Gender-Pain Questionnaire: Internal Validation of a Scale for Assessing the Influence of Chronic Pain Experience on Gender Identity and Roles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Item Development

2.2. Item Scoring

2.3. Content and Face Validity

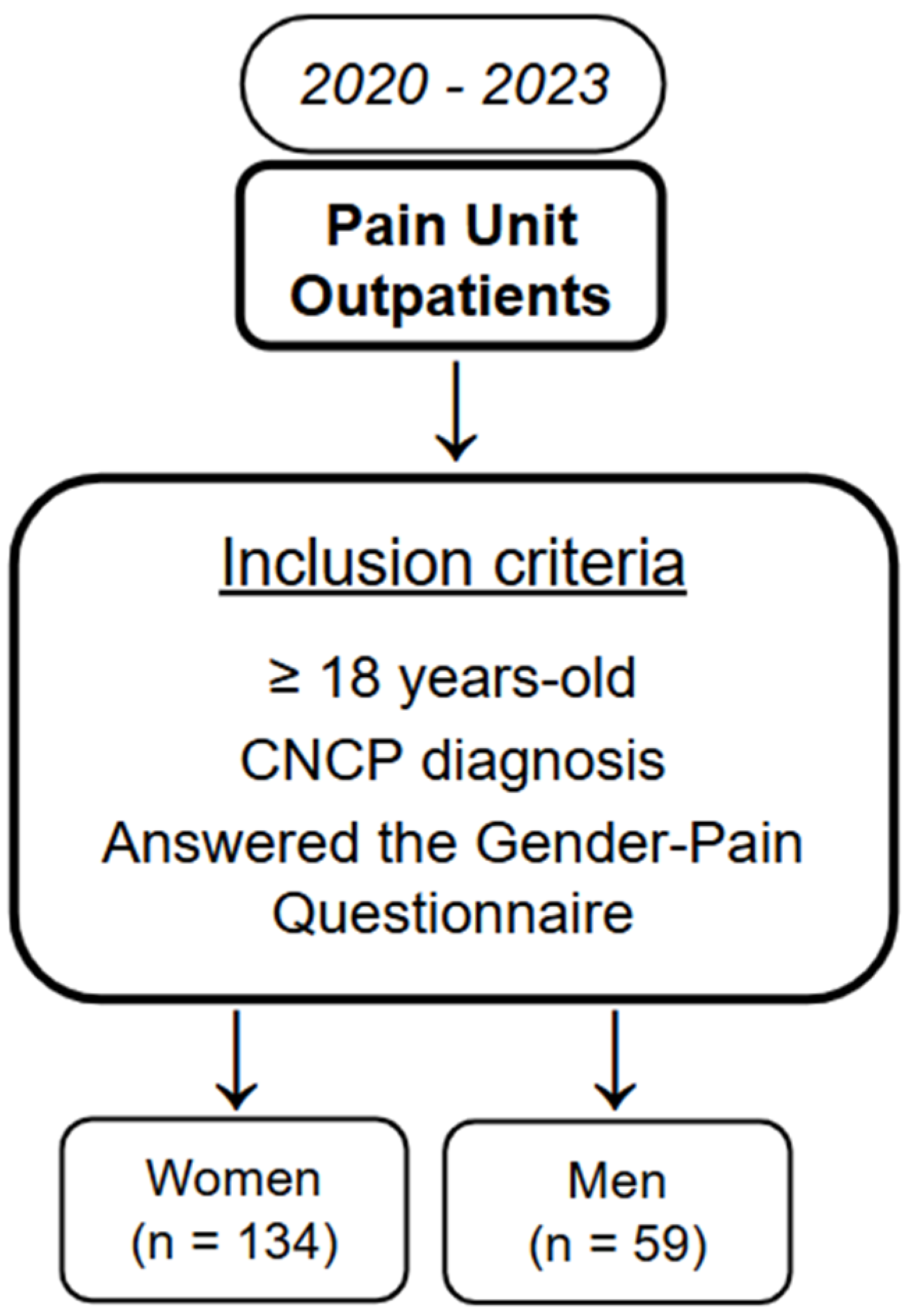

2.4. Internal Validity Study

2.4.1. Item Reduction

2.4.2. Internal Consistency

2.5. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Item Reduction

3.3. Internal Validity

4. Discussion

5. Future Perspectives/Next Steps

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CNCP | Chronic Non-Cancer Pain |

| COSMIN | COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement INstruments |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| PU | Pain Unit |

References

- Institute of Medicine. Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter? Wizemann, T.M., Pardue, M.-L., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, S.L.; Schiebinger, L.; Stefanick, M.L.; Cahill, L.; Danska, J.; de Vries, G.J.; Kibbe, M.R.; McCarthy, M.M.; Mogil, J.S.; Woodruff, T.K.; et al. Opinion: Sex inclusion in basic research drives discovery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5257–5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research. How to Integrate Sex and Gender INTO Research—CIHR. 2019. Available online: https://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50836.html (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Commission European. Fact Sheet: Gender Equality in Horizon 2020. 12 December 2013. Available online: https://genderedinnovations.stanford.edu/FactSheet_Gender_091213_final_2.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- National Institutes of Health. NOT-OD-15-102: Consideration of Sex as a Biological Variable in NIH-Funded Research. 12 December 2024. Available online: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-15-102.html (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Madsen, T.E.; Bourjeily, G.; Hasnain, M.; Jenkins, M.; Morrison, M.F.; Sandberg, K.; Tong, I.L.; Trott, J.; Werbinski, J.L.; McGregor, A.J. Sex- and Gender-Based Medicine: The Need for Precise Terminology. Gend. Genome 2017, 1, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athenstaedt, U. On the Content and Structure of the Gender Role Self-Concept: Including Gender-Stereotypical Behaviors in Addition to Traits. Psychol. Women Q. 2003, 27, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S. Are human rights capable of liberation? The case of sex and gender diversity. Aust. J. Hum. Rights 2009, 15, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibubos, A.N.; Otten, D.; Beutel, M.E.; Brähler, E. Validation of the Personal Attributes Questionnaire-8: Gender Expression and Mental Distress in the German Population in 2006 and 2018. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1604510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.L.; Greaves, L.; Repta, R. Better science with sex and gender: Facilitating the use of a sex and gender-based analysis in health research. Int. J. Equity Health 2009, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.W.; Stefanick, M.L.; Peragine, D.; Neilands, T.B.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Pilote, L.; Prochaska, J.J.; Cullen, M.R.; Einstein, G.; Klinge, I.; et al. Gender-related variables for health research. Biol. Sex Differ. 2021, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risman, B.J.; Froyum, C.M.; Scarborough, W.J. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. In Handbook of the Sociology of Gender; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bem, S.L. The measurement of psychological androgyny. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1974, 42, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, C. Gender Planning and Development: Theory, Practice and Training, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toner, P.; Hardy, E.; Mistral, W. A specialized maternity drug service: Examples of good practice. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2008, 15, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, G.J.; Schwegler, A.F.; Theodore, B.R.; Fuchs, P.N. Role of gender norms and group identification on hypothetical and experimental pain tolerance. Pain 2007, 129, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kersting, C.; Just, J.; Piotrowski, A.; Schmidt, A.; Kufeld, N.; Bisplinghoff, R.; Maas, M.; Bencheva, V.; Preuß, J.; Wiese, B.; et al. Development and feasibility of a sex- and gender-sensitive primary care intervention for patients with chronic non-cancer pain receiving long-term opioid therapy (GESCO): A study protocol. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2024, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samulowitz, A.; Gremyr, I.; Eriksson, E.; Hensing, G. “Brave Men” and “Emotional Women”: A Theory-Guided Literature Review on Gender Bias in Health Care and Gendered Norms towards Patients with Chronic Pain. Pain Res. Manag. 2018, 2018, 6358624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkle, K.L.; Decker, M.R. Gender-based violence and HIV: Reviewing the evidence for links and causal pathways in the general population and high-risk groups. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2013, 69 (Suppl. S1), 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañavate, G.; Meneghel, I.; Salanova, M. The Influence of Psychosocial Factors according to Gender and Age in Hospital Care Workers. Span. J. Psychol. 2023, 26, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, M.R.; Sofuoglu, M.; Petrakis, I.L.; Stefanovics, E.; Rosenheck, R.A. Sex Differences in Opioid Use Disorder Prevalence and Multimorbidity Nationally in the Veterans Health Administration. J. Dual Diagn. 2021, 17, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardes, S.F.; Lima, M.L. A contextual approach on sex-related biases in pain judgements: The moderator effects of evidence of pathology and patients’ distress cues on nurses’ judgements of chronic low-back pain. Psychol Health 2011, 26, 1642–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, S.F.; Lima, M.L. Being less of a man or less of a woman: Perceptions of chronic pain patients’ gender identities. Eur. J. Pain 2010, 14, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samulowitz, A.; Haukenes, I.; Grimby-Ekman, A.; Bergman, S.; Hensing, G.; Ghasemi, H. Psychosocial resources predict frequent pain differently for men and women: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandner, L.D.; Scipio, C.D.; Hirsh, A.T.; Torres, C.A.; Robinson, M.E. The perception of pain in others: How gender, race, and age influence pain expectations. J. Pain 2012, 13, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, E.E. Story and evidence about pain and gender. “The Princess on the Pea”—A myth about femininity penetrating to sciences? Lakartidningen 2004, 101, 3774, 3776, 3778–3779. [Google Scholar]

- Côté, D.; Coutu, M.F. A critical review of gender issues in understanding prolonged disability related to musculoskeletal pain: How are they relevant to rehabilitation? Disabil. Rehabil. 2010, 32, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Stratford, P.W.; Knol, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An international Delphi study. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, M.B.; Macey, T.A.; Nicolaidis, C.; Dobscha, S.K.; Duckart, J.P.; Morasco, B.J. Sex differences in the medical care of VA patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Pain Med. 2013, 14, 1839–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Vallerand, A.H.; Polomano, R.C. The relationship of gender to pain. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2000, 1 (Suppl. S1), 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prego-Domínguez, J.; Skillgate, E.; Orsini, N.; Takkouche, B. Social factors and chronic pain: The modifying effect of sex in the Stockholm Public Health Cohort Study. Rheumatology 2022, 61, 1802–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, A.; Montgomery, W.; Kahle-Wrobleski, K.; Nakamura, T.; Ueda, K. Impact of caring for persons with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia on caregivers’ health outcomes: Findings from a community based survey in Japan. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró, A.M.; Carracedo, P.; Agulló, L.; Bernardes, S.F.; Fernandes, L.d.M.M. Gendered dimension of chronic pain patients with low and middle income: A text mining analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauke, A.; Flintrop, J.; Brun, E.; Rugulies, R. The impact of work-related psychosocial stressors on the onset of musculoskeletal disorders in specific body regions: A review and meta-analysis of 54 longitudinal studies. Work. Stress 2011, 25, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen-Barr, E.; A Grooten, W.J.; Hallqvist, J.; Holm, L.W.; Skillgate, E. Are job strain and sleep disturbances prognostic factors for neck/shoulder/arm pain? A cohort study of a general population of working age in Sweden. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen-Barr, E.; Grooten, W.; Hallqvist, J.; Holm, L.; Skillgate, E. Are job strain and sleep disturbances prognostic factors for low-back pain?A cohort study of a general population of working age in Sweden. J. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 49, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; Loggia, M.L.; Polli, A.; Moens, M.; Huysmans, E.; Goudman, L.; Meeus, M.; Vanderweeën, L.; Ickmans, K.; Clauw, D. Sleep disturbances and severe stress as glial activators: Key targets for treating central sensitization in chronic pain patients? Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2017, 21, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escorial, M.; Muriel, J.; Agulló, L.; Zandonai, T.; Margarit, C.; Morales, D.; Peiró, A.M. Clinical prediction of opioid use disorder in chronic pain patients: A cohort-retrospective study with a pharmacogenetic approach. Minerva Anestesiol. 2024, 90, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agulló, L.; Muriel, J.; Margarit, C.; Escorial, M.; Garcia, D.; Herrero, M.J.; Hervás, D.; Sandoval, J.; Peiró, A.M. Sex Differences in Opioid Response Linked to OPRM1 and COMT genes DNA Methylation/Genotypes Changes in Patients with Chronic Pain. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloisi, A.M.; Bachiocco, V.; Costantino, A.; Stefani, R.; Ceccarelli, I.; Bertaccini, A.; Meriggiola, M.C. Cross-sex hormone administration changes pain in transsexual women and men. Pain 2007, 132 (Suppl. S1), S60–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawes, J.M.; Bennett, D.L. Addressing the gender pain gap. Neuron 2021, 109, 2641–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.K.H. Standards and Guidelines for Validation Practices: Development and Evaluation of Measurement Instruments. In Validity and Validation in Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences; Zumbo, B.D., Chan, E.K.H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Cantero, M.T.; Blasco-Blasco, M. Gender perspective in clinical epidemiology. Learning from spondyloarthritis. Gac. Sanit. 2020, 34, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovaní, V.; Blasco-Blasco, M.; Ruiz-Cantero, M.T.; Pascual, E. Understanding How the Diagnostic Delay of Spondyloarthritis Differs Between Women and Men: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. J. Rheumatol. 2017, 44, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Blasco, M.; Ruiz-Cantero, M.T.; Cairo, L.A.J.-H.Y.; Jovaní, V.; Pascual, E. Sex and Gender Interactions in the Lives of Patients with Spondyloarthritis in Spain: A Quantitative-qualitative Study. J. Rheumatol. 2017, 44, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.; Binder, A.; Wasner, G. Neuropathic Pain: Diagnosis, Pathophysiological Mechanisms, and Treatment. Lancet. Neurol. 2010, 9, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grünenthal, F. Barómetro del dolor crónico en la Comunidad Valenciana. Análisis de situación del impacto del dolor crónico en la Comunidad Valenciana. Canal Estrategia Editorial SL. 2024. Available online: https://www.fundaciongrunenthal.es/fundacion/pdfs/barometro-dolor-comunidad-valenciana.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Hyde, J.S.; Bigler, R.S.; Joel, D.; Tate, C.C.; van Anders, S.M. The future of sex and gender in psychology: Five challenges to the gender binary. Am. Psychol. 2019, 74, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Science Is Better with Sex and Gender: Strategic Plan 2018–2023. 12 December 2020. Available online: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/igh_strategic_plan_2018-2023-e.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

| Total (n = 193) | Women (n = 134) | Men (n = 59) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Med [IQR]) | 60 [51–73] | 65 [52–75] | 56 [49–66] | |

| Employment status (%) | ||||

| Active | 34 (18) | 23 (17) | 11 (18) | 0.006 |

| Unemployed | 12 (6) | 8 (6) | 4 (7) | |

| Retired | 60 (31) | 40 (30) | 20 (34) | |

| Homemaker | 27 (14) | 27 (20) | 0 **** | |

| Disability | 50 (26) | 30 (22) | 20 (34) | |

| NA | 10 (5) | 6 (5) | 4 (7) | - |

| Diagnostic delay (%) | ||||

| 3–12 months | 45 (23) | 29 (21) | 16 (27) | 0.524 |

| 12–24 months | 34 (18) | 21 (16) | 13 (22) | |

| 24 months−5 years | 33 (17) | 24 (18) | 9 (15) | |

| More than 5 years | 80 (41) | 59 (44) | 21 (36) | |

| NA | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | - |

| 1. Has your pain changed the way you are? Yes/No. How? |

| 2. Has the pain affected your self-esteem as a woman/man? Yes/No. How? |

| 3. Has the pain changed your image of yourself as a man/woman? Yes/No. How? |

| 4. Has the pain changed your masculinity or femininity? Yes/No. How? |

| 5. Has the pain generated a conflict between what you want/can (do) and what you think your family environment asks of you as a woman/man? Yes/No. How? |

| 6. Has the pain generated a conflict between what you want/can (do) and what the social environment asks of you as a woman/man? Yes/No. How? |

| 7. Has the pain affected your work tasks and/or responsibilities within your work environment? Yes/No. How? |

| 8. Did you do household chores before the diagnosis of the disease? Yes/No. |

| 9. Has the pain affected your tasks and/or domestic responsibilities? Yes/No. How? |

| 10. Has the pain affected your life project or your future plans? Yes/No. How? |

| 11. Has the pain affected your relationships? Yes/No. How? |

| 12. Has the pain affected your sexual relationships? Yes/No. How? |

| 13. Has the pain affected your family relationships? Yes/No. How? |

| 14. Do you think that your social, work or family position has worsened due to the pain? Yes/No. How? |

| 15. Do you think that the experience of pain would have been different instead of a man being a woman (or vice versa)? Yes/No. How? |

| Identity |

| 1. Has your pain changed the way you are? Yes/No. How? |

| 2. Has the pain affected your self-esteem as a woman/man? Yes/No. How? |

| 3. Has the pain changed your image of yourself as a man/woman? Yes/No. How? |

| 4. Has the pain changed your masculinity or femininity? Yes/No. How? |

| Relationships |

| 5. Has the pain affected your relationships? Yes/No. How? |

| 6. Has the pain affected your sexual relationships? Yes/No. How? |

| 7. Has the pain affected your family relationships? Yes/No. How? |

| Work |

| 8. Has the pain affected your work tasks and/or responsibilities within your work environment? Yes/No. How? |

| 9. Has the pain affected your life project or your future plans? Yes/No. How? |

| 10. Do you think that your social, work or family position has worsened due to the pain? Yes/No. How? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peiró, A.M.; Serrano-Gadea, N.; García-Torres, D.; Ruiz-Cantero, M.T.; Pérez-Jover, V. Gender-Pain Questionnaire: Internal Validation of a Scale for Assessing the Influence of Chronic Pain Experience on Gender Identity and Roles. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15100176

Peiró AM, Serrano-Gadea N, García-Torres D, Ruiz-Cantero MT, Pérez-Jover V. Gender-Pain Questionnaire: Internal Validation of a Scale for Assessing the Influence of Chronic Pain Experience on Gender Identity and Roles. Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(10):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15100176

Chicago/Turabian StylePeiró, Ana M., Noelia Serrano-Gadea, Daniel García-Torres, María Teresa Ruiz-Cantero, and Virtudes Pérez-Jover. 2025. "Gender-Pain Questionnaire: Internal Validation of a Scale for Assessing the Influence of Chronic Pain Experience on Gender Identity and Roles" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 10: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15100176

APA StylePeiró, A. M., Serrano-Gadea, N., García-Torres, D., Ruiz-Cantero, M. T., & Pérez-Jover, V. (2025). Gender-Pain Questionnaire: Internal Validation of a Scale for Assessing the Influence of Chronic Pain Experience on Gender Identity and Roles. Clinics and Practice, 15(10), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15100176