Humanized and Community-Based Nursing for Geriatric Care: Impact, Clinical Contributions, and Implementation Barriers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Study Selection, Inclusion, and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Quality Appraisal

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Quality Appraisal Assessment

3.2. Evolution of Humanized and Community-Based Nursing in Geriatric Care

3.2.1. Historical Background and Theoretical Foundations

3.2.2. Development of Humanistic Models in Nursing

3.2.3. Rise in Community-Based Models

3.2.4. Integration with Public Health and Social Care Frameworks

3.2.5. Emergence of Community-Based Care Models

3.2.6. Alignment with WHO Frameworks and Global Health Strategies

3.3. Clinical Contributions and Impacts of Geriatric Nursing

3.3.1. Improved Outcomes

3.3.2. Models of Care

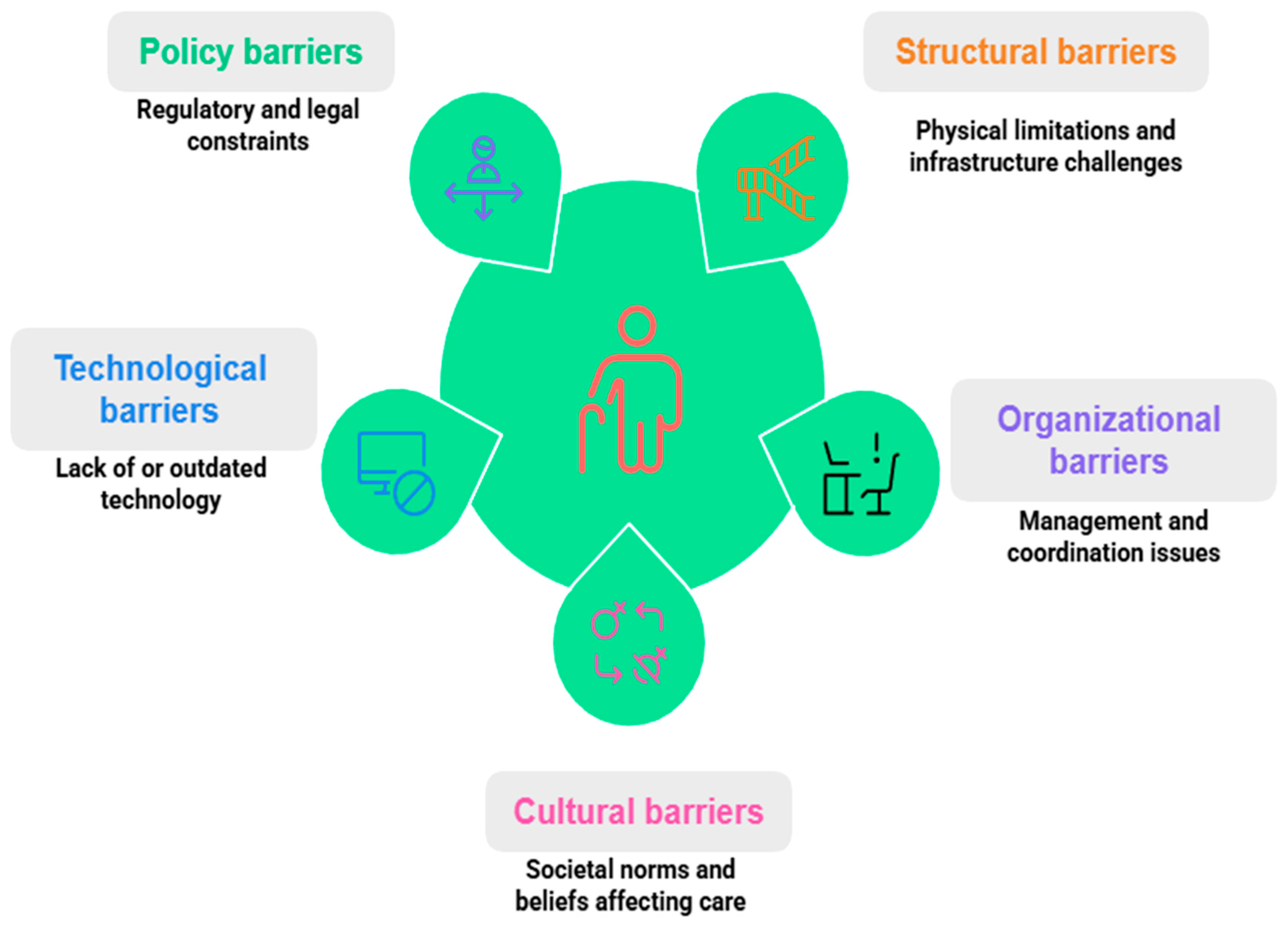

3.4. Barriers to Implementation of Humanized and Community-Based Nursing in Geriatric Care

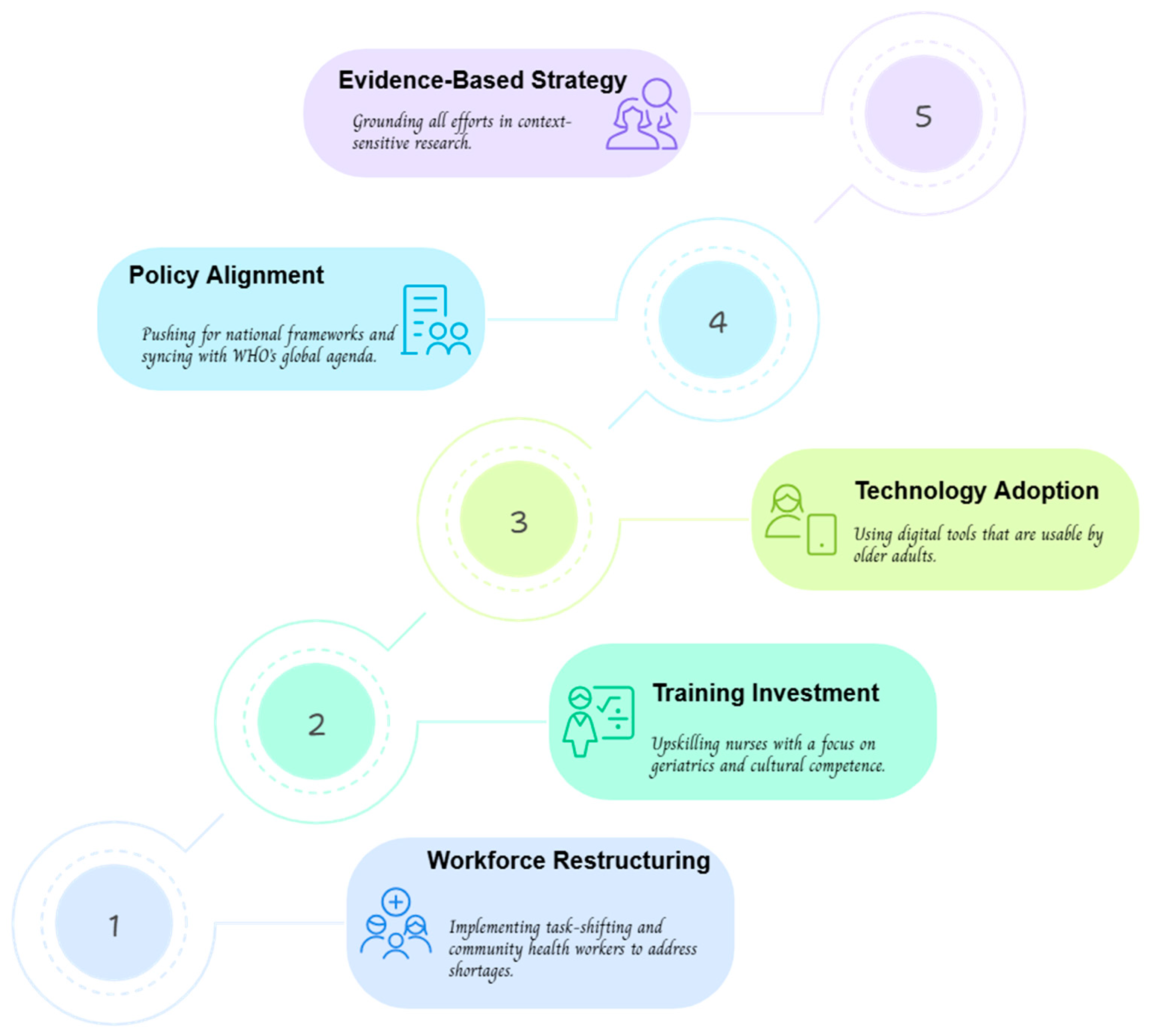

4. Conclusions and Way Forward

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liao, L.; Feng, M.; You, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guan, C.; Liu, Y. Experiences of older people, healthcare providers and caregivers on implementing person-centered care for community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.K.C.; Wong, F.K.Y.; Wong, M.C.S.; Chow, K.K.S.; Kwan, D.K.S.; Lau, D.Y.S. A community-based health–social partnership program for community-dwelling older adults: A hybrid effectiveness–implementation pilot study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ankenbauer, S.A.; Guo, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ma, X.; He, L. Rethinking technological solutions for community-based older adult care: Insights from older partners in China. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2025, 9, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncatar, T.R.T.; Nakamura, K.; Siongco, K.L.L.; Seino, K.; Carlson, R.; Canila, C.C.; Javier, R.S.; Lorenzo, F.M.E. Interprofessional collaboration and barriers among health and social workers caring for older adults: A Philippine case study. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Aro, A.R.; Shrestha, B.; Thapa, S. Elderly care in Nepal: Are existing health and community support systems enough? SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211066381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokorelias, K.M.; Wasilewski, M.B.; Flanagan, A.; Zhabokritsky, A.; Singh, H.; Dove, E.; Eaton, A.D.; Valentine, D.; Sheppard, C.L.; Abdelhalim, R.; et al. Co-creating socio-culturally-appropriate virtual geriatric care for older adults living with HIV: A community-based participatory, intersectional protocol. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231205189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.; Halcomb, E.; Masso, M. The contribution of primary care practitioners to interventions reducing loneliness and social isolation in older people—An integrative review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2023, 37, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoong, S.Q.; Liao, A.W.X.; Goh, S.H.; Zhang, H. Educational effects of community service-learning involving older adults in nursing education: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 113, 105376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waymouth, M.; Siconolfi, D.; Friedman, E.M.; Saliba, D.; Ahluwalia, S.C.; Shih, R.A. Barriers and facilitators to home- and community-based services access for persons with dementia and their caregivers. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2023, 78, 1085–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodsuban, P.; Nuntaboot, K. Community-based flood disaster management for older adults in southern Thailand: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2021, 8, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkimbeng, M.; Han, H.R.; Szanton, S.L.; Alexander, K.A.; Davey-Rothwell, M.; Giger, J.T.; Gitlin, L.N.; Joo, J.H.; Koeuth, S.; Marx, K.A.; et al. Exploring challenges and strategies in partnering with community-based organizations to advance intervention development and implementation with older adults. Gerontologist 2022, 62, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, K.; Sutan, R.; Shahar, S.; Manaf, M.R.A.; Jaafar, M.H.; Abdul Maulud, K.N.; Embong, Z.; Keliwon, K.B. Connecting the dots between social care and healthcare for the sustainability development of older adult in Asia: A scoping review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeydani, A.; Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F.; Hosseini, M.; Zohari-Anboohi, S. Community-based nursing: A concept analysis with Walker and Avant’s approach. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ke, Y.; Sankaran, S.; Xia, B. Problems in the home and community-based long-term care for the elderly in China: A content analysis of news coverage. Int. J. Health Plan. Mgmt. 2021, 36, 1727–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Hussein, M.R.; Utterman, S.; Jushua, J. Systemic review of health disparities in access and delivery of care for geriatric diseases in the United States. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galof, K.; Balantič, Z. Making the decision to stay at home: Developing a community-based care process model for aging in place. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.; Lobchuk, M.; Livingston, P.M.; Layton, N.; Hutchinson, A.M. Informal carers’ support needs, facilitators and barriers in the transitional care of older adults: A qualitative study. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 2876–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP Checklists. 2023. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools. 2020. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Bolton, P.; West, J.; Whitney, C.; Jordans, M.J.; Bass, J.; Thornicroft, G.; Murray, L.; Snider, L.; Eaton, J.; Collins, P.Y.; et al. Expanding mental health services in low-and middle-income countries: A task-shifting framework for delivery of comprehensive, collaborative, and community-based care. Camb. Prism. Glob. Ment. Health 2023, 10, e16. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/43537788DF743160294EE33C618B4D9F/S2054425123000055a.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.M.; Park, Y.H.; Cho, B.; Lim, K.C.; Jang, S.N.; Chang, S.J.; Ko, H.; Noh, E.Y.; Ryu, S.I. Development of a community-based integrated service model of health and social care for older adults living alone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozneak, K.A.; Jindal, S.K.; Munro, S.; Huhn, C.A.; Page, T.; Edes, T.E.; Hartronft, S.R. Lessons from the Department of Veterans Affairs: A continuum of age-friendly care for older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2025, 73, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Hua, W.; Tang, D.; Xu, K.; Xu, Q. A study on supply–demand satisfaction of community-based senior care combined with the psychological perception of the elderly. Healthcare 2021, 9, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishnav, L.M.; Joshi, S.H.; Joshi, A.U.; Mehendale, A.M. The National Programme for Health Care of the Elderly: A review of its achievements and challenges in India. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2022, 26, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csanádi, M.; Kaló, Z.; Rutten-van Molken, M.; Looman, W.; Huic, M.; Ercevic, D.; Atanasijevic, D.; Lorenzovici, L.; Petryszyn, P.; Pogány, G.; et al. Prioritization of implementation barriers related to integrated care models in Central and Eastern European countries. Health Policy 2022, 126, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.F.; Su, Y.Y.; Jhang, K.M.; Chen, C.M. Patterns of home- and community-based services in older adults with dementia: An analysis of the long-term care system in Taiwan. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinman, L.E.; Gasca, A.; Hoeft, T.J.; Raue, P.J.; Henderson, S.; Perez, R.; Huerta, A.; Fajardo, A.; Vredevoogd, M.A.; James, K.; et al. “We are the sun for our community:” Partnering with community health workers/promotores to adapt, deliver and evaluate a home-based collaborative care model to improve equity in access to quality depression care for older US Latino adults who are underserved. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1079319. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler, J.E.; Zmora, R.; Peterson, C.M.; Mitchell, L.L.; Jutkowitz, E.; Duval, S. What interventions keep older people out of nursing homes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 3609–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelman, A.; Guzzardo, M.T.; Antolin Muñiz, M.; Arenas, L.; Gomez, A. Assessing the emergency response role of community-based organizations (CBOs) serving people with disabilities and older adults in Puerto Rico post-hurricane María and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhu, Q.; Lin, S. The implementation of a community-centered first aid education program for older adults—Community health workers perceived barriers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zhang, X.; Huang, R.; Yi, M.; Dong, X.; Li, Z. Barriers to accessing internet-based home care for older patients: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, M.K.; Rosenkoetter, M.; Pacquiao, D.F.; Callister, L.C.; Hattar-Pollara, M.; Lauderdale, J.; Milstead, J.; Nardi, D.; Purnell, L. Guidelines for implementing culturally competent nursing care. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2014, 25, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Type | Number of Studies | High Quality | Moderate Quality | Low Quality | Score Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative (CASP) | 18 | 10 (55.6%) | 6 (33.3%) | 2 (11.1%) | 3–10 |

| Quantitative (JBI) | 16 | 9 (56.3%) | 5 (31.3%) | 2 (12.5%) | 4–11 |

| Outcome | Intervention | Region | Impact | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Independence | Community-based long-term care | Taiwan | 15% improvement in ADL scores | [28] |

| Functional Independence | Aging-in-place care process | Slovenia | 20% increase in functional independence | [17] |

| Psychosocial Well-Being | Community-based senior care | China | 25% improvement in mental health scores | [25] |

| Psychosocial Well-Being | Home-based depression care | USA (Latino) | 30% reduction in depressive symptoms | [29] |

| Reduced Hospital Readmissions | Transitional care programs | Global (Review) | 18% reduction in readmissions | [30] |

| Reduced Hospital Readmissions | Integrated health-social care | South Korea | 22% reduction in readmissions | [23] |

| Aspect | Intervention | Region | Impact | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust-Building | Person-centered nursing | Australia | 40% increase in patient trust | [19] |

| Trust-Building | Cultural competency training | Canada | 32% improvement in trust scores | [6] |

| Trust-Building | Shared decision-making protocols | Netherlands | 38% increase in therapeutic alliance | [27] |

| Trust-Building | Communication enhancement programs | Japan | 28% improvement in trust ratings | [2] |

| Patient Satisfaction | Nurse-led community health programs | India | 35% improvement in satisfaction | [26] |

| Patient Satisfaction | Bedside manner training | United Kingdom | 42% increase in satisfaction scores | [7] |

| Patient Satisfaction | Holistic care approaches | Brazil | 36% improvement in patient experience | [9] |

| Patient Satisfaction | Culturally responsive care | New Zealand | 39% increase in satisfaction ratings | [2] |

| Communication Quality | Active listening training | Germany | 45% improvement in communication scores | [25] |

| Communication Quality | Multilingual support programs | USA | 33% better communication ratings | [29] |

| Communication Quality | Digital communication tools | South Korea | 41% increase in information clarity | [23] |

| Communication Quality | Family-centered communication | France | 37% improvement in care coordination | [27] |

| Empathy and Compassion | Mindfulness-based nursing | Sweden | 44% increase in empathy scores | [17] |

| Empathy and Compassion | Emotional intelligence training | Italy | 31% improvement in compassionate care | [27] |

| Empathy and Compassion | Narrative medicine programs | Mexico | 35% increase in empathetic responses | [6] |

| Care Coordination | Interdisciplinary team meetings | Norway | 48% improvement in care continuity | [27] |

| Care Coordination | Electronic health record integration | Singapore | 43% better care coordination | [3] |

| Care Coordination | Case management protocols | South Africa | 29% improvement in care transitions | [22] |

| Patient Advocacy | Advocacy training programs | Ireland | 46% increase in advocacy behaviors | [19] |

| Patient Advocacy | Ethics committee involvement | Israel | 34% improvement in patient rights protection | [27] |

| Patient Advocacy | Peer support integration | Denmark | 38% increase in patient empowerment | [27] |

| Model | Region | Impact | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Home Visits | USA | 25% reduction in nursing home admissions | [24] |

| Home Visits | Germany | 32% decrease in hospital stays | [19] |

| Home Visits | Australia | 28% improvement in medication adherence | [19] |

| Home Visits | Canada | 35% reduction in care costs | [6] |

| Home Visits | United Kingdom | 22% decrease in adverse events | [7] |

| Home Visits | Netherlands | 30% improvement in quality-of-life scores | [27] |

| Case Management | Taiwan | 15% reduction in emergency visits | [28] |

| Case Management | South Korea | 42% improvement in care coordination | [23] |

| Case Management | Japan | 38% reduction in duplicate services | [2] |

| Case Management | Brazil | 27% decrease in healthcare fragmentation | [9] |

| Case Management | Sweden | 33% improvement in patient satisfaction | [17] |

| Case Management | India | 29% reduction in treatment delays | [26] |

| Transitional Care | Global (Review) | 20% reduction in readmissions | [30] |

| Transitional Care | Italy | 36% decrease in 30-day readmissions | [27] |

| Transitional Care | France | 31% improvement in discharge planning | [27] |

| Transitional Care | Spain | 24% reduction in post-discharge complications | [27] |

| Transitional Care | Norway | 39% improvement in care continuity | [27] |

| Transitional Care | New Zealand | 26% decrease in emergency department visits | [2] |

| Interdisciplinary Teams | Puerto Rico | 85% improved access to care | [31] |

| Interdisciplinary Teams | Finland | 47% improvement in care coordination | [27] |

| Interdisciplinary Teams | Belgium | 52% reduction in communication errors | [27] |

| Interdisciplinary Teams | Israel | 44% increase in treatment adherence | [27] |

| Interdisciplinary Teams | Mexico | 41% improvement in patient outcomes | [6] |

| Interdisciplinary Teams | South Africa | 38% better resource utilization | [22] |

| Nurse-Led Interventions | China | 90% increase in self-efficacy | [32] |

| Nurse-Led Interventions | Denmark | 56% improvement in chronic disease management | [27] |

| Nurse-Led Interventions | Ireland | 63% increase in preventive care uptake | [19] |

| Nurse-Led Interventions | Chile | 48% reduction in symptom severity | [9] |

| Nurse-Led Interventions | Poland | 54% improvement in health literacy | [27] |

| Nurse-Led Interventions | Thailand | 45% increase in self-management behaviors | [10] |

| Technology-Enhanced Care | Singapore | 67% improvement in remote monitoring | [3] |

| Technology-Enhanced Care | Estonia | 51% reduction in missed appointments | [27] |

| Technology-Enhanced Care | South Korea | 58% increase in medication compliance | [23] |

| Technology-Enhanced Care | UAE | 43% improvement in care accessibility | [3] |

| Technology-Enhanced Care | Portugal | 39% reduction in documentation errors | [27] |

| Community-Based Care | Philippines | 72% increase in health screening participation | [4] |

| Community-Based Care | Ghana | 65% improvement in maternal health outcomes | [22] |

| Community-Based Care | Colombia | 49% reduction in preventable hospitalizations | [9] |

| Community-Based Care | Vietnam | 55% increase in vaccination rates | [13] |

| Community-Based Care | Morocco | 41% improvement in chronic disease control | [22] |

| Specialized Geriatric Care | Switzerland | 34% reduction in cognitive decline | [27] |

| Specialized Geriatric Care | Austria | 46% improvement in functional status | [27] |

| Specialized Geriatric Care | Slovenia | 37% decrease in falls incidents | [17] |

| Specialized Geriatric Care | Czech Republic | 42% improvement in nutrition status | [27] |

| Specialized Geriatric Care | Hungary | 29% reduction in polypharmacy issues | [27] |

| Palliative Care Integration | Argentina | 78% improvement in end-of-life comfort | [9] |

| Palliative Care Integration | Turkey | 61% increase in family satisfaction | [27] |

| Palliative Care Integration | Greece | 53% reduction in unnecessary interventions | [27] |

| Palliative Care Integration | Croatia | 47% improvement in pain management | [27] |

| Palliative Care Integration | Romania | 44% increase in home death preference | [27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Espinel-Jara, V.M.; Tapia-Paguay, M.X.; Tito-Pineda, A.P.; López-Aguilar, E.C.; Fernández-Cusimamani, E. Humanized and Community-Based Nursing for Geriatric Care: Impact, Clinical Contributions, and Implementation Barriers. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080302

Espinel-Jara VM, Tapia-Paguay MX, Tito-Pineda AP, López-Aguilar EC, Fernández-Cusimamani E. Humanized and Community-Based Nursing for Geriatric Care: Impact, Clinical Contributions, and Implementation Barriers. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(8):302. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080302

Chicago/Turabian StyleEspinel-Jara, Viviana Margarita, María Ximena Tapia-Paguay, Amparo Paola Tito-Pineda, Eva Consuelo López-Aguilar, and Eloy Fernández-Cusimamani. 2025. "Humanized and Community-Based Nursing for Geriatric Care: Impact, Clinical Contributions, and Implementation Barriers" Nursing Reports 15, no. 8: 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080302

APA StyleEspinel-Jara, V. M., Tapia-Paguay, M. X., Tito-Pineda, A. P., López-Aguilar, E. C., & Fernández-Cusimamani, E. (2025). Humanized and Community-Based Nursing for Geriatric Care: Impact, Clinical Contributions, and Implementation Barriers. Nursing Reports, 15(8), 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080302