A Review of the Literature on the Endocrine Disruptor Activity Testing of Bisphenols in Caenorhabditis elegans

Abstract

1. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: A Significant Concern for Living Organisms

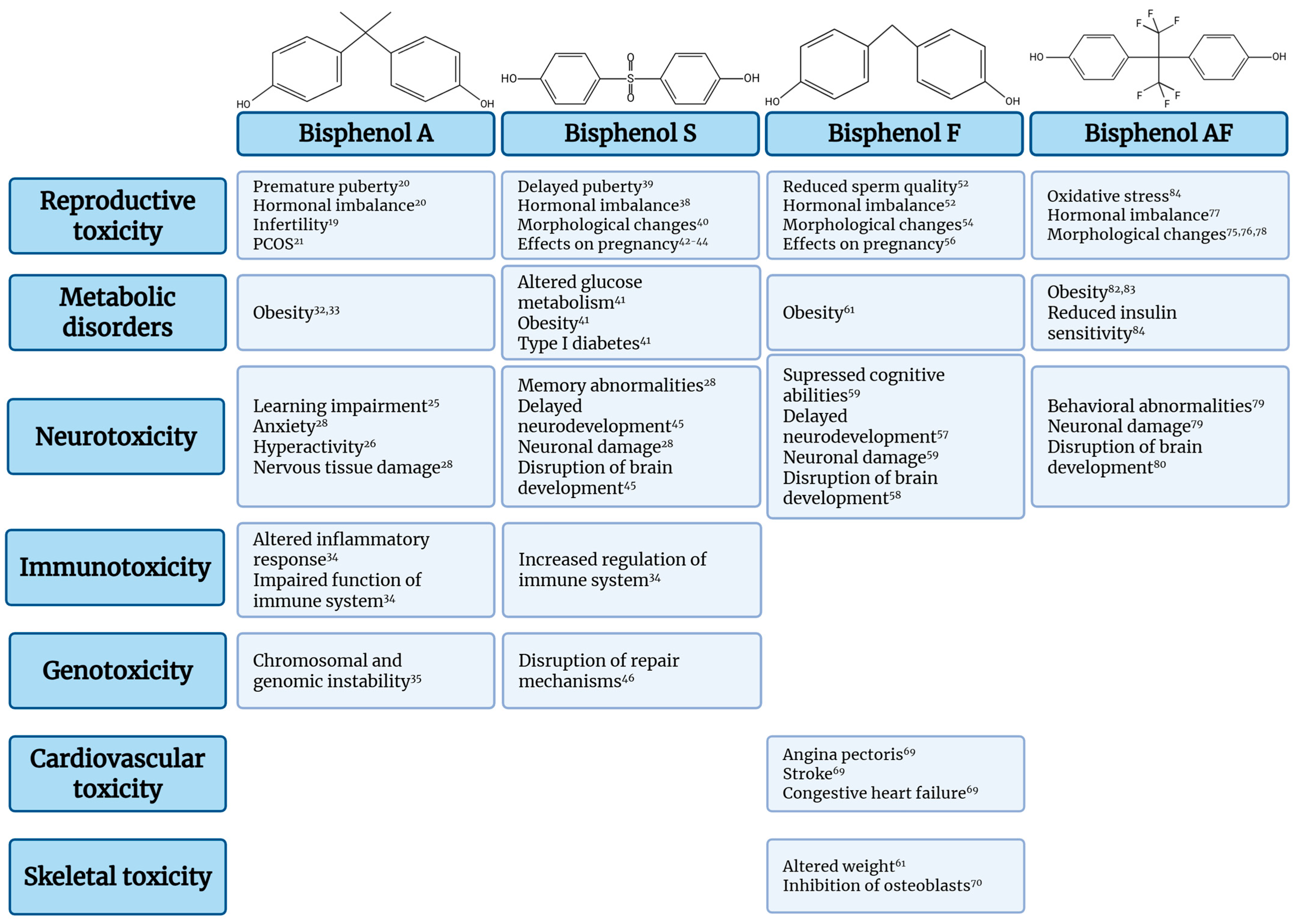

Bisphenols

2. The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans as a Model Organism

2.1. The Endpoints Employed for the Assessment of Toxicity of Bisphenols in C. elegans

2.1.1. Lethality Assay

2.1.2. Growth Rate and Developmental Assay

2.1.3. Reproduction and Lifespan Assay

2.1.4. Transgenerational and Multigenerational Assay

2.1.5. Neurotoxicity Assay

2.1.6. Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage Assay

2.1.7. Apoptosis Assay

| Bisphenol-Relevant Mechanistic Pathway | Representative Mammalian/Human Outcomes Reported for BPA and Analogues | Corresponding C. elegans Endpoints Used for Bisphenol Toxicity | Translational Relevance and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction | BPA, BPS, BPF, and BPAF increase ROS production and antioxidant defenses [38,44,48,56] | ROS-sensitive dyes, reporter strains, oxidative-stress responsive GFP strains, survival [115,130,146,147,153,165,166,168] | Central, conserved mechanism for bisphenol toxicity, high sensitivity in nematodes. Dose–response extrapolation requires caution due to metabolic differences |

| Reproductive and endocrine disruption | BPA, BPS, BPF, and BPAF are associated with infertility [19], PCOS [21], reduced sperm quality [40,52,53,54], altered ovarian function [39,55], and hormone homeostasis [52,72,73] | Brood size, egg-laying rate, germline apoptosis, developmental progression [114,121,130,131,132,133,134] | Conserved germline biology supports translational relevance; however, nematodes lack vertebrate gonadal steroid hormones |

| Neurobehavioral toxicity | Neurodevelopmental impairment [28,45,57], cognitive and behavioral deficits [25,26,27] after bisphenol exposure | Thrashing and body-bend frequency, chemotaxis behavior, pharyngeal pumping [115,120,124,147,153,154,155,164] | Functional neurotoxicity is robustly captured; neurotransmitter-specific effects may need complementary molecular analysis |

| Metabolic dysregulation and obesogenic effects | Bisphenol exposure is associated with increased adiposity [32,33,61,82], insulin resistance [41], and metabolic syndromes [63,64,83] | Growth rate, body bend, lifespan, developmental timing [115,120,121,122,123] | Insulin/IGF-1 signaling is conserved; nematode lipid storage reflects energy homeostasis rather than true adiposity |

| DNA damage | DNA strand breaks, chromosomal instability, and impaired DNA repair [35,38,46] | Comet assay, DNA damage reporter strains, qPCR, meiotic chromosome integrity [130,147,165,167,168] | High mechanistic concordance for DNA damage pathways, cancer risk cannot be directly modeled |

| Transgenerational and epigenetic effects * | BPAF is associated with inherited reproductive, developmental, and behavioral alterations [30,31,42,43,79] | Multigenerational brood size, lifespan, and behavioral assays, reporter strains [120,140,141,142,143] | C. elegans is particularly powerful for tracking inheritance across generations, though epigenetic complexity is reduced compared to mammals |

3. Limitations of Using C. elegans

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| EDC | Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals |

| ADHD | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| BPA | Bisphenol A |

| BPS | Bisphenol S |

| BPF | Bisphenol F |

| BPAF | Bisphenol AF |

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome |

| TBBPA | Tetrabromobisphenol A |

| BPAP | Bisphenol AP |

| BPB | Bisphenol B |

| BPZ | Bisphenol Z |

| NGM | Nematode Growth Medium |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| TCBPA | Tetrachlorobisphenol A |

| TMBPF | Tetramethylbisphenol F |

| BPTMC | Bisphenol TMC |

| CI | Chemotaxis Index |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| GFP | Green Fluorescent Protein |

| BPY | Bisphenol Y |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Assessment on the State of the Science of Endocrine Disruptors. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/67357 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Yilmaz, B.; Terekeci, H.; Sandal, S.; Kelestimur, F. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals: Exposure, Effects on Human Health, Mechanism of Action, Models for Testing and Strategies for Prevention. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2019, 21, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, V.; Pelland-St-Pierre, L.; Gravel, S.; Bouchard, M.F.; Verner, M.A.; Labrèche, F. Endocrine Disruptors: Challenges and Future Directions in Epidemiologic Research. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 111969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Bourguignon, J.P.; Giudice, L.C.; Hauser, R.; Prins, G.S.; Soto, A.M.; Zoeller, R.T.; Gore, A.C. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr. Rev. 2009, 30, 293–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas Zoeller, R.; Brown, T.R.; Doan, L.L.; Gore, A.C.; Skakkebaek, N.E.; Soto, A.M.; Woodruff, T.J.; Vom Saal, F.S. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Public Health Protection: A Statement of Principles from The Endocrine Society. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 4097–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Merrill, M.A.; Vandenberg, L.N.; Smith, M.T.; Goodson, W.; Browne, P.; Patisaul, H.B.; Guyton, K.Z.; Kortenkamp, A.; Cogliano, V.J.; Woodruff, T.J.; et al. Consensus on the Key Characteristics of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals as a Basis for Hazard Identification. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 16, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monisha, R.S.; Mani, R.L.; Sivaprakash, B.; Rajamohan, N.; Vo, D.V.N. Remediation and Toxicity of Endocrine Disruptors: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 21, 1117–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Thacharodi, A.; Priya, A.; Meenatchi, R.; Hegde, T.A.; R, T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Pugazhendhi, A. Endocrine Disruptors: Unravelling the Link between Chemical Exposure and Women’s Reproductive Health. Environ. Res. 2024, 241, 117385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacharodi, A.; Hassan, S.; Acharya, G.; Vithlani, A.; Hoang Le, Q.; Pugazhendhi, A. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals and Their Effects on the Reproductive Health in Men. Environ. Res. 2023, 236, 116825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, I.V.M.; De Albuquerque, F.M.; De Jesus Fernandes, A.; Berti Zanella, P.; Alves Silva, M. Prenatal Exposure to Bisphenol-A and Neurocognitive Changes in Children Aged 2 to 5 Years: A Systematic Review. Rev. Environ. Health 2025, 40, 820–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yuan, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, W. Bisphenol A Exposure and Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Problems in Children under 12 Years of Age: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 490, 137731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, E.J.; Dhurandhar, N.V.; Keith, S.W.; Aronne, L.J.; Barger, J.; Baskin, M.; Benca, R.M.; Biggio, J.; Boggiano, M.M.; Eisenmann, J.C.; et al. Ten Putative Contributors to the Obesity Epidemic. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 868–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, C.; Jeung, E.B. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Disease Endpoints. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumu, K.; Vorst, K.; Curtzwiler, G. Endocrine Modulating Chemicals in Food Packaging: A Review of Phthalates and Bisphenols. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 1337–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luttrell, W.E.; Baird, B.A. Bisphenol, A. J. Chem. Health Saf. 2014, 21, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, M.F.; Tariq, T.; Fatima, B.; Sahar, A.; Tariq, F.; Munir, S.; Khan, S.; Nawaz Ranjha, M.M.A.; Sameen, A.; Zeng, X.A.; et al. An Insight into Bisphenol A, Food Exposure and Its Adverse Effects on Health: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1047827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, J.; Yuan, L.; Wang, Y.; Du, X.; Wang, R.; Marwa, P.W.; Petlulu, P.; Chen, X.; et al. The Adverse Health Effects of Bisphenol A and Related Toxicity Mechanisms. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Lu, G.; Jiang, R.; Yan, Z.; Li, Y. Occurrence, Toxicity and Ecological Risk of Bisphenol A Analogues in Aquatic Environment—A Review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy Abdel-satar, M.; Elgazzar, A.; Alalfy, M.; Abdalrashed, M.; Abdalmageed, A.; Greash, M.; Hamed, S.; Ragab, W.S.; Moustafa Magdi, M. Correlation Study of Urinary BPA in Women with PCOS. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. Appl. Toxicol. 2023, 22, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, J.R. Bisphenol A and Human Health: A Review of the Literature. Reprod. Toxicol. 2013, 42, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanetz, L.A.M.L.; Junior, J.M.S.; Maciel, G.A.R.; Simões, R.d.S.; Baracat, M.C.P.; Baracat, E.C. Does Bisphenol A (BPA) Participates in the Pathogenesis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)? Clinics 2023, 78, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonelli, A.; Guadagni, R.; De Franciscis, P.; Colacurci, N.; Pieri, M.; Basilicata, P.; Pedata, P.; Lamberti, M.; Sannolo, N.; Miraglia, N. Environmental and Occupational Exposure to Bisphenol A and Endometriosis: Urinary and Peritoneal Fluid Concentration Levels. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2017, 90, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitku, J.; Sosvorova, L.; Chlupacova, T.; Hampl, R.; Hill, M.; Sobotka, V.; Heracek, J.; Bicikova, M.; Starka, L. Differences in Bisphenol A and Estrogen Levels in the Plasma and Seminal Plasma of Men with Different Degrees of Infertility. Physiol. Res. 2015, 64, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presunto, M.; Mariana, M.; Lorigo, M.; Cairrao, E. The Effects of Bisphenol A on Human Male Infertility: A Review of Current Epidemiological Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, J.M.; Muckle, G.; Arbuckle, T.; Bouchard, M.F.; Fraser, W.D.; Ouellet, E.; Séguin, J.R.; Oulhote, Y.; Webster, G.M.; Lanphear, B.P. Associations of Prenatal Urinary Bisphenol A Concentrations with Child Behaviors and Cognitive Abilities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 067008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, C.; Mulligan, K. Does Bisphenol A Confer Risk of Neurodevelopmental Disorders? What We Have Learned from Developmental Neurotoxicity Studies in Animal Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I.; Lee, Y.A.; Shin, C.H.; Hong, Y.C.; Kim, B.N.; Lim, Y.H. Association of Bisphenol A, Bisphenol F, and Bisphenol S with ADHD Symptoms in Children. Environ. Int. 2022, 161, 107093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sang, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Gao, H. Effects of Bisphenol A and Bisphenol Analogs on the Nervous System. Chin. Med. J. 2023, 136, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonavane, M.; Gassman, N.R. Bisphenol A Co-Exposure Effects: A Key Factor in Understanding BPA’s Complex Mechanism and Health Outcomes. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2019, 49, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustieles, V.; Zhang, Y.; Yland, J.; Braun, J.M.; Williams, P.L.; Wylie, B.J.; Attaman, J.A.; Ford, J.B.; Azevedo, A.; Calafat, A.M.; et al. Maternal and Paternal Preconception Exposure to Phenols and Preterm Birth. Environ. Int. 2020, 137, 105523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, M.S.; Menon, R.; Yu, G.F.B.; Amosco, M.D. Actions of Bisphenol A on Different Feto-Maternal Compartments Contributing to Preterm Birth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, J.; Wang, F.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, C.; He, J.; Yao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, P.; et al. Association of Serum Bisphenol A Levels with Incident Overweight and Obesity Risk and the Mediating Effect of Adiponectin. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deodati, A.; Bottaro, G.; Germani, D.; Carli, F.; Tait, S.; Busani, L.; Della Latta, V.; Pala, A.P.; Maranghi, F.; Tassinari, R.; et al. Urinary Bisphenol A and Bis(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Metabolite Concentrations in Children with Obesity: A Case-Control Study. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2024, 97, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaisé, Y.; Lencina, C.; Cartier, C.; Olier, M.; Ménard, S.; Guzylack-Piriou, L. Perinatal Oral Exposure to Low Doses of Bisphenol A, S or F Impairs Immune Functions at Intestinal and Systemic Levels in Female Offspring Mice. Environ. Health 2020, 19, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, A.; Moldovan, G.L. Novel Insights into the Role of Bisphenol A (BPA) in Genomic Instability. NAR Cancer 2024, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buoso, E.; Masi, M.; Limosani, R.V.; Oliviero, C.; Saeed, S.; Iulini, M.; Passoni, F.C.; Racchi, M.; Corsini, E. Endocrine Disrupting Toxicity of Bisphenol A and Its Analogs: Implications in the Neuro-Immune Milieu. J. Xenobiotics 2025, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Kannan, K.; Tan, H.; Zheng, Z.; Feng, Y.L.; Wu, Y.; Widelka, M. Bisphenol Analogues Other Than BPA: Environmental Occurrence, Human Exposure, and Toxicity—A Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5438–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food, E.; Authority, S.; Fitzgerald, R.; Loveren, V.; Civitella, C.; Castoldi, A.F.; Bernasconi, G. Assessment of New Information on Bisphenol S (BPS) Submitted in Response to the Decision 1 under REACH Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006. EFSA Support. Publ. 2020, 17, 1844E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maćczak, A.; Cyrkler, M.; Bukowska, B.; Michałowicz, J. Bisphenol A, Bisphenol S, Bisphenol F and Bisphenol AF Induce Different Oxidative Stress and Damage in Human Red Blood Cells (in Vitro Study). Toxicol. Vitr. 2017, 41, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ijaz, S.; Ullah, A.; Shaheen, G.; Jahan, S. Exposure of BPA and Its Alternatives like BPB, BPF, and BPS Impair Subsequent Reproductive Potentials in Adult Female Sprague Dawley Rats. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2020, 30, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eladak, S.; Grisin, T.; Moison, D.; Guerquin, M.J.; N’Tumba-Byn, T.; Pozzi-Gaudin, S.; Benachi, A.; Livera, G.; Rouiller-Fabre, V.; Habert, R. A New Chapter in the Bisphenol A Story: Bisphenol S and Bisphenol F Are Not Safe Alternatives to This Compound. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 103, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Huang, G.; Guo, T.L. Bisphenol S Modulates Type 1 Diabetes Development in Non-Obese Diabetic (NOD) Mice with Diet- and Sex-Related Effects. Toxics 2019, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhao, H.; Braun, J.M.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, B.; Xia, W.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Associations of Trimester-Specific Exposure to Bisphenols with Size at Birth: A Chinese Prenatal Cohort Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Park, E.; Park, E.K.; Lee, S.; Kwon, J.A.; Shin, B.H.; Kang, S.; Park, E.Y.; Kim, B. Urinary Concentrations of Bisphenol Mixtures during Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes: The MAKE Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 10098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Huo, X.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y. Association of Bisphenol A or Bisphenol S Exposure with Oxidative Stress and Immune Disturbance among Unexplained Recurrent Spontaneous Abortion Women. Chemosphere 2020, 257, 127035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Xiong, C.; Sun, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, W.; et al. Prenatal Exposure to Bisphenol A and Its Alternatives and Child Neurodevelopment at 2 Years. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 388, 121774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, V.C.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. DNA Damaging and Apoptotic Potentials of Bisphenol A and Bisphenol S in Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 60, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Tang, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; He, H.; Du, B.; et al. Bisphenol F Suppresses Insulin-Stimulated Glucose Metabolism in Adipocytes by Inhibiting IRS-1/PI3K/AKT Pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 231, 113201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Liu, C.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Pan, A.; Yang, P.; Chen, Y.J.; Deng, Y.L.; Lu, Q.; Cheng, L.M.; et al. Urinary Levels of Bisphenol A, F and S and Markers of Oxidative Stress among Healthy Adult Men: Variability and Association Analysis. Environ. Int. 2019, 123, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman, A.; Ikhlas, S.; Ahmad, M. Occurrence, Toxicity and Endocrine Disrupting Potential of Bisphenol-B and Bisphenol-F: A Mini-Review. Toxicol. Lett. 2019, 312, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Xie, J.; Mao, L.; Zhao, M.; Bai, X.; Wen, J.; Shen, T.; Wu, P. Bisphenol Analogue Concentrations in Human Breast Milk and Their Associations with Postnatal Infant Growth. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 113779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; An, K.S.; Kim, H.J.; Noh, H.J.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, J.; Song, K.S.; Chae, C.; Ryu, H.Y. Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity Evaluation Following Oral Exposure to Bisphenol F. Arch. Toxicol. 2022, 96, 1711–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odetayo, A.F.; Adeyemi, W.J.; Olayaki, L.A. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ameliorates Bisphenol F-Induced Testicular Toxicity by Modulating Nrf2/NFkB Pathway and Apoptotic Signaling. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1256154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odetayo, A.F.; Adeyemi, W.J.; Olayaki, L.A. In Vivo Exposure to Bisphenol F Induces Oxidative Testicular Toxicity: Role of Erβ and P53/Bcl-2 Signaling Pathway. Front. Reprod. Health 2023, 5, 1204728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Z.M.; Chen, Y.W.; Ahmad, M.J.; Wang, Y.S.; Yang, S.J.; Duan, Z.Q.; Liu, M.; Yang, C.X.; Liang, A.X.; Hua, G.H.; et al. Bisphenol F Exposure Affects Mouse Oocyte In Vitro Maturation through Inducing Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage. Environ. Toxicol. 2022, 37, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algonaiman, R.; Almutairi, A.S.; Al Zhrani, M.M.; Barakat, H.; Algonaiman, R.; Almutairi, A.S.; Al Zhrani, M.M.; Barakat, H. Effects of Prenatal Exposure to Bisphenol A Substitutes, Bisphenol S and Bisphenol F, on Offspring’s Health: Evidence from Epidemiological and Experimental Studies. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Yuan, L.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Qiu, J. Bisphenol F Impaired Zebrafish Cognitive Ability through Inducing Neural Cell Heterogeneous Responses. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 8528–8540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Sun, S.; Chen, L.; Lv, L.; Chen, C.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, A.; He, H.; Tao, H.; Yu, M.; et al. The Association between Prenatal Bisphenol F Exposure and Infant Neurodevelopment: The Mediating Role of Placental Estradiol. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 271, 116009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Wu, J.; Xu, S.; Zhang, L.; Fan, D.; Shi, L.; Wang, J.; Ji, G. Bisphenol F Exposure Impairs Neurodevelopment in Zebrafish Larvae (Danio Rerio). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 188, 109870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina-Pérez, I.; Olivas-Martínez, A.; Mustieles, V.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Molina-Molina, J.M.; Olea, N.; Fernández, M.F. Bisphenol F and Bisphenol S Promote Lipid Accumulation and Adipogenesis in Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 152, 112216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, V.A.; Clark, K.C.; Carrillo-Sáenz, L.; Holl, K.A.; Velez-Bermudez, M.; Simonsen, D.; Grobe, J.L.; Wang, K.; Thurman, A.; Solberg Woods, L.C.; et al. Bisphenol F Exposure in Adolescent Heterogeneous Stock Rats Affects Growth and Adiposity. Toxicol. Sci. 2021, 181, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.H.; Woodward, M.; Bao, W.; Liu, B.; Trasande, L. Urinary Bisphenols and Obesity Prevalence Among U.S. Children and Adolescents. J. Endocr. Soc. 2019, 3, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancière, F.; Botton, J.; Slama, R.; Lacroix, M.Z.; Debrauwer, L.; Charles, M.A.; Roussel, R.; Balkau, B.; Magliano, D.J.; Balkau, B.; et al. Exposure to Bisphenol A and Bisphenol s and Incident Type 2 Diabetes: A Case-Cohort Study in the French Cohort D.E.S.I.R. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 107013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Qian, L.; Qian, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, K.; Huang, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Mu, X. Bisphenol F-Induced Neurotoxicity toward Zebrafish Embryos. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 14638–14648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qi, S.; Mu, X.; Yuan, L.; Li, Y.; Qiu, J. Bisphenol F Induces Liver-Gut Alteration in Zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 157974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, S.; Jin, H.; Tang, L.; Xia, M. Associations of Bisphenol F and S, as Substitutes for Bisphenol A, with Cardiovascular Disease in American Adults. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2023, 43, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Recio, E.; Costela-Ruiz, V.J.; Illescas-Montes, R.; Melguizo-Rodríguez, L.; García-Martínez, O.; Ruiz, C.; De Luna-Bertos, E. Modulation of Osteogenic Gene Expression by Human Osteoblasts Cultured in the Presence of Bisphenols BPF, BPS, or BPAF. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catenza, C.J.; Farooq, A.; Shubear, N.S.; Donkor, K.K. A Targeted Review on Fate, Occurrence, Risk and Health Implications of Bisphenol Analogues. Chemosphere 2021, 268, 129273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escrivá, L.; Zilliacus, J.; Hessel, E.; Beronius, A. Assessment of the Endocrine Disrupting Properties of Bisphenol AF: A Case Study Applying the European Regulatory Criteria and Guidance. Environ. Health 2021, 20, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Yang, C.; Zhu, J.; Ling, Y.; Kuang, H. Gestational Exposure to Bisphenol AF Causes Endocrine Disorder of Corpus Luteum by Altering Ovarian SIRT-1/Nrf2/NF-KB Expressions and Macrophage Proangiogenic Function in Mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 220, 115954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.; Tang, W.; Shen, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, J. Exposure to Bisphenol A and Its Analogs and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome in Women of Childbearing Age: A Multicenter Case-Control Study. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, H.; Yang, X.; Wu, X.; Tian, Y.; Xu, P.; Sang, N. Identification of Risk for Ovarian Disease Enhanced by BPB or BPAF Exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 319, 120980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Yang, X.; Tian, Y.; Xu, P.; Yue, H.; Sang, N. Bisphenol B and Bisphenol AF Exposure Enhances Uterine Diseases Risks in Mouse. Environ. Int. 2023, 173, 107858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Su, S.; Wei, X.; Wang, S.; Guo, T.; Li, J.; Song, H.; Wang, M.; Wang, Z. Exposure to Bisphenol A Alternatives Bisphenol AF and Fluorene-9-Bisphenol Induces Gonadal Injuries in Male Zebrafish. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 253, 114634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Liu, L.; Dong, M.; Xue, W.; Zhou, S.; Li, X.; Guo, S.; Yan, W. Prenatal Exposure to Bisphenol AF Induced Male Offspring Reproductive Dysfunction by Triggering Testicular Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 259, 115030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Gu, J.; Yin, X.; Guo, L.; Qian, L.; Shi, L.; Guo, M.; Ji, G. The Toxic Effect of Bisphenol AF and Nanoplastic Coexposure in Parental and Offspring Generation Zebrafish. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 251, 114565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, S.; Ni, Y.; Qi, C.; Bai, S.; Xu, Q.; Fan, Y.; Ma, X.; Lu, C.; Du, G.; et al. Maternal BPAF Exposure Impaired Synaptic Development and Caused Behavior Abnormality in Offspring. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 256, 114859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, J.; Ding, J.; Liu, J. Neurodevelopmental Toxicity of Bisphenol AF in Zebrafish Larvae and the Protective Effects of Curcumin. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2023, 43, 1806–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernis, N.; Masschelin, P.; Cox, A.R.; Hartig, S.M. Bisphenol AF Promotes Inflammation in Human White Adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2020, 318, C63–C72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Lv, C.; Zhang, S.; Tse, L.A.; Hong, X.; Liu, X.; Ding, Y.; Xiao, P.; Tian, Y.; Gao, Y. Bisphenol A Substitutes and Childhood Obesity at 7 Years: A Cross-Sectional Study in Shandong, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 73174–73184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Tzioufa, F.; Bruton, J.; Westerblad, H.; Munic Kos, V. The Impact of Bisphenol AF on Skeletal Muscle Function and Differentiation in Vitro. Toxicology 2025, 103, 105975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimah, E.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, M.; Xu, H.; Mensah, J.K.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gyimah, G.N.W. Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis in Bisphenol AF–Induced Neurotoxicity in Zebrafish Embryos. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2022, 41, 2273–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, P.R. The C. elegans Model in Toxicity Testing. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2017, 37, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartung, T. Toxicology for the Twenty-First Century. Nature 2009, 460, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, P.R.; Camacho, J.A.; Sprando, R.L. Caenorhabditis elegans for Predictive Toxicology. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2020, 23–24, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, W.T.; Stanslas, J. The New Paradigm in Animal Testing—“3Rs Alternatives”. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 153, 105705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.M.; Tran, S.H.; Shim, Y.H.; Kang, K. Caenorhabditis elegans as a Powerful Tool in Natural Product Bioactivity Research. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2022, 65, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ezemaduka, A.N.; Tang, Y.; Chang, Z. Understanding the Mechanism of the Dormant Dauer Formation of C. elegans: From Genetics to Biochemistry. IUBMB Life 2009, 61, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Cabana, A.; Romero-Expósito, F.J.; Geibel, M.; Piubeli, F.A.; Merrow, M.; Olmedo, M. Deviations from Temporal Scaling Support a Stage-Specific Regulation for C. elegans Postembryonic Development. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muschiol, D.; Schroeder, F.; Traunspurger, W. Life Cycle and Population Growth Rate of Caenorhabditis elegans Studied by a New Method. BMC Ecol. 2009, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indong, R.A.; Park, J.M.; Hong, J.K.; Lyou, E.S.; Han, T.; Hong, J.K.; Lee, T.K.; Lee, J.I. A Simple Protocol for Cultivating the Bacterivorous Soil Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans in Its Natural Ecology in the Laboratory. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1347797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome Sequence of the Nematode C. elegans: A Platform for Investigating Biology. Science 1998, 282, 2012–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.C.K.; Williams, P.L.; Benedetto, A.; Au, C.; Helmcke, K.J.; Aschner, M.; Meyer, J.N. Caenorhabditis elegans: An Emerging Model in Biomedical and Environmental Toxicology. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 106, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.; Ge, L. The Worm in Us—Caenorhabditis elegans as a Model of Human Disease. Trends Biotechnol. 2002, 20, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.C.; Bailey, D.C.; Fitsanakis, V.A. Caenorhabditis elegans as a Model to Assess Reproductive and Developmental Toxicity. In Reproductive and Developmental Toxicology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, L.; Shen, X.; Kong, L.; Wu, T. Research Advances on the Adverse Effects of Nanomaterials in a Model Organism, Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 2406–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, K.; Kucharíková, S.; Bárdyová, Z.; Botek, N.; Kaiglová, A. Applications of a Powerful Model Organism Caenorhabditis elegans to Study the Neurotoxicity Induced by Heavy Metals and Pesticides. Physiol. Res. 2023, 72, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istiban, M.N.; De Fruyt, N.; Kenis, S.; Beets, I. Evolutionary Conserved Peptide and Glycoprotein Hormone-like Neuroendocrine Systems in C. elegans. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2024, 584, 112162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielenbach, N.; Antebi, A. C. elegans Dauer Formation and the Molecular Basis of Plasticity. Genes. Dev. 2008, 22, 2149–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Dabaja, M.; Akhlaq, A.; Pereira, B.; Marbach, K.; Rovcanin, M.; Chandra, R.; Caballero, A.; Fernandes de Abreu, D.; Ch’ng, Q.L.; et al. Specific Sensory Neurons and Insulin-like Peptides Modulate Food Type-Dependent Oogenesis and Fertilization in Caenorhabditis elegans. Elife 2023, 12, e83224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zečić, A.; Braeckman, B.P. DAF-16/FoxO in Caenorhabditis elegans and Its Role in Metabolic Remodeling. Cells 2020, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerisch, B.; Rottiers, V.; Li, D.; Motola, D.L.; Cummins, C.L.; Lehrach, H.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Antebi, A. A Bile Acid-like Steroid Modulates Caenorhabditis elegans Lifespan through Nuclear Receptor Signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 5014–5019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, L.; Pereira, J.L.; Gonçalves, F.J.M.; Pacheco, M.; Aschner, M.; Pereira, P. Caenorhabditis elegans as a Tool for Environmental Risk Assessment: Emerging and Promising Applications for a “Nobelized Worm”. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2019, 49, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, N.P.; Kang, J.S.; Kim, H.M. Caenorhabditis elegans: A Model Organism in the Toxicity Assessment of Environmental Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 39273–39287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, H.; Hua, X.; Wang, C.; Dong, C.; Xie, D.; Tan, S.; Xiang, M.; Li, H. A Review of the Reproductive Toxicity of Environmental Contaminants in Caenorhabditis elegans. Hyg. Environ. Health Adv. 2022, 3, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, S.; Jing, H.; Qi, L.; Ning, J.; Tan, Z.; Yang, K.; Zhao, C.; Ma, L.; Li, G. Correlation of Chemical Acute Toxicity between the Nematode and the Rodent. Toxicol. Res. 2013, 2, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Q.; Li, M.; Liu, H.; Sun, L.; Gao, W.; Wang, D. Adverse Effects from Clenbuterol and Ractopamine on Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and the Underlying Mechanism. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrit, F.R.G.; Ratnappan, R.; Keith, S.A.; Ghazi, A. The C. elegans Lifespan Assay Toolkit. Methods 2014, 68, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ficociello, G.; Gerardi, V.; Uccelletti, D.; Setini, A. Molecular and Cellular Responses to Short Exposure to Bisphenols A, F, and S and Eluates of Microplastics in C. elegans. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Espiñeira, M.C.; Tejeda-Benítez, L.P.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Toxic Effects of Bisphenol A, Propyl Paraben, and Triclosan on Caenorhabditis elegans. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornos Carneiro, M.F.; Shin, N.; Karthikraj, R.; Barbosa, F.; Kannan, K.; Colaiácovo, M.P. Antioxidant CoQ10 Restores Fertility by Rescuing Bisphenol A-Induced Oxidative DNA Damage in the Caenorhabditis elegans Germline. Genetics 2020, 214, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Yang, J.; Li, H.; Cui, C.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lin, K. The Chronic Toxicity of Bisphenol A to Caenorhabditis elegans after Long-Term Exposure at Environmentally Relevant Concentrations. Chemosphere 2016, 154, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamba, N.; Jie, L.; Wei, Z.X.; Qin, Z.C.; SARPONG, F.; Hua, Z.X.; HAMAMBA, N.; Jie, L.; Wei, Z.X.; Qin, Z.C.; et al. Effects of Treatment with Different Combinations of Bisphenol Compounds on the Mortality of Caenorhabditis elegans. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2020, 33, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. Avoidance Behavior of Nematodes to Environmental Toxicants or Stresses. In Target Organ Toxicology in Caenorhabditis elegans; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 27–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Nie, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dai, H.; Wang, J.; Si, B.; Yang, Z.; Cheng, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; et al. Transgenerational Effects of Diesel Particulate Matter on Caenorhabditis elegans through Maternal and Multigenerational Exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 170, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Parra-Guerra, A.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Toxicity of Nonylphenol and Nonylphenol Ethoxylate on Caenorhabditis elegans. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 187, 109709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, X. Toxicity and Multigenerational Effects of Bisphenol S Exposure to Caenorhabditis elegans on Developmental, Biochemical, Reproductive and Oxidative Stress. Toxicol. Res. 2019, 8, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, M.; Rathor, L.; Kim, H.J.; McElroy, T.; Hwang, K.H.; Wohlgemuth, S.; Curry, S.; Xiao, R.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Heo, J.D.; et al. Comparative Toxicities of BPA, BPS, BPF, and TMBPF in the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and Mammalian Fibroblast Cells. Toxicology 2021, 461, 152924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharíková, S.; Hockicková, P.; Melnikov, K.; Bárdyová, Z.; Kaiglová, A. The Caenorhabditis elegans Cuticle Plays an Important Role against Toxicity to Bisphenol A and Bisphenol S. Toxicol. Rep. 2023, 10, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiglová, A.; Bárdyová, Z.; Hockicková, P.; Zvolenská, A.; Melnikov, K.; Kucharíková, S. Caenorhabditis elegans as a Model to Assess the Potential Risk to Human Health Associated with the Use of Bisphenol A and Its Substitutes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Luo, Q.; Cao, X.; Cui, C.; Lin, K.; Huang, K. Toxicological Assessment and Underlying Mechanisms of Tetrabromobisphenol A Exposure on the Soil Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Chemosphere 2020, 242, 125078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Shen, L. Confirmation of Combinational Effects of Calcium with Other Metals in a Paper Recycling Mill Effluent on Nematode Lifespan with Toxicity Identification Evaluation Method. J. Environ. Sci. 2010, 22, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, A.; Pohl, F.; Egan, B.M.; Kocsisova, Z.; Kornfeld, K. Reproductive Aging in Caenorhabditis elegans: From Molecules to Ecology. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 718522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, A.K.; Golden, A.; Conway, S.J.; Camacho, J.A.; Welch, B.; Sprando, R.L.; Hunt, P.R. Reproductive-Toxicity-Related Endpoints in C. elegans Are Consistent with Reduced Concern for Dimethylarsinic Acid Exposure Relative to Inorganic Arsenic. J. Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, Y.; Kickhoefer, V.A.; Rome, L.H.; Allard, P.; Mahendra, S. A Vault-Encapsulated Enzyme Approach for Efficient Degradation and Detoxification of Bisphenol A and Its Analogues. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 5808–5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, P.; Colaiácovo, M.P. Bisphenol A Impairs the Double-Strand Break Repair Machinery in the Germline and Causes Chromosome Abnormalities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 20405–20410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Shu, L.; Qiu, Z.; Lee, D.Y.; Settle, S.J.; Que Hee, S.; Telesca, D.; Yang, X.; Allard, P. Exposure to the BPA-Substitute Bisphenol S Causes Unique Alterations of Germline Function. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Hua, X.; Chen, H.; Yang, Y.; Dang, Y.; Xiang, M. Tetrachlorobisphenol A Mediates Reproductive Toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans via DNA Damage-Induced Apoptosis. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A.H.; Bowen, J.E.; Zhou, X.; Burke, I.; Wenaas, M.H.; Blake, T.A.; Timmons, S.C.; Kuzmanov, A. Synthesis and Reproductive Toxicity of Bisphenol A Analogs with Cyclic Side Chains in Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2022, 38, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathor, L.; Lee, H.J.; McElroy, T.; Beck, S.; Bailey, J.; Wohlgemuth, S.; Kim, S.-H.; Heo, J.; Xiao, R.; Han, S.M.; et al. Bisphenol TMC Disturbs Mitochondrial Activity and Biogenesis, Reducing Lifespan and Healthspan in the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.E.H.; Jung, Y.; Lee, S.J.V. Survival Assays Using Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Cells 2017, 40, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Dou, T.T.; Chen, J.Y.; Duan, M.X.; Zhen, Q.; Wu, H.Z.; Zhao, Y.L. Sublethal Toxicity of Graphene Oxide in Caenorhabditis elegans under Multi-Generational Exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 229, 113064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuda-Durán, B.; Garzón-García, L.; González-Manzano, S.; Santos-Buelga, C.; González-Paramás, A.M. Insights into the Neuroprotective Potential of Epicatechin: Effects against Aβ-Induced Toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Moon, J.; An, Y.J. Matricidal Hatching Can Induce Multi-Generational Effects in Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans after Dietary Exposure to Nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 36394–36402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Pu, X.; Wang, D. A Review of Transgenerational and Multigenerational Toxicology in the in Vivo Model Animal Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2023, 43, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, J.; Truong, L.; Kurt, Z.; Chen, Y.W.; Morselli, M.; Gutierrez, G.; Pellegrini, M.; Yang, X.; Allard, P. The Memory of Environmental Chemical Exposure in C. elegans Is Dependent on the Jumonji Demethylases Jmjd-2 and Jmjd-3/Utx-1. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 2392–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonough, C.M.; Guo, D.J.; Guo, T.L. Developmental Toxicity of Bisphenol S in Caenorhabditis elegans and NODEF Mice. Neurotoxicology 2021, 87, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, K.; Cao, X.; Cui, C.; Lin, K.; Zhang, M. Trans-Generational Effect of Neurotoxicity and Related Stress Response in Caenorhabditis elegans Exposed to Tetrabromobisphenol A. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 134920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Cao, X.; Tian, F.; Jiang, J.; Lin, K.; Cheng, J.; Hu, X. Continuous and Discontinuous Multi-Generational Disturbances of Tetrabromobisphenol A on Longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 251, 114522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xing, X. Assessment of Locomotion Behavioral Defects Induced by Acute Toxicity from Heavy Metal Exposure in Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 20, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, F.; Zhou, T.; Wang, G.; Li, Z. Caenorhabditis elegans as a Useful Model for Studying Aging Mutations. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 554994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, F.; Chen, C.; Aschner, M. Neurotoxicity Evaluation of Nanomaterials Using C. elegans: Survival, Locomotion Behaviors, and Oxidative Stress. Curr. Protoc. 2022, 2, e496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gai, T.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Wang, S.; Ye, T.; Zhang, W. Neurotoxicity of Bisphenol A Exposure on Caenorhabditis elegans Induced by Disturbance of Neurotransmitter and Oxidative Damage. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 252, 114617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, S.D.; Sattelle, D.B. Fast, Automated Measurement of Nematode Swimming (Thrashing) without Morphometry. BMC Neurosci. 2009, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petratou, D.; Fragkiadaki, P.; Lionaki, E.; Tavernarakis, N. Assessing Locomotory Rate in Response to Food for the Identification of Neuronal and Muscular Defects in C. elegans. STAR Protoc. 2023, 5, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, I.; Le, D.T.; von Mikecz, A. How to Keep up with the Analysis of Classic and Emerging Neurotoxins: Age-Resolved Fitness Tests in the Animal Model Caenorhabditis elegans—A Step-by-Step Protocol. EXCLI J. 2022, 21, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Ji, X.; Qiao, K. Oxidative Stress, Intestinal Damage, and Cell Apoptosis: Toxicity Induced by Fluopyram in Caenorhabditis elegans. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, S.; Chen, W. Automated Recognition and Analysis of Head Thrashes Behavior in C. elegans. BMC Bioinform. 2022, 23, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; He, M.; Liu, D. Bisphenol A Exposure Accelerated the Aging Process in the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxicol. Lett. 2015, 235, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; An, J.; Wang, Y.; Shang, Y. The Joint Effects of Nanoplastics and TBBPA on Neurodevelopmental Toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxicol. Res. 2023, 12, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Tan, S.; Guo, H.; Hua, X.; Chen, H.; Yang, Y.; Xie, D.; Yi, C.; Ling, H.; Xiang, M. Chronic Neurotoxicity of Tetrabromobisphenol A: Induction of Oxidative Stress and Damage to Neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans. Chemosphere 2024, 350, 141142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margie, O.; Palmer, C.; Chin-Sang, I. C. elegans Chemotaxis Assay. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 2013, e50069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, H.; Floyd, K.G.; Burnell, D.; Hancock, J.T.; Allainguillaume, J.; Ladomery, M.R.; Wilson, I.D. Residual Ground-Water Levels of the Neonicotinoid Thiacloprid Perturb Chemosensing of Caenorhabditis elegans. Ecotoxicology 2017, 26, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombie, T.A.; Chikuturudzi, C.; Cook, D.E.; Andersen, E.C. An Automated Approach to Quantify Chemotaxis Index in C. elegans. Micro. Publ. Biol 2022, 2022, 10-17912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, L.; Shi, H.; Yan, Y.; Han, Y.; Fang, M.; Liu, Y.; Wu, C.; Fan, S.; et al. Mulberrin Extends Lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans through Detoxification Function. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2024, 44, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ijomone, O.M.; Gubert, P.; Okoh, C.O.A.; Varão, A.M.; Amaral, L.d.O.; Aluko, O.M.; Aschner, M. Application of Fluorescence Microscopy and Behavioral Assays to Demonstrating Neuronal Connectomes and Neurotransmitter Systems in C. elegans. Neuromethods 2021, 172, 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaur, A.V.; Agarwal, R. Risperidone Induced Alterations in Feeding and Locomotion Behavior of Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 2, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, W.A.; McBride, S.J.; Freedman, J.H. Effects of Genetic Mutations and Chemical Exposures on Caenorhabditis elegans Feeding: Evaluation of a Novel, High-Throughput Screening Assay. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejeda-Benitez, L.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Caenorhabditis elegans, a Biological Model for Research in Toxicology. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2016, 237, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohra, S.; Kuwahara, K.; Takao, Y.; Ishibashi, Y.; Ho, C.L.; Arizono, K.; Tominagae, N. Effect of Bisphenol A on the Feeding Behavior of Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Health Sci. 2002, 48, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, H.; Hua, X.; Dang, Y.; Han, Y.; Yu, Z.; Chen, X.; Ding, P.; Li, H. Polystyrene Microplastics (PS-MPs) Toxicity Induced Oxidative Stress and Intestinal Injury in Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 726, 138679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Jin, T.; Li, H.; Long, H.; Liu, Y.; Jin, S.; Lu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, L.; et al. Cannabidivarin Alleviates α-Synuclein Aggregation via DAF-16 in Caenorhabditis elegans. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e22735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanikia, S.; Galea, F.; Nagy, E.; Phillips, D.H.; Stürzenbaum, S.R.; Arlt, V.M. The Application of the Comet Assay to Assess the Genotoxicity of Environmental Pollutants in the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 45, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, B.R.; Briand, N.E.; Fassnacht, N.; Gervasio, E.D.; Nowakowski, A.M.; FitzGibbon, T.C.; Maurina, S.; Benjamin, A.V.; Kelly, M.E.; Checchi, P.M. Counteracting Environmental Chemicals with Coenzyme Q10: An Educational Primer for Use with “Antioxidant CoQ10 Restores Fertility by Rescuing Bisphenol A-Induced Oxidative DNA Damage in the Caenorhabditis elegans Germline”. Genetics 2020, 216, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D. Ecotoxicity of Bisphenol S to Caenorhabditis elegans by Prolonged Exposure in Comparison with Bisphenol A. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 2560–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.; Cuenca, L.; Karthikraj, R.; Kannan, K.; Colaiácovo, M.P. Assessing Effects of Germline Exposure to Environmental Toxicants by High-Throughput Screening in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1007975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, D.; Ding, Y.; Yu, H.Q. Environmentally Relevant Exposure to Tetrabromobisphenol a Induces Reproductive Toxicity via Regulating Glucose-6-Phosphate 1-Dehydrogenase and Sperm Activation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Qiu, Y.; Kong, Y.; Wang, D. Amino Modification Enhances Reproductive Toxicity of Nanopolystyrene on Gonad Development and Reproductive Capacity in Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 112978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germoglio, M.; Adamo, A.; Incerti, G.; Cartenì, F.; Gigliotti, S.; Storlazzi, A.; Mazzoleni, S. Self-DNA Exposure Induces Developmental Defects and Germline DNA Damage Response in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biology 2022, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, B.R.; Whidden, E.; Gervasio, E.D.; Checchi, P.M.; Raley-Susman, K.M. Neonicotinoid-Containing Insecticide Disruption of Growth, Locomotion, and Fertility in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreman, J.; Lee, O.; Trznadel, M.; David, A.; Kudoh, T.; Tyler, C.R. Acute Toxicity, Teratogenic, and Estrogenic Effects of Bisphenol A and Its Alternative Replacements Bisphenol S, Bisphenol F, and Bisphenol AF in Zebrafish Embryo-Larvae. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 12796–12805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhouse, C.; Truong, L.; Meyer, J.N.; Allard, P. Caenorhabditis elegans as an Emerging Model System in Environmental Epigenetics. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2018, 59, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harlow, P.H.; Perry, S.J.; Stevens, A.J.; Flemming, A.J. Comparative Metabolism of Xenobiotic Chemicals by Cytochrome P450s in the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, P.R.; Olejnik, N.; Sprando, R.L. Toxicity Ranking of Heavy Metals with Screening Method Using Adult Caenorhabditis elegans and Propidium Iodide Replicates Toxicity Ranking in Rat. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 3280–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruszkiewicz, J.A.; Pinkas, A.; Miah, M.R.; Weitz, R.L.; Lawes, M.J.A.; Akinyemi, A.J.; Ijomone, O.M.; Aschner, M. C. elegans as a Model in Developmental Neurotoxicology. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018, 354, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Xu, H.; Liang, X.; Tang, M. Caenorhabditis elegans as a Complete Model Organism for Biosafety Assessments of Nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2019, 221, 708–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimoto, A.; Fujii, M.; Usami, M.; Shimamura, M.; Hirabayashi, N.; Kaneko, T.; Sasagawa, N.; Ishiura, S. Identification of an Estrogenic Hormone Receptor in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 364, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunti, S.; Andersen, N.; Rayes, D.; De Rosa, M.J. Drug Discovery: Insights from the Invertebrate Caenorhabditis elegans. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2021, 9, e00721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buoso, E.; Kenda, M.; Masi, M.; Linciano, P.; Galbiati, V.; Racchi, M.; Dolenc, M.S.; Corsini, E. Effects of Bisphenols on RACK1 Expression and Their Immunological Implications in THP-1 Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 743991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahović, P.Š.; Iulini, M.; Maddalon, A.; Galbiati, V.; Buoso, E.; Dolenc, M.S.; Corsini, E. In Vitro Effects of Bisphenol Analogs on Immune Cells Activation and Th Differentiation. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2023, 23, 1750–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambré, C.; Barat Baviera, J.M.; Bolognesi, C.; Chesson, A.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Crebelli, R.; Gott, D.M.; Grob, K.; Lampi, E.; Mengelers, M.; et al. Re-Evaluation of the Risks to Public Health Related to the Presence of Bisphenol A (BPA) in Foodstuffs. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e06857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benian, G.M.; Epstein, H.F. Caenorhabditis elegans Muscle: A Genetic and Molecular Model for Protein Interactions in the Heart. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 1082–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGary, K.L.; Park, T.J.; Woods, J.O.; Cha, H.J.; Wallingford, J.B.; Marcotte, E.M. Systematic Discovery of Nonobvious Human Disease Models through Orthologous Phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Pears, C.; Woollard, A. An Enhanced C. elegans Based Platform for Toxicity Assessment. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hockicková, P.; Kaiglová, A.; Korabečná, M.; Kucharíková, S. A Review of the Literature on the Endocrine Disruptor Activity Testing of Bisphenols in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Xenobiot. 2026, 16, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010007

Hockicková P, Kaiglová A, Korabečná M, Kucharíková S. A Review of the Literature on the Endocrine Disruptor Activity Testing of Bisphenols in Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2026; 16(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleHockicková, Patrícia, Alžbeta Kaiglová, Marie Korabečná, and Soňa Kucharíková. 2026. "A Review of the Literature on the Endocrine Disruptor Activity Testing of Bisphenols in Caenorhabditis elegans" Journal of Xenobiotics 16, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010007

APA StyleHockicková, P., Kaiglová, A., Korabečná, M., & Kucharíková, S. (2026). A Review of the Literature on the Endocrine Disruptor Activity Testing of Bisphenols in Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Xenobiotics, 16(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010007