Carbonation of Calcined Clay Dolomite for the Removal of Co(II): Performance and Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Carbonation Tests of the Calcined Clay Dolomite

2.3. Removal Tests of Co(II) by CCCD

2.4. Characterization

3. Results and Discussions

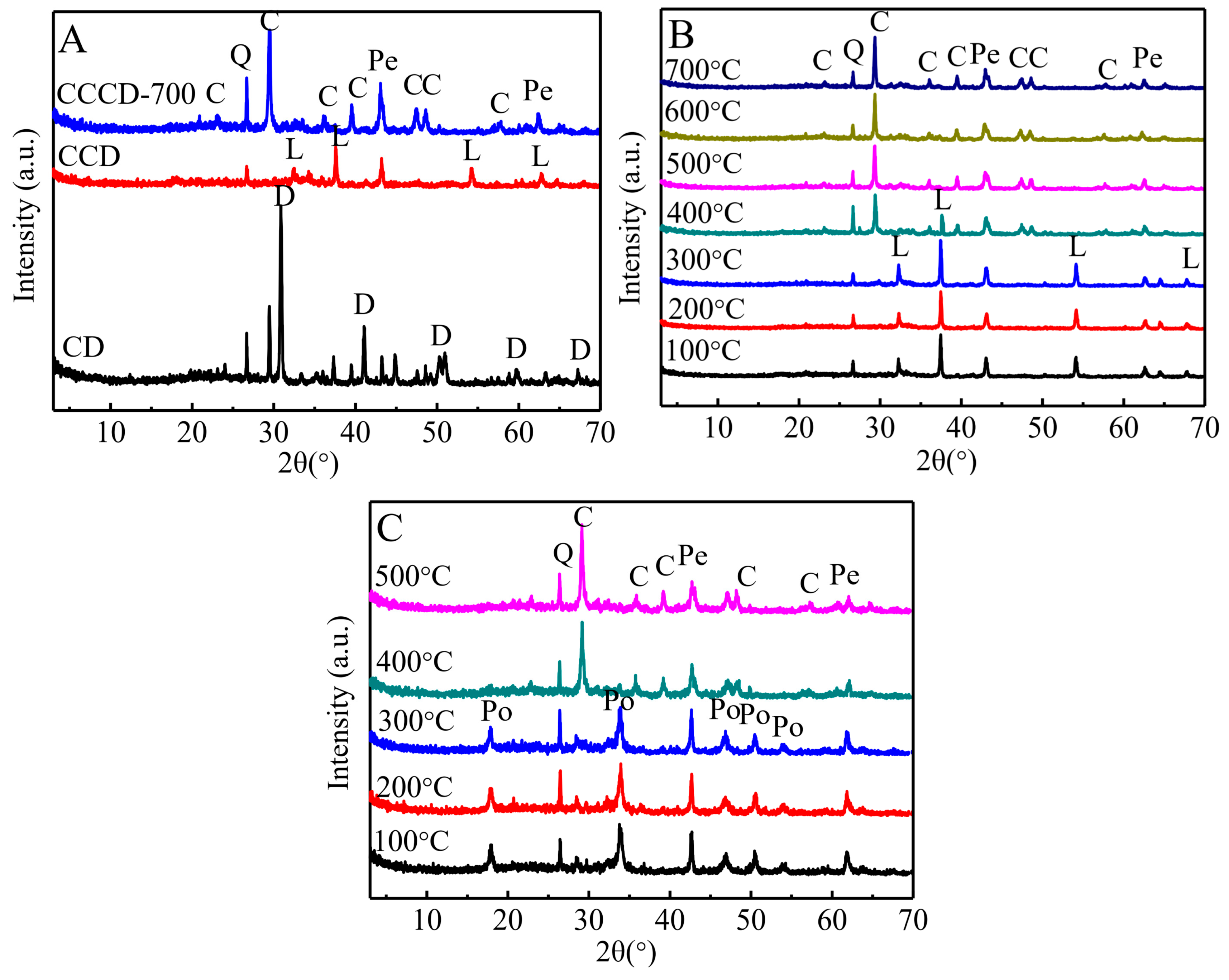

3.1. Components of Clayey Dolomite

3.2. Carbonated Product

3.3. Batch Experiments for Co(II) Removal

3.3.1. Cobalt Removal Performance

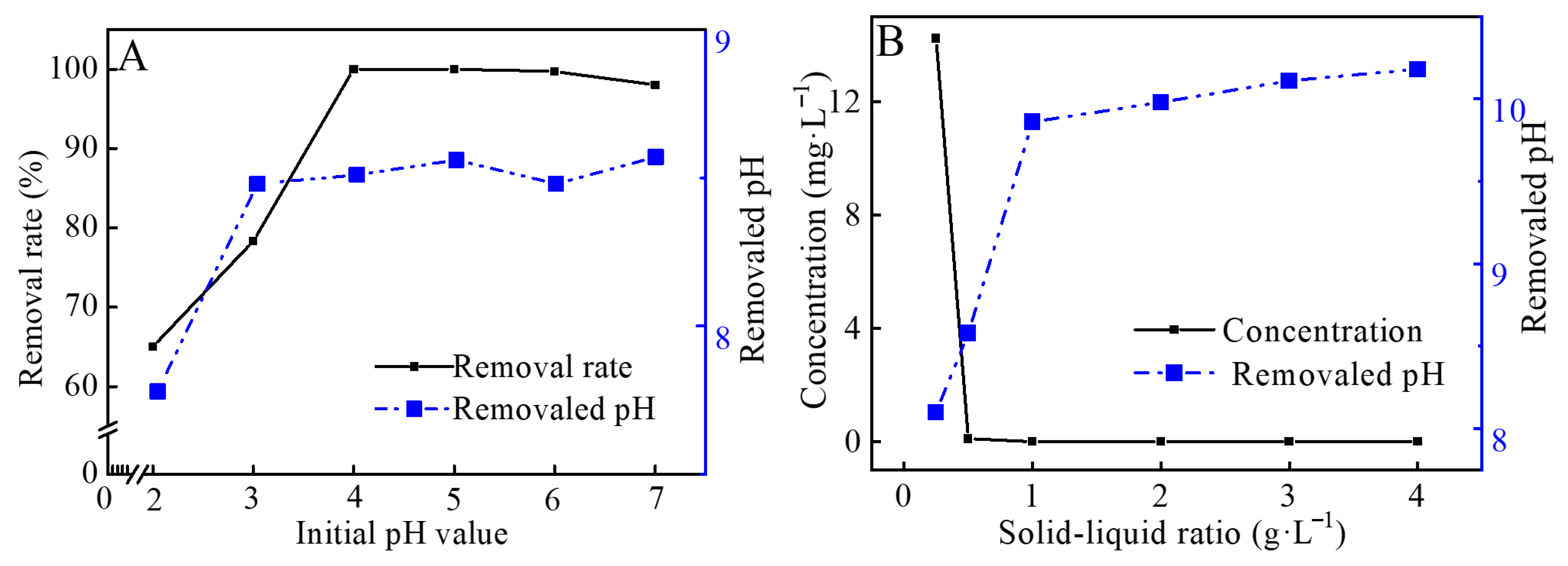

3.3.2. Effects of Initial pH and Solid-Liquid Ratio

3.3.3. Kinetic

3.3.4. Equilibrium Isotherm Models

3.3.5. Thermodynamic

3.4. The Removal Mechanism of Cobalt by CCCD

3.5. Long-Term Continuous-Flow Performance of CCCD

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The pre-hydration treatment substantially enhanced carbonation efficiency. It lowered the temperature required for complete carbonation from 500 °C to 400 °C. This provides a more energy-efficient preparation strategy.

- (2)

- CCCD exhibited excellent Co(II) removal performance under weakly acidic conditions (initial pH 4, 318 K). The apparent maximum removal capacity reached 621.1 mg·g−1. Continuous flow column tests verified strong long-term stability. The system maintained approximately 99.0% removal efficiency and a stable effluent pH of about 8.5 over one month.

- (3)

- Visual MINTEQ calculations and solid phase characterizations (XRD, XPS, TEM) indicate that Co(II) immobilization is dominated by mineral water interface precipitation rather than extensive bulk precipitation at the measured effluent pH. The microscale alkaline environment at calcite and periclase surfaces promotes Co(OH)2 and CoCO3 formation and retention on CCCD particles, while maintaining a stable, mildly alkaline effluent.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bahini, Y.; Mushtaq, R.; Bahoo, S. Global energy transition: The vital role of cobalt in renewable energy. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470, 143306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyssens, L.; Vinck, B.; Van Der Straeten, C.; Wuyts, F.; Maes, L. Cobalt toxicity in humans—A review of the potential sources and systemic health effects. Toxicology 2017, 387, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, D.; Rizzo, F.; Mangialardi, T.; Medici, F.; Caruso, G.; Di Palma, L.; Giannetti, F. Cementitious mortar for Intermediate and Low-Level Radioactive waste confinement: Matrix optimization and leaching. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2025, 441, 114165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Gibb, H.J.; Howe, P. Cobalt and Inorganic Cobalt Compounds; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; pp. 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Samal, P.; Mohanty, A.K.; Khaoash, S.; Mishra, P.; Ramaswamy, K. Health risk assessment and hydrogeochemical modelling of groundwater due to heavy metals contaminants at Basundhara coal mining region, India. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2024, 104, 735–754. [Google Scholar]

- Kasera, N.; Kolar, P.; Hall, S.G. Nitrogen-doped biochars as adsorbents for mitigation of heavy metals and organics from water: A review. Biochar 2022, 4, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Morton, D.W.; Johnson, B.B.; Pramanik, B.K.; Mainali, B.; Angove, M.J. Opportunities and constraints of using the innovative adsorbents for the removal of cobalt(II) from wastewater: A review. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2018, 10, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenawy, E.-R.; Ghfar, A.A.; Naushad, M.; Alothman, Z.A.; Habila, M.A.; Albadarin, A.B. Efficient removal of Co(II) metal ion from aqueous solution using cost-effective oxidized activated carbon: Kinetic and isotherm studies. Desalination Water Treat. 2017, 70, 220–226. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, S.; Singh, H.; Sharma, S.; Barman, P.; Saini, A.; Verma, G. Synthesis and characterization of graphene oxide-bovine serum albumin conjugate membrane for adsorptive removal of Cobalt(II) from water. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 18, 3915–3928. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanets, A.; Srivastava, V.; Kitikova, N.; Shashkova, I.; Sillanpää, M. Kinetic and thermodynamic studies of the Co (II) and Ni (II) ions removal from aqueous solutions by Ca-Mg phosphates. Chemosphere 2017, 171, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhaei, M.; Mokhtari, H.R.; Vatanpour, V.; Rezaei, K. Investigating the Effectiveness of Natural Zeolite (Clinoptilolite) for the Removal of Lead, Cadmium, and Cobalt Heavy Metals in the Western Parts of Iran’s Varamin Aquifer. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuránek, M.; Melichová, Z.; Thomas, M. Removal of cadmium and cobalt from water by Slovak bentonites: Efficiency, isotherms, and kinetic study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 29199–29217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, J.; Toyofuku, T.; Nishimura, K.; Ueda, A.; Nagai, Y.; Kawada, S.; Teng, H.H.; Nagai, T. Direct Two-Dimensional Time Series Observation of pH Distribution around Dissolving Calcium Carbonate Crystals in Aqueous Solution. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 4212–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.K. A review on the adsorption of heavy metals by clay minerals, with special focus on the past decade. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 308, 438–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Xie, J.; Li, H.; Chen, T.; Chen, P.; Chen, D. An insight into the carbonation of calcined clayey dolomite and its performance to remove Cd (II). Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 150, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Zou, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, D.; Zhou, Y. Removal of Pb(II) from Aqueous Solutions by Periclase/Calcite Nanocomposites. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2019, 230, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Chen, T.; Xing, B.; Liu, H.; Xie, Q.; Li, H.; Wu, Y. The thermochemical activity of dolomite occurred in dolomite-palygorskite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 119, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfrin, J.; Junior, A.C.G.; Schwantes, D.; Zimmermann, J.; Junior, E.C. Effective Cd2+ removal from water using novel micro-mesoporous activated carbons obtained from tobacco: CCD approach, optimization, kinetic, and isotherm studies. J. Environ. Health Sci. 2021, 19, 1851–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uysal, O.G.; Demir, A.; Goren, N. Investigation of cobalt (II) adsorption from aqueous solution using Genista albida as a low-cost adsorbent: Optimization based upon response surface methodology. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2022, 21, 637–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataria, N.; Garg, V. Optimization of Pb (II) and Cd (II) adsorption onto ZnO nanoflowers using central composite design: Isotherms and kinetics modelling. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 271, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, M.H.; Yetilmezsoy, K.; Salari, M.; Heidarinejad, Z.; Yousefi, M.; Sillanpää, M. Adsorptive removal of cobalt (II) from aqueous solutions using multi-walled carbon nanotubes and γ-alumina as novel adsorbents: Modelling and optimization based on response surface methodology and artificial neural network. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 299, 112154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, J. Comparison of linearization methods for modeling the Langmuir adsorption isotherm. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 296, 111850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigdorowitsch, M.; Pchelintsev, A.; Tsygankova, L.; Tanygina, E. Freundlich isotherm: An adsorption model complete framework. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Awaji, N.; Boukriba, M.; Idriss, H.; Ben Aissa, M.A.; Bououdina, M.; Modwi, A. Green Synthesis Ca-MgO Nanosorbent for the Uptake of Cobalt Ions from Aqueous Media. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 9174538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaligh, A.; Zavvar, M.H.; Rashidi, A. Ultrasonic assisted removal of Ni(II) and Co(II) ions from aqueous solutions by carboxylated nanoporous graphene. Appl. Chem. Today 2016, 11, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemian, S.; Saffari, H.; Ragabion, S. Adsorption of cobalt (II) from aqueous solutions by Fe3O4/bentonite nanocomposite. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2015, 226, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Kaddour, S.; Trari, M. Kinetic and equilibrium studies of cobalt adsorption on apricot stone activated carbon. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014, 20, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Kong, L.; Huang, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Sun, B.; Jin, Z.; Wang, J.; Huang, X.-J.; et al. Removal of cobalt ions from aqueous solution by an amination graphene oxide nanocomposite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 270, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, K.G.; Gupta, S.S. Adsorption of Fe (III), Co (II) and Ni (II) on ZrO-kaolinite and ZrO-montmorillonite surfaces in aqueous medium. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2008, 317, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfatah, A.; Abdel-Gawad, O.F.; Elzanaty, A.M.; Rabie, A.M.; Mohamed, F. Fabrication and optimization of poly(ortho-aminophenol) doped glycerol for efficient removal of cobalt ion from wastewater. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 345, 117034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingamdinne, L.P.; Koduru, J.R.; Roh, H.; Choi, Y.-L.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Yang, J.-K. Adsorption removal of Co (II) from waste-water using graphene oxide. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 165, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osińska, M. Removal of lead (II), copper (II), cobalt (II) and nickel (II) ions from aqueous solutions using carbon gels. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2017, 81, 678–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Deng, L.; Fan, X.; Li, K.; Lu, H.; Li, W. Removal of heavy metal ion cobalt (II) from wastewater via adsorption method using microcrystalline cellulose-magnesium hydroxide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 189, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Chai, S.-S.; Zhang, W.-B.; Guo, S.-B.; Han, X.-W.; Guo, Y.-W.; Bao, X.; Ma, X.-J. Cobalt boride on clay minerals for electrochemical capacitance. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 218, 106416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Zhang, C.; Liang, Y.; Qiu, W.; Kong, F.; He, X.; Chen, M.; Liang, P.; Zhang, Z. Electrospun cobalt Prussian blue analogue-derived nanofibers for oxygen reduction reaction and lithium-ion batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 599, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Joshi, P.; Mukhopadhyay, S.M.; Higgins, S.R. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic studies of dolomite surfaces exposed to undersaturated and supersaturated aqueous solutions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2006, 70, 3342–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zuo, H.; Xu, D.; Liu, W.; Dan, H.; Liu, X.; Lin, S.; Hou, P. Heat-treated Dolomite-palygorskite clay supported MnOx catalysts prepared by various methods for low temperature selective catalytic reduction (SCR) with NH3. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 152, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concentration of Co(II) (mg·L−1) | Pseudo-First-Order | Pseudo-Second-Order | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qe (mg·g−1) | K1 | R2 | Qe (mg·g−1) | K2 | R2 | |

| 50 | 36.97 | 0.03 | 0.9829 | 72.3 | 0.0024 | 0.9995 |

| 100 | 73.65 | 0.01 | 0.9861 | 116.69 | 0.0004 | 0.9895 |

| Langmuir | Freundlich | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T/K | qm (mg·g−1) | KL (L·mg−1) | R2 | KF (mg·g−1) | 1/n | R2 |

| 298 | 591.7 | 0.0746 | 0.9748 | 285.38 | 0.1239 | 0.757 |

| 308 | 602.4 | 0.0621 | 0.9419 | 192.32 | 0.2103 | 0.8607 |

| 318 | 621.1 | 0.0615 | 0.9679 | 192.95 | 0.2143 | 0.8958 |

| Adsorbent | Time (h) | pH | T (°C) | Co(II) (mg·L−1) | Dose (g·L−1) | Qmax (mg·g−1) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidized activated carbon | 2 | 4 | / | 50 | 0.03–0.1 | 83.6 | [8] |

| Carboxylated nanoporous graphene | 0.2 | 6 | 25 | 50 | 0.12 | 87.7 | [25] |

| Fe3O4/bentonite | 1.5 | 8 | 25 | 800 | 2 | 18.8 | [26] |

| Apricot stone activated carbon | 1.5 | 2–13.5 | 25–34 | 10–80 | 5–50 | 111.1 | [27] |

| Amination graphene oxide nanocomposite | 12 | 6 | 25 | 30 | 0.3 | 116.4 | [28] |

| ZrO-Kaolinite | 0.33–4 | 1–10 | 30–40 | 10–250 | 2–6 | 0.2 | [29] |

| ZrO-montmorillonite | 0.33–4 | 1–10 | 30–40 | 10–250 | 2–6 | 0.2 | [29] |

| GO-BSA membrane | 1.3 | 5–9 | 25–30 | 20–120 | 0.1 | 180 | [9] |

| Doped glycerol | 1.2 | 2–10 | 25 | 10–100 | 0.5–1 | 117.9 | [30] |

| Ca-dopped MgO | 0.3 | 1–8 | / | 5–200 | 0.4 | 469.5 | [24] |

| Graphene oxide | 1 | 5.5 | 25 | 2–25 | 1 | 21.3 | [31] |

| Carbon gels | 48 | 3–7 | 25 | 10–50 | 2 | 5.5 | [32] |

| CCCD | 6 | 4 | 25 | 10–100 | 0.5 | 621.1 | This work |

| T (K) | KL (mg·g−1) | ΔG (kJ·mol−1) | ΔH (kJ·mol−1) | ΔS (J·mol−1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | 0.0746 | 6.431 | −7.68 | −47.57 | 0.8027 |

| 308 | 0.0621 | 7.117 | |||

| 318 | 0.0615 | 7.373 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Xu, J.; Gao, T.; Hong, X.; Pan, F.; Sun, F.; Huang, K.; Wang, D.; Chen, T.; Zhang, P. Carbonation of Calcined Clay Dolomite for the Removal of Co(II): Performance and Mechanism. J. Xenobiot. 2026, 16, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010013

Wang C, Xu J, Gao T, Hong X, Pan F, Sun F, Huang K, Wang D, Chen T, Zhang P. Carbonation of Calcined Clay Dolomite for the Removal of Co(II): Performance and Mechanism. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2026; 16(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Can, Jingxian Xu, Tingting Gao, Xiaomei Hong, Fakang Pan, Fuwei Sun, Kai Huang, Dejian Wang, Tianhu Chen, and Ping Zhang. 2026. "Carbonation of Calcined Clay Dolomite for the Removal of Co(II): Performance and Mechanism" Journal of Xenobiotics 16, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010013

APA StyleWang, C., Xu, J., Gao, T., Hong, X., Pan, F., Sun, F., Huang, K., Wang, D., Chen, T., & Zhang, P. (2026). Carbonation of Calcined Clay Dolomite for the Removal of Co(II): Performance and Mechanism. Journal of Xenobiotics, 16(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010013