The Effect of an Educational Intervention Program on Allied Health Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Organ Donation and Transplantation

Abstract

1. Introduction

Study Aims

- Examine the effect of an educational intervention program on allied health students’ knowledge and attitudes regarding organ donation and transplantation.

- Identify the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and knowledge and attitudes regarding organ donation and transplantation.

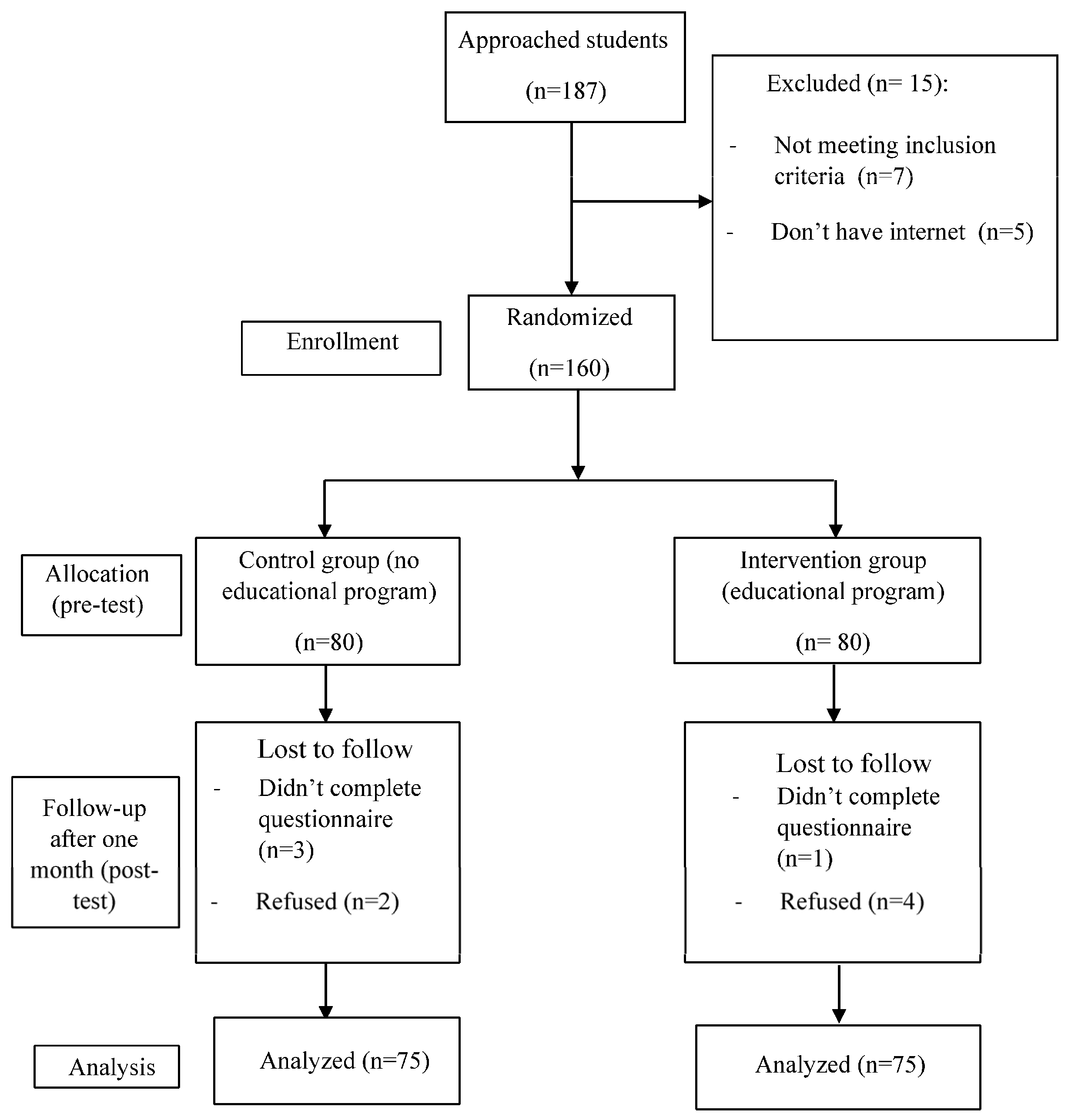

2. Methodology

2.1. Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

- ➢

- Age 18 years or older

- ➢

- Enrollment as an allied health student

- ➢

- Ability to read and understand Arabic

- ➢

- Access to the internet

- ➢

- No prior education on organ donation and transplantation

- ➢

- Willingness and ability to participate

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Collection Tools

2.5. Data Collection Procedure

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Future Perspectives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bekele, M.; Jote, W.; Workneh, T.; Worku, B. Knowledge and Attitudes about Organ Donation among Patient Companion at a Tertiary Hopsital in Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2021, 31, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindhu, A.; Ramakrishnan, T.; Khera, A.; Singh, G. A study to assess the knowledge of medical students regarding organ donation in a selected college of Western Maharashtra. Med. J. Dr DY Patil Univ. 2017, 10, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, P.K. Is presumed consent an ethically acceptable way of obtaining organs for transplant? J. Intensiv. Care Soc. 2019, 20, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, T.K.; Deo, J.; Dutt, V.; Agarwal, R.; Patel, B.B.; Ganesh, M.; More, V.K.; Pandya, K.H.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, D.; et al. Knowledge and attitude towards organ donation: A study among medical and nursing students of a medical college. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2021, 8, 5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekkodathil, A.; El-Menyar, A.; Sathian, B.; Singh, R.; Al-Thani, H. Knowledge and Willingness for Organ Donation in the Middle Eastern Region: A Meta-analysis. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 1810–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, S.; Albreizat, A.H. Living-donor organ donation: Impact of expansion of genetic relationship. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2019, 17, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation. Summary. 2023. Available online: https://www.transplant-observatory.org/summary/ (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Bas-Sarmiento, P.; Coronil-Espinosa, S.; Poza-Méndez, M.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, M. Intervention programme to improve knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour of nursing students towards organ donation and transplantation: A randomised controlled trial. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 68, 103596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaudier, M.; Binois, Y.; Dumas, F.; Lamhaut, L.; Beganton, F.; Jost, D.; Charpentier, J.; Lesieur, O.; Marijon, E.; Jouven, X.; et al. Organ donation after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A population-based study of data from the Paris Sudden Death Expertise Center. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2022, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulania, A.; Sachdeva, S.; Jha, D.; Kaur, G.; Sachdeva, R. Organ donation and transplantation: An updated overview. MAMC J. Med. Sci. 2016, 2, 18. [Google Scholar]

- The Division of Transplantation. Organ Donation Statistics. 2023. Available online: https://www.organdonor.gov/learn/organ-donation-statistics (accessed on 26 December 2023).

- Al Shaikh, A.F.; Abu Zaid, A.K.; Khader, Y. Attitudes of university students in Jordan University of Science and Technology toward organ donation and their willingness to donate (2011). Jordan Med. J. 2015, 49, 37–43. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283755490_Attitudes_of_University_Students_in_Jordan_University_of_Science_and_Technology_toward_Organ_Donation_and_Their_Willingness_to_Donate_2011 (accessed on 26 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Abdulrazeq, F.; Matsumoto, M.M.; Zourob, M.; Al-Dobai, A.; Zeyad, K.; Marwan, N.; Qeshta, A.; Aleyani, O. Renal Data from the Arab World Barriers in Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Organ Donation among Urban Jordanian Population Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transplant. 2020, 31, 624–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otturu, B.S.; Sreedevi, A.; Aruna, M.S.; Harshitha, M. A Cross Sectional Study on Knowledge and Attitude towards Organ Donation among Medical Students. EAS J. Parasitol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 5, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, W.H.W.A.; Din, N.M.; Kuppusamy, V.; Samsuri, S.; Ropi, N.A.S.M.; Kanapathy, T.; Bahri, N.N.M.S. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Related to Organ Donation Among Healthcare Workers at University of Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre (UKMMC). Bali Med. J. 2023, 12, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwahaibi, N.; Al Wahaibi, A.; Al Abri, M. Knowledge and attitude about organ donation and transplantation among Omani university students. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1115531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani Hani, A.; Bsisu, I.; Shatarat, A.; Sarhan, O.; Hassouneh, A.; Abu Alhuda, R.; Sa’adeh, A.; Alsmady, M.; Abu Abeeleh, M. Attitudes of Middle Eastern Societies towards Organ Donation: The Effect of Demographic Factors among Jordanian Adults. Res. Health Sci. 2019, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, G.A.; Garcia, V.D.; De Souza, R.L.; Franke, C.A.; Vieira, K.D.; Birckholz, V.R.Z.; Machado, M.C.; de Almeida, E.R.B.; Machado, F.O.; da Costa Sardinha, L.A.; et al. Guidelines for the assessment and acceptance of potential brain-dead organ donors. Rev. Bras. Ter. Intensiv. 2016, 28, 220–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, D. Assessment of Knowledge and Attitude Regarding Organ Donation among Care Givers of Patient. Pondicherry J. Nurs. 2012, 11, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.; Ter Goon, D.; Mtise, T.; Oladimeji, O. A Cross-Sectional Study of Professional Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Organ Donation in Critical Care Units of Public and Private Hospitals in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, P.P.; Boudville, N.; Garg, A.X. Living kidney donation: Outcomes, ethics, and uncertainty. Lancet 2015, 385, 2003–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Ko, J.W.; Park, M.R. Hospital Nurses’ Knowledge and Attitude toward Brain-dead Organ Donation. Int. J. Bio-Sci. Bio-Technol. 2016, 8, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girlanda, R. Deceased organ donation for transplantation: Challenges and opportunities. World J. Transplant. 2016, 6, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.; Zameel, A.; Aisabi, K.A.; Kumar, D.; Sujesh, P.K. Knowledge and attitude towards organ donation among people seeking health care in Kozhikode, Kerala, India. Trop. J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2019, 5, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayamol, T.R. Knowledge and Attitude towards Organ Donation among Medical Students of a Government Medical College in Northern Kerala. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Res. 2020, 8, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajadhyaksha, A.; Dias, A.; Savoiverekar, S.; Sukhtankar, A.; Shah, D.; Manerkar, G.; Kerkar, P.; Naik, S.; Dias, L. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices toward Organ Donation and Transplantation among the General Population of India: A Community-Based Study. Int. J. Sci. Study 2023, 11, 50–60. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/gim/resource/ru/sea-235313?lang=en (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Kashmir, S.; Khan, F. Attitude and Knowledge toward Organ Donation among Arts and Science Students. Indian J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 2020, 14, 402. [Google Scholar]

- Calikoglu, E.O. Knowledge and Attitudes of Intensive Care Nurses on Organ Donation. Eurasian J. Med. Oncol. 2018, 2, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbu, B.; Basnet, S.; Silwal, S. Knowledge and Attitude on Organ Donation among Nursing Students of a College in Biratnagar. Eur. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 1, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadurg, U.Y.; Gupta, A. Impact of an educational intervention on increasing the knowledge and changing the attitude and beliefs towards organ donation among medical students. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoña, B.E.; Padilla, B.S.; Macapagal, M.E.J.; Lukban, G.J. Knowledge and Attitude towards Organ Donation among Driver’s License Applicants in Metro Manila, Philippines. Health Sci. J. 2021, 15, 1–7. Available online: https://www.itmedicalteam.pl/articles/knowledge-and-attitude-towards-organ-donation-among-drivers-licenseapplicants-in-metro-manila-philippines.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Srinivasula, S.; Srilatha, A.; Doshi, D.; Reddy, B.S.; Kulkarni, S. Influence of health education on knowledge, attitude, and practices toward organ donation among dental students. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radunz, S.; Benkö, T.; Stern, S.; Saner, F.H.; Paul, A.; Kaiser, G.M. Medical students’ education on organ donation and its evaluation during six consecutive years: Results of a voluntary, anonymous educational intervention study. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2015, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibaba, F.K.; Goro, K.K.; Wolide, A.D.; Fufa, F.G.; Garedow, A.W.; Tufa, B.E.; Bobasa, E.M. Knowledge, attitude and willingness to donate organ among medical students of Jimma University, Jimma Ethiopia: Cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, T.; Takasi, P. Nursing students’ knowledge and related factors towards organ donation: A systematic review. J. Nurs. Rep. Clin. Pract. 2024, 2, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Breakwell, R. What factors influence a family’s decision to agree to organ donation? A critical literature review. Lond. J. Prim. Care 2018, 10, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruta, F.; Ferrara, P.; Terzoni, S.; Dal Mas, F.; Bottazzi, A.; Prendi, E.; Dragusha, P.; Poggi, A.D.; Cobianchi, L. The attitude towards organ donation: Differences between students of medicine and nursing. A preliminary study at Unizkm-Catholic University “Our Lady of Good Counsel” of Tirana. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 109, 105208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruta, F.; Somma, C.M.; Lusignani, M.; Vitobello, G.; Gesualdo, L.; Mas, F.D.; Peloso, A.; Cobianchi, L. The healthcare professionals’ support towards organ donation. An analysis of current practices, predictors, and consent rates in Apulian hospitals. Ann. Dell’istituto Super. Di Sanità 2021, 57, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poreddi, V.; Katyayani, B.V.; Gandhi, S.; Thimmaiah, R.; Badamath, S. Attitudes, Knowledge, and Willingness to Donate Organs among Indian Nursing Students. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transplant. 2016, 27, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adithyan, G.; Mariappan, M.; Nayana, K. A study on knowledge and attitude about organ donation among medical students in Kerala. Indian J. Transplant. 2017, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetharaman, R.V.; Rane, J.R.; Dingre, N.S. Assessment of knowledge and attitudes regarding organ donation among doctors and students of a tertiary care hospital. Artif. Organs 2021, 45, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, E.; Jenkins, K.; Rainey, M.; Tennyson, C. Knowledge Deficit of Patients Regarding Organ Donation in the Primary Healthcare Setting; Clinical Research Project; Mississippi University for Women: Columbus, MS, USA, 2020; Available online: https://athenacommons.muw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1268&context=msn-projects (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Martínez-Alarcón, L.; Ríos, A.; Gutiérrez, P.R.; Santainés-Borredá, E.; Gómez, F.J.; Agras-Suarez, M.C.; Iriarte, J.; la Fuente, G.A.C.-D.; Herruzo, R.; Hurtado-Pardos, B.; et al. Exploring Health Science Students’ Notions on Organ Donation and Transplantation: A Multicenter Study. Transplant. Proc. 2020, 52, 1428–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Alarcón, L.; Ríos, A.; Santainés-Borredá, E.; Agras-Suarez, M.C.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Hurtado-Pardos, B.; Bárcena-Calvo, C.; Perelló-Campaner, C.; Arribas-Marin, J.M.; García-Mayor, S.; et al. Nursing Students’ Knowledge About Organ Donation and Transplantation: A Spanish Multicenter Study. Transplant. Proc. 2019, 51, 3008–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardavessis, T.; Xenophontos, P.; Haidich, A.B.; Kiritsi, M.; Vayionas, M.A. Knowledge, attitudes and proposals of medical students concerning transplantations in Greece. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 2, 164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chakradhar, K.; Doshi, D.; Reddy, B.S.; Kulkarni, S.; Reddy, M.P.; Reddy, S.S. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding organ donation among Indian dental students. Int. J. Organ Transplant. Med. 2016, 7, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coad, L.; Carter, N.; Ling, J. Attitudes of young adults from the UK towards organ donation and transplantation. Transplant. Res. 2013, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.K.Y.; Ng, C.W.K.; Li, J.Y.C.; Sum, K.C.Y.; Adams, H.Y.M.; Chan, S.P.C.; Cheung, J.Y.M.; Yu, K.P.T.; Tang, B.Y.H.; Lee, P.P.W. Attitudes, knowledge, and actions with regard to organ donation among Hong Kong medical students. Hong Kong Med. J. 2008, 14, 278. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Hopewell, S.; Schulz, K.F.; Montori, V.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Devereaux, P.J.; Elbourne, D.; Egger, M.; Altman, D.G. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int. J. Surg. 2012, 10, 28–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydzewska-Rosołowska, A.; Jamiołkowska, M.; Kakareko, K.; Naumnik, B.; Zbroch, E.; Hryszko, T. Medical Students’ Attitude Toward Organ Donation in a Single Medical University. Transplant. Proc. 2020, 52, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayin, Y.Y.; Dağci, M. Attitude, Knowledge and Donor Card Volunteering of Nursing Students Regarding Organ Donation. Bezmialem Sci. 2022, 10, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordin, Y.S.; Söylemez, B.A.; Deveci, Z.; Kankaya, E.A.; Çelik, B.; Yasak, K.; Bilik, Ö.; İntepeler, Ş.S.; Duğral, E. Increasing university students attitudes towards organ donation with peer learning approach. J. Basic Clin. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kaur, K.; Saini, R.S.; Singh, S.; Aggarwal, H.K.; Chandra, H. Impact of Structured Training Program about Cadaver Organ Donation and Transplantation on Knowledge and Perception of Nursing Students at Public and Private Nursing Teaching Institute of Northern India—An Interventional Study. Indian J. Community Med. 2023, 48, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenaart, E.; Crutzen, R.; Candel, M.J.J.M.; De Vries, N.K. The effectiveness of an interactive organ donation education intervention for Dutch lower-educated students: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials 2019, 20, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocchi, L.; Petrucci, C.; Calzetta, M.A.; Dante, A.; Curcio, F.; Lancia, L.; Gonzalez, C.I.A. Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Organ Donation and Transplantation Among Nursing Students: A Multicentre Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, L.; Mishra, S.; Agrawal, M.; Shah, D. Impact of single classroom-based peer-led organ donation education exposure on high-school students and their families. Indian J. Transplant. 2019, 13, 267. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Grewal, M.; Kaur, A.; Chopra, Y.; Bhatt, A.; Choden, T.; Sharma, M. Methodical Learning on Organ Donation: Effect on Students Knowledge and Attitude. Med.-Leg. Update 2021, 21, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.T.W.; Chung, P.P.W.; Hui, Y.L.; Choi, H.C.; Lam, H.W.; Sin, L.L.; Law, C.S.; Yan, N.Y.; Choi, K.Y.; Wan, E.Y.F. Knowledge and attitude regarding organ donation among medical students in Hong Kong: A cross-sectional study. Postgrad. Med. J. 2023, 99, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, R.; Yasawy, M.; Harthi, A.; Bokhari, A.; Alabdali, A.; Alzaidi, M.; Almishal, S. Knowledge and attitude among medical students regarding organ donation in the western region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Med. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 4, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwesmi, M.B.; Alharbi, A.I.; Alsaiari, A.A.; Abu Alreesh, A.E.; Alasmari, B.A.; Alanazi, M.A.; Alanizi, M.K.; Alsaif, N.M.; Alanazi, R.M.; Alshdayed, S.A.; et al. The Role of Knowledge on Nursing Students’ Attitudes toward Organ Donation: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanholder, R.; Domínguez-Gil, B.; Busic, M.; Cortez-Pinto, H.; Craig, J.C.; Jager, K.J.; Mahillo, B.; Stel, V.S.; Valentin, M.O.; Zoccali, C.; et al. Organ donation and transplantation: A multi-stakeholder call to action. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Lin, L.; Xu, X.; He, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Lei, L.; Luo, Y.; Deng, J.; Yi, D. Qualitative Analysis of Factors That Hinder Intensive Care Unit Nurses in Western China from Encouraging Patients to Donate Organs. Transplant. Proc. 2020, 52, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intervention Group (n = 75) | Control Group (n = 75) | Both Groups (n = 150) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M (SD) | N (%) | M (SD) | N (%) | M (SD) | N (%) |

| Age | 21.1 (2.89) | 20.8 (1.94) | 20.9 (2.46) | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| - Male | 19 (25.3) | 18 (24) | 37 (24.7) | |||

| - Female | 56 (74.7) | 57 (76.0) | 113 (75.3) | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| - Single | 69 (92) | 138 (92) | ||||

| - Married | 3 (4) | 69 (92) | 9 (6) | |||

| - Divorced | 2 (2.7) | 6 (8) | 2 (1.3) | |||

| - Widow | 1(1.3) | 1 (0.7) | ||||

| Academic program | ||||||

| - Pharmacy | 21 (28) | 11 (14.7) | 32 (21.3) | |||

| - Nursing | 41 (54.7) | 42 (56) | 83 (55.3) | |||

| - Midwifery | 13 (17.3) | 22 (29.3) | 35 (23.3) | |||

| Academic year | ||||||

| - First year | 5 (6.7) | 8 (10.7) | 13 (8.7) | |||

| - Second year | 65 (86.7) | 56 (74.7) | 121 (80.7) | |||

| - Third year | 5 (6.7%) | 11 (14.7) | 16 (10.7) | |||

| GPA | 77.8 (74.6) | 69.8 (8.0) | 73.8 (53) | |||

| Residency | ||||||

| - Town | 73 (97.3) | 70 (93.3) | 143 (95.3) | |||

| - Rural | 2 (2.3%) | 5 (6.7) | 7 (4.7) | |||

| Smoking | ||||||

| - Yes | 13 (17.3) | 16 (21.3) | 29 (19.3) | |||

| - No | 62 (82.7) | 59 (78.7) | 121 (80.7) | |||

| Mother education | ||||||

| - Illiterate | 6 (8) | 2 (2.7) | 8 (5.3) | |||

| - Primary | 7 (9.3) | 4 (5.3) | 11 (7.3) | |||

| - High school | 35 (46.7) | 35 (46.7) | 70 (46.7) | |||

| - Diploma | 16 (21.3) | 22 (29.3) | 38 (25.3) | |||

| - BSC | 9 (12) | 11 (14.7) | 20 (13.3) | |||

| - Master’s degree or higher | 2 (2.7) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (2) | |||

| Father Education | ||||||

| - Illiterate | 5 (6.7) | 6 (8) | 11 (7.3) | |||

| - Primary | 7 (9.3) | 4 (5.3) | 11 (7.3) | |||

| - High school | 38 (50.7) | 43 (57.3) | 81 (54) | |||

| - Diploma | 8 (10.7) | 12 (16) | 20 (13.3) | |||

| - BSC | 10 (13.3) | 8 (10.7) | 18 (12) | |||

| - Master’s degree or higher | 7 (9.3) | 2 (2.7) | 9 (6) | |||

| Test Score | Intervention Group (n = 75) M (SD) | Control Group (n = 75) M (SD) | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test knowledge and attitudes score | 38.61 (3.14) | 40.21 (2.40) | 1.96 |

| Post-test knowledge and attitudes score | 41.09 (2.57) | 40.29 (2.40) | −3.49 *** |

| Age | GPA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge and attitudesscore Intervention group (n = 75) | rs | 0.011 | 0.073 |

| Variable | N (%) | Knowledge and Attitudes Score M (SD) | Test Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | t = −0.079 | ||

| - Male | 19 (25.3%) | 41.05 (2.27) | |

| - Female | 56 (74.7%) | 41.10 (2.69) | |

| Residency | t = 0.052 | ||

| - Town | 73 (97.3%) | 41.09 (2.56) | |

| - Rural | 2 (2.3%) | 41 (4.24) | |

| Smoking | t = −0.445 | ||

| - Yes | 13 (17.3%) | 41.38 (2.98) | |

| - No | 62 (82.7%) | 41.03 (2.50) |

| Variable | N (%) | Knowledge and Attitudes Score M (SD) | Test Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | F = 1.271 | ||

| - Single | 69 (92%) | 41.15 (2.61) | |

| - Married | 3 (4%) | 39 (1.0) | |

| - Divorced | 2 (2.7%) | 43 (1.41) | |

| - Widow | 1 (1.3%) | 39 | |

| Academic program | F = 0.193 | ||

| - Pharmacy | 21 (28%) | 40.80 (2.99) | |

| - Nursing | 41 (24.7%) | 41.24 (2.44) | |

| - Midwifery | 13 (17.3%) | 41.07 (2.43) | |

| Academic year | F = 1.729 | ||

| - First year | 5 (6.7%) | 43 (1) | |

| - Second year | 65 (86.7%) | 41 (2.5) | |

| - Third year | 5 (6.7%) | 40.2 (3.3) | |

| Mother education | F = 0.417 | ||

| - Illiterate | 6 (8%) | 41.1 (2.63) | |

| - Primary | 7 (9.3%) | 41.4 (1.90) | |

| - Secondary | 35 (46.7%) | 41 (2.62) | |

| - Diploma | 16 (21.3%) | 40.7 (3.10) | |

| - BSC | 9 (12%) | 41.1 (2.26) | |

| - Master’s degree or higher | 2 (2.7%) | 43 (0.70) | |

| Father Education | F = 0.213 | ||

| - Illiterate | 5 (6.7%) | 41 (3.39) | |

| - Primary | 7 (9.3%) | 41.5 (1.71) | |

| - Secondary | 38 (50.7%) | 41 (2.86) | |

| - Diploma | 8 (10.7%) | 41.6 (1.99) | |

| - BSC | 10 (13.3%) | 40.5 (2.22) | |

| - Master’s degree or higher | 7 (9.3%) | 41 (2.57) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hamdan, F.; Alfarajat, L.; Alnjadat, R.; Almomani, E.; Etoom, M.; AbuAlrub, S. The Effect of an Educational Intervention Program on Allied Health Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Organ Donation and Transplantation. Nurs. Rep. 2026, 16, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep16010015

Hamdan F, Alfarajat L, Alnjadat R, Almomani E, Etoom M, AbuAlrub S. The Effect of an Educational Intervention Program on Allied Health Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Organ Donation and Transplantation. Nursing Reports. 2026; 16(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep16010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamdan, Falastine, Loai Alfarajat, Rafi Alnjadat, Eshraq Almomani, Mohammad Etoom, and Salwa AbuAlrub. 2026. "The Effect of an Educational Intervention Program on Allied Health Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Organ Donation and Transplantation" Nursing Reports 16, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep16010015

APA StyleHamdan, F., Alfarajat, L., Alnjadat, R., Almomani, E., Etoom, M., & AbuAlrub, S. (2026). The Effect of an Educational Intervention Program on Allied Health Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Organ Donation and Transplantation. Nursing Reports, 16(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep16010015