Structural and Dynamic Insights into Podocalyxin–Ezrin Interaction as a Target in Cancer Progression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Molecular Modelling Tools and Their Applications

2.2. Structural Modelling and Optimisation for the PODXL–Ezrin Complex

2.3. In Silico Mutagenesis of PODXL (R495W Variant with Potential Impact on Ezrin Binding)

2.4. Wild-Type and R495W PODXL–Ezrin Complex Modelling and Stereochemical Validation

2.5. System Preparation and Molecular Dynamics Simulations of PODXLWT–Ezrin and PODXLR495W–Ezrin Complexes

2.6. Structural Analysis and Visualisation of Docking and MD Results

2.7. Virtual Screening Workflow for Inhibitor Identification

2.8. MD Simulations and Analysis of Ligand-Bound Complexes

3. Results

3.1. Structural Modelling and Validation of PODXL and Ezrin

3.2. Structural Insights into PODXLWT–Ezrin Interactions and the Impact of the R495W Mutation on Complex Stability

3.3. Structural Dynamics and Mutation-Induced Stability of the PODXL–Ezrin Complex

3.4. Inter-Residue Distance Analysis Reveals Key Stabilising Interactions in the PODXLWT–Ezrin Complex, with Arg495:HH22–Asp31:OD1 Contributing to Initial Complex Formation

3.5. The R495W Mutation Introduces Conformational Tension in the PODXLR495W–Ezrin Complex and Exposes Sites for Potential Ezrin Activation

3.6. R495W Mutation Promotes Stronger Engagement with Ezrin’s Pre-C-Terminal Loop in the PODXLR495W–Ezrin Complex

3.7. Virtual Screening and Hit Identification Against the Wild-Type PODXL–Ezrin Complex

3.8. Docking Reveals Differential Binding Efficacies Against Wild-Type and Mutant PODXL–Ezrin Complexes

3.9. Structural Dynamics Analysis of Drug-Bound PODXL–Ezrin Complexes

3.10. Centre of Mass Distance Analysis Reveals Distinct Drug Positioning Between Wild-Type and Mutant Complexes

3.11. Root Mean Square Deviation Analysis Demonstrates Mutation-Dependent Drug Effects on Complex Stability

3.12. Root Mean Square Fluctuation Analysis Reveals Region-Specific Flexibility Modulation by Drug Binding

3.13. Radius of Gyration Analysis Indicates Differential Drug-Mediated Compaction Between Wild-Type and Mutant States

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PODXL | Podocalyxin |

| WT | Wild-type |

| R495W/MT | Substitution of Arg495 to Trp495 in PODXL/mutation/sometimes referred to as the whole mutant complex |

| PODXLWT–Ezrin | Wild-type complex |

| PODXLR495W–Ezrin | Mutant complex |

| PODXLMT–Ezrin | Mutant complex |

| MD Simulations | Molecular dynamics simulations |

| RMSD | Root mean square deviation |

| RMSF | Root mean square fluctuation |

| Rg | Radius of gyration |

| CoM | Centre of mass |

| THC | Tetrahydrocannabinol |

References

- Kershaw, D.B.; Wiggins, J.E.; Wharram, B.L.; Wiggins, R.C. Assignment of the Human Podocalyxin-like Protein (PODXL) Gene to 7q32-Q33. Genomics 1997, 45, 239–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhaman, S.; Prasad, K.; Behari, M.; Muthane, U.B.; Juyal, R.C.; Thelma, B.K. Discovery of a Frameshift Mutation in Podocalyxinlike (PODXL) Gene, Coding for a Neural Adhesion Molecule, as Causal for Autosomal-Recessive Juvenile Parkinsonism. J. Med. Genet. 2016, 53, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Tran, N.; Wang, Y.; Nie, G. Podocalyxin in Normal Tissue and Epithelial Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.S.; McNagny, K.M. The Role of Podocalyxin in Health and Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 1669–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, R.A.; Takeda, T.; Zak, B.; Schmieder, S.; Benoit, V.M.; McQuistan, T.; Furthmayr, H.; Farquhar, M.G. The Glomerular Epithelial Cell Anti-Adhesin Podocalyxin Associates with the Actin Cytoskeleton through Interactions with Ezrin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2001, 12, 1589–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, D.M.; Roignot, J.; Datta, A.; Overeem, A.W.; Kim, M.; Yu, W.; Peng, X.; Eastburn, D.J.; Ewald, A.J.; Werb, Z.; et al. A Molecular Switch for the Orientation of Epithelial Cell Polarization. Dev. Cell 2014, 31, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T.; McQuistan, T.; Orlando, R.A.; Farquhar, M.G. Loss of Glomerular Foot Processes Is Associated with Uncoupling of Podocalyxin from the Actin Cytoskeleton. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 108, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmieder, S.; Nagai, M.; Orlando, R.A.; Takeda, T.; Farquhar, M.G. Podocalyxin Activates RhoA and Induces Actin Reorganization through NHERF1 and Ezrin in MDCK Cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 2289–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröse, J.; Chen, M.B.; Hebron, K.E.; Reinhardt, F.; Hajal, C.; Zijlstra, A.; Kamm, R.D.; Weinberg, R.A. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Induces Podocalyxin to Promote Extravasation via Ezrin Signaling. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 962–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Library of Medicine (US), N.C. for B. I. EZR Ezrin Gene NCBI. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/7430 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Takahashi, K.; Sasaki, T.; Mammoto, A.; Takaishi, K.; Kameyama, T.; Tsukita, S.; Tsukita, S.; Takai, Y. Direct Interaction of the Rho GDP Dissociation Inhibitor with Ezrin/Radixin/Moesin Initiates the Activation of the Rho Small G Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 23371–23375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujuguet, P.; Del Maestro, L.; Gautreau, A.; Louvard, D.; Arpin, M. Ezrin Regulates E-Cadherin-Dependent Adherens Junction Assembly through Rac1 Activation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003, 14, 2181–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.W.; Sun, M.S.; Liao, M.Y.; Chung, C.H.; Chi, Y.H.; Chiou, L.T.; Yu, J.; Lou, K.L.; Wu, H.C. Podocalyxin-like 1 Promotes Invadopodia Formation and Metastasis through Activation of Rac1/Cdc42/Cortactin Signaling in Breast Cancer Cells. Carcinogenesis 2014, 35, 2425–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, C.; Wan, X.; Bose, S.; Cassaday, R.; Olomu, O.; Mendoza, A.; Yeung, C.; Gorlick, R.; Hewitt, S.M.; Helman, L.J. The Membrane-Cytoskeleton Linker Ezrin Is Necessary for Osteosarcoma Metastasis. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautreau, A.; Poullet, P.; Louvard, D.; Arpin, M. Ezrin, a Plasma Membrane-Microfilament Linker, Signals Cell Survival through the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt Pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 7300–7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román-Fernández, A.; Mansour, M.A.; Kugeratski, F.G.; Anand, J.; Sandilands, E.; Galbraith, L.; Rakovic, K.; Freckmann, E.C.; Cumming, E.M.; Park, J.; et al. Spatial Regulation of the Glycocalyx Component Podocalyxin Is a Switch for Prometastatic Function. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eabq1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondka, Z.; Dhir, N.B.; Carvalho-Silva, D.; Jupe, S.; Madhumita; McLaren, K.; Starkey, M.; Ward, S.; Wilding, J.; Ahmed, M.; et al. COSMIC: A Curated Database of Somatic Variants and Clinical Data for Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1210–D1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.G.; Lee, M.; Lee, K.B.; Hughes, M.; Kwon, B.S.; Lee, S.; McNagny, K.M.; Ahn, Y.H.; Ko, J.M.; Ha, I.S.; et al. Loss of Podocalyxin Causes a Novel Syndromic Type of Congenital Nephrotic Syndrome. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017, 49, e414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Aznar, J.; Besada-Cerecedo, M.; Castro-Alonso, C.; Sierra Carpio, M.; Blasco, M.; Quiroga, B.; Červienka, M.; Mouzo, R.; Torra, R.; Ortiz, A.; et al. Novel Truncating Variants in PODXL Represent a New Entity to Be Explored Among Podocytopathies. Genes 2025, 16, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.H.; Lin, W.L.; Hou, Y.T.; Pu, Y.S.; Shun, C.T.; Chen, C.L.; Wu, Y.Y.; Chen, J.Y.; Chen, T.H.; Jou, T.S. Podocalyxin EBP50 Ezrin Molecular Complex Enhances the Metastatic Potential of Renal Cell Carcinoma through Recruiting Rac1 Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor ARHGEF7. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 176, 3050–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honorato, R.V.; Trellet, M.E.; Jiménez-García, B.; Schaarschmidt, J.J.; Giulini, M.; Reys, V.; Koukos, P.I.; Rodrigues, J.P.G.L.M.; Karaca, E.; van Zundert, G.C.P.; et al. The HADDOCK2.4 web server: A leap forward in integrative modelling of biomolecular complexes. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 3219–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, C.; Boelens, R.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J. HADDOCK: A Protein-Protein Docking Approach Based on Biochemical or Biophysical Information. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 1731–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Chen, C.; Lei, X.; Zhao, J.; Liang, J. CASTp 3.0: Computed Atlas of Surface Topography of Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W363–W367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastman, P.; Galvelis, R.; Peláez, R.P.; Abreu, C.R.A.; Farr, S.E.; Gallicchio, E.; Gorenko, A.; Henry, M.M.; Hu, F.; Huang, J.; et al. OpenMM 8: Molecular Dynamics Simulation with Machine Learning Potentials. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindah, E. Gromacs: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A Web-Based Graphical User Interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.R.; Brooks, C.L.; Mackerell, A.D.; Nilsson, L.; Petrella, R.J.; Roux, B.; Won, Y.; Archontis, G.; Bartels, C.; Boresch, S.; et al. CHARMM: The Biomolecular Simulation Program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 1545–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Cheng, X.; Swails, J.M.; Yeom, M.S.; Eastman, P.K.; Lemkul, J.A.; Wei, S.; Buckner, J.; Jeong, J.C.; Qi, Y.; et al. CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM Simulations Using the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 3.0; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar]

- Lutimba, S.; Saleem, B.; Aleem, E.; Mansour, M.A. In Silico Analysis of Triamterene as a Potential Dual Inhibitor of VEGFR-2 and c-Met Receptors. J. Xenobiot. 2024, 14, 1962–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanner, M.F. Python: A Programming Language for Software Integration and Development. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 1999, 17, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, M.; Bertoni, D.; Magana, P.; Paramval, U.; Pidruchna, I.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Tsenkov, M.; Nair, S.; Mirdita, M.; Yeo, J.; et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database in 2024: Providing Structure Coverage for over 214 Million Protein Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D368–D375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varadi, M.; Anyango, S.; Deshpande, M.; Nair, S.; Natassia, C.; Yordanova, G.; Yuan, D.; Stroe, O.; Wood, G.; Laydon, A.; et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: Massively Expanding the Structural Coverage of Protein-Sequence Space with High-Accuracy Models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D439–D444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.J.; Nassar, N.; Bretscher, A.; Cerione, R.A.; Karplus, P.A. Structure of the Active N-Terminal Domain of Ezrin: Conformational and Mobility Changes Identify Keystone Interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 4949–4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgdebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D609–D617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Qi, S.; Hu, W.; Fang, Z.; Yu, D.; Liu, T.; Wu, J.; Wu, Y.; Wu, A.; Feng, L.; et al. Integrative Analysis Reveals Clinically Relevant Molecular Fingerprints in Pancreatic Cancer. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 26, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, D.; Horrillo, A.; Alquezar, C.; González-Manchón, C.; Parrilla, R.; Ayuso, M.S. Control of Cell Adhesion and Migration by Podocalyxin. Implication of Rac1 and Cdc42. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 432, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, J.M.; Harrop, S.J.; Duff, A.P.; Sokolova, A.V.; Crossett, B.; Walsh, J.C.; Beckham, S.A.; Nguyen, C.D.; Davies, R.B.; Glöckner, C.; et al. Structural Characterization Suggests Models for Monomeric and Dimeric Forms of Full-Length Ezrin. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 2763–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barret, C.; Roy, C.; Montcourrier, P.; Mangeat, P.; Niggli, V. Mutagenesis of the Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-Bisphosphate (PIP2) Binding Site in the NH2-Terminal Domain of Ezrin Correlates with Its Altered Cellular Distribution. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 151, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saponaro, A.; Maione, V.; Bonvin, A.; Cantini, F. Understanding Docking Complexes of Macromolecules Using HADDOCK: The Synergy between Experimental Data and Computations. Bio Protoc. 2020, 10, e3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R.A.; Rullmann, J.A.C.; MacArthur, M.W.; Kaptein, R.; Thornton, J.M. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: Programs for Checking the Quality of Protein Structures Solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 1996, 8, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R.A.; MacArthur, M.W.; Moss, D.S.; Thornton, J.M. PROCHECK: A Program to Check the Stereochemical Quality of Protein Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993, 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, G.N.; Ramakrishnan, C.; Sasisekharan, V. Stereochemistry of Polypeptide Chain Configurations. J. Mol. Biol. 1963, 7, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, P.; Nilsson, L. Structure and Dynamics of the TIP3P, SPC, and SPC/E Water Models at 298 K. J. Phys, Chem. A 2001, 105, 9954–9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Rauscher, S.; Nawrocki, G.; Ran, T.; Feig, M.; De Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H.; MacKerell, A.D. CHARMM36m: An Improved Force Field for Folded and Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Nat. Methods 2016, 14, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yo, B.; et al. PubChem 2025 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1515–D1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open Babel: An Open Chemical Toolbox. J. Cheminform. 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Goodsell, D.S.; Halliday, R.S.; Huey, R.; Hart, W.E.; Belew, R.K.; Olson, A.J. Automated Docking Using a Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm and an Empirical Binding Free Energy Function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 1639–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 3, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, P.; Zurzu, M.; Paic, V.; Bratucu, M.; Garofil, D.; Tigora, A.; Georgescu, V.; Prunoiu, V.; Pasnicu, C.; Popa, F.; et al. CD34—Structure, Functions and Relationship with Cancer Stem Cells. Medicina 2023, 59, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gary, R.; Bretscher, A. Ezrin Self-Association Involves Binding of an N-Terminal Domain to a Normally Masked C-Terminal Domain That Includes the F-Actin Binding Site. Mol. Biol. Cell 1995, 6, 1061–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fievet, B.T.; Gautreau, A.; Roy, C.; Del Maestro, L.; Mangeat, P.; Louvard, D.; Arpin, M. Phosphoinositide Binding and Phosphorylation Act Sequentially in the Activation Mechanism of Ezrin. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 164, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhou, R.; Mettler, S.; Wu, T.; Abbas, A.; Delaney, J.; Forte, J.G. High Turnover of Ezrin T567 Phosphorylation: Conformation, Activity, and Cellular Function. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007, 293, C874–C884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carugo, O.; Djinovic Carugo, K. Half a Century of Ramachandran Plots. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2013, 6, 1333–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Jin, W.W.; Tsuji, K.; Chen, Y.; Nomura, N.; Su, L.; Yui, N.; Arthur, J.; Cotecchia, S.; Păunescu, T.G.; et al. Ezrin Directly Interacts with AQP2 and Promotes Its Endocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 2914–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Guo, Z.; Wang, F.; Fu, L. KRAS Mutation: From Undruggable to Druggable in Cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricelli, M.P.; Janes, M.R.; Li, L.S.; Hansen, R.; Peters, U.; Kessler, L.V.; Chen, Y.; Kucharski, J.M.; Feng, J.; Ely, T.; et al. Selective Inhibition of Oncogenic KRAS Output with Small Molecules Targeting the Inactive State. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and Computational Approaches to Estimate Solubility and Permeability in Drug Discovery and Development Settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1997, 46, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, G.; Hong, S.H.; Chen, K.; Beauchamp, E.M.; Rahim, S.; Kosturko, G.W.; Glasgow, E.; Dakshanamurthy, S.; Lee, H.S.; Daar, I.; et al. Small Molecule Inhibitors of Ezrin Inhibit the Invasive Phenotype of Osteosarcoma Cells. Oncogene 2012, 31, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.G.; Ruiz-Llorente, L.; Sánchez, A.M.; Díaz-Laviada, I. Activation of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/PKB Pathway by CB1 and CB2 Cannabinoid Receptors Expressed in Prostate PC-3 Cells. Involvement in Raf-1 Stimulation and NGF Induction. Cell Signal. 2003, 15, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.Y.; Shivanne Gowda, S.G.; Lee, S.-G.; Seithi, G.; Ahn, K.S. Cannabidiol Induces ERK Activation and ROS Production to Promote Autophagy and Ferroptosis in Glioblastoma Cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 394, 110995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grotenhermen, F. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2003, 42, 327–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Collet, J.; Shapiro, S.; Ware, M.A. Adverse effects of medical cannabinoids: A systematic review. CMAJ 2008, 178, 1669–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huestis, M.A. Human Cannabinoid Pharmacokinetics. Chem. Biodivers. 2007, 4, 1770–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, S.R.D.; Leary, A. Lapatinib: A Novel EGFR/HER2 Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor for Cancer. Drugs Today 2006, 42, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Yu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, F.; Yu, Z. The Effectiveness of Lapatinib in HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients Pretreated with Multiline Anti-HER2 Treatment: A Retrospective Study in China. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 20, 15330338211037812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tool | Version | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| HADDOCK | 2.4 | Protein–protein docking |

| CASTp | 3.0 | Identification/Analysis of surface binding sites |

| UCSF Chimera | 1.18 | Mutagenesis, visualisation tasks |

| OpenMM | 8.1 | Analysis toolkit and simulations |

| GROMACS | 2024.2 | Analysis toolkit and simulations |

| CHARMM-GUI | 3.7 | Input generation for MD simulation tools like OpenMM and GROMACS |

| PyMOL | 2.5 | Visualisation and analysis of molecular structures |

| VMD | 2.0.0 | Visualisation and analysis of molecular structures |

| MoLuDock viewer | 1.0 | Visualisation and analysis of molecular structures |

| AutoDock | 4.2.6 | Ligand docking |

| MGLTools | 1.5.4 | Input file preparation |

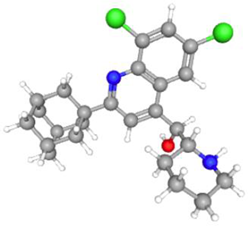

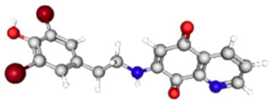

| Common Name | IUPAC Name | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Canonical SMILES | 3D Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lapatinib | N-(3-chloro-4-((3-fluorophenyl)methoxy)phenyl)-6-(5-((2-methylsulfonylethylamino)methyl)furan-2-yl)quinazolin-4-amine | 581.1 | CS(=O)(=O)CCNCC1=CC=C(O1)C2=CC3=C(C=C2)N=CN=C3NC4=CC(=C(C=C4)OCC5=CC(=CC=C5)F)Cl |  |

| Chrysin | 5,7-dihydroxy-2-phenylchromen-4-one | 254.24 | C1=CC=C(C=C1)C2=CC(=O)C3=C(C=C(C=C3O2)O)O |  |

| Cannabidiol | 2-((1R,6R)-3-methyl-6-prop-1-en-2-ylcyclohex-2-en-1-yl)-5-pentylbenzene-1,3-diol | 314.5 | CCCCCC1=CC(=C(C(=C1)O)(C@@H)2C=C(CC(C@H)2C(=C)C)C)O |  |

| Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) | (6aR,10aR)-6,6,9-trimethyl-3-pentyl-6a,7,8,10a-tetrahydrobenzo(c)chromen-1-ol | 314.5 | CCCCCC1=CC(=C2(C@@H)3C=C(CC(C@H)3C(OC2=C1)(C)C)C)O |  |

| NSC305787 | (2-(1-adamantyl)-6,8-dichloroquinolin-4-yl)-piperidin-2-ylmethanol | 445.4 | C1CCNC(C1)C(C2=CC(=NC3=C2C=C(C=C3Cl)Cl)C45CC6CC(C4)CC(C6)C5)O |  |

| NSC668394 | 7-(2-(3,5-dibromo-4-hydroxyphenyl)ethylamino)quinoline-5,8-dione | 452.1 | C1=CC2=C(C(=O)C(=CC2=O)NCCC3=CC(=C(C(=C3)Br)O)Br)N=C1 |  |

| Candidate Drugs | Binding Affinity in PODXLWT–Ezrin Complex (kcal/mol) | Binding Affinity in PODXLR495W–Ezrin Complex (kcal/mol) | Difference in Binding Affinity Between PODXLR495W–Ezrin and PODXLWT–Ezrin (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lapatinib | −8.538 | −8.744 | +2.41 |

| Chrysin | −7.348 | −7.638 | +3.94 |

| Cannabidiol | −7.260 | −6.425 | −11.50 |

| Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) | −7.437 | −7.157 | −3.76 |

| NSC305787 | −8.207 | −8.612 | +4.93 |

| NSC668394 | −7.775 | −7.101 | −8.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Milutinovic, M.; Lutimba, S.; Mansour, M.A. Structural and Dynamic Insights into Podocalyxin–Ezrin Interaction as a Target in Cancer Progression. J. Xenobiot. 2026, 16, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010025

Milutinovic M, Lutimba S, Mansour MA. Structural and Dynamic Insights into Podocalyxin–Ezrin Interaction as a Target in Cancer Progression. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2026; 16(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilutinovic, Mila, Stuart Lutimba, and Mohammed A. Mansour. 2026. "Structural and Dynamic Insights into Podocalyxin–Ezrin Interaction as a Target in Cancer Progression" Journal of Xenobiotics 16, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010025

APA StyleMilutinovic, M., Lutimba, S., & Mansour, M. A. (2026). Structural and Dynamic Insights into Podocalyxin–Ezrin Interaction as a Target in Cancer Progression. Journal of Xenobiotics, 16(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010025