From Aquifer to Tap: Comprehensive Quali-Quantitative Evaluation of Plastic Particles Along a Drinking Water Supply Chain of Milan (Northern Italy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

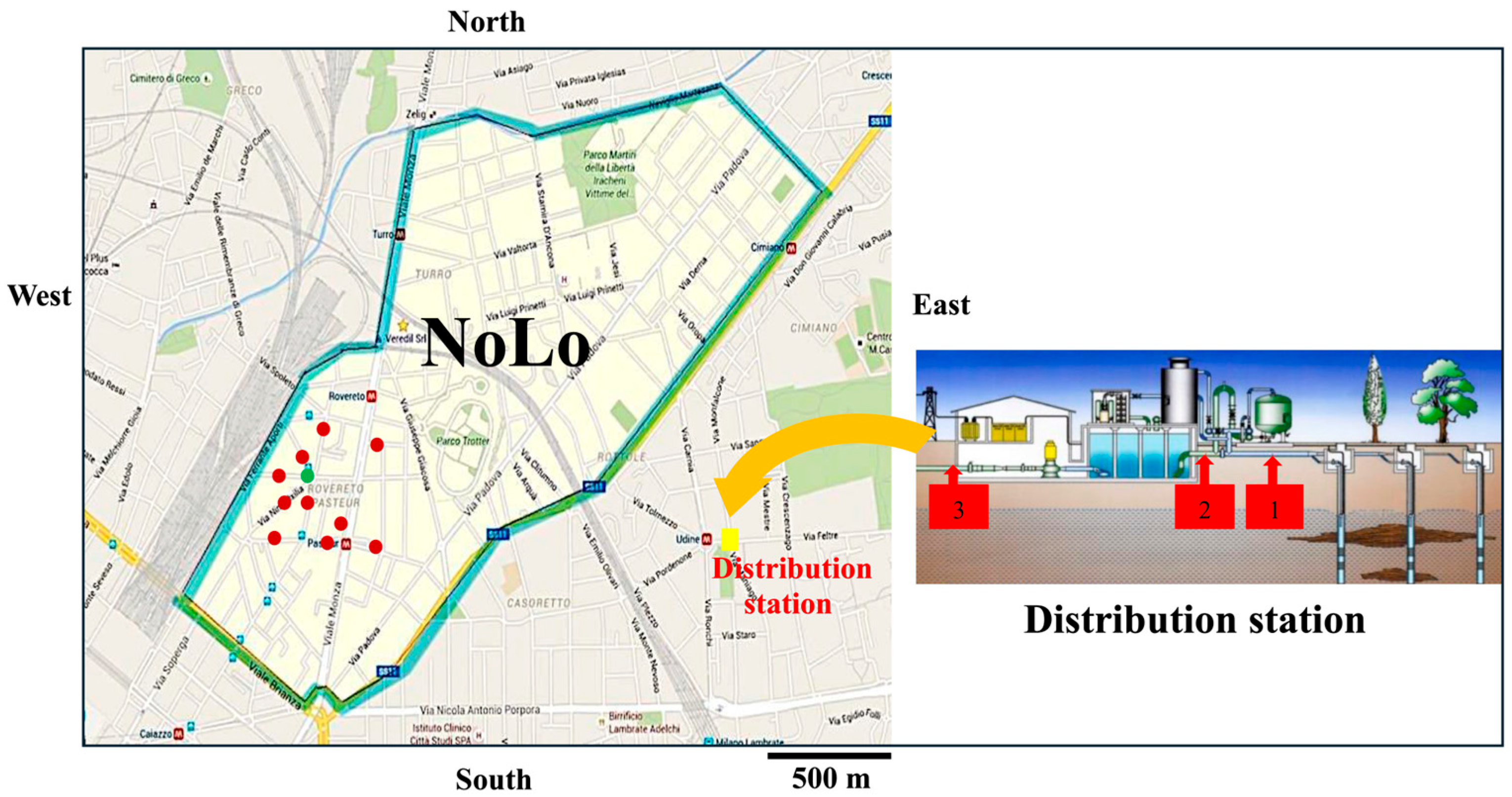

2.1. Characteristics of Milan’s Water Distribution System

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Sample Preparation and Instrumental Analyses

| Country | Water Source | Sampling Point | Instrumental | Shape | Polymers | Dimension | Plastic Concentration | Sampled Volume | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | - | taps | FTiR | fibers, fragments, films | PET, PP, PS, other | >10 mm | <LOD | 50 L × 3 (10–100 mm); 50 L × 17 (>100 mm) | [18] |

| Denmark | groundwater | taps | FTiR | Fragments, fibers | PP, PS, PET, other | >10 mm | <LOD | 50 L × 3 (10–100 mm); 50 L × 17 (>100 mm) | [19] |

| Norway | surface water | taps | FTiR | - | - | - | <LOD | 1 L × 3 × 24 samples | [20] |

| Germany | groundwater | taps | FTiR | fibers | PEST, PVC, PE, PA, epoxy resin | 50–150 mm | 0.7 part./m3 | 40 m3 | [34] |

| Germany | groundwater | taps | Raman | - | - | - | <LOQ | 0.5–1.5 m3 | [21] |

| Germany | groundwater | taps | Raman | - | PE, PET, PP, PA | 5–1000 mm | <LOQ | 1.3–7.2 m3 | [22] |

| Germany | - | taps | FTiR | fragments, fibers, pellets | PS, SEBS, PP, PEST, PE, PVC, other | >19 mm | 53 ± 29 part./L | 0.5 L × 3 | [35] |

| Finland | - | taps | FTiR | fragments, fibers | PS, SEBS, PP, PEST, PE, PVC, other | >19 mm | 47 ± 19 part./L | 0.5 L × 3 | [35] |

| France | - | taps | FTiR | fragments, fibers | PS, SEBS, PP, PEST, PE, PVC, other | >19 mm | 97 ± 45 part./L | 0.5 L × 3 | [35] |

| USA (California and Nevada) | - | taps | FTiR | fragments, fibers, pellets | PS, SEBS, PP, PEST, PE, PVC, other | >19 mm | 46 ± 32 part./L | 0.5 L × 3 | [35] |

| Mexico | groundwater | fountain | SEM-EDS, Raman | fibers | PEST, epoxy resin | >100 mm | 18 ± 7 part./L | 1 L × 3 × 42 samples | [36] |

| China | - | taps | Raman | fragments, fibers, pellets | PE, PP, PE + PP, PPS, PS, PET, other | 1–5000 mm | 440 ± 275 part./L | 1 L × 38 samples | [23] |

| China | surface water | taps | SEM, FTiR, Raman | fragments, fibers, pellets | PA, PVC, PP, PET, PE, other | 1–10 mm; 10–100 mm; >100 mm | 266 ± 56 part./L 63 ± 11 part./L 14 ± 5 part./L | 10 L × 3 × 4 samples | [37] |

| China | groundwater | taps | FTiR | fragments, fibers | PEST, PA, PS | >10 mm | 13.23 part./L | 1 L × 2 | [38] |

| Japan | groundwater and surface water | taps | FTiR | fragments, fibers, pellets | PS, SEBS, PP, PEST, PE, PVC, other | >19 mm | 29 ± 45 part./L | 0.5 L × 28 samples | [35] |

| Saudi Arabia | desalted water | taps | FTiR | - | PE | 25–500 mm | 1.8 part./L | 1 L | [39] |

| Sweden (Skåne) | groundwater | aquifer, supply pipelines | mFTiR-Py-GCMS | fragments, fibers | PEST, PA, PE, PVC, PS, PU, PP, acrylic | 5.2–374 mm | 174 ± 405 part./m3 (average) | 200–1100 L × 3 | [24] |

| Italy (Lazio) | groundwater | aquifer plant outlet water kiosks fountains taps glass and plastic bottles | m-Raman | fragments, fibers, pellets | PTFE, PP, PET, PE | 30–100 mm | 5.0 ± 1.5 part./L <1 part./L <LOQ 5 ± 1.5 part./L 2 ± 1 part./L <LOQ | 1 L × 34 samples | [25] |

| Italy (Milan) | groundwater | aquifer carbon filters accum. tank fountain taps | mFTiR | fragments, fibers, pellets, films | PEST, PAK, PTFE, PP, PU, PA, ABS, PS | 30–3600 mm | 0.9 ± 1.1 part./L 2.0 ± 2.8 part./L 0.3 ± 0.5 part./L 1.0 ± 0.0 part./L 1.9 ± 1.4 part./L | 1 L × 3 × 14 samples | Present study |

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

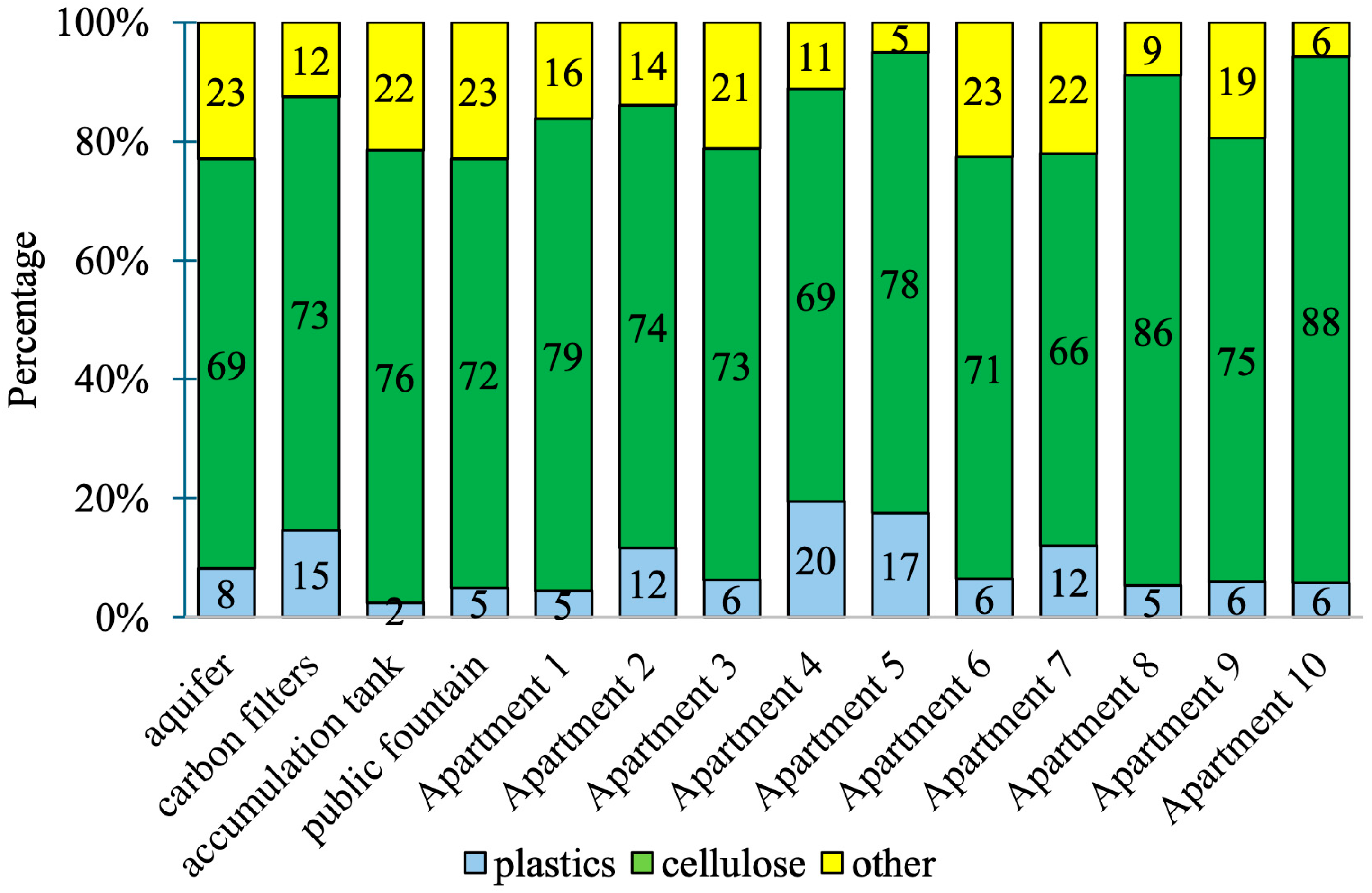

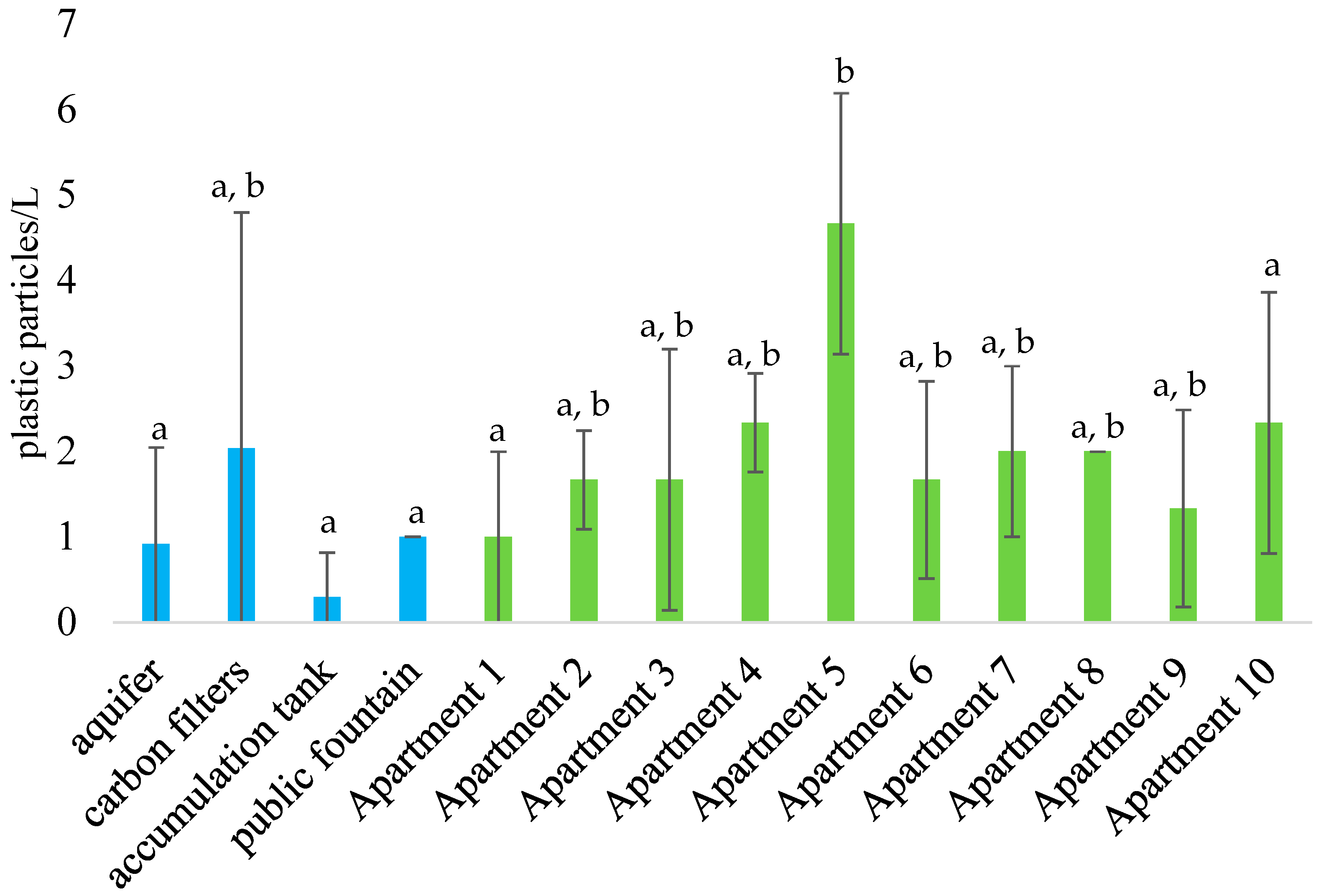

3.1. Quantitative Characterization

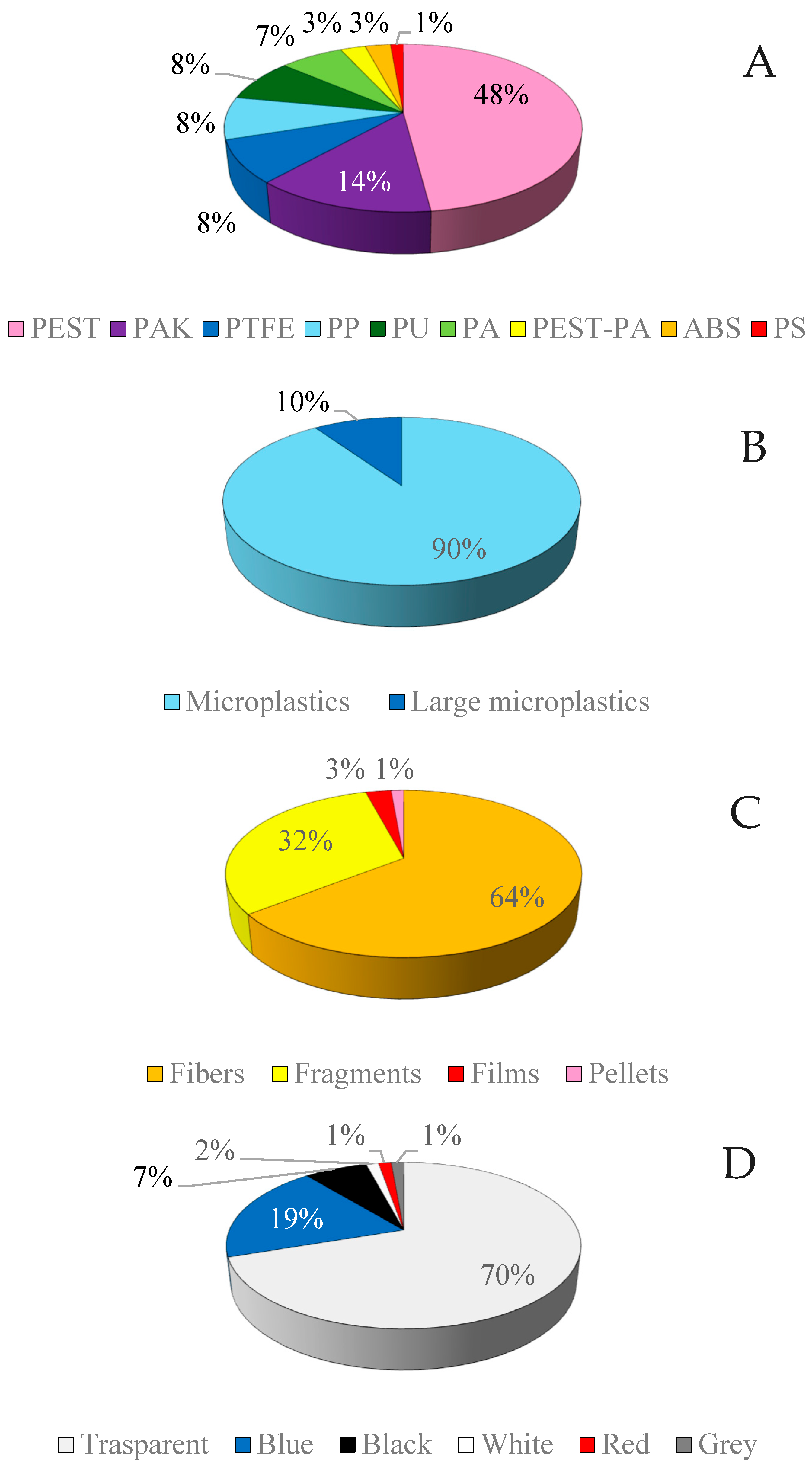

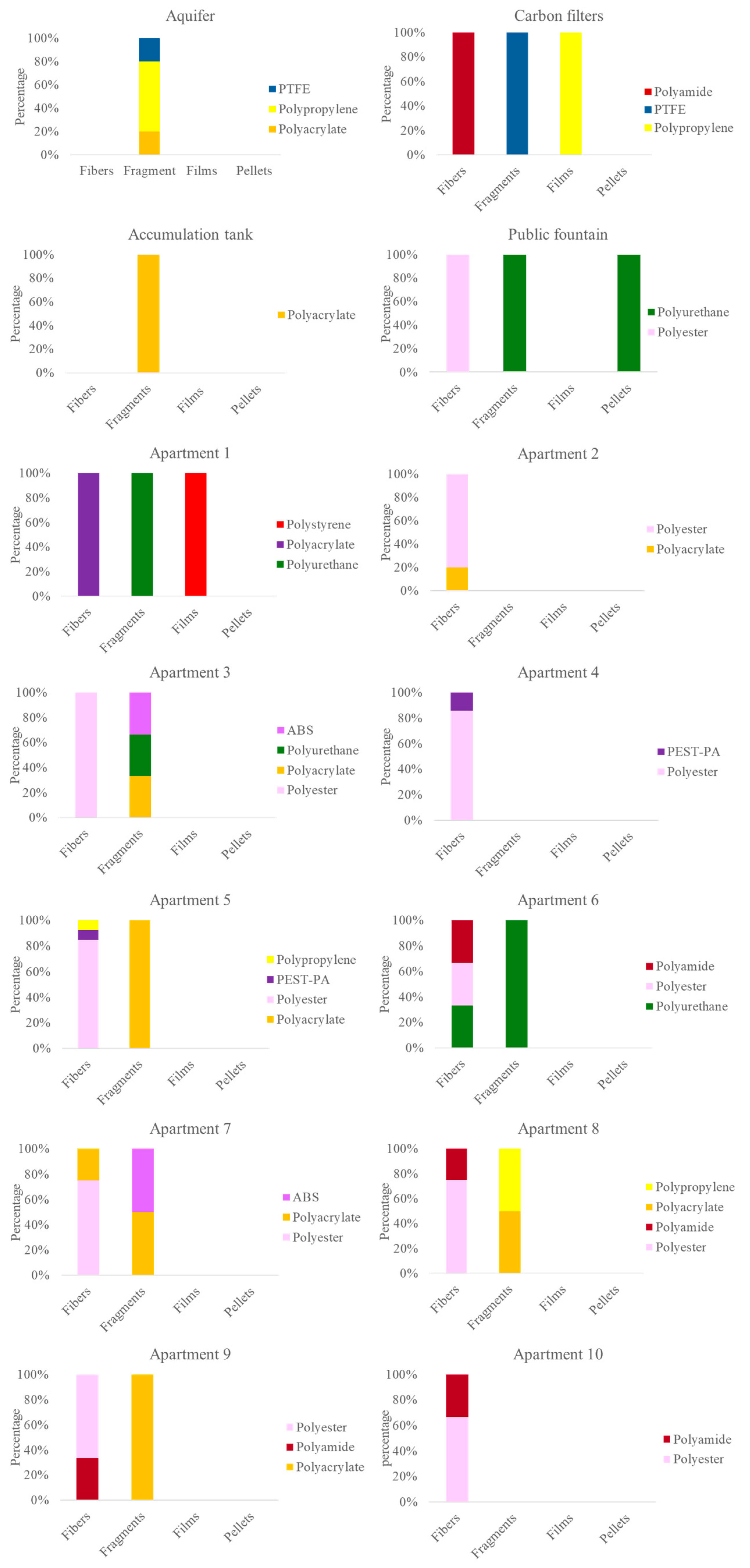

3.2. Qualitative Characterization

4. Discussion

4.1. Characterization of Plastic Contamination Along the Drinking Water Supply Chain

4.2. Comparison of Plastic Levels Along Drinking Water Supply Chains Worldwide

4.3. Human Exposure Assessment

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: Fourth Edition Incorporating the First Addendum; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; p. 631. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). The United Nations World Water Development Report 2021: Valuing Water; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; p. 227. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Europe’s State of Water 2024: The Need for Improved Water Resilience; EEA Report, No. 08/2024; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environmental Agency (EEA). Drivers of and Pressures Arising from Selected Key Water Management Challenges—A European Overview; EEA Report, No. 9/2021; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). The Human Rights to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation: Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly; A/RES/70/169. GAOR, 70th Sess., Suppl. No. 49; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2016; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). The United Nations World Water Development Report 2023: Partnerships and Cooperation for Water; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023; p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- European Environmental Agency (EEA). Europe’s Groundwater—A Key Resource Under Pressure; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.; Cheema, S.; Chaabna, K.; Lowenfels, A.B.; Mamtani, R. Rethinking bottled water in public health discourse. BMJ Glob. Health 2024, 9, e015226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Scherer, U.; Schaub, S.; Horn, H. Making Europe go from bottles to the tap: Political and societal attempts to induce behavioral change. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.-Water 2020, 7, e1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Alaimo, L.S.; Ciaccio, T.; Vrontis, D.; Fiore, M. Plastic or not plastic? That’s the problem: Analysing the Italian students purchasing behavior of mineral water bottles made with eco-friendly packaging. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 179, 106060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicarelli, V.; Bux, C.; Lagioia, G. Environmental Accounting for the Circularization of the Packaged Water Sector in Italy. In Innovation, Quality and Sustainability for a Resilient Circular Economy Springer; Lagioia, G., Paiano, A., Amicarelli, V., Gallucci, T., Ingrao, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parag, Y.; Elimelech, E.; Opher, T. Bottled Water: An Evidence-Based Overview of Economic Viability, Environmental Impact, and Social Equity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, R.; Vandermoere, F.; Van Winckel, T.; Halet, D.; Joos, P.; Van Den Steen, K.; Van Meenen, E.; Blust, R.; Borregán-Ochando, E.; Vlaeminck, S.E. Bottle or tap? Toward an integrated approach to water type consumption. Water Res. 2020, 173, 115578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; p. 541. [Google Scholar]

- Legislative Decree (18/2023). Available online: www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2023/03/06/23G00025/sg (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Swain, P.R.; Parida, P.K.; Majhi, P.J.; Behera, B.K.; Das, B.K. Microplastics as Emerging Contaminants: Challenges in Inland Aquatic Food Web. Water 2025, 17, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decision EU 2024/1441. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dec_del/2024/1441/oj/eng (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Strand, J.; Feld, L.; Murphy, F.; Mackevica, A.; Hartmann, N.B. Analysis of Microplastic Particles in Danish Drinking Water; Scientific Report from DCE—Danish Centre for Environment and Energy; Aarhus University: Aarhus, Denmark, 2018; p. 291. [Google Scholar]

- Feld, L.; Silva, V.H.D.; Murphy, F.; Hartmann, N.B.; Strand, J. A study of microplastic particles in Danish tap water. Water 2021, 13, 2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl, W.; Eftekhardadkhah, M.; Svendsen, C. Mapping microplastic in Norwegian drinking water. Atlantic 2018, 185, 491–497. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, F.; Kerpen, J.; Wolff, S.; Langer, R.; Eschweiler, V. Investigation of microplastics contamination in drinking water of a German city. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 143421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittroff, M.; Müller, Y.K.; Witzig, C.S.; Scheurer, M.; Storck, F.R.; Zumbülte, N. Microplastic analysis in drinking water based on fractionated filtration sampling and Raman microspectroscopy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 59439–59451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Jiang, Q.; Hu, X.; Zhong, X. Occurrence and identification of microplastics in tap water from China. Chemosphere 2020, 252, 126493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirstein, I.V.; Hensel, F.; Gomiero, A.; Iordachescu, L.; Vianello, A.; Wittgren, H.B.; Vollertsen, J. Drinking plastics?—Quantification and qualification of microplastics in drinking water distribution systems by μFTIR and Py-GCMS. Water Res. 2021, 188, 116519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaleone, E.; Mattei, D.; Fuscoletti, V.; Lucentini, L.; Favero, G.; Cecchini, G.; Frugis, A.; Gioia, V.; Lazzazzara, M. Microplastic in Drinking Water: A Pilot Study. Microplastics 2024, 3, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2020/2184. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2020/2184/oj/eng (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Magni, S.; Nigro, L.; Della Torre, C.; Binelli, A. Characterization of plastics and their ecotoxicological effects in the Lambro River (N. Italy). J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magni, S.; Della Torre, C.; Nigro, L.; Binelli, A. Can COVID-19 pandemic change plastic contamination? The Case study of seven watercourses in the metropolitan city of Milan (N. Italy). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binelli, A.; Magni, S.; Della Torre, C.; Sbarberi, R.; Cremonesi, C.; Galafassi, S. Monthly variability of floating plastic contamination in Lake Maggiore (Northern Italy). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binelli, A.; Tognetto, M.; Cremonesi, C.; Della Torre, C.; Caorsi, G.; Magni, S. Dietary exposure and risk assessment of plastic particles in cow’s milk stored in various packaging materials. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 492, 138052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.centraleacquamilano.it/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Available online: https://latuacqua.it/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- ISO/TR 21960:2020; Plastics—Environmental Aspects—State of Knowledge and Methodologies. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Mintenig, S.M.; Löder, M.G.; Primpke, S.; Gerdts, G. Low numbers of microplastics detected in drinking water from ground water sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukotaka, A.; Kataoka, T.; Nihei, Y. Rapid analytical method for characterization and quantification of microplastics in tap water using a Fourier-transform infrared microscope. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shruti, V.C.; Pérez-Guevara, F.; Kutralam-Muniasamy, G. Metro station free drinking water fountain-A potential “microplastics hotspot” for human consumption. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 261, 114227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Zeng, Z.; Wen, X.; Ren, X.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, R. Presence of microplastics in drinking water from freshwater sources: The investigation in Changsha, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 42313–42324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Zheng, B.; Li, Z.; Cai, C.; Peng, Z.; Zhao, P.; Tian, Y. Occurrence and distribution of microplastics in water supply systems: In water and pipe scales. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 803, 150004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiman, L.; Aljomah, A.; Bineid, M.; Aljejdh, F.M.; Aldawsari, F.; Liebmann, B.; Lomako, I.; Sexlinger, K.; Alarfaj, R. The occurrence and dietary intake related to the presence of microplastics in drinking water in Saudi Arabia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaroli, S.; Lancia, M.; Lee, J.; Ben, Y.; Giannecchini, R.; Castelvetro, V.; Petrini, R.; Zheng, C.; Re, V. Limits, challenges, and opportunities of sampling groundwater wells with plastic casings for microplastic investigations. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severini, E.; Ducci, L.; Sutti, A.; Robottom, S.; Sutti, S.; Celico, F. River–groundwater interaction and recharge effects on microplastics contamination of groundwater in confined alluvial aquifers. Water 2022, 14, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, E.; Arduini, C.; Belli, A.; Carminati, A.; di Palma, F.; Giudici, M.; Piazzolla, D.; Villa, D. A large scale model of ground water flow in Milano (Italy). In Geophysical Research Abstracts; Copernicus Publications: Göttingen, Germany, 2002; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Binelli, A.; Della Torre, C.; Nigro, L.; Riccardi, N.; Magni, S. A realistic approach for the assessment of plastic contamination and its ecotoxicological consequences: A case study in the metropolitan city of Milan (N. Italy). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanumalayan, E.; Joshi, G.M. Performance properties and applications of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)—A review. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2018, 1, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo, E. Analysis of Premature Failure of a PVC Water Pipe. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2023, 23, 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzorati, A. Analisi Dell’influenza Delle Gallerie Metropolitane Sull’innalzamento del Livello di Falda: Il Caso di Milano. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy, 2014; p. 122. [Google Scholar]

- Pivokonsky, M.; Cermakova, L.; Novotna, K.; Peer, P.; Cajthaml, T.; Janda, V. Occurrence of microplastics in raw and treated drinking water. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 643, 1644–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivokonsky, M.; Pivokonská, L.; Novotná, K.; Čermáková, L.; Klimtová, M. Occurrence and fate of microplastics at two different drinking water treatment plants within a river catchment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lin, T.; Chen, W. Occurrence and removal of microplastics in an advanced drinking water treatment plant (ADWTP). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 700, 134520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäuerlein, P.S.; Hofman-Caris, R.C.H.M.; Pieke, E.N.; ter Laak, T.L. Fate of microplastics in the drinking water production. Water Res. 2022, 221, 118790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.B. Adsorption in water and used water purification. In Handbook of Water and Used Water Purification; Lahnsteiner, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Meng, Y.; Qin, L.; Shen, M.; Qin, T.; Chen, X.; Chai, B.; Liu, Y.; Dou, Y.; Duan, X. Occurrence and removal efficiency of microplastics in four drinking water treatment plants in Zhengzhou, China. Water 2024, 16, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursi, A.; Baratta, M.; Easton, T.; Chatzisymeon, E.; Chidichimo, F.; De Biase, M.; De Filpo, G. Microplastics in aquatic systems, a comprehensive review: Origination, accumulation, impact, and removal technologies. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 28318–28340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, N.A.; Zoppas, F.M.; Devard, A.; González Muñoz, M.D.P.; García, G.; Marchesini, F.A. Recent advances in microplastics removal from water with special attention given to photocatalytic degradation: Review of scientific research. Microplastics 2023, 2, 278–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kang, S.; Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Gao, T.; Sillanpää, M. Atmospheric microplastics: A review on current status and perspectives. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 203, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambino, I.; Bagordo, F.; Grassi, T.; Panico, A.; De Donno, A. Occurrence of microplastics in tap and bottled water: Current knowledge. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acarer, S. Abundance and characteristics of microplastics in drinking water treatment plants, distribution systems, water from refill kiosks, tap waters and bottled waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 884, 163866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, N.-D.; Vo, D.-H.T.; Pham, M.-D.; Nguyen, V.-T.; Nguyen, T.-B.; Le, L.-T.; Mukhtar, H.; Nguyen, H.-V.; Visvanathan, C.; Bui, X.-T. Microplastics contamination in water supply system and treatment processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosuth, M.; Mason, S.A.; Wattenberg, E.V. Anthropogenic contamination of tap water, beer, and sea salt. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuri, G.; Karanasiou, A.; Lacorte, S. Microplastics: Human exposure assessment through air, water, and food. Environ. Internat. 2023, 179, 108150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageel, H.K.; Harrad, S.; Abdallah, M.A.E. Occurrence, human exposure, and risk of microplastics in the indoor environment. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2022, 24, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, K.D.; Covernton, G.A.; Davies, H.L.; Dower, J.F.; Juanes, F.; Dudas, S.E. Human Consumption of Microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7068–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, E.G.; Li, J.; Chen, Q.; Ma, L.; Zeng, E.Y.; Shi, H. A review of microplastics in table salt, drinking water, and air: Direct human exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3740–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senathirajah, K.; Attwood, S.; Bhagwat, G.; Carbery, M.; Wilson, S.; Palanisami, T. Estimation of the mass of microplastics ingested–A pivotal first step towards human health risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 404, 124004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SINU, Società Italiana di Nutrizione Umana. Livelli di Assunzione di Riferimento di Nutrienti ed Energia per la Popolazione Italiana. V Versione; Biomedia: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Sampling Point | Mean Concentration (Particles ± St. Dev./L) | Min Value (Particles/L) | Max Value (Particles/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| aquifer | 0.9 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | 2.8 |

| carbon filters | 2.0 ± 2.8 | 0.0 | 5.2 |

| accumulation tank | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| public fountain | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| apartments 1–10 | 1.9 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 6.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Binelli, A.; Cappelletti, A.; Cremonesi, C.; Della Torre, C.; Caorsi, G.; Magni, S. From Aquifer to Tap: Comprehensive Quali-Quantitative Evaluation of Plastic Particles Along a Drinking Water Supply Chain of Milan (Northern Italy). J. Xenobiot. 2026, 16, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010018

Binelli A, Cappelletti A, Cremonesi C, Della Torre C, Caorsi G, Magni S. From Aquifer to Tap: Comprehensive Quali-Quantitative Evaluation of Plastic Particles Along a Drinking Water Supply Chain of Milan (Northern Italy). Journal of Xenobiotics. 2026; 16(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleBinelli, Andrea, Alberto Cappelletti, Cristina Cremonesi, Camilla Della Torre, Giada Caorsi, and Stefano Magni. 2026. "From Aquifer to Tap: Comprehensive Quali-Quantitative Evaluation of Plastic Particles Along a Drinking Water Supply Chain of Milan (Northern Italy)" Journal of Xenobiotics 16, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010018

APA StyleBinelli, A., Cappelletti, A., Cremonesi, C., Della Torre, C., Caorsi, G., & Magni, S. (2026). From Aquifer to Tap: Comprehensive Quali-Quantitative Evaluation of Plastic Particles Along a Drinking Water Supply Chain of Milan (Northern Italy). Journal of Xenobiotics, 16(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010018