Decoding Readiness for Clinical Practicum: Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Perspectives, Clinical Evaluations, and Comparative Curriculum Variations

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What explanations do the nursing students offer regarding their readiness for their clinical practicum?

- How do variations in clinical nursing study plans across diverse contexts explain nursing students’ readiness for their clinical practicum?

- What evidence of students’ readiness can be extracted from their clinical evaluations?

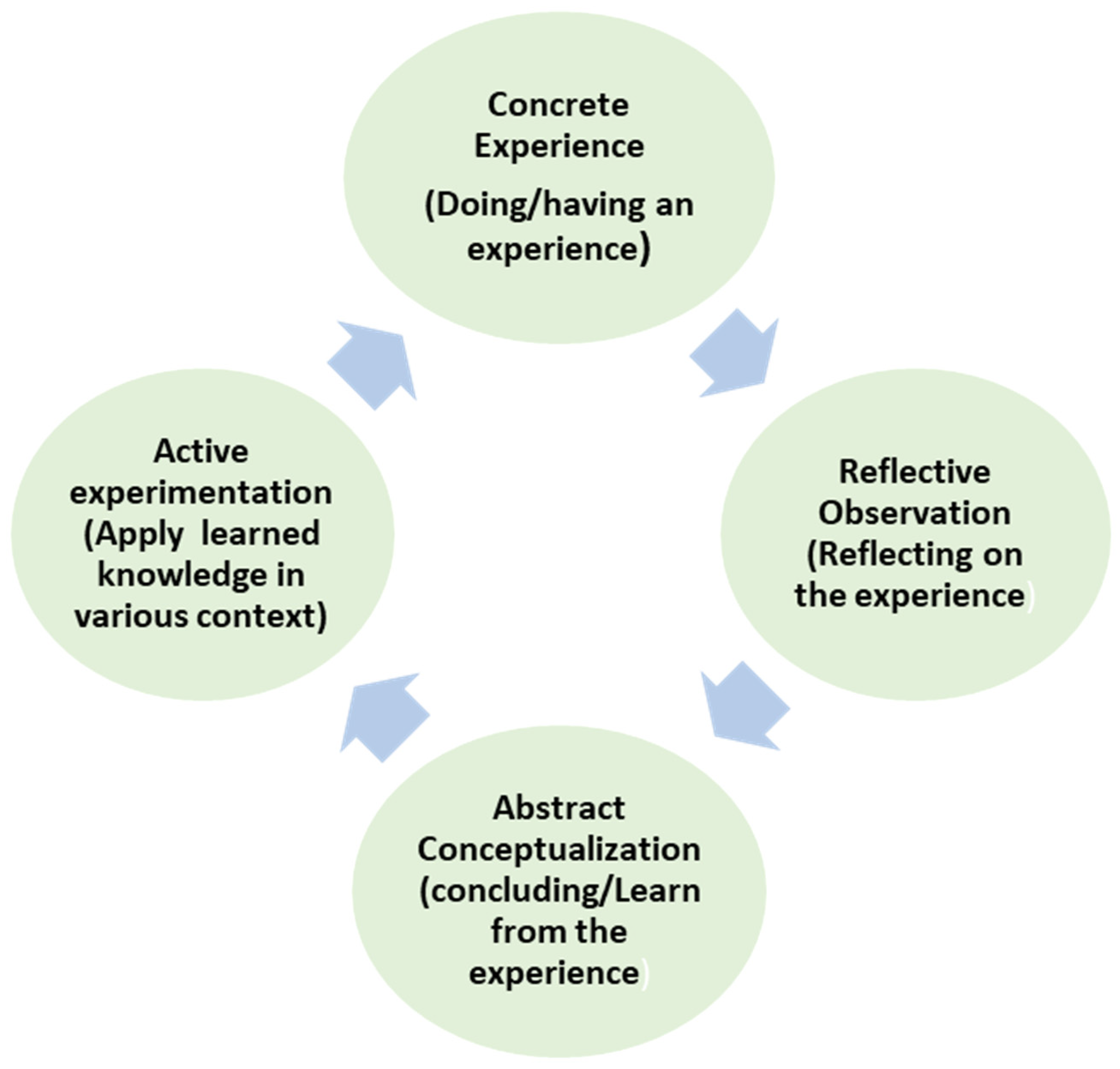

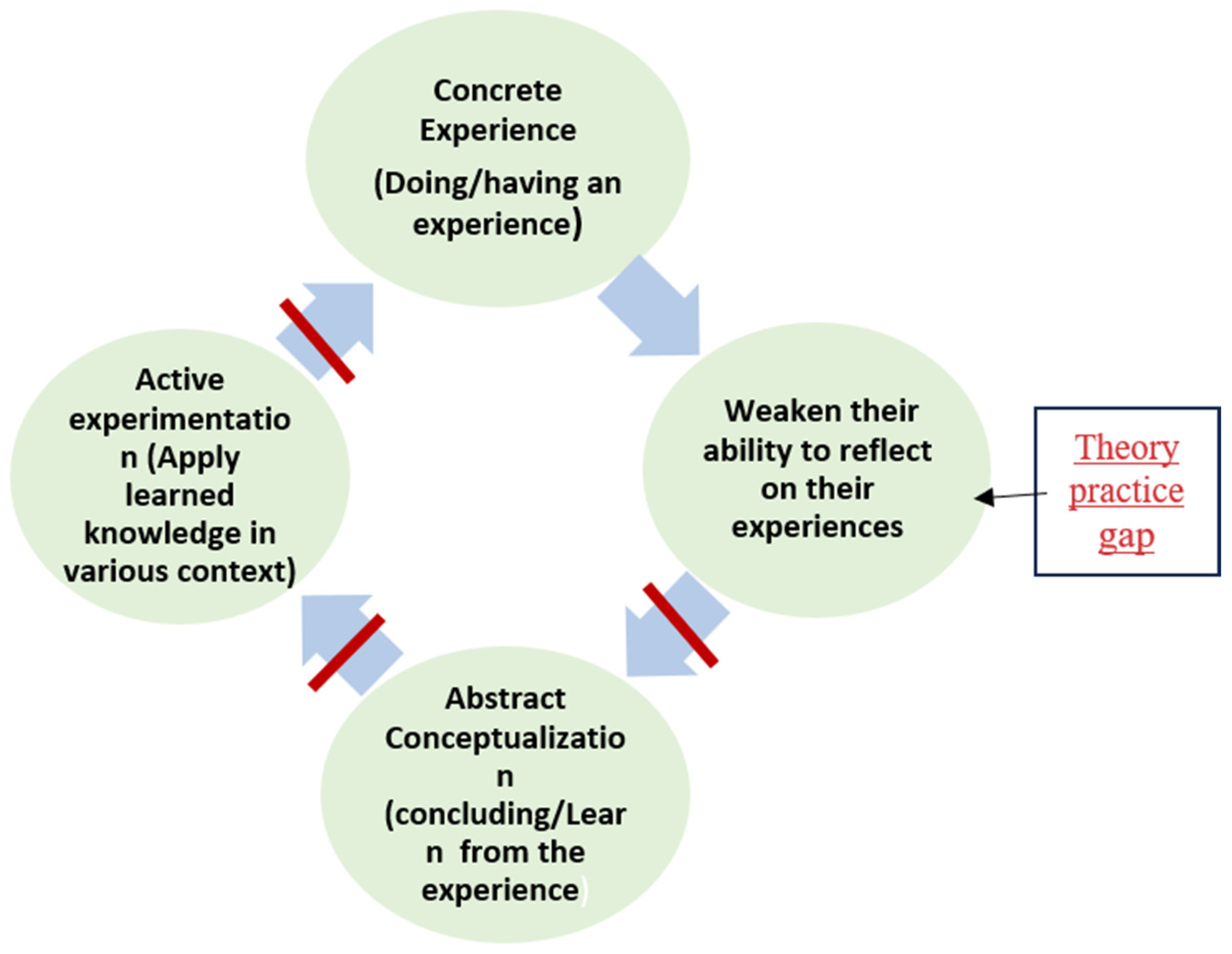

Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Approach

2.2. Instruments

- -

- What is your opinion on how effective was your preparation for clinical practice by theoretical and lab courses?

- What is your opinion about your readiness for clinical practice?

- How do you prepare yourself for clinical practice?

- What is your opinion on the effectiveness of lab sessions in preparing you for clinical practice, the lab session coverage of competencies that you need during the clinical placement, the opportunities you had in the lab to demonstrate procedures, and integrating lab sessions with theoretical nursing courses? Please rationalize your answer.

2.3. Study Population and Sampling Techniques

2.4. Reliability and Validity of Semi-Structured Interviews

2.5. Data Collection and Procedure

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Semi-Structured Interviews

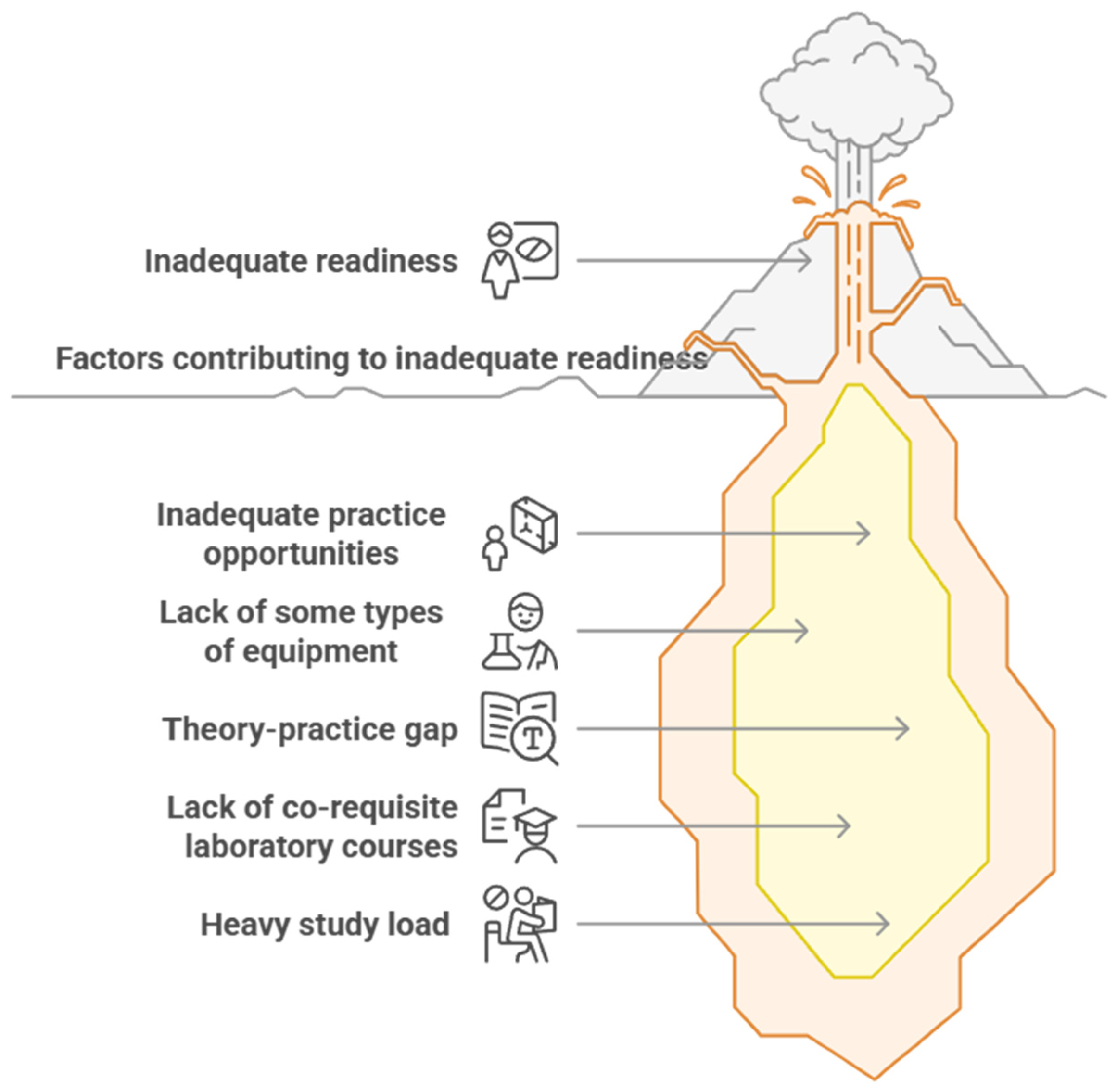

3.1.1. Incomplete Readiness for Clinical Practicum

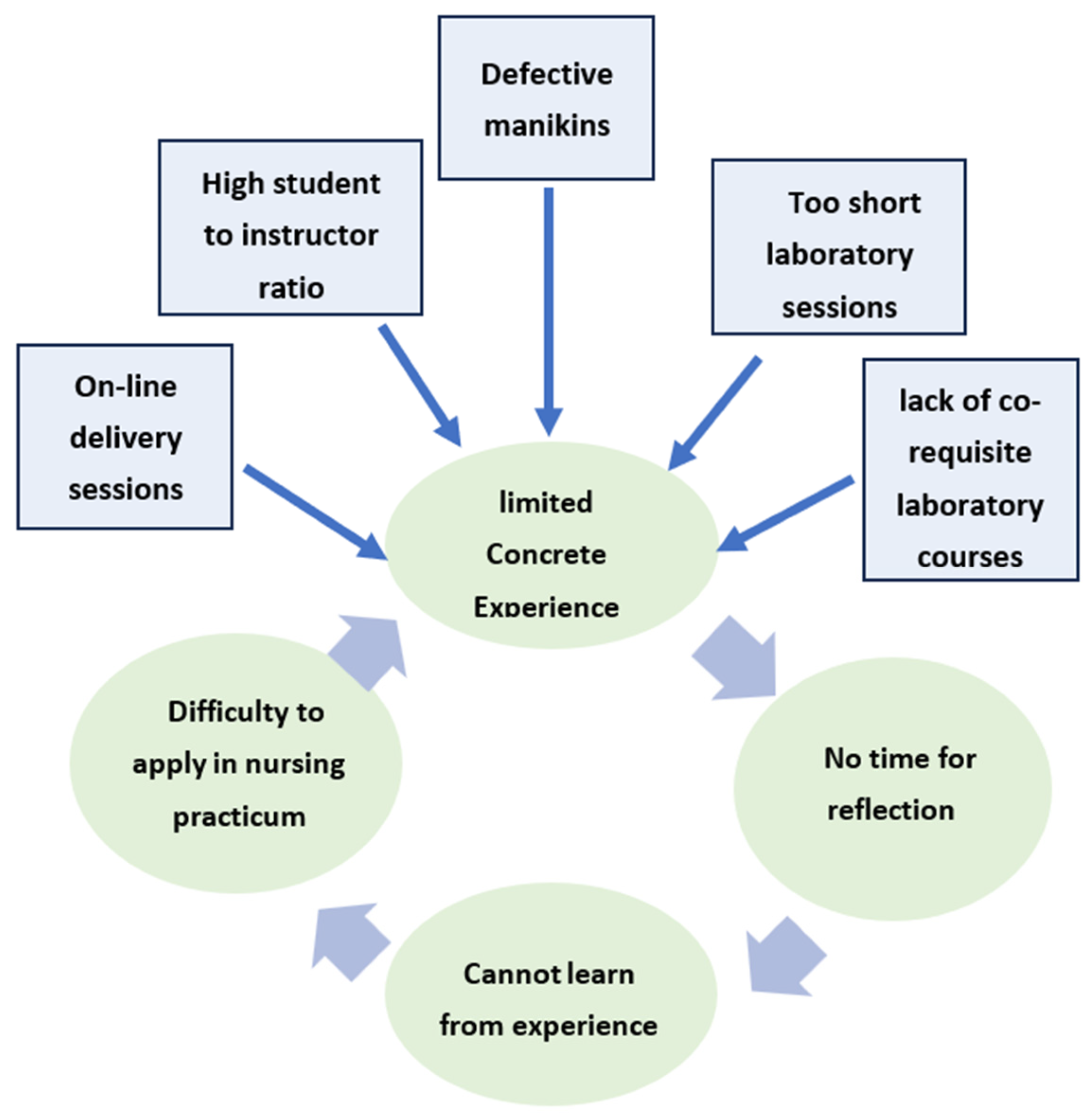

3.1.2. Factors Contributing to Incomplete Readiness

- Inadequate Practice Opportunities

- Lack of some types of equipment

- Theory and practice gap

- Lack of co-requisite laboratory courses

- Heavy study load or inadequate preparation for clinical day

3.2. Results of Document Analysis

3.2.1. First Document Analysis

3.2.2. Second Document Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of the Semi-Structured Interviews

4.2. Discussion of Document Analysis

4.3. Strengths

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Recommendations for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iwasiw, C.L.; Adrusyszyn, M.-A.; Goldenberg, D. Curriculum Development in Nursing Education; Jones & Bartlett Publishers: Ontario, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oermann, M.H.; De Gagne, J.C.; Phillips, B.C. Teaching in Nursing and Role of the Educator: The Complete Guide to Best Practice in Teaching, Evaluation, and Curriculum Development, 3rd ed.; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Craft-Blacksheare, M.; Frencher, Y. Using high fidelity simulation to increase nursing students’ clinical postpartum and newborn assessment proficiency: A mixed-methods research study. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 71, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewertsson, M.; Allvin, R.; Holmstrom, I.; Blomberg, K. Walking the bridge: Nursing students’ learning in clinical skill. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2015, 15, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Øgård-Repål, A.; De Presno, Å.K.; Fossum, M. Simulation with standardized patients to prepare undergraduate nursing students for mental health clinical practice: An integrative literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 66, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, T.I.; Onshuus, K.; Frisnes, H.; Gonzalez, M. Nursing students’ experiences in a marginal Norwegian nursing home learning environment. Int. Pract. Dev. J. 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Standards for the Initial Education of Professional Nurses and Midwives (No. WHO/HRH/HPN/08.6); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44100/1/WHO_HRH_HPN_08.6_eng.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Mamaghani, E.; Rahmani, A.; Hassankhani, H.; Zamanzadeh, V.; Camphell, S.; Fast, O.; Irajpour, A. Experiences of Iranian nursing students regarding their clinical learning environment. Asian Nurs. Res. 2018, 12, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadizaker, M.; Abedsaeedi, Z.; Abedi, H.; Saki, A. Design and evaluation of reform plan for local academic nursing challenges using action research. Asian Nurs. Res. 2016, 10, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dağ, G.S.; Kılıç, H.F.; Görgülü, R.S. Difficulties in clinical nursing education: Views of nurse instructors’. Int. Arch. Nurs. Health Care 2019, 5, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Papastavrou, E.; Dimitriadou, M.; Tsangari, H.; Andreou, C. Nursing students’ satisfaction of the clinical learning environment: A research study. BMC Nurs. 2016, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Yang, L.; Pan, Y.; Chen, S. Proactive personality, professional self-efficacy and academic burnout in undergraduate nursing students in China. J. Prof. Nurs. 2021, 37, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanzadeh, V.; Jasemi, M.; Valizadeh, L.; Keogh, B.; Taleghani, F. Lack of preparation: Iranian nurses’ experiences during transition from college to clinical practice. J. Prof. Nurs. 2015, 31, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwandari, R.; Afandi, A.; Amini, D.; Ardiana, A.; Kurniawan, D. The Overview of Self-Efficacy Among Nursing Students. Babali Nurs. Res. 2023, 4, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levett-Jones, T.; Pitt, V.; Courtney-Pratt, H.; Harbrow, G.; Rossiter, R. What are the primary concerns of nursing students as they prepare for and contemplate their first clinical placement experience? Nurse Education in Practice 2015, 15, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, H.; Hamooleh, M.M. Nursing students’ experiences regarding nursing process: A qualitative study. Res. Dev. Med. Educ. 2016, 5, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima College of Health Sciences (FCHS). FCHS Curriculum Document; Fatima College of Health Sciences: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- SEHA. Nurses Continue to Play an Integral Role in the UAE’s Response to COVID-19 Across Different Field Hospitals and Screening Centers. 2020. Available online: https://www.abudhabihealthcareguide.com/nurses-continue-play-integral-role-uaes-response-covid-19-across-different-field-hospitals-screening-centers/ (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Nowais, S. SEHA Seeks More Emirati Nurses. The National. 2016. Available online: https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/health/seha-seeks-more-emirati-nurses-1.206671 (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Antig, A.; Arañez, S.; Cañazares, C.; Palompon, D. Nursing Faculty Shortage Impact on Nursing Students: A Descriptive Phenomenological Study. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2024, 2024, 1751942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, J.; Ramjan, L.M.; Hunt, L.; Salamonson, Y. Nursing students′ clinical performance issues and the facilitator’s perspective: A scoping review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 48, 102890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mekkawi, M. Investigation of Undergraduate Nursing Students Readiness to Practice in the UAE. Ph.D. Dissertation, The British University in Dubai, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, 2nd ed.; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aggar, C.; Bloomfield, J.G.; Frotjold, A.; Thomas, T.H.; Koo, F. A time management intervention using simulation to improve nursing students’ preparedness for medication administration in the clinical setting: A quasi-experimental study. Collegian 2018, 25, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinea, S.; Andersen, P.; Reid-Searl, K.; Levett-Jones, T.; Dwyer, T.; Heaton, L.; Flenady, T.; Applegarth, J.; Bickell, P. Simulation-based learning for patient safety: The development of the Tag Team Patient Safety Simulation methodology for nursing education. Collegian 2019, 26, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padden-Denmead, M.; Scaffidi, R.; Kerley, R.; Farside, A. Simulation With Debriefing and Guided Reflective Journaling to Stimulate Critical Thinking in Prelicensure Baccalaureate Degree Nursing Students. J. Nurs. Educ. 2016, 55, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, A.; Foli, K. Student-Centered Reflection During Debriefing. Nurse Educ. 2021, 47, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, S.A.; Malloy, J.A.; Parsons, A.W.; Peters-Burton, E.E.; Burrowbridge, S.C. Sixth-grade students’ engagement in academic tasks. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 111, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, L.; Mills, G.; Airasian, P. Educational Research, 9th ed.; Pearson Education: Paramus, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; SAGE Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima College of Health Sciences (FCHS). Clinical Placement Manual; Fatima College of Health Sciences: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S.; Parmar, R.; Rao, A. Nursing students’ perceptions toward their learning environment and their perceived academic stress. Int. J. Curr. Res. 2018, 7, 2341–2345. [Google Scholar]

- Aboshaiqah, A.; Roco, I.; Pandaan, I.; Baker, O.; Tumala, R.; Silang, J.P. Challenges in the clinical environment: The Saudi student nurses’ experience. Educ. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 3652643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, N.; Manankil-Rankin, L.; Prentice, D.; Hagerman, L.; Draenos, C. Practice readiness of new nursing graduates: A concept analysis. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 37, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, N.; Molazem, Z.; Sharif, F.; Torabizadeh, C.; Najafi Kalyani, M. The challenges of nursing students in the clinical learning environment: A qualitative study. Sci. World J. 2016, 2016, 1846178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, D.; Ratcliff, J.; Tabb, L.; Walter, R. Undergraduate nursing student perceptions of directed self-guidance in a learning laboratory: An educational strategy to enhance confidence and workplace readiness. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 42, 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, V.R.; Terry, P.C.; Moloney, C.; Bowtell, L. Face-to-face instruction combined with online resources improves retention of clinical skills among undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 61, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Kang, H.S.; De Gagne, J.C. Nursing students’ perceptions and experiences of using virtual simulation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2021, 60, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.; McLaughlin, D. Using simulated patients as a learning strategy to support undergraduate nurses to develop patient-teaching skills. Br. J. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whean, T.; Shi, X.; Andony, K.; Yorke, S.; Poonai, S. Evaluating learners’satisfaction following perioperative nursing simulation training/evaluer la satisfaction des apprenants suite a une formation en soins perioperatoires en laboratoire de simulation. Ornac J. 2018, 36, 12–23. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2108012187?sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Handeland, J.A.; Prinz, A.; Ekra, E.M.R.; Fossum, M. The role of manikins in nursing students’ learning: A systematic review and thematic metasynthesis. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 98, 104661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, K.Z. Gender differences and work-related communication in the UAE: A qualitative study. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 9, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cant, R.P.; Cooper, S.J. Use of simulation-based learning in undergraduate nurse education: An umbrella systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 49, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.Y.; Chen, P. The use of the case method to promote reflective thinking in teacher education. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2019, 6, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyani, M.; Jamshidi, N.; Molazem, Z.; Torabizadeh, C.; Sharif, F. How do nursing students experience the clinical learning environment and respond to their experiences? A qualitative study. BMJ 2019, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatinsky, N.; Chachula, K.; Compton, R.M.; Sedgwick, M.; Press, M.M.; Lane, B. Nursing student preference for block versus nonblock clinical models. J. Nurs. Educ. 2017, 56, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, M.; Bagley, T.; Park, T.; Burkot, C.; Mills, J. The impact of clinical placement model on learning in nursing: A descriptive exploratory study. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 34, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmutalib, I.; Seesy, N.; Yousuf, S. Nursing Students’ Opinions on Facilitating and Hindering Factors in the Clinical Training Setting. Am. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafkan, L.; Kalyani, M.N. Nursing students’ experiences of clinical education: A qualitative study. Nurs. Res. Educ. 2018, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finefter-Rosenbluh, I.; Levinson, M. What is wrong with grade inflation (if anything)? Philos. Inq. Educ. 2019, 23, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Questions | Approach | Instrument | Data Analysis | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. What explanations do the nursing students offer regarding their readiness for their nursing practice? | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | A purposeful sample of 13 students |

| 2. How do variations in clinical nursing study plans across diverse contexts impact nursing students’ readiness for their nursing practicum? | Document analysis | Content analysis | A sample of 11 national, regional, and international nursing study plans | |

| 3. What evidence of students’ readiness can be extracted from their clinical evaluations? | Document analysis | Document analysis | A sample of 217 students’ clinicalevaluations |

| Participants | Age | Year of Study | Campus | Nationality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 22 | Fouth | Al Ain | Emirati |

| S2 | 19 | Third | Ajman | Emirati |

| S3 | 23 | Fourth | Abu Dhabi | Emirati |

| S4 | 22 | Fourth | Al Dhafra | Emirati |

| S5 | 20 | Third | Ajman | Jordanian |

| S6 | 21 | Third | Al Ain | Emirati |

| S7 | 22 | Fourth | Al Ain | Emirati |

| S8 | 20 | Third | Al Dhafra | Emirati |

| S9 | 21 | Third | Abu Dhabi | Emirati |

| S10 | 21 | Third | Al Ain | Emirati |

| S11 | 21 | Third | Abu Dhabi | Emirati |

| S12 | 21 | Third | Ajman | Emirati |

| S13 | 20 | Third | Abu Dhabi | Syrian |

| University/College | Country | Co-requisite Lab Courses for Practicum Courses | Co-Requisite Practicum Courses for Major Nursing Courses | Co-Requisite Practicum Courses for Basic Nursing Courses | Start of Clinical Practicum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New York University | USA | Yes | Yes | No | Year 2 |

| Pennsylvania University | USA | Yes | Yes | No | Year 3 |

| University of Alabama | USA | Yes | Yes | No | Year 2 |

| Griffith University | Australia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Year 1 |

| University of Toronto | Canada | No | Yes | Yes | Year 1 |

| University of Manchester | UK | No | Yes | Yes | Year 1 |

| Higher College of Technology | UAE | No | Yes | Yes (Fundamentals of Nursing only) | Year 1 |

| Macmaster University | Canada | No | Yes | No | Year 2 |

| Jordan University | Jordan | No | Yes | No | Year 2 |

| Sharjah University | UAE | No | Yes | No | Year 3 |

| American University of Beirut | Lebanon | No | Yes | No | Year 3 |

| Nursing College | UAE | No | Yes | No | Year 2/ second semester |

| Unsatisfactory Performance | Satisfactory Performance | Excellent or Very Good Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical procedure knowledge | 17.7% | 4.4% | 77.9% |

| Pathophysiology knowledge | 35.5% | 6.6% | 57.9% |

| Pharmacology knowledge | 11.1% | 13.33% | 75.57% |

| Clinical skills | 8.8% | 44.44% | 46.76% |

| Unsatisfactory Performance | Satisfactory Performance | Excellent or Very Good Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical procedure knowledge | 6.6% | 4.0% | 89.4% |

| Pathophysiology knowledge | 25.3% | 5.3% | 60.4% |

| Pharmacology knowledge | 10.6% | 9.3% | 80.1% |

| Clinical skills | 16% | 13.3% | 70.7% |

| Grade Range | Percentage of the Grade |

|---|---|

| Equals or greater than 90% | 8.8% |

| 80–89% | 44.4% |

| 70–79% | 31.1% |

| 60–69 % | 11.10% |

| Less than 60% | 0% |

| Grade Range | Percentage of the Grade |

|---|---|

| Equals or greater than 90% | 32% |

| 80–89% | 36% |

| 70–79% | 20% |

| 60–69 % | 1.30% |

| Less than 60% | 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maalouf, I.; El Zaatari, W. Decoding Readiness for Clinical Practicum: Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Perspectives, Clinical Evaluations, and Comparative Curriculum Variations. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060204

Maalouf I, El Zaatari W. Decoding Readiness for Clinical Practicum: Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Perspectives, Clinical Evaluations, and Comparative Curriculum Variations. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(6):204. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060204

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaalouf, Imad, and Wafaa El Zaatari. 2025. "Decoding Readiness for Clinical Practicum: Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Perspectives, Clinical Evaluations, and Comparative Curriculum Variations" Nursing Reports 15, no. 6: 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060204

APA StyleMaalouf, I., & El Zaatari, W. (2025). Decoding Readiness for Clinical Practicum: Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Perspectives, Clinical Evaluations, and Comparative Curriculum Variations. Nursing Reports, 15(6), 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060204