Comparative Hepatic Toxicity of Pesticides in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, 1758): An Integrated Histopathological, Histochemical, and Enzymatic Biomarker Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Fish

2.2. Experimental Pesticides

2.2.1. Pirimiphos-Methyl

2.2.2. Propamocarb Hydrochloride

2.2.3. 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid

2.3. Experimental Exposure

2.4. Histopathological Assessment

2.5. Histochemical Assessment

2.6. Biochemical Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Histopathological Assessment

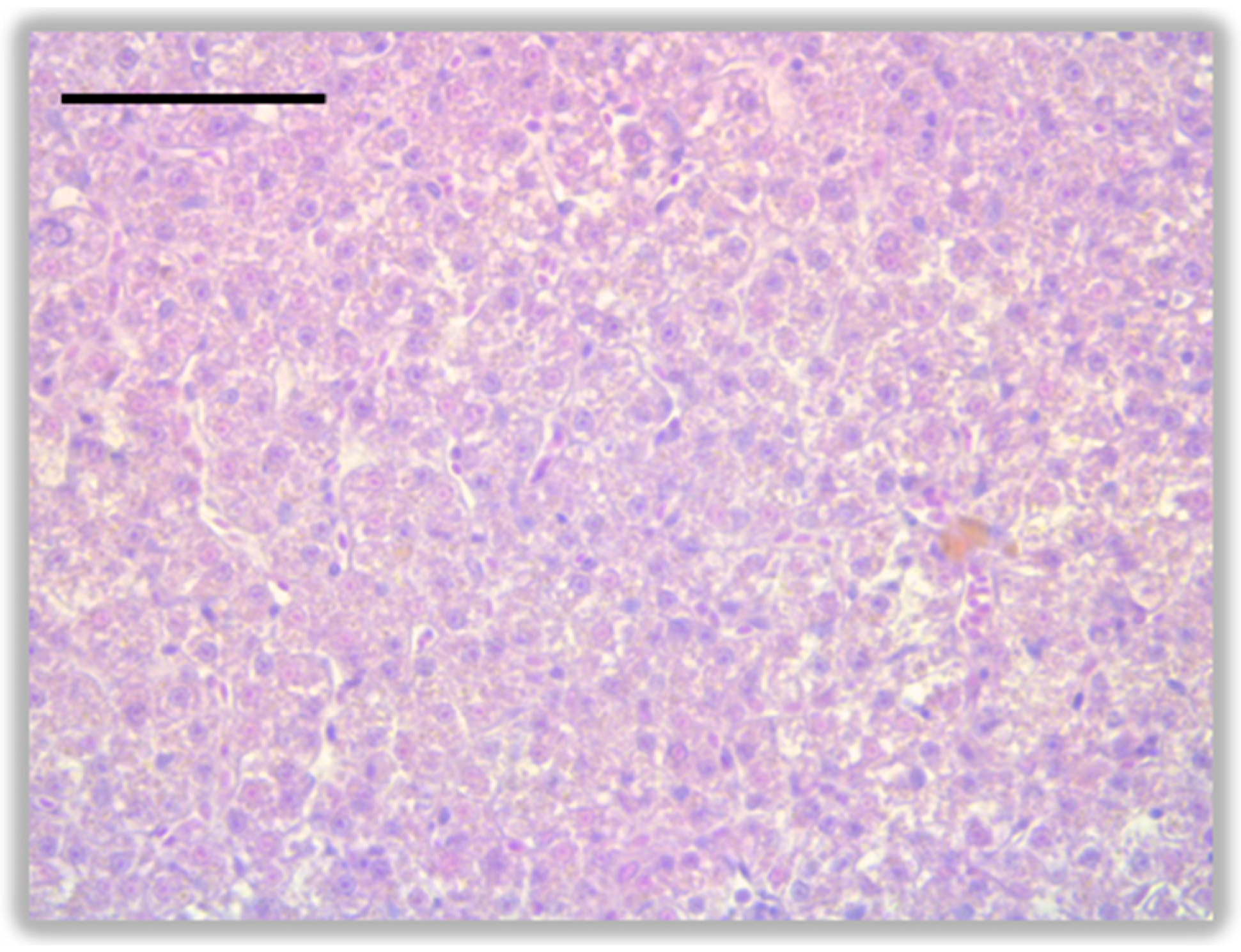

3.1.1. Control Group

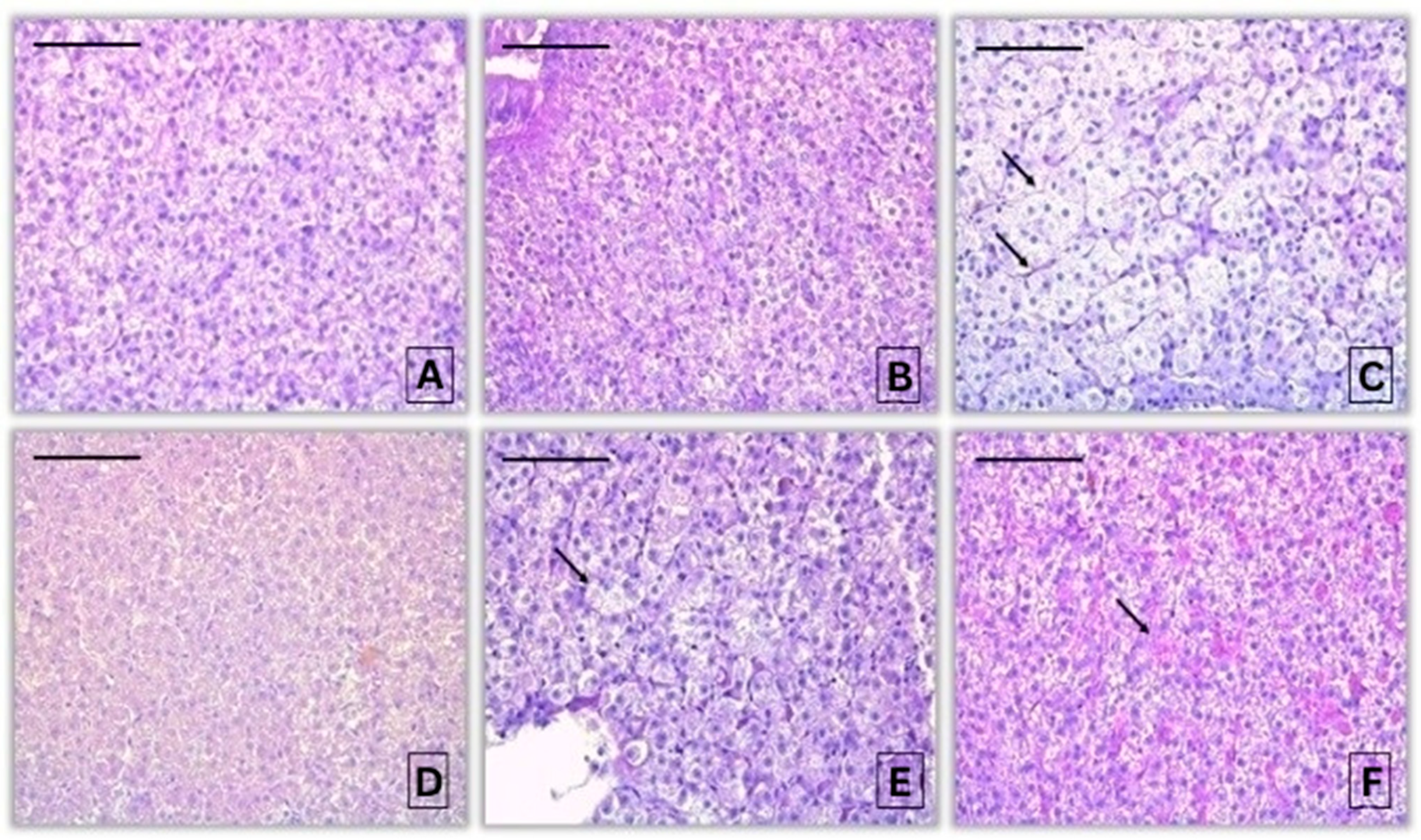

3.1.2. Histopathological Alterations in the Liver of Common Carp After Acute Exposure to Pirimiphos-Methyl

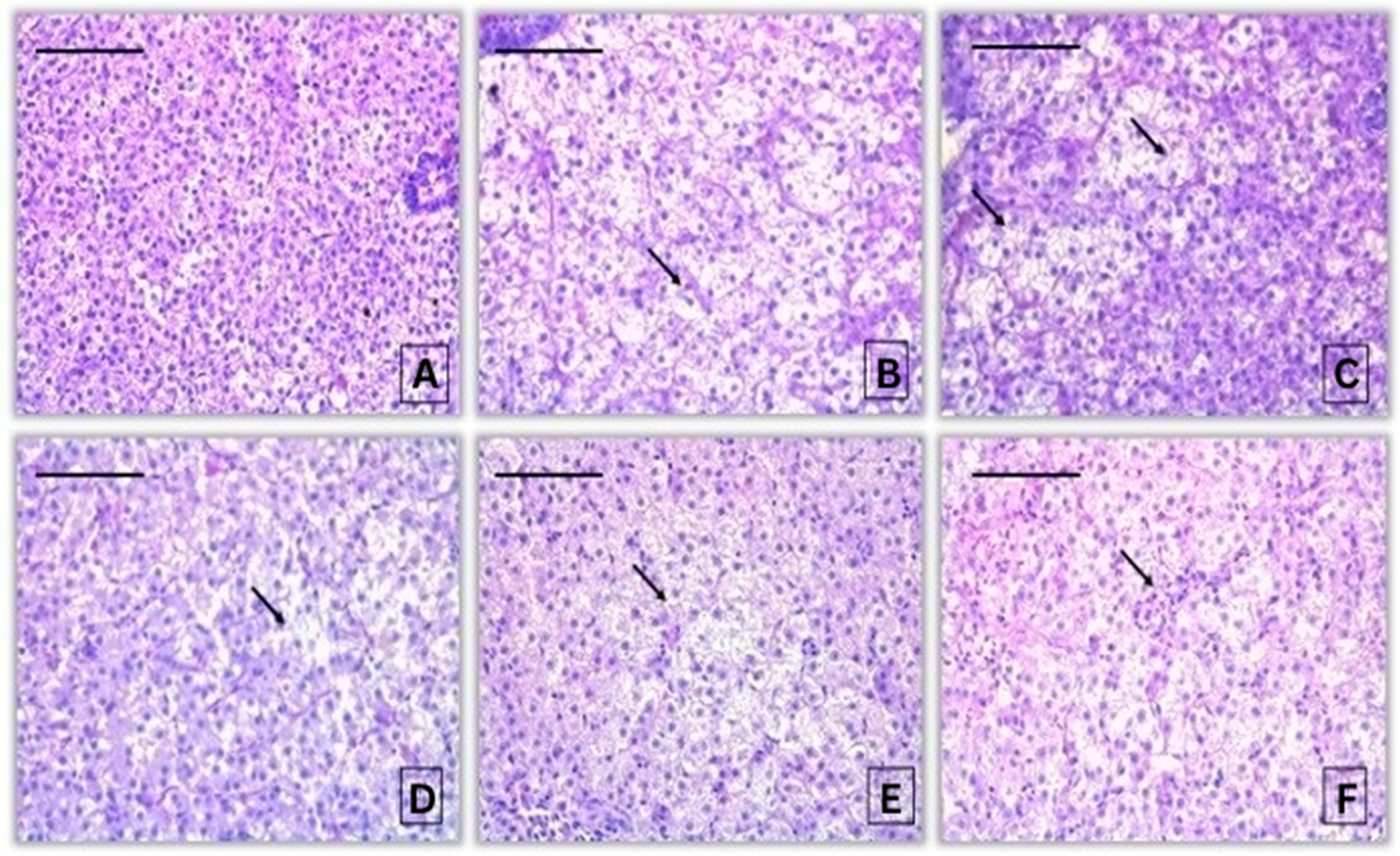

3.1.3. Histopathological Alterations in the Liver of Common Carp After Acute Exposure to Propamocarb Hydrochloride

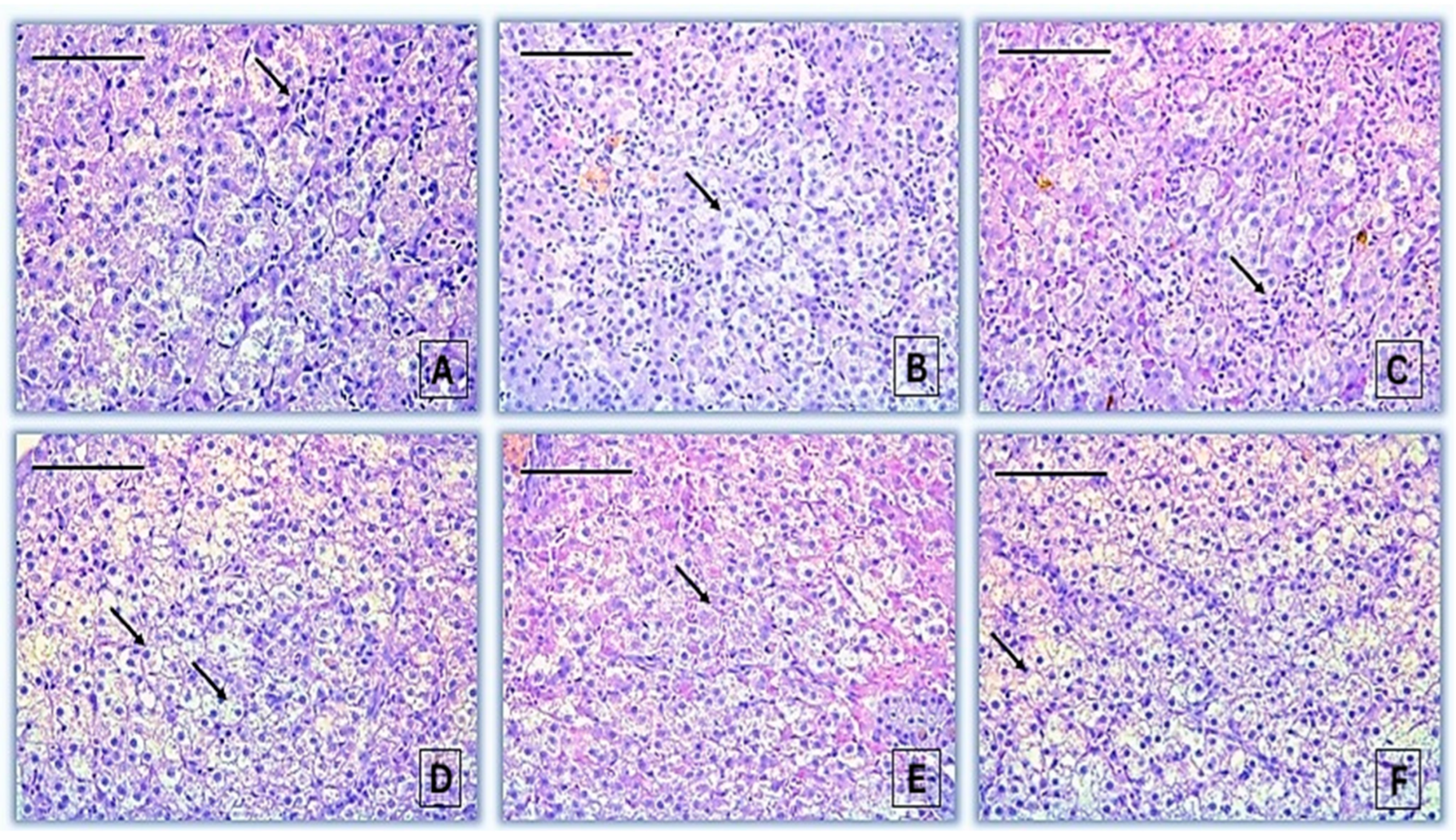

3.1.4. Histopathological Alterations in the Liver of Common Carp After Acute Exposure to 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid

3.2. Histochemical Assessment

3.2.1. Histochemical Alterations in the Liver of Common Carp After Acute Exposure to Pirimiphos-Methyl

3.2.2. Histochemical Alterations in the Liver of Common Carp After Acute Exposure to Propamocarb Hydrochloride

3.2.3. Histochemical Alterations in the Liver of Common Carp After Exposure to 2,4-D

3.3. Biochemical Assessment

3.3.1. Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH)

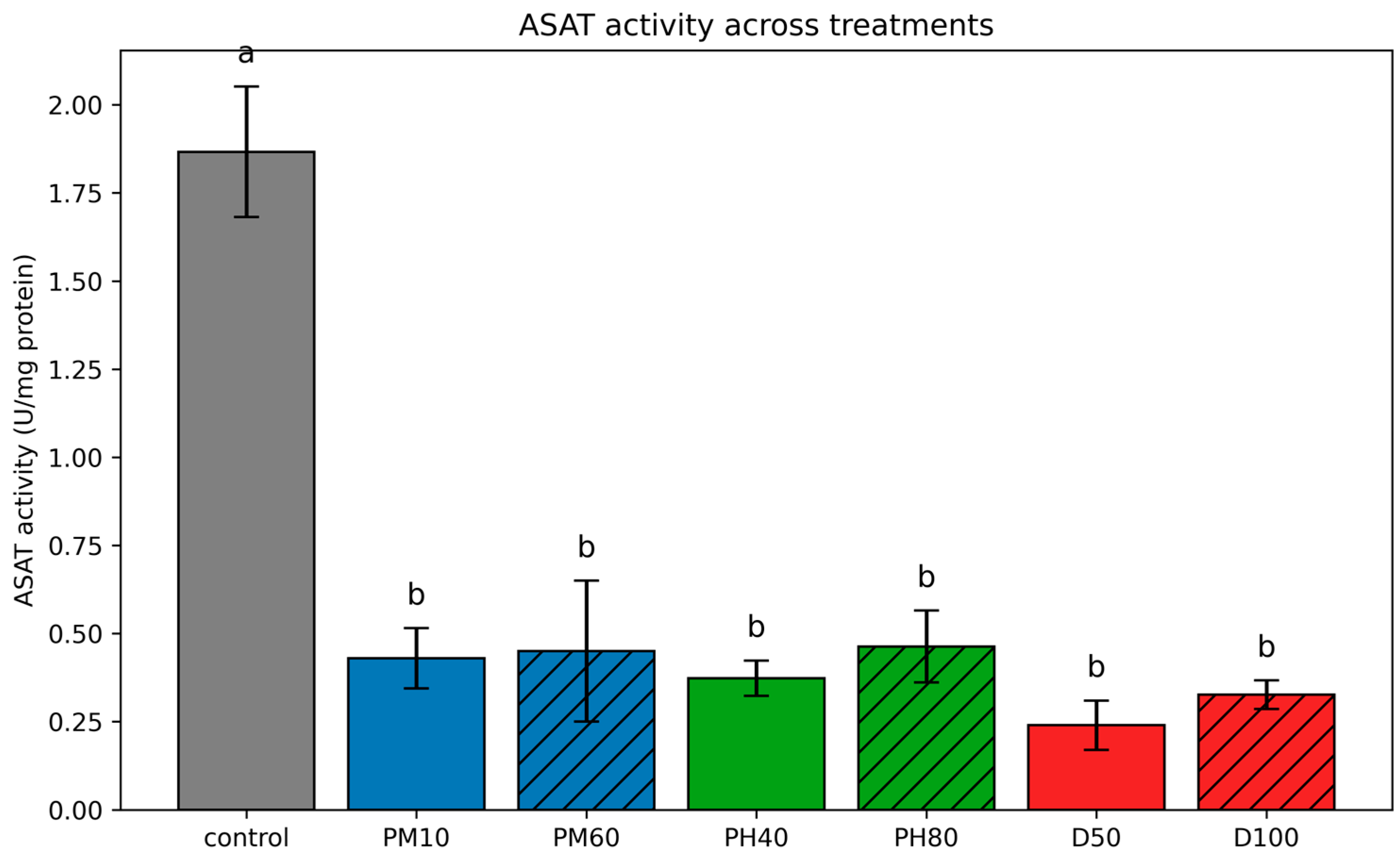

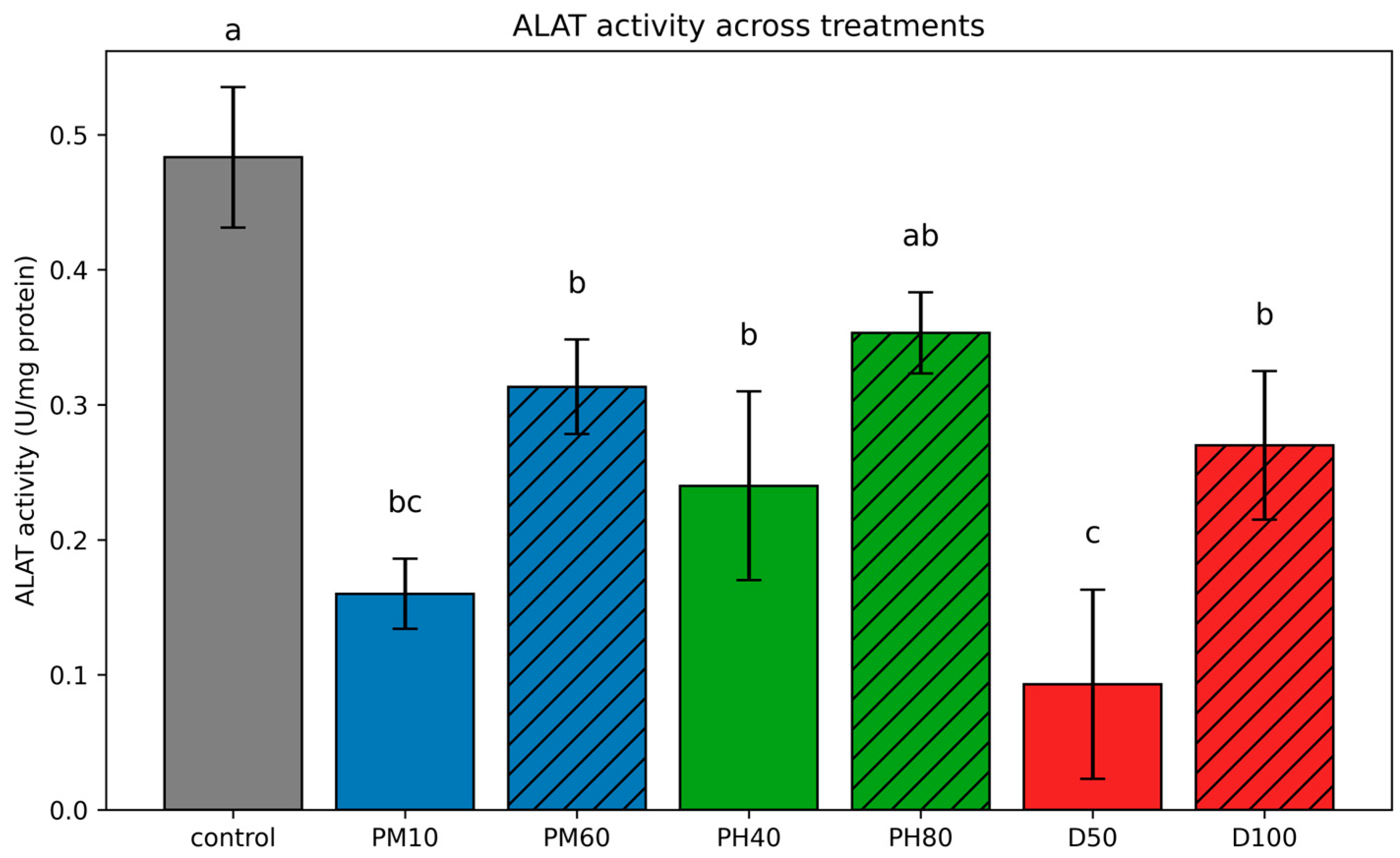

3.3.2. Aspartate Aminotransferase (ASAT) and Alanine Aminotransferase (ALAT)

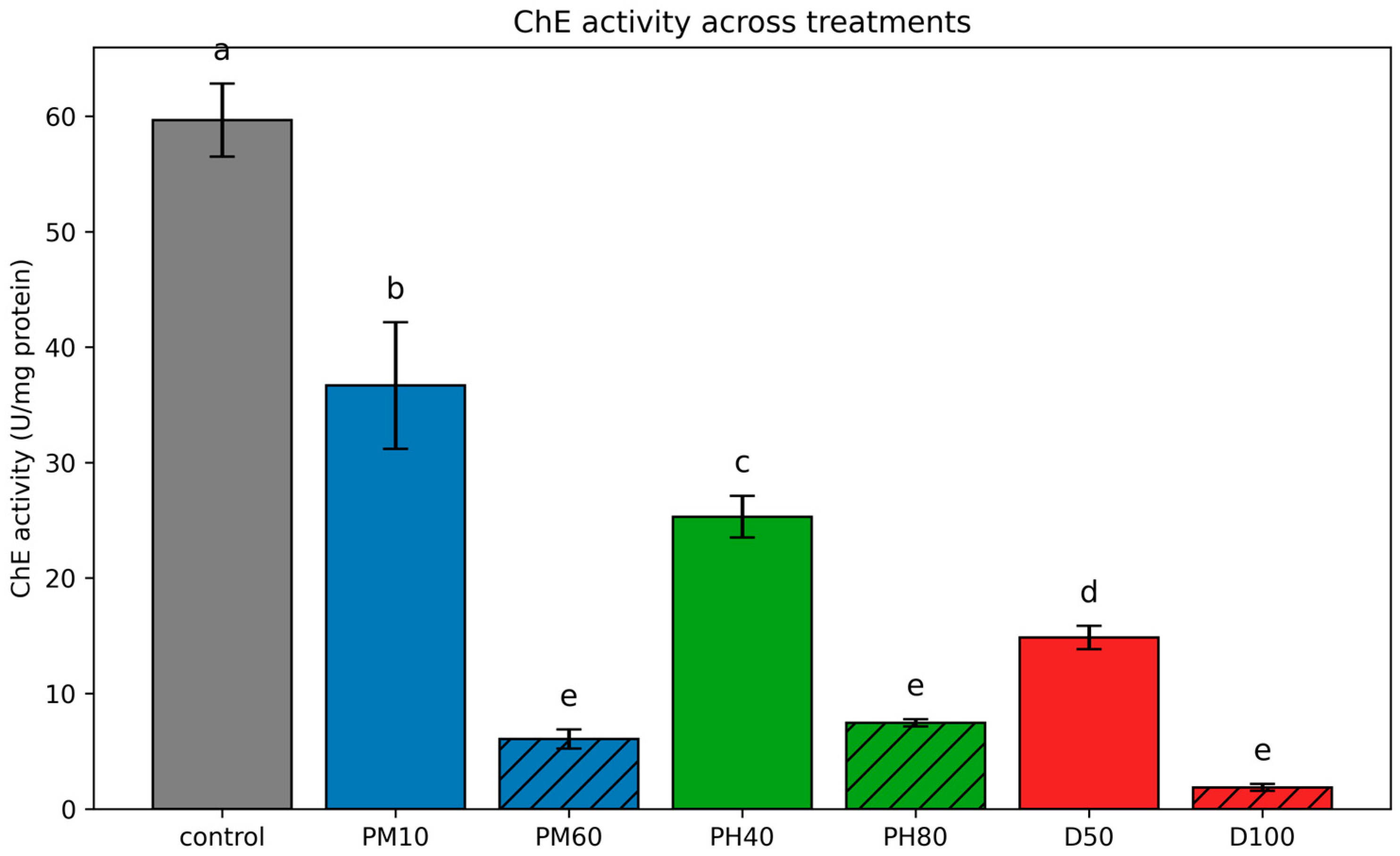

3.3.3. Cholinesterase (ChE)

4. Discussion

4.1. Histopathological Alterations in the Liver of Common Carp After Acute Exposure to the Experimental Pesticides

4.2. Histochemical Alterations in the Liver of Common Carp After Acute Exposure to the Experimental Pesticides

4.3. Biochemical Alterations in the Liver of Common Carp After Exposure to the Experimental Pesticides

4.4. Comparative Effects of Pirimiphos-Methyl, Propamocarb Hydrochloride, and 2,4-D

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sjerps, R.M.A.; Kooij, P.J.F.; van Loon, A.; Van Wezel, A.P. Occurrence of pesticides in Dutch drinking water sources. Chemosphere 2019, 235, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafrudin, M.; Kristanti, R.A.; Yuniarto, A.; Hadibarata, T.; Rhee, J.; Al-Onazi, W.A.; Algarni, T.S.; Almarri, A.H.; Al-Mohaimeed, A.M. Pesticides in Drinking Water-A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Mar Gómez-Ramos, M.; Nannou, C.; Bueno, M.J.M.; Goday, A.; Murcia-Morales, M.; Ferrer, C.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Pesticide residues evaluation of organic crops. A critical appraisal. Food Chem. X 2020, 5, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhl, C.A.; Bakanov, N.; Köthe, S.; Eichler, L.; Sorg, M.; Hörren, T.; Mühlethaler, R.; Meinel, G.; Lehmann, G.U.C. Direct pesticide exposure of insects in nature conservation areas in Germany. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaller, J.G.; Kruse-Plaß, M.; Schlechtriemen, U.; Gruber, E.; Peer, M.; Nadeem, I.; Formayer, H.; Hutter, H.-P.; Landler, L. Pesticides in ambient air, influenced by surrounding land use and weather, pose a potential threat to biodiversity and humans. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stehle, S.; Schulz, R. Agricultural insecticides threaten surface waters at the global scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5750–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Parada, A.; Goyenola, G.; de Mello, F.T.; Heinzen, H. Recent advances and open questions around pesticide dynamics and effects on freshwater fishes. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 4, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Shahzad, B.; Tanveer, M.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Handa, N.; Kohli, S.K.; Yadav, P.; Bali, A.S.; Parihar, R.D.; et al. Worldwide pesticide usage and its impacts on ecosystem. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S.; Parween, M.; Raju, N.J. Pesticides in the hydrogeo-environment: A review of contaminant prevalence, source and mobilisation in India. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 5481–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babuji, P.; Thirumalaisamy, S.; Duraisamy, K.; Periyasamy, G. Human Health Risks due to Exposure to Water Pollution: A Review. Water 2023, 15, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Moneim, A.M.; Al-Kahtani, M.A.; Elmenshawy, O.M. Histopathological biomarkers in gills and liver of Oreochromis niloticus from polluted wetland environments, Saudi Arabia. Chemosphere 2012, 88, 1028–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza-Bastos, L.R.; Bastos, L.P.; Carneiro, P.C.F.; Guiloski, I.C.; de Assis, H.C.S.; Padial, A.A.; Freire, C.A. Evaluation of the water quality of the upper reaches of the main Southern Brazil river (Iguacu river) through in situ exposure of the native siluriform Rhamdia quelen in cages. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Sutradhar, L.; Sarker, T.R.; Saha, S.; Iqbal, M.M. Toxic effects of chlorpyrifos on the growth, hematology, and different organs histopathology of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 103316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Al Bari, A.; Shimul, S.A.; Al Mazed, M.; Nahid, S.A. Enhancement of body coloration of sword-tail fish (Xiphophorus helleri): Plant-derived bio-resources could be converted into a potential dietary carotenoid supplement. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgieva, E.; Kovacheva, E.; Yancheva, V.; Velcheva, I.; Hrischev, P.; Atanassova, P.; Tomov, S.; Stoyanova, S. Pesticides induce fatty degeneration in liver of Cyprinus carpio (Linnaeus 1758) after acute exposure. Ecol. Balk. 2023, 15, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sachi, I.T.C.; Bonomo, M.M.; Sakuragui, M.M.; Modena, P.Z.; Paulino, M.G.; Carlos, R.M.; Fernandes, J.B.; Fernandes, M.N. Biochemical and morphological biomarker responses in the gills of a Neotropical fish exposed to a new flavonoid metal-insecticide. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanova, S.; Georgieva, E.; Kovacheva, E.; Antal, L.; Somogyi, D.; Uzochukwu, I.E.; Nagy, L.; Nyeste, K.; Yancheva, V. Kidneys Under Siege: Pesticides Impact Renal Health in the Freshwater Fish Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, 1758). Toxics 2025, 13, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, E.; Yancheva, V.; Stoyanova, S.; Velcheva, I.; Iliev, I.; Vasileva, T.; Bivolarski, V.; Petkova, E.; László, B.; Nyeste, K.; et al. Which Is More Toxic? Evaluation of the Short-Term Toxic Effects of Chlorpyrifos and Cypermethrin on Selected Biomarkers in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio, Linnaeus 1758). Toxics 2021, 9, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaninova, A.; Smutna, M.; Modra, H.; Svobodova, Z. A review: Oxidative stress in fish induced by pesticides. Neuro. Endocrinol. Lett. 2009, 30, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, T.; Hudson, M.J.; Uchiyama, J.; Makibayashi, K.; Zhang, J. Common carp aquaculture in Neolithic China dates back 8,000 years. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 1415–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Feng, D.; Huang, J.; Jin, Z.; Ma, F.; Xu, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yu, M.; et al. Effect of exercise intensity on growth performance, serum biochemistry parameters, liver antioxidant capacity, and intestinal health of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) in recirculating aquaculture system. Aquaculture 2025, 595, 741631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Yousafzai, A.M.; Siraj, M.; Ahmad, R.; Ahmad, I.; Nadeem, M.S.; Ahmad, W.; Akbar, N.; Muhammad, K. Pollution Problem in River Kabul: Accumulation Estimates of Heavy Metals in Native Fish Species. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 537368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepic, S.; Hackenberger, B.K.; Velki, M.; Lončarić, Ž.; Hackenberger, D.K. Effects of individual and binary-combined commercial insecticides endosulfan, temephos, malathion and pirimiphos-methyl on biomarker responses in earthworm Eisenia andrei. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2013, 36, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxborough, R.M. Trends in US President’s Malaria Initiative-funded indoor residual spray coverage and insecticide choice in sub-Saharan Africa (2008-2015): Urgent need for affordable, long-lasting insecticides. Malar. J. 2016, 15, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dengela, D.; Seyoum, A.; Lucas, B.; Johns, B.; George, K.; Belemvire, A.; Caranci, A.; Norris, L.C.; Fornadel, C.M. Multi-country assessment of residual bio-efficacy of insecticides used for indoor residual spraying in malaria control on different surface types: Results from program monitoring in 17 PMI/USAID-supported IRS countries. Parasit. Vectors 2018, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakeshott, J.G.; Devonshire, A.L.; Claudianos, C.; Sutherland, T.D.; Horne, I.; Campbell, P.M.; Ollis, D.L.; Russell, R.J. Comparing the organophosphorus and carbamate insecticide resistance mutations in cholin- and carboxyl-esterases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2005, 157–158, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donarski, W.J.; Dumas, D.P.; Heitmeyer, D.P.; Lewis, V.E.; Raushel, F.M. Structure-activity relationships in the hydrolysis of substrates by the phosphotriesterase from Pseudomonas diminuta. Biochemistry 1989, 28, 4650–4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, H.; Balszuweit, F.; Steinritz, D.; Kehe, K.; Worek, F.; Thiermann, H. Toxicokinetic Aspects of Nerve Agents and Vesicants. In Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents, 2nd ed; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 817–856. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroh, E.A.; Krass, W.; Hemmen, C. Propamocarb, einneues Fungizid zur Abwehr von Oomyceten im Zierpflanzen- und Gemüsebau. Meded. Fac. Landbouw. Rijksuniv. Gent. 1978, 43, 933–942. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). Propamocarb Hydrochloride R.E.D. FACTS—Prevention, Pesticides and Toxic Substances (7508W). 1995. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Elliott, M.; Shamoun, S.F.; Sumampong, G. Effects of systemic and contact fungicides on life stages and symptom expression of Phytophthora ramorum in vitro and in planta. Crop Prot. 2015, 67, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.C.; Hird, S.J.; Sykes, M.D.; Startin, J.R. Determination of residues of propamocarb in wine by liquid chromatography-electrospray mass spectrometry with direct injection. Food Addit. Contam. 2004, 21, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra, M.; de Kok, A. Determination of propamocarb in vegetables using polymer-based high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2002, 972, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Alrahman, S.H.; Almaz, M.M. Degradation of propamocarb-hydrochloride in tomatoes, potatoes and cucumber using HPLC-DAD and QuEChERS methodology. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2012, 89, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmuck, G.; Mihail, F. Effects of the carbamates fenoxycarb, propamocarb and propoxur on energy supply, glucose utilization and SH-groups in neurons. Arch. Toxicol. 2004, 78, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Wang, J.; Farooq, M.A.; Khan, M.S.; Xu, L.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, M.; Muños, S.; Li, Q.X.; Zhou, W. Potential impact of the herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid on human and ecosystems. Environ. Int. 2018, 111, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, A.J.A.; Tunega, D.; Haberhauer, G.; Gerzabek, M.H.; Lischka, H. Interaction of the 2.4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid herbicide with soil organic matter moieties: A theoretical study. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2007, 58, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnert, G.K.; Freitas, M.B.; DeQuattro, Z.A.; Barry, T.; Karasov, W.H. Effects of low, subchronic exposure of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and commercial 2,4-D formulations on early life stages of fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 2550–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jazan, E.; Griffin, T.; Woodin, M. Mapping temporal trends of pesticide use and identifying potential non-occupation population exposure using a geospatial approach. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. Insight into the mode of action of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) as an herbicide. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2014, 56, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stackelberg, K. A Systematic Review of Carcinogenic Outcomes and Potential Mechanisms from Exposure to 2,4-D and MCPA in the Environment. J. Toxicol. 2013, 2013, 371610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for Examination of Water and Wastewater, 21st ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseland, B.O.; Rognerud, S.; Collen, P.; Grimalt, J.O.; Vives, I.; Massabuau, J.C.; Lackner, R.; Hofer, R.; Raddum, G.G.; Fjellheim, A.; et al. Brown Trout in Lochnagar: Population and Contamination by Metals and Organic Micropollutants. In Lochnagar: The Natural History of a Mountain Lake; Rose, N.L., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 253–285. [Google Scholar]

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2010, 276, 33–79. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32010L0063 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Romeis, B. Mikroskopische Technik; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=NDOnDwAAQBAJ (accessed on 19 January 2026).

- Bernet, D.; Schmidt, H.; Meier, W.; Burkhardt-Holm, P.; Wahli, T. Histopathology in fish: Proposal for a protocol to assess aquatic pollution. J. Fish Dis. 1999, 22, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, A.; Costa, J.; Serrão, J.; Cruz, C.; Eiras, J.C. A histology-based fish health assessment of farmed seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.). Aquaculture 2015, 448, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerli, S.; Bernet, D.; Burkhardt-Holm, P.; Schmidt-Posthaus, H.; Vonlanthen, P.; Wahli, T.; Segner, H. Assessment of fish health status in four Swiss rivers showing a decline of brown trout catches. Aquat. Sci. 2007, 69, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc, M.J. Histological and histochemical uses of periodic acid. Stain. Technol. 1948, 23, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.K.; Mohanty, B. Acute toxicity impacts of hexavalent chromium on behavior and histopathology of gill, kidney and liver of the freshwater fish, Channa punctatus (Bloch). Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008, 26, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsonova, M.V.; Lapteva, T.I.; Filippovich, I.B. Aminotransferases in early development of salmonid fish. Ontogenez 2005, 36, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Shehawi, A.M.; Ali, F.K.; Seehy, M.A. Estimation of water pollution by genetic biomarkers in tilapia and catfish species shows species-site interaction. Afr. J. Agric. 2013, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pohanka, M. Cholinesterases, a target of pharmacology and toxicology. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Palacky Univ. Olomouc 2011, 155, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimijoin, S.; Koenigsberger, C. Cholinesterases in neural development: New findings and toxicologic implications. Environ. Health Perspect. 1999, 107, 59–64. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Soreq, H.; Seidman, S. Acetylcholinesterase--new roles for an old actor. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 2, 294–302. [Google Scholar]

- Koie, T.; Ohyama, C.; Mikami, J.; Iwamura, H.; Fujita, N.; Sato, T.; Kojima, Y.; Fukushi, K.; Yamamoto, H.; Imai, A.; et al. Preoperative butyrylcholinesterase level as an independent predictor of overall survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients treated with nephrectomy. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 948305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mommsen, T.P. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 in Fishes: The Liver and Beyond1. Am. Zool. 2015, 40, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassault, A. Lactate dehydrogenase. In Methods of Enzymatic Analysis, Enzymes: Oxireductases, Transferases; Bergmeyer, M.O., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Henley, K.S.; Pollard, H.M. A new method for the determination of glutamic oxalacetic and glutamic pyruvic transaminase in plasma. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1955, 46, 785–789. [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewski, F.; Ladue, J.S. Serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase in cardiac with hepatic disease. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1956, 91, 569–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitman, S.; Frankel, S. A colorimetric method for the determination of serum glutamic oxalacetic and glutamic pyruvic transaminases. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1957, 28, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtis, C.A.; Ashwood, E.R. Tietz Text-Book of Clinical Chemistry, 2nd ed.; W.B. Sunders Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Minarik, T.A.; Vick, J.A.; Schultz, M.M.; Bartell, S.E.; Martinovic-Weigelt, D.; Rearick, D.C.; Schoenfuss, H.L. On-Site Exposure to Treated Wastewater Effluent Has Subtle Effects on Male Fathead Minnows and Pronounced Effects on Carp. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2014, 50, 358–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacheva, E.; Georgieva, E.; Velcheva, I.; Nikolova, M.; Atanassova, P.; Todorova, B.; Todorova-Bambaldokova, D.; Yancheva, V.; Stoyanova, S.; Tomov, S. Acute Histopathological Changes in Common carp (Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, 1785) Gills: Pirimiphos-methyl, 2, 4—Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid and Propamocarb Hydrochloride Effects. Ecol. Balk. 2022, 14, 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammod Mostakim, G.; Zahangir, M.; Mishu, M.M.; Rahman, K.; Islam, M.S. Alteration of Blood Parameters and Histoarchitecture of Liver and Kidney of Silver Barb after Chronic Exposure to Quinalphos. J. Toxicol. 2015, 2015, 415984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, B.; Vakita, V.R. Histopathological Changes In The Gill And Liver Of Freshwater Fish Labeo Rohita (Hamilton) Exposed To Novaluron. Innoriginal Int. J. Sci. 2014, 1, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Babatunde, M.; Oladimeji, A.A.; Rafindadi, A. Histopathological Changes in the Gills, Livers and Brains of O. niloticus (TREWAVAS) Exposed to Paraquat in Chronic Bioassay. Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Emadi, H.; Shariatzadeh, S.; Jamili, S.; Mashinchian, A. Evaluation of toxicity and biochemical effects of the Oxadiargyl in Common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Int. J. Aquat. Biol. 2018, 6, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ladipo, M.; Doherty, F.; Oyebadejo, S. Acute Toxicity, Behavioural Changes and Histopathological Effect of Paraquat Dichloride on Tissues of Catfish (Clarias gariepinus). Int. J. Biol. 2011, 3, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, F.; Hofer, R. The effects of treated domestic sewage on three organs (gills, kidney, liver) of brown trout (Salmo trutta). Water Res. 1993, 27, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.M.; Ham, K.D.; Greely, M.S.; LeHew, R.F.; Hinton, D.E.; Saylor, C.F. Downstream gradients in bioindicator responses: Point source contaminant effects on fish health. Can. J. Fish Aquat. Sci. 1996, 53, 2177–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaiger, J.; Wanke, R.; Adam, S.; Pawert, M.; Honnen, W.; Triebskorn, R. The use of histopathological indicators to evaluate contaminant-related stress in fish. J. Aquat. Ecosyst. Stress Recovery 1997, 6, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernet, D.; Schmidt-Posthaus, H.; Wahli, T.; Burkhardt-Holm, P. Evaluation of Two Monitoring Approaches to Assess Effects of Waste Water Disposal on Histological Alterations in Fish. Hydrobiologia 2004, 524, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agamy, E. Histopathological liver alterations in juvenile rabbit fish (Siganus canaliculatus) exposed to light Arabian crude oil, dispersed oil and dispersant. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2012, 75, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Bridle, A.; Leef, M.; Gagnon, M.M.; Hassell, K.L.; Nowak, B.F. Using a multi-biomarker approach to assess the effects of pollution on sand flathead (Platycephalus bassensis) from Port Phillip Bay, Victoria, Australia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guardiola, F.A.; Cuesta, A.; Meseguer, J.; Martínez, S.; Martínez-Sánchez, M.; Pérez-Sirvent, C.; Esteban, M. Accumulation, histopathology and immunotoxicological effects of waterborne cadmium on gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata). Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2013, 35, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanova, S.; Yancheva, V.; Iliev, I.; Vasileva, T.; Bivolarski, V.; Velcheva, I.; Georgieva, E. Glyphosate induces morphological and enzymatic changes in common carp (Cyprinus carpio L) liver. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 21, 409. [Google Scholar]

- Sigamani, D. Effect of herbicides on fish and histological evaluation. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2015, 1, 437–440. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence Ikechukwu, E.; Ogbomida, E. Histopathological Effects of Gammalin 20 on African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus). Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2010, 2010, 138019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Otaibi, A.M.; Al-Balawi, H.F.A.; Ahmad, Z.; Suliman, E.M. Toxicity bioassay and sub-lethal effects of diazinon on blood profile and histology of liver, gills and kidney of catfish, Clarias gariepinus. Braz. J. Biol. 2019, 79, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawa, V.; Kondal, J.K.; Hundal, S.S.; Kaur, H. Biochemical and Histological Effects of Glyphosate on the Liver of Cyprinus carpio (Linn.). Am. J. Life Sci. 2017, 5, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffar, A.; Hussain, R.; Abbas, G.; Kalim, M.; Khan, A.; Ferrando, S.; Gallus, L.; Ahmed, Z. Fipronil (Phenylpyrazole) induces hemato-biochemical, histological and genetic damage at low doses in common carp, Cyprinus carpio (Linnaeus, 1758). Ecotoxicology 2018, 27, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connett, R.; Sahlin, K. Control of Glycolysis and Glycogen Metabolism. Compr. Physiol. 2011, 4S29, 870–911. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, B.B.; Stanford, G.G.; Ziegler, M.G.; Lake, C.R.; Chernow, B.A.R.T. Catecholamines: Study of interspecies variation. Crit. Care Med. 1989, 17, 1203–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, J.H.; Cerra, F.B.; Coleman, B.; Giovannini, I.; Shetye, M.; Border, J.R.; McMenamy, R.H. Physiological and metabolic correlations in human sepsis. Invited commentary. Surgery 1979, 86, 163–193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chiasson, J.L.; Aylward, J.H.; Shikama, H.; Exton, J.H. Hormonal regulation of glycogen synthase phosphorylation in perfused rat skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1981, 127, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frayn, K.N.; Little, R.; Maycock, P.; Stoner, H. The relationship of plasma catecholamines to acute metabolic and hormonal responses to injury in man. Circ. Shock. 1985, 16, 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Little, R.A.; Frayn, K.N.; Randall, P.E.; Stoner, H.B.; Maycock, P.F. Plasma catecholamine concentrations in acute states of stress and trauma. Arch. Emerg. Med. 1985, 2, 46–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hunt, D.G.; Ivy, J.L. Epinephrine inhibits insulin-stimulated muscle glucose transport. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 93, 1638–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavson, S.M.; Chu, C.A.; Nishizawa, M.; Farmer, B.; Neal, D.; Yang, Y.; Vaughan, S.; Donahue, E.P.; Flakoll, P.; Cherrington, A.D. Glucagon’s actions are modified by the combination of epinephrine and gluconeogenic precursor infusion. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 285, E534–E544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami-Mohajeri, S.; Abdollahi, M. Toxic influence of organophosphate, carbamate, and organochlorine pesticides on cellular metabolism of lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates: A systematic review. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2011, 30, 1119–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matschinsky, F.M.; Ellerman, J.; Krzanowski, J.; Kotler-Brajtburg, J.; Fertel, R. Quantitative histochemistry of glucose metabolism in the islets of Langerhans. Curr. Probl. Clin. Biochem. 1971, 3, 143–182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koundinya, P.R.; Ramamurthi, R. Effect of organophosphate pesticide Sumithion (Fenitrothion) on some aspects of carbohydrate metabolism in a freshwater fish, Sarotherodon (Tilapia) mossambicus (Peters). Experientia 1979, 35, 1632–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, J.G.; Lee, M.J. Soman-induced convulsions: Significance of changes in levels of blood electrolytes, gases, glucose, and insulin. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1980, 55, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deotare, S.T.; Chakrabarti, C.H. Effect of acephate (orthene) on tissue levels of thiamine, pyruvic acid, lactic acid, glycogen and blood sugar. Indian. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1981, 25, 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, U.K.; Pal, A.K.; Jha, G.J.; Jadhao, S.B. Pathophysiological effects of chronic toxicity with synthetic pyrethroid, organophosphate and chlorinated pesticides on bone health of broiler chicks. Toxicol. Pathol. 2004, 32, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, R.; Abdollahi, M. A review on mechanisms involved in hyperglycemia induced by organophosphorus insecticides. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2007, 88, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.C.; Wolfe, M.J. A brief overview of nonneoplastic hepatic toxicity in fish. Toxicol. Pathol. 2005, 33, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tendulkar, M.; Kulkarni, A. Cypermethrin-induced toxic effect on glycogen metabolism in estuarine clam, marcia opima (gmelin, 1791) of ratnagiri coast, maharashtra. J. Toxicol. 2012, 2012, 576804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- McLeay, D.J.; Brown, D.A. Effects of Acute Exposure to Bleached Kraft Pulpmill Effluent on Carbohydrate Metabolism of Juvenile Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) During Rest and Exercise. J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 1975, 32, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoola, S.O. Histopathological Effects of Glyphosate on Juvenile African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus). Am.-Eurasian J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2007, 4, 362–367. [Google Scholar]

- Bretaud, S.; Saglio, P.; Saligaut, C.; Auperin, B. Biochemical and behavioral effects of carbofuran in goldfish (Carassius auratus). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2002, 21, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.K.; Rajini, P.S. Reversible hyperglycemia in rats following acute exposure to acephate, an organophosphorus insecticide: Role of gluconeogenesis. Toxicology 2009, 257, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanova, S.; Georgieva, E.; Velcheva, I.; Iliev, I.; Vasileva, T.; Bivolarski, V.; Tomov, S.; Nyeste, K.; Antal, L.; Yancheva, V. Multi-Biomarker Assessment in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio, Linnaeus 1758) Liver after Acute Chlorpyrifos Exposure. Water 2020, 12, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, T.S.; Pant, J.C. Effect of organomercurial poisoning on the peripheral blood and metabolite levels of a freshwater fish. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 1985, 10, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak, P.; Roy, S.; Ganguly, A.; Mandi, M.; Dutta, A.; Das, K.; Nanda, S.; Sarkar, S.; Khatun, S.; Ghanty, S.; et al. Protective Potential of Vitamin C and E against Organophosphate Toxicity: Current Status and Perspective. J. Ecophysiol. Occup. Health 2022, 22, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.V. Sublethal effects of an organophosphorus insecticide (RPR-II) on biochemical parameters of tilapia, Oreochromis mossambicus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2006, 143, 492–498. [Google Scholar]

- Malarvizhi, A.; Kavitha, C.; Saravanan, M.; Ramesh, M. Carbamazepine (CBZ) induced enzymatic stress in gill, liver and muscle of a common carp, Cyprinus carpio. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2012, 24, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, G.; Shasmal, J. Concentration related responses of chlorpyriphos in antioxidant, anaerobic and protein synthesizing machinery of the freshwater fish, Heteropneustes fossilis. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2011, 99, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhijith, B.; Ramesh, M.; Rk, P. Responses of metabolic and antioxidant enzymatic activities in gill, liver and plasma of Catla catla during methyl parathion exposure. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2016, 77, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.F.; Mathieu, A.; Melvin, W.; Fancey, L. Acetylcholinesterase, an old biomarker with a new future? Field trials in association with two urban rivers and a paper mill in Newfoundland. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1996, 32, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casida, J.E.; Durkin, K.A. Anticholinesterase insecticide retrospective. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2013, 203, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonansea, R.I.; Wunderlin, D.A.; Ame, M.V. Behavioral swimming effects and acetylcholinesterase activity changes in Jenynsia multidentata exposed to chlorpyrifos and cypermethrin individually and in mixtures. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 129, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cuna, R.H.; Vazquez, G.R.; Piol, M.N.; Guerrero, N.V.; Maggese, M.C.; Nostro, F.L.L. Assessment of the acute toxicity of the organochlorine pesticide endosulfan in Cichlasoma dimerus (Teleostei, Perciformes). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2011, 74, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Yang, W.; Wang, D.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, R.; Ma, L.; Ge, C.; Li, X.; Huang, Z.; He, L.; et al. Chronic brain toxicity response of juvenile Chinese rare minnows (Gobiocypris rarus) to the neonicotinoid insecticides imidacloprid and nitenpyram. Chemosphere 2018, 210, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, C.E.D.; Pérez, M.R.; Acayaba, R.D.; Raimundo, C.C.M.; Dos Reis Martinez, C.B. DNA damage and oxidative stress induced by imidacloprid exposure in different tissues of the Neotropical fish Prochilodus lineatus. Chemosphere 2018, 195, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massoulie, J.; Pezzementi, L.; Bon, S.; Krejci, E.; Vallette, F.-M. Molecular and cellular biology of cholinesterases. Prog. Neurobiol. 1993, 41, 31–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.N.; Brimijoin, S. Cholinesterases and the fine line between poison and remedy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 153, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albendin, G.; Arellano, J.M.; Mánuel-Vez, M.P.; Sarasquete, C.; Arufe, M.I. Characterization and in vitro sensitivity of cholinesterases of gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) to organophosphate pesticides. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, M.H.; Key, P.B. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition in estuarine fish and invertebrates as an indicator of organophosphorus insecticide exposure and effects. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2001, 20, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boone, J.S.; Chambers, J.E. Time course of inhibition of cholinesterase and aliesterase activities, and nonprotein sulfhydryl levels following exposure to organophosphorus insecticides in mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis). Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1996, 29, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, D.A.; de Almeida, J.A.; Rantin, F.T.; Kalinin, A.L. Oxidative stress biomarkers in the freshwater characid fish, Brycon cephalus, exposed to organophosphorus insecticide Folisuper 600 (methyl parathion). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2006, 143, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousafzai, A.; Shakoori, A. Hepatic Responses of A Freshwater Fish Against Aquatic Pollution. Pak. J. Zool. 2011, 43, 209–221. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Mou, S.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, X. Risk Assessment of Fenpropathrin: Cause Hepatotoxicity and Nephrotoxicity in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reaction Pattern | Organ | Alteration | Importance Factor | Score Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Pirimiphos-Methyl | |||||

| 10 μg/L | 60 μg/L | |||||

| Changes in the circulatory system | Liver | Hyperaemia | WLC1 = 1 | 0A | 3B | 3B |

| Intracellular edema | WLC2 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Index for the circulatory system | ILC = 0 | ILC = 3 | ILC = 3 | |||

| Degenerative changes | Liver | Granular degeneration | WLR1 = 1 | 0A | 5B | 4C |

| Vacuolar degeneration | WLR2 = 2 | 0A | 4B | 4B | ||

| Necrobiosis | WLR3 = 2 | 0A | 1B | 1B | ||

| Necrosis | WLR4 = 3 | 0A | 1B | 2C | ||

| Fatty degeneration | WLR5 = 1 | 0A | 2B | 3C | ||

| Index for the degenerative changes | ILR = 0 | ILR = 20 | ILR = 23 | |||

| Proliferative changes | Liver | Hypertrophy | WLP1 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A |

| Index for the proliferative changes | ILP = 0 | ILP = 0 | ILP = 0 | |||

| Inflammation | Liver | Activation of RES | WLI1 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A |

| Lymphocyte infiltration | WLI2 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Index for the inflammatory processes | ILI = 0 | ILI = 0 | ILI = 0 | |||

| Index for the organ | IL = 0 | IL = 23 | IL = 26 | |||

| Reaction Pattern | Organ | Alteration | Importance Factor | Score Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Propamocarb Hydrochloride | |||||

| 40 μg/L | 80 μg/L | |||||

| Changes in the circulatory system | Liver | Hyperaemia | WLC1 = 1 | 0A | 4B | 4B |

| Intracellular edema | WLC2 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Index for the circulatory system | ILC = 0 | ILC = 4 | ILC = 4 | |||

| Degenerative changes | Liver | Granular degeneration | WLR1 = 1 | 0A | 5B | 5B |

| Vacuolar degeneration | WLR2 = 2 | 0A | 4B | 5C | ||

| Necrobiosis | WLR3 = 2 | 0A | 1B | 1B | ||

| Necrosis | WLR4 = 3 | 0A | 2B | 2B | ||

| Fatty degeneration | WLR5 = 1 | 0A | 2B | 4C | ||

| Index for the degenerative changes | ILR = 0 | ILR = 23 | ILR = 27 | |||

| Proliferative changes | Liver | Hypertrophy | WLP1 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A |

| Index for the proliferative changes | ILP = 0 | ILP = 0 | ILP = 0 | |||

| Inflammation | Liver | Activation of RES | WLI1 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A |

| Lymphocyte infiltration | WLI2 = 2 | 0A | 1B | 1B | ||

| Index for the inflammatory processes | ILI = 0 | ILI = 2 | ILI = 2 | |||

| Index for the organ | IL = 0 | IL = 29 | IL = 33 | |||

| Reaction Pattern | Organ | Alteration | Importance Factor | Score Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2,4-D | |||||

| 50 μg/L | 100 μg/L | |||||

| Changes in the circulatory system | Liver | Hyperaemia | WLC1 = 1 | 0A | 4B | 4B |

| Intracellular edema | WLC2 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Index for the circulatory system | ILC = 0 | ILC = 4 | ILC = 4 | |||

| Degenerative changes | Liver | Granular degeneration | WLR1 = 1 | 0A | 4B | 5C |

| Vacuolar degeneration | WLR2 = 2 | 0A | 4B | 5C | ||

| Necrobiosis | WLR3 = 2 | 0A | 1B | 1B | ||

| Necrosis | WLR4 = 3 | 0A | 2B | 2B | ||

| Fatty degeneration | WLR5 = 1 | 0A | 2B | 5C | ||

| Index for the degenerative changes | ILR = 0 | ILR = 22 | ILR = 28 | |||

| Proliferative changes | Liver | Hypertrophy | WLP1 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A |

| Index for the proliferative changes | ILP = 0 | ILP = 0 | ILP = 0 | |||

| Inflammation | Liver | Activation of RES | WLI1 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A |

| Lymphocyte infiltration | WLI2 = 2 | 0A | 1B | 1B | ||

| Index for the inflammatory processes | ILI = 0 | ILI = 2 | ILI = 2 | |||

| Index for the organ | IL = 0 | IL = 28 | IL = 34 | |||

| Experimental Pesticide | Controls | Pirimiphos-Methyl | Propamocarb Hydrochloride | 2,4-D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration μg/L | 10 μg/L | 60 μg/L | 40 μg/L | 80 μg/L | 50 μg/L | 100 μg/L | |

| Intensity of PAS-reaction in Common carp liver | 0.79 ± 0.43 A | 2.60 ± 0.55 B,C | 1.80 ± 0.84 B | 2.40 ± 0.89 B,C | 3.00 ± 0.71 B,C | 3.00 ± 0.71 B,C | 3.80 ± 1.10 B,C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yancheva, V.; Stoyanova, S.; Georgieva, E.; Kovacheva, E.; Bojarski, B.; Antal, L.; Uzochukwu, I.E.; Nyeste, K. Comparative Hepatic Toxicity of Pesticides in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, 1758): An Integrated Histopathological, Histochemical, and Enzymatic Biomarker Approach. J. Xenobiot. 2026, 16, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010019

Yancheva V, Stoyanova S, Georgieva E, Kovacheva E, Bojarski B, Antal L, Uzochukwu IE, Nyeste K. Comparative Hepatic Toxicity of Pesticides in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, 1758): An Integrated Histopathological, Histochemical, and Enzymatic Biomarker Approach. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2026; 16(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleYancheva, Vesela, Stela Stoyanova, Elenka Georgieva, Eleonora Kovacheva, Bartosz Bojarski, László Antal, Ifeanyi Emmanuel Uzochukwu, and Krisztián Nyeste. 2026. "Comparative Hepatic Toxicity of Pesticides in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, 1758): An Integrated Histopathological, Histochemical, and Enzymatic Biomarker Approach" Journal of Xenobiotics 16, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010019

APA StyleYancheva, V., Stoyanova, S., Georgieva, E., Kovacheva, E., Bojarski, B., Antal, L., Uzochukwu, I. E., & Nyeste, K. (2026). Comparative Hepatic Toxicity of Pesticides in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, 1758): An Integrated Histopathological, Histochemical, and Enzymatic Biomarker Approach. Journal of Xenobiotics, 16(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010019