The Experience of Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus with the Use of Glucose Monitoring Systems: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

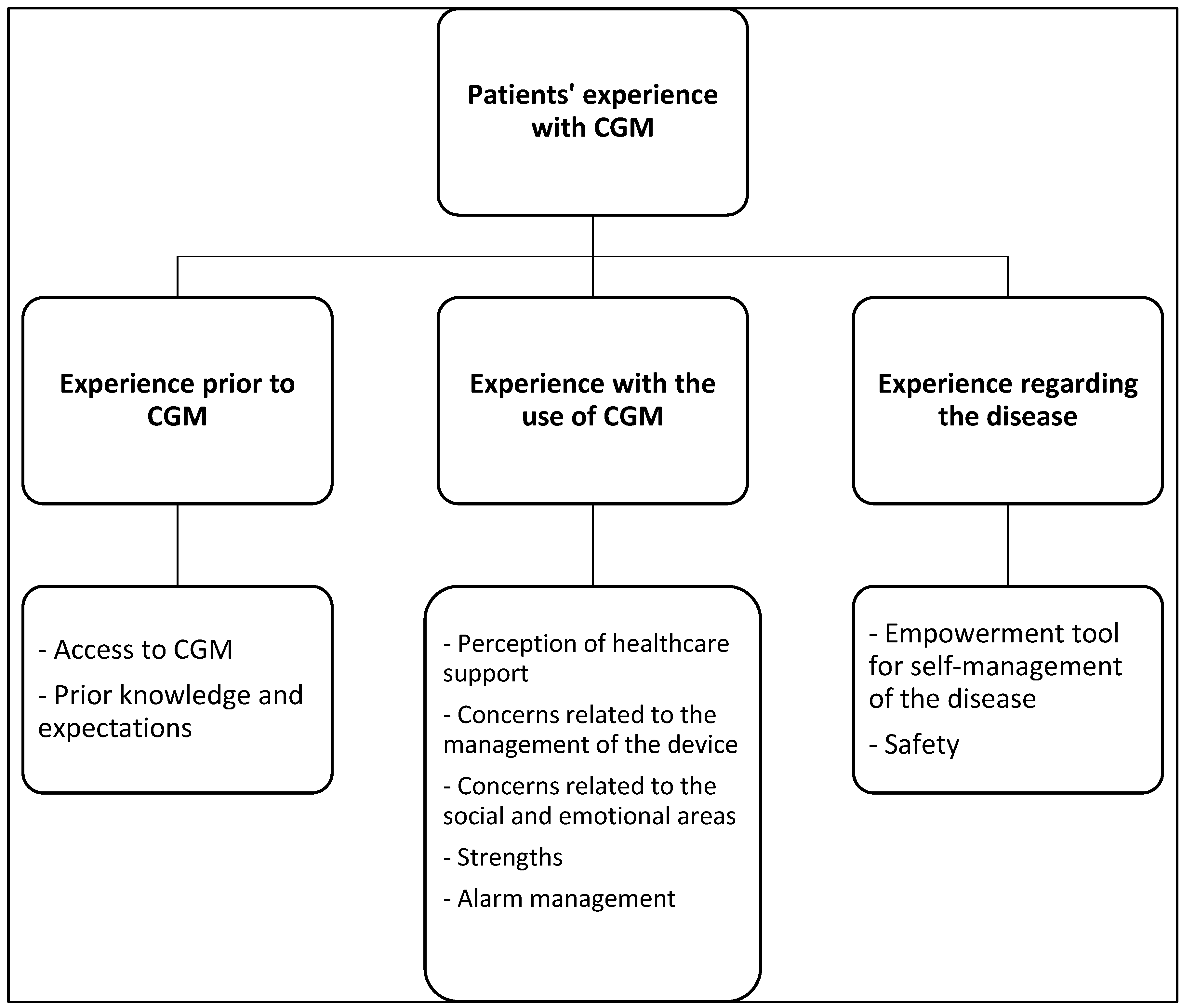

3. Results

- (CGM: continuous glucose monitoring)

- Experience prior to CGM: this theme referred to the information previously received and the knowledge patients already had before their first contact with and use of this device. It also included the factors that, from their perspective, influenced their decision to start using it. In our study, we identified two subthemes:(a) Access to CGM: more than half (six participants) became aware of it through the Endocrinology service, although four participants stated that they learned about it through information from the internet or from other family members/friends who had used it previously:

“… finally, they referred me to the endocrinologist, and the endocrinologist saw that it was diabetes. (…) Then, they sent me to diabetes education, and the first thing they gave me was the sensor.”(Participant 1)

“… I had a friend who had it. Because I used to inject myself and I had many calluses from pricking myself so much every day, because I would prick myself 4 or 5 times a day. (…) A friend told me, let’s see if they can get it for you.”(Participant 4) [Note: resigned and tired tone.]

- One of the patients mentioned that, even though they were not covered by the healthcare system years ago, they always tried to buy one despite its high price:

“… it started to gain attention before the healthcare system included it. From time to time, I would buy one, because logically, my situation wasn’t that great.”(Participant 2)

- (b) Prior knowledge and expectations: for many of the participants, the initial expectations regarding monitoring were that this procedure would promote greater control over their condition, and that they would finally be able to stop using the traditional method of capillary glucose monitoring through finger pricks:

“As long as it meant no more pricks, anything would do.”(Participant 5)

“… maybe it was easier. My fingers hurt a lot already.”(Participant 7)

“If I’m being honest, I just thought, thank goodness I don’t have to prick my fingers.”(Participant 9) [Note: nods and smiles.]

- On the other hand, one participant mentioned that at first, they found this innovative system a bit complicated and challenging:

“Maybe it was going to be a bit of a hassle to use and it was going to be complicated.”(Participant 1) [Note: low voice, long pauses, downward gaze.]

- Experience with the use of CGM: this theme grouped the sensations, perceptions, and data reported by patients once they started using this device for monitoring, including not only the main concerns or fears but also the strengths observed. Additionally, this category contains the perception of the quality of care from the nurse’s perspective. In our study, we identified five subthemes:

- (a) Perception of healthcare support: this category included data involving feelings related to perceived support and the care received from primary and specialized healthcare staff in general, regarding the use and management of the CGM device. All participants rated positively the accessibility they have to the Endocrinology and Nutrition Service in case they have any questions, not only about this device but also regarding uncertainties about their disease treatment. Furthermore, they appreciated that both the endocrinologist and nurse from this unit anticipated events, constantly informing them of how the disease would progress, which helped ensure optimal treatment and management of the situation. Many participants valued the telephone contact with this unit.

“Both the endocrinologist and the nurse made everything crystal clear for me. They took the time to explain the whole process, what was going to happen, and how I would feel. We were always one step ahead. Nothing ever took me by surprise.”(Participant 8)

“… I have a phone number to call for Diabetes Education (…) There’s so much information to process that there are always details that slip through. But I always have that phone number.”(Participant 1)

“… you have easy access to the endocrinologist, they attend to you right away.”(Participant 4) [Note: nods and smiles.]

- On the other hand, all participants reported problems and deficits in primary care centers, as they have limitations regarding the management of sensors, and consider that, being the first line of healthcare, they should be more prepared. The participants indicated that primary care healthcare professionals should be trained and have experience with these systems, which are becoming more common in our society. Additionally, all participants agreed on the importance of primary care healthcare professionals having more knowledge in such a specific and complex area as nutrition in T1DM:

“… In the health center, there’s no one trained. The general practitioner doesn’t understand, and neither do the nurses. Unless they’re specialized in endocrinology, they don’t understand anything.”(Participant 2) [Note: shakes head slowly.]

“In the health center, maybe they don’t have the same training and can’t tell you much. You might end up explaining more about the sensor to them than they explain to you…”(Participant 3) [Note: shrugs.]

- (b) Concerns related to the management of the device: all patients expressed that they felt uneasy about the fear of it failing or the fear of being without it:

“One of the main concerns is the fear that it will fail, you’re afraid it won’t sound the alarm at night.”(Participant 2) [Note: shows general tension on the face.]

“I’m afraid, sometimes when I’m wearing short sleeves, that it might come off or get caught on something.”(Participant 4)

- One of the patients mentioned that they experienced dependency on the device and would check it constantly:

“… I was a bit obsessed with my blood sugar and checked it a lot (…) at first, it was like, all the time, constantly. But you don’t want them to take it away from you. It’s a love-hate relationship.”(Participant 1)

- (c) Concerns related to the social and emotional areas: Four women expressed feeling uncomfortable or discriminated against in certain situations in their daily lives. Notably, one of them associated wearing the device with not being selected for a job position because they were identified as a sick person:

“… I don’t like people seeing it. Especially in a job interview. (…) These are problems. Who wants a problem?”(Participant 2) [Field note: the interviewee avoided eye contact and appeared restless.]

- Other female participants indicated feeling upset about experiencing unpleasant situations in their social context and being forced to explain the continuous glucose monitoring:

“There was a comment near me from a woman who noticed I was wearing it and made a comment like, ‘Oh, you have a disease, right?’.”(Participant 7) [Note: unsure tone, trembling hands.]

“People would ask me in the summer, ‘What’s that you’re wearing?’.”(Participant 10)

- Male participants conveyed that they did not feel observed by others and did not give much importance to it, normalizing the situation:

“At first, I did care if people noticed me, especially at the beach. But now I don’t. Now, I don’t mind wearing three here or four.”(Participant 9)

“I don’t mind if it’s seen. The only thing people say is, ‘What’s that?’ Those who don’t know ask, ‘What is that?’ Now you pay more attention and notice that more people are wearing it.”(Participant 8)

- (d) Strengths: the interviewed patients highlighted as the main strength the fact that they were able to avoid capillary finger pricks:

“I no longer had to prick my finger. The device is not difficult to use.”(Participant 1)

“Not having to constantly prick myself to check my blood sugar.”(Participant 3)

- They also valued having the CGM always with them, as it syncs with their phone, describing it as something that is convenient, hard to forget (unlike the traditional glucometer), easy to use, and promotes autonomy (because it does not require the help or assistance of a third person):

“The old machine, sometimes I’ve forgotten it at home (…) I put it on myself, I got the hang of it, and I don’t find it difficult at all. I understood it well from the first day.”(Participant 5)

“You don’t need third parties to put it on.”(Participant 8)

- Particularly, one of them mentioned that thanks to this innovative system, they feel motivated and eager to participate in different activities:

“With this, I am much better. I look much better. Because before, I didn’t feel like doing anything, I would sit and watch TV, I didn’t go out, and on the days when I could maybe go out, I wouldn’t because I couldn’t.”(Participant 9)

- (e) Alarm management: all the patients acknowledged that the sensor alarms, which alert about high and low blood sugar levels, are a very positive resource for managing the disease:

“They are a peace of mind for me, and they don’t stop until you turn them off.”(Participant 4)

“You get a little bored with them, but they are absolutely necessary and great.”(Participant 6)

“The alarms at night make me feel safer (…) You have a low during the day, and that’s fine, but a low at night, when you end up waking up, and just thinking you don’t know if you’ll wake up…”(Participant 2) [Note: shows soft smile.]

- However, six participants show that they only have the hypoglycemia alert active:

“When I have it high, I’m not using it. Because when it’s high, I inject insulin, and that’s it. I prefer to have it off because if not, it keeps sounding continuously. And I keep the low alarm on because I think it’s more serious.”(Participant 2)

- Although some mentioned that these notifications cause them nervousness and anxiety and that at night they prefer to keep only the low glucose alarm, as they generally consider it absolutely necessary:

“The low glucose alarm, I think it’s important to have it on.”(Participant 1)

“It’s a way to notice that something is happening, although when it suddenly rings, it makes me anxious and I get more nervous.”(Participant 7)

- Only one of them was resistant to all the alarms, even the one that alerts about hypoglycemia, because they felt they perceive and recognize the characteristic symptoms of this situation without relying on the sensor:

“They are disconnected, the endocrinologist had told me that they could even make me a little nervous and that it wasn’t worth it. (…) For now, I recognize hypoglycemia right away. And at night, I prefer to sleep peacefully without the shock of the alarm.”(Participant 10)

- Experience regarding the disease: This includes the sensations and reactions triggered in the patient with CGM and how this device influences the course of their T1DM. The results ranged from empowerment and self-management of the disease to the sense of security in daily life provided by the device:

- (a) Empowerment tool for self-management of the disease: Once the disease is accepted, the patient must adjust to this new situation, a new and unknown scenario for many that they have to adapt to, and which initially seems complicated (as conveyed in other categories as well). All the patients with T1DM in this study considered the CGM as a relief, which reduced their concern and helped them face the disease more effectively. All of this, even though for many of them it was a new reality they had to learn to live with, assuming its potential complications and taking an active role in managing the new condition:

“Having control over glucose, knowing how you are at any moment. If you’re going to exercise, then I have to take something, or I don’t have to take it…”(Participant 10) [Note: nods and smiles.]

- All the subjects made a positive assessment of their progress over time and felt strong enough to achieve a good quality of life despite their chronic illness:

“The comfort of being able to improve my diabetes, to improve the graph, improve my quality of life.”(Participant 2)

“… It makes life so much easier for the user. It helps with better control of diabetes. (…) It’s much easier and more continuous.”(Participant 6)

“… This was a lifesaver… I never thought it would be so useful and valuable to me. For me, it’s the best thing that could have happened.”(Participant 9)

- All of them indicated that this technology favored greater self-control of the disease and improved their blood sugar levels, making their daily life easier. They considered the CGM a unique strategy for managing out-of-range glucose levels, applying their knowledge to achieve optimal blood sugar values again:

“If I see that it’s rising, then I correct it. I mean, it’s telling me what I need to do all the time.”(Participant 1) [Note: with a confident tone.]

“It makes my day-to-day life easier. Every so often, I check the app to see if I’m doing well. (…) It’s a big step forward because it helps me a lot.”(Participant 8)

- (b) Safety: the participants stated that the constant information provided by this device gives them great security, and they feel calmer regarding the risk of experiencing hypoglycemia:

“I’m more insecure without the sensor.”(Participant 1)

“At night, if you have hypoglycemia and you’re using another system, maybe you keep sleeping (…) with the sensor, you wake up or you wake up.”(Participant 6) [Note: with a confident tone.]

“You relax, so to speak, because you know you have it, you know if you’re going to have a hypo or a hyper. (…) I think you live more peacefully.”(Participant 8)

- The patients, regardless of their age, were aware that they were being monitored and felt more secure and protected:

“I’m more calm, I know it’s there, I feel safe.”(Participant 7)

“It’s not the first time that (…) it alerted me at 4 or 5 in the morning that I was low, and otherwise, I wouldn’t have noticed.”(Participant 4)

- The greatest fear they revealed was the risk of hypoglycemia at night, which is why the vast majority highlighted that the main benefit of the sensor is that it alerts them if they experience nocturnal hypoglycemia. This is what gives them the greatest sense of security with this device.

“You have a low during the day, and that’s fine, but a low at night, when you end up waking up, and just thinking you don’t know if you’ll wake up…”(Participant 2)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/atlas/tenth-edition/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Diabetes Technology: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45 (Suppl. 1), S113–S124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olczuk, D.; Priefer, R. A history of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) in self-monitoring of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Síndrome 2018, 12, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritholz, M.D.; Henn, O.; Atakov Castillo, A.; Wolpert, H.; Edwards, S.; Fisher, L.; Toschi, E. Experiences of adults with type 1 diabetes using glucose sensor-based mobile technology for glycemic variability: Qualitative study. JMIR Diabetes 2019, 4, e14032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, P.; Chen, S.; Chow, C.K.; Cheung, N.W.; Martinez-Martin, D.; Caillaud, C.; Scholes-Robertson, N.; Kelly, A.; Craig, J.C.; Strippoli, G.; et al. Patient experiences of continuous glucose monitoring and sensor-augmented insulin pump therapy for diabetes: A systematic review of qualitative studies. J. Diabetes 2023, 15, 1048–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, M.L.N.; Gamaza, P.F.; Gil, L.D. Diabetes Mellitus y monitorización continua de la glucosa. Intervención e Investigación en Contextos Clínicos y de la Salud: Visiones Actuales Basadas en la Evidencia; Asociación Universitaria de Educación y Psicología (ASUNIVEP): Almería, Spain, 2022; pp. 339–345. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez de Vera-Gómez, P.; Mateo-Rodríguez, C.; Vivas-López, C.; Serrano-Olmedo, I.; Méndez-Muros, M.; Morales-Portillo, C.; Jiménez, M.S.; Hernández-Herrero, C.; Martínez-Brocca, M.A. Effectiveness of a flash glucose monitoring systems implementation program through a group and telematic educational intervention in adults with type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 2022, 69, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante Gomez, E. La perspectiva ricoeuriana y el análisis de las narrativas. Fundam. Humanidades 2013, 1, 175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wirihana, L.; Welch, A.; Williamson, M.; Christensen, M.; Bakon, S.; Craft, J. Using Colaizzi’s method of data analysis to explore the experiences of nurse academics teaching on satellite campuses. Nurse Res. 2018, 25, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.; Stadler, M.; Ismail, K.; Amiel, S.; Herrmann-Werner, A. Are patients with diabetes mellitus satisfied with technologies used to assist with diabetes management and coping?: A structured review. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2014, 16, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vloemans, A.F.; van Beers, C.A.J.; de Wit, M.; Cleijne, W.; Rondags, S.M.; Geelhoed-Duijvestijn, P.H.; Kramer, M.H.H.; Serné, E.H.; Snoek, F.J. Staying safe: Continuous glucose monitoring in people with type 1 diabetes and impaired hypoglycemia awareness—A qualitative study. Diabet. Med. 2017, 34, 1470–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson-Lewis, C.; Darville, G.; Mercado, R.E.; Howell, S.; Di Maggio, S. MHealth technology use and implications in historically underserved and minority populations in the United States: Systematic literature review. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2018, 6, e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Flor, M.; Jansà-Morató, M.; Galindo-Rubio, M.; Penalba-Martínez, M. Factors associated to adherence to blood glucose self-monitoring in patients with diabetes treated with insulin. The dapa study. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 2018, 65, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Holtz, B.; Lauckner, C. Diabetes management via mobile phones: A systematic review. Telemed. e-Health 2012, 18, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overend, L.; Simpson, E.; Grimwood, T. Qualitative analysis of patient responses to the ABCD FreeStyle Libre audit questionnaire. Pract. Diabetes 2019, 36, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veazie, S.; Winchell, K.; Gilbert, J.; Paynter, R.; Ivlev, I.; Eden, K.B.; Nussbaum, K.; Weiskopf, N.; Guise, J.-M.; Helfand, M. Rapid Evidence Review of Mobile Applications for Self-management of Diabetes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosta, L.; Menyhart, A.; Mahmeed, W.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Al-Alawi, K.; Banach, M.; Banerjee, Y.; Ceriello, A.; Cesur, M.; Cosentino, F.; et al. Telemedicine for diabetes management during COVID-19: What we have learnt, what and how to implement. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1129793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, B.; Doral-Yagüe, E.; Lugones-Sánchez, C.; Velasco-Martin, V.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, A. Situación de la especialidad de enfermería familiar y comunitaria en Castilla y León. RqR Quant. Qual. Community Nurs. Res. 2023, 11, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hervás, A.; Zabaleta, A.; De Miguel, G.; Beldarráin, O.; Díez, J. Health related quality of life in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2007, 30, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, M.J.; Münzenmayer, B.; Osorio, T.; Arancibia, M.; Madrid, E. Sintomatología depresiva y control metabólico en pacientes ambulatorios portadores de diabetes mellitus tipo 2. Rev. Med. Chile 2018, 146, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, F.; Inzunza, C.; Ovalle, C.; Ventura, T. Diabetes mellitus tipo 1 y psiquiatría infantojuvenil. Rev. Chil. Pediatría 2009, 80, 467–474. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Unanua, M.P.; López-Simarro, F.; Novillo-López, C.I.; Olivares-Loro, A.G.; Yáñez-Freire, S. Diabetes y mujer, ¿por qué somos diferentes? Semergen 2024, 50, 102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, N.C.; Beck, R.W.; Miller, K.M.; Clements, M.A.; Rickels, M.R.; Di Meglio, L.A.; Maahs, D.M.; Tamborlane, W.V.; Bergenstal, R.; Smith, E.; et al. State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016–2018. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2019, 21, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toschi, E.; Fisher, L.; Wolpert, H.; Love, M.; Dunn, T.; Hayter, G. Evaluating a glucose-sensor-based tool to help clinicians and adults with type 1 diabetes improve self-management skills. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2018, 12, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritholz, M.D.; Beste, M.; Edwards, S.S.; Beverly, E.A.; Atakov-Castillo, A.; Wolpert, H.A. Impact of continuous glucose monitoring on diabetes management and marital relationships of adults with type 1 diabetes and their spouses: A qualitative study. Diabet. Med. 2014, 31, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickup, J.C.; Ford, H.M.; Samsi, K. Real-time continuous glucose monitoring in type 1 diabetes: A qualitative framework analysis of patient narratives. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question | Objective |

|---|---|

| How did you first learn about the continuous glucose monitoring device? | Explore the origin of knowledge about the device and initial impressions. |

| Did you accept being a user of this device right away or did you have any doubts? | Analyze the initial reactions and possible barriers to accepting the device. |

| What were your expectations of this sensor? | Identify the user’s expectations prior to using the sensor. |

| Were those expectations met? | Assess whether the device met the user’s expectations. |

| What is the most positive aspect of this sensor? | Highlight the beneficial aspects of the sensor from the user’s perspective. |

| What is the most negative aspect of this sensor? | Identify any negative points or areas for improvement according to the user. |

| What concerns did you have about using this sensor? | Address any worries or concerns prior to using the sensor. |

| What was the easiest part of using this sensor? | Determine what aspects of use were intuitive or simple. |

| And what was the most difficult? | Explore the challenges or difficulties encountered while using the device. |

| Do you think the support received from healthcare professionals was sufficient? | Evaluate the quality and adequacy of the support provided by healthcare professionals. |

| What do you think of the sensor alarms? | Investigate the user’s perception of the alarms, their usefulness, and possible drawbacks. |

| Would you improve any aspect of the sensor? | Gather suggestions for improvements or innovations based on the user’s experience. |

| Particpant | Sex | Age | Level of Studies | Employment Status | Marital Status | Lives Alone | Time Since Diagnosis | Time Wearing the Sensor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Woman | 49 | University | Active | Single | Yes | 1 year | 7 months |

| 2 | Woman | 50 | Primary | Active | Married | No | 22 years | 3 years |

| 3 | Woman | 47 | Primary | Active | Married | No | 18 years | 2 years |

| 4 | Man | 69 | Primary | Retired | Widowed | Yes | 25 years | 8 months |

| 5 | Woman | 63 | Primary | Retired | Married | No | 30 years | 3 years |

| 6 | Man | 49 | University | Pensioner | Single | Yes | 20 years | 2 years |

| 7 | Woman | 56 | Primary | Active | Divorced | No | 5 years | 2 years |

| 8 | Man | 42 | Secondary | Active | Single | No | 7 months | 7 months |

| 9 | Man | 61 | Primary | Retired | Married | No | 35 years | 1 year |

| 10 | Woman | 50 | University | Active | Married | No | 1 year | 6 months |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soto-Rodriguez, A.; Fernández-Conde, A.; Leirós-Rodríguez, R.; Opazo, Á.T.; Martinez-Blanco, N. The Experience of Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus with the Use of Glucose Monitoring Systems: A Qualitative Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080294

Soto-Rodriguez A, Fernández-Conde A, Leirós-Rodríguez R, Opazo ÁT, Martinez-Blanco N. The Experience of Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus with the Use of Glucose Monitoring Systems: A Qualitative Study. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(8):294. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080294

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoto-Rodriguez, Anxela, Ana Fernández-Conde, Raquel Leirós-Rodríguez, Álvaro Toubes Opazo, and Nuria Martinez-Blanco. 2025. "The Experience of Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus with the Use of Glucose Monitoring Systems: A Qualitative Study" Nursing Reports 15, no. 8: 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080294

APA StyleSoto-Rodriguez, A., Fernández-Conde, A., Leirós-Rodríguez, R., Opazo, Á. T., & Martinez-Blanco, N. (2025). The Experience of Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus with the Use of Glucose Monitoring Systems: A Qualitative Study. Nursing Reports, 15(8), 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080294