Employed Caregivers’ Perceptions of Environmental Influences in Residential Dementia Care: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Paradigm

2.2. Context

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Search and Sample Strategy

2.5. Ethical Issues Pertaining to Human Subjects

2.6. Data Collection Process

2.7. Information Sources

2.8. Selection Process

2.9. Data Extraction

2.10. Data Analysis and Synthesis

2.11. Trustworthiness and Risk of Bias

2.12. Reflexivity

3. Results

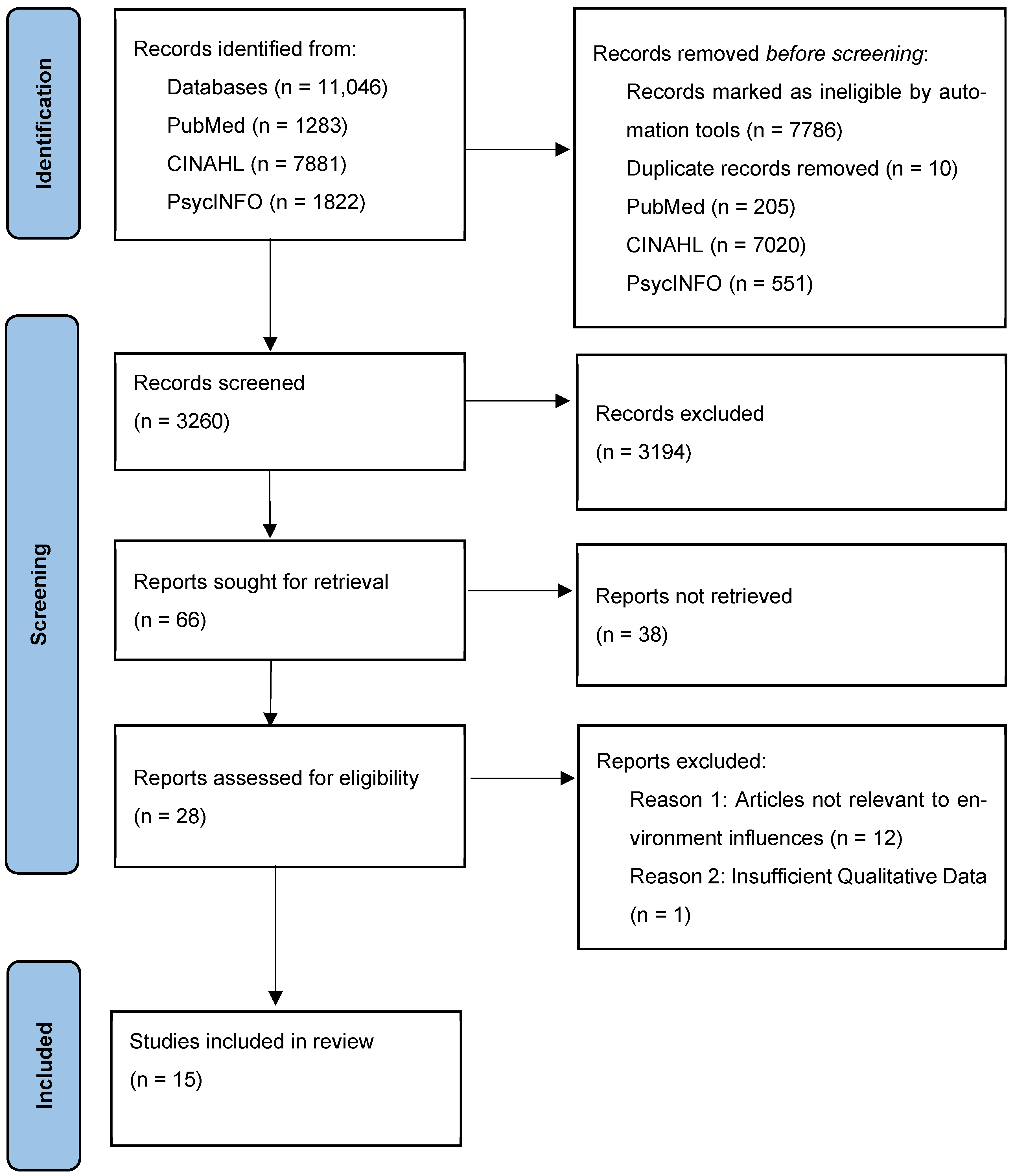

3.1. Results of Screening

3.2. Units of Study

3.3. Quality Appraisal

3.4. Theme Development

3.5. Synthesis and Interpretation

3.5.1. Working Environment: Informed Understanding

Therapeutic Optimism

Comprehending the Job Role

Competence and Confidence

Awareness of Training Needs

Strengthening Job Role Awareness in Practice

3.5.2. Lived Environment: Resistance to Change: Stability and Clarity

Cultural Backgrounds and Stigma

Managing Safety Risks

Moral Distress in Dementia Care

3.5.3. Physical and Built Environment: Impact on Overall Care Experience

Physical Environment and Quality of Life

Building and Interior Design

4. Discussion

5. Implications for Practice and Research

6. Strengths and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Data Base | PubMed | CINALH | PsycINFO |

| Search Terms | ((((((“residential home”[Text Word]) OR (“nursing home”[Text Word])) OR (“residential facilities”[MeSH Major Topic])) OR (“housing for the elderly”[MeSH Major Topic])) AND ((((“dementia”[MeSH Major Topic]) OR (“alzheimer disease”[MeSH Major Topic])) OR (dementia[Text Word])) OR (Alzheimer’s[Text Word]))) AND (((experiences[Text Word]) OR (attitudes[Text Word])) OR (perspectives[Text Word]))) AND (((((((((caregiver*[Text Word]) OR (nurs*[Text Word])) OR (matron[Text Word])) OR (therapist[Text Word])) OR (Manager[Text Word])) OR (“health professional”[Text Word])) OR (“care provider”[Text Word])) OR (“care professional”[Text Word])) OR (“caregivers”[MeSH Major Topic]))) AND (((“qualitative research”[MeSH Major Topic]) OR (interview*[Text Word])) OR (finding*[Text Word]) | ((MH “Nursing Homes/EI/OG/PF/ST”) OR (MH “Home Health Aides/OG/PF/EV/EI”) OR (MH “Nursing Home Patients/PF/EI”) OR “(“residential home”) OR (“nursing home) OR (“residential facilities”) OR (“housing for the elderly”)) AND ((“dementia”) OR (“alzheimer disease”) OR (dementia) OR (Alzheimer’s)) AND ((experiences) OR (attitudes) OR (perspectives)) AND ((caregiver*) OR (nurs*) OR (matron) OR (therapist) OR (Manager) OR (“health professional”) OR (“care provider”) OR (“care professional”) OR (“caregivers”)) AND ((“qualitative research”) OR (interview*) OR (finding*)) AND ((MH “Home Care Equipment and Supplies/OG/EI/ST”) OR (MH “Residential Care”) OR (MH “Caregiver Attitudes”) OR (MH “Housing for Older Persons”) OR (MH “Nursing Home Design and Construction/PF/ES/EI”) OR (MH “Residential Facilities”) OR (MH “Professional-Client Relations”) OR (MH “Professional Practice, Research-Based”) OR (MH “Caregiver Burden”) OR (MH “Home Safety”) OR (MH “Caregiver Emotional Health (Iowa NOC)”) OR (MH “Caregiver Physical Health (Iowa NOC)”) OR (MH “Health Care Delivery”)) | (residential home* OR nursing home* OR residential facilit* OR “housing for the elderly” OR Care home* OR acute care unit*) AND (dementia OR Alzheimer*) AND (caregiver* OR nurs* OR matron* OR therapist* OR Manager* OR “health professional*” OR “healthcare professional*” OR “care provider*” OR “care professional*” OR “caregiver*” OR Care Assistant*) AND (experience* OR attitude* OR perspective* OR view*) AND (qualitative OR interview*) AND la.exact(“English”) AND PEER(yes) |

References

- Shin, J.H. Dementia Epidemiology Fact Sheet 2022. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 46, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvæl, L.A.H.; Bergland, A. The practice environment’s influence on patient participation in intermediate healthcare services—The perspectives of patients, relatives and healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.; Ribeiro, M.; Mendes, M.; Ferreira, R.; Santos, E.; Fassarella, C.; Ribeiro, O. Positive Nursing Practice Environment: A concept analysis. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3052–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenberg, P.A.; MacNeill, S.E.; Mast, B.T. Environmental press and adaptation to disability in hospitalized Live-Alone older adults. Gerontologist 2000, 40, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, M.; Lichtenberg, P.A.; Lysack, C. Environmental press, aging in place, and residential satisfaction of urban older adults. Sociol. Pract. 2006, 8, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soilemezi, D.; Drahota, A.; Crossland, J.; Stores, R. The Role of the Home Environment in Dementia Care and Support: Systematic review of Qualitative Research. Dementia 2017, 18, 1237–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, K.; Carreon, D.; Stump, C. The therapeutic design of environments for people with dementia. Gerontologist 2000, 40, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theorell, T. The Demand Control Support Work Stress model. In Handbook Series in Occupational Health Sciences; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 339–353. Available online: https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-030-31438-5_13 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- de Jonge, J.; Kompier, M.A.J. A Critical Examination of the Demand-Control-Support Model from a Work Psychological Perspective. Int. J. Stress Manag. 1997, 4, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemse, B.M.; De Jonge, J.; Smit, D.; Depla, M.F.I.A.; Pot, A.M. The moderating role of decision authority and coworker- and supervisor support on the impact of job demands in nursing homes: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassbø, T.K.; Kirkevold, M.; Edvardsson, D.; Sjögren, K.; Lood, Q.; Sandman, P.O.; Bergland, Å. Associations between job satisfaction, person-centredness, and ethically difficult situations in nursing homes—A cross-sectional study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 75, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, A.J.; Griffin, R.; Manning, F.; Goodwin, V.A. Support workers knowledge, skills and education relating to dementia—A national survey. NIHR Open Res. 2024, 4, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, K.; Van Diepen, C.; Fors, A.; Axelsson, M.; Bertilsson, M.; Hensing, G. Healthcare professionals’ experiences of job satisfaction when providing person-centred care: A systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e071178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for Reporting Qualitative research. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, J.; McCluskey, S.; Turley, E.; King, N. The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2014, 12, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER Tool for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADI—Dementia Plans. Available online: https://www.alzint.org/what-we-do/policy/dementia-plans/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Leeming, D.; Marshall, J.; Hinsliff, S. Self-conscious emotions and breastfeeding support: A focused synthesis of UK qualitative research. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 18, e13270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, W. High-Stakes testing and curricular Control: A qualitative metasynthesis. Educ. Res. 2007, 36, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASP—Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. 2025. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/qualitative-studies-checklist/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Booi, L.; Sixsmith, J.; Chaudhury, H.; O’Connor, D.; Young, M.; Sixsmith, A. ‘I wouldn’t choose this work again’: Perspectives and experiences of care aides in long-term residential care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3842–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannelly, T.; Gilmour, J.A.; O’Reilly, H.; Leighton, M.; Woodford, A. An ordinary life: People with dementia living in a residential setting. Dementia 2019, 18, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, H.; Hung, L.; Rust, T.; Wu, S. Do physical environmental changes make a difference? Supporting person-centered care at mealtimes in nursing homes. Dementia 2016, 16, 878–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, B.; Verbeek, H.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Hamers, J.P.H. Experiences of family caregivers in green care farms and other nursing home environments for people with dementia: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, L.J.; Hébert, M.; Kozak, J.; Sénécal, I.; Slaughter, S.E.; Aminzadeh, F.; Dalziel, W.; Charles, J.; Eliasziw, M. Perceptions of family and staff on the role of the environment in long-term care homes for people with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadri, A.; Rapaport, P.; Livingston, G.; Cooper, C.; Robertson, S.; Higgs, P. Care workers, the unacknowledged persons in person-centred care: A secondary qualitative analysis of UK care home staff interviews. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killett, A.; Burns, D.; Kelly, F.; Brooker, D.; Bowes, A.; La Fontaine, J.; Latham, I.; Wilson, M.; O’Neill, M.A. Digging deep: How organisational culture affects care home residents’ experiences. Ageing Soc. 2014, 36, 160–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.; Patterson, T.G.; Muers, J. Experiences of healthcare assistants working with clients with dementia in residential care homes. Dementia 2017, 18, 644–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Chaudhury, H.; Hung, L. Exploring staff perceptions on the role of physical environment in dementia care setting. Dementia 2014, 15, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midtbust, M.H.; Gjengedal, E.; Alnes, R.E. Moral distress—A threat to dementia care? A qualitative study of nursing staff members’ experiences in long-term care facilities. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K.; D’Cruz, R.; Harman, S.; Stagnitti, K. Comparison of a traditional and non-traditional residential care facility for persons living with dementia and the impact of the environment on occupational engagement. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2015, 62, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, R.; Brewer, G. Care assistant experiences of dementia care in long-term nursing and residential care environments. Dementia 2015, 15, 1737–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zadelhoff, E.; Verbeek, H.; Widdershoven, G.; Van Rossum, E.; Abma, T. Good care in group home living for people with dementia. Experiences of residents, family and nursing staff. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 2490–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, H.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Van Rossum, E.; Kempen, G.I.J.M.; Hamers, J.P.H. Small-scale, homelike facilities in dementia care: A process evaluation into the experiences of family caregivers and nursing staff. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 49, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoof, J.; Verbeek, H.; Janssen, B.M.; Eijkelenboom, A.; Molony, S.L.; Felix, E.; Nieboer, K.A.; Zwerts-Verhelst, E.L.M.; Sijstermans, J.J.W.M.; Wouters, E.J.M. A three-perspective study of the sense of home of nursing home residents: The views of residents, care professionals and relatives. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polacsek, M.; Goh, A.; Malta, S.; Hallam, B.; Gahan, L.; Cooper, C.; Low, L.F.; Livingston, G.; Panayiotou, A.; Loi, S.; et al. ‘I know they are not trained in dementia’: Addressing the need for specialist dementia training for home care workers. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 28, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, A.M.; Polacsek, M.; Malta, S.; Doyle, C.; Hallam, B.; Gahan, L.; Low, L.F.; Cooper, C.; Livingston, G.; Panayiotou, A.; et al. What constitutes ‘good’ home care for people with dementia? An investigation of the views of home care service recipients and providers. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivett, E.; Hammond, L.; West, J. What influences self-perceived competence and confidence in dementia care home staff? A systematic review. Psychogeriatrics 2019, 19, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, L.; Chan, H.Y. Dementia care education interventions on healthcare providers’ outcomes in the nursing home setting: A systematic review. Res. Nurs. Health 2021, 44, 891–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreier, A.; Thyrian, J.R.; Eichler, T.; Hoffmann, W. Qualifications for nurses for the care of patients with dementia and support to their caregivers: A pilot evaluation of the dementia care management curriculum. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 36, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, K.J.; Forsythe, D.; Wagner, J.; Eckert, M. Clinical pathways for the evidence-based management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in a residential aged care facility: A rapid review. Australas. J. Ageing 2021, 40, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggenberger, E.; Heimerl, K.; Bennett, M.I. Communication skills training in dementia care: A systematic review of effectiveness, training content, and didactic methods in different care settings. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 25, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt, S.R.; Van Der Steen, J.T.; Schols, J.M.G.A.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Pieters, S.; Meijers, J.M.M. Nursing staff needs in providing palliative care for people with dementia at home or in long-term care facilities: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 96, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, A.; Lobo, E.; De-La-Cámara, C. Dementia care in high-income countries. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2019, 32, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyrian, J.R.; Hertel, J.; Wucherer, D.; Eichler, T.; Michalowsky, B.; Dreier-Wolfgramm, A.; Zwingmann, I.; Kilimann, I.; Teipel, S.; Hoffmann, W. Effectiveness and safety of dementia care management in primary care. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Ko, Y.M.; Chen, H.Y.; Chueh, J.W.; Chen, P.Y.; Cooper, C.L. Patient Safety and Staff Well-Being: Organizational Culture as a resource. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantle, C.C.R. Using Risk Management to Promote Person-Centred Dementia Care. Available online: https://journals.rcni.com/nursing-standard/using-risk-management-to-promote-personcentred-dementia-care-ns.30.28.41.s47 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Mannion, R.; Davies, H. Understanding organisational culture for healthcare quality improvement. BMJ 2018, 363, k4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspar, S.; Davis, E.; Berg, K.; Slaughter, S.E.; Keller, H.; Kellett, P. Stakeholder engagement in practice change: Enabling Person-Centred mealtime experiences in residential care homes. Can. J. Aging/La Rev. Can. Du Vieil. 2020, 40, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoye, C.T.; Gebrye, T.; Fatoye, F. The Effectiveness of Personalisation on health Outcomes of Older people: A Systematic review. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2021, 32, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J.; Cronin, C.; Stiell, M.; Ojo, O. The intersection of culture in the provision of dementia care: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 27, 3241–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churruca, K.; Falkland, E.; Saba, M.; Ellis, L.A.; Braithwaite, J. An integrative review of research evaluating organisational culture in residential aged care facilities. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J.; Semlyen, J. Exploring the impact of dementia-friendly ward environments on the provision of care: A qualitative thematic analysis. Dementia 2017, 18, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowaskie, D.Z.; Sewell, D.D. Assessing the LGBT cultural competency of dementia care providers. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2021, 7, e12137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brijnath, B.; Antoniades, J.; Cavuoto, M. Inclusive dementia care for ethnically diverse families. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2023, 36, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatnawi, E.; Steiner-Lim, G.Z.; Karamacoska, D. Cultural inclusivity and diversity in dementia friendly communities: An integrative review. Dementia 2023, 22, 2024–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Kim, J. Influence of caregivers’ psychological well-being on the anxiety and depression of care recipients with dementia. Geriatr. Nurs. 2023, 55, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhet, A.K.; Garnier-Villarreal, M. Effects of positive thinking on dementia caregivers’ burden and Care-Recipients’ behavioral problems. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2019, 42, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, M.; Kim, K. Lasting impact of relationships on caregiving difficulties, burden, and rewards. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2022, 40, 288–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, D. Person-Centered Dementia care: The legacy of Tom Kitwood. Int. J. Pers. Centered Med. 2024, 12, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertshaw, D.; Cross, A. Roles and responsibilities in integrated care for dementia. J. Integr. Care 2018, 27, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dys, S.; Tunalilar, O.; Hasworth, S.; Winfree, J.; White, D.L. Person-centered care practices in nursing homes: Staff perceptions and the organizational environment. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 43, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram—PRISMA Statement. PRISMA Statement. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020-flow-diagram (accessed on 5 May 2025).

| Framework | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| S | Nursing and allied health and social care employees in residential dementia care homes, such as unit managers, health care assistants, nursing assistants, and nurses. Inclusive of both male and female participants aged 18+ with at least 12+ months experience. There were no restrictions on the country of origin to ensure cultural sensitivity and applicability across diverse settings, identifying gaps in research by considering countries with national dementia plans [17]. | Retired staff Less than 12 months experience |

| PI | Employed Caregivers’ perceptions and experiences of the environment’s influence on dementia care practice. | Exclusion criteria involved studies that did not report experiences related to the environment in dementia care. |

| D | This study included qualitative approaches such as interview data, focusing on peer-reviewed, empirical studies published between 2009 and 2024. This time frame accounts for significant socio-economic events like the financial crisis of 2007–2009 and the COVID-19 pandemic, which impacted dementia care environments. These socio-economic shifts influenced funding, resources, and care practices. Therefore, urging adaptive and sustainable care models, making studies from this period particularly relevant. Research prior to 2009 may not reflect these key shifts. | Statistical data |

| E | Qualitative Data and Findings Interview data | |

| R | Qualitative Research | Solely Quantitative Studies |

| Author and Year of Publication | Country | Study Aims | Methods of Data Collection and Analysis | Themes Found | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref. [21] Booi, L., Sixsmith, J., Chaudhury, H., O’Connor, D., Young, M., & Sixsmith, A. (2021). | Canada | To gain insight into the everyday realities facing care aides working in long-term residential care and how they perceive society. | A qualitative ethnographic case study Semi-structured interviews Thematic Analysis | Lack of training Support Appreciation care aides felt about their role | Highlights societal ageism, gendered body care work, and the tension between relational connections needing time and economic profit. |

| Ref. [22] Brannelly, T., Gilmour, J. A., O’Reilly, H., Leighton, M., & Woodford, A. (2019). | UK | To explore the experiences of care support and family members on the impact of a new care approach in a specialised unit as it shifted to an inclusive model. | Qualitative thematic approach Focus Groups Thematic Analysis | Personalised care for people with dementia. Family involvement Continuing to care Staff competence Confidence to care | Participants identified effective working methods that benefited both staff and families and reported improved well-being for individuals with dementia in the unit. |

| Ref. [23] Chaudhury, H., Hung, L., Rust, T., & Wu, S. (2016). | Canada | To examine the impact of environmental renovations in dining spaces of a long-term care facility on residents’ mealtime experience and staff practice in two care units. | Ethnographic observations. Staff Survey Observational Data | Autonomy Personal control Comfort of homelike environment Conducive to social interaction increased personal support. effective teamwork | Physical environmental renovations yield positive outcomes for both residents and staff, additionally facilitating improved person-centred care for all involved. |

| Ref. [24] De Boer, B., Hamers, J. P., Zwakhalen, S. M., Tan, F. E., Beerens, H. C., & Verbeek, H. (2019). | Netherlands | To explore from the perspectives of the informal caregivers of people with dementia, the positive and negative experiences with diverse types of nursing homes. | Semi-structured interviews Exploratory research design Thematic Analysis Phenomenological approach | Experiences with the care environment. The physical environment and atmosphere Activities Person-centred care Communication Staff | The experiences of caregivers in nursing homes vary based on the specific nursing home and the individual nursing staff. |

| Ref. [25] Garcia, L. J., Hébert, M., Kozak, J., et al. (2012) | Canada | To explore the perceptions of family and staff members on the potential contribution of environmental factors that influence disruptive behaviours and quality of life of residents with dementia living in long-term care homes. | Qualitative Focus groups | Facility, staffing, and resident factors to consider when creating optimal environments. Human environments were seen as more important than physical environments, and flexibility was judged essential. Noise was identified as one of the most crucial factors influencing behaviour and quality of life of residents | Mnemonic for key environmental factors (CAREFUL): consistency, approach, staff-to-resident ratio, environmental design, flexibility, understanding, and noise level. |

| Ref. [26] Kadri, A., Rapaport, P., Livingston, G., Cooper, C., Robertson, S., & Higgs, P. (2018). | UK | To explore how the personhood of paid carers of people with dementia can be understood by focussing on the views and experiences of care home staff. | Secondary Qualitative Analysis Interviews | Delivering PCC: issues related to dementia. Issues relating to organisation. Identity of care staff. Views of care role. | Oversight of care staff can turn care work into mere tasks, lower self-efficacy, and obstruct individual-centred care. Many care staff are not recognised individually by their employers, and the moral aspects of formal care work often go unacknowledged. |

| Ref. [27] Killett, A., Burns, D., Kelly, F., Brooker, D., Bowes, A., La Fontaine, J., Latham, I., Wilson, M., & O’neill, M. (2014). | UK | What are the individual circumstances, organisational cultures, and practices most likely to encourage, or inhibit, the provision of high-quality care for older people living in residential and nursing homes? | Interviews Observations | 7 values, attitudes, and behaviours named. | Seven inter-related cultural elements were key to the importance of care quality. |

| Ref. [28] Law, K., Patterson, T. G., & Muers, J. (2017). | UK | To explore the experiences of health care assistants working with people with dementia in UK residential care homes. | IPA Semi-structured interviews | The importance of relationships Something special about the role Personal commitment to the job The other side of caring | Staff should build strong, supportive relationships in their roles and have opportunities to explore their emotional responses to minimise negative effects on care provision. |

| Ref. [29] Lee, S. Y., Chaudhury, H., & Hung, L. (2014). | Canada | To explored staff perceptions of the role of physical environment in dementia care facilities in affecting resident’s behaviours and staff care practice. | Focus groups | A supportive physical environment contributes positively to both quality of staff care interaction and residents’ quality of life Unsupportive physical environments contribute negatively to residents’ quality of life and thereby make the work of staff more challenging | A staff collective view that comfort, familiarity, and an organised space were essential therapeutic resources for the well-being of residents. |

| Ref. [30] Midtbust, M. H., Gjengedal, E., & Alnes, R. E. (2022). | Norway | To gain a deeper understanding of nursing staff members’ experiences of moral distress while providing palliative care for residents with severe dementia in long-term care facilities. | Qualitative descriptive design Thematic Analysis In-depth interviews | Experiences of moral distress in two types: Those in which nursing staff members felt pressured to provide futile end-of-life treatment. Those who felt that they had been prevented from providing necessary care and treatment | Moral distress often arises from institutional constraints like time limits, challenging priorities, and value conflicts. |

| Ref. [31] Richards, K., D’Cruz, R., Harman, S., & Stagnitti, K. (2015). | Australia | To compare these two environments in rural Australia, and their. Influence on residents’ occupational engagement. | The residential environment impact survey Observations Interviews Thematic Analysis | Comfortable environment Roles and responsibilities Getting to know the resident. More stimulation can elicit increased engagement. The home-like experience. Environmental layout. | Research shows that non-traditional dementia facilities enhance occupational involvement, leading to positive outcomes. |

| Ref. [32] Talbot, R., & Brewer, G. (2015). | UK | To address the paucity of research in this area, the present study examined care assistant experiences of dementia care in British long-term residential and nursing environments. | Semi-structured interviews IPA | Psychological wellbeing of the care assistant. Barriers to effective dementia care The dementia reality Organisational issues within the care environment | The benefits of the care dyad were noted, and the organisation’s role in causing burnout and depersonalisation was emphasised. |

| Ref. [33] Van Zadelhoff, E., Verbeek, H., Widdershoven, G., van Rossum, E., & Abma, T. (2011). | Netherlands | To investigate experiences of residents, their family caregivers, and nursing staff in group living homes for older people with dementia and their perception of the care process. | Naturalist design Systematic participatory observations Semi-structured interviews | Residents Family Nursing Staff | Group living homes provide opportunities for individual care, meeting residents’ needs with increased attentiveness. This aligns with Tronto’s care ethical model phases of caring about and receiving care. However, tensions arise in taking responsibility and performing self-care, as not all residents and family members can or want to do so. |

| Ref. [34] Verbeek, H., Zwakhalen, S. M., van Rossum, E., Kempen, G. I., & Hamers, J. P. (2011). | Netherlands | To gain an in-depth insight into the experiences of family caregivers and nursing staff with small-scale living facilities | Interviews Survey questionnaire | Family Caregivers Positive aspects of small-scale living facilities Experiences with care service delivery Homeliness in small-scall facilities. Nursing Staff Skills Negative aspects of small-scale facilities Positive aspects of working in a small-scale living facility. Negative aspects of working in a small-scale living facility. | Both family caregivers and staff reported positive experiences with small-scale living facilities, highlighting personal attention, resident involvement, and autonomy. However, barriers include nursing staff working alone much of the day. Family caregivers in these facilities were more satisfied than those in regular wards. |

| Ref. [35] Van Hoof, J., Verbeek, H., Janssen, B. M., Eijkelenboom, A., Molony, S. L., Felix, E., Nieboer, K. A., Zwerts-Verhelst, E. L., Sijstermans, J. J., & Wouters, E. J. (2016). | Netherlands | To investigate the factors influencing the sense of home of older adults living in the nursing home from the perspective of residents, relatives, and care professionals. | Focus groups. Interviews Photography as a supportive tool | Building and interior design Eating and drinking Autonomy and control Involvement of residents Engagement with others and activities Quality of care Connection with nature and outdoors Coping Organisation and facilitative of care To matter | The sense of home for nursing home residents is influenced by building design, eating and drinking, autonomy and control, involvement of relatives and others, activities, and the quality of care. |

| Author and Year of Publication | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref. [21] Booi, L., Sixsmith, J., Chaudhury, H., O’Connor, D., Young, M., & Sixsmith, A. (2021). | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | 9 |

| Ref. [22] Brannelly, T., Gilmour, J. A., O’reilly, H., Leighton, M., & Woodford, A. (2019). | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | Y | Y | 8 |

| Ref. [23] Chaudhury, H., Hung, L., Rust, T., & Wu, S. (2016). | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Ref. [24] De Boer, B., Verbeek, H., Zwakhalen, S. M. G., & Hamers, J. P. H. (2019). | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | Y | Y | 7 |

| Ref. [25] Garcia, L. J., Hébert, M., Kozak, J., Sénécal, I., Slaughter, S. E., Aminzadeh, F., Dalziel, W., Charles, J., & Eliasziw, M. (2012) | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | Y | Y | 6 |

| Ref. [26] Kadri, A., Rapaport, P., Livingston, G., Cooper, C., Robertson, S., & Higgs, P. (2018) | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Ref. [27] Killett, A., Burns, D., Kelly, F., Brooker, D., Bowes, A., La Fontaine, J., Latham, I., Wilson, M., & O’Neill, M. A. (2014). | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Ref. [28] Law, K., Patterson, T. G., & Muers, J. (2017) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Ref. [29] Lee, S. Y., Chaudhury, H., & Hung, L. (2014) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Ref. [30] Midtbust, M. H., Gjengedal, E., & Alnes, R. E. (2022) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Ref. [31] Richards, K., D' Cruz, R., Harman, S., & Stagnitti, K. (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Ref. [32] Talbot, R., & Brewer, G. (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Ref. [33] Van Zadelhoff, E., Verbeek, H., Widdershoven, G., van Rossum, E., & Abma, T. (2011) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | 9 |

| Ref. [34] Verbeek, H., Zwakhalen, S. M. G., van Rossum, E., Kempen, G. I. J. M., & Hamers, J. P. H. (2011) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Ref. [35] Van Hoof, J., Verbeek, H., Janssen, B. M., Eijkelenboom, A., Molony, S. L., Felix, E., Nieboer, K. A., Zwerts-Verhelst, E. L. M., Sijstermans, J. J. W. M., & Wouters, E. J. M. (2016). | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | 9 |

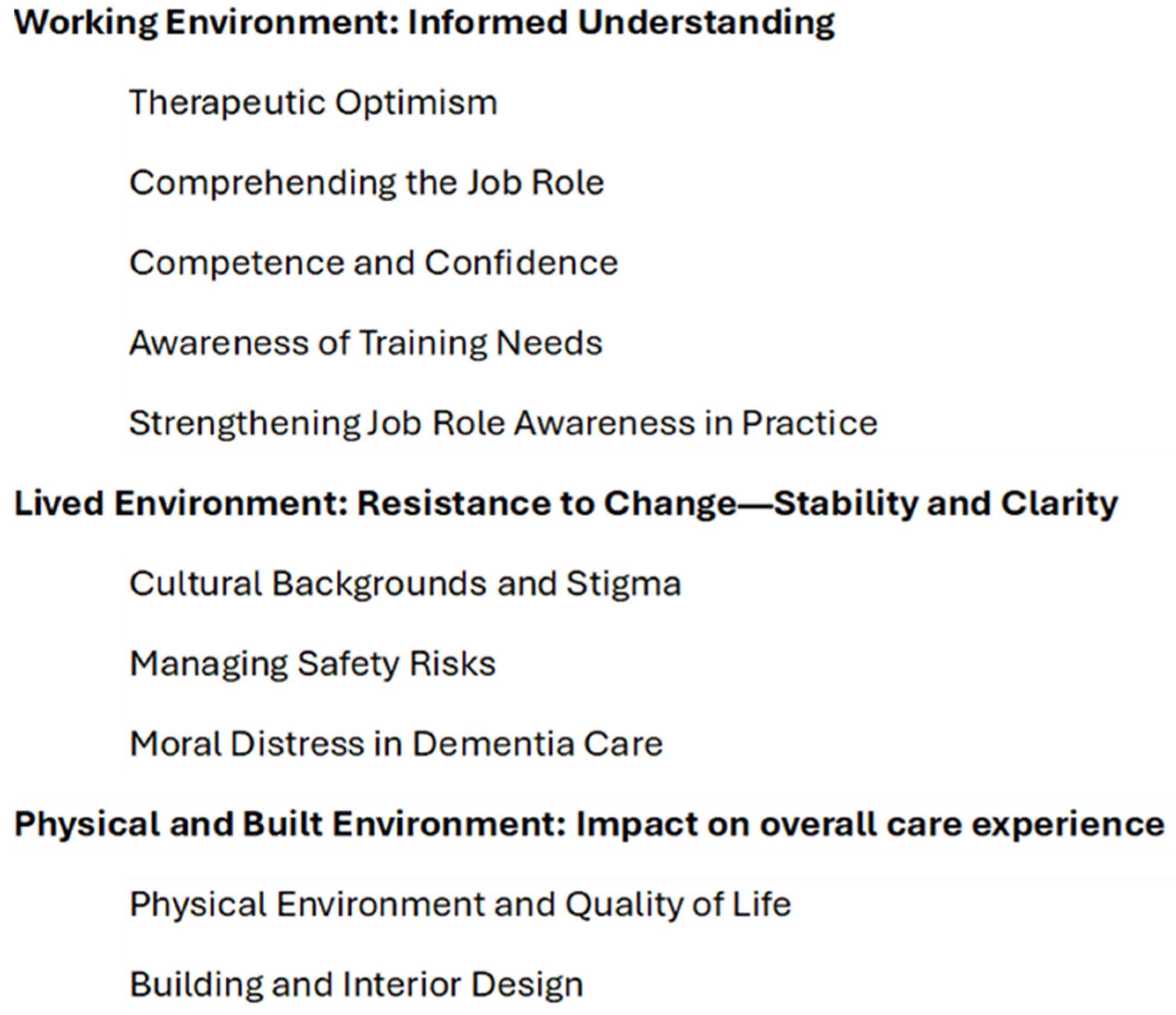

| Working Environment: Informed Understanding The theme of the Working Environment: informed understanding has embraced and combined important practices/concepts in healthcare such as informed decision making and informed consent, etc. Working Environment: Informed understanding has a deeper meaning in that it values the idea that information is central to Employed Caregivers, with the level of understanding being the essential element required for a positive outcome in the work environment. For example, when an informed understanding is present, the following subthemes can be successfully implemented in practice. |

| Therapeutic Optimism |

| Comprehending the Job Role |

| Competence and Confidence |

| Awareness of Training Needs |

| Strengthening Job Role Awareness in Practice |

|

Lived Environment: Resistance to Change: Stability and Clarity Resistance to change in daily life can be attributed to certain key experiences. Employed Caregivers need for stability and clarity is influenced by the following themes found in their daily encounters. These themes contributed to difficulties in maintaining stability and clarity in the lived environment. Regular occurrences of the following subthemes increased environmental pressure, which leads to stagnation in some areas and impacts the capacity for stability and clarity. |

| Cultural Backgrounds and Stigma |

| Managing Safety Risks |

| Moral Distress in Dementia Care |

|

Physical and Built Environment: Impact on overall care experience Employed Caregivers saw how the physical environment affected their work performance, which in turn influenced the overall care experience. A well-designed physical and built environment not only enhanced quality of life for residents but supported Employed Caregivers in performing their duties more effectively. Consequently, the design and layout of a room changed both the quality of care provided and the well-being of the Employed Caregivers. |

| Physical Environment and Quality of Life |

| Building and Interior Design |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Downes, M.N.; Hemingway, S.; Simkhada, B.; King, N.; Caress, A.-L. Employed Caregivers’ Perceptions of Environmental Influences in Residential Dementia Care: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060183

Downes MN, Hemingway S, Simkhada B, King N, Caress A-L. Employed Caregivers’ Perceptions of Environmental Influences in Residential Dementia Care: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(6):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060183

Chicago/Turabian StyleDownes, Megan Nicola, Steve Hemingway, Bibha Simkhada, Nigel King, and Ann-Louise Caress. 2025. "Employed Caregivers’ Perceptions of Environmental Influences in Residential Dementia Care: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis" Nursing Reports 15, no. 6: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060183

APA StyleDownes, M. N., Hemingway, S., Simkhada, B., King, N., & Caress, A.-L. (2025). Employed Caregivers’ Perceptions of Environmental Influences in Residential Dementia Care: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. Nursing Reports, 15(6), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060183