Instruments for Assessing Nursing Care Quality: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Review Question

- Clinical contexts: in which healthcare settings (e.g., hospital wards, community care, specialized units) have QNC assessment instruments been developed, adapted, or implemented?

- Instrument characteristics: what are the structural, conceptual, and methodological features of these instruments, including format, length, target respondents, and theoretical concepts?

- Domains of nursing care quality: which dimensions of nursing care quality (e.g., technical competence, interpersonal relationships, patient-centeredness, holistic care) are captured by these instruments?

- Psychometric properties: what evidence exists regarding the reliability, validity, and overall measurement robustness of these instruments, including cross-cultural adaptations and longitudinal evaluations?

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.3.1. Participants

2.3.2. Concept

2.3.3. Context

2.3.4. Types of Sources

- Primary empirical studies, both quantitative and qualitative;

- Studies focused on instrument development or validation;

- Studies involving translation and cross-cultural adaptation instruments;

- Gray literature, such as dissertations.

- Studies that describe, validate, apply, or adapt instruments to assess the quality of nursing care.

- Publications available in English, Portuguese, or Spanish.

- Studies providing sufficient methodological detail to evaluate the instrument and its domains.

- Instruments focused solely on individual nursing competencies (e.g., technical skills or proficiency) without addressing broader aspects of care quality.

- Theoretical works lacking empirical testing or practical application.

- Studies where nurses were not a primary respondent group for the instrument.

2.4. Search Strategy

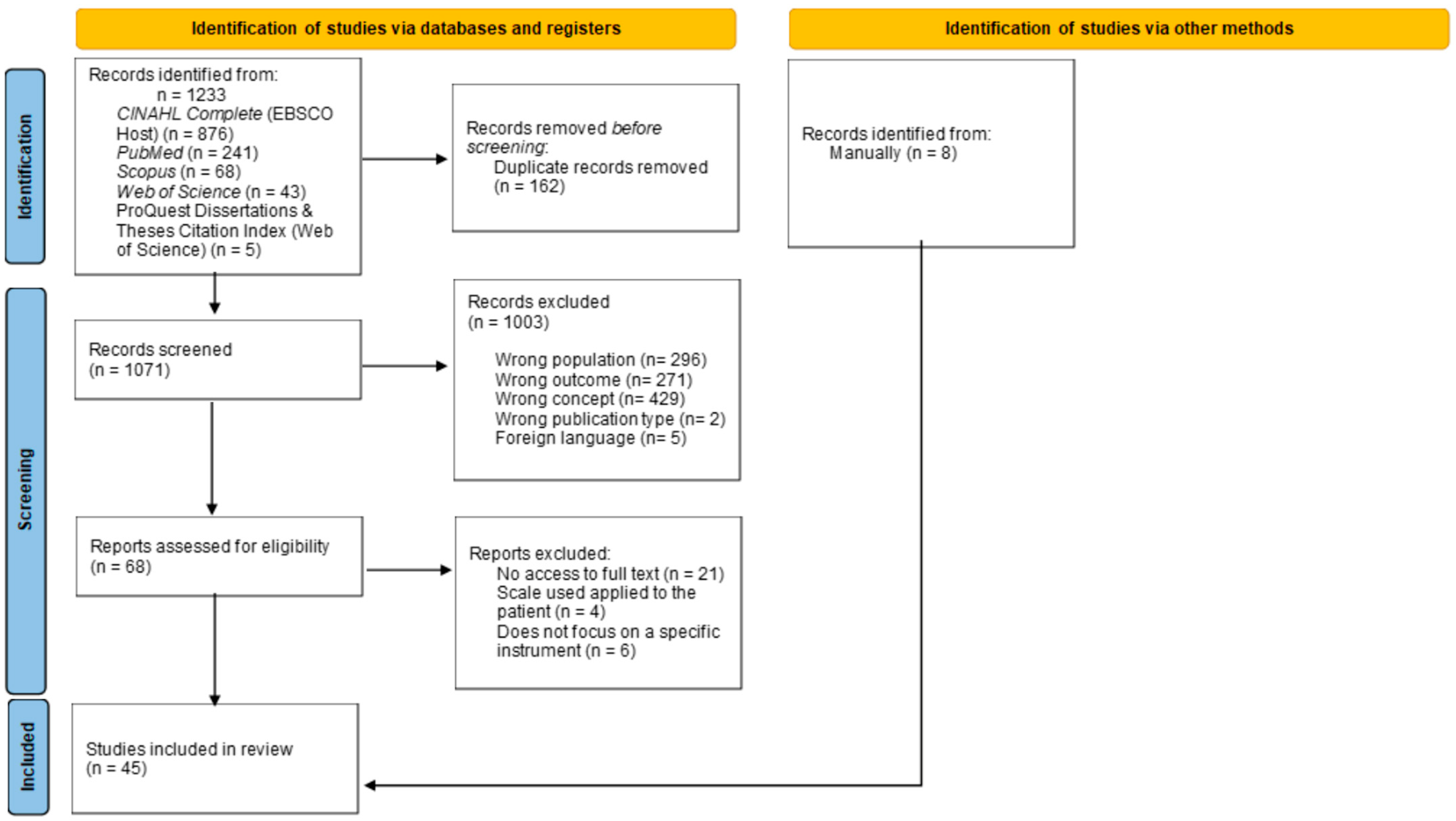

2.5. Study Selection

2.6. Data Extracion

- Authors, year, and country;

- Study objective;

- Name and type of instrument;

- Conceptual definition of quality;

- Clinical context of application;

- Domains and dimensions assessed;

- Psychometric properties (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha, construct validity, test–retest reliability);

- Summary of main findings.

2.7. Data Analysis and Presentation

3. Results

3.1. Overall Characterization of the Studies

3.2. Definition of Quality of Care and Related Factors

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

3.3. Context of Studies

3.4. Psychometric Properties

3.5. Instrinsic Instrument Limitations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sloane, D.M.; Smith, H.L.; McHugh, M.D.; Aiken, L.H. Effect of changes in hospital nursing resources on improvements in patient safety and quality of care: A panel study. Med. Care 2018, 56, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, E.; Stolt, M.; Salminen, L.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Use of the Good Nursing Care Scale: A systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 81, e12567. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, J.; Malliaris, A.P.; Bakerjian, D. Nursing and Patient Safety. PSNet [Internet]. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health & Human Services. 2021. Available online: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/nursing-and-patient-safety (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- McHugh, M.D.; Ma, C.; Jiang, T.; Harless, D.W. Nurse staffing and hospital quality of care: Evidence from nurse staffing regulation in New Jersey. Health Serv. Res. 2021, 56, 471–481. [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Ora, C.; Ball, J.; Reinius, M.; Griffiths, P. Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 113, 103788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. The quality of care: How can it be assessed? JAMA 1988, 260, 1743–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Maqbali, M. Quality of nursing care: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2024, 30, e13123. [Google Scholar]

- Koy, V.; Yunibhand, J.; Angsuroch, Y. A systematic review of nursing care quality indicators for low- and middle-income countries. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2016, 48, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Burhans, L.M.; Alligood, M.R. Quality nursing care in the words of nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 1689–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfern, S.J.; Norman, I.J. Quality assessment instruments in nursing: Towards validation. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 1995, 32, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, I.J.; Redfern, S.J. The validity of two quality assessment instruments: Monitor and Senior Monitor. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 1996, 33, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrayyan, M.T. Jordanian nurses’ job satisfaction, patients’ satisfaction and quality of nursing care. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2006, 53, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.A.; Yom, Y.H. A comparative study of patients’ and nurses’ perceptions of the quality of nursing services, satisfaction and intent to revisit the hospital: A questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, I.S.; Lindgren, M. The Karen instruments for measuring quality of nursing care. Item analysis. Vård I Nord. 2008, 89, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.H.; Akkadechanunt, T.; Xue, X.L. Quality nursing care as perceived by nurses and patients in a Chinese hospital. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 1722–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, B.; Fontanaud, N.; Pronost, A.M. Effect of using an instrument for continuous evaluation of nursing quality in terms of employment satisfaction and of their affective implications. Rech. Soins Infirm. 2010, 102, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmez, Y.C.; Ozbayir, T. Validity and reliability of the ‘Good Perioperative Nursing Care Scale’ for Turkish patients and nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, M.; Andersson, I.S. The Karen instruments for measuring quality of nursing care: Construct validity and internal consistency. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2011, 23, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, D.D.; Rosenberg, M.C.; Kovner, C.T.; Brewer, C. Early career RNs’ perceptions of quality care in the hospital setting. Qual. Health Res. 2011, 21, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Hauck, Y.; Bremner, A.; Finn, J. Quality nursing care in Australian paediatric hospitals: A Delphi approach to identifying indicators. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 1594–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bogaert, P.; Kowalski, C.; Weeks, S.M.; Van Heusden, D.; Clarke, S.P. The relationship between nurse practice environment, nurse work characteristics, burnout and job outcome and quality of nursing care: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 1667–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Lindholm, M.; Pettersson, M. Perceptions of nursing care quality, in acute hospital settings measured by the Karen instruments. J. Nurs. Manag. 2013, 21, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charalambous, A.; Adamakidou, T. Construction and validation of the Quality of Oncology Nursing Care Scale (QONCS): Development of a tool to assess patients’ perceptions of oncology nursing care. BMC Nurs. 2014, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossaneis, M.A.; Gabriel, C.S.; Haddad, M.C.F.; Melo, M.R.A.; Bernardes, A. Indicadores de qualidade utilizados nos serviços de enfermagem de hospitais de ensino. Rev. Eletr. Enferm. 2014, 16, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyce, J.; Gouveia, M.J.B.; Medinas, M.A.; Santos, A.S.; Ferreira, R.F. A Donabedian model of the quality of nursing care from nurses’ perspectives in a Portuguese hospital: A pilot study. J. Nurs. Meas. 2015, 23, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koy, V.; Yunibhand, J.; Angsuroch, Y. The quantitative measurement of nursing care quality: A systematic review of available instruments. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2016, 63, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, M.M.F.P.S.; Gonçalves, M.N.C.; Ribeiro, O.M.P.L.; Tronchin, D.M.R. Quality of nursing care: Instrument development and validation. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2016, 69, 864–870. [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger, H.K.; Zhu, J.; Read, E. New nurses’ perceptions of professional practice behaviours, quality of care, job satisfaction and career retention: A structural equation modelling approach. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcântara-Garzin, A.C.; Melleiro, M.M. The quality of nursing care in diagnostic medicine: Construction and validation of an instrument. Aquichan 2017, 17, 162–170. [Google Scholar]

- Koy, V.; Yunibhand, J.; Angsuroch, Y.; Turale, S. Development and psychometric testing of the Cambodian Nursing Care Quality Scale. Pac. Rim. Int. J. Nurs. Res. 2017, 21, 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, O.M.P.L.; Martins, M.M.F.P.S.; Tronchin, D.M.R. Nursing care quality: A study carried out in Portuguese hospitals. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2017, 4, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsyouf, W.S.; Hamdan-Mansour, A.M.; Hamaideh, S.H.; Alnadi, K.M. Nurses’ and patients’ perceptions of the quality of psychiatric nursing care in Jordan. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2018, 32, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaalan, K.; Kunaviktikul, W.; Akkadechanunt, T.; Wichaikhum, O.A.; Turale, S. Factors predicting quality of nursing care among nurses in tertiary care hospitals in Mongolia. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2019, 66, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolt, M.; Katajisto, J.; Kottorp, A.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Measuring quality of care: A Rasch validity analysis of the Good Nursing Care Scale. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2019, 34, E1–E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulueta Egea, M.; Prieto-Ursúa, M.; Bermejo Toro, L. Good palliative nursing care: Design and validation of the Palliative Nursing Care Quality Scale (PNCQS). J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 2757–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsogbadrakh, B.; Kunaviktikul, W.; Akkadechanunt, T.; Wichaikhum, O.A.; Gaalan, K.; Badamdorj, O.; Stark, A. Development and psychometric testing of the Quality Nursing Care Scale in Mongolia. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, Ø.L.; Skundberg-Kletthagen, H.; Lundquist, L.-O.; Gonzalez, M.T.; Schröder, A. The relationships between health professionals’ perceived quality of care, family involvement and sense of coherence in community mental health services. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 42, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Aungsuroch, Y.; Gunawan, J.; Sha, L.; Shi, T. Development and psychometric evaluation of a quality nursing care scale from nurses’ perspective. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 1741–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaca, A.; Kaya, L.; Kaya, G.; Harmanci Seren, A.K. Psychometric properties of the Quality Nursing Care Scale–Turkish version: A methodological study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malak, M.Z.; Abu Safieh, A.M. Association between work-related psychological empowerment and quality of nursing care among critical care nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 2015–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulou, A.; Rovithis, M.; Kelesi, M.; Vasilopoulos, G.; Sigala, E.; Papageorgiou, D.; Moudatsou, M.; Koukouli, S. What Quality of Care Means? Exploring Clinical Nurses’ Perceptions on the Concept of Quality Care: A Qualitative Study. Clin. Pract. 2022, 12, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantsupawat, A.; Wichaikhum, O.A.; Abhicharttibutra, K.; Sadarangani, T.; Poghosyan, L. The relationship between nurse burnout, missed nursing care, and care quality following COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 5076–5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehranineshat, B.; Rivaz, M.; Kargar Dolatabadi, E. Psychometric testing of the Persian version of the Nursing Care Quality Scale: A methodological study. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 6491–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.J.; Chung, H.; Jo, Y.M. Relationships between alternative nurse staffing level measurements and nurses’ perceptions of staffing adequacy, fatigue, and care quality. J. Nurs. Manag. 2023, 31, e3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León Román, C.A. Validation of an instrument for measuring perceived quality of nursing care in the hospital context. Rev. Cubana Enferm. 2023, 39, e6140. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.; Kunaviktikul, W.; Abhicharttibutra, K.; Wichaikhum, O.A. Causal modelling of factors influencing quality of nursing care in China. Pac. Rim Int. J. Nurs. Res. 2023, 27, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivaz, M.; Tehranineshat, B. The relationship between professional collaboration and quality of nursing care in intensive care units: A cross-sectional study. J. Crit. Care Nurs. 2023, 16, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Marcomini, I.; Pendoni, R.; Bozzetti, M.; Mallio, M.; Riboni, F.; Di Nardo, V.; Caruso, R. Psychometric characteristics of the Quality of Oncology Nursing Care Scale (QONCS): A validation study. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 40, 151751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollaoğlu, M.; Basit, G.; Su, S.; Boy, Y. Turkish validity and reliability of the Quality Nursing Care Scale (QNCS-T). Bangladesh J. Med. Sci. 2024, 23, 826–833. [Google Scholar]

- Toptaş Kılıç, S.; Öz, F. Validity and reliability of the Palliative Nursing Care Quality Scale in Türkiye. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2024, 15, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitamana, E.W.; Abhicharttibutra, K.; Wichaikhum, O.A.; Nansupawat, A. Factors predicting the quality of care among nurses in tertiary hospitals in Fiji: A cross-sectional study. Pac. Rim Int. J. Nurs. Res. 2024, 28, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, M.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, T.; Wang, Y.; Gai, Y. The Chinese version of the Palliative Nursing Care Quality Scale: Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validity. J. Palliat. Care 2023, 39, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattila, T.; Stolt, M.; Katajisto, J.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Introduction and systematic review of the Good Nursing Care Scale. J. Clin. Nurs. 2025, 34, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCance, T.; McCormack, B. The Person-centred Nursing Framework: A mid-range theory for nursing practice. J. Res. Nurs. 2025, 30, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Author(s)/Year | Country | Instrument(s) | Definition of Quality | Sample and Context | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Redfern & Norman/1995 [11] | UK | Monitor, Senior Monitor, Qualpacs | Aligns with the nursing process and incorporates autonomy, documentation, and PCC. | 11 wards (medical-surgical, elderly care). | Senior Monitor and Qualpacs are suitable for assessing quality in elderly care. Monitor DG3 is useful for high-dependency patients, but other subscales lack validity. Implementation challenges were noted across tools. |

| Redfern & Norman/1996 [12] | UK | Monitor, Senior Monitor, Qualpacs | Four domains: care planning, physical care, non-physical care, and evaluation. Influenced by patient dependency, omitted care activities, and congrunce between nurse/patient perceptions. | 11 wards (medical-surgical, elderly care). 123 patients and 80 nurses. | Senior Monitor demonstrated better validity than Monitor. Monitor should be used as four separate schedules (DG1–DG4), with DG3 showing strongest performance. Approximately 10% of items lacked endorsement and may be unnecessary. |

| Mrayyan/2006 [13] | Jordan | Mueller/McCloskey Satisfaction Scale (MMSS); Eriksen’s Satisfaction with Nursing Care Questionnaire; Quality of Nursing Care Questionnaire—Head Nurse | Care provided according to hospital standards and job requirements. | 200 nurses, 510 patients, and 26 head nurses in one educational hospital | Nurses reported neutral satisfaction levels; patients were moderately satisfied. Head nurses rated care quality as generally high. Positive correlations were observed between nurse job satisfaction and patient satisfaction. |

| Lee & Yom/2007 [14] | South Korea | SERVQUAL (adapted and translated into Korean) | Defined as the gap between expectations and performance across five dimensions: tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy. | 272 patients and 282 nurses from six hospitals in Korea | Nurses had higher expectations and performance ratings, while patients reported higher satisfaction. A significant expectation-performance gap indicated poor perceived quality. Satisfaction strongly correlated with intent to revisit. Results suggest a need for managerial strategies to align staff and patient perspectives. |

| Andersson & Lind/2008 [15] | Sweden | Karen-patient and Karen-personnel instruments (part of the KISAAL system) | Based on Donabedian’s model (Structure-Process-Outcome), quality includes staff characteristics, affective care, patient-staff relationships, and patient outcomes (e.g., satisfaction, health improvement). | Conduced in a Swedish university hospital with 64 patients and 42 staff members from a medical-surgical ward. | The reduced instruments retained conceptual integrity and demonstrated good reliability. They allow comparison between patient and staff perspectives on structure and process quality, though not outcome quality. |

| Zhao et al./2009 [16] | China | Perception of Quality Nursing Care Scale (PQNCS) | Six categories: staff characteristics, care-related activities, preconditions for care, physical environment, progress of nursing process, and cooperation with relatives. | Conducted in 18 non-ICUs at a tertiary hospital in Harbin, China, with 221 nurses and 383 patients. | Both groups rated care quality as high, but significant differences were found in perceptions of staff characteristics, care-related activities, and nursing process. Cultural factors and expectations influenced patient responses |

| Burhans & Alligood/2010 [9] | US | No formal instrument; qualitative study using hermeneutic phenomenology | Quality nursing care is defined as meeting human needs through caring, empathetic, respectful interactions, grounded in responsibility, intentionality, and advocacy. | 12 female registered nurses from acute care hospitals in southeastern USA. | The essence of quality nursing care lies in six themes: responsibility, caring, intentionality, empathy, respect, and advocacy. These reflect the art of nursing and are consistently recognized by nurses in their own and others’ practice. Findings suggest that incorporating these themes into education and management could improve care quality. |

| Maes et al./2010 [17] | France | IGEQSI (Instrument Global d’Évaluation de la Qualité des Soins Infirmiers) | Not explicitly defined; focus on affective commitment and satisfaction as outcomes of quality initiatives. | 30 nurses and nursing assistants in a French clinic. | Job satisfaction is linked to professional experience and value alignment. Affective commitment is fostered by autonomy, recognition, and team cohesion. Implementation of quality tools can enhance engagement and satisfaction. |

| Donmez & Ozbaır/2010 [18] | Turkey | Good Perioperative Nursing Care Scale (GPNCS)—Turkish version | Includes physical care, giving information, support, respect, personnel characteristics, environment, and nursing process. | 346 patients and 159 nurses from 11 hospitals in Turkey. | The Turkish GPNCS is a valid and reliable tool for assessing perioperative nursing care. It supports both patient and nurse perspectives and is suitable for clinical quality improvement. |

| Lindgren et al./2011 [19] | Sweden | Karen-Patient and Karen-Personnel Instruments | Based on Donabedian’s Structure–Process–Outcome (SPO) model and qualitative interviews with patients and staff. | Conducted in medical and surgical wards in a Swedish hospital. 95 patients and 120 staff (nurses and nursing aides) participated. | The Karen instruments demonstrate good construct validity and internal consistency. Suitable for clinical use to assess and compare patient and staff perceptions of nursing care quality. |

| Cline et al./2011 [20] | USA | None (qualitative content analysis of narrative responses) | Quality care is defined through three themes: RN presence, developing relationships, and facilitating the flow of knowledge and information. | 171 narrative responses from early-career hospital-based RNs in the U.S., as part of a longitudinal survey. | High-quality nursing care was described as relational and process-oriented, focusing on presence, trust-building, and evidence-based communication. The study underscores the need for quality indicators that go beyond outcomes to reflect core nursing processes. |

| Wilson et al./2012 [21] | Australia | No single instrument; 57 indicators developed and refined using a modified Delphi process. | Framed using Donabedian’s model: Structure: Staffing levels, skill mix; Process: Pain management, assessments; Outcome: Pressure ulcers, infections, unplanned extubation | Modified Delphi study with 52 pediatric nursing experts (clinicians, educators, managers) across Australia, using three rounds of surveys. | 42 indicators validated for pediatric care; traditional adult indicators (e.g., mortality, DVT) deemed unsuitable. Data collection from case notes was often difficult. Ongoing research is recommended to evaluate indicator utility and frequency in real-world settings. |

| Bogaert et al./2013 [22] | Multicentric | Revised Nursing Work Index (NWI-R) Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) Intensity of Labour Scale Decision Latitude and Social Capital Scales | Nurses’ self-assessed quality at the unit, shift, and hospital levels, influenced by collaboration, management support, and workload. | Cross-sectional survey of 1201 nurses across 9 hospitals in Belgium (general, university, and hospital group settings). | Strongest predictor of job satisfaction and quality perception was unit-level nurse management. Workload and burnout mediated negative effects, while decision latitude and social capital buffered against burnout. Empowered, collaborative environments enhance care quality. |

| Andersson & Lindgren/2013 [23] | Sweden | Karen-patient and Karen-personnel instruments | Grounded in Donabedian’s model and patient-centered care. Quality assessed across subscales: satisfaction, influence, staff competence, caring/uncaring, integrity, and organization. | Swedish regional hospital; 95 patients and 120 nursing staff (registered and assistant nurses). | Both groups rated care quality positively overall. Patients scored staff competence highly but expressed lower satisfaction with organizational factors like continuity of care. The Karen tools effectively highlight perceptual gaps and areas for improvement. |

| Charalambous & Adamakidou/2014 [24] | Cyprus and Greece | Quality of Oncology Nursing Care Scale (QONCS) | Holistic concept including five dimensions: support and confirmation, spiritual caring, sense of belonging, being valued, and being respected. | Multicenter study in Cyprus and Greece with 418 hospitalized cancer patients. Used a mixed-methods approach: literature review, expert input, pilot study, and large-scale validation. | QONCS is a valid and reliable instrument that captures a holistic, patient-centered view of oncology nursing care. It uniquely integrates spiritual and emotional aspects, addressing key gaps in existing tools. |

| Rossaneis et al./2014 [25] | Brasil | Electronic questionnaire developed by the authors | Not explicitly defined; focused on the presence and use of quality indicators in practice. | Nine teaching hospitals in Paraná, Brazil; participants were nurse managers. | While nursing quality indicators are commonly used, they lack standardization and are not benchmarked across institutions. The study highlights the need for unified strategies to evaluate, compare, and improve nursing care quality in varied contexts. |

| Voyce et al./2015 [26] | Portugal | Adapted questionnaire based on Donabedian’s model. | Structured around Donabedian’s three components: Structure: Resources, facilities, organization; Process: Nurse-patient interactions; Outcome: Results like satisfaction and health status. | Emergency department (obstetrics/gynecology) in Algarve Hospital Centre, Portimão, Portugal. Sample: 23 nurses. | Donabedian’s model was supported as a valid structure for assessing nursing care quality, despite moderate internal consistency. Process and outcome domains showed perceptual overlap. The study highlights the need for robust statistical techniques—especially for small samples—to explore multidimensional quality constructs. |

| Koy et al./2016 [27] | Thailand | Good Nursing Care Scale (GNCS), Karen-patient and Karen-personnel, Patient Perception of Hospital Experience with Nursing (PPHEN), Nurses’ Assessment of Quality Scale (NAQS-ACV) | Varies by perspective—nurses emphasize competence and empathy; patients prioritize responsiveness and communication. The review highlights NCQ as a multidimensional concept. | Systematic review of 18 studies conducted across the USA, Europe, Asia, and Canada. | No single universal instrument exists. Perceptions of quality differ between patients and nurses, emphasizing the importance of selecting tools that suit the specific context and purpose. Greater consensus and standardization in NCQ measurement are needed. |

| Martins et al./2016 [28] | Portugal | Escala de Perceção das Atividades de Enfermagem que Contribuem para a Qualidade dos Cuidados (EPAECQC) | Aligned with standards from the Portuguese Order of Nurses, covering seven domains: client satisfaction, health promotion, complication prevention, well-being and self-care, functional readaptation, organization of care, and professional responsibility. | Hospital in northern Portugal; 775 nurses participated (May–July 2014). | The EPAECQC is a robust, valid, and reliable instrument. It reflects national care quality standards and is applicable for both research and practical improvements in nursing care. |

| Laschinger et al./2016 [29] | Canada | Conditions for Work Effectiveness Questionnaire (CWEQ) Nursing Work Index-Revised (NWI-R) Professional Practice Behaviours Scale (developed for the study) Single-item measure for perceived care quality | Based on nurses’ perceptions of their ability to deliver care aligned with professional standards. Influencing factors include empowerment, autonomy, practice control, and collaboration. | National survey of 393 new graduate nurses in Canada (within their first 3 years of practice). | Work environments that empower and support professional practice improve nurses’ behaviors, perceived care quality, job satisfaction, and retention. Organizational strategies fostering empowerment and collaboration are crucial for sustaining quality nursing care. |

| Alcântara-Garzin & Melleiro/2017 [30] | Brazil | Custom-built Likert-scale tool; Based on Donabedian’s model: Structure: Resources, infrastructure; Process: Nursing activities, interpersonal relationships; Outcome: Service characteristics, patient satisfaction, safety | Quality is seen as the interaction of structure, process, and outcomes, with an emphasis on the ratio between service effectiveness and user expectations. The goal is to ensure a safe environment that minimizes risks to users. | Private diagnostic medicine institution, São Paulo, Brazil Participants: 203 nursing professionals | The validated instrument is reliable and useful for guiding managerial and clinical actions to improve nursing care quality in diagnostic medicine. |

| Koy et al./2017 [31] | Cambodia | Cambodian Nursing Care Quality Scale (CNCQS); Measures the degree to which nursing activities meet professional standards and patient needs, as perceived by nurses. | The degree to which nursing activities meet professional standards and patient needs, as perceived by nurses. | 225 registered nurses from 12 hospitals across Cambodia. | CNCQS is a valid and reliable tool for assessing nursing care quality in Cambodia; Further testing is recommended across diverse settings; The tool supports quality improvement and professional development in nursing. |

| Martins et al./2017 [32] | Portugal | Escala da Perceção das Atividades de Enfermagem que Contribuem para a Qualidade dos Cuidados | Nursing care quality based on Ordem dos Enfermeiros’ standards emphasizing patient satisfaction, health promotion, prevention, well-being, functional readaptation, organization, responsibility, and rigor. | 36 public hospitals across mainland Portugal; 3451 nurses. | Nurses commonly implement responsibility and prevention activities but less frequently health promotion, self-care, and functional readaptation, indicating a need for practice redesign and additional training. |

| Alsyouf et al./2018 [33] | Jordan | Karen-personnel instrument | Quality in psychiatric nursing care includes psychosocial relationships, commitment, job satisfaction, openness/proximity, competence development, and safety/insecurity; quality indicators differ from other health services and require continuous observation and measurement. | Psychiatric inpatient units in Jordan. | 64% of nurses rated psychiatric nursing care as satisfactory; Nurses generally perceive the quality of care more positively than patients. Highlights differing perceptions between nurses and patients and the unique challenges in measuring psychiatric nursing care quality. |

| Gaalan et al./2019 [34] | Mongolia | Good Nursing Care Scale (GNCS) | Quality defined as excellence in addressing patients’ physical, psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual needs (Leino-Kilpi model). | 346 registered nurses from seven tertiary public hospitals in Ulaanbaatar and four other regions. | Nurses with higher competence and positive practice environments deliver better nursing care quality. |

| Stolt et al./2019 [35] | Finland | Good Nursing Care Scale (GNCS) | Quality is based on Donabedian’s model (structure, process, outcome) and action theory, including safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, and nurse competence. | One university hospital with 480 surgical patients and 167 nurses. | GNCS is a valid and reliable instrument for assessing nursing care quality from both patient and nurse perspectives, though some items may need revision for improved fit. |

| Egea et al./2020 [36] | Spain | Palliative Nursing Care Quality Scale (PNCQS) | Quality is defined as holistic, patient- and family-centered palliative care, including symptom control, therapeutic relationships, spiritual support, and continuity of care. It emphasizes personal values such as growth, dedication, and the meaningfulness of nursing. | Stage 1 involved qualitative interviews with 10 key informants in Spain; Stage 2 included 100 nurses from Madrid; Stage 3 surveyed 176 nurses from various palliative care centers across the country. | The PNCQS is a valid and reliable instrument for evaluating the quality of palliative nursing care. It supports professional autonomy and provides a foundation for continuous improvement in care practices. |

| Tsogbadrakh et al./2021 [37] | Mongolia | Quality Nursing Care Scale—Mongolia (QNCS-M) | Quality nursing care is defined as the provision of physical, psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual care, shaped by cultural norms, patient needs, and the healthcare environment. | Phase I involved qualitative development; Phase II included validation with 440 nurses from 9 public hospitals in Ulaanbaatar. | The QNCS-M is a culturally relevant, valid, and reliable instrument for evaluating nursing care quality in Mongolia and can be adapted for use in comparable healthcare contexts. |

| Moen et al./2021 [38] | Norway | QPC-COPS (Quality in Psychiatric Care—Community Outpatient Psychiatric Staff), FINC-NA (Families’ Importance in Nursing Care—Nurses’ Attitudes), SOC-13 (Sense of Coherence Scale, 13-item version). | Quality of care is assessed across eight dimensions: Encounter, Participation (Empowerment and Information), Discharge, Support, Environment, Next of Kin, Accessibility. It is influenced by attitudes toward family involvement and the professional’s sense of coherence (SOC). | Cross-sectional quantitative study with 56 community mental health professionals (primarily nurses) from 17 municipalities in Norway, all with at least one year of experience. | Overall quality of care was rated high, especially in the “Encounter” dimension. Family involvement was not seen as a burden, but their participation as conversational partners was limited. Professionals with higher SOC scores reported higher perceived care quality and fewer negative views of family involvement. Interestingly, longer work experience correlated with lower ratings of care quality, and nurses had more positive attitudes toward family involvement compared to other professionals. |

| Liu et al./2021 [39] | China | Quality Nursing Care Scale (QNCS) | Quality nursing care was conceptualized through six key dimensions: team characteristics, task-oriented activities, human-oriented activities, physical environment, patient outcomes, and care preconditions, reflecting both technical and relational aspects of care. | 302 nurses participated through random sampling. | The QNCS is a valid and reliable instrument for evaluating nursing care quality from the perspective of nurses in the Chinese healthcare context. |

| Karaca et al./2022 [40] | Turkey | Quality Nursing Care Scale (QNCS)—Turkish version | Quality is defined from the perspective of nurses and includes dimensions such as the physical environment, staff characteristics, nursing tasks, and patient outcomes. | 225 nurses from a training and research hospital in Turkey. | The Turkish adaptation of the QNCS is a valid and reliable tool for assessing nursing care quality from nurses’ perspectives and can effectively support clinical practice improvement in Turkish healthcare settings. |

| Malakeh et al./2022 [41] | Jordan | Karen-personnel instrument | The instrument assesses quality of nursing care through six subscales: psychosocial relationships, commitment, job satisfaction, openness/proximity, competence development, and safety/insecurity, reflecting nurses’ perceptions of the relational and organizational aspects of care. | Intensive Care Units (ICUs) | Psychological empowerment at work is significantly associated with improved nursing care quality. Enhancing empowerment among ICU nurses is necessary to support higher standards of care. |

| Stavropoulou et al./2022 [42] | Greece | No formal instrument; qualitative descriptive study using semi-structured interviews | Quality nursing care is defined as holistic care that meets patient needs, achieves optimal outcomes, and is grounded in communication, teamwork, leadership, and personal commitment. | 10 female clinical nurses from a public hospital in Athens. | Four core themes were identified: quality care is holistic, good care depends on interpersonal relationships, leadership plays a central role, and personal responsibility drives care quality. Nurses highlighted empathy, teamwork, and leadership support as critical components, suggesting a need for stronger organizational and educational strategies to promote holistic, high-quality nursing care. |

| Nantsupawat/2023 [43] | Thailand | Maslach Burnout Inventory—Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS), MISSCARE Survey, and two single-item Likert-scale measures for perceived quality of care | Quality of care was self-reported by nurses using Likert-scale questions at both unit and shift levels; burnout was defined as emotional exhaustion (EE score ≥ 27), and missed care as any care activity reported as missed with any frequency. | Cross-sectional survey of 394 nurses from 12 general hospitals in Thailand, conducted between August and October 2022; all participants had at least one year of nursing experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. | Burnout was strongly associated with increased missed care and lower perceived quality of care. Specifically, burnout raised the odds of missed care by 1.61 times, poor care during the last shift by 3.37 times, and poor overall unit care by 2.62 times. Emotional exhaustion remains a major concern post-pandemic, underscoring the need for organizational support strategies such as improved staffing and access to mental health resources. |

| Tehranineshat et al./2023 [44] | Iran | Nursing Care Quality Scale—Persian (CNCQS-Persian) | Rooted in Donabedian’s model (Structure–Process–Outcome), quality is defined through six domains: patient outcomes, ethics-oriented activities, nurses’ characteristics, task requirements, nursing process, and physical environment. | 310 nurses from four teaching hospitals in Iran; data collected between May 2021 and March 2022. | The CNCQS-Persian is a psychometrically sound instrument for assessing nursing care quality in Iran. Its culturally adapted structure allows for a comprehensive evaluation of quality in line with local clinical practices and healthcare expectations. |

| Hong et al./2023 [45] | South Korea | Korean Patient Classification System—General Ward (KPCS-GW), Work Sampling Tool, and an Ad Hoc survey for perceived staffing adequacy, fatigue, and care quality | Quality of care was self-rated by nurses using a 4-point Likert scale, considered in relation to perceived staffing adequacy and fatigue. Staffing adequacy was assessed on a scale from −10 to +10, fatigue on a 0–10 scale. Nurse staffing was measured Via three approaches: nurse-to-patient ratio, acuity-adjusted work intensity, and demanded nursing hours per nurse. | Cross-sectional study conducted in a general hospital across 6 wards, including 90 nurses and 5536 patients; data collected daily over a 4-week period in 2022. | The study found that nurse-to-patient ratios are insufficient for assessing staffing adequacy. Acuity-adjusted metrics such as work intensity and nursing hours per patient day are better predictors of nurse fatigue and perceived care quality. Integrating these measures into staffing models can enhance care quality and reduce nurse burnout. |

| Román/2023 [46] | Cuba | Instrument to measure the perceived quality of nursing services in the hospital context | Quality is a complex concept beyond technical and mechanical aspects, involving human care, empathy, and integration of values and scientific knowledge. It is based on Donabedian’s model with three dimensions: Technical (adherence to standards, technical ability), Interpersonal (nurse-patient relationship, communication, ethics), and Comfort (physical and emotional environment). | Hospital setting involving 9 experts, 15 judges, 30 hospitalized patients, and 10 nursing professionals. | The instrument demonstrated high content validity and reliability, allowing a holistic evaluation of perceived nursing care quality from both patient and professional viewpoints. It is useful to identify gaps in care and to improve nursing quality in hospitals. |

| Xue et al./2023 [47] | China | Good Nursing Care Scale (GNCS), Practice Environment Scale (PES-NWI), Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (3-UWES), Psychological Empowerment Scale (PES), High-Performance Work Systems Scale (HPWSS), Perceived Organizational Support (8-SPOS) | Quality of nursing care is defined as the degree of excellence that meets patients’ spiritual, mental, social, physical, and environmental needs. | 784 nurses from three university-affiliated hospitals in China. | Practice environment, psychological empowerment, and work engagement were found to have significant positive effects on nursing care quality. The proposed causal model is promising but requires further testing and refinement to confirm its applicability. |

| Rivaz & Tehranineshat/2023 [48] | Iran | Professional Collaboration Subscale (from the Professional Practice Environment Nursing Instrument), Nursing Care Quality Scale (NCQS) | Quality of nursing care is defined as the ethical, safe, and effective delivery of care, with professional collaboration—particularly ethics-oriented activities—being a key predictor. | Cross-sectional study with 330 ICU nurses in Shiraz, Iran. | Professional collaboration was significantly associated with higher quality nursing care, with ethics-oriented collaboration having the strongest impact. The study suggests that educational programs focusing on professional ethics could enhance care quality in ICU settings. |

| Marcomini et al./2024 [49] | Italy | Quality of Oncology Nursing Care Scale (QONCS)—Italian version | Quality is defined as patients’ subjective perception of nursing care, including professional support, spiritual respect, sense of belonging, feeling valued, and being respected. | Cross-sectional study involving 219 oncology patients from three hospitals in Northern and Central Italy. | The Italian QONCS is a valid and reliable tool for comprehensively assessing nursing care quality in oncology settings. Patient factors such as age, marital status, and employment status were found to influence perceived quality of care. |

| Mollaoğlu et al./2024 [50] | Turkey | Quality Nursing Care Scale—Turkish version (QNCS-T) | Quality is understood as holistic care, encompassing psychological, spiritual, social, and professional dimensions. | 347 nurses from a university hospital in Turkey participated in the study. | The QNCS-T is a valid and reliable instrument for assessing nursing care quality in Turkey, supporting a holistic evaluation approach and serving as a useful tool for guiding nurse training and quality improvement initiatives. |

| Toptaş et al./2024 [51] | Turkey | Palliative Nursing Care Quality Scale—Turkish version (PNCQS-TR) | Holistic palliative nursing care encompassing symptom management, communication, ethical responsibility, family involvement, and continuity of care. | Methodological study with 210 palliative care nurses from various units including oncology, ICU, and geriatrics in Turkey; data collected online from September to December 2021. | The PNCQS-TR is a valid and reliable instrument for assessing palliative nursing care quality in Turkey. It facilitates self-assessment among nurses and can be used to support quality improvement efforts in clinical practice. |

| Veitamana et al./2024 [52] | Fiji Islands | Quality of Care Scale (QOCS) developed by Aiken and Patrician | Nursing care quality as a critical factor influencing healthcare service success, measured by nurses’ perceptions of care quality on a 4-point scale from poor to excellent, affected by nurse shortages, workload, and work conditions. | Cross-sectional descriptive-predictive study involving 744 registered nurses in three tertiary hospitals in Fiji. | 72.58% of nurses rated overall care quality as good or excellent. Relational coordination and job satisfaction were significant predictors positively influencing nurses’ perceptions of care quality, highlighting the importance of interpersonal and organizational factors in perceived nursing care quality. |

| Liu et al./2024 [53] | China | Palliative Nursing Care Quality Scale (PNCQS)—Chinese version | Quality is defined as overall palliative nursing care quality encompassing symptom management, communication, ethical responsibility, family involvement, and continuity of care. | Mainland China, palliative nursing care context. | The Chinese version of PNCQS is valid and reliable for assessing palliative nursing care quality in mainland China. |

| Mattila et al./2025 [54] | Finland | Good Nursing Care Scale (GNCS) | Patient-centered care encompassing nurse characteristics, care activities, environment, care process, empowerment, and family collaboration. | Systematic review across multiple countries and care settings (surgical, pediatric, ICU, etc.). | The GNCS is a valid and reliable tool for assessing patient-centered nursing care internationally and is suitable for long-term quality monitoring in diverse healthcare settings. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Correia, P.; Bernardes, R.A.; Caldeira, S. Instruments for Assessing Nursing Care Quality: A Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090342

Correia P, Bernardes RA, Caldeira S. Instruments for Assessing Nursing Care Quality: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(9):342. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090342

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorreia, Patrícia, Rafael A. Bernardes, and Sílvia Caldeira. 2025. "Instruments for Assessing Nursing Care Quality: A Scoping Review" Nursing Reports 15, no. 9: 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090342

APA StyleCorreia, P., Bernardes, R. A., & Caldeira, S. (2025). Instruments for Assessing Nursing Care Quality: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports, 15(9), 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090342