Perspectives of Refugees from Ukraine on Cultural Identity and Health Care Experiences During U.S. Resettlement

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Health Concerns of Refugees

1.1.2. Challenges and Adaptations in Resettlement

1.2. Theoretical Concepts

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Considerations

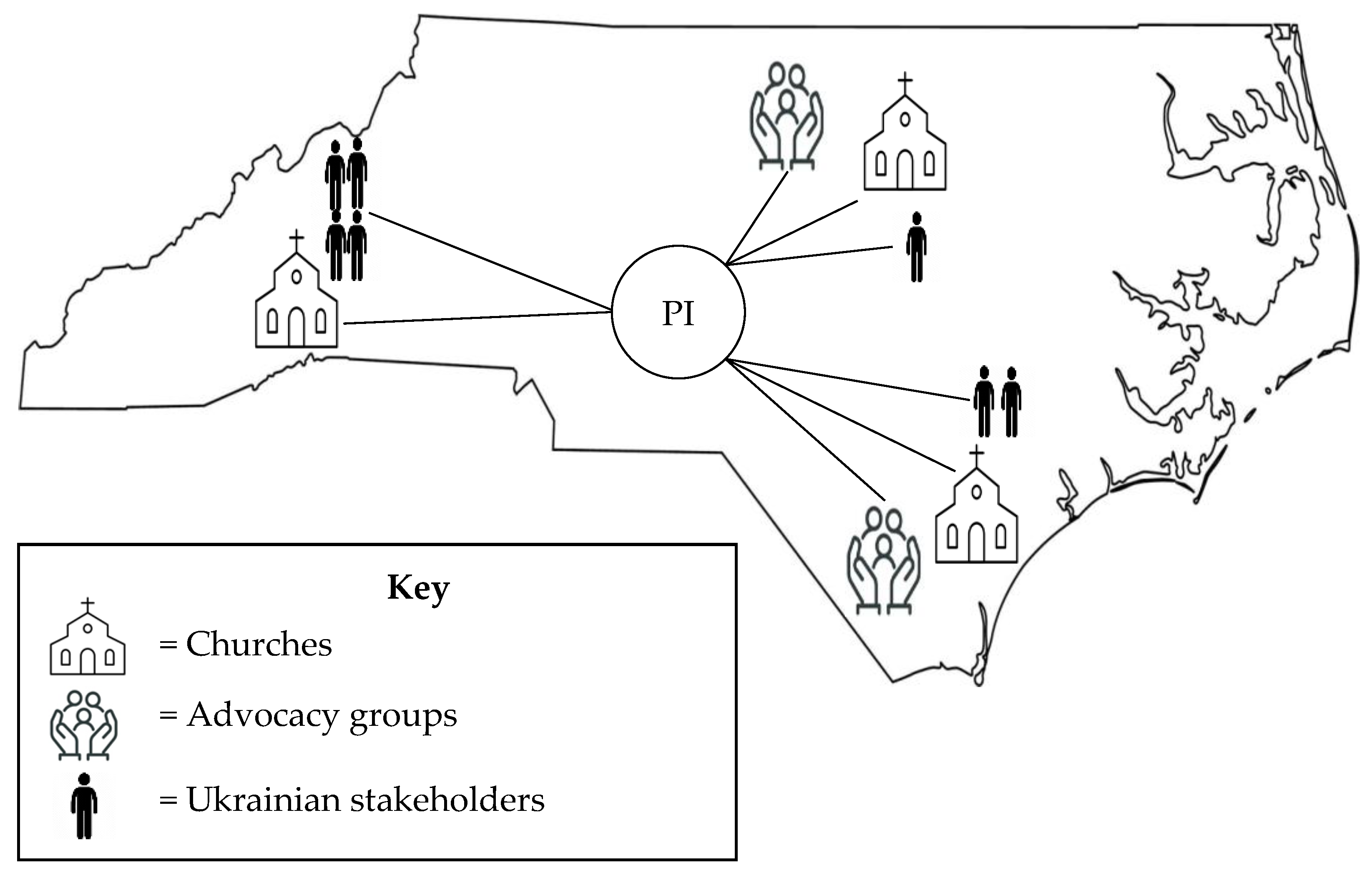

2.3. Study Setting

2.4. Recruitment Strategy and Sample

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Management and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Troubled Health Care Partnerships

3.1.1. Relationships with U.S. Clinicians

For myself, I choose a doctor in Ukraine and it’s my doctor. Like main doctor, family doctor. And this is the person I trust for many years… and she says [Ukrainian doctor], you need to do the list of analysis and then when I go to doctor [United States], he called [and said] half of that list, you don’t need that. You just don’t need that. And I was like well I ask you to do this because my main doctor told me to do this. And I was refused, and it was not once, it was [multiple] times… She [Ukrainian doctor] recommended… You need to tell you have pain there and you have all the symptoms. I mean, it’s strange when you are going to doctor, and you need to lie to get all you need.(FG 4)

…it was unusual for us, when they said to remove wisdom teeth that had not yet grown. Well, it was the first time I’d ever seen that. To remove something that’s not there yet, and it’s like… no problem. We asked for an X-ray. And we consulted a doctor in Ukraine because I knew nothing about it, and the doctor said that there is such a practice and do it, and according to the x-ray, he also recommended it. And we had the operation, and we are happy with it.(FG 1)

Participant 2: My mother used to be a nurse. Now she’s doing other stuff. So we practice evidential medicine. So, we don’t have any traditions or practices. Just pills, just doctors, just analysis.(FG 4)

Participant 3: Yeah, and she [grandmother, a nurse] was a lover of like unconventional medicine, like taking herbs or something. And I was my grandma experiment. And she was healing me with all this, you know untraditional things and it was very good… So, I have a lot of touch with untraditional medicine and maybe that’s why I choose for my kids, homeopathic remedies.(FG 4)

3.1.2. Navigating the U.S. Health Care System

Because, of course, it’s easier to get to a doctor [in Ukraine]. I can choose a doctor. I have a choice… but here it’s so hard. You need to wait; you need to be covered by insurance. So, it’s a big difference… It’s easy to change doctors [in Ukraine].(FG 2)

The program of medical guarantees in Ukraine actually provides you with guaranteed medical care for free which [the] government pays through the National Health Service. But the difference here [in the United States] [between] Medicaid and Medicare and [the] program of medical guarantees in Ukraine is the Medicaid is like about the level of income you have in family. In Ukraine, it doesn’t matter how much you make, you still qualify for health services, basic packages.(FG 3)

I want to say the medicine in the United States is too expensive. But in Ukraine, we have the best… dentists, doctors, I am sure. I’m sure. I will do my teeth only in Ukraine. It’s a yes and in Ukraine we have free primary care. I can go to the doctor; I can choose doctor. I can take blood test. I can get a… Ultrasounds free and it’s a big difference. It’s amazing.(FG 2)

3.2. Imprecise Notions of Preventive Practices

3.2.1. A Self-Driven Ukrainian Approach to Prevention

So, I would say that preventive medicine is very popular in Ukraine. And if you want to see any doctor… You can just easily in that day or maybe the second day you can easily find the doctor and go get anything you want. If you want [an] MRI, you go and do [an] MRI and it won’t cost you a lot. I mean, in America, it will cost you probably like, I don’t know, $10,000.(FG 4)

People are used to cook[ing] home food. So it’s tradition to cook home food… We have a lot of walkways [in Ukraine] and you can easily get anywhere. You know when I’m walking in America, I feel like after zombie apocalypse because there’s no one [around].(FG 4)

When is it too bad, when it’s time to cut something off, they pay attention [in the United States]. In Ukraine, I go to the doctor and ask how I can prevent the development, and this is the most important thing for me.(FG 2)

3.2.2. A Systems-Driven U.S. Approach to Prevention

If they offer me to do some examinations according to my age, as a preventive measure, I agree to it, because I know that in America, I already understand that there is a system here, that they do everything to prevent all this. In Ukraine, they usually don’t do that. If there is a problem, [that is when] they go.(FG 1)

Of course, there are some advantages in American medicine, some advantages, we see that, but there is a lot that is not familiar to us. In Ukraine, we are used to getting to the doctor faster… Here it is a little more difficult, and we have to shift to this system, that it has to be done in advance, that it has to be done regularly, once a year, several times a year, to visit that doctor. We need to shift a little bit.(FG 1)

When we came here, the people we lived with helped us. They helped us to register our children for school, to draw up documents, and the church helped a lot. There were also volunteer organizations all over the place (in the city they live in) that helped with food and the first necessary things that were needed for everyday life.(FG 1)

And I lived with them [sponsors] during seven months here when I came. And [the] church that they are attending… they fundraised money to pay for my tickets [to] the USA. And then this organization they helped me to apply to all documents… Some of my [U.S.] friends they gave me a car… Ukrainian community helped me when I moved in this apartment. They helped me with some small things like plates, cups, some kitchen towels for first time.(FG 3)

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Nursing Research, Practice, and Education

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UNHCR | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

| U.S. | United States |

| U4U | Uniting for Ukraine |

| USCIS | United States Citizenship and Immigration Services |

| GBV | Gender-based violence |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| FGD | Focus group discussions |

| PI | Principal investigator |

| UMCIRB | University and Medical Center Institutional Review Board |

| NC | North Carolina |

| KWIC | Key word in context approach |

| FG | Focus group |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| MARTTI | My Accessible Real-Time Trusted Interpreter |

References

- Operational Data Portal. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Available online: https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/ukraine/ukraine-humanitarian-needs-and-response-plan-2025-april-2025-enuk (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- CBS News. Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/ukrainian-refugees-us-uniting-for-ukraine-russia-invasion/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Ukrainian Immigration Task Force. Available online: https://ukrainetaskforce.org/uscis-officially-pauses-new-uniting-for-ukraine-u4u-applications-until-further-notice/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Cambridge University Press. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/cultural-identity#google_vignette (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Oviedo, L.; Seryczyńska, B.; Torralba, J.; Roszak, P.; Del Angel, J.; Vyshynska, O.; Muzychuk, I.; Churpita, S. Coping and resilience strategies among Ukraine war refugees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, S.; Granberg, M.; Nilsson, T. Love thy (Ukrainian) neighbour: Willingness to help refugees depends on their origin and is mediated by perceptions of similarity and threat. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 63, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrodzka, M.; McMahon, G.; Griffin, S.M.; Muldoon, O.T. New social identities in Ukrainian ‘refugees’: A social cure or social curse? Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 353, 117048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahim, H.F.; Mooren, T.T.M.; Knipscheer, J.W.; Chung, J.M.; Laceulle, O.M.; Boelen, P.A. Temporal associations between cultural identity conflict and psychological symptoms among Syrian young adults with refugee backgrounds: A four-wave longitudinal study. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2025, 16, 2511524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldamen, Y. Social media, digital resilience, and knowledge sustainability: Syrian refugees’ perspectives. J. Intercult. Commun. 2025, 25, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, C.M.; Steiner, J.J.; Kappas Mazzio, A.; Bagwell-Gray, M.; Wachter, K.; Johnson-Agbakwu, C.; Messing, J.; Nizigiyimana, J. Sexual and reproductive healthcare needs of refugee women exposed to gender-based violence: The case for trauma-informed care in resettlement contexts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalouhi, J.; Currow, D.C.; Dumit, N.Y.; Sawleshwarkar, S.; Glass, N.; Stanfield, S.; Digiacomo, M.; Davidson, P.M. The health and well-being of women and girls who are refugees: A case for action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostiuk, O.; Shunko, Y.; Jusiene, R.; Breidokiene, R.; Drejeriene, V.; Lesinkiene, S.; Valiulis, A. Postpartum depression in Ukrainian refugee women who gave birth abroad after beginning of large-scale war. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 32, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Loboda, A. Systematic review of health and disease in Ukrainian children highlights poor child health and challenges for those treating refugees. Acta Paediatr. 2022, 111, 1341–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awuah, W.A.; Ng, J.C.; Mehta, A.; Yarlagadda, R.; Khor, K.S.; Abdul-Rahman, T.; Hussain, A.; Kundu, M.; Sen, M.; Hasan, M.M. Vulnerable in silence: Pediatric health in the Ukrainian crisis. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 82, 104369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badanta, B.; Márquez De la Plata-Blasco, M.; Lucchetti, G.; González-Cano-Caballero, M. The social and health consequences of the war for Ukrainian children and adolescents: A rapid systematic review. Public Health 2024, 226, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maternik, M.; Andrunevych, R.; Drożdż, D.; Czauderna, P.; Grenda, R.; Tkaczyk, M. Transition and management of Ukrainian war refugee children on kidney replacement therapy. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2023, 38, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawłowicz-Szlarska, E.; Vanholder, R.; Sever, M.S.; Tuğlular, S.; Luyckx, V.; Eckardt, K.; Gallego, D.; Ivanov, D.; Nistor, I.; Shroff, R.; et al. Distribution, preparedness and management of Ukrainian adult refugees on dialysis—An international survey by the renal disaster relief task force of the European renal association. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, 2407–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanyk, N.; Hromovyk, B.; Levytska, O.; Agh, T.; Wettermark, B.; Kardas, P. The impact of the war on maintenance of long-term therapies in Ukraine. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1024046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caglevic, C.; Rolfo, C.; Gil-Bazo, I.; Cardona, A.; Sapunar, J.; Hirsch, F.R.; Gandara, D.R.; Morgan, G.; Novello, S.; Garassino, M.; et al. The armed conflict and the impact on patients with cancer in Ukraine: Urgent considerations. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2022, 8, e220012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lushchak, O.; Velykodna, M.; Bolman, S.; Strilbytska, O.; Berezovskyi, V.; Storey, K.B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among Ukrainians after the first year of Russian invasion: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg. Health 2024, 36, 100773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karstoft, K.; Bjørndal, L.D.; Pedersen, A.A.; Korchakova, N.; Power, S.A.; Morton, T.A.; Koushede, V.J.; Thøgersen, M.H.; Hall, B.J. Associations of war exposures, post-migration living difficulties and social support with (complex) PTSD: A cohort study of Ukrainian refugees resettled in Denmark. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 376, 118080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adedeji, A.; Kaltenbach, S.; Metzner, F.; Kovach, V.; Rudschinat, S.; Arrizabalaga, I.M.; Buchcik, J. Mental health outcomes among female Ukrainian refugees in Germany—A mixed method approach exploring resources and stressors. Healthcare 2025, 13, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokun, O. The Ukrainian population’s war losses and their psychological and physical health. J. Loss Trauma 2023, 28, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Dorta, W.; Marrero-González, C.; Díaz-Hernández, E.; Brito-Brito, P.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, D.; Colichón, O.R.; Martín-García, A.; Pavés-Lorenzo, E.; Rodríguez-Santos, M.; García-Cabrera, J.; et al. Identification of health needs in Ukrainian refugees seen in a primary care facility in Tenerife, Spain. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.; Stewart, H.L.N.; Mohan, R.; Poudel-Tandukar, K.; Aldulaimi, S.; DiVito, B.; Alaofè, H. “Nobody does checkups back there”: A qualitative study of refugees’ healthcare needs in the United States from stakeholders’ perspectives. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardas, P.; Mogilevkina, I.; Aksoy, N.; Ågh, T.; Garuoliene, K.; Lomnytska, M.; Istomina, N.; Urbanaviče, R.; Wettermark, B.; Khanyk, N. Barriers to healthcare access and continuity of care among Ukrainian war refugees in Europe: Findings from the RefuHealthAccess study. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1516161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childress, S.; Shrestha, N.; Russ, S.; Berge, J.; Roy, K.; Lewin, A.; Perez-Brena, N.; Feinberg, M.; Halfon, N. A qualitative study of adaptation challenges of Ukrainian refugees in the United States. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2025, 169, 108039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davitian, K.; Noack, P.; Eckstein, K.; Hübner, J.; Ahmadi, E. Barriers of Ukrainian refugees and migrants in accessing German healthcare. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, N.; Smithwick, E.; Murphy, E.; Jennings, A.A. The challenges experienced by Ukrainian refugees accessing general practice: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Fam. Pract. 2025, 42, cmaf012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewtak, K.; Kanecki, K.; Tyszko, P.; Goryński, P.; Kosińska, I.; Poznańska, A.; Rząd, M.; Nitsch-Osuch, A. Hospitalizations of Ukrainian migrants and refugees in Poland in the time of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, K.L.; Choufani, M.R.; Płaszewska-Żywko, L. An educational approach to develop intercultural nursing care for refugees from Ukraine: A qualitative study. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2024, 72, e13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iellamo, A.; Wong, C.M.; Bilukha, O.; Smith, J.P.; Ververs, M.; Gribble, K.; Walczak, B.; Wesolowska, A.; Al Samman, S.; O’Brien, M.; et al. “I could not find the strength to resist the pressure of the medical staff, to refuse to give commercial milk formula”: A qualitative study on effects of the war on Ukrainian women’s infant feeding. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1225940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artzi-Medvedik, R.; Tsikholska, L.; Chertok, I.A. A qualitative exploration of the experience of child feeding among Ukrainian refugee and immigrant mothers during escape and relocation. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2024, 38, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfanash, H.A.; Almagharbeh, W.T.; Alnawafleh, K.A. Effects of the Syrian refugee crisis on public health and healthcare services in Jordan: A systematic review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2025, 72, e70040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, P.; Heggen, H.; Vase, E.B.; Sandal, G.M. Cultural tightrope walkers: A qualitative study of being a young refugee in quest for identity and belonging in Norway. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, J.; Nigbur, D. Lived experiences of Sri Lankan Tamil refugees in the UK: Migration and identity. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 63, 1547–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. Available online: https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience (accessed on 30 May 2025).[Green Version]

- Andrushko, Y.; Lanza, S.T. Exploring resilience and its determinants in the forced migration of Ukrainian citizens: A psychological perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidi, E.; Tosti, A.E.; Meringolo, P.; Hatalskaya, H.; Chiodini, M. Hearing the voices of Ukrainian refugee women in Italy to enhance empowerment interventions. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2025, 75, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudel-Tandukar, K.; Davis, C.; Mosijchuk, Y.; Poudel, K.C. Social and emotional well-being intervention to reduce stress, anxiety, and depression among Ukrainian refugees resettled in Massachusetts. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2024, 70, 1461–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baran, M.; Grzymała-Moszczyńska, H.; Zjawińska, M.; Sugay, L.; Pujszo, I.; Ovsiienko, Y.; Naritsa, V.; Niedziałek, J.; Boczkowska, M. Superhero in a skirt: Psychological resilience of Ukrainian refugee women in Poland: A thematic analysis. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2024, 24, 100506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leininger, M. Culture care theory: A major contribution to advance transcultural nursing knowledge and practices. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2002, 13, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarland, M.R.; Wehbe-Alamah, H.B. Leininger’s Culture Care Diversity and Universality: A Worldwide Nursing Theory, 3rd ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland, M.R.; Wehbe-Alamah, H.B. Leininger’s theory of culture care diversity and universality: An overview with a historical retrospective and a view toward the future. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2019, 30, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikberg, A.; Eriksson, K. Intercultural caring-An abductive model. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2008, 22, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingram, R.R. Using Campinha-Bacote’s process of cultural competence model to examine the relationship between health literacy and cultural competence. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorne, S. Interpretive Description Qualitative Research for Applied Practice, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, R.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 5th ed.; SAGE: Riverside, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Choufani, M.R.; Larson, K.L. Cultural Perspectives of Ukrainian Nurses Living in the United States: A Pilot Focused Ethnography. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2025, submitted.

- Murukutla, N.; Puri, P. A Guide to Conducting Online Focus Groups; Vital Strategies: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis, 4th ed.; SAGE: Riverside, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design, 4th ed.; SAGE: Riverside, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; SAGE: Riverside, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Marconi, V.C. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorne, S. Untangling the misleading message around saturation in qualitative nursing studies. Nurse Author Ed. 2020, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawry, L.L.; Korona-Bailey, J.; Juman, L.; Janvrin, M.; Donici, V.; Kychyn, I.; Maddox, J.; Koehlmoos, T.P. A qualitative assessment of Ukraine’s trauma system during the Russian conflict: Experiences of volunteer healthcare providers. Confl. Health 2024, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/16-05-2024-primary-health-care-in-ukraine--improving-health-services-amid-the-war-and-beyond (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Kohlenberger, J.; Buber-Ennser, I.; Pędziwiatr, K.; Rengs, B.; Setz, I.; Brzozowski, J.; Riederer, B.; Tarasiuk, O.; Pronizius, E. High self-selection of Ukrainian refugees into Europe: Evidence from Kraków and Vienna. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolke, K.; Walter, J.; Weckbecker, K.; Münster, E.; Tillmann, J. Identifying gaps in healthcare: A qualitative study of Ukrainian refugee experiences in the German system, uncovering differences, information and support needs. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandenberger, J.; Tylleskär, T.; Sontag, K.; Peterhans, B.; Ritz, N. A systematic literature review of reported challenges in health care delivery to migrants and refugees in high-income countries—The 3C model. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, K.L.; Płaszewska-Żywko, L.; Sira, N.; Leibowitz, J. Nursing praxis on intercultural care with war-affected refugees. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2025, 12, 23333936251336109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank Blogs. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/world-bank-country-classifications-by-income-level-for-2024-2025 (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Koyama, J.; Turan, A. Coloniality and refugee education in the United States. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitterfeld, L.; Ozkaynak, M.; Denton, A.H.; Normeshie, C.A.; Valdez, R.S.; Sharif, N.; Caldwell, P.A.; Hauck, F.R. Interventions to improve health among refugees in the United States: A systematic review. J. Community Health 2025, 50, 130–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holod, A.F.; Tornwall, J.; Teall, A.M.; Overcash, J. Competency in trauma-informed care: Empowering advanced practice registered nursing students to adopt a trauma-informed approach during routine health assessment. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 144, 106477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieślak, I.; Jaworski, M.; Panczyk, M.; Barzykowski, K.; Majda, A.; Theofanidis, D.; Gotlib-Małkowska, J. Multicultural personality profiles and nursing student attitudes towards refugee healthcare workers: A national, multi-institutional cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today 2024, 134, 106094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/381329/9789240110236-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 30 May 2025).

| Characteristic | FG1 (n = 3) | FG2 (n = 2) | FG3 (n = 4) | FG4 (n = 3) | Total (N = 12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 12 |

| Age | |||||

| 25–34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 35–54 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 10 |

| 55–65 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Time in United States | |||||

| Less than 1 year | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 1–2 years | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| >2 years | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Preferred language | |||||

| Ukrainian | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| English | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Russian | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Mix: Ukr., Eng., Rus. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| Single | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Divorced | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Preferred religion | |||||

| Baptist/Protestant | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Catholic | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Other: Orthodox Christian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| None | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Highest educational level | |||||

| Finished 12th grade | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Vocational training | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| College-level degree | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 10 |

| Employment | |||||

| Full-time | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Part-time | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Unemployed | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choufani, M.R.; Larson, K.L.; Prannik, M.Y. Perspectives of Refugees from Ukraine on Cultural Identity and Health Care Experiences During U.S. Resettlement. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070263

Choufani MR, Larson KL, Prannik MY. Perspectives of Refugees from Ukraine on Cultural Identity and Health Care Experiences During U.S. Resettlement. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(7):263. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070263

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoufani, Marianne R., Kim L. Larson, and Marina Y. Prannik. 2025. "Perspectives of Refugees from Ukraine on Cultural Identity and Health Care Experiences During U.S. Resettlement" Nursing Reports 15, no. 7: 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070263

APA StyleChoufani, M. R., Larson, K. L., & Prannik, M. Y. (2025). Perspectives of Refugees from Ukraine on Cultural Identity and Health Care Experiences During U.S. Resettlement. Nursing Reports, 15(7), 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070263