Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Parents Regarding Ophthalmological Screening of Preschool-Aged Children in Jazan, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To assess parental knowledge of the importance of eye screening for preschool children (3–5 years) in the Jazan region (Saudi Arabia);

- To determine parents’ attitudes toward having their children screened for eye diseases;

- To determine whether parents have taken their children for eye screening and the reasons behind this;

- To determine the socio-demographic factors that are relevant for parents to take their children to health centers for ophthalmological screening.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design Setting and Population

2.2. Sample Size and Design

2.3. Method of Data Collection, Study Tools, and Piloting

2.4. Operational Definitions and Study Variables

2.5. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Consideration

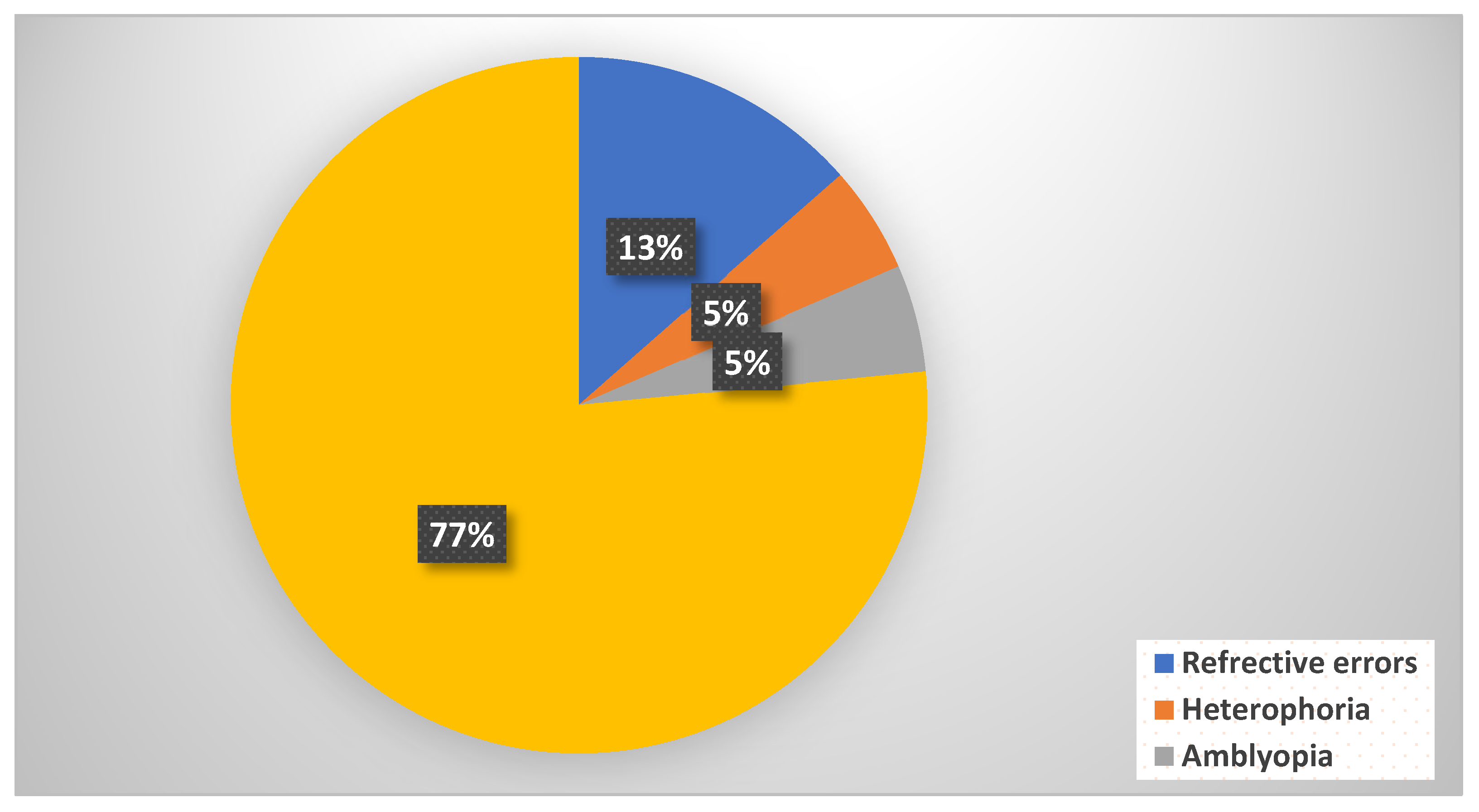

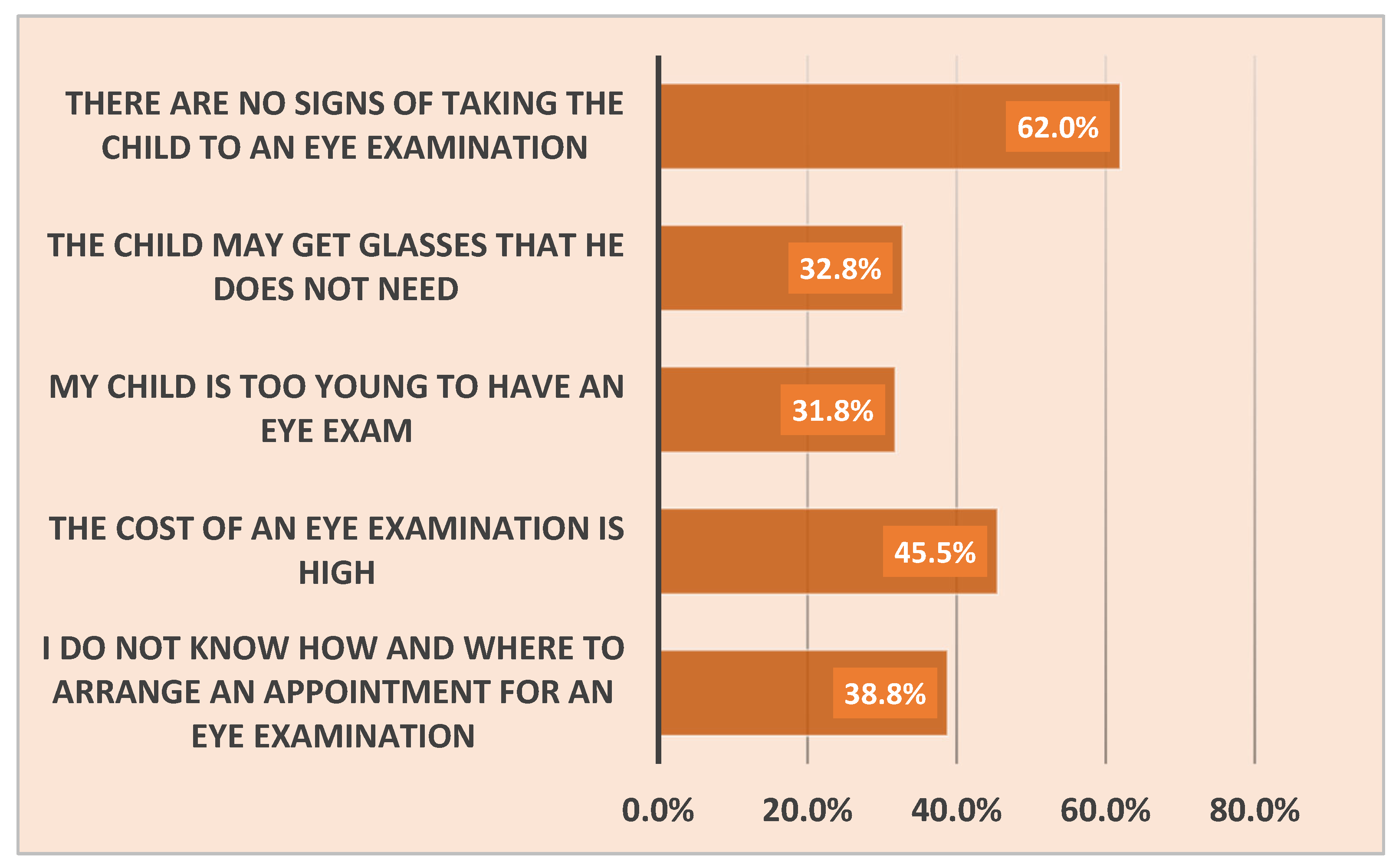

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th Revision. Current Version. Version for. 2003. Available online: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Al-Swailmi, F.K. Global prevalence and causes of visual impairment with special reference to the general population of Saudi Arabia. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jullien, S. Vision screening in newborns and early childhood. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21 (Suppl. 1), 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blindness and Visual Impairment. 2023. Available online: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- West, S.; Williams, C. Amblyopia in children (aged 7 years or less). BMJ Clin. Evid. 2016, 2016, 0709. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Donahue, S.P.; Baker, C.N. Procedures for the Evaluation of the Visual System by Pediatricians. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20153597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Grossman, D.C.; Curry, S.J.; Owens, D.K.; Barry, M.J.; Davidson, K.W.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W., Jr.; Kemper, A.R.; Krist, A.H.; et al. Vision Screening in Children Aged 6 Months to 5 Years: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2017, 318, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heijnsdijk, E.A.M.; Verkleij, M.L.; Carlton, J.; Horwood, A.M.; Fronius, M.; Kik, J.; Sloot, F.; Vladutiu, C.; Simonsz, H.J.; de Koning, H.J.; et al. The cost-effectiveness of different visual acuity screening strategies in three European countries: A microsimulation study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 28, 101868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakarchi, A.F.; Collins, M.E. Referral to community care from school-based eye care programs in the United States. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2019, 64, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, A.K.; Elflein, H.M.; Diefenbach, C.; Gräf, C.; König, J.; Schmidt, M.F.; Schnick-Vollmer, K.; Urschitz, M.S.; ikidS-Study Group. Recommendation for ophthalmic care in German preschool health examination and its adherence: Results of the prospective cohort study ikidS. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208164. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, L.; Subramanian, A.; Conway, M.L. Eye care in young children: A parent survey exploring access and barriers. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2018, 101, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basheikh, A.; Alhibshi, N.; Bamakrid, M.; Baqais, R.; Basendwah, M.; Howldar, S. Knowledge and attitudes regarding amblyopia among parents in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Res. Notes 2021, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaqr, A.M.; Masmali, A.M. The awareness of amblyopia among parents in Saudi Arabia. Ther. Adv. Ophthalmol. 2019, 11, 2515841419868103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrey, M.U. Parents’ awareness and perception of children’s eye diseases in Arar City. Ann. Clin. Anal. Med. 2019, 10, 746–751. [Google Scholar]

- Surrati, A.M.; Almuwarraee, S.M.; Mohammad, R.A.; Almatrafi, S.A.; Murshid, S.A.; Khayat, L.I.; Al-Habboubi, H.F. Parents’ Awareness and Perception of Children’s Eye Diseases in Madinah, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2022, 14, e22604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Mazrou, A.; Alsobaie, N.A.; Abdulrahman, A.K.B.; AlObaidan, O. Do Saudi parents have sufficient awareness of pediatric eye diseases in Riyadh? Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 34, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baashar, A.S.; Yaseen, A.A.M.B.; Halawani, M.A.; Alharbi, W.I.; Alhazmi, G.A.; Alam, S.S.; Tirkistani, M.F.; Eldin, E.E.M.N. Parents’ knowledge and practices about child eye health care in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Med. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 4, 454–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukati, V.N.; Moodley, V.R.; Mashige, K.P. Knowledge and practices of parents about child eye health care in the public sector in Swaziland. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2018, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaqr, A.M. Eye Care in Young Children: A Parents’ Perspective of Access and Barriers. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 2023, 18, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, A.; Paudel, P.; Massie, J.; Kong, N.; Kunthea, E.; Thomas, V.; Fricke, T.R.; Lee, L. Parents’ willingness to pay for children’s spectacles in Cambodia. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2021, 6, e000654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ross, E.L.; Stein, J.D. Enhancing the value of preschool vision screenings. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016, 134, 664–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akuffo, K.O.; Abdul-Kabir, M.; Agyei-Manu, E.; Tsiquaye, J.H.; Darko, C.K.; Addo, E.K. Assessment of availability, awareness and perception of stakeholders regarding preschool vision screening in kumasi, ghana: An exploratory study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | All Parents | Level of Knowledge | p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | ||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Gender | Male | 173 | (34.4) | 37 | (21.4) | 73 | (42.2) | 63 | (36.4) | 0.765 |

| Female | 330 | (65.6) | 71 | (21.5) | 129 | (39.1) | 130 | (39.4) | ||

| Age Groups | 18–24 years | 78 | (15.5) | 19 | (24.4) | 29 | (37.2) | 30 | (38.5) | 0.547 |

| 25–39 years | 217 | (43.1) | 45 | (20.7) | 80 | (36.9) | 92 | (42.4) | ||

| 40–54 years | 186 | (37.0) | 38 | (20.4) | 85 | (45.7) | 63 | (33.9) | ||

| 55 years or more | 22 | (4.4) | 6 | (27.3) | 8 | (36.4) | 8 | (36.4) | ||

| Educational Level | Postgraduate | 33 | (6.6) | 6 | (18.2) | 12 | (36.4) | 15 | (45.5) | 0.013 |

| University | 323 | (64.2) | 60 | (18.6) | 137 | (42.4) | 126 | (39.0) | ||

| High school | 89 | (17.7) | 19 | (21.3) | 37 | (41.6) | 33 | (37.1) | ||

| Intermediate | 19 | (3.8) | 6 | (31.6) | 4 | (21.1) | 9 | (47.4) | ||

| Primary | 39 | (7.8) | 15 | (51.7) | 9 | (31.0) | 5 | (17.2) | ||

| Occupation | Governmental sector | 241 | (47.9) | 52 | (21.6) | 104 | (43.2) | 85 | (35.3) | 0.617 |

| Private sector | 46 | (9.1) | 10 | (21.7) | 14 | (30.4) | 22 | (47.8) | ||

| Retired | 129 | (25.6) | 29 | (22.5) | 52 | (40.3) | 48 | (37.2) | ||

| Not working | 87 | (17.3) | 17 | (19.5) | 32 | (36.8) | 38 | (43.7) | ||

| Monthly Income | Less than 5000 | 131 | (26.0) | 31 | (23.7) | 49 | (37.4) | 51 | (38.9) | 0.790 |

| 5000 to 10,000 | 146 | (29.00 | 42 | (28.8) | 54 | (37.0) | 50 | (34.2) | ||

| 10,000–15,000 | 123 | (24.5) | 20 | (16.3) | 57 | (46.3) | 46 | (37.4) | ||

| 15,000 and more | 103 | (20.5) | 15 | (14.6) | 42 | (40.8) | 46 | (44.7) | ||

| Nationality | Saudi | 491 | (97.6) | 104 | (21.2) | 200 | (40.7) | 187 | (38.1) | 0.231 |

| Non-Saudi | 12 | (2.4) | 4 | (33.3) | 2 | (16.7) | 6 | (50.0) | ||

| Does your child have an eye problem | Yes | 112 | (22.3) | 28 | (25.0) | 50 | (44.6) | 34 | (30.4) | 0.138 |

| No | 391 | (77.7) | 80 | (20.5) | 152 | (38.9) | 159 | (40.7) | ||

| Parents’ Overall Level of Knowledge | 108 | (20.5) | 202 | (40.2) | 193 | (38.4) | ||||

| Items | All Parents | Gender | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers | Mothers | p-Value | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Can neglecting visual problems lead to permanent blindness in children? | Yes | 286 | (56.9) | 98 | (56.6) | 188 | (57.0) | 0.674 |

| No | 26 | (5.2) | 11 | (6.4) | 15 | (4.5) | ||

| I do not know | 191 | (38.0) | 64 | (37.0) | 127 | (38.5) | ||

| Does early treatment of lazy eyes lead to better results? | Yes | 430 | (85.5) | 140 | (80.9) | 290 | (87.9) | 0.109 |

| No | 9 | (1.8) | 4 | (2.3) | 5 | (1.5) | ||

| I do not know | 64 | (12.7) | 29 | (16.8) | 35 | (10.6) | ||

| Constant rubbing of the eye requires visiting an ophthalmologist. | Yes | 369 | (73.4) | 132 | (76.3) | 237 | (71.8) | 0.280 |

| No | 134 | (26.6) | 41 | (23.7) | 93 | (28.2) | ||

| Eye redness and tears require visiting an ophthalmologist. | Yes | 408 | (81.1) | 145 | (83.8) | 263 | (79.7) | 0.262 |

| No | 95 | (18.9) | 28 | (16.2) | 67 | (20.3) | ||

| If the child’s eyes do not move in unison in the same direction, a visit to the ophthalmologist is required. | Yes | 433 | (86.1) | 153 | (88.4) | 280 | (84.8) | 0.269 |

| No | 70 | (13.9) | 20 | (11.6) | 50 | (15.2) | ||

| Difficulty distinguishing distant/near shapes. | Yes | 446 | (88.7) | 153 | (88.4) | 293 | (88.8) | 0.907 |

| No | 57 | (11.3) | 20 | (11.6) | 37 | (11.2) | ||

| Definition of lazy eye. | Incorrect | 366 | (72.8) | 129 | (74.6) | 237 | (71.8) | 0.511 |

| Correct | 137 | (27.2) | 44 | (25.4) | 93 | (28.2) | ||

| Definition of strabismus. | Incorrect | 104 | (20.7) | 41 | (23.7) | 63 | (19.1) | 0.225 |

| Correct | 399 | (79.3) | 132 | (76.3) | 267 | (80.9) | ||

| Definition of refractive errors. | Incorrect | 72 | (14.3) | 29 | (16.8) | 43 | (13.0) | 0.256 |

| Correct | 431 | (85.7) | 144 | (83.2) | 287 | (87.0) | ||

| Statements | All Parents | Gender | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers | Mothers | p-Value | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Early eye examinations for children reduce the complications of visual problems. | Agree | 461 | (91.7) | 161 | (93.1) | 300 | (90.9) | 0.327 |

| Not sure | 33 | (6.6) | 11 | (6.4) | 22 | (6.7) | ||

| Disagree | 9 | (1.8) | 1 | (0.6) | 8 | (2.4) | ||

| The increased use of electronic devices by children requires the need for an early eye examination. | Agree | 456 | (90.7) | 158 | (91.3) | 298 | (90.3) | 0.781 |

| Not sure | 42 | (8.3) | 14 | (8.1) | 28 | (8.5) | ||

| Disagree | 5 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.6) | 4 | (1.2) | ||

| Will wearing glasses improve your child’s vision? | Agree | 262 | (52.1) | 79 | (45.7) | 183 | (55.5) | 0.107 |

| Not sure | 208 | (41.4) | 82 | (47.4) | 126 | (38.2) | ||

| Disagree | 33 | (6.6) | 12 | (6.9) | 21 | (6.4) | ||

| Academic performance is affected by visual problems. | Agree | 345 | (68.6) | 115 | (66.5) | 230 | (69.7) | 0.738 |

| Not sure | 107 | (21.3) | 40 | (23.1) | 67 | (20.3) | ||

| Disagree | 51 | (10.1) | 18 | (10.4) | 33 | (10.0) | ||

| Can early eye examinations of your child prevent or treat permanent damage from lazy eyes/blurriness and blurred vision? | Agree | 437 | (86.9) | 150 | (86.7) | 287 | (87.0) | 0.614 |

| Not sure | 60 | (11.9) | 22 | (12.7) | 38 | (11.5) | ||

| Disagree | 6 | (1.2) | 1 | (0.6) | 5 | (1.5) | ||

| Do you think that children (under the age of six) are more likely to have strabismus? | Agree | 244 | (48.5) | 83 | (48.0) | 161 | (48.8) | 0.854 |

| Not sure | 231 | (45.9) | 79 | (45.7) | 152 | (46.1) | ||

| Disagree | 28 | (5.6) | 11 | (6.4) | 17 | (5.2) | ||

| Do you think that early detection of myopia and farsightedness in children contributes to reducing complications? | Agree | 438 | (87.1) | 150 | (86.7) | 288 | (87.3) | 0.741 |

| Not sure | 60 | (11.9) | 22 | (12.7) | 38 | (11.5) | ||

| Disagree | 5 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.6) | 4 | (1.2) | ||

| Does your child sitting close to the TV make you take him for an early eye examination? | Agree | 397 | (78.9) | 136 | (78.6) | 261 | (79.1) | 0.511 |

| Not sure | 89 | (17.7) | 29 | (16.8) | 60 | (18.2) | ||

| Disagree | 17 | (3.4) | 8 | (4.6) | 9 | (2.7) | ||

| Does a genetic vision problem in the family increase the importance of early examination? | Agree | 427 | (84.9) | 145 | (83.8) | 282 | (85.5) | 0.887 |

| Not sure | 65 | (12.9) | 24 | (13.9) | 41 | (12.4) | ||

| Disagree | 11 | (2.2) | 4 | (2.3) | 7 | (2.1) | ||

| Does having an eye examination center nearby increase your demand for an early examination of your child? | Agree | 434 | (86.3) | 150 | (86.7) | 284 | (86.1) | 0.155 |

| Not sure | 59 | (11.7) | 17 | (9.8) | 42 | (12.7) | ||

| Disagree | 10 | (2.0) | 6 | (3.5) | 4 | (1.2) | ||

| Factors | All Parents | Gender | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers | Mothers | p-Value | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Has your child ever had any type of visual examination? | Yes | 208 | (41.4) | 86 | (49.7) | 122 | (37.0) | 0.006 |

| No | 295 | (58.6) | 87 | (50.3) | 208 | (63.0) | ||

| Age of child when first eye exam was performed? | Less than one year | 25 | (10.3) | 8 | (8.5) | 17 | (11.5) | 0.758 |

| One year to less than five | 113 | (46.7) | 45 | (47.9) | 68 | (45.9) | ||

| Five years and more | 104 | (43.0) | 41 | (43.6) | 63 | (42.6) | ||

| How many times has the child undergone a routine eye examination? | Every year | 42 | (16.1) | 19 | (19.0) | 23 | (14.3) | 0.196 |

| More than once a year | 54 | (20.7) | 20 | (20.0) | 34 | (21.1) | ||

| Every two years | 21 | (8.0) | 9 | (9.0) | 12 | (7.5) | ||

| Every five years | 6 | (2.3) | 5 | (5.0) | 1 | (0.6) | ||

| Only when the child reports a problem | 83 | (31.8) | 29 | (29.0) | 54 | (33.5) | ||

| Not sure | 55 | (21.1) | 18 | (18.0) | 37 | (23.0) | ||

| Reasons for conducting eye screening. | The child plays with toys from a close distance | 154 | (61.4) | 61 | (62.9) | 93 | (60.4) | 0.692 |

| The child rubs his eye frequently | 115 | (46.2) | 42 | (46.2) | 73 | (46.2) | 0.994 | |

| The child’s head tilts to one side frequently | 77 | (31.2) | 28 | (30.8) | 49 | (31.4) | 0.916 | |

| The child suffers from a squint in the eyes | 66 | (26.7) | 29 | (31.5) | 37 | (23.9) | 0.189 | |

| The child complains of double vision (one thing perceived as two) | 61 | (24.2) | 23 | (24.2) | 38 | (24.2) | 0.998 | |

| The child suffers from frequent tears and has red eyes | 117 | (45.7) | 44 | (45.8) | 73 | (45.6) | 0.974 | |

| Variable | Coef | SE Coef | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 70.72 | 2.57 | 27.48 | 0.000 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (ref) | 0.98 | 1.91 | 0.51 | 0.609 |

| Child with any eye problem | ||||

| No (ref) | −6.07 | 2.45 | −2.48 | 0.014 |

| Health center | ||||

| No (ref) | 2.30 | 2.03 | 1.13 | 0.257 |

| Conducted early screening | ||||

| No (ref) | 5.45 | 2.10 | 2.60 | 0.010 |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban (ref) | −0.18 | 1.87 | −0.09 | 0.925 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahfouz, M.S.; Mahmoud, S.S.; Haroobi, S.Q.; Bahkali, L.M.; Numan, S.I.; Taheri, A.M.; Hakami, O.A.; Zunquti, O.A.; Khered, S.M. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Parents Regarding Ophthalmological Screening of Preschool-Aged Children in Jazan, Saudi Arabia. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 2522-2532. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract14060198

Mahfouz MS, Mahmoud SS, Haroobi SQ, Bahkali LM, Numan SI, Taheri AM, Hakami OA, Zunquti OA, Khered SM. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Parents Regarding Ophthalmological Screening of Preschool-Aged Children in Jazan, Saudi Arabia. Clinics and Practice. 2024; 14(6):2522-2532. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract14060198

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahfouz, Mohamed Salih, Samy Shaban Mahmoud, Saleha Qaseem Haroobi, Latifah Mohammed Bahkali, Shahad Ibrahim Numan, Areen Mohsen Taheri, Ohoud Ali Hakami, Orjuwan Adel Zunquti, and Sarah Mohammed Khered. 2024. "Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Parents Regarding Ophthalmological Screening of Preschool-Aged Children in Jazan, Saudi Arabia" Clinics and Practice 14, no. 6: 2522-2532. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract14060198

APA StyleMahfouz, M. S., Mahmoud, S. S., Haroobi, S. Q., Bahkali, L. M., Numan, S. I., Taheri, A. M., Hakami, O. A., Zunquti, O. A., & Khered, S. M. (2024). Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Parents Regarding Ophthalmological Screening of Preschool-Aged Children in Jazan, Saudi Arabia. Clinics and Practice, 14(6), 2522-2532. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract14060198