Nurses’ Experience Using Telehealth in the Follow-Up Care of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Telehealth

1.2. Research on Telehealth

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Defining the Review Question

2.2. Developing the Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Screening and Selecting the Sources of Evidence

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Analysing the Evidence and Summarizing the Findings

3. Results

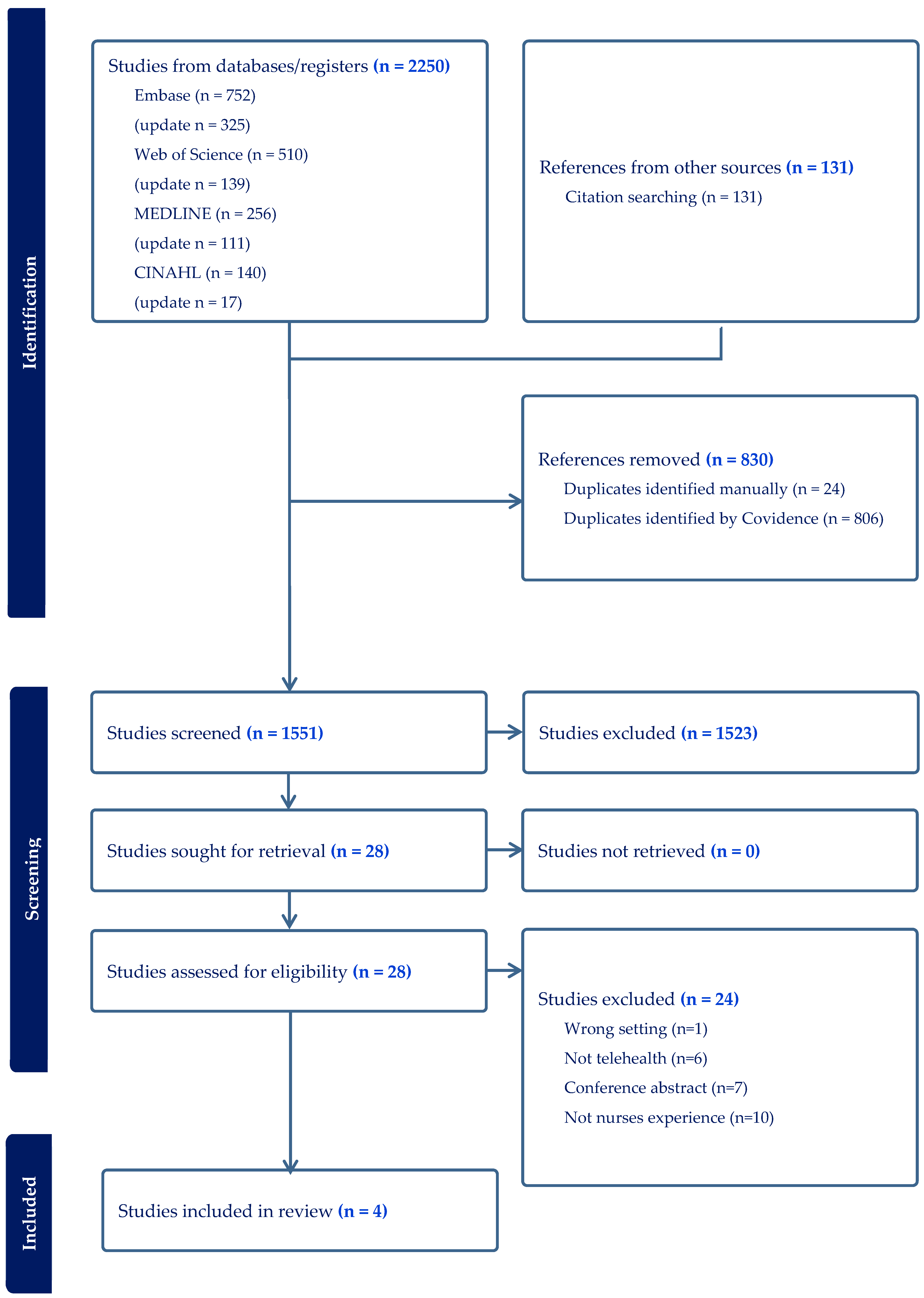

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Nurses’ Experience on Performing Telehealth

3.3.1. Benefits

- The Vital Contributions of IBD telenursing in Empowering Patients by Bridging Health Literacy and Self-Care skills

- Optimal use of staffing time supports patient-centred care

- Ease of use

3.3.2. Barriers

- Increased workload and task imbalance

- The need for customized interventions

- Technical issues and concerns regarding the security of the digital system

- Telehealth; a supplementary option or a standard procedure

- Concerns related to the patient–nurse relationship

4. Discussion

4.1. Nurses’ Experiences on Benefits Conducting Telehealth

4.2. Nurses Experiences on Barriers Conducting Telehealth

4.3. Strenghts and Limitations

4.4. Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD | Crohn’s Disease |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| MD | Doctor of Medicine |

| PCC | Population, Concept, Context |

| PRESS | Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROs | Patient-Reported Outcomes |

| RN | Registered Nurse |

| UC | Ulcerative Colitis |

References

- Yin, A.L.; Hachuel, D.; Pollak, J.P.; Scherl, E.J.; Estrin, D. Digital Health Apps in the Clinical Care of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, W.Y.; Zhao, M.; Ng, S.C.; Burisch, J. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: East meets west. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 35, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, J. Epidemiology. In Inflammatory Bowel Disease Nursing Manual; Sturm, A., White, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Böhmig, M. Mechanisms of Disease, Etiology and Clinical Manifestations. In Inflammatory Bowel Disease Nursing Manual; Sturm, A., White, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fantini, M.C.; Loddo, E.; Di Petrillo, A.; Onali, S. Telemedicine in inflammatory bowel disease from its origin to the post pandemic golden age: A narrative review. Dig. Liver Dis. 2024, 56, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, U. Clinics. In Inflammatory Bowel Disease Nursing Manual; Sturm, A., White, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 453–462. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorino, G.; Allocca, M.; Chaparro, M.; Coenen, S.; Fidalgo, C.; Younge, L.; Gisbert, J.P. ‘Quality of Care’ Standards in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2018, 13, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Wu, K.; Samyue, T.; Fry, S.; Stanley, A.; Ross, A.; Malcolm, R.; Connell, W.; Wright, E.; Ding, N.S.; et al. Outcomes of a Comprehensive Specialist Inflammatory Bowel Disease Nursing Service. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30, 960–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sheikh, M.; Ankersen, D.V.; Olsen, J.; Spanggaard, M.; Peters-Lehm, C.T.; Naimi, R.M.; Bennedsen, M.; Burisch, J.; Munkholm, P. The Costs of Home Monitoring by Telemedicine vs. Standard Care for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases—A Danish Register-Based, 5-Year Follow-up Study. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2024, 19, jjae120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Martinez, I.; Atreja, A.; Sitapati, A.M.; Sandborn, W.J.; Ohno-Machado, L.; Singh, S. Digital Health Technologies for Remote Monitoring and Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Linschoten, R.C.A.; Visser, E.; Niehot, C.D.; van der Woude, C.J.; Hazelzet, J.A.; van Noord, D.; West, R.L. Systematic review: Societal cost of illness of inflammatory bowel disease is increasing due to biologics and varies between continents. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 54, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalambous, J.; Hollingdrake, O.; Currie, J. Nurse practitioner led telehealth services: A scoping review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerret, S.M.; Nuccio, S.; Compton, A.; Keegan, M.; Rapala, K. Nurses’ Experiences and Perspectives of the Telehealth Working Environment and Educational Needs. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2023, 54, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivunen, M.; Saranto, K. Nursing professionals’ experiences of the facilitators and barriers to the use of telehealth applications: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fant, C.; Adelman, D.S.; Summer, G.A. COVID-19 and telehealth: Issues facing healthcare in a pandemic. Nurse Pract. 2021, 46, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J.; Levy, D.R.; Senathirajah, Y. Defining Telehealth for Research, Implementation, and Equity. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e35037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundereng, E.D.; Nes, A.A.G.; Holmen, H.; Winger, A.; Thygesen, H.; Jøranson, N.; Borge, C.R.; Dajani, O.; Mariussen, K.L.; Steindal, S.A. Health Care Professionals’ Experiences and Perspectives on Using Telehealth for Home-based Palliative Care: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e43429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldring, T.; Smith, S.M.S. Patient-Reported Outcomes (Pros) and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (Proms). Health Serv. Insights 2013, 2013, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Huang, J.J.; Torous, J. Hybrid care in mental health: A framework for understanding care, research, and future opportunities. NPP—Digit. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2024, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakak, F.; Patel, R.N.; Gearry, R.B. Review article: Telecare in gastroenterology—Within the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, 1170–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguas, M.; Del Hoyo, J.; Vicente, R.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Melcarne, L.; Hernandez-Camba, A.; Madero, L.; Arroyo, M.T.; Sicilia, B.; Chaparro, M.; et al. Telemonitoring of Active Inflammatory Bowel Disease Using the App TECCU: Short-Term Results of a Multicenter Trial of GETECCU. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e60966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, D.S.; Fant, C.; Summer, G. COVID-19 and telehealth: Applying telehealth and telemedicine in a pandemic. Nurse Pract. 2021, 46, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson Eklund, J.; Holmström, I.K.; Kumlin, T.; Kaminsky, E.; Skoglund, K.; Höglander, J.; Sundler, A.J.; Condén, E.; Summer Meranius, M. “Same same or different?” A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oudbier, S.J.; Souget-Ruff, S.P.; Chen, B.S.J.; Ziesemer, K.A.; Meij, H.J.; Smets, E.M.A. Implementation barriers and facilitators of remote monitoring, remote consultation and digital care platforms through the eyes of healthcare professionals: A review of reviews. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e075833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravina, A.G.; Pellegrino, R.; Durante, T.; Palladino, G.; D’Onofrio, R.; Mammone, S.; Arboretto, G.; Auletta, S.; Imperio, G.; Ventura, A.; et al. Telemedicine in inflammatory bowel diseases: A new brick in the medicine of the future? World J. Methodol. 2023, 13, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, É.B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence. Reviewers. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/reviewers/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Ringnes, H.K.; Thørrisen, M.M. Scoping Review—A Systematic and Flexible Method for Knowledge Synthesis (Scoping Review—En Systematisk og Fleksibel Metode for Kunnskapsoppsummering), 1st ed.; Cappelen Damm Akademisk: Oslo, Norway, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, A.S.; Appel, C.W.; Larsen, B.F.; Hanna, L.; Kayser, L. Digital patient-reported outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease routine clinical practice: The clinician perspective. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2022, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, U.; Stitt, L.; Rohatinsky, N.; Watson, M.; Currie, B.; Westin, L.; McCaw, W.; Norton, C.; Nistor, I. Patients’ Access to Telephone and E-mail Services Provided by IBD Nurses in Canada. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2021, 5, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aintabi, D.; Greenberg, G.; Berinstein, J.A.; DeJonckheere, M.; Wray, D.; Sripada, R.K.; Saini, S.D.; Higgins, P.D.R.; Cohen-Mekelburg, S. Remote Between Visit Monitoring in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care: A Qualitative Study of CAPTURE-IBD Participants and Care Team Members. Crohn’s Colitis 360 2024, 6, otae032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidmead, E.; Marshall, A. A case study of stakeholder perceptions of patient held records: The Patients Know Best (PKB) solution. Digit. Health 2016, 2, 2055207616668431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aveyard, H. Doing a Literature Review in Health and Social Care: A Practical Guide; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hasannejadasl, H.; Roumen, C.; Smit, Y.; Dekker, A.; Fijten, R. Health Literacy and eHealth: Challenges and Strategies. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2022, 6, e2200005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhunnoo, P.; Kemp, B.; McGuigan, K.; Meskó, B.; O’Rourke, V.; McCann, M. Evaluation of Telemedicine Consultations Using Health Outcomes and User Attitudes and Experiences: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e53266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.P.; Ross, M.S.H.; Adatorwovor, R.; Wei, H. Telehealth and mobile health interventions in adults with inflammatory bowel disease: A mixed-methods systematic review. Res. Nurs. Health 2021, 44, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.J.; Manalili, K.; Jolley, R.J.; Zelinsky, S.; Quan, H.; Lu, M. How to practice person-centred care: A conceptual framework. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmanpour, N.; Salehi, A.; Nemati, S.; Rahmanian, M.; Zakeri, A.; Drissi, H.B.; Shadzi, M.R. The effect of self-care, self-efficacy, and health literacy on health-related quality of life in patients with hypertension: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Health Promotion by Social Cognitive Means. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina Martin, G.; de Mingo Fernández, E.; Jiménez Herrera, M. Nurses’ perspectives on ethical aspects of telemedicine. A scoping review. Nurs. Ethics 2024, 31, 1120–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wathne, H.; May, C.; Morken, I.M.; Storm, M.; Husebø, A.M.L. Acceptability and usability of a nurse-assisted remote patient monitoring intervention for the post-hospital follow-up of patients with long-term illness: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2024, 7, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foong, H.F.; Kyaw, B.M.; Upton, Z.; Tudor Car, L. Facilitators and barriers of using digital technology for the management of diabetic foot ulcers: A qualitative systematic review. Int. Wound J. 2020, 17, 1266–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gartz, J.; O’Rourke, J. Telehealth educational interventions in nurse practitioner education: An integrative literature review. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2021, 33, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, M.; Lever, E.; Harwood, R.; Gordon, C.; Wincup, C.; Blane, M.; Brimicombe, J.; Lanyon, P.; Howard, P.; Sutton, S.; et al. Telemedicine in rheumatology: A mixed methods study exploring acceptability, preferences and experiences among patients and clinicians. Rheumatology 2021, 61, 2262–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, A.R.; Afaf Haroush Shaman, A.-S.; Modhi Hulayyil Salem, A.; Layla Sallam, M.; Al-Shabili, A.; Dalal Sayil, A.; Nemah Ahmed, R.; Modi, N.A.; Samirah Ali Ali, M.; Layla Abdullah, A.-D. The Role of Nurse-Led Telehealth Interventions in Improving Healthcare Services and Patient Care. J. Int. Crisis Risk Commun. Res. 2024, 7, 96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Øvrebotten, C.M.; Hovland, R.T.; Låver, J.C.Ø.; Bentsen, S.B.; Moltu, C. Healthcare professionals’ perceived challenges and benefits of digital patient-reported data for in-hospital postoperative pain monitoring: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2025, 170, 105174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Population | Concept | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Perception | Web-based monitoring |

| IBD | View | Telehealth |

| Crohn Disease | Perspective | Telemedicine |

| Ulcerative Colitis | Experience | m-health/mhealth |

| Attitude | Remote Consultation | |

| Evaluation | Remote patient consultation | |

| Thoughts | E-health/ehealth | |

| Reports | Digital health | |

| Satisfaction | Digital health monitoring | |

| Opinion | Digital home monitoring | |

| Feedback | Digital care | |

| Nurse–Patient Relations | Digital home care | |

| Nurses by role | Digital needs-based follow-up | |

| Nurse-led | ||

| Nurse-managed center | ||

| Nurse clinic | ||

| Nurse managed clinic | ||

| Nurse-delivered | ||

| Attitude of health personnel |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and/or ulcerative colitis) | Other chronic diseases |

| Digital follow-up in the form of web-based platforms (asynchronous) as the only follow-up, or combined with either Synchronous real time telephone or video consultations or Physical consultation by a nurse | Standard consultation with physical consultation as the only follow-up |

| Nurses’ experiences | Patients’ experiences |

| IBD nurses (nurses and specialist nurses) alone, or as part of a team where data from nurses can be extracted | Data from doctors and other healthcare personnel |

| Follow-up of adults over 18 years of age | Follow-up of children |

| Full text available | Full text not available |

| English or Scandinavian languages | Languages other than English and Scandinavian |

| Peer-reviewed primary research articles with qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method design | Conference abstracts, editorials, grey literature, theses, all types of reviews (systematic, scoping, integrative, umbrella and narrative) |

| CINAHL | Keywords/Index Terms/Phrases |

|---|---|

| Population | “(Mesh term) Inflammatory Bowel Disease” OR “Inflammatory bowel disease*” OR “IBD” OR “(Mesh term) Crohn Disease” OR “Crohn* disease” “(Mesh term) Colitis, Ulcerative” OR “Ulcerative colitis” OR “Crohn*” AND |

| Concept | “(Mesh term) Nurse-Patient Relations’ OR “Nurse-patient relation*” OR “(Mesh term) Nurses by Role+” OR “Nurs* role*” OR “Nurse-led*” OR “(Mesh term) Nurse-Managed Centers” OR “Nurse-Managed center*” OR “Nurs* clinic*” OR “Nurs* managed*” OR “(Mesh term) Nurse Attitudes” OR “Nurs* attitude*” OR “(Mesh term) Attitude of health personnel+” OR “Attitude* N3 (personnel or staff or professional*)” OR “(Mesh term) Perception+” OR “Perception*” OR “View*” OR “Perspective*” OR “Experience*” OR “(Mesh term) Attitude+” OR “Attitude*” OR “(Mesh term) Evaluation+” OR “Evaluation*” OR “Thought*” OR “(Mesh term) Reports+” OR “Report*” OR “Satisfaction” OR “Opinion*” OR “Feedback” OR “(Mesh term) Feedback” OR “Nurse delivered” AND |

| Context | “Web-based monitoring” OR “(Mesh term) Internet-based intervention” OR “Internet-based intervention” OR “(Mesh term) Telehealth+” OR “Telehealth” OR “(Mesh term) Telemedicine+” OR “Telemedicine” OR “Mhealth” OR “m-health” OR “(Mesh term) Remote Consultation” OR “remote consultation*” OR “remote patient monitoring” OR “ehealth” OR “e-health” OR “(Mesh term) Digital Health+” OR “Digital health*” OR “Digital Health monitoring” OR “Digital care*” |

| First Author, Year, Country | Aim | Setting | Participants | Digital Platform | Context of Telehealth | Methods (Design, Data Collection Method, Data Analysis) | Data Collection Period | Key Findings: Benefits | Key Findings: Barriers | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amalie Søgaard Nielsen, 2022, Denmark. [34] | To explore hospital clinicians’ attitudes and rationales towards digital PROs used in the basic care of IBD. | Outpatient IBD clinic providing care to 850 patients with IBD. | Six RNs and six MDs. | Digital PRO platform called AmbuFlex IBD. | Hybrid. Asynchronous combined with in-person consultations or phone calls. | Action research, qualitative semi-structured face-to-face interviews, thematic analysis. | October 1st to December 20th, 2018. | Empower patients and boost their health literacy. Better prepared to consultations. Enhance two-way communication. Increase accessibility to healthcare. Timely monitoring. Improve quality of care due to more reliable real time data. More focus on issues worrying patients. Optimal use of staff by reducing consultation time with healthy patients. Ease of use. | Time consuming to manage and coordinate the digital PRO system. Redistributed care from MDs to RNs. Question overload in the PRO questionnaires. Technology challenges. Patient engagement variability. Clinicians’ attitudes. Patient–nurse relationship. | Digital PROs are useful tools to prioritise resources and prevent avoidable face-to-face consultations. Digital PRO-based follow up is recommended being initiated when a relationship is established. |

| Usha Chauhan, 2021, Canada. [35] | To capture utilization of phone and e-mail services among Canadian IBD nurses for 14 days. | Academic centres and community centres. | Twenty-one IBD nurses from 16 centres across Canada. 572 patients nurse encounters were reported. | E-mail communication. | Hybrid. Asynchronous and synchronous (telephone and email). | Cross-sectional, survey with 8 questions, statistical analyses. | Between 1 May 2017 and 30 June 2017. | Improved access to care and continuity of nursing care. Timely monitoring. Optimal use of staff time avoiding unnecessary clinic visits and calls to gastroenterologists. User-friendly. | Increased workload as RNs manage numerous calls that could have been handled by non-nursing staff, such as scheduling appointments, addressing insurance and financial concerns. Absence of in-person interaction. | Nurses were able to address 61% of IBD patients’ concerns independently, helping patients avoid contacting other health services. |

| Daniel Aintabi, 2024, USA. [36] | To evaluate the perspective on CAPTURE-IBD from a patient and clinician perspective, and perspective on care coordinator-triggered algorithms. | A gastro-enterology clinic at a tertiary referral centre. | Two nurses, two gastroenterologists, and the CAPTURE-IBD care coordinator. | Digital PRO platform called CAPTURE-IBD. | Asynchronous. | Qualitative, individual face-to-face interviews, rapid qualitative analysis. | Between April 2019 and January 2020. | Support symptom monitoring and psychosocial care. Support action plans between visits. User-friendly. Enhance patient engagement and improve communication. | Increase nursing workload. Should better capture day-to-day changes in patients with comorbid conditions. Need for clearer action plans guided by patient-reported outcomes. | Remote PRO monitoring is valuable, allowing for more frequent assessments in patients with active IBD and less frequent monitoring for those with inactive IBD. Increased workload issues need to be addressed in PRO-guided care pathways to be sustainable. |

| Elaine Bidmead, 2016, UK. [37] | To understand the barriers and benefits from using the PKB-PHR system and share the findings. | Gastro-enterology department of an English NHS foundation trust hospital. | Three IBD nurse specialists. | Patient-held personal health records (PHRs) called Patients Know Best (PKB). | Asynchronous. | Case study, semi-structured individual telephone interviews, thematic analysis. | Between January and February 2015. | Empower patients by increasing confidence and self-management. Enhance two-way communication. Improve access to care. Timely monitoring. Optimal use of staff time. Cost effective. Easier to use after initial start-up. | Technical challenges. Need for adequate training. Fear of more work. Clinicians attitude. Data security concerns. Problems with data integration. Variability in patient engagement. | The PKB system helps nurses in empowering patients by creating streamlined pathways for stable IBD patients to access information and proactive support, resulting in greater patient confidence, ownership of their condition, adherence to medication regimens, and enhanced self-management. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sæterøy-Hansen, N.K.; Reime, M.H. Nurses’ Experience Using Telehealth in the Follow-Up Care of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—A Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2026, 16, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep16010011

Sæterøy-Hansen NK, Reime MH. Nurses’ Experience Using Telehealth in the Follow-Up Care of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports. 2026; 16(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep16010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleSæterøy-Hansen, Nanda Kristin, and Marit Hegg Reime. 2026. "Nurses’ Experience Using Telehealth in the Follow-Up Care of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—A Scoping Review" Nursing Reports 16, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep16010011

APA StyleSæterøy-Hansen, N. K., & Reime, M. H. (2026). Nurses’ Experience Using Telehealth in the Follow-Up Care of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports, 16(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep16010011