tendinopathy of the Shoulder: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abtahi, A.M.; Granger, E.K.; Tashjian, R.Z. Factors affecting healing after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. World J. Orthop. 2015, 6, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazzam, M.; Sager, B.; Box, H.N.; Wallace, S.B. The effect of age on risk of retear after rotator cuff repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JSES Int. 2020, 4, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thankam, F.G.; Dilisio, M.F.; Gross, R.M.; Agrawal, D.K. Collagen I: A kingpin for rotator cuff tendon pathology. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2018, 10, 3291–3309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ryösä, A.; Laimi, K.; Äärimaa, V.; Lehtimäki, K.; Kukkonen, J.; Saltychev, M. Surgery or conservative treatment for rotator cuff tear: A meta-analysis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 1357–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrado, B.; Bonini, I.; Alessio Chirico, V.; Rosano, N.; Gisonni, P. Use of injectable collagen in partial-thickness tears of the supraspinatus tendon: A case report. Oxf. Med. Case Rep. 2020, 2020, omaa103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solarino, G.; Bortone, I.; Vicenti, G.; Bizzoca, D.; Coviello, M.; Maccagnano, G.; Moretti, B.; D’Angelo, F. Role of biomechanical assessment in rotator cuff tear repair: Arthroscopic vs mini-open approach. World J. Orthop. 2021, 12, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conaire, E.Ó.; Delaney, R.; Lädermann, A.; Schwank, A.; Struyf, F. Massive Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears: Which Patients Will Benefit from Physiotherapy Exercise Programs? A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Romero, J.G.; Jiménez-Rejano, J.J.; Ridao-Fernández, C.; Chamorro-Moriana, G. Exercise-Based Muscle Development Programmes and Their Effectiveness in the Functional Recovery of Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: A Systematic Review. Diagnostic 2021, 11, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, F.; Pederiva, D.; Tedeschi, R.; Spinnato, P.; Origlio, F.; Faldini, C.; Miceli, M.; Stella, S.M.; Galletti, S.; Cavallo, M.; et al. Adhesive capsulitis: The importance of early diagnosis and treatment. J. Ultrasound 2024, 27, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulos, E.; Plakoutsis, G.; Chronopoulos, E.; Maria, P. Effectiveness of Combined Program of Manual Therapy and Exercise Vs Exercise Only in Patients With Rotator Cuff-related Shoulder Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Health 2023, 15, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Castillo, M.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.; Luque-Teba, A.; Trinidad-Fernández, M. The role of progressive, therapeutic exercise in the management of upper limb tendinopathies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2022, 62, 102645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farì, G.; Megna, M.; Fiore, P.; Ranieri, M.; Marvulli, R.; Bonavolontà, V.; Bianchi, F.P.; Puntillo, F.; Varrassi, G.; Reis, V.M. Real-Time Muscle Activity and Joint Range of Motion Monitor to Improve Shoulder Pain Rehabilitation in Wheelchair Basketball Players: A Non-Randomized Clinical Study. Clin. Pract. 2022, 12, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeClercq, M.G.; Fiorentino, A.M.; Lengel, H.A.; Ruzbarsky, J.J.; Robinson, S.K.; Oberlohr, V.T.; Whitney, K.E.; Millett, P.J.; Huard, J. Systematic Review of Platelet-Rich Plasma for Rotator Cuff Repair: Are We Adhering to the Minimum Information for Studies Evaluating Biologics in Orthopaedics? Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2021, 9, 23259671211041971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannetti de Sanctis, E.; Franceschetti, E.; De Dona, F.; Palumbo, A.; Paciotti, M.; Franceschi, F. The Efficacy of Injections for Partial Rotator Cuff Tears: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prodromos, C.C.; Finkle, S.; Prodromos, A.; Chen, J.L.; Schwartz, A.; Wathen, L. Treatment of Rotator Cuff Tears with platelet rich plasma: A prospective study with 2 year follow-up. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermi, S.; Gnasso, R.; Belviso, I.; Iommazzo, I.; Vecchiato, M.; Marchini, A.; Corsini, A.; Vittadini, F.; Demeco, A.; De Luca, M.; et al. Stem cell therapy in sports medicine: Current applications, challenges and future perspectives. J. Basic. Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2023, 34, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, U.G.; Lalli, A.; Medina, G.; Maffulli, N. Conservative Management of Partial Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2023, 31, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, B.; Bonini, I.; Chirico, V.; Filippini, E.; Liguori, L.; Magliulo, G.; Mazzuoccolo, G.; Rosano, N.; Gisonni, P. Ultrasound-guided collagen injections in the treatment of supraspinatus tendinopathy: A case series pilot study. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.J.; Yeo, S.M.; Noh, S.J.; Ha, C.-W.; Lee, B.C.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, S.J. Effect of platelet-rich plasma on the degenerative rotator cuff tendinopathy according to the compositions. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2019, 14, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.A.; Cole, B.J.; Spatny, K.P.; Sundman, E.; Romeo, A.A.; Nicholson, G.P.; Wagner, B.; Fortier, L.A. Leukocyte-Reduced Platelet-Rich Plasma Normalizes Matrix Metabolism in Torn Human Rotator Cuff Tendons. Am. J. Sports Med. 2015, 43, 2898–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, A.; Eroglu, A. Comparison of ultrasound-guided platelet-rich plasma, prolotherapy, and corticosteroid injections in rotator cuff lesions. J. Back. Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2020, 33, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vascellari, A.; Demeco, A.; Vittadini, F.; Gnasso, R.; Tarantino, D.; Belviso, I.; Corsini, A.; Frizziero, A.; Buttinoni, L.; Marchini, A.; et al. Orthobiologics Injection Therapies in the Treatment of Muscle and Tendon Disorders in Athletes: Fact or Fake? Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2024, 14, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsui, Y.; Gotoh, M.; Nakama, K.; Yamada, T.; Higuchi, F.; Nagata, K. Hyaluronic acid inhibits mRNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines and cyclooxygenase-2/prostaglandin E(2) production via CD44 in interleukin-1-stimulated subacromial synovial fibroblasts from patients with rotator cuff disease. J. Orthop. Res. 2008, 26, 1032–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, H.; Gotoh, M.; Kanazawa, T.; Ohzono, H.; Nakamura, H.; Ohta, K.; Nakamura, K.; Fukuda, K.; Teramura, T.; Hashimoto, T.; et al. Hyaluronic Acid Accelerates Tendon-to-Bone Healing After Rotator Cuff Repair. Am. J. Sports Med. 2017, 45, 3322–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manferdini, C.; Guarino, V.; Zini, N.; Raucci, M.G.; Ferrari, A.; Grassi, F.; Gabusi, E.; Squarzoni, S.; Facchini, A.; Ambrosio, L.; et al. Mineralization behavior with mesenchymal stromal cells in a biomimetic hyaluronic acid-based scaffold. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 3986–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osti, L.; Berardocco, M.; di Giacomo, V.; Di Bernardo, G.; Oliva, F.; Berardi, A.C. Hyaluronic acid increases tendon derived cell viability and collagen type I expression in vitro: Comparative study of four different Hyaluronic acid preparations by molecular weight. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015, 16, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Brindisino, F.; Barassi, G.; Sparvieri, E.; DI Iorio, A.; de Sire, A.; Ruosi, C. Combined ultrasound guided peritendinous hyaluronic acid (500–730 Kda) injection with extracorporeal shock waves therapy vs. extracorporeal shock waves therapy-only in the treatment of shoulder pain due to rotator cuff tendinopathy. A randomized clinical trial. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2022, 62, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Di Iorio, A.; Brindisino, F.; Paolucci, T.; Moretti, A.; Iolascon, G. Effectiveness of combined extracorporeal shock-wave therapy and hyaluronic acid injections for patients with shoulder pain due to rotator cuff tendinopathy: A person-centered approach with a focus on gender differences to treatment response. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, D.-S.; Lee, J.-K.; Yoo, J.-C.; Woo, S.-H.; Kim, G.-R.; Kim, J.-W.; Choi, N.-Y.; Kim, Y.; Song, H.-S. Atelocollagen Enhances the Healing of Rotator Cuff Tendon in Rabbit Model. Am. J. Sports Med. 2017, 45, 2019–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.H.; Won, J.Y.; Yoo, J.C. Clinical outcome of ultrasound-guided atelocollagen injection for patients with partial rotator cuff tear in an outpatient clinic: A preliminary study. Clin. Shoulder Elb. 2020, 23, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buda, M.; Dlimi, S.; Parisi, M.; Benoni, A.; Bisinella, G.; Di Fabio, S. Subacromial injection of hydrolyzed collagen in the symptomatic treatment of rotator cuff tendinopathy: An observational multicentric prospective study on 71 patients. JSES Int. 2023, 7, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thankam, F.G.; Dilisio, M.F.; Agrawal, D.K. Immunobiological factors aggravating the fatty infiltration on tendons and muscles in rotator cuff lesions. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2016, 417, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thankam, F.G.; Evan, D.K.; Agrawal, D.K.; Dilisio, M.F. Collagen type III content of the long head of the biceps tendon as an indicator of glenohumeral arthritis. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2019, 454, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, A.K.; Yannas, I.V.; Bonfield, W. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of collagen. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2004, 71, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, I.; Mishra, D.; Das, T.; Maiti, S.; Maiti, T.K. Caprine (goat) collagen: A potential biomaterial for skin tissue engineering. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2012, 23, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, D.; Mottola, R.; Palermi, S.; Sirico, F.; Corrado, B.; Gnasso, R. Intra-Articular Collagen Injections for Osteoarthritis: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, L.; Natali, M.L.; Brunetti, C.; Sannino, A.; Gallo, N. An Update on the Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Collagen Injectables for Aesthetic and Regenerative Medicine Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randelli, F.; Menon, A.; Giai Via, A.; Mazzoleni, M.G.; Sciancalepore, F.; Brioschi, M.; Gagliano, N. Effect of a Collagen-Based Compound on Morpho-Functional Properties of Cultured Human Tenocytes. Cells 2018, 7, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinello, T.; Bronzini, I.; Volpin, A.; Vindigni, V.; Maccatrozzo, L.; Caporale, G.; Bassetto, F.; Patruno, M. Successful recellularization of human tendon scaffolds using adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells and collagen gel. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2014, 8, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Kim, W.-J.; Lee, H. Healing of partial tear of the supraspinatus tendon after atelocollagen injection confirmed by MRI. Medicine 2020, 99, e23498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, B.; Bonini, I.; Tarantino, D.; Sirico, F. Ultrasound-guided collagen injections for treatment of plantar fasciopathy in runners: A pilot study and case series. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2020, 15, S793–S805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canty, E.G.; Kadler, K.E. Procollagen trafficking, processing and fibrillogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 1341–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, R.O. Integrins: Bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 2002, 110, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massoud, E.I.E. Healing of subcutaneous tendons: Influence of the mechanical environment at the suture line on the healing process. World J. Orthop. 2013, 4, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, G.-I.; Ahn, J.-H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Choi, B.-S.; Lee, S.-W. A hyaluronate-atelocollagen/beta-tricalcium phosphate-hydroxyapatite biphasic scaffold for the repair of osteochondral defects: A porcine study. Tissue Eng. Part. A 2010, 16, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thon, S.G.; O’Malley, L.; O’Brien, M.J.; Savoie, F.H. Evaluation of Healing Rates and Safety With a Bioinductive Collagen Patch for Large and Massive Rotator Cuff Tears: 2-Year Safety and Clinical Outcomes. Am. J. Sports Med. 2019, 47, 1901–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkash, U.; Avisar, E.; Volk, I.; Slevin, O.; Shohat, N.; El Haj, M.; Dolev, E.; Ashraf, E.; Luria, S. First clinical experience with a new injectable recombinant human collagen scaffold combined with autologous platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of lateral epicondylar tendinopathy (tennis elbow). J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2019, 28, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, B.; Mazzuoccolo, G.; Liguori, L.; Chirico, V.A.; Costanzo, M.; Bonini, I.; Bove, G.; Curci, L. Treatment of Lateral Epicondylitis with Collagen Injections: A Pilot Study. Muscle Ligaments Tendons J. 2019, 09, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Choi, Y.S.; You, M.-W.; Kim, J.S.; Young, K.W. Sonoelastography in the Evaluation of Plantar Fasciitis Treatment: 3-Month Follow-Up After Collagen Injection. Ultrasound Q. 2016, 32, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksh, N.; Hannon, C.P.; Murawski, C.D.; Smyth, N.A.; Kennedy, J.G. Platelet-rich plasma in tendon models: A systematic review of basic science literature. Arthroscopy 2013, 29, 596–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic, D.; Rodeo, S.A. Biological augmentation of rotator cuff tendon repair. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008, 466, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Albornoz, P.M.; Aicale, R.; Forriol, F.; Maffulli, N. Cell Therapies in Tendon, Ligament, and Musculoskeletal System Repair. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2018, 26, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godek, P.; Szczepanowska-Wolowiec, B.; Golicki, D. Collagen and platelet-rich plasma in partial-thickness rotator cuff injuries. Friends or only indifferent neighbours? Randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padulo, J.; Oliva, F.; Frizziero, A.; Maffulli, N. Basic principles and recommendations in clinical and field science research: 2018 update. Muscle Ligaments Tendons J. 2018, 8, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padulo, J.; De Giorgio, A.; Oliva, F.; Frizziero, A.; Maffulli, N. I performed experiments and I have results. Wow, and now? Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2017, 7, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1-34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Aldhafian, O.R.; Choi, K.-H.; Cho, H.-S.; Alarishi, F.; Kim, Y.-S. Outcome of intraoperative injection of collagen in arthroscopic repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tear: A retrospective cohort study. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2023, 32, e429–e436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durieux, N.; Vandenput, S.; Pasleau, F. [OCEBM levels of evidence system]. Rev. Med. Liege 2013, 68, 644–649. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, D.-J.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, B.-K.; Kim, Y.-S. Atelocollagen Injection Improves Tendon Integrity in Partial-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears: A Prospective Comparative Study. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2020, 8, 2325967120904012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latini, L.; Porta, F.; Maccarrone, V.; Zompa, D.; Cipolletta, E.; Mirza, R.M.; Filippucci, E.; Vreju, F.A. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Ultrasound-Guided Injection with Low-Molecular-Weight Peptides from Hydrolyzed Collagen in Patients with Partial Supraspinatus Tendon Tears: A Pilot Study. Life 2024, 14, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, B.D.; Khan, K.M.; Maffulli, N.; Cook, J.L.; Wark, J.D. Studies of surgical outcome after patellar tendinopathy: Clinical significance of methodological deficiencies and guidelines for future studies. Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2000, 10, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancino, F.; Di Matteo, V.; Mocini, F.; Cacciola, G.; Malerba, G.; Perisano, C.; De Martino, I. Survivorship and clinical outcomes of proximal femoral replacement in non-neoplastic primary and revision total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawker, G.A.; Mian, S.; Kendzerska, T.; French, M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63 (Suppl. 11), S240–S252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchignoni, F.; Vercelli, S.; Giordano, A.; Sartorio, F.; Bravini, E.; Ferriero, G. Minimal clinically important difference of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand outcome measure (DASH) and its shortened version (QuickDASH). J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2014, 44, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malavolta, E.A.; Yamamoto, G.J.; Bussius, D.T.; Assunção, J.H.; Andrade-Silva, F.B.; Gracitelli, M.E.C.; Ferreira Neto, A.A. Establishing minimal clinically important difference for the UCLA and ASES scores after rotator cuff repair. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2022, 108, 102894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louwerens, J.K.G.; van den Bekerom, M.P.J.; van Royen, B.J.; Eygendaal, D.; van Noort, A.; Sierevelt, I.N. Quantifying the minimal and substantial clinical benefit of the Constant-Murley score and the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand score in patients with calcific tendinitis of the rotator cuff. JSES Int. 2020, 4, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashjian, R.Z.; Deloach, J.; Green, A.; Porucznik, C.A.; Powell, A.P. Minimal clinically important differences in ASES and simple shoulder test scores after nonoperative treatment of rotator cuff disease. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2010, 92, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.I.; Jain, N.B. Minimal Clinically Important Difference of Shoulder Outcome Measures and Diagnoses: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 98, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urwin, M.; Symmons, D.; Allison, T.; Brammah, T.; Busby, H.; Roxby, M.; Simmons, A.; Williams, G. Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: The comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1998, 57, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roquelaure, Y.; Ha, C.; Leclerc, A.; Touranchet, A.; Sauteron, M.; Melchior, M.; Imbernon, E.; Goldberg, M. Epidemiologic surveillance of upper-extremity musculoskeletal disorders in the working population. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 55, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-T.; Chiang, C.-F.; Wu, C.-H.; Huang, Y.-T.; Tu, Y.-K.; Wang, T.-G. Comparative Effectiveness of Injection Therapies in Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: A Systematic Review, Pairwise and Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 336–349.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, T. Comparison of three common shoulder injections for rotator cuff tears: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuelle, C.W.; Cook, C.R.; Stoker, A.M.; Cook, J.L.; Sherman, S.L. In Vivo Toxicity of Local Anesthetics and Corticosteroids on Supraspinatus Tenocyte Cell Viability and Metabolism. Iowa Orthop. J. 2018, 38, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khoury, M.; Tabben, M.; Rolón, A.U.; Levi, L.; Chamari, K.; D’Hooghe, P. Promising improvement of chronic lateral elbow tendinopathy by using adipose derived mesenchymal stromal cells: A pilot study. J. Exp. Orthop. 2021, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.Z.; Ficklscherer, A.; Gülecyüz, M.F.; Paulus, A.C.; Niethammer, T.R.; Jansson, V.; Müller, P.E. Cell Toxicity in Fibroblasts, Tenocytes, and Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells—A Comparison of Necrosis and Apoptosis-Inducing Ability in Ropivacaine, Bupivacaine, and Triamcinolone. Arthroscopy 2017, 33, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Name | Patient No. | Follow-Up | Groups | Collagen Used | Intervention | Scores at Baseline | Scores at Last Follow-Up | Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. (2019) [12] | 121 | VAS: 3 days, 1 and 2 weeks KSS: 3, 12, 24 months |

| 3 mL of 3% porcine type-I atelocollagen | Single injection at baseline (after arthroscopy) | Group I VAS: 5.3 ± 2.1 KSS: 63.0 ± 15.1 Group II VAS: 6.3 ± 1.7 KSS: 61.5 ± 15.2 | Group I VAS: 1.2 ± 1.0 KSS: 80.1 ± 9.4 Group II VAS: 3.2 ± 1.7 KSS:82.3 ± 11.2 |

|

| Kim et al. (2020) [79] | 94 | 3, 12, and 24 months |

| 0.5 or 1 mL of 3%, porcine type-I atelocollagen | Single injection at baseline | Group I VAS: 4.1 ASES: 61.9 CoS: 68.1 Group II VAS: 3.6 ASES: 63.5 CoS: 65.8 Group III VAS: 3.4 ASES: 62.9 CoS: 68.4 | Group I VAS: 2.1 ± 1.2 ASES: 82.5 ± 12.3 CoS: 89.0 ± 6.9 Group II VAS: 1.4 ± 1.1 ASES: 79.3 ± 8.3 CoS: 82.0 ± 10.1 Group III VAS: 3.3 ± 2.5 ASES: 65.5 ± 8.5 CoS: 62.5 ± 11.5 | not reported |

| Chae et al. (2020) [48] | 15 | 2 months | Collagen injections PTRCT | 1 mL atelocollagen + 1 mL of lidocaine | Single injection at baseline | ASES: 57.0 KSS: 64.6 CoS: 56.4 VAS: 4.2 SST: 6.6 FVAS: 6.3 | ASES: 60.4 KSS: 68.5 CoS: 58.9 VAS: 3.7 SST: 6.9 FVAS: 7.1 | Post-injection pain (57%, 8/15) |

| Corrado et al. (2020) [36] | 18 | 2 weeks, 1 and 3 months | Collagen injections RCTP | 2 mL, porcine type-I atelocollagen | 4 injections (one a week for 4 weeks in a row) | CoS: 53.11 ± 12.7 DASH: 37.72 ± 19 | CoS: 75 ± 12.9 DASH: 18.67 ± 13 | Not reported |

| Godek et al. (2022) [71] | 82 | 6 weeks, 3 and 6 months |

| 2 mL, porcine type-I atelocollagen | 3 injections (one a week for 3 weeks in a row) | Group I VAS: 74% QuickDASH: 37 NRS: 5 Group II VAS: 68% QuickDASH: 42 NRS: 5.5 Group III VAS: 71% QuickDASH: 41 NRS: 6 | Group I VAS: 82% QuickDASH: 15 NRS: 1.5 Group II VAS: 80% QuickDASH: 20 NRS: 2 Group III VAS. 86% QuickDASH: 20 NRS: 1.8 | No complications |

| Aldhafian et al. (2023) [77] | 129 | 3, 6, and 12 months for all groups Last follow-up (months):

|

| 1 mL atelocollagen | Single injection at baseline (after arthroscopy) | Group I VAS: 4 ASES: 58 CoS: 62 KSS: 61 Group II VAS: 4 ASES: 61 CoS: 68 KSS: 68 Group III VAS: 4 ASES: 62 CoS: 68 KSS: 68 | Group I VAS: 2 ASES: 80 CoS: 76 KSS: 75 Group II VAS: 3 ASES: 74 CoS: 79 KSS: 81 Group III VAS: 3 ASES: 76 CoS: 73 KSS: 73 | Re-tear rates after 12 months:

|

| Buda et al. (2023) [49] | 71 | 1 and 6 months | Collagen injections

| 4 mg/2 mL, bovine collagen, low molecular weight (<3 kDa) | 2 injections (one at baseline and one between 9 and 17 days after the first one) | Overall population VAS at rest: 4.25 ± 3.10 VAS during movement: 6.56 ± 1.47 VAS at night: 5.33 ± 2.98 CoS: 63.76 ± 12.50 SST: 54.14 ± 20.16 Group I VAS at rest: 6.35 ± 2.29 VAS during movement: 7.26 ± 4.09 VAS at night: 6.56 ± 4.48 CoS: 51.52 ± 59.17 SST: 30.43 ± 40.58 Group II VAS at rest: 4.28 ± 2.07 VAS during movement: 6.57 ± 3.96 VAS at night: 5.03 ± 3.04 CoS: 65.32 ± 74.10 SST: 56.79 ± 72.58 Group III VAS at rest: 1.90 ± 0.95 VAS during movement: 5.85 ± 4.30 VAS at night: 4.55 ± 2.75 CoS: 75.1 ± 81.85 SST: 77.49 ± 81.24 | Overall population VAS at rest: 0.39 ± 0.77 VAS during movement: 1.87 ± 1.85 VAS at night: 0.7 ± 1.32 CoS: 84.07 ± 11.47 SST: 87.15 ± 14.99 Group I VAS at rest: 0.86 ± 0.99 VAS during movement: 1.77 ± 1.87 VAS at night: 0.91 ± 1.27 CoS: 75.10 ± 10.06 SST: 77.27 ± 16.7 Group II VAS at rest: 0.18 ± 0.56 VAS during movement: 1.89 ± 1.82 VAS at night: 0.59 ± 1.15 CoS: 85.37 ± 10.24 SST: 90.74 ± 13.34 Group III VAS at rest: 0.15 ± 0.49 VAS during movement: 1.9 ± 1.97 VAS at night: 0.65 ± 1.63 CoS: 92.45 ± 7.19 SST: 94.18 ± 7.69 | No complications |

| Latini et al. (2024) [80] | 21 | 2 and 12 weeks | Collagen injections | 5 mg/1 mL of hydrolyzed bovine collagen | 2 injections, at baseline and at 2 weeks | VAS: 63 ± 20.5 SPADI: 80.6 ± 21.5 | VAS: 37 ± 23.3 SPADI: 50.3 ± 23.5 | 1 progression to FTRCT |

| Reference | Study Size | Follow-Up | N Procedures | Type of Study | Diagnostic Certainty | Description of Injection Technique | Rehabilitation and Compliance | Outcome Criteria | Outcome Assessment | Selection Process | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al., 2019 [12] | 10 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 68 |

| Kim et al., 2020 [79] | 7 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 75 |

| Chae et al., 2020 [48] | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 57 |

| Corrado et al., 2020 [36] | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 52 |

| Godek et al., 2022 [71] | 7 | 0 | 7 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 71 |

| Aldhafian et al., 2023 [77] | 10 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 54 |

| Buda et al., 2023 [49] | 7 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 76 |

| Latini et al., 2024 [80] | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 58 |

| Maximum Score Possible | 10 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 100 |

| Mean ± Standard Deviation | 5.1 ± 4.4 | 1.5 ± 2 | 8.8 ± 1.5 | 5.6 ± 6.2 | 5 ± 0 | 6.8 ± 2.6 | 4.3 ± 1.7 | 10 ± 0 | 11.5 ± 1.4 | 5 ± 0 | 63.8 ± 9.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aicale, R.; Savarese, E.; Mottola, R.; Corrado, B.; Sirico, F.; Pellegrino, R.; Donati, D.; Tedeschi, R.; Ruosi, L.; Tarantino, D. Collagen Injections for Rotator Cuff Diseases: A Systematic Review. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15020028

Aicale R, Savarese E, Mottola R, Corrado B, Sirico F, Pellegrino R, Donati D, Tedeschi R, Ruosi L, Tarantino D. Collagen Injections for Rotator Cuff Diseases: A Systematic Review. Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(2):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15020028

Chicago/Turabian StyleAicale, Rocco, Eugenio Savarese, Rosita Mottola, Bruno Corrado, Felice Sirico, Raffaello Pellegrino, Danilo Donati, Roberto Tedeschi, Luca Ruosi, and Domiziano Tarantino. 2025. "Collagen Injections for Rotator Cuff Diseases: A Systematic Review" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 2: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15020028

APA StyleAicale, R., Savarese, E., Mottola, R., Corrado, B., Sirico, F., Pellegrino, R., Donati, D., Tedeschi, R., Ruosi, L., & Tarantino, D. (2025). Collagen Injections for Rotator Cuff Diseases: A Systematic Review. Clinics and Practice, 15(2), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15020028