“Sometimes It Felt Great, and Sometimes It Just Went Pear-Shaped”: Experiences and Perceptions of School Nurses’ Motivational Interviewing Competence: A Convergent Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

1.2. Study Aims

- How do objective ratings of school nurses’ MI quality correlate with the subjective quality ratings from school nurses and parents?

- What are school nurses’ and parents’ perceptions of delivering and participating in MI sessions?

- How do objective and subjective ratings of MI sessions resonate with school nurses’ and parents’ perceptions of the same MI sessions?

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Design

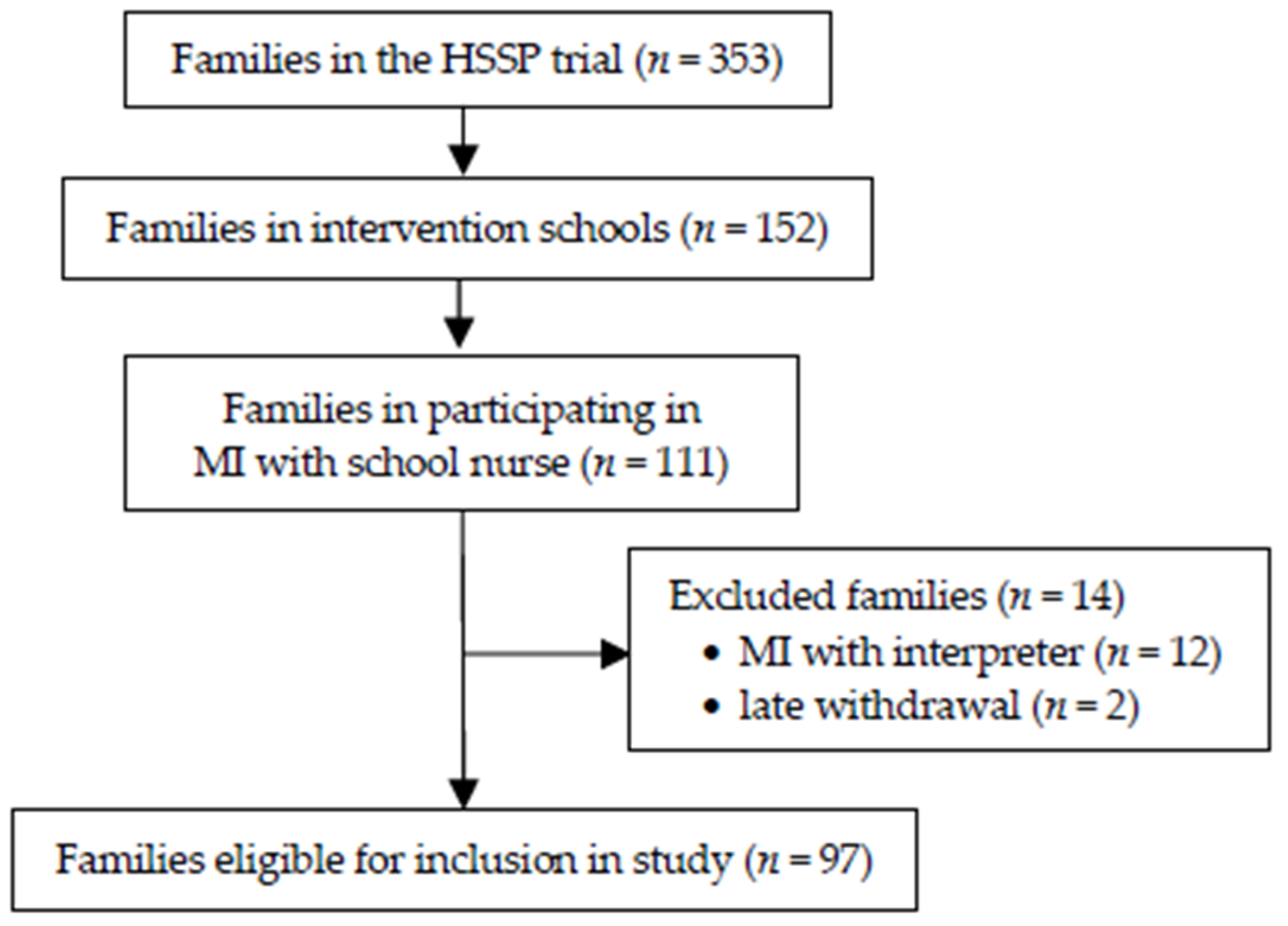

2.2. Participants

Motivational Interviewing Training

2.3. Ethical Approval

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Quantitative Data

MITI Ratings

School Nurses’ Ratings

Parents’ Ratings

2.4.2. Qualitative Data

Interviews with School Nurses

Interviews with Parents

2.5. Data Analyses

2.5.1. Statistical Analysis

2.5.2. Qualitative Analysis

2.5.3. Integrated Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Ratings and Correlations

3.3. Qualitative Findings

3.3.1. Meeting the Other

Shifting Power Relations in Sensitive Meetings

“There was no lecturing from me, no finger-wagging [Swe: pekpinnar] from the school nurse so to speak...the parents were involved in a different way than just me sitting and lecturing”.(School nurse 1)

“No, it’s much easier of course to talk about screen time or about eating candy every day or something like that, but the weight is very loaded... I think some parents feel guilty or they take it personally... that they are bad parents who let their child become, get obese, develop obesity”.(School nurse 1)

Respectful and Professional

“Yes, it went fantastically well. Yes, she was amazing, she gives information calmly and it was not stressful and on a good level. I remember this conversation, it was really-really great.”(Father 1)

“She [the school nurse] had some papers in front of her that she followed, but it felt... I do not know, stiff and strange”.(Mother 1)

Just Taking the Time to Listen and Confirm

“She [the mother] kind of threw herself and hugged me really hard. So, that’s a little bit what I mean, to be listened to. I think most parents experienced that during the conversation, that they actually got the chance and the time”.(School nurse 2)

“…then there was some [parents] in my opinion, who didn’t get much out of the visit. Because it was all about [the parent] figuring things out, and many peoplejustwant things served like, that you [the school nurse] should have a ready solution, like this is what you should do”.(School nurse 3)

Person-Centred—Or Not

“I thought she [the school nurse] felt very informed and yes, like not “pushy” in any way, but rather that I should come up with solutions and things like that. It wasn’t like a lecture. I had to think and reflect more myself. That’s what I thought was good... I was leading the conversation. It wasn’t like she [the school nurse] was in charge, but I kind of got to talk about what I was experiencing and if there was anything that I could change and improve on. Like that. I got some support, but that I had to think myself about what I could do to improve our situation as a family”.(Mother 2)

“No, it was more that it [the MI session] didn’t give anything new. It was more to state that ‘yes, she eats as she does, is alert and energetic and she eats what she wants.’ Yeah, I don’t know it was like, nothing concrete. (Interviewer: “How would you have liked it?”) Well, to get better advice on how to get her to eat a little differently”.(Mother 3)

3.3.2. Perceived Quality

Mastering MI as a Method

“Sometimes it felt great, and I experienced a good flow in the conversation, and sometimes it just felt like this just went pear-shaped [Swe: ‘skit och pannkaka’], there was no MI whatsoever. And that’s probably perfectly normal, but still…”(School nurse 4)

“I had a hard time finding this change talk, and I ended up in a more supportive role. So, I really had to work to remember, have mine, have a small paper with supporting notes in front of me and things like that... Not to miss the change talk”.(School nurse 5)

Motivated and Empowered

“It [the MI session] was like an eye-opener, even at the first meeting. You always had it somewhere subconscious, but it was only after this conversation with the school nurse, all these questions and these ideas about how to improve and what you could do. That’s when I got this commitment, and the motivation to deal with this [healthy behaviour change], so to speak.”(Father 2)

“Well...you got confirmation that you were on the right path, and you got to know things like... Even though you’re a parent, you don’t know everything and sometimes it’s nice to just be able to listen to others perspective. So, it was like a reassurance from her [the school nurse]”.(Mother 4)

Challenges and Lessons Learnt

“This MI was very difficult [with interpreter], I couldn’t do it. I know I tried at some point, but I then understood that the interpreter had, from the reaction of the parents, that they had got it wrong, so that I kind of had to give that [using MI with interpreter] up a little bit”.(School nurse 1)

“When you need to have these nuances in the conversation. Like, how does the interpreter affirm, how does the interpreter translate my reflections and affirmations, you know…”.(School nurse 6)

“There was one mother that really moved me. Because she thought she was a terrible mother, but she did so much, and she had tried so hard. And for me [the school nurse] just to be able to confirm and see her. She [the mother] was sitting here crying at the end, because she felt ‘No, I’m not such a bad mom after all’”.(School nurse 6)

3.4. Joint Display of Findings

3.4.1. Recognise and Cultivate Parents’ Motivation

3.4.2. Ability to Listen and Reflect what Parents Say

3.4.3. Show Consideration for Parents’ Worldview

4. Discussion

4.1. Recognise and Cultivate Motivation

4.2. Ability to Listen and Reflect

4.3. Show Consideration of Worldview

4.4. Implications and Future Research

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1659–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, A.S.; Mulder, C.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Van Mechelen, W.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: A systematic review of the literature. Obes. Rev. 2008, 9, 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craigie, A.M.; Lake, A.A.; Kelly, S.A.; Adamson, A.J.; Mathers, J.C. Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review. Maturitas 2011, 70, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, T.; Moore, T.; Hooper, L.; Gao, Y.; Zayegh, A.; Ijaz, S.; Elwenspoek, M.; Foxen, S.C.; Magee, L.; O’Malley, C.; et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 7, CD001871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Niermann, C.Y.N.; Gerards, S.M.P.L.; Kremers, S.P.J. Conceptualizing family influences on children’s energy balance-related behaviors: Levels of interacting family environmental subsystems (the LIFES framework). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wettergren, B.; Blennow, M.; Hjern, A.; Söder, O.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Child Health Systems in Sweden. J. Pediatr. 2016, 177, S187–S202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swedish Code of Statutes. The Swedish Education Act [Swe: Skollag] SFS 2010:800. 2011. Available online: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800 (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, Swedish National Agency for Education. Guidance for School Health Services; Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016.

- Håkansson Eklund, J.; Holmström, I.K.; Kumlin, T.; Kaminsky, E.; Skoglund, K.; Höglander, J.; Sundler, A.J.; Condén, E.; Meranius, M.S. “Same same or different?” A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stievano, A.; Tschudin, V. The ICN Code of Ethics for Nurses; International Council of Nurses: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Association of School Nurses; Swedish Society of Nursing. Description of Required Competences for School Nurses in School Health Care Services; Swedish Society of Nursing: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl, B.; Moleni, T.; Burke, B.L.; Butters, R.; Tollefson, D.; Butler, C.; Rollnick, S. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 93, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S.P. Motivational Interviewing Helping People Change, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers, T.B. The Relationship in Motivational Interviewing. Psychotherapy 2014, 51, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, S.P.; Sheng, E.; Imel, Z.E.; Baer, J.; Atkins, D.C. More than reflections: Empathy in motivational interviewing includes language style synchrony between therapist and client. Behav. Ther. 2015, 46, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, W.R.; Yahne, C.E.; Moyers, T.B.; Martinez, J.; Pirritano, M. A Randomized Trial of Methods to Help Clinicians Learn Motivational Interviewing. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 72, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Enö Persson, J.; Bohman, B.; Forsberg, L.; Beckman, M.; Tynelius, P.; Rasmussen, F.; Ghaderi, A. Proficiency in Motivational Interviewing among Nurses in Child Health Services Following Workshop and Supervision with Systematic Feedback. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Small, J.W.; Frey, A.; Lee, J.; Seeley, J.R.; Scott, T.M.; Sibley, M.H. Fidelity of Motivational Interviewing in School-Based Intervention and Research. Prev. Sci. 2020, 22, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, R.; Burnard, P. Research for Evidence-Based Practice in Healthcare, 2nd ed.; John and Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Perepletchikova, F.; Treat, T.A.; Kazdin, A.E. Treatment Integrity in Psychotherapy Research: Analysis of the Studies and Examination of the Associated Factors. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 75, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, I.; Oster, C.; Lawn, S. Assessing competence in health professionals’ use of motivational interviewing: A systematic review of training and supervision tools. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyers, T.B.; Rowell, L.N.; Manuel, J.K.; Ernst, D.; Houck, J.M. The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code (MITI 4): Rationale, Preliminary Reliability and Validity. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2016, 65, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moyers, T.B.; (University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA); Manuel, J.K.; (San Francisco V.A. Medical Center, San Francisco, CA, USA); Ernst, D.; (Denise Ernst Training and Consulting, Portland, OR, USA). Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Coding Manual 4.1. Unpublished manual, 2014.

- Martino, S.; Ball, S.; Nich, C.; Frankforter, T.L.; Carroll, K.M. Correspondence of motivational enhancement treatment integrity ratings among therapists, supervisors, and observers. Psychother. Res. 2009, 19, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, A.; Dauber, S.; Lichvar, E.; Bobek, M.; Henderson, C.E. Validity of Therapist Self-Report Ratings of Fidelity to Evidence-Based Practices for Adolescent Behavior Problems: Correspondence between Therapists and Observers. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2014, 42, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, S.A.; Latchford, G.; Tober, G. Client experiences of motivational interviewing: An interpersonal process recall study. Psychol. Psychother. 2016, 89, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Angus, L.E.; Kagan, F. Therapist empathy and client anxiety reduction in motivational interviewing: “She carries with me, the experience”. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 4, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, M.; Westra, H.; Angus, L.; Kertes, A. Client experiences of motivational interviewing for generalized anxiety disorder: A qualitative analysis. Psychother. Res. 2011, 21, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Elinder, L.S.; Patterson, E.; Nyberg, G.; Norman, A. A Healthy School Start Plus for prevention of childhood overweight and obesity in disadvantaged areas through parental support in the school setting—Study protocol for a parallel group cluster randomised trial (Report). BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saaristo, T.; Peltonen, M.; Lindström, J.; Saarikoski, L.; Sundvall, J.; Eriksson, J.G.; Tuomilehto, J. Cross-sectional evaluation of the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score: A tool to identify undetected type 2 diabetes, abnormal glucose tolerance and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2005, 2, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moberg, M.; Lindqvist, H.; Schäfer Elinder, L.; Norman, Å. Motivational Interviewing in the school setting: Associating school nurses’ skills with children’s behaviour change. Nurs. Rep. 2022; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cicchetti, D.V. Guidelines, Criteria, and Rules of Thumb for Evaluating Normed and Standardized Assessment Instruments in Psychology. Psychol. Assess. 1994, 6, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 27.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo Plus, Version 12; Alfasoft: Göteborg, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.; Guba, E. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malterud, K. Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 2001, 358, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs-Principles and Practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guetterman, T.C.; Fetters, M.D.; Creswell, J.W. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Results in Health Science Mixed Methods Research Through Joint Displays. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wain, R.M.; Kutner, B.A.; Smith, J.L.; Carpenter, K.M.; Hu, M.-C.; Amrhein, P.C.; Nunes, E.V. Self-Report After Randomly Assigned Supervision Does not Predict Ability to Practice Motivational Interviewing. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2015, 57, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pollak, K.I. Incorporating MI techniques into physician counseling. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 84, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madson, M.B.; Mohn, R.S.; Schumacher, J.A.; Landry, A.S. Measuring Client Experiences of Motivational Interviewing during a Lifestyle Intervention. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2015, 48, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Kline, J.A.; Jackson, B.E.; Laureano-Phillips, J.; Robinson, R.D.; Cowden, C.D.; d’Etienne, J.P.; Arze, S.E.; Zenarosa, N.R. Association between emergency physician self-reported empathy and patient satisfaction. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madson, M.B.; Mohn, R.S.; Zuckoff, A.; Schumacher, J.A.; Kogan, J.; Hutchison, S.; Magee, E.; Stein, B. Measuring client perceptions of motivational interviewing: Factor analysis of the Client Evaluation of Motivational Interviewing Scale. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2013, 44, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attended MI Session | Rated MI Sessions | Interviewed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| School Nurses | 7 | 97 | 7 |

| Women | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Mean age | 47 | 47 | 47 |

| Previous MI education (yes) | 3 (43) | 3 (43) | 3 (43) |

| Years active as school nurse | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 |

| Parents | 99 | 65 | 17 |

| Mothers | 65 (65) | 47 (72) | 10 (59) |

| Education level (low) 1 | 27 (27) | 17 (26) | 4 (23) |

| Born outside the Nordic region 2 | 65 (65) | 42 (65) | 11 (65) |

| Children (of participating parents) | 97 | 65 | 17 |

| Girls | 48 (48) | 31 (48) | 9 (53) |

| Mean age | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.3 |

| Weight status (overweight or obesity) 3 | 25 (26) | 18 (28) | 5 (29) |

| Variable and Respondent | n | M (SD) | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivate Change | ||||||

| MITI (1) | 89 | 1.7 (0.8) | 1–4 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| School nurse (2) | 97 | 3.0 (0.8) | 1–5 | 0.06 | 1 | −0.20 |

| Parent (3) | 66 | 4.6 (0.7) | 2–5 | 0.11 | −0.20 | 1 |

| Empathy | ||||||

| MITI (1) | 89 | 2.1 (0.9) | 1–4 | 1 | 0.91 | 0.81 |

| School nurse (2) | 97 | 3.5 (0.8) | 1–5 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.29 * |

| Parent (3) | 66 | 4.7 (0.5) | 3–5 | 0.81 | 0.29 * | 1 |

| Reflections vs. Questions | ||||||

| MITI (1) | 97 | 0.9 (0.5) | 0–2.4 | 1 | 0.41 ** | - |

| Nurse (2) | 97 | 1.8 (0.7) | 1–3 | 0.41 ** | 1 | - |

| Categories | Sub-Categories | Domains | |

|---|---|---|---|

| School Nurses | Parents | ||

| Meeting the other | Shifting power relations in a sensitive meeting | Respectful and professional | |

| Just taking the time to listen and confirm | Person-centred—or not | ||

| Perceived quality | Mastering MI as a method | Motivated and empowered | |

| Challenges and lessons learnt | |||

| Joint Concepts | Correlations | School Nurses’ Perceptions | Parents’ Perceptions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MITI vs. SN (r) | MITI vs. Parent (r) | SN vs. Parent (r) | Generic Category | |||

| Perceived Quality | ||||||

| Recognise and cultivate parents’ motivation Quantitative variables: - Cultivate change talk Qualitative category: - Perceived quality | 0.17 | 0.13 | −0.10 | Sub-categories and quotes | Mastering MI as a method ”I had a hard time finding this change talk, and I ended up in a more supportive role” (School nurse 5) Challenges and lessons learnt “MI was very difficult [with interpreter], I couldn’t do it” (School nurse 1) | Motivated and empowered “It was only after this conversation with the school nurse… I got this commitment, and the motivation to deal with this [healthy behaviour change]” (Father 2) |

| Ability to listen and reflect what parents say Quantitative variables: - Reflections Qualitative category: - Perceived quality | 0.40 ** | n/a | n/a | Mastering MI as a method “Simple reflections are one thing, but when you need to use, what do you call them, advanced reflections, those are somehow more difficult” (School nurse 6) | n/a | |

| Show consideration for parents’ worldview Quantitative variables: - Empathy Qualitative category: - Meeting the other | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.25 * | Shifting power relations in a sensitive meeting “There was no lecturing from me, no finger-wagging from the school nurse so to speak” (School nurse 1) Just taking the time to listen and confirm “So, that’s a little bit what I mean, to be listened to… they [the parents] actually got the chance and the time” (School nurse 2) | Respectful and professional “Yes, she [the school nurse] was amazing, she gives information calmly and it was not stressful and on a good level” (Father 1) Person-centred—or not “It wasn’t like she [the school nurse] was in charge, but I kind of got to talk about what I was experiencing” (Mother 2) | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moberg, M.; Lindqvist, H.; Andermo, S.; Norman, Å. “Sometimes It Felt Great, and Sometimes It Just Went Pear-Shaped”: Experiences and Perceptions of School Nurses’ Motivational Interviewing Competence: A Convergent Mixed-Methods Study. Clin. Pract. 2022, 12, 333-349. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract12030039

Moberg M, Lindqvist H, Andermo S, Norman Å. “Sometimes It Felt Great, and Sometimes It Just Went Pear-Shaped”: Experiences and Perceptions of School Nurses’ Motivational Interviewing Competence: A Convergent Mixed-Methods Study. Clinics and Practice. 2022; 12(3):333-349. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract12030039

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoberg, Marianna, Helena Lindqvist, Susanne Andermo, and Åsa Norman. 2022. "“Sometimes It Felt Great, and Sometimes It Just Went Pear-Shaped”: Experiences and Perceptions of School Nurses’ Motivational Interviewing Competence: A Convergent Mixed-Methods Study" Clinics and Practice 12, no. 3: 333-349. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract12030039

APA StyleMoberg, M., Lindqvist, H., Andermo, S., & Norman, Å. (2022). “Sometimes It Felt Great, and Sometimes It Just Went Pear-Shaped”: Experiences and Perceptions of School Nurses’ Motivational Interviewing Competence: A Convergent Mixed-Methods Study. Clinics and Practice, 12(3), 333-349. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract12030039