Process Model for Transitioning Care Responsibility to Adolescents and Young Adults with Biliary Atresia: A Secondary and Integrative Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. The Aim of the Present Study

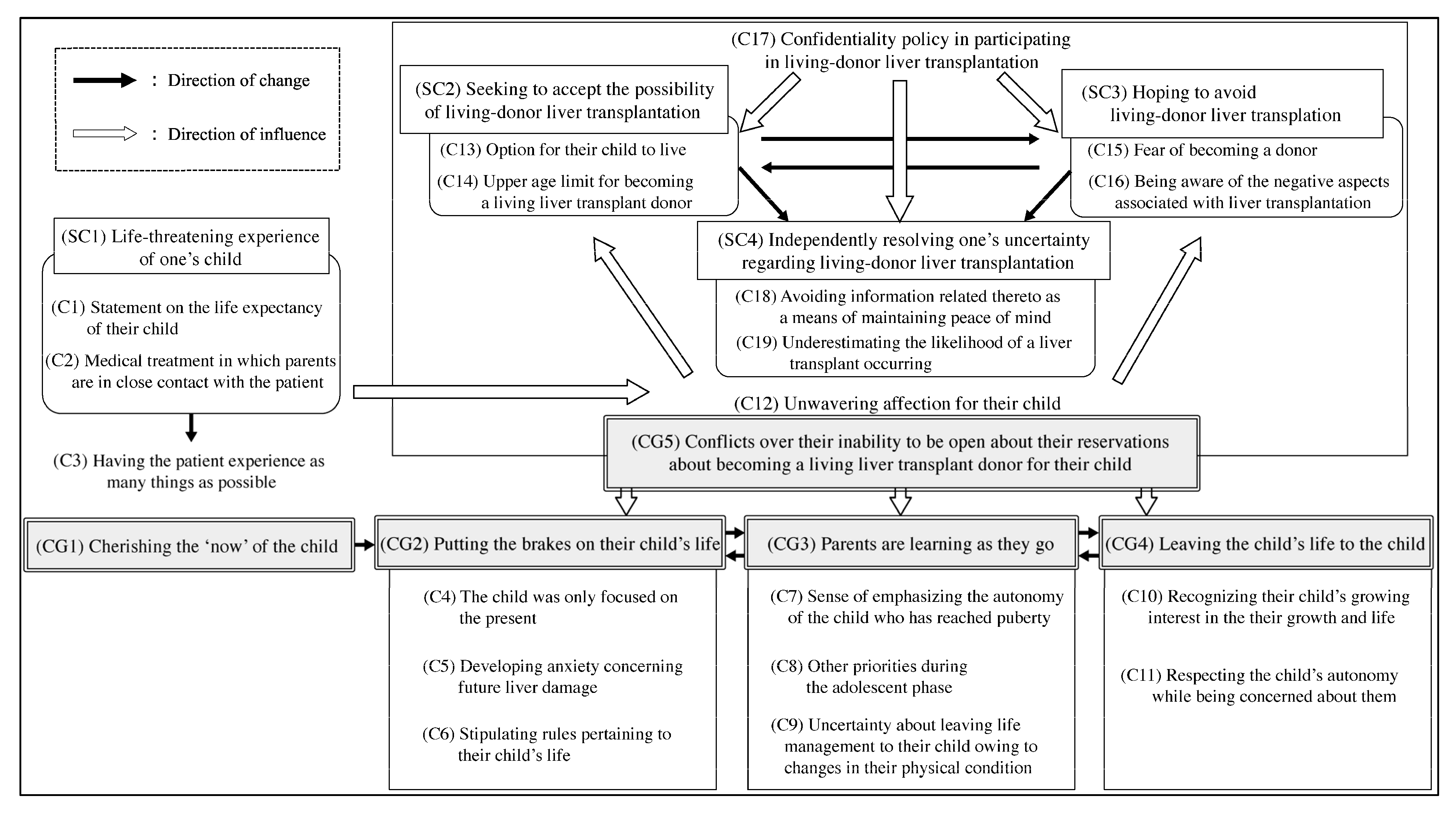

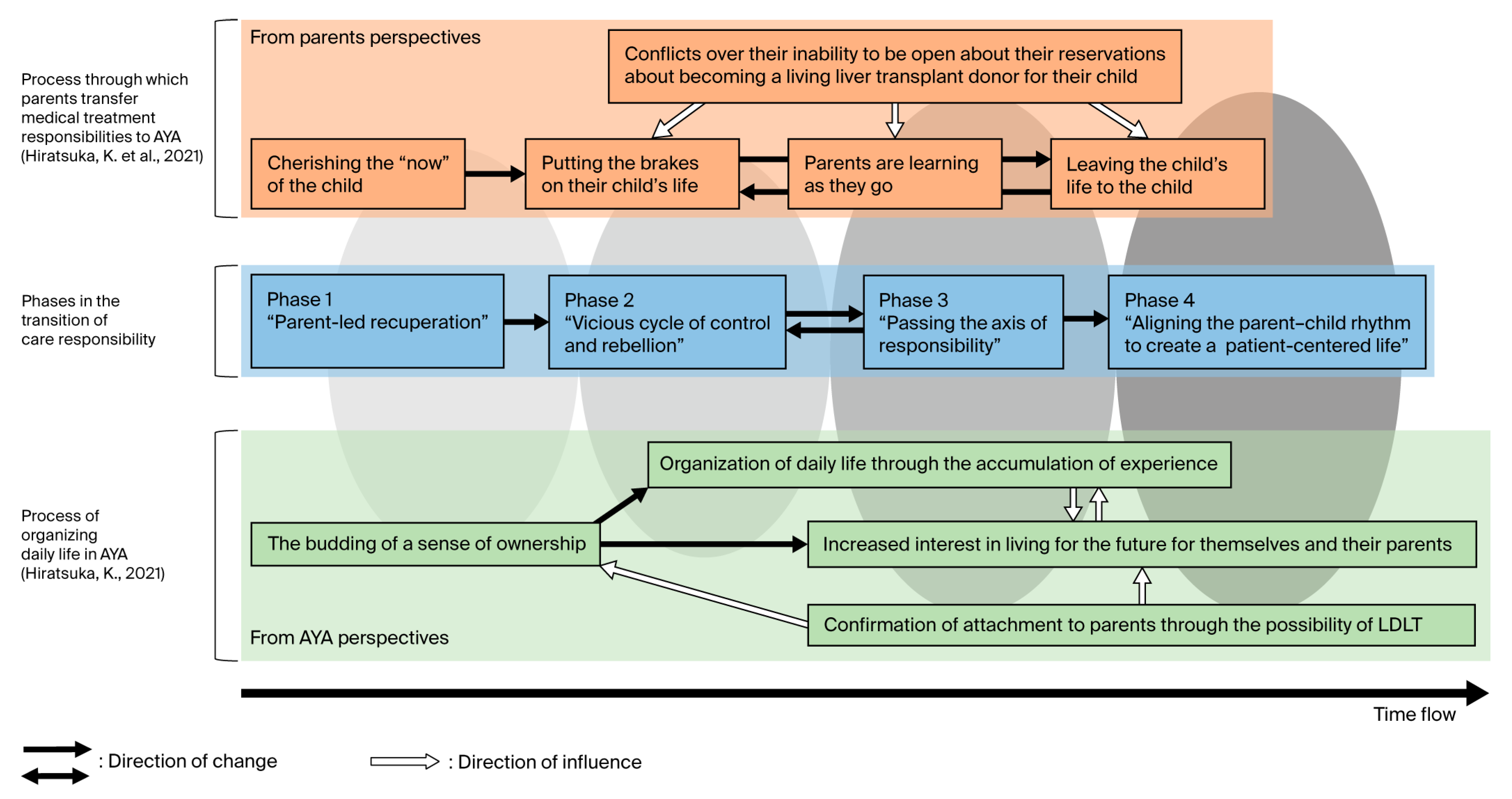

1.3. Summary of Prior Process Models

1.3.1. Process of Daily Life Organization in Adolescents and Young Adults with Biliary Atresia Who Survive with Their Native Livers (Based on Hiratsuka [8])

1.3.2. Process Through Which Parents Transfer Medical Treatment Responsibilities to Their Adolescent and Young Adult Children with Biliary Atresia Who Survive with Their Native Livers (Based on Hiratsuka et al. [10])

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Population

2.3. Instruments

- “How do you and your parents share daily and health-related responsibilities?”

- “How has your role changed over time?”

- “What do you talk about with your parents regarding your illness or future, including liver transplantation?”

- “How have you supported your child’s care and routines?”

- “When and how did you explain the diagnosis to your child?”

- “How do you discuss the future or transplantation?”

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Analysis in the Two Prior Studies

2.5.2. Secondary Analysis Using Modified Grounded Theory Approach

2.5.3. The Integrative Process and Development of the Process Model

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Phases in the Transition of Care Responsibility

3.1.1. Parent-Led Recuperation

(Interviewer: Did you ever question or ask ‘Why?’ when they restricted your recuperation behavior or daily activities?)Patient C (19 y/o, female):I never did. I did as I was told.(Interviewer: When did you start letting her manage her own medication and make decisions about exercising?)Mother C (50 s):Yes. When she was little, I did everything. I think it was when her medication started to decrease that I started to leave it to her. That was when she was in junior high school. Until then, I was in charge.

Patient E (21 y/o, female):I thought the clothes were cute, but I didn’t like it when they told me to wear tights.Mother E (40 s):Even if I explain to her about the disease, she doesn’t understand, so she is, for lack of a better word, under our control. Parents can freely control their children, and if they say no, it’s no good.

3.1.2. Vicious Cycle of Control and Rebellion

Patient E (21 y/o, female):I was really rebellious against my parents! … When we went shopping for clothes, my sister could choose what she liked, but I had to choose for warmth. I was like, ‘Why?’ I felt like my mother was really obsessed with my physical condition.

Mother E (40 s):As my daughter entered middle school, she began to ask herself, ‘Why can’t I do what everyone else can?’ She began to be reckless. For example, she started staying up late at night. So, we made a curfew in our house. But she didn’t like the rule itself… She didn’t agree.

Patient B (18 y/o, female):I kind of pushed myself too hard while playing. My parents told me that I was catching colds because my body was tired. They said my immune system was weak or something. I thought that was too much… I knew my body was tired, so I tried to adjust by going to bed early and so on. I was taking care of myself in my own way, so I didn’t want my parents to nag me about it.Father B (60 s):I also told my daughter not to do anything too exhausting, I think she wanted to rebel against us as parents. She pushed herself to continue activities in the brass band without listening to me.

Mother A (50 s):When my daughter was in eighth grade, the transplant surgeons became involved, and if she was even a little bit sick, I was like, ‘Oh, what if she gets cholangitis again?’… (To her daughter), ‘Oh, can’t you care a little more?’

3.1.3. Passing the Axis of Responsibility

Mother E (40 s):She’s always wanted to leave the house… so I rented a spare room at her grandma’s house for her to practice and get some experience of living on her own.

Mother C (50 s):She always said she wanted to live on her own, so I left it up to her. I did at least warn her not to go to bed too late, but I tried not to pay too much attention.Patient C (19 y/o, female):Living alone is tough in its own way, but I think I am able to take care of my eating habits. Since my parents don’t live with me, I feel a sense of responsibility that I have to manage everything myself.

Patient H (25 y/o, male):The gas station where I worked before was a pretty physically demanding job. When I was working there, there were periods when the results of my blood tests were poor, and I wondered what I could do. It was beyond my ability to adjust and manage my own life. I had not told the company about my illness. I wanted to work, keeping my illness hidden.Mother H (50 s):When I advise my son about his daily life, he often says, ‘I know!’ And I say, ‘If you knew what you were doing, you wouldn’t have done this!’ After my son entered the workforce, he and I continued to have this exchange. He never told his boss about his illness. Without my knowledge, he worked just like a normal,… healthy young man. When the doctor saw the results of his blood test, he said, ‘It’s pretty bad.’ At the time, he was renting an apartment, and we only had occasional contact with him. I panicked and forced my son to move back home immediately.

3.1.4. Aligning the Parent–Child Rhythm to Create a Patient-Centered Life

Patient G (24 y/o, female):My doctor said, ‘In actuality, we don’t know the cause (of the sudden onset of cholangitis).’ So, my mother and I both said to each other, ‘If my doctor doesn’t know, there’s nothing we can do about it.’ My mother and I are this way.

Mother E (40 s):My daughter told me that the doctor talked to her about a transplant. She said she didn’t want a living-donor liver transplant… She said, ‘I want to live with my native liver if possible.’ We then talked about what we would do to make that happen.

3.2. Supplementary Analysis Integrating Prior Studies for Process Model Development

- In the “parent-led recuperation” phase, AYAs demonstrated [a budding sense of ownership], while parents exhibited [a cherishing of the “now” of the child] and [putting the brakes on their child’s life]. Emerging discomfort in AYAs signaled early tension within the dyad.

- In the “vicious cycle of control and rebellion” phase, conflict escalated, with the persistence of [a budding sense of ownership] among AYAs and [parents learning as they go]. Parental overinvolvement often intensified during episodes of worsening health or physician referrals.

- The “passing the axis of responsibility” phase was associated with AYAs’ [organization of daily life through the accumulation of experience] and parents’ [decision to leave the child’s life to the child]. However, misalignment in readiness sometimes caused health deterioration and regression to earlier phases.

- The “aligning the parent–child rhythm to create a patient-centered life” phase reflected increasing alignment in perceptions of living-donor liver transplantation. AYAs engaged with [confirmation of attachment to parents through the possibility of living-donor liver transplantation], while parental [conflicts over their inability to be open about their reservations] diminished. These shifts facilitated a collaborative life structure.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Influence of Individual and Contextual Factors on the Transition Process

4.2. Evaluation of the Usefulness of the Developed Process Model

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AYAs | Adolescents and young adults |

| LDLT | Living-donor liver transplantation |

| M-GTA | Modified grounded theory approach |

References

- Quinn, S.; Chung, R.; Kuo, A.; Maslow, G.; Ho, J.; Schwartz, L.; Tuchman, L. Transition to adulthood for youth with chronic conditions and special health care needs. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Scheven, E.; Nahal, B.K.; Cohen, I.C.; Kelekian, R.; Franck, L.S. Research questions that matter to us: Priorities of young people with chronic illnesses and their caregivers. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 89, 1659–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFusco, L.A.; Schell, K.A.; Saylor, J.L. Risk-taking behaviors in adolescents with chronic cardiac conditions: A scoping review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 48, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voultsos, P. The competence of adolescents to make autonomous and valid decisions on their own medical treatment. Aristotle Biomed. J. 2021, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Transition from Children’s to Adults’ Services for Young People Using Health or Social Care Services; NICE Guideline NG43; NICE: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng43 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Got Transition. Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition™ 3.0; National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.gottransition.org/six-core-elements/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Tam, P.K.; Wells, R.G.; Tang, C.S.; Lui, V.C.; Hukkinen, M.; Luque, C.D.; De Coppi, P.; Mack, C.L.; Pakarinen, M.; Davenport, M. Biliary atresia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiratsuka, K. Examining how adolescent and young adult patients with biliary atresia survive with their native liver to organize their daily lives. Jpn. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 44, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Japanese Liver Transplantation Society. Liver transplantation in Japan: Registry by the Japanese Liver Transplantation Society. Jpn. J. Transplant. 2023, 58, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiratsuka, K.; Nakamura, N.; Sato, N.; Saito, T. How parents of adolescents and young adults with biliary atresia surviving with native livers transfer the responsibility of medical treatment to their children in Japan. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 61, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos Tavares, A.P.; Seixas, L.; Jayme, C.L.W.; Porta, G.; Seixas, R.; de Carvalho, E. Pediatric liver transplantation: Caregivers’ quality of life. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2022, 25, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turale, S. A brief introduction to qualitative description: A research design worth using. Pac. Rim Int. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 24, 289–291. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, S.J.; Fredkove, W.M. Using a constructivist-oriented modified grounded theory approach in the study of intrafamily trauma communication process in war-affected families: A methodologic example. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2024, 47, E138–E157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, H. Thoughts in and Methods Used in M-GTA. In Mechanisms of Cross-Boundary Learning: Communities of Practice and Job Crafting; Ishiyama, N., Koyama, K., Takeshita, H., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2019; pp. 59–89. [Google Scholar]

- Mocănașu, D.R. Determining the Sample Size in Qualitative Research. In Proceedings of the International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on the Dialogue Between Sciences & Arts, Religion & Education, Târgoviște, Romania, 20–22 November 2020; pp. 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Mohajan, D.; Mohajan, H. Development of grounded theory in social sciences: A qualitative approach. Stud. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2022, 5, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiano, N.; Perry, T.E. Conducting secondary analysis of qualitative data: Should we, can we, and how? Qual. Soc. Work 2019, 18, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalders, J.; Hartman, E.; Pouwer, F.; Winterdijk, P.; van Mil, E.; Roeleveld-Versteegh, A.; Mommertz-Mestrum, E.; Aanstoot, H.J.; Nefs, G. The division and transfer of care responsibilities in paediatric type 1 diabetes: A qualitative study on parental perspectives. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 1968–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, R.; McHugh, G.A.; Swallow, V.; Kirk, S. Shifting responsibilities: A qualitative study of how young people assume responsibility from their parents for self-management of their chronic kidney disease. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domene, J.F.; Socholotiuk, K.; Young, R.A. The early stages of the transition to adulthood: Similarities and differences between mother-daughter and mother-son dyads. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2011, 8, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samyn, M. Transitional care of biliary atresia. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 29, 150948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamuddin, I.; Gordon, E.J.; Levitsky, J. Ethical issues when considering liver donor versus deceased donor liver transplantation. Clin. Liver Dis. 2021, 17, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badour, B.; Bull, A.; Gupta, A.A.; Mirza, R.M.; Klinger, C.A. Parental involvement in the transition from paediatric to adult care for youth with chronic illness: A scoping review of the North American literature. Int. J. Pediatr. 2023, 2023, 9392040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant | Patients’ Age (Years)/Sex | Patients’ Social Status | Patients’ Transplant Status | Parents’ Age (Years)/Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/a | 17/female | High school/living with parents | Surviving with native liver | 50 s/mother |

| B/b | 18/female | University/living with parents | Surviving with native liver | 60 s/father |

| C/c | 19/female | University/living alone | Surviving with native liver | 50 s/mother |

| D/d | 19/female | Vocational college /living with parents | Surviving with living-donor liver transplant (age 14 at transplant) | 40 s/mother |

| E/e | 21/female | Working/living alone | Surviving with native liver | 40 s/mother |

| F/f | 24/female | University (online program)/living with parents | Surviving with native liver, awaiting LDLT | 40 s/mother |

| G/g | 24/female | Working/living with parents | Surviving with native liver | 40 s/mother |

| H/h | 25/male | Working/living with parents | Surviving with native liver | 50 s/mother |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hiratsuka, K.; Nakamura, N. Process Model for Transitioning Care Responsibility to Adolescents and Young Adults with Biliary Atresia: A Secondary and Integrative Analysis. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080308

Hiratsuka K, Nakamura N. Process Model for Transitioning Care Responsibility to Adolescents and Young Adults with Biliary Atresia: A Secondary and Integrative Analysis. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(8):308. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080308

Chicago/Turabian StyleHiratsuka, Katsuhiro, and Nobue Nakamura. 2025. "Process Model for Transitioning Care Responsibility to Adolescents and Young Adults with Biliary Atresia: A Secondary and Integrative Analysis" Nursing Reports 15, no. 8: 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080308

APA StyleHiratsuka, K., & Nakamura, N. (2025). Process Model for Transitioning Care Responsibility to Adolescents and Young Adults with Biliary Atresia: A Secondary and Integrative Analysis. Nursing Reports, 15(8), 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080308