Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Content Validity of a Modified Italian Version of the Jackson/Cubbin Pressure Injury Risk Assessment Scale for ICU Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Measurement Instrument

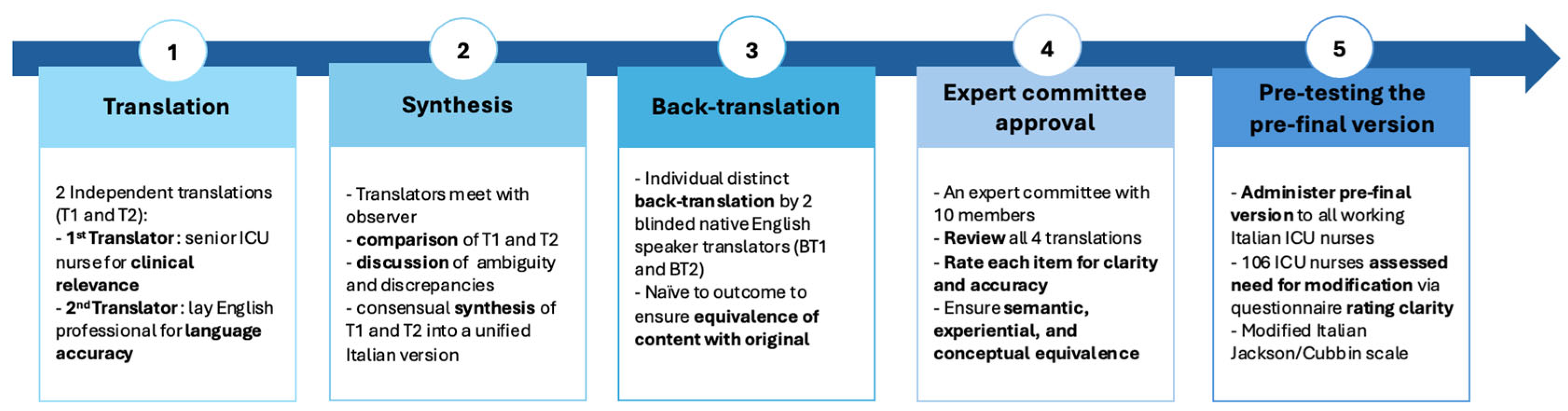

2.3. Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation

2.4. Content Validity

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation

- Age

- 2.

- Weight/Tissue Viability

- 3.

- PMH—Past Medical History/Affecting Condition

- 4.

- Mental State

- 5.

- Mobility

- 6.

- Inotrope

- 7.

- Respiration

- 8.

- Oxygen Requirement

- 9.

- Nutrition

- 10.

- Incontinence

3.2. Pre-Test of the Pre-Final Version

- To include, under each scoring level, a list of comorbid conditions that promote the development of pressure injuries.

- To assign a specific number of comorbidities to each scoring level in order to reduce interpretation variability.

3.3. Content Validity

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| CVI | Content Validity Index |

| S-CVI | Scale-level Content Validity Index |

References

- Labeau, S.O.; Afonso, E.; Benbenishty, J.; Blackwood, B.; Boulanger, C.; Brett, S.J.; Calvino-Gunther, S.; Chaboyer, W.; Coyer, F.; Deschepper, M.; et al. Prevalence, associated factors and outcomes of pressure injuries in adult intensive care unit patients: The DecubICUs study. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Serrano, M.; González Méndez, M.I.; Carrasco Cebollero, F.M.; Lima Rodríguez, J.S. Risk factors for pressure ulcer development in Intensive Care Units: A systematic review. Med. Intensiv. 2017, 41, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderden, J.; Rondinelli, J.; Pepper, G.; Cummins, M.; Whitney, J. Risk factors for pressure injuries among critical care patients: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 71, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP); National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP); Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA). Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Quick Reference Guide; Haesler, E., Ed.; 2019; Available online: http://51.15.64.204/static/pdfs/Quick_Reference_Guide-10Mar2019.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Pazzini, A.; Biselli, B.; Vannini, C.; Fabbri, E.; Falabella, F.; Santandrea, M.G.; Marziliano, M.; Gagliardi, N.; Di Giandomenico, S.; Scotto di Minico, S.; et al. Quali sono i fattori di rischio per le lesioni da pressione in terapia intensiva? Uno studio retrospettivo osservazionale in una terapia intensiva italiana. Scenar.®—II Nurs. Nella Sopravvivenza 2024, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yongde, A. Risk factors for medical device-related pressure injury in ICU patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.J.; Hu, F.H.; Zhang, W.Q.; Tang, W.; Ge, M.; Shen, W.; Chen, H. Incidence, prevalence and risk factors of device-related pressure injuries in adult intensive care unit: A meta-analysis of 10,084 patients from 11 countries. Wound Repair. Regen. 2023, 31, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burston, A.; Miles, S.J.; Fulbrook, P. Patient and carer experience of living with a pressure injury: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 3233–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, N.; Maiti, R.; Aloweni, F.A.B.; Yi Zhen, N.; Yuh, A.S.; Bishnoi, P.; Chong, T.T.; Carmody, D.; Harding, K. Retrospective matched cohort study of incidence rates and excess length of hospital stay owing to pressure injuries in an Asian setting. Health Care Sci. 2023, 2, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.P.; Shen, H.W.; Cai, J.Y.; Zha, M.L.; Chen, H.L. The relationship between pressure injury complication and mortality risk of older patients in follow-up: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Wound J. 2019, 16, 1533–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Durrant, L.; Hutchinson, M.; Ballard, C.; Neville, S.; Usher, K. Living with multiple losses: Insights from patients living with pressure injury. Collegian 2018, 25, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, S.; Campbell, J.; Walker, R.M.; Byrnes, J.; Chaboyer, W. Pressure injuries in Australian public hospitals: A cost of illness study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 130, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Shen, J.; Chen, X.; Wen, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Lao, Y. Value of pressure injury assessment scales for patients in the intensive care unit: Systematic review and diagnostic test accuracy meta-analysis. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2021, 64, 103009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Fernández, F.P.; Pancorbo-Hidalgo, P.L.; Agreda, J.J. Predictive capacity of risk assessment scales and clinical judgment for pressure ulcers: A meta-analysis. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2014, 41, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, S.; Vermillion, B.; Newton, C.; Fall, M.; Li, X.; Kaewprag, P.; Moffatt-Bruce, S.; Lenz, E.R. Predictive validity of the Braden scale for patients in intensive care units. Am. J. Crit. Care 2013, 22, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Yu, T.; Hu, A. Predicting the Risk for Hospital-Acquired Pressure Ulcers in Critical Care Patients. Crit. Care Nurse 2017, 37, e1–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Wu, L.; Chen, Y.; Fu, Q.; Chen, W.; Yang, D. Predictive Validity of the Braden Scale for Pressure Ulcer Risk in Critical Care: A Meta-Analysis. Nurs. Crit. Care 2020, 25, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehicic, A.; Burston, A.; Fulbrook, P. Psychometric properties of the Braden scale to assess pressure injury risk in intensive care: A systematic review. Intensive Crit. Care Nur. 2024, 83, 103686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adibelli, S.; Korkmaz, F. Pressure injury risk assessment in intensive care units: Comparison of the reliability and predictive validity of the Braden and Jackson/Cubbin scales. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 4595–4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delawder, J.M.; Leontie, S.L.; Maduro, R.S.; Morgan, M.K.; Zimbro, K.S. Predictive Validity of the Cubbin-Jackson and Braden Skin Risk Tools in Critical Care Patients: A Multisite Project. Am. J. Crit. Care 2021, 30, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubbin, B.; Jackson, C. Trial of a pressure area risk calculator for intensive therapy patients. Intensive Care Nurs. 1991, 7, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C. The revised Jackson/Cubbin Pressure Area Risk Calculator. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 1999, 15, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Diao, D.; Ye, L. Predictive validity of the Jackson–Cubbin scale for pressure ulcers in intensive care unit patients: A meta-analysis. Nurs. Crit. Care 2023, 28, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Scandrett, K.; Coombe, A.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; Steyerberg, E.; Takwoingi, Y.; Veličković, V.M.; Dinnes, J. Accuracy and clinical effectiveness of risk prediction tools for pressure injury occurrence: An umbrella review. PLoS Med. 2025, 22, e1004518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Lv, L.; Zhang, H.; Tao, H.; Pei, J.; Ma, Y.; Han, L. Comparing the Waterlow and Jackson/Cubbin pressure injury risk scales in intensive care units: A multi-centre study. IWJ 2023, 21, e14602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T.; Owen, S.V. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, M.R. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs. Res. 1986, 35, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebapci, A.; Tilki, R. The effect of vasopressor agents on pressure injury development in intensive care patients. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2024, 83, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippolito, M.; Cortegiani, A.; Biancofiore, G.; Caiffa, S.; Corcione, A.; Giusti, G.D.; Iozzo, P.; Lucchini, A.; Pelosi, P.; Tomasoni, G.; et al. The prevention of pressure injuries in the positioning and mobilization of patients in the ICU: A good clinical practice document by the Italian Society of Anesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation and Intensive Care (SIAARTI). J. Anesth. Analg. Crit. Care 2022, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palese, A. Strumenti di misura, validità e affidabilità: Guida minima alla valutazione critica delle scale. Scenar.®—II Nurs. Nella Sopravvivenza 2018, 28, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Fleiss’ κ | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.78 | Substantial agreement |

| 2 | 0.69 | Moderate agreement |

| 3 | 0.80 | Substantial agreement |

| 4 | 0.73 | Substantial agreement |

| 5 | 0.76 | Substantial agreement |

| 6 | 0.71 | Substantial agreement |

| 7 | 0.72 | Substantial agreement |

| 8 | 0.75 | Substantial agreement |

| 9 | 0.68 | Moderate agreement |

| 10 | 0.77 | Substantial agreement |

| 11 | 0.70 | Substantial agreement |

| 12 | 0.74 | Substantial agreement |

| Characteristics of the Study Participants | |

|---|---|

| Gender (N) % | |

| Male | (65) 74% |

| Female | (23) 26% |

| Age, years (N) % | |

| 22–34 | (41) 47% |

| 35–45 | (29) 33% |

| 46–60 | (14) 16% |

| Over 60 | (4) 4% |

| Education Level (N) % | |

| Diploma | (6) 7% |

| Bachelor’s degree | (54) 61% |

| Bachelor’s degree and Postgraduate Certificate in Critical Care | (16) 18% |

| Bachelor’s degree and other postgraduate certificate qualification | (9) 10% |

| Master’s degree in science | (1) 1% |

| Master’s degree in science and Postgraduate Certificate in Critical Care | (1) 1% |

| Not declared | (1) 1% |

| Years of experience (mean ± SD) | 14.14 ± 9.07 |

| Years of experience in ICU (mean ± SD) | 10.7 ± 8.83 |

| Characteristics of the Study Participants | |

|---|---|

| Gender (N) % | |

| Male | (7) 70% |

| Female | (3) 30% |

| Age, years (N) % | |

| 22–34 | (5) 50% |

| 35–45 | (4) 40% |

| 46–60 | (1) 10% |

| Education Level (N) % | |

| Bachelor’s degree and Postgraduate Certificate in Critical Care | (5) 50% |

| Master’s degree in science and Postgraduate Certificate in Critical Care | (5) 50% |

| Years of experience (mean ± SD) | 9.9 ± 7.1 |

| Years of experience in ICU (mean ± SD) | 8 ± 6.6 |

| Item | Relevance | Clarity | Simplicity | Ambiguity | I-CVI | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Age | 0 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0.8 |

| Weight/Tissue Viability | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| PMH/Affecting Condition | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| General Skin Condition | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| Mental State | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Mobility | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 1 |

| Haemodynamics | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 1 |

| Respiration | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 0.9 |

| Oxygen Requirements | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 0.9 |

| Nutrition | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 0.9 |

| Incontinence | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 0.9 |

| Hygiene | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0.9 |

| Deduct 1 point → time spent in surgery/scan in last 48 h | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 1 |

| Deduct 1 point → if requires blood products | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 1 |

| Deduct 1 point → for hypothermia until warm | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rollo, C.; Magnani, D.; Alberti, S.; Fazzini, B.; Rovesti, S.; Ferri, P. Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Content Validity of a Modified Italian Version of the Jackson/Cubbin Pressure Injury Risk Assessment Scale for ICU Patients. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070256

Rollo C, Magnani D, Alberti S, Fazzini B, Rovesti S, Ferri P. Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Content Validity of a Modified Italian Version of the Jackson/Cubbin Pressure Injury Risk Assessment Scale for ICU Patients. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(7):256. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070256

Chicago/Turabian StyleRollo, Chiara, Daniela Magnani, Sara Alberti, Brigitta Fazzini, Sergio Rovesti, and Paola Ferri. 2025. "Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Content Validity of a Modified Italian Version of the Jackson/Cubbin Pressure Injury Risk Assessment Scale for ICU Patients" Nursing Reports 15, no. 7: 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070256

APA StyleRollo, C., Magnani, D., Alberti, S., Fazzini, B., Rovesti, S., & Ferri, P. (2025). Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Content Validity of a Modified Italian Version of the Jackson/Cubbin Pressure Injury Risk Assessment Scale for ICU Patients. Nursing Reports, 15(7), 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070256