Implementing a Professional Development Programme (ProDeveloP) for Newly Graduated Nurses: A Study Protocol

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Transition from Nursing Student to Registered Nurse

1.2. Being New in the Profession

1.3. An Overview of Professional Development Programmes

1.4. Theoretical Frameworks for Becoming a Professional Nurse

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Settings and Samples

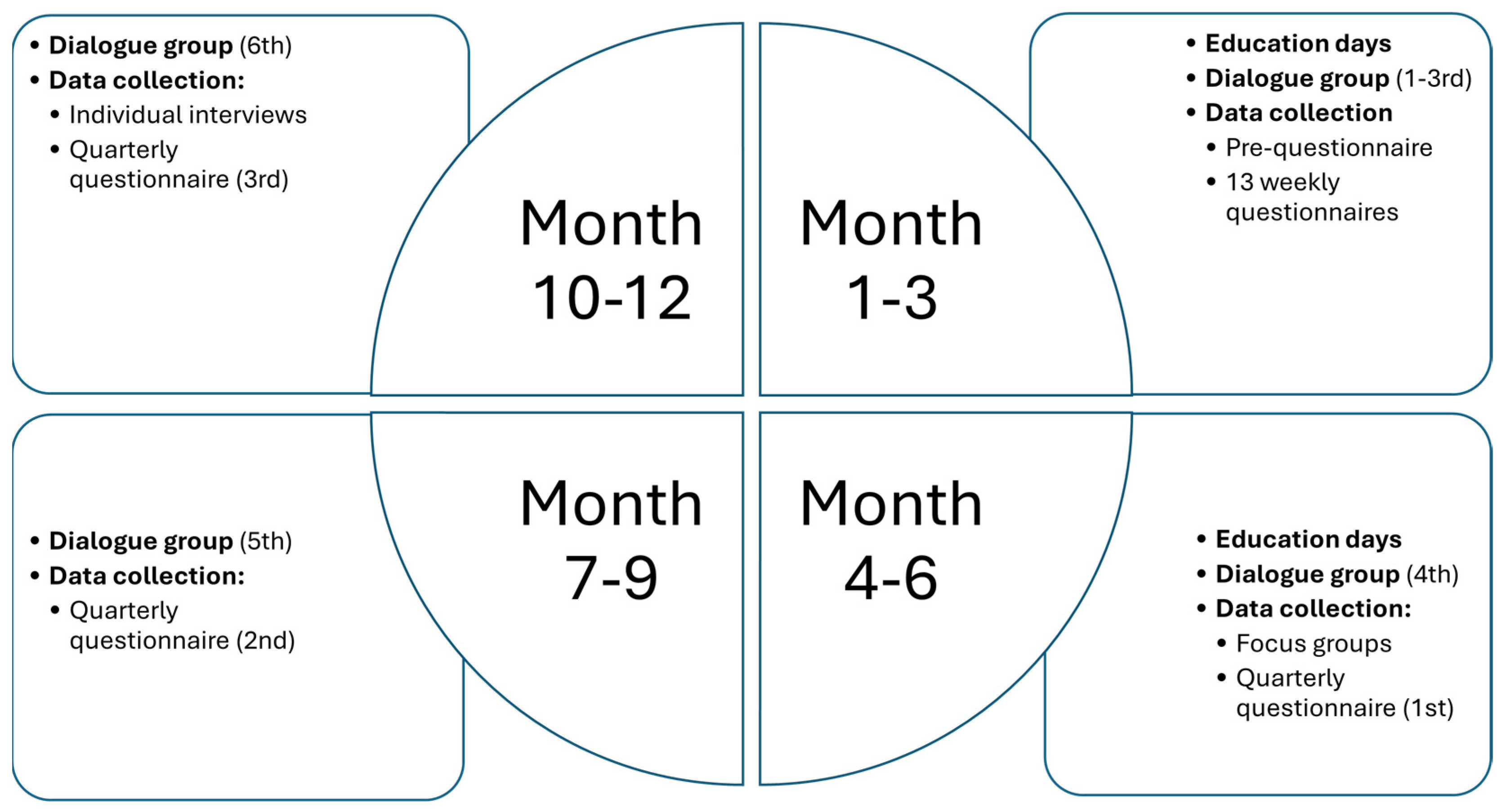

2.3. Data Collection

| Week 1 | Weeks 2–14 | Months 4–12 |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-questionnaire: Demographic and contextual factors [36]. Educational factors [38,39]. | Weekly questionnaires: Organisational socialisation tactics (OST) [34,40]. Agentic Engagement scale [41]. General Nordic Questionnaire for Psychological and Social Factors at Work (QPS Nordic) [42,43]. Needs Satisfaction and Frustration scale (NSFS) [44,45]. Belongingness and Uncertainty scale [46]. Copenhagen Psychosocial questionnaire (COPSOQ) [47]. Stress-Energy questionnaire (SEQ) [48,49,50,51]. Balancing Work with Recovery scale [52,53]. Emotional Demands Targeting scale [44,54]. Spare-time activities [36]. Leisure activities [36]. Karolinska Sleep questionnaire [55]. Workload scale [55]. | Quarterly questionnaires: Occupational Self-efficacy scale [56]. Job Satisfaction scale [57]. Organisational Commitment on Job Turnover Intention scale [58]. Self-rated General Health Status scale [59,60]. Scale of Work Engagement and Burnout (SWEDBO) [61]. Mood and Arousal scale of emotions, depression, and anxiety [62]. Recovery, stress, and sleep items from the weekly questionnaire (see Weeks 2–14) are also included. |

2.4. Analyses and Data Processing

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Development of the ProDeveloP

3.1. Implementation Strategy

3.2. Pedagogical Strategies

4. Dissemination

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NGN | Newly Graduated Nurse |

| ProDeveloP | Professional Development Programme |

| RN | Registered Nurse |

References

- Widarsson, M.; Asp, M.; Letterstål, A.; Södersved, M.L. Newly Graduated Swedish Nurses’ Inadequacy in Developing Professional Competence. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2020, 51, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchscher, J.E.B. Transition shock: The initial stage of role adaption for newly graduated Registered Nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 65, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gellerstedt, L.; Moquist, A.; Roos, A.; Bergkvist, K.; Craftman, Å.G. Newly graduated nurses’ experiences of a trainee programme regarding the introduction process and leadership in a hospital setting—A qualitative interview study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1685–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, P.; Agrenius, B.; Frögéli, E.; Rudman, A. New Professionals: Organizational Strategies to Support Vitality and Learning During Early Employment in Highly Emotionally Demanding Occupations [Nya Professionella: Organisatoriska Strategier för att Stödja Vitalitet och Lärande Under Första Anställningstiden i Yrken Med Höga Emotionella Krav]; Report C, 2020:11; Karolinska Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020; Available online: https://www.suntarbetsliv.se/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Rapport-Nya-professionella-2020.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Harrison, H.; Birks, M.; Franklin, R.C.; Mills, J. Fostering graduate nurse practice readiness in context. Collegian 2020, 27, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Södersved Källestedt, M.L.; Asp, M.; Letterstål, A.; Widarsson, M. Perceptions of managers regarding prerequisites for the development of professional competence of newly graduated nurses: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4784–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willman, A.; Nilsson, J.; Bjuresäter, K. Professional development among newly graduated registered nurses working in acute care hospital settings: A qualitative explorative study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 3304–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.S.W.; Che, W.S.W.; Cheng, M.T.C.; Cheung, C.K. Challenges of fresh nursing graduates during their transition period. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2018, 8, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, A.; Hunsberger, M.; Crea-Arsenio, M.; Akhtar-Danesh, N. Policy to practice: Investment in transitioning new graduate nurses to the workplace. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisholt, B.K.M. The professional socialization of recently graduated nurses—Experiences of an introduction program. Nurse Educ. Today 2012, 32, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frögéli, E.; Rudman, A.; Ljótsson, B.; Gustavsson, P. Preventing stress-related ill health among new registered nurses by supporting engagement in proactive behaviors—A randomized controlled trial. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2020, 17, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.M.; Meyer, K.; Riemann, L.A.; Carter, B.T.; Brant, J.M. Transition Into Practice: Outcomes of a Nurse Residency Program. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2023, 54, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, V.; Giles, M.; Lantry, G.; McMillan, M. New graduate nurses’ experiences in their first year of practice. Nurse Educ. Today 2014, 34, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandler, M. Why are new graduate nurses leaving the profession in their first year of practice and how does this impact on ED nurse staffing? A rapid review of current literature and recommended reading. Can. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2020, 41, 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törnqvist, C. Staff Turnover Among Newly Graduated Nurses: The First Four Years in the Region of Västmanland [Personalomsättning Hos Nyutexaminerade Sjuksköterskor: De Första Fyra Åren i Region Västmanland]; The Region of Västmanland: Västerås, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ulupinar, S.; Aydogan, Y. New graduate nurses’ satisfaction, adaption and intention to leave in their first year: A descriptive study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1830–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomberg, K.; Isaksson, A.K.; Allvin, R.; Bisholt, B.; Ewertsson, M.; Kullén Engström, A.; Ohlsson, U.; Johansson, A.S.; Gustafsson, M. Work stress among newly graduated nurses in relation to workplace and clinical group supervision. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, W.; Boxall, P.; Parsons, M.; Cheung, G. Factors predicting Registered Nurses’ intentions to leave their organization and profession: A job demands-resources framework. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 864–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, A.; Ramstrand, N.; Nyström, M.; Andersson Hagivara, M.; Palmér, L. Novice nurses’ perceptions of acute situations. A phenomenographic study. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2018, 40, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engström, M.; Mårtensson, G.; Pålsson, Y.; Strömberg, A. What relationships can be found between nurses’ working life and turnover? A mixed-methods approach. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 30, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frögéli, E.; Rudman, A.; Gustavsson, P. The relationship between task mastery, role clarity, social acceptance, and stress: An intensive longitudinal study with a sample of newly registered nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 91, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, A.; Frögéli, E.; Skyvell Nilsson, M. Gaining acceptance, insight and ability to act: A process evaluation of a preventive stress intervention as part of a transition-to-practice programme for newly graduated nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 80, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakon, S.; Craft, J.; Wirihana, L.; Christensen, M.; Barr, J.; Tsai, L. An integrative review of graduate transition programmes: Developmental considerations for nursing management. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2018, 28, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, A.; Berglund, M.; Kjellsdotter, A. Clinical Nursing Introduction Program for new graduate nurses in Sweden: Study protocol for a prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rush, K.L.; Janke, R.; Duchscher, J.E.; Phillips, R.; Kaur, S. Best practices of formal new graduate transition programs: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 94, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berglund, M.; Kjellsdotter, A.; Wills, J.; Johansson, A. The best of both worlds—Entering the nursing profession with support of a transition programme. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2022, 36, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, A.; Billett, S.; Skyvell Nilsson, M. A bridge over troubled water?—Exploring learning processes in a transition program with newly graduated nurses. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 51, 102982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.; Hawker, C.; Carrier, J.; Rees, C. A systematic review of the effectiveness of strategies and interventions to improve the transition from student to newly qualified nurse. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 1254–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, P. Using the Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition to Describe and Interpret Skill Acquisition and Clinical Judgment in Nursing Practice and Education. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2004, 24, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchscher, J.E.B.; Corneau, K. Nursing the Future—Building New Graduate Capacity (Part I). Nurs. Adm. Q. 2023, 47, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchscher, J.E.B. Out in the Real World: Newly Graduated Nurses in Acute-care Speak Out. J. Nurs. Adm. 2001, 31, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N.; Laurenceau, J.-P. Intensive Longitudinal Methods: An Introduction to Diary and Experience Sampling Research; The Guilford Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Artologik. Survey & Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.artologik.com/se/survey-report (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Bauer, T.N.; Bodner, T.; Erdogan, B.; Truxillo, D.M.; Tucker, J.S. Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M.; Uggerslev, K.L.; Fassina, N.E. Socialization tactics and newcomer adjustment: A meta-analytic review and test of a model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 70, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frögéli, E.; Högman, N.; Aurell, J.; Rudman, A.; Dahlgren, A.; Gustavsson, P. An Intensive Prospective Study of Newly Registered Nurses’ Experiences of Entering the Profession During the Spring of 2016; Report B, 2017:4; Karolinska Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Frögéli, E.; Annell, S.; Rudman, A.; Inzunza, M.; Gustavsson, P. The Importance of Effective Organizational Socialization for Preventing Stress, Strain, and Early Career Burnout: An Intensive Longitudinal Study of New Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsson, G.; Gillström, P. The Student Mirror 2007 [Studentspegeln 2007]; Högskoleverkets Rapportserie, 2007:20; Högskoleverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kuh, G.D. The National Survey of Student Engagement: Conceptual Framework and Overview of Psychometric Properties. Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. 2001. Available online: https://centerofinquiry.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/conceptual_framework_2003.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Hedberg, J.; von Rüdiger, N.; Agrenius, B.; Rudman, A.; Gustavsson, P. Organizational Efforts to Introduce and Support New Employees. Occurrence and Effects on New Employees’ Uncertainty and Stress [Organisatoriska Insatser för att Introducera och Stödja Nya Medarbetare. Förekomst och Effekter på Nyanställdas Osäkerhet och Stress]; Rapport nr B, 2018:3; Karolinska Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, J. How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: The concept of agentic engagement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallner, M.; Elo, A.-L.; Gamberale, F.; Hottinen, V.; Knardahl, S.; Lindström, K.; Skogstad, A.; Orhede, E. Validation of the General Nordic Questionnaire (QPSNordic) for Psychological and Social Factors at Work; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2000.

- Rudman, A.; Omne-Pontén, M.; Wallin, L.; Gustavsson, P.J. Monitoring the newly qualified nurses in Sweden: The Longitudinal Analysis of Nursing Education (LANE) study. Hum. Resour. Health 2010, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadzibajramovic, E.; Ahlborg, G.; Grimby-Ekman, A.; Lundgren-Nilsson, Å. Internal construct validity of the stress-energy questionnaire in a working population, a cohort study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurell, J.; Wilsson, L.; Bergström, A.; Ohlsson, J.; Martinsson, J.; Gustavsson, P. Test of the Swedish Version of the Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (NSFS). 2015. Available online: https://docplayer.se/39937081-Utprovning-av-den-svenska-versionen-av-the-need-satisfaction-and-frustration-scale-nsfs.html#google_vignette (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Longo, Y.; Gunz, A.; Curtis, G.J.; Farsides, T. Measuring Need Satisfaction and Frustration in Educational and Work Contexts: The Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (NSFS). J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G.M.; Cohen, G.L. A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, T.S.; Hannerz, H.; Høgh, A.; Borg, V. The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire-a tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2005, 31, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, A.; Tucker, P.; Bujacz, A.; Frögéli, E.; Rudman, A.; Gustavsson, P. Intensive longitudinal study of newly graduated nurses’ quick returns and self-rated stress. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2021, 47, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellberg, A.; Iwanowski, S. The Stress/Energy Form: Development of a Method for Estimating Mood at Work [Stress/Energi-Formuläret: Utveckling av en Metod för Skattning av Sinnesstämning i Arbetet]; Arbetsmiljöinstitutet: Solna, Sweden, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kjellberg, A.; Wadman, C. Subjective Stress and Its Relationship with Psychosocial Conditions and Complaints—An Examination of the Stress-Energy Model [Subjektiv Stress och Dess Samband med Psykosociala Förhållanden och Besvär—En Prövning av Stress-Energi-Modellen]; Arbete och Hälsa, 2002:12; Arbetslivsinstitutet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson, M.; Vingård, E. Work Enthusiasm and Health: A Report from the HAKuL Project [Arbetslust och Hälsa. En Rapport från HAKuL-Projektet]; Karolinska Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- von Thiele Schwarz, U. Health and Ill Health in Working Women—Balancing Work and Recovery. Ph.D. Thesis, Stockholm University, Department of Psychology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sundin, L.; Hochwälder, J.; Bildt, C. A scale for measuring specific job demands within the health care sector: Development and psychometric assessment. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, M.; Åkerstedt, T.; Nordin, S. Psychometric evaluation and normative data for the Karolinska Sleep Questionnaire. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2013, 11, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, T.; Schyns, B.; Mohr, G. A short version of the occupational self-efficacy scale: Structural and construct validity across five countries. J. Career Assess. 2008, 16, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brayfield, A.H.; Rothe, H.F. An index of job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 1951, 35, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, A.; Sverke, M. The interactive effect of job involvement and organizational commitment on job turnover revisited: A note on the mediating role of turnover intention. Scand. J. Psychol. 2000, 41, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailis, D.S.; Segall, A.; Chipperfield, J.G. Two views of self-rated general health status. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, D.; Lindfors, P.; Gustavsson, P. Trends in self-rated health among nurses: A 4-year longitudinal study on the transition from nursing education to working life. J. Prof. Nurs. 2010, 26, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultell, D.; Gustavsson, J.P. A psychometric evaluation of the Scale of Work Engagement and Burnout (SWEBO). Work 2010, 37, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, R.E. The Biopsychology of Mood and Arousal; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation 679/2016. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr.html (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Richards, D.A. The complex interventions framework. In Complex Interventions in Health: An Overview of Research Methods; Richards, D.A., Hallberg, I.R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Letterstål, A.; Södersved Källestedt, M.L.; Widarsson, M.; Asp, M. Nursing Faculties’ Perceptions of Integrating Theory and Practice to Develop Professional Competence. J. Nurs. Educ. 2022, 61, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.; Audrey, S.; Barker, M.; Bond, L.; Bonell, C.; Hardeman, W.; Moore, L.; O’Cathain, A.; Tinati, T.; Wight, D.; et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: A summary of Medical Research Council guidance. In Complex Interventions in Health: An Overview of Research Methods; Richards, D.A., Hallberg, I.R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 222–231. [Google Scholar]

- Waltz, T.J.; Powell, B.J.; Matthieu, M.M.; Damschroder, L.J.; Chinman, M.J.; Smith, J.L.; Proctor, E.K.; Kirchner, J.E. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, C.E.; Harrison, M.B.; Godfrey, C.; Nincic, V.; Khan, P.A.; Oakley, P.; Ross-White, A.; Grantmyre, H.; Graham, I.D. Use and effects of implementation strategies for practice guidelines in nursing: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2021, 6, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogherty, E.J.; Estabrooks, C.A. Why do barriers and facilitators matter? In Complex Interventions in Health: An Overview of Research Methods; Richards, D.A., Hallberg, I.R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Skolarus, T.A.; Sales, A.E. Implementation issues: Towards a systematic and stepwise approach. In Complex Interventions in Health: An Overview of Research Methods; Richards, D.A., Hallberg, I.R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, E.K.; Powell, B.J.; McMillen, J.C. Implementation strategies: Recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldh, A.C.; Hälleberg-Nyman, M.; Joelsson-Alm, E.; Wallin, L. Facilitating facilitators to facilitate-Some general comments on a strategy for knowledge implementation in health services. Front. Health Serv. 2023, 3, 1112936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Saks, A.M.; Gruman, J.A. Getting newcomers on board. A review of socialization practices and introduction to socialization resources theory. In The Oxford Handbook of Organization Socialization; Wanberg, C., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, D.; Arnetz, B.; Wahlström, R.; Sandahl, C. Effects of dialogue groups on physicians’ work environment. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2007, 21, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, D.; Stotzer, E.; Wahlström, R.; Sandahl, C. Learning from dialogue groups—physicians’ perceptions of role. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2009, 23, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lornudd, C.; Bergman, D.; Sandahl, C.; von Thiele Schwarz, U. A randomised study of leadership interventions for healthcare managers. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2016, 29, 358–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Höglander, J.; Lindblom, M.; Södersved Källestedt, M.-L.; Letterstål, A.; Asp, M.; Widarsson, M. Implementing a Professional Development Programme (ProDeveloP) for Newly Graduated Nurses: A Study Protocol. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070243

Höglander J, Lindblom M, Södersved Källestedt M-L, Letterstål A, Asp M, Widarsson M. Implementing a Professional Development Programme (ProDeveloP) for Newly Graduated Nurses: A Study Protocol. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(7):243. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070243

Chicago/Turabian StyleHöglander, Jessica, Magdalena Lindblom, Marie-Louise Södersved Källestedt, Anna Letterstål, Margareta Asp, and Margareta Widarsson. 2025. "Implementing a Professional Development Programme (ProDeveloP) for Newly Graduated Nurses: A Study Protocol" Nursing Reports 15, no. 7: 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070243

APA StyleHöglander, J., Lindblom, M., Södersved Källestedt, M.-L., Letterstål, A., Asp, M., & Widarsson, M. (2025). Implementing a Professional Development Programme (ProDeveloP) for Newly Graduated Nurses: A Study Protocol. Nursing Reports, 15(7), 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070243