Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health in Nursing Students and Non-Nursing Students: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Materials

2.1.1. Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21; [27]): German Version [28,29]

2.1.2. Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10; [30]): German Adaption [31]

2.1.3. Questionnaire on Mental Stress and Strain [32]

2.2. Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease of 2019 |

| PhD | Doctor of Philosophy |

| Care4Stress | 7-week app-based passive psychoeducation stress-management program |

| CHES | Computer-based Health Evaluation System |

| DASS-21 | Depression Anxiety Stress Scales |

| PSS-10 | Perceived Stress Scale-10 |

| BGW | German Social Accident Insurance Institution for the Health and Welfare Services |

| SPSS 26 | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| (M)ANOVA | (Multivariate) Analysis of Variance |

References

- Heuse, S.; Risius, U.-M. Stress bei Studierenden mit und ohne Nebenjob. Prävention Gesundheitsförderung 2022, 17, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.N.; Chiu, H.-Y.; Chuang, Y.-H.; Huang, H.-C. Prevalence of Stress and Anxiety Among Nursing Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Nurse Educ. 2023, 48, E90–E95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admi, H.; Moshe-Eilon, Y.; Sharon, D.; Mann, M. Nursing students’ stress and satisfaction in clinical practice along different stages: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 68, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrague, L.J.; McEnroe-Petitte, D.M.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Edet, O.B.; Tsaras, K.; Leocadio, M.C.; Colet, P.; Kleisiaris, C.F.; Fradelos, E.C.; Rosales, R.A.; et al. Stress and coping strategies among nursing students: An international study. J. Ment. Health 2018, 27, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pick, P.; Brüggemann, J.; Grote, C.; Grünhagen, E.; Lampert, T. Schwerpunktbericht der Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes: Pflege; Robert Koch-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Schmedes, C. Emotionsarbeit in der Pflege; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterbuchner, K.; Zuschnegg, J.; Lirussi, R.; Windhaber, T.; Archan, T.; Kadric, I. Geringe Attraktivität des Pflegeberufs bei Auszubildenden: COVID-19 hat die Belastungen verschärft. ProCare 2021, 26, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, H.; Pekince, H. Nursing students’ views on the COVID-19 pandemic and their perceived stress levels. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Ji, B.; Lio, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Ge, Y.; Xie, Y.; Liu, C. The prevalence of psychological stress in student populations during the COVID-19 epidemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyadi, M.; Tonapa, S.I.; Luneto, S.; Lin, W.-T.; Lee, B.-O. Prevalence of mental health problems and sleep disturbances in nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 57, 103228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, Z.; Wilcox, H.; Leung, L.; Dearsley, O. COVID-19 and the mental well-being of Australian medical students: Impact, concerns and coping strategies used. Australas. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mheidly, N.; Fares, M.Y.; Fares, J. Coping with Stress and Burnout Associated with Telecommunication and Online Learning. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 574969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zyl, L.E.; Rothmann, S.; Zondervan-Zwijnenburg, M.A. Longitudinal trajectories of study characteristics and mental health before and during the COVID-19 lockdown. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 633533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wen, W.; Zhang, H.; Ni, J.; Jiang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Ye, L.; Feng, F.; Ge, Z. Anxiety, depression, and stress prevalence among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 71, 2123–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ashry, A.M.; Harby, S.S.; Ali, A.A.G. Clinical stressors as perceived by first-year nursing students of their experience at Alexandria main university hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2022, 41, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majrashi, A.; Khalil, A.; Al Nagshabandi, E.; Majrashi, A. Stressors and Coping Strategies among Nursing Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.X.; Jiao, J.R.; Hao, W.N. Stress levels of nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2022, 101, e30547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büttner, T.R.; Dlugosch, G.E. Stress im Studium. Prävention Gesundheitsförderung 2013, 8, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, K.L.; Shumaker, C.J.; Yearwood, E.L.; Crowell, N.A.; Riley, J.B. Perceived stress and social support in undergraduate nursing students’ educational experiences. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.L.; Taylor, H.; Nelson, J.D. Comparison of Mental Health Characteristics and Stress Between Baccalaureate Nursing Students and Non-Nursing Students. J. Nurs. Educ. 2016, 55, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black Thomas, L.M. Stress and depression in undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Nursing students compared to undergraduate students in non-nursing majors. J. Prof. Nurs. 2022, 38, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Learned helplessness. Annu. Rev. Med. 1972, 23, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, T.H.; Begjani, J.; Arman, A.; Hoseini, A.S.S. The concept analysis of helplessness in nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A hybrid model. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 6782–6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.M.; Staggl, S.; Holzner, B.; Rumpold, G.; Dresen, V.; Canazei, M. Preventive Effect of a 7-Week App-Based Passive Psychoeducational Stress Management Program on Students. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LimeSurvey GmbH. LimeSurvey: An Open Source Survey Tool. Available online: https://www.limesurvey.org (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Holzner, B.; Giesinger, J.M.; Pinggera, J.; Zugal, S.; Schöpf, F.; Oberguggenberger, A.S.; Gamper, E.M.; Zabernigg, A.; Weber, B.; Rumpold, G. The Computer-based Health Evaluation Software (CHES): A software for electronic patient-reported outcome monitoring. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2012, 12, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety & Stress Scales, 2nd ed.; Psychology Foundation: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilges, P.; Essau, C. Die Depressions-Angst-Stress-Skalen. Schmerz 2015, 29, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilges, P.; Essau, C. DASS. Depressions-Angst-Stress-Skalen—Deutschsprachige Kurzfassung; ZPID: Trier, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E.E.; Schönfelder, S.; Domke-Wolf, M.; Wessa, M. Measuring stress in clinical and nonclinical subjects using a German adaptation of the Perceived Stress Scale. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2020, 20, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kersten, M.; Meyer, A. Mitarbeiterbefragung: Psychische Belastung und Beanspruchung: BGW Miab für Die Pflege und den Stationären Wohnbereich der Behindertenhilfe. Berufsgenossenschaft Für Gesundheitsdienst und Wohlfahrtspflege, Hamburg, Germany, 2002. Available online: https://www.bgw-online.de/resource/blob/9328/b5d037949d1740517c4fa0cde1db627c/bgw08-00-110-mitarbeiterbefragung-download-data.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Tung, Y.-J.; Lo, K.K.H.; Ho, R.C.M.; Tam, W.S.W. Prevalence of depression among nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 63, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Haj, M.; Allain, P.; Annweiler, C.; Boutoleau-Bretonnière, C.; Chapelet, G.; Gallouj, K.; Kapogiannis, D.; Roche, J.; Boudoukha, A.H. High exhaustion in geriatric healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 second lockdown. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 83, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, A.; Laurent, A.; Lheureux, F.; Ribeiro-Marthoud, M.A.; Ecarnot, F.; Binquet, C.; Quenot, J.-P. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of professionals in 77 hospitals in France. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślusarska, B.; Nowicki, G.J.; Niedorys-Karczmarczyk, B.; Chrzan-Rodak, A. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in nurses during the first eleven months of the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsby, E.; Goldsby, M.; Neck, C.B.; Neck, C.P. Under pressure: Time management, self-leadership, and the nurse manager. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.; Dalgleish, L.; Bucknall, T.; Estabrooks, C.; Hutchinson, A.M.; Fraser, K.; de Vos, R.; Binnekade, J.; Barrett, G.; Saunders, J. The effects of time pressure and experience on nurses’ risk assessment decisions: A signal detection analysis. Nurs. Res. 2008, 57, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, C.I.; Hsiao, F.J.; Chou, T.A. Nurse-perceived time pressure and patient-perceived care quality. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broetje, S.; Jenny, G.J.; Bauer, G.F. The key job demands and resources of nursing staff: An integrative review of reviews. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffington, A.; Zwink, J.; Fink, R.; DeVine, D.; Sanders, C. Factors affecting nurse retention at an academic Magnet® hospital. J. Nurs. Adm. 2012, 42, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamisa, N.; Oldenburg, B.; Peltzer, K.; Ilic, D. Work Related Stress, Burnout, Job Satisfaction and General Health of Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, J.; Jackson, D.; Usher, K. Compassion fatigue in critical care nurses: An integrative review of the literature. Saudi Med. J. 2019, 40, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano García, G.; Ayala Calvo, J.C. Emotional exhaustion of nursing staff: Influence of emotional annoyance and resilience. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2012, 59, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzorou, M.; Koukia, E. Professional burnout of geriatric nurses caring for elderly people with dementia. Perioper. Nurs. (GORNA) 2018, 7, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcella, J.; Kelley, M.L. “Death is part of the job” in long-term care homes: Supporting direct care staff with their grief and bereavement. Sage Open 2015, 5, 2158244015573912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, C. Stress, coping, and burn-out in nursing students. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryer, J.; Cherkis, F.; Raman, J. Health-promotion behaviors of undergraduate nursing students: A survey analysis. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2013, 34, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernomas, W.M.; Shapiro, C. Stress, depression, and anxiety among undergraduate nursing students. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2013, 10, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, L.M.; Oliviera, E.L.; Pinheiro, I.S. Psychiatric disorders in nursing students. Rev. Enferm. UFPE Line 2014, 8, 4320–4329. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, J.; Roxburgh, M.; Taylor, J.; Lauder, W. An integrative literature review of student retention in programmes of nursing and midwifery education: Why do students stay? J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 1372–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryjmachuk, S.; Richards, D.A. Predicting stress in pre-registration nursing students. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2007, 12 Pt 1, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochford, C.; Connolly, M.; Drennan, J. Paid part-time employment and academic performance of undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2009, 29, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curva, M.D.P.; Dela Pena, C.V.; Gueco, L.A.; Martinez, J.C.S.; Martinez, M.I.L.; Faller, E.M. Prolonged Working Hours and Stress Responses among Nurses: A Review. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2023, 4, 2176–2179. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, I.; Söderström, M.; Rudman, A.; Dahlgren, A. Under pressure—Nursing staff’s perspectives on working hours and recovery during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2024, 7, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoedl, M.; Bauer, S.; Eglseer, D. Influence of nursing staff working hours on stress levels during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional online survey. HeilberufeScience 2021, 12, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitsky, B.; Findling, Y.; Ereli, A.; Hendel, T. Anxiety and coping strategies among nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 46, 102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokar, Z.; Bijani, M.; Haghshenas, H. Explaining the challenges faced by nursing students in clinical learning environments during the post-COVID era: A qualitative content analysis. BMC Res. Notes 2025, 18, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Godoy, M.D.; Teixeira da Costa, E.; Salas, M.G.; Lara, A.P.; Bernal, N.C.; Domínguez, B.M.; Gago-Valiente, F.J. Challenges in Clinical Training for Nursing Students during COVID-19: Examining Its Effects on Nurses’ Job Satisfaction. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 2024, 7865540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, J.; Davey, Z.; Wood, C.; Dawson, P.; Papiez, K.; Kelly, D.; Watts, T.; Rafferty, A.M.; Henshall, C.; Watson, E.; et al. Impact of nurse education prior to and during COVID-19 on nursing students’ preparedness for clinical placement: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2024, 7, 100260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hösl, B.; Oberdorfer, H.; Niedermeier, M.; Kopp, M. Sport specialization and burnout symptoms among adolescent athletes. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2025, 30, 2460626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryuwat, P.; Holmgren, J.; Asp, M.; Radabutr, M.; Lövenmark, A. Experiences of Nursing Students Regarding Challenges and Support for Resilience during Clinical Education: A Qualitative Study. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 1604–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.M.; Harder, M.; Staggl, S.; Holzner, B.; Dresen, V.; Canazei, M. Evaluation of the effectiveness of a 7-week minimal guided and unguided cognitive behavioral therapy-based stress-management APP for students. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, A.C.; Götz, T.; Pekrun, R. Emotionen. In Pädagogische Psychologie; Wild, E., Möller, J., Eds.; Springer-Lehrbuch: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 201–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.C.R.; Silva, W.R.; Maroco, J.; Campos, J.A.D.B. Escala de Estresse Percebido Aplicada a Estudantes Universitárias: Estudo de Validação. Psychol. Community Health 2015, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.M.; Brähler, E.; Dreier, M.; Reinecke, L.; Müller, K.W.; Schmutzer, G.; Wölfling, K.; Beutel, M.E. The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale—Psychometric characteristics in a representative German community sample. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobelski, G.; Naylor, K.; Kobelska, A.; Wysokiński, M. Stress among Nursing Students in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C.; Querido, A.; Sousa, P.; Dixe, M.A. Assessment and Psychometric Properties of the 21-Item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) among Portuguese Higher Education Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 2546–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Arbués, E.; Gea-Caballero, V.; Granada-López, J.M.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Pellicer-García, B.; Antón-Solanas, I. The Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and Stress and Their Associated Factors in College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, R.; Best, T.; Williams, S.; Vandelanotte, C.; Irwin, C.; Heidke, P.; Saito, A.; Rebar, A.L.; Dwyer, T.; Khalesi, S. Associations between health behaviors and mental health in Australian nursing students. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 53, 103084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittayapun, Y.; Summart, U.; Polpanadham, P.; Direksunthorn, T.; Paokanha, R.; Judabood, N.; Zulfatul A’la, M. Validation of depression, anxiety, and stress scales (DASS-21) among Thai nursing students in an online learning environment during the COVID-19 outbreak: A multi-center study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Non-Nursing Students (n = 291) | Nursing Students (n = 154) | Total (n = 445) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | Minimum | 18 | 16 | 16 |

| Maximum | 46 | 62 | 62 | |

| Mean (SD) | 22.43 (3.61) | 27.7 (10.99) | 24.25 (7.5) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | Female | 223 (77) | 116 (75) | 339 (76) |

| Male | 65 (22) | 38 (25) | 103 (23) | |

| Gender diverse | 3 (1) | 0 | 3 (1) | |

| Marital status | Single/divorced/ widowed | 200 (69) | 81 (53) | 281 (63) |

| Married/with a life partner | 91 (31) | 73 (47) | 164 (37) | |

| Level of education | Bachelor | 247 (85) | - | - |

| Master | 39 (13) | - | - | |

| PhD | 5 (2) | - | - | |

| University courses | Psychology | 217 (75) | - | - |

| Other courses | 74 (25) | - | - | |

| Working-hours/week | <10 h | - | 4 (3) | - |

| 10–19 h | - | 5 (3) | - | |

| 20–29 h | - | 10 (6) | - | |

| >30 h | - | 135 (88) | - | |

| Children | Yes | 3 (1) | 43 (28) | 46 (10) |

| No | 288 (99) | 111 (72) | 399 (90) | |

| Number of children | No children 1–2 children ≥3 children | 288 3 - | 111 35 8 | 399 38 8 |

| Smoking | Yes | 33 (11) | 59 (38) | 92 (21) |

| No | 258 (89) | 95 (62) | 353 (79) | |

| Alcohol consumption | Yes | 57 (20) | 23 (15) | 80 (18) |

| No | 234 (80) | 131 (85) | 365 (82) | |

| Current or past mental illness | Yes | 34 (12) | 26 (17) | 60 (14) |

| No | 257 (88) | 128 (83) | 385 (86) | |

| Current or past physical illness | Yes | 26 (9) | 38 (25) | 64 (14) |

| No | 265 (91) | 116 (75) | 381 (86) | |

| Psychological/psychotherapeutic/psychiatric treatment | Current | 48 (17) | 14 (9) | 62 (14) |

| Past | 62 (21) | 56 (36) | 118 (27) | |

| No | 181 (62) | 84 (55) | 265 (59) |

| Non-Nursing Students (n = 291) | Nursing Students (n = 154) | Total (n = 445) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

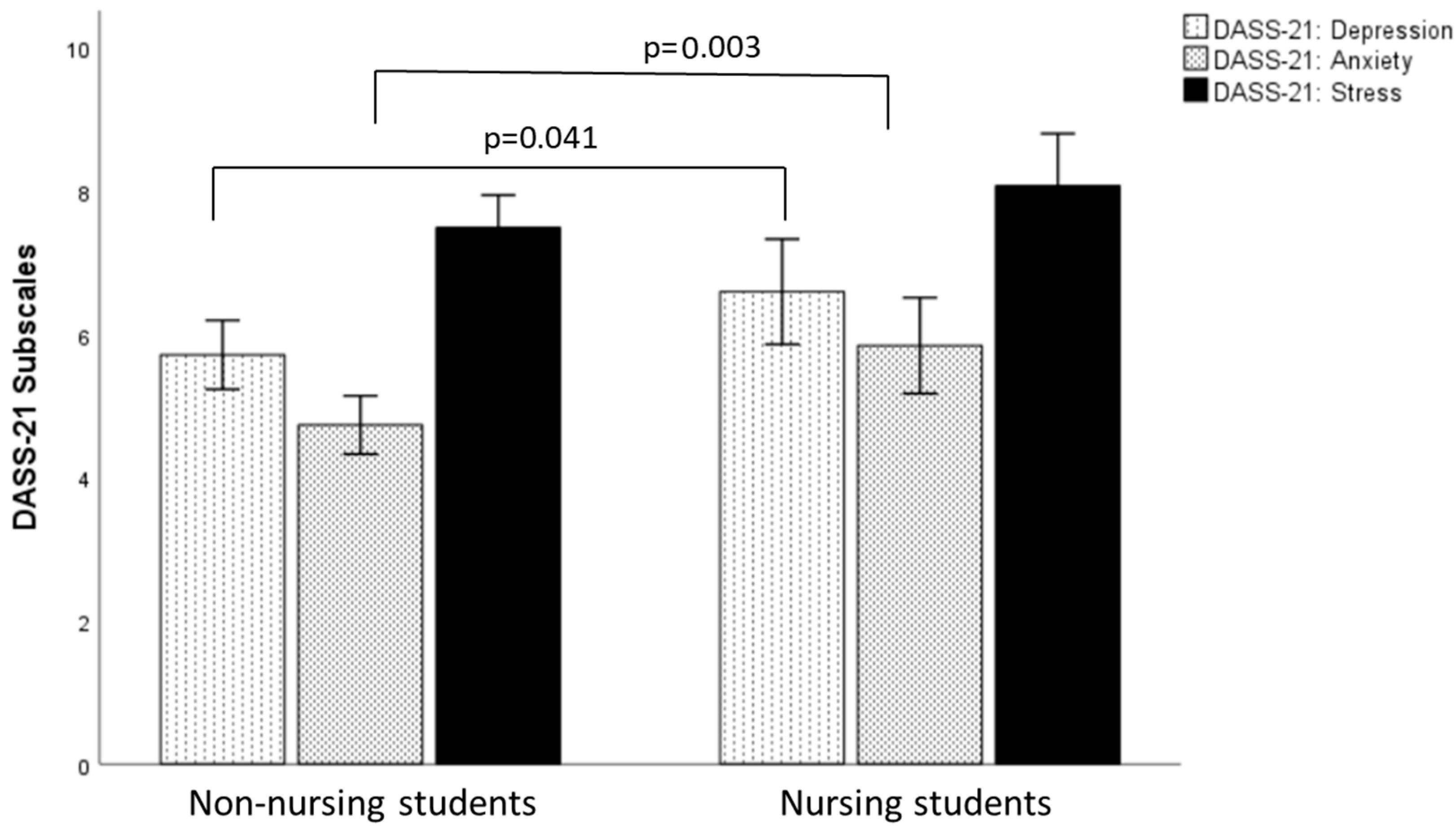

| DASS-21 | Depression | 5.72 | 4.18 | 6.60 | 4.62 | 6.02 | 4.35 |

| Anxiety | 4.74 | 3.53 | 5.84 | 4.21 | 5.12 | 3.81 | |

| Stress | 7.49 | 3.95 | 8.08 | 4.57 | 7.69 | 4.18 | |

| PSS-10 Global Score | 29.10 | 6.47 | 30.82 | 5.86 | 29.69 | 6.32 | |

| PSS-10 Helplessness | 18.12 | 4.32 | 19.20 | 4.29 | 18.50 | 4.34 | |

| PSS-10 Self-efficacy | 13.08 | 2.76 | 12.38 | 2.59 | 12.81 | 2.72 | |

| Helplessness | Self-Efficacy | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 154) | (n = 154) | |

| Mental Stress | ||

| Quantitative workload | 0.272 ** | −0.166 * |

| Qualitative workload | 0.235 ** | −0.084 |

| Work organization | 0.132 | −0.079 |

| Social work climate | 0.226 ** | −0.141 |

| Non-work situation | 0.329 ** | −0.278 ** |

| Mental strain | ||

| Emotional symptoms | 0.708 ** | −0.457 ** |

| Health impairment | 0.550 ** | −0.506 ** |

| Age | Number of Children | Working Hours | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DASS-21 | |||

| Depression | −0.213 ** | 0.129 | 0.194 * |

| Anxiety | −0.254 ** | −0.099 | 0.148 |

| Stress | −0.121 | 0.079 | 0.201 * |

| PSS-10 | |||

| Helplessness | −0.136 | 0.075 | 0.237 ** |

| Self-efficacy | 0.202 * | 0.207 | −0.193 * |

| Global score | −0.184 * | −0.057 | 0.244 ** |

| Mental Stress | |||

| Quantitative workload | 0.013 | −0.107 | 0.056 |

| Qualitative workload | −0.152 | −0.069 | −0.007 |

| Work organization | 0.116 | 0.284 | 0.083 |

| Social work climate | 0.165 * | −0.008 | −0.031 |

| Non-work situation | 0.090 | −0.107 | 0.168 * |

| Mental Strain | |||

| Emotional symptoms | −0.142 | −0.139 | 0.145 |

| Health impairment | −0.076 | 0.063 | 0.205 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dresen, V.; Sigmund, L.; Staggl, S.; Holzner, B.; Rumpold, G.; Fischer-Jbali, L.R.; Canazei, M.; Weiss, E. Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health in Nursing Students and Non-Nursing Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080286

Dresen V, Sigmund L, Staggl S, Holzner B, Rumpold G, Fischer-Jbali LR, Canazei M, Weiss E. Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health in Nursing Students and Non-Nursing Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(8):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080286

Chicago/Turabian StyleDresen, Verena, Liliane Sigmund, Siegmund Staggl, Bernhard Holzner, Gerhard Rumpold, Laura R. Fischer-Jbali, Markus Canazei, and Elisabeth Weiss. 2025. "Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health in Nursing Students and Non-Nursing Students: A Cross-Sectional Study" Nursing Reports 15, no. 8: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080286

APA StyleDresen, V., Sigmund, L., Staggl, S., Holzner, B., Rumpold, G., Fischer-Jbali, L. R., Canazei, M., & Weiss, E. (2025). Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health in Nursing Students and Non-Nursing Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nursing Reports, 15(8), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080286