A Newborn with Cleft Palate Associated with PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Year | 2024 | 2024 | 2020 | 2019 | 2019 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2015 | 2015 | ∑ | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| author | Bregvadze [10] | Martín-Valbuena [11] | Martin [5] | Ciaccio [12] | Plamper [13] | Yotsumoto [14] | Kato [15] | Hansen-Kiss [16] | Busa [17] | Smpokou [18] | cases | percentage | present case |

| cases | 1 | 11 | 13 | 16 | 23 | 1 | 6 | 47 | 7 | 34 | 159 | ||

| male | 1 | 7 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 1 | 2 | 29 | 3 | 23 | 108 out of 159 | 68% | male |

| skin observations * | 1 out of 1 | 3 out of 10 | 13 out of 13 | 7 out of 16 | 17 out of 23 | 1 out of 1 | 1 out of 6 | 30 from 47 | 4 out of 7 | 12 out of 31 | 89 out of 155 | 57% | nuchal naevus flammeus |

| macrocephaly | 1 out of 1 | 7 out of 11 | 13 out of 13 | 16 out of 16 | 23 out of 23 | 1 out of 1 | 6 out of 6 | 46 from 47 | 6 out of 7 | 27 out of 27 | 146 out of 152 | 96% | yes |

| cardic/vascular | 0 out of 11 | 3 out of 16 | 1 out of 23 | 1 from 47 | 1 out of 7 | 16 out of 34 | 22 out of 138 | 16% | persistent ductus arteriosus | ||||

| developmental delay | 1 out of 1 | 8 out of 11 | 9 out of 13 | 9 out of 16 | 10 out of 23 | 1 out of 1 | 6 out of 6 | 15 from 33 | 4 out of 7 | 23 out of 25 | 86 out of 136 | 63% | motor |

| malignancy observed ** | 0 out of 11 | 1 out of 13 | 0 out of 16 | 2 out of 7 | 0 out of 47 | 5 out of 34 | 8 out of 128 | 6% | no | ||||

| thyroid abnormalities *** | 1 out of 1 | 1 out of 11 | 4 out of 13 | 1 out of 16 | 14 out of 23 | 7 out of 27 | 10 out of 18 | 38 out of 109 | 35% | no | |||

| autism spectrum disorder | 1 out of 1 | 3 out of 11 | 4 out of 16 | 1 out of 23 | 1 out of 1 | 1 out of 6 | 25 out of 33 | 1 out of 7 | 7 out of 7 | 44 out of 105 | 42% | n.a | |

| genital lentiginosis | 1 out of 1 | 0 out of 11 | 6 out of 6 | 0 out of 14 | 8 out of 15 | 12 out of 29 | 0 out of 3 | 19 out of 19 | 46 out of 98 | 47% | no | ||

| facial dysmorphism | 5 out of 11 | 14 out of 14 | 1 out of 1 | 6 out of 6 | 1 out of 47 | 27 out of 79 | 34% | no | |||||

| gastrointestinal polyposis | 1 out of 1 | 3 out of 3 | 6 out of 10 | 9 out of 12 | 19 out of 26 | 73% | n.a. | ||||||

| overgrowth | 1 out of 1 | 3 out of 11 | 3 out of 7 | 7 out of 19 | 37% | no | |||||||

| oral mucosal papillomatosis | 4 out of 13 | 4 out of 13 | 31% | no | |||||||||

| oral dysmorphism | 3 out of 11 | 3 out of 11 | 27% | cleft palate | |||||||||

| MRI white matter hyperdensity | 1 out of 7 | 4 out of 16 | 7 out of 15 | 0 out of 1 | 2 out of 6 | 5 out of 16 | 3 out of 5 | 22 out of 66 | 33% | yes | |||

| MRI cerebellar signs | 2 out of 7 | 6 out of 16 | 1 out of 15 | 0 out of 1 | 0 out of 16 | 9 out of 55 | 16% | no | |||||

| MRI enlarged perivascular spaces | 2 out of 7 | 10 out of 16 | 3 out of 15 | 1 out of 1 | 1 out of 6 | 3 out of 5 | 20 out of 50 | 40% | yes |

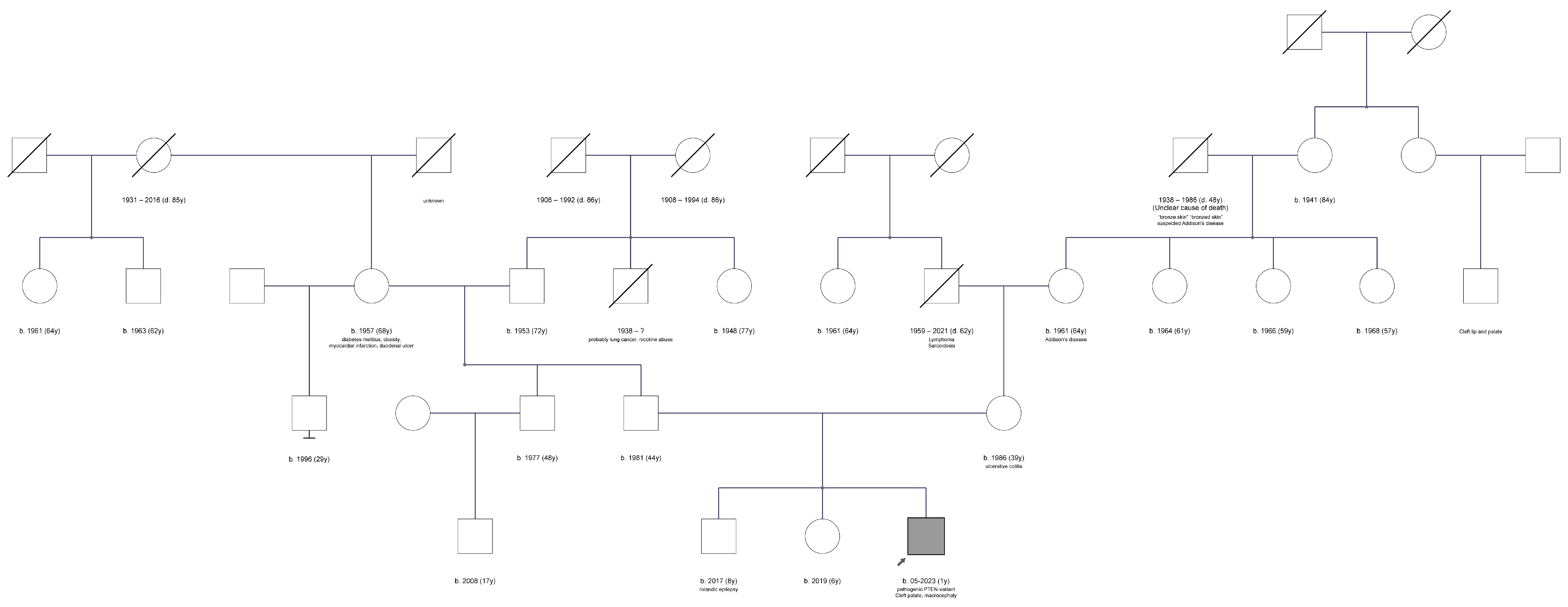

2. Case Description

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leibowitz, M.S.; Zelley, K.; Adams, D.; Brodeur, G.M.; Fox, E.; Li, M.M.; Mattei, P.; Pogoriler, J.; MacFarland, S.P. Neuroblastoma and cutaneous angiosarcoma in a child with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macken, W.L.; Tischkowitz, M.; Lachlan, K.L. PTEN Hamartoma tumor syndrome in childhood: A review of the clinical literature. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin Med. Genet. 2019, 181, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Rios, C.; De Leon Benedetti, L.S.; Tierradentro-Garcia, L.O.; Kilicarslan, O.A.; Caro-Dominguez, P.; Otero, H.J. Imaging findings of children with PTEN-related hamartoma tumor syndrome: A 20-year multicentric pediatric cohort. Pediatr. Radiol. 2024, 54, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, K.M., II; Dennis, M. Cowden’s disease. A possible new symptom complex with multiple system involvement. Ann. Intern. Med. 1963, 58, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, H.; Bessis, D.; Bourrat, E.; Mazereeuw-Hautier, J.; Morice-Picard, F.; Balguerie, X.; Chiaverini, C. Cutaneous lipomas and macrocephaly as early signs of PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2020, 37, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, K.A.; Allen, V.M.; MacDonald, M.E.; Smith, K.; Dodds, L. A population-based evaluation of antenatal diagnosis of orofacial clefts. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2008, 45, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, N.L.; Dixon, M.J. Revisiting the embryogenesis of lip and palate development. Oral Dis. 2022, 28, 1306–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansal, I.; Sellers, W.R. The biology and clinical relevance of the PTEN tumor suppressor pathway. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 2954–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestler, U.; Gräfe, D.; Strehlow, V.; Jauss, R.-T.; Merkenschlager, A.; Schönfeld, A.; Wilhelmy, F. A Newborn with Cleft Palate Associated with PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome. Authorea 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregvadze, K.; Jabeen, S.; Rafi, S.M.; Tkemaladze, T. The complexity of phosphatase and tensin homolog hamartoma tumor syndrome: A case report. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2024, 12, 2050313X241245317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Valbuena, J.; Gestoso-Uzal, N.; Justel-Rodríguez, M.; Isidoro-García, M.; Marcos-Vadillo, E.; Lorenzo-Hernández, S.M.; Criado-Muriel, M.C.; Prieto-Matos, P. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: Clinical and genetic characterization in pediatric patients. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2024, 40, 1689–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaccio, C.; Saletti, V.; D’Arrigo, S.; Esposito, S.; Alfei, E.; Moroni, I.; Tonduti, D.; Chiapparini, L.; Pantaleoni, C.; Milani, D. Clinical spectrum of PTEN mutation in pediatric patients. A bicenter experience. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2019, 62, 103596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plamper, M.; Gohlke, B.; Schreiner, F.; Woelfle, J. Phenotype-Driven Diagnostic of PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome: Macrocephaly, But Neither Height nor Weight Development, Is the Important Trait in Children. Cancers 2019, 11, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yotsumoto, Y.; Harada, A.; Tsugawa, J.; Ikura, Y.; Utsunomiya, H.; Miyatake, S.; Matsumoto, N.; Kanemura, Y.; Hashimoto-Tamaoki, T. Infantile macrocephaly and multiple subcutaneous lipomas diagnosed with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: A case report. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 12, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Mizuno, S.; Inaba, M.; Fukumura, S.; Kurahashi, N.; Maruyama, K.; Ieda, D.; Ohashi, K.; Hori, I.; Negishi, Y.; et al. Distinctive facies, macrocephaly, and developmental delay are signs of a PTEN mutation in childhood. Brain Dev. 2018, 40, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen-Kiss, E.; Beinkampen, S.; Adler, B.; Frazier, T.; Prior, T.; Erdman, S.; Eng, C.; Herman, G. A retrospective chart review of the features of PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome in children. J. Med. Genet. 2017, 54, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busa, T.; Milh, M.; Degardin, N.; Girard, N.; Sigaudy, S.; Longy, M.; Olshchwang, S.; Sobol, H.; Chabrol, B.; Philip, N. Clinical presentation of PTEN mutations in childhood in the absence of family history of Cowden syndrome. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2015, 19, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smpokou, P.; Fox, V.L.; Tan, W.H. PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome: Early tumour development in children. Arch. Dis. Child 2015, 100, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plamper, M.; Gohlke, B.; Woelfle, J. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome in childhood and adolescence-a comprehensive review and presentation of the German pediatric guideline. Mol. Cell Pediatr. 2022, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plamper, M.; Born, M.; Gohlke, B.; Schreiner, F.; Schulte, S.; Splittstößer, V.; Woelfle, J. Cerebral MRI and Clinical Findings in Children with PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome: Can Cerebral MRI Scan Help to Establish an Earlier Diagnosis of PHTS in Children? Cells 2020, 9, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardal, Ø.; Nevland, K.; Johannessen, A.C.; Vetti, H.H. The PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: How oral clinicians may save lives. Clin. Adv. Periodontics. 2023, 13, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, L.; Ni, Y.; Sadler, T.; Frazier, T.W.; Eng, C. Distinct metabolic profiles associated with autism spectrum disorder versus cancer in individuals with germline PTEN mutations. NPJ Genom. Med. 2022, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nestler, U.; Gräfe, D.; Strehlow, V.; Jauss, R.-T.; Merkenschlager, A.; Schönfeld, A.; Wilhelmy, F. A Newborn with Cleft Palate Associated with PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15010022

Nestler U, Gräfe D, Strehlow V, Jauss R-T, Merkenschlager A, Schönfeld A, Wilhelmy F. A Newborn with Cleft Palate Associated with PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome. Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleNestler, Ulf, Daniel Gräfe, Vincent Strehlow, Robin-Tobias Jauss, Andreas Merkenschlager, Annika Schönfeld, and Florian Wilhelmy. 2025. "A Newborn with Cleft Palate Associated with PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15010022

APA StyleNestler, U., Gräfe, D., Strehlow, V., Jauss, R.-T., Merkenschlager, A., Schönfeld, A., & Wilhelmy, F. (2025). A Newborn with Cleft Palate Associated with PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome. Clinics and Practice, 15(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15010022