Spanish Nurses’ Knowledge and Perceptions of Climate Change: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

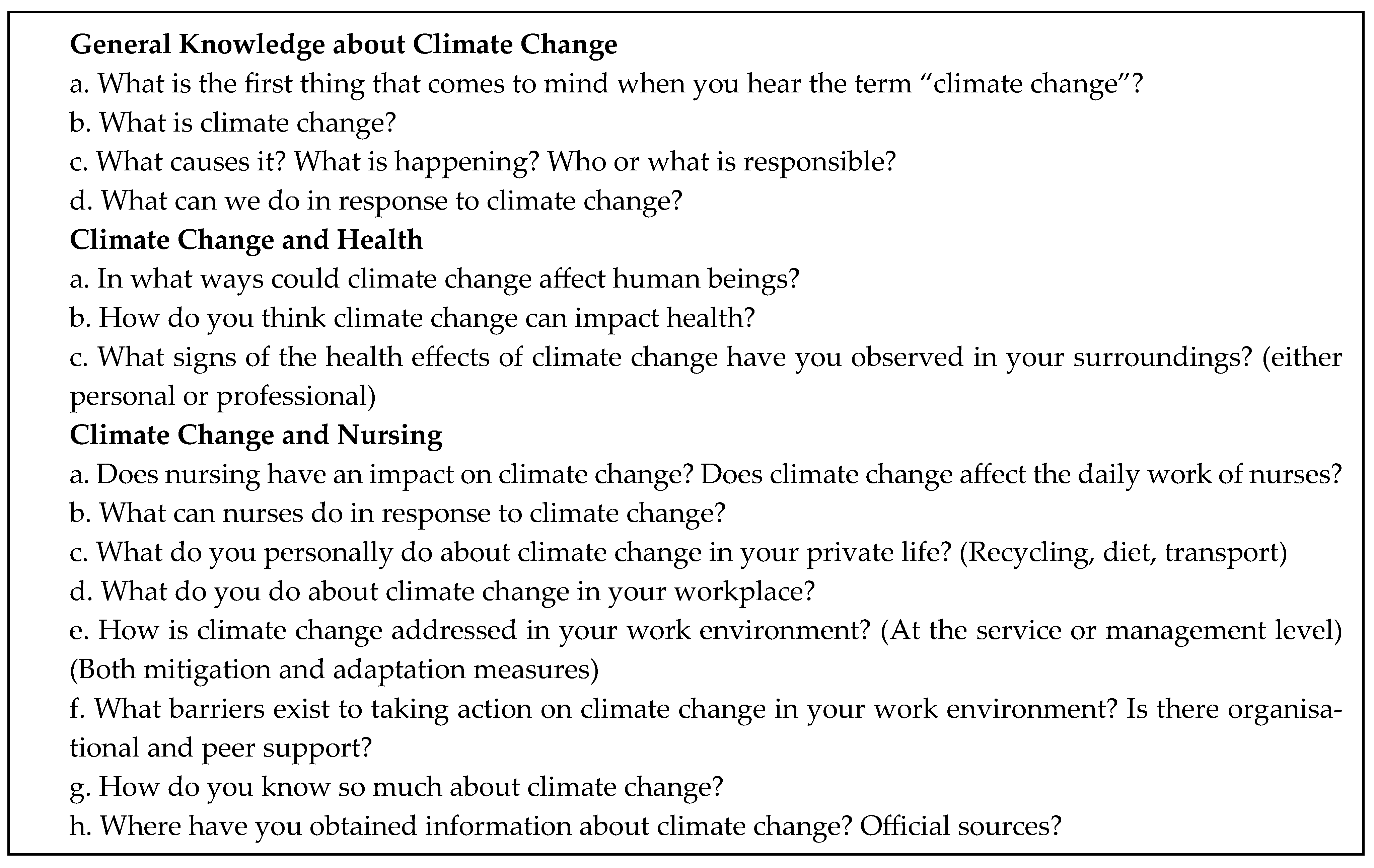

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Participants and Setting

2.2. Data Collection

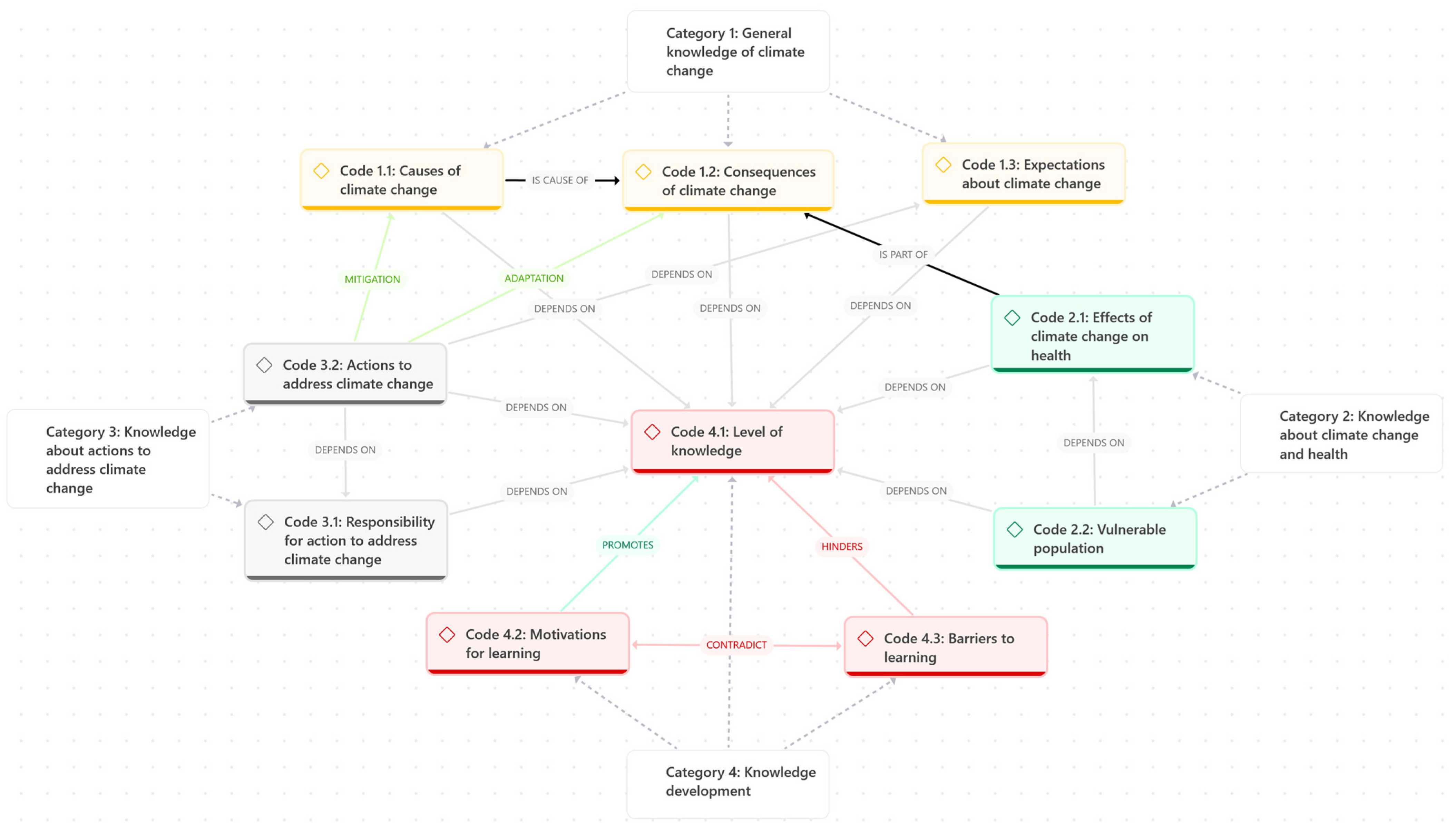

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Quality and Rigour

3. Results

3.1. Category 1: General Knowledge of Climate Change

3.1.1. Code 1.1: Causes of Climate Change

“I think it’s a bit of everything. As human beings, we sort of assume the Earth belongs to us, and we do all sorts of outrageous things… with oil, with energy, with the sun, with electricity and all that. But also, I believe there’s a natural component from the planet itself.”(N21)

“Maybe it is a natural cycle, but mankind’s hand is speeding it up a little—with so many factories, all the planes, the transport, and all those things that, really, didn’t exist before.”(N2)

“I mean, the air pollution—which we ourselves are creating—yes, it does cause this climate change because we’re damaging the ozone layer and ending up with less natural protection from the planet.”(N21)

“Well, my perception is that it’s like a layer […] that we’re creating in the atmosphere through consumption, […] like cars, fuel, for generating energy—we’re not using renewable energy, I mean, it’s all gas burning […].”(N12)

3.1.2. Code 1.2: Consequences of Climate Change

“That we reach much higher temperatures, that there’s no water in the rivers like we’re used to, […] and that, of course, affects the entire ecosystem, impacting other areas as well, you know? Microorganisms, animals, plants.”(N18)

“Well, pollution and, yeah, all these changes, many of which are already plain to see. The lack of rain, the extreme heat… These strange weather changes we’re having… And well, the melting of the polar ice caps.”(N16)

“It seems we’re experiencing periods of torrential rain, periods of drought… the global temperature has risen. […] It seems like we’re heading towards extreme climates. […] What we can say in Spain, […] is that the temperature is rising. […] And also, it’s very dry.”(N24)

3.1.3. Code 1.3: Expectations Regarding Climate Change

“We’ve been witnessing climate change for… for many years now. […] With phenomena that may be used to happen once every so often, and now we’re seeing them more and more. But it’s not something in the future. It’s something that’s happening now and that, with time, will get worse. It will get worse.”(N9)

“My first impression is that it’s unstoppable. That it’s been unstoppable for years now and that it’s been like the boy who cried wolf, hasn’t it? Always saying it’s coming, it’s coming—but people didn’t believe it, and now there’s no turning back.”(N19)

“I’m pessimistic about this in the long run. Will I selfishly not be around? Yes. And I hope so. Because otherwise, it would be unbearable.”(N9)

3.2. Category 2: Knowledge Regarding Climate Change and Health

3.2.1. Code 2.1: Health Effects of Climate Change

“Lung diseases come first. […] Increases in cases that weren’t diagnosed before… Many types of cancer, […]. And anxiety… depressions… […] I imagine it’s due to air pollution, […] and then the temperature changes. […] Even climate change in the ‘calima’ [airborne dust] that comes from North Africa.”(N5)

“Temperature, drought, a change in how all these conditions affect people’s health. Heat strokes in older people, decompensations in people with heart failure. They decompensate far more in the summer months, far more. And mental health in general, especially among young people, right? This anxiety about the harsh conditions and not having any kind of future project.”(N18)

“The fact that it’s raining less, […] farming becomes more difficult, […]. To give you an example, […] the olive harvest was awful this year, so the price of olive oil will go up, […] and I’ll end up cooking with palm oil, which is much worse for your health, or with margarine, or another kind. I’ll be replacing the healthier oil—or at least the one I consider healthier—with one that’s cheaper.”(N22)

“It’s just really hard to sleep when it’s over thirty degrees. […] So, just imagine the sleep cycle—all those patients who already sleep poorly, all those who need benzodiazepines or anything else to sleep. If you add such high temperatures to that, it’s the perfect breeding ground for someone to throw themselves out the window. […] It should even be considered whether it really has an impact on, for example, bipolar patients, depressive patients, patients with any type of disorder.”(N8)

3.2.2. Code 2.2: Vulnerable Populations

“Because… any change affects people, but right now, in the case of an elderly person, a sudden rise in temperature brings about a whole range of changes—I mean, it affects all the systems in an older person’s body.”(N30)

“I don’t know… for example, older people or very young children—those who are more vulnerable—being exposed to high temperatures, well, that causes dehydration, doesn’t it? Just as an example.”(N27)

“It can also affect us, especially those who are more vulnerable, particularly elderly individuals, people who already have some chronic illness or who are immunosuppressed, cancer patients…”(N28)

3.3. Category 3: Knowledge Relating to Actions Against Climate Change

3.3.1. Code 3.1: Responsibility for Action on Climate Change

“I mean, there’s no real intention behind anything […] it’s absolute hypocrisy, isn’t it? I mean, stop holding more climate change summits—you all meet up for four days, eat like pigs, everyone flies in by plane, and then you don’t reach any agreement, you know? Honestly, there’s nothing more hypocritical than climate change conventions—completely. […] And it’s not even because they’re not going to do anything—I’m not going to do anything either, you know? […] So you focus on what’s close to you and the group of humans you belong to—my family, my workplace, the population I care for… well, let’s see what we can do here, right?”(N18)

“The problem is that I can do my little bit, and everyone can do a little bit, but the issue is with the major powers or the people who actually have the ability to take action. I mean, these climate summits—how many years have they been going on? And what agreements have they reached? ‘No, we’ll postpone it to 2020.’ ‘No, let’s push it to 2035.’ Oh come on, for fuck’s sake! Postpone it to 2050 and by then we won’t even have a climate left, we won’t have anything. Sure, you as an individual can do small things, but if nothing is done on a large or macroeconomic scale, it doesn’t matter how much you do individually… does it?”(N25)

“On an individual level, I can do my bit, but that’s all it is—a grain of sand. So it needs to be large groups who are clear about this and truly convinced that we are influencing climate change. Until that happens, well, it’s difficult.”(N24)

3.3.2. Code 3.2: Actions Against Climate Change

“I mean, waste management. Erm… well, electricity—I’m quite obsessive about lights being on when they’re not needed. Then water—responsible water use. […] Also… I don’t know, when it comes to consumption, I’m increasingly aware—or at least I try to be more aware—of responsible consumption. Right? Plastics… […]. Eating seasonal fruit, local fruit, […].”(N6)

“I recycle, I try to reduce energy use, try to cut down on petrol consumption, electricity, water. I try to do those little things—and to teach them to my daughter.”(N21)

“So, you try to cut down on consumption—also for one reason, because all these energy sources are so expensive that we’ve been forced to cut back, but because of our wallets. Not so much because we’re convinced of how harmful they are, but because it’s hitting our finances.”(N24)

“I don’t behave any differently at work than I do at home. Just like I have the habit of recycling at home, I recycle lids at work, I recycle the little glass jars, I recycle the plastic, I recycle the paper.”(N20)

3.4. Category 4: Development of Knowledge

3.4.1. Code 4.1: Level of Knowledge

“What little I know comes from the news, what you see […]. My partner is often more interested in the topic and talks to me about it. […] Honestly, I haven’t picked up an article or a book to read about climate change—so it’s really just from news and the odd conversation that comes up.”(N28)

“I mostly do, well, maybe it’s more of an indirect search. I look up a lot of stuff about food and nutrition. […] So, as the phone and computer always show you related things, I end up getting news alerts and they catch my interest, and I click on them. No, it’s not like I actively search for it directly every day.”(N5)

“It’s something you come to notice through evidence—things you hear, things you read, things you see on the internet and in the news—and then you start to realise in your daily life, you think, oh right, it’s true.”(N31)

3.4.2. Code 4.2: Motivations for Learning

“I would love to receive a session on climate change from the perspective we’re talking about here […] I mean, as a nurse and in the environment I work in, it wouldn’t have occurred to me—but yes, of course, yes.”(N7)

“But the thing is, there will still be people after me. I mean, for example, I’m not a mother, but other people will still be here.”(N9)

“And I think a lot about what we’re going to leave for our children, and I believe that… […] maybe not my children, but I’m not sure in what conditions my grandchildren will live.”(N5)

“Concern, information… mainly about things that affect health. If this affects me, why does it affect me, and what do I need to avoid so that it doesn’t?”(N20)

3.4.3. Code 4.3: Barriers to Learning

“In general, my feeling is one of fear, uncertainty, and mistrust—not knowing what’s going to happen.”(N15)

“Honestly, it makes me really sad and really angry. Truly an overwhelming sense of helplessness.”(N8)

“I don’t go into it too deeply. So I don’t get overwhelmed either.”(N9)

“I try to read about the topic. Not too much, because to be honest, I end up feeling really hopeless seeing that nothing is improving. And sometimes I’d almost rather live in ignorance. That’s it. It’s harsh, but it’s the reality. It’s really because… because I feel so powerless seeing that we’re not moving forward… I’d almost rather not know anything.”(N5)

“I studied nursing from 2014 to 2018—climate change already existed, it was already a current issue—and I don’t remember any subject where it was discussed. So, they could have instilled the topic a bit more from university onwards. […] I think the problem is ignorance, a lot of the time.”(N28)

“INTERVIEWER: What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you hear ‘climate change’?

INTERVIEWEE: The first thing, mm, maybe anxiety. […] Anxiety, because it’s something that feels uncontrollable, right? And… and well, also because of the news—the way they report what’s happening with climate change. […] It’s like a bombardment of news, right? And told in a somewhat catastrophising way. […] I often try, well, not… or to stay informed, but maybe in another way. A radio show or headlines, but without going too deep.”(N4)

4. Discussion

4.1. Nursing Potential and Areas in Need of Strengthening

4.2. The Influence of Demographic Data

4.3. The Significance of the Audience’s Context

4.4. Informal Knowledge Sources and Their Consequences

4.5. Eco-Anxiety

4.6. Leadership Gap

4.7. Individual Actions and Motivation

4.8. Limitations

4.9. Implications for Clinical Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Id | Sex | Age 1 | Speciality | Experience in the Speciality 1 | Pollution Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | Female | - | Urgency | 19 | Medium |

| N2 | Male | - | Respiratory medicine | 11 | Medium |

| N3 | Male | 33 | Cardiology | 6 | Medium |

| N4 | Female | 48 | Geriatrics | 4 | Medium |

| N5 | Female | 37 | Primary care | 14 | Medium |

| N6 | Female | 42 | Primary care | 4 | Low |

| N7 | Female | 51 | Geriatrics | 12 | Low |

| N8 | Male | 49 | Cardiology | 10 | High |

| N9 | Female | 43 | Respiratory medicine | 3 | Low |

| N10 | Female | 50 | Primary care | 29 | High |

| N11 | Male | 26 | Respiratory medicine | 4 | Medium |

| N12 | Female | 45 | Geriatrics | 13 | High |

| N13 | Female | 27 | Emergency services | 1 | Low |

| N14 | Female | 45 | Geriatrics | 20 | Low |

| N15 | Female | 36 | Geriatrics | 1 | Medium |

| N16 | Female | 31 | Primary care | 4 | High |

| N17 | Female | 39 | Emergency services | 4 | Low |

| N18 | Female | 54 | Primary care | 18 | High |

| N19 | Female | 54 | Cardiology | 30 | High |

| N20 | Female | 49 | Geriatrics | 25 | High |

| N21 | Female | 36 | Respiratory medicine | 2 | High |

| N22 | Male | 29 | Geriatrics | 4 | High |

| N23 | Female | 33 | Cardiology | 13 | Low |

| N24 | Male | 60 | Emergency services | 32 | Medium |

| N25 | Female | 44 | Respiratory medicine | 8 | Low |

| N26 | Female | 37 | Respiratory medicine | 12 | Low |

| N27 | Female | 29 | Cardiology | 3 | Low |

| N28 | Male | 31 | Emergency services | 5 | Low |

| N29 | Female | 37 | Cardiology | 17 | Medium |

| N30 | Female | 44 | Geriatrics | 10 | Medium |

| N31 | Female | 52 | Primary care | 27 | Medium |

References

- Forster, P.; Smith, C.; Walsh, T.; Lamb, W.; Lamboll, R.; Hall, B.; Hauser, M.; Ribes, A.; Rosen, D.; Gillett, N.; et al. Indicators of Global Climate Change 2023: Annual update of key indicators of the state of the climate system and human influence. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 2625–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization. State of the Climate 2024 Update for COP29. 2024. Available online: https://library.wmo.int/idurl/4/69075 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Romanello, M.; Walawender, M.; Hsu, S.C.; Moskeland, A.; Palmeiro-Silva, Y.; Scamman, D.; Ali, Z.; Ameli, N.; Angelova, D.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; et al. The 2024 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Facing record-breaking threats from delayed action. Lancet 2024, 404, 1847–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). European State of the Climate 2023; Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S): Reading, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- van Daalen, K.R.; Tonne, C.; Semenza, J.C.; Rocklöv, J.; Markandya, A.; Dasandi, N.; Jankin, S.; Achebak, H.; Ballester, J.; Bechara, H.; et al. The 2024 Europe report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Unprecedented warming demands unprecedented action. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e495–e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobías, A.; Dominic, R.; Iñigues, C. Mortalidad Atribuible por Calor en España [Mortality Attributable to Heat in Spain]. Fundación para la Investigación del Clima 2024. Available online: https://ficlima.shinyapps.io/mace/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Faranda, D.; Alvarez-Castro, M.C.; Ginesta, M.; Coppola, E.; Pons, F.M.E. Heavy Precipitations in October 2024 South-Eastern Spain DANA Mostly Strengthened by Human-Driven Climate Change. 2024. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/14052042 (accessed on 23 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Devastating Rainfall Hits Spain in Yet Another Flood-Related Disaster. Available online: https://wmo.int/media/news/devastating-rainfall-hits-spain-yet-another-flood-related-disaster (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Spain—Air Pollution Country Fact Sheet 2024. European Environment Agency’s Home Page. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/air-pollution/air-pollution-country-fact-sheets-2024/spain-air-pollution-country-fact-sheet-2024?activeTab=8a280073-bf94-4717-b3e2-1374b57ca99d (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Centro de Coordinación de Alertas Sanitarias y Emergencias. Riesgo de Detección de Nuevos Casos Autóctonos de Enfermedades Transmitidas por Aedes en España [Risk of Detection of New Autochthonous Cases of Aedes-Transmitted Diseases in Spain]. 2024. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/alertasEmergenciasSanitarias/alertasActuales/dengue/docs/20240619_ERR_EnfermTransmitidasAedes.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Centro de Coordinación de Alertas y Emergencias Sanitarias. Evaluación Rápida de Riesgo. Meningoencefalitis por Virus del Nilo Occidental en España. Resumen de la Temporada 2024 [Rapid Risk Assessment: West Nile Virus Meningoencephalitis in Spain—Summary of the 2024 Season]. 2025. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/alertasEmergenciasSanitarias/preparacionRespuesta/docs/20250131_ERR_Nilo_Occidental.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Costello, A.; Abbas, M.; Allen, A.; Ball, S.; Bell, S.; Bellamy, R.; Friel, S.; Groce, N.; Johnson, A.; Kett, M.; et al. Managing the health effects of climate change. Lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. Lancet 2009, 373, 1693–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P.; Blackstock, J.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Chaytor, S.; Colbourn, T.; Collins, M.; Cooper, A.; et al. Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1861–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. State of the World’s Nursing Report-2020; Geneva, 2020. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/331677/9789240003279-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Campbell, E.; Uppalapati, S.S.; Kotcher, J.; Thier, K.; Ansah, P.; Gour, N.; Maibach, E. Activating health professionals as climate change and health communicators and advocates: A review. Environ. Res. Health 2025, 3, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council of Nurses. Nurses, Climate Change and Health; Position Statement; International Council of Nurses: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kalogirou, M.R.; Olson, J.; Davidson, S. Nursing’s metaparadigm, climate change and planetary health. Nurs. Inq. 2020, 27, e12356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumake-Guillemot, J.; Villalobos-Prats, E.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Abrahams, J.; Bagayoko, M.; del Barrio, M.O.; Bakir, H.; Corvalan, C.; Hassan, N.; Kim, R.; et al. Operational framework for building climate resilient health systems. In Operational Framework for Building Climate Resilient Health Systems; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield, P.; Leffers, J.; Vásquez, M.D. Nursing’s pivotal role in global climate action. BMJ 2021, 373, n1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérubé, A.; Diallo, T.; Roberge, M.; Audate, P.P.; Leblanc, N.; Jobin, É.; Moubarak, N.; Guillaumie, L.; Dupéré, S.; Guichard, A.; et al. Practicing nurses’ and nursing students’ perceptions of climate change: A scoping review. Nurs. Open 2024, 11, e70043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akore Yeboah, E.; Adegboye, A.R.A.; Kneafsey, R. Nurses’ perceptions, attitudes, and perspectives in relation to climate change and sustainable healthcare practices: A systematic review. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2024, 16, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; Knight, V., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal, S.; Dhammi, S.; Guha, A. Climate crisis and language—A constructivist ecolinguistic approach. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 3581–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, G.; De Paula Baer, A.; Sestili, C.; Cocchiara, R.A.; Barbato, D.; Mannocci, A.; Del Cimmuto, A. Knowledge and perception about climate change among healthcare professionals and students: A cross-sectional study. South East. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guihenneuc, J.; Cambien, G.; Blanc-Petitjean, P.; Papin, E.; Bernard, N.; Jourdain, B.; Barcos, I.; Saez, C.; Dupuis, A.; Ayraud-Thevenot, S.; et al. Knowledge, behaviours, practices, and expectations regarding climate change and environmental sustainability among health workers in France: A multicentre, cross-sectional study. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e353–e364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ediz, Ç.; Uzun, S. The perspectives of nurses, as prominent advocates in sustainability, on the global climate crises and its impact on mental health. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Alcaraz, O.M.; Aparicio-Martínez, P.; Gomera, A.; Vaquero-Abellán, M. The environmental awareness of nurses as environmentally sustainable health care leaders: A mixed method analysis. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colorafi, K.J.; Evans, B. Qualitative Descriptive Methods in Health Science Research. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2016, 9, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, H.M.; Bamberg, M.; Creswell, J.W.; Frost, D.M.; Suárez-orozco, C. Journal Article Reporting Standards for Qualitative Primary, Qualitative Meta-Analytic, and Mixed Methods Research in Psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board Task Force Report. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2018, 73, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Knight, V., Ed.; Sage Handbook Of; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Olmos-Vega, F.M.; Stalmeijer, R.E.; Varpio, L.; Kahlke, R. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Med. Teach. 2023, 45, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraballo-Betancort, A.M.; Marcilla-Toribio, I.; Notario-Pacheco, B.; Moratalla-Cebrian, M.L.; Lucas-de la Cruz, L.; Martinez-Andres, M. Nurses’ Perceptions of Climate Change and its Effects on Health: A Qualitative Research Protocol. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231207575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, P.; Brinkmann, S.; Demetriou, C.; Roudometof, V.; Traianou, A.; Spencer, R.; Thorne, S.; Bryant, A.; McHugh, M.; Bhavnani, K.-K.; et al. The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, MS, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2008, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomini, M.K.; Cook, D.J.; Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: XXIII. Qualitative Research in Health Care A. Are the Results of the Study Valid? JAMA 2000, 284, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Environment Agency. Climate Change as a Threat to Health and Well-Being in Europe: Focus on Heat and Infectious Diseases; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022; ISBN 978-92-9480-508-9. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/climate-change-impacts-on-health (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- European Investment Bank. 81% of Spanish People in Favour of Stricter Government Measures Imposing Behavioural Changes to Address the Climate Emergency. Available online: https://www.eib.org/en/press/all/2021-360-81-percents-of-spanish-people-in-favour-of-stricter-government-measures-imposing-behavioural-changes-to-address-the-climate-emergency (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Ponte, N.; Alves, F.; Vidal, D.G. Exploring Portuguese physicians’ perceptions of climate change impacts on health: A qualitative study. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2024, 20, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, M.R.; Dahlke, S.; Davidson, S.; Yamamoto, S. Nurses’ perspectives on climate change, health and nursing practice. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4759–4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cugini, F.; Velez, E.V.; Gómez, P.R. The climate crisis and human health: Survey on the knowledge of nursing students in the Comunidad de Madrid. Nurse Educ. Today 2024, 132, 106041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotcher, J.; Maibach, E.; Miller, J.; Campbell, E.; Alqodmani, L.; Maiero, M.; Wyns, A. Views of health professionals on climate change and health: A multinational survey study. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e316–e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.; Tovar Jardon, S.; Fisher, S.; Blayney, M.; Ward, A.; Smith, H.; Struthoff, P.; Fillingham, Z. Peoples’ Climate Vote 2024. Results; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://peoplesclimate.vote/download (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Nicholas, P.K.; Breakey, S. Climate Change, Climate Justice, and Environmental Health: Implications for the Nursing Profession. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2017, 49, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.I.; Chai, H.Y.; Newell, B.R. Personal experience and the «psychological distance» of climate change: An integrative review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 44, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Survey of Japanese Nursing Professionals Regarding Climate Change and Health Survey Report; Tokyo, 2024. Available online: https://hgpi.org/en/research/ph-20240911.html (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- O’Neill, S.; Williams, H.T.P.; Kurz, T.; Wiersma, B.; Boykoff, M. Dominant frames in legacy and social media coverage of the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir, Y.; Walter, D.; Jamieson, P.E.; Jamieson, K.H. The Politicization of Climate Science: Media Consumption, Perceptions of Science and Scientists, and Support for Policy. J. Health Commun. 2024, 29 (Suppl. 1), 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopke, J. Tweeting on a Rapidly Warming Planet: Environmental Communication Social Media Research. Environ. Commun. 2023, 31, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, M.; Galeazzi, A.; Torricelli, M.; Di Marco, N.; Larosa, F.; Sas, M.; Mekacher, A.; Pearce, W.; Zollo, F.; Quattrociocchi, W.; et al. Growing polarization around climate change on social media. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rempel, H.; Kalogirou, M.R.; Dahlke, S.; Hunter, K.F. Understanding nurses’ experience of climate change and then climate action in Western Canada. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A.; Vaccari, C.; Kaiser, J. The Amplification of Exaggerated and False News on Social Media: The Roles of Platform Use, Motivations, Affect, and Ideology. Am. Behav. Sci. 2022, 69, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, H.; Huang, Y.; Han, R.; Fu, X.; Yuan, Z.; Liang, S. Negative news headlines are more attractive: Negativity bias in online news reading and sharing. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 30156–30169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.E.; Pröllochs, N.; Schwarzenegger, K.; Pärnamets, P.; Van Bavel, J.J.; Feuerriegel, S. Negativity drives online news consumption. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toff, B.; Nielsen, R.K. How News Feels: Anticipated Anxiety as a Factor in News Avoidance and a Barrier to Political Engagement. Polit. Commun. 2022, 39, 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzwiedz, C.; Katikireddi, S.V. Determinants of eco-anxiety: Cross-national study of 52,219 participants from 25 European countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33 (Suppl. 2), ckad160-069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecina, M.L.; Alonso-Ferres, M.; López-García, L.; Díaz-Silveira, C. Eco-Anxiety and Trust in Science in Spain: Two Paths to Connect Climate Change Perceptions and General Willingness for Environmental Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.I.; Morais Vilaça, I.; Henriques, A.; Matijasevich, A.; Pastor-Valero, M.; Barros, H. Eco-anxiety, its determinants and the adoption of pro-environmental behaviors: Preliminary findings from the Generation XXI cohort. Popul. Med. 2023, 5, A186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gideon Skinner. Ipsos Global Trustworthiness Index. 2024. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2024-11/ipsos-global-trustworthiness-index-2024.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Letter—Healthy Recovery. Available online: https://healthyrecovery.net/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Back, D.; Han, K.; Kim, J.; Baek, H. Climate change perceptions and behaviors among Korean nurses: The role of organizational initiatives. Nurs. Outlook 2025, 73, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Ali, S.; Xu, M. Recycling is not enough to make the world a greener place: Prospects for the circular economy. Green Carbon 2023, 1, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Li, X.; Jiang, Z.; Jiang, J. Recycle more, waste more? When recycling efforts increase resource consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anåker, A.; Nilsson, M.; Holmner, Å.; Elf, M. Nurses’ perceptions of climate and environmental issues: A qualitative study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 1883–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; Huang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Lui, Y.W.; Ye, F. Integrating climate change and sustainability in nursing education. Nurse Educ. Today 2024, 140, 106290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiitta, I.; Cubelo, F.; McDermott-Levy, R.; Jaakkola, J.J.K.; Kuosmanen, L. Climate change integration in nursing education: A scoping review. Nurse Educ. Today 2024, 139, 106210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Nieto, C.; López-Medina, I.M.; Linares-Abad, M.; Grande-Gascón, M.L.; Álvarez-García, C. Currículum enfermero y estrategias pedagógicas en materia de sostenibilidad medioambiental en los procesos de salud y cuidado [Nursing Curriculum and Pedagogical Strategies on Environmental Sustainability in Health and Care Processes]. Enfermería Glob. 2017, 16, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemery, J.; Balbus, J.; Sorensen, C.; Rublee, C.; Dresser, C.; Balsari, S.; Hynes, E.C. Training clinical and public health leaders in climate and health. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 2189–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swin, J.; Clayton, S.; Howard, G. Psychology and Global Climate Change: Addressing a Multi-faceted Phenomenon and Set of Challenges. Am. Psychol. Assoc. Wash. 2008, 66, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Frequency | (Percentage) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 24 | (77.42%) |

| Male | 7 | (22.58%) | |

| Age 1 | 20–29 | 4 | (12.90%) |

| 30–39 | 10 | (32.26%) | |

| 40–49 | 9 | (29.03%) | |

| 50–59 | 5 | (16.13%) | |

| 60–69 | 1 | (3.23%) | |

| Speciality | Geriatrics | 8 | (25.81%) |

| Primary care | 6 | (19.35%) | |

| Respiratory medicine | 6 | (19.35%) | |

| Cardiology | 6 | (19.35%) | |

| Emergency services | 5 | (16.13%) | |

| Experience in the speciality | <5 | 11 | (35.48%) |

| 5–15 | 11 | (35.48%) | |

| >15 | 9 | (29.03%) | |

| Pollution level | High | 9 | (29.03%) |

| Medium | 11 | (35.48%) | |

| Low | 11 | (35.48%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caraballo-Betancort, A.M.; Marcilla-Toribio, I.; Notario-Pacheco, B.; Moratalla-Cebrian, M.L.; Perez-Moreno, A.; del Hoyo-Herraiz, A.; Poyatos-Leon, R.; Martinez-Andres, M. Spanish Nurses’ Knowledge and Perceptions of Climate Change: A Qualitative Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070226

Caraballo-Betancort AM, Marcilla-Toribio I, Notario-Pacheco B, Moratalla-Cebrian ML, Perez-Moreno A, del Hoyo-Herraiz A, Poyatos-Leon R, Martinez-Andres M. Spanish Nurses’ Knowledge and Perceptions of Climate Change: A Qualitative Study. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(7):226. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070226

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaraballo-Betancort, Antonio Miguel, Irene Marcilla-Toribio, Blanca Notario-Pacheco, Maria Leopolda Moratalla-Cebrian, Ana Perez-Moreno, Alba del Hoyo-Herraiz, Raquel Poyatos-Leon, and Maria Martinez-Andres. 2025. "Spanish Nurses’ Knowledge and Perceptions of Climate Change: A Qualitative Study" Nursing Reports 15, no. 7: 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070226

APA StyleCaraballo-Betancort, A. M., Marcilla-Toribio, I., Notario-Pacheco, B., Moratalla-Cebrian, M. L., Perez-Moreno, A., del Hoyo-Herraiz, A., Poyatos-Leon, R., & Martinez-Andres, M. (2025). Spanish Nurses’ Knowledge and Perceptions of Climate Change: A Qualitative Study. Nursing Reports, 15(7), 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070226