Examining Factors Associated with Attrition, Strategies for Retention Among Undergraduate Nursing Students, and Identified Research Gaps: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the most common reported factors contributing to attrition among students enrolled in Bachelor of Nursing programs?

- What strategies have been implemented or proposed to improve retention in bachelor-level nursing education?

- What gaps exist in the current literature regarding nursing student attrition and retention strategies at the bachelor level?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identifying the Research Question

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

Data Sources and Search Strategy

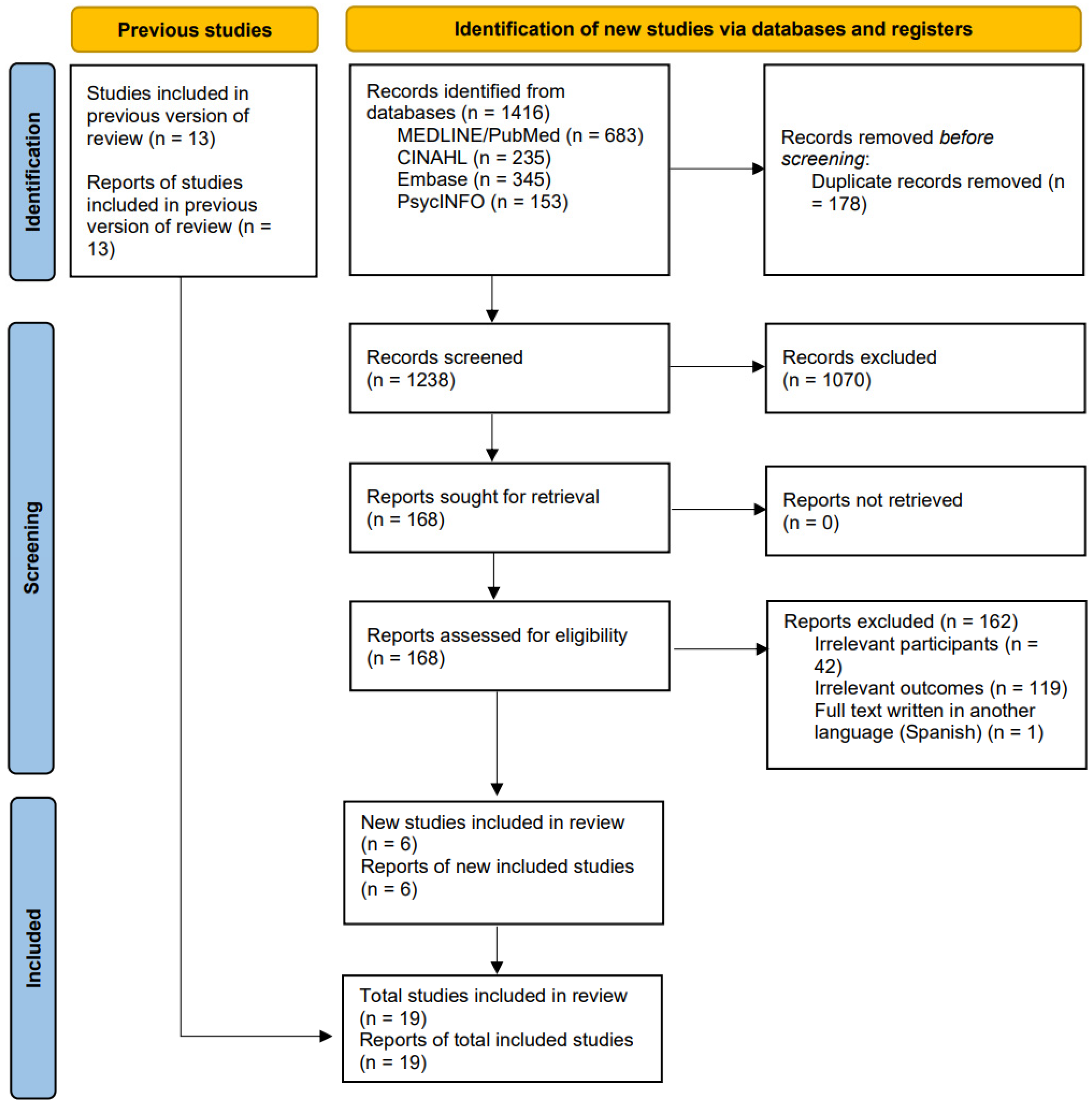

2.3. Study Selection

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Studies focused on students enrolled in bachelor-level (BSN or equivalent) nursing programs of 3–4 years’ duration.

- Studies addressing attrition-related outcomes such as dropout, intention to leave, or retention.

- Peer-reviewed empirical studies (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods).

- Published in English between 2010 and 31 December 2024.

- Conducted in any country to capture global patterns.

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Studies focusing on non-nursing students, or nursing education at diploma, associate, or graduate levels.

- Grey literature, unpublished studies, editorials, commentaries, protocols, letters, or abstracts without primary data.

- Studies not addressing attrition, dropout, or retention.

- Articles not available in English.

2.4. Data Charting and Extraction

2.5. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

2.6. Quality Appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies

3.2. Factors Associated with Attrition

3.2.1. Academic Factors

3.2.2. Institutional and Social Support

3.2.3. Personal Factors

3.2.4. Economic Challenges

3.3. Strategies for Retention

3.3.1. Academic Strategies

3.3.2. Nonacademic Strategies

3.4. Research Gaps, Future Directions, and Practical Implications

| Author(s), Year, Country | Identified Gaps | Suggestions for Future Research | Implications for Practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abele et al., 2013, USA [19] | Lack of studies examining non-nursing courses (e.g., psychology) as predictors of success among at-risk nursing students Limited research focusing specifically on academically probationary students in nursing programs | Explore the role of critical thinking development via interdisciplinary course collaboration in improving nursing student outcomes | Monitoring course performance (e.g., psychology) and identify at-risk students early for intervention Implementing mentorship, student-to-student support, and critical thinking courses to improve retention and academic success |

| Ashghali Farahani et al., 2017, Iran [29] | Lack of preparation and awareness before entering nursing education Discrepancy between expectations and realities in both theoretical and clinical education Lack of support and professional identity Clinical settings not prepared to support student learning Poor student supervision and workforce planning | Explore institutional interventions and policy changes to reduce attrition Longitudinal research is needed to examine the long-term impact of clinical experiences on student retention | Enhance pre-nursing career guidance Improve theoretical and clinical coordination Strengthen faculty training and supervision Promote a supportive and respectful learning environment in clinical practice Address gender-specific challenges and professional identity formation |

| Bakker et al., 2021, The Netherlands [21] | Limited longitudinal studies examining the effects of psychosocial work characteristics on nursing student attrition Lack of research on changes in distress and intention to leave over time Lack of research on the impact of offensive behaviors such as workplace violence on nursing student distress and dropout Need for further exploration of protective factors such as co-worker and supervisor support in clinical settings | Longitudinal studies to assess the long-term impact of workplace violence and psychological demands on student dropout Development of interventions aimed at improving the psychosocial work climate in clinical placements Exploring the role of faculty and organizational policies in mitigating distress and dropout among nursing students | Improve the psychosocial work environment of nursing students. Enhancing co-worker and supervisor support to reduce nursing students’ intention to leave Reducing workplace violence and psychological demands in clinical placements Improve co-worker support alongside supervisor support Attention should be given to nursing students’ psychological strain and exposure to violence during clinical placements |

| Barbé et al., 2018, USA [35] | Limited data on early predictors of attrition at the end of the first semester There is a need for improved identification of at-risk students from diverse backgrounds | Examining how self-perceptions of nursing students impact attrition and what strategies support confidence and persistence Examining whether overlapping factors can be combined into a risk index to improve prediction and guide targeted interventions | Systematic attention should be given to social determinants among students in nursing programs Early identification of at-risk students using academic and psychosocial indicators Development of support programs targeting English language support, financial aid, and confidence-building measures for minority students |

| Canzan et al., 2022, Italy [3] | Limited data on the effectiveness of mentorship programs Lack of studies on students who considered leaving but stayed | Further exploration in other nursing academic settings is needed in order to give a deep understanding of the nursing student attrition Exploring the effectiveness of strategies to improve nursing students’ intention to stay | Strengthen mentorship initiatives in nursing education programs |

| Dancot et al., 2021, Belgium [33] | Self-esteem is rarely measured at the start of nursing education The link between self-esteem, state anxiety, self-efficacy and dropout has been underexplored Further research of self-esteem and dropout using Mruk’s two-dimensional self-esteem is suggested | Conduct longitudinal, mixed-methods studies to explore self-esteem dynamics over time Model the system of factors influencing self-esteem and dropout Compare nursing students with other student populations. Further explore the relevance of self-esteem profiles | Institutions should support student self-esteem early on, especially for those with anxiety or low self-efficacy Improve communication and support systems to foster a sense of belonging Follow first-year nursing students monthly Consider self-esteem in dropout prevention efforts |

| Kox et al., 2022, The Netherlands [22] | Lack of qualitative insights on student dropout Unclear causal link between intention to leave and actual dropout | Explore interventions that foster a supportive workplace culture Conduct qualitative studies to explore reasons for dropout and intention to leave Examine gender-related dropout risks, especially among male students Investigate the impact of severity of musculoskeletal complaints Systematic exit interviews or surveys with students that have decided to quit nursing education | More attention should be paid to the students’ personal circumstances during nursing education Provide early support for students at risk (e.g., males, those with high distress) Promote co-worker support and decision-making autonomy in clinical placements Offer physical workload and ergonomic training early in nursing education |

| Kukkonen et al., 2016, Finland [27] | Little knowledge on the long-term effects of early intervention programs Lack of a common definition and tracking method for attrition Insufficient identification and support for at-risk students | Not reported | Introduce early interventions that prevent student attrition Schools should create models to recognize and support at-risk students through tailored interventions |

| Matteau et al., 2023, Canada [23] | Limited understanding of how academic conditions influence psychological distress and intention to leave Lack of longitudinal studies on academic stressors and student attrition Lack of studies examining effort-reward imbalance or school-work–life conflict among nursing students | Conduct longitudinal studies to establish causal relationships between academic stressors and attrition Develop and test interventions to reduce school-work–life conflicts and modulate workload. Engage nursing students and faculty in participatory research to identify context-specific challenges Explore overcommitment because of academic workload in nursing education | Implement interventions targeting modifiable academic conditions (e.g., reduce workload, improve work–life balance, increase perceived rewards) improving nursing students’ mental health and retention |

| Mazzotta et al., 2024, Italy [30] | lack of insight into attrition across different institutional and cultural contexts | Conduct research with larger samples in varied educational and cultural contexts to validate and extend findings | Provision of adequate support systems, mentorship, and resources for students Enhance the quality and relevance of clinical learning experiences Introduce financial assistance programs for economically disadvantaged students |

| Roos et al., 2016, South Africa [31] | Limited research on nurses’ career satisfaction over time | Analyze long-term career satisfaction and its impact on retention Conduct more detailed and multi-site investigations into the reasons for nursing student attrition in South Africa | Provide career development programs to sustain job satisfaction Strengthen academic and financial support systems; implement wellness interventions and structured orientation programs to improve retention |

| Roso-Bas et al., 2016, Spain [24] | Limited studies focusing on emotional predictors of dropout in nursing students Lack of research on protective emotional factors | Longitudinal studies focusing on the evaluation of emotional variables like optimism and emotional regulation affecting dropout | Integrate emotional intelligence training and psychological support into nursing curricula to reduce dropout risk |

| Sharif-Nia et al., 2023, Iran [25] | Limited research on the impact of bullying behaviors on nursing students’ sense of belonging and academic satisfaction Faculty and clinical instructors’ contribution to bullying in nursing education. Interventions that effectively mitigate bullying and promote student retention | Examine longitudinal impacts of bullying on attrition Effectiveness of intervention programs that enhance student belongingness and major satisfaction to reduce dropout rates | Implement anti-bullying policies that target faculty behavior and clinical instructor interactions Enhance nursing students’ sense of belonging through mentorship programs and peer support networks |

| Soerensen et al., 2023, Denmark [32] | Inadequate preparation for the emotional challenges of clinical placements Social exclusion and lack of belonging were underexplored as dropout factors | Further studies should explore strategies to enhance emotional support and resilience among nursing students Investigate the development of student resilience and the educator’s role in strengthening it. Compare students who dropped out with those who stayed despite similar experiences. | Improve clinical guidance and social inclusion Implement interventions to support students facing emotional and personal stress Foster caring, supportive relationships between educators and students to develop professional identity Create emotionally safe clinical and academic environments that support reflection and resilience |

| Ten Hoeve et al., 2017, The Netherlands [28] | Lack of robust data on why Dutch nursing students consider leaving pre-registration nursing programs. Limited insight into how training organization, quality, and staff support affect dropout rates Insufficient understanding of the impact of team support and integration in clinical placements on student retention | Further qualitative research to better understand student experiences with training programs and clinical placements Examine strategies to reduce theory-practice gap and improve academic-practical integration Investigate the role of team dynamics and student integration into clinical teams | Strengthen cooperation between teaching staff and clinical mentors to support students effectively Improve the structure and content of training programs, ensuring consistency in quality and expectations Recognize and nurture intrinsic motivations while addressing external barriers like poor mentorship or unclear career expectations |

| Van Hoek et al., 2019, Belgium [26] | Insufficient analysis of resilience impact on academic success and attrition | Investigate the predictive value of resilience on long-term success Investigate causal pathways between resilience, mental health history, and dropout Evaluate targeted interventions | Enhance resilience training to support student academic achievement |

| Viottini et al., 2024, Italy [34] | Limited research on the link between motivations for enrolment and dropout among first-year nursing students Few studies combining quantitative and qualitative methods to understand dropout factors Limited studies focus on first-year students or use longitudinal designs | Conduct longitudinal, multicenter studies to analyze dropout trends across different universities Explore effectiveness of interventions aimed at students who enroll in nursing as a second choice Explore strategies to enhance professional identity and belonging among first-year nursing students. | Implement targeted interventions for students who enroll in nursing as a second choice Introduce interventions like peer support, time management training, and mental health strategies Enhance clinical placement experiences to align expectations with real-world nursing practice |

| Williams, 2010, USA [36] | Lack of understanding about how personal mindset and connection-building influence persistence in nursing programs | Examine interventions that enhance early nursing student persistence Conduct multi-site studies on how student engagement with persistence-focused interventions affects retention and graduation | Develop faculty-driven strategies to improve student persistence Create structured opportunities to build student-to-student and student-faculty connections, engage families, support mindset development, and target key stress points early in the program |

| Wray et al., 2017, UK [20] | Inadequate data on factors influencing nurse program completion Limited understanding of how demographic factors like age, dependents, and residency status impact attrition risk | Analyze institutional and personal factors affecting completion rates Explore how individual student characteristics interact with institutional support to influence progression | Establish institutional policies that support student success Early identification of students at risk (e.g., younger, non-local, no dependents) Tailor support to diverse student needs |

4. Discussion

4.1. Academic Challenges

4.2. Institutional and Social Support

4.3. Professional Identity and Perceptions of Nursing as a Career

4.4. Academic Support, Mentoring, and Student Persistence

4.5. Personal Responsibilities, Gender Differences, and Attrition Risks

4.6. Clinical Support and Learning Environments

4.7. Research Gaps and Implications

4.8. Practical and Policy Recommendations

4.9. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BNP | Bachelor Nursing Program |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| PCC | Population/Concept/context |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Scoping Reviews |

| MM | Searches the exact MeSH subject heading; searches just for major headings |

References

- Jones-Berry, S. Student drop-out rates put profession at further risk. Nurs. Stand. 2017, 32, 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HK-dir. Students in Nursing Education—Statistics 6.11 (Studenter i Sykepleierutdanning—Statistikk 6.11) [Data Set]. Database for Statistics on Higher Education (DBH). 2021. Available online: https://dbh.hkdir.no/tall-og-statistikk/statistikk-meny/studenter/statistikk-side/6.11/param?visningId=275&visKode=false&admdebug=false&columns=arstall%218%21arstall_normert&hier=studkode%219%21instkode%219%21progkode&formel=1087%218%211097%218%211091%21 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Canzan, F.; Saiani, L.; Mezzalira, E.; Allegrini, E.; Caliaro, A.; Ambrosi, E. Why do nursing students leave bachelor program? Findings from a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkley, B. Student nurse attrition: A half century of research. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2015, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, N. Failure to complete BSN nursing programs: Students’ views. J. Adv. Educ. Res. Int. 2019, 13, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Veesart, A.; Cannon, S. The lived experience of nursing students who were unsuccessful in an undergraduate nursing program-A narrative inquiry. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 118, 105517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, E.N. A model of nursing student retention. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Sch. 2012, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamata, A.T.; Mohammadnezhad, M.; Tamani, L. Registered nurses’ perceptions on the factors affecting nursing shortage in the Republic of Vanuatu Hospitals: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamata, A.T.; Mohammadnezhad, M. A systematic review study on the factors affecting shortage of nursing workforce in the hospitals. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkutu, N.; Seekoe, E. Factors Associated with Dropout, Retention and Graduation of Nursing Students in Selected Universities in South Africa: A Narrative Review. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2018, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehm, B.M.; Larsen, M.R.; Sommersel, H.B. Student dropout from universities in Europe: A review of empirical literature. Hung. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 9, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal College of Nursing. Nursing Our Future: An RCN Study into the Challenges Facing Today’s Nursing Students in the UK. 2008. Available online: https://docplayer.net/4695163-Nursing-our-future-an-rcn-study-into-the-challenges-facing-today-s-nursing-students-in-the-uk.html (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Marsh, E. Content Analysis: A Flexible Methodology. Libr. Trends 2006, 55, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, C.; Penprase, B.; Ternes, R. A closer look at academic probation and attrition: What courses are predictive of nursing student success? Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, J.; Aspland, J.; Barrett, D.; Gardiner, E. Factors affecting the programme completion of pre-registration nursing students through a three year course: A retrospective cohort study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2017, 24, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, E.J.; Roelofs, P.D.; Kox, J.H.; Miedema, H.S.; Francke, A.L.; van der Beek, A.J.; Boot, C.R. Psychosocial work characteristics associated with distress and intention to leave nursing education among students; A one-year follow-up study. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 101, 104853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kox, J.H.; Runhaar, J.; Groenewoud, J.H.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.; Bakker, E.J.; Miedema, H.S.; Roelofs, P.D. Do physical work factors and musculoskeletal complaints contribute to the intention to leave or actual dropout in student nurses? A prospective cohort study. J. Prof. Nurs. 2022, 39, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteau, L.; Toupin, I.; Ouellet, N.; Beaulieu, M.; Truchon, M.; Gilbert-Ouimet, M. Nursing students’ academic conditions, psychological distress, and intention to leave school: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 129, 105877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roso-Bas, F.; Jiménez, A.P.; García-Buades, E. Emotional variables, dropout and academic performance in Spanish nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 37, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif-Nia, H.; Marôco, J.; Rahmatpour, P.; Allen, K.A.; Kaveh, O.; Hoseinzadeh, E. Bullying behaviors and intention to drop-out among nursing students: The mediation roles of sense of belonging and major satisfaction. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoek, G.; Portzky, M.; Franck, E. The influence of socio-demographic factors, resilience and stress reducing activities on academic outcomes of undergraduate nursing students: A cross-sectional research study. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 72, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkonen, P.; Suhonen, R.; Salminen, L. Discontinued students in nursing education–Who and why? Nurse Educ. Pract. 2016, 17, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Hoeve, Y.; Castelein, S.; Jansen, G.; Roodbol, P. Dreams and disappointments regarding nursing: Student nurses’ reasons for attrition and retention. A qualitative study design. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 54, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, M.A.; Ghaffari, F.; Oskouie, F.; Tafreshi, M.Z. Attrition among Iranian nursing students: A qualitative study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2017, 22, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzotta, R.; Durante, A.; Bressan, V.; Cuoco, A.; Vellone, E.; Alvaro, R.; Bulfone, G. Perceptions of nursing staff and students regarding attrition: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2024, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, E.; Fichardt, A.E.; MacKenzie, M.J.; Raubenheimer, J. Attrition of undergraduate nursing students at selected South African universities. Curationis 2016, 39, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soerensen, J.; Nielsen, D.S.; Pihl, G.T. It’s a hard process—Nursing students’ lived experiences leading to dropping out of their education; a qualitative study. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 122, 105724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancot, J.; Pétré, B.; Dardenne, N.; Donneau, A.; Detroz, P.; Guillaume, M. Exploring the relationship between first-year nursing student self-esteem and dropout: A cohort study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 2748–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viottini, E.; Ferrero, A.; Albanesi, B.; Acquaro, J.; Bulfone, G.; Condemi, F.; D’accolti, D.; Massimi, A.; Mattiussi, E.; Sturaro, R.; et al. Motivations for Enrolment and Dropout of First-Year Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Pilot Multimethod Study. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3488–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbé, T.; Kimble, L.P.; Bellury, L.M.; Rubenstein, C. Predicting student attrition using social determinants: Implications for a diverse nursing workforce. J. Prof. Nurs. 2018, 34, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.G. Attrition and retention in the nursing major: Understanding persistence in beginning nursing students. Nurs. Educ. Perspect 2010, 31, 362–367. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Z.C.; Cheng, W.Y.; Fong, M.K.; Fung, Y.S.; Ki, Y.M.; Li, Y.L.; Wong, H.T.; Wong, T.L.; Tsoi, W.F. Curriculum design and attrition among undergraduate nursing students: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 74, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovdhaugen, E.; Sweetman, R.; Thomas, L. Institutional scope to shape persistence and departure among nursing students: Re-framing Tinto for professional degrees. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2023, 29, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, T.J.; Rolf, C.G.; GPAs, D. Entrance Exams, or Course Grades Predict Outcomes in First Semester Nursing Students? J. Prof. Nurs. 2023, 49, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, C.; Black, P.; Melby, V.; Fitzpatrick, B. An exploration of the predictive validity of selection criteria on progress outcomes for pre-registration nursing programmes-A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 2489–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, P.; Owen, P.A.; Mustafa, N.; Beech, R. Learning and teaching approaches promoting resilience in student nurses: An integrated review of the literature. Nurse Educ Pract. 2020, 45, 102748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, S.; Salamonson, Y.; Weaver, R.; Smith, A.; O’Reilly, R.; Taylor, C. Hate the course or hate to go: Semester differences in first year nursing attrition. Nurse Educ Today 2008, 28, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joolaee, S.; Amiri, S.R.J.; Farahani, M.A.; Varaei, S. Iranian nursing students’ preparedness for clinical training: A qualitative study. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, e13–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Velden, G.J.; Meeuwsen, J.A.L.; Fox, C.M.; Stolte, C.; Dilaver, G. Peer-mentorship and first-year inclusion: Building belonging in higher education. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, M.; Wayne, I.; Persutte-Manning, S.; Pergantis, S.; Vaughan, A. Enhancing student outcomes: Peer mentors and student transition. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 2022, 34, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, E.J.; Verhaegh, K.J.; Kox, J.H.; van der Beek, A.J.; Boot, C.R.; Roelofs, P.D.; Francke, A.L. Late dropout from nursing education: An interview study of nursing students’ experiences and reasons. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 39, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffreys, M.R. Jeffreys’s Nursing Universal Retention and Success model: Overview and action ideas for optimizing outcomes A-Z. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, S.; Momino, K. Stress Factors and Coping Behaviors in Nursing Students during Fundamental Clinical Training in Japan. Int. J. Nurs. Clin. Pract. 2015, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Everett, M.C. Sharing the Responsibility for Nursing Student Retention. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2020, 15, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.M.; Baxter, C.E.; Gural, D.M.; Chorney, M.A.; Simmons-Swinden, J.M.; Queau, M.L.; Nayak, N. Strategies for retention of nursing students: A scoping review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 50, 102956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. State of the World’s Nursing 2020: Investing in Education, Jobs and Leadership (No. 9789240003279). 2020. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/331677/9789240003279-eng.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Tinto, V. Dropout from Higher Education: A Theoretical Synthesis of Recent Research. Rev. Educ. Res. 1975, 45, 89–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesje, K.; Wiers-Jenssen, J. Initial motivation and drop-out in nursing and business administration programmes. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2023, 29, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Noumani, H.; Al Zaabi, O.; Arulappan, J.; George, H.R. Professional identity and preparedness for hospital practice among undergraduate nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 133, 106044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamshidi, N.; Molazem, Z.; Sharif, F.; Torabizadeh, C.; Kalyani, M.N. The Challenges of Nursing Students in the Clinical Learning Environment: A Qualitative Study. Sci. World J. 2016, 2016, 1846178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Wang, W. The Role of Academic Resilience, Motivational Intensity and Their Relationship in EFL Learners’ Academic Achievement. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 823537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekan, D.A.; Ward, T.D.; Elliott, A.A. Resilience in Baccalaureate Nursing Students: An Exploration. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2018, 56, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, A.; Correia, N.; Zaccoletti, S.; Daniel, J.R. Anxiety and Social Support as Predictors of Student Academic Motivation During the COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 644338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avilés-González, C.I.; Curcio, F.; Dal Molin, A.; Casalino, M.; Finco, G.; Galletta, M. Relationship between tutor support, caring self-efficacy and intention to leave of nursing students: The roles of self-compassion as mediator and moderator. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2024, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; Wheat, M.; Christensen, M.; Craft, J. Snaps(+): Peer-to-peer and academic support in developing clinical skills excellence in under-graduate nursing students: An exploratory study. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 73, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neiterman, E.; Beggs, B.; HakemZadeh, F.; Zeytinoglu, I.; Geraci, J.; Plenderleith, J.; Lobb, D. Can peers improve student retention? Exploring the roles peers play in midwifery education programmes in Canada. Women Birth 2023, 36, e453–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Stake-Doucet, N.; Lombardo, C.; Sanzone, L.; Tsimicalis, A. An Integrative Review of Peer Mentorship Programs for Undergraduate Nursing Students. J. Nurs. Educ. 2016, 55, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glew, P.J.; Ramjan, L.M.; Salas, M.; Raper, K.; Creed, H.; Salamonson, Y. Relationships between academic literacy support, student retention and academic performance. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 39, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, D.; Gladstone, N. Exploring support strategies for improving nursing student retention. Nurs. Stand. 2022, 37, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.-L.; Wang, T.; Bressington, D.; Easpaig, B.N.G.; Wikander, L.; Tan, J.-Y. Factors Influencing Retention among Regional, Rural and Remote Undergraduate Nursing Students in Australia: A Systematic Review of Current Research Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolis, M.; Clancy, C.; Hayes, R.; Sullivan-Marx, E.; Wetrich, J.G.; Broome, M. How academia can help to grow-and sustain-a robust nursing workforce. Nurs. Outlook 2023, 72, 102017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulla, M.A. Constructivism learning theory: A paradigm for students’ critical thinking, creativity, and problem solving to affect academic performance in higher education. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2172929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.; Joiner, K.; Abbasi, A. Improving students’ performance with time management skills. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2021, 18, 230–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, B.M.; Hynes, H.; Sweeney, C.; Khashan, A.S.; O’rourke, M.; Doran, K.; Harris, A.; Flynn, S.O. Medical school attrition-beyond the statistics a ten year retrospective study. BMC Med. Educ. 2013, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norfjell, O.B.; Nielsen, S.B. Men in Nursing Education: Mapping Educational Practices and Student Experiences in Iceland, Denmark, and Norway; Reform-Resource Centre for Men: Oslo, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jerez, E. Exploring the Contribution of Student Engagement Factors to Mature-Aged Students’ Persistence and Academic Achievement During the First Year of University. J. Contin. High. Educ. 2024, 72, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellizzari, M.; Billari, F. The younger, the better? Age-related differences in academic performance at university. J. Popul. Econ. 2011, 25, 697–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, M.; Portoghese, I.; Gonzales, C.I.A.; Melis, P.; Marcias, G.; Campagna, M.; Minerba, L.; Sardu, C. Lack of respect, role uncertainty and satisfaction with clinical practice among nursing students: The moderating role of supportive staff. Acta Biomed. 2017, 88, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kaphagawani, N.C.; Useh, U. Clinical Supervision and Support: Exploring Pre-registration Nursing Students’ Clinical Practice in Malawi. Ann. Glob. Health 2018, 84, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Cerra, C.; Dante, A.; Caponnetto, V.; Franconi, I.; Gaxhja, E.; Petrucci, C.; Alfes, C.M.; Lancia, L. Effects of high-fidelity simulation based on life-threatening clinical condition scenarios on learning outcomes of undergraduate and postgraduate nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamshire, C.; Jack, K.; Forsyth, R.; Langan, A.M.; Harris, W.E. The wicked problem of healthcare student attrition. Nurs. Inq. 2019, 26, e12294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, C.; Lawson, C. The problem of student attrition in higher education: An alternative perspective. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2017, 41, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Search Terms | Search Terms | Boolean Operators |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Students, Nursing/Students | |

| MeSH/CINAHL headings | undergraduate/Students, Nursing, Practical/Baccalaureate Nurses/Education, Nursing, Baccalaureate (MM “Students, Nursing”) OR (MM “Students, undergraduate Nursing”) OR (MM “Students, Nursing, Baccalaureate”) OR (MM “Students, Nursing, Practical”) OR (MM “Baccalaureate Nurses”) OR (MM “Education, Nursing, undergraduate”) | 1 OR 2 OR AND |

| Freetext keywords | Student nurs*, nurs* students, undergraduate nurs*, baccalaureate nurs* | |

| Intervention MeSH/CINAHL headings | Education, Baccalaureate/Education, Clinical/Teaching Methods, Clinical/Teaching Materials, Clinical/Practical Nursing (MM “Education, Baccalaureate”) OR (MM “Education, Clinical”) OR (MM “Teaching Methods, Clinical”) OR (MM “Teaching Materials, Clinical”) OR (MM “Practical Nursing”) | 1 OR 2 OR AND |

| Freetext keywords | Education*, program design, curricul*, teaching method, training, practic*, teach* | |

| Outcome MeSH/CINAHL headings | Students attrition/Academic failure/Academic Performance/academic achievement (MM “Student attrition”) OR (MM “Academic Failure”) OR (MM “Academic Performance”) | 1 OR 2 OR AND |

| Freetext keywords | Attrition, dropout, retention, academic failure, leave, discontinuation, withdrawal |

| Author(s), Year, Country | Study Design | Method | Aim | Sample (n) and Mean Age | Setting | Concept | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abele et al., 2013, USA [19] | Exploratory retrospective study | Students’ records | Identify courses that may predict student success in completing the baccalaureate nursing program (BNP) and examine factors associated with attrition among nursing students on academic probation. | 302 students—27.2 years | University nursing school | Attrition | Course failures Demographic characteristics (Age, gender, ethnicity, program type) |

| Ashghali Farahani et al., 2017, Iran [29] | Descriptive, qualitative | Face-to-face interviews, focus group interviews Participant observation | Elucidate the factors that lead students to drop out or express a willingness to drop out, as perceived by the students. | 19 students (intended to leave or already left the program)—23.4 years | Three BNP | Dropout Intention to leave | Attrition factors—before and after admission to the program |

| Bakker et al., 2021, The Netherlands [21] | Prospective cohort study | Baseline, second semester and one-year follow-up questionnaire, the Distress Screener, data from student administration about the dropout status | Investigate associations between psychosocial work characteristics and distress and intention to leave nursing education among third-year nursing students. | 363 third-year nursing students—24 years | BNP at a University of Applied Sciences | Intention to leave Actual dropout | Supervisor support Co-worker support Psychosocial distress Exposure to violence |

| Barbé et al., 2018, USA [35] | Descriptive, comparative | Administrative database Web-based survey The Educational Requirements Subscale | Identify demographic, academic, and social determinants associated with attrition at the end of the first semester | 164 students—24 years | Upper division BNP | Attrition | Demographic factors (Age, Gender Race/Ethnicity) Academic factors Social factors (Economic stability, Education, Social and community context, Health and health care, Neighborhood and built Environment) |

| Canzan et al., 2022, Italy [3] | Descriptive, qualitative | Semi-structured interview | Investigate the reasons behind nursing students’ attrition | 31 students—21 years | Three-year BNP | Dropout | The reasons behind drop-out Physiological causes |

| Dancot et al., 2021, Belgium [33] | Cohort study | Questionnaire at start of program and academic records at 1-year follow-up | Describe first-year nursing students’ self-esteem prior to the influence of nursing education and explore its relationship with dropout. | 464 students; Median age: 19 years | BNP | Dropout | Self-esteem Dropout |

| Kox et al., 2022, The Netherlands [22] | Prospective cohort | 10-point Likert scale Registered data | Explore the determinants of intention to leave nursing education and actual dropout from nursing education | 711 third-year students—23.5 years | Three-year BNP | Physical work factors Actual Dropout Intention to leave | Sociodemographic characteristics Physical work factors Musculoskeletal complaints at baseline Psychosocial factors |

| Kukkonen et al., 2016, Finland [27] | Descriptive, qualitative | Semi-structured interview | Describe the discontinued student in nursing education and the student’s own experiences of reasons for leaving nursing school | 25 students—31 years | Two different universities of applied sciences | Dropout | Characteristics of discontinued students The student’s own experiences of reasons for leaving nursing school |

| Matteau et al., 2023, Canada [23] | Cross-sectional correlational study | Self-administered online questionnaire, Poisson robust multivariate regression models | Explore the associations between academic conditions and (1) psychological distress and (2) intention to leave school among nursing students. | 230 nursing students (131 from Cegep, 99 from university), Cegep—22.7 years, University 29.3 years | Two nursing schools: Cegep (publicly funded college) and university (bachelor’s degree) | Intention to leave | Psychosocial stressors, Intention to leave |

| Mazzotta et al., 2024, Italy [30] | Qualitative descriptive study using thematic analysis | Face-to-face virtual interviews | Explore perceptions of nursing students and directors of Bachelor of Nursing degree courses regarding reasons for attrition among nursing students. | 12 Students—24.8 years | Bachelor of Nursing programs at one Italian university | Attrition was defined as the number of students enrolled in a nursing program who did not complete it | Identified reasons for attrition |

| Roos et al., 2016, South Africa [31] | Descriptive, quantitative | Structured telephonic interview | Determine attrition rate and factors influencing undergraduate students to discontinue their nursing studies | 54 students—21.3 years | Three South African Universities | Attrition | Attrition rates Factors leading to attrition |

| Roso-Bas et al., 2016, Spain [24] | Quantitative cross-sectional | Self-report questionnaires (TMMS-24, LOT-R, etc.) | Analyze the influence of perceived emotional intelligence, optimism, and rumination on dropout risk in nursing students | 285—third-year nursing students; mean age—not reported | BSN University | Dropout | Emotional intelligence Optimism Rumination |

| Sharif-Nia et al., 2023, Iran [25] | Cross-sectional study | Self-administered online questionnaire | Explore the relationships between experiences of bullying and intentions to drop out among Iranian nursing students, with major satisfaction and a sense of belonging serving as mediating factors. | 386 undergraduate nursing students— 22.63 years | Undergraduate nursing programs at Alborz and Mazandaran Medical Sciences Universities | Bullying behaviors, Sense of belonging, Dropout intention | Bullying and students’ intentions to drop out |

| Soerensen et al., 2023, Denmark [32] | Exploratory, qualitative | Telephone interviews | Explore the students’ experiences leading to dropping out to gain a deeper understanding of their perspectives | 15 students—ages 21–32 | University College | Dropout | Reasons for dropout |

| Ten Hoeve et al., 2017, The Netherlands [28] | Exploratory, qualitative | Semi-structured telephone interview | Examine the factors that affect student nurses’ decisions to leave or complete their program | 17 students—ages 19–33 | Four Universities of Applied Sciences | Dropout | Factors affecting student nurses’ decision to leave or complete their program |

| Van Hoek et al., 2019, Belgium [26] | Cross-sectional design | Survey | Explore the influence of socio-demographic factors, resilience, and stress-reducing activities on academic outcomes among undergraduate nursing students | 554 students—27.0 years | Six nursing colleges | Dropout Intention to leave | Intention to leave Academic success Dropout |

| Viottini et al., 2024, Italy [34] | Pilot multimethod study | Baseline quantitative online survey and follow-up semi-structured qualitative interviews | Understand the relationship between motivations for enrolment and dropout among first-year undergraduate nursing students | 759 students - median age-20, 31 students were interviewed | Five Italian universities offering Bachelor of Science in Nursing programs | Dropout | Main reasons for dropout |

| Williams, 2010, USA [36] | Qualitative | Interview | Describe common experiences and practices that helped students persist and flourish during the first part of BNP | 10 students—Mean age—not reported | College of Nursing | Attrition Persistence | Reasons affecting attrition |

| Wray et al., 2017, UK [20] | Quantitative, retrospective | The institution’s student record system | Map student characteristics at entry to the program against third-year completion data to examine non-progression and successful progression | 725 students—Mean age—not reported | Nursing school | Drop out | Successful completion Non-successful completion: Academic reasons Unsuccessful completion: non-academic reasons |

| Author/Year/Country | Academic Factors | Institutional and Social Factors | Personal Factors | Economic/ Financial Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abele et al., 2013, USA [19] | High attrition rates resulting from academic probation and course failures Poor performance in specific courses, such as psychology and microbiology | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Ashghali Farahani et al., 2017, Iran [29] | Obligation to choose nursing (cultural and legal circumstances that compelled participants to choose nursing). Lack of preparation before clinical practice. Heavy academic workload (numerous, time-consuming assignments). Academic atmosphere. Insufficient management | Improper teacher-student ratio Discrepancy between expectations and actual experiences Poor workforce management and inadequate supervision (including failure to maintain an appropriate student-teacher ratio) Shared education (nursing students feel subordinate to physicians and unable to contribute their scientific or practical knowledge in clinical settings) Negative influence from practicing nurses Low social prestige (lack of professional identity or societal recognition) | Male student (Embarrassment of working as a nurse) Lack of personal, professional identity Abuse from nurses in clinical practice | Not reported |

| Bakker et al., 2021, The Netherlands [21] | High psychological demands Supervisor and co-worker support. Psychological distress | Lack of institutional support during clinical placements Experiences of discrimination and poor social integration | Not reported | Not reported |

| Barbé et al., 2018, USA [35] | Lower confidence in study skills (note review, exam prep) Lower ability to complete reading load. | Born to immigrant families. Born outside the U.S English not spoken at home. Perceived discrimination Racial/ethnic minority status | Lower self-esteem Feelings of inadequacy Less belief in academic ability | Financial concerns Inability to purchase textbooks and required electronics. No direct association with tuition/aid |

| Canzan et al., 2022, Italy [3] | Struggles with academic workload Lack of organization and study skills Exam preparation challenges | Disparity between the ideal of nursing and the reality experienced during clinical placement Dissatisfaction with the overall clinical placement experience Perceived lack of support from the clinical instructor | Not being suited for nursing. Perception of lacking the psychological, physical and practical resources needed to cope with nursing school and profession Anxiety, emotional burden. Low motivation Mismatch between expectations and reality | Not reported |

| Dancot et al., 2021, Belgium [33] | No direct academic factor specified | Not reported | Low self-esteem (low self-liking and self-competence) | Not reported |

| Kox et al., 2022, The Netherlands [22] | Absence due to illness during the academic year. | Living situation (not residing with parents) Limited decision latitude (students with fewer opportunities to make independent work-related decisions are more likely to drop out) Support from peers and colleagues | Gender (Male sex) | Not reported |

| Kukkonen et al., 2016, Finland [27] | Satisfaction with the program Lack of studying skills Practical orientation | Negative clinical experiences No realistic job view or perception of nursing as a profession Lack of support in transitioning from high school to university Nursing does not meet students’ expectations | Wrong career choice Multiple roles (parenting, working, studying) Difficulties in combining study with one’s life situation (sickness or death of a relative) Unrealistic expectations | Not reported |

| Matteau et al., 2023, Canada [23] | Effort-reward imbalance High academic demands (efforts) | Limited support from faculty and mentors School-work–life conflict | High efforts and school-work–life conflicts Experiencing high psychological distress | Not reported |

| Mazzotta et al., 2024, Italy [30] | Poor academic preparation from high school. Insufficient study habits and skills Lack of clarity about the demands of the nursing program | Poor organization of courses and clinical placements Limited support during clinical placements. Inadequate awareness of academic support services | Unclear professional identity Emotional stress and anxiety Family-related issues | Financial obligations including tuition, transportation, living costs. Family responsibilities such as childcare or care for ill relatives |

| Roos et al., 2016, South Africa [31] | Academic non-performance | Clinical environmental difficulties Difficulty coping with university demands and clinical expectations | Illness and poor health. Personal problems. Wrong career choice | Financial reasons (Lack of financial aid) |

| Roso-Bas et al., 2016, Spain [24] | Not directly reported | Not directly reported | Pessimism Low emotional clarity/repair Depressive rumination | Not reported |

| Sharif-Nia et al., 2023, Iran [25] | Lower academic engagement | Bullying behaviors (verbal abuse, intimidation, exclusion) from faculty, classmates, and clinical instructors Negative impact of bullying on academic engagement, self-esteem, and sense of belonging | Psychological distress from bullying | Not reported |

| Soerensen et al., 2023, Denmark [32] | Feeling unprepared for challenges in clinical practice High academic workload Lack of feedback from clinical supervisors | Lack of personal and professional support in completing studies Lack of social well-being Feelings of loneliness Lacking a “sense of belonging” Social environment | Emotional vulnerability Personal experiences (e.g., illness, pregnancy) Lack of resilience | Not reported |

| Ten Hoeve et al., 2017, The Netherlands [28] | Problems with the training program Discomfort working in groups Theory–practice gap Insufficient practical skills training | Perceived lack of support from mentors and clinical team Not feeling welcomed | Personal circumstances (problems achieving learning goals, problems working in a team, uncertainty about own knowledge and abilities) | Not reported |

| Van Hoek et al., 2019, Belgium [26] | Not reported | Studying in a densely populated city | Lower resilience More destructive and less positive stress-reducing activities History of suicide attempt(s) | Not reported |

| Viottini et al., 2024, Italy [34] | Excessive academic workload Inadequate preparation for academic and clinical placement demands | Negative social image of nursing Limited career progression opportunities Negative experiences in clinical placements | Lack of interest in the nursing profession Physical demands of the profession Family, health problems, or the impossibility of balancing university and work commitments | Financial difficulties |

| Williams, 2010, USA [36] | Heavy course load during the early phase of the nursing program Difficulties with time management High academic expectations | Little or no attempt to establish bonding between the students Lack of student-teacher or peer connection. | Lack of time management skills and use of resources Academic success (poor academic performance) Lack of emotional support from family | Financial support from family |

| Wray et al., 2017, UK [20] | Students with a higher-level entry qualification | Not reported | Higher age on entry Domicile (e.g., living situation or distance from university) | Not reported |

| Author Name/Year/Country | Academic Retention Strategies | Non-Academic Retention Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Abele et al., 2013, USA [19] | Offering students the tutoring and support to succeed in the program such as additional courses designed to enhance students’ critical thinking abilities Identifying students at risk for academic failure and providing them with additional assistance prior to beginning the curriculum Meeting with the student periodically throughout the semester to provide resources and activities to help the student improve in the necessary competency areas Arranging student to student mentoring | Not reported |

| Ashghali Farahani et al., 2017, Iran [29] | Close supervision of both clinical and educational activities Providing more resources within the educational environment | Promoting awareness about the identity of nursing as a profession Efficient management of workforce provision Promoting professional sociability |

| Bakker et al., 2021, The Netherlands [21] | Co-worker support was identified as a protective factor for reducing dropout intentions Improving institutional support for students in clinical placements Addressing workplace violence to create a safer learning environment | Not reported |

| Barbé et al., 2018, The USA [35] | Individual and group tutoring (faculty-guided and peer-to-peer tutoring) Supportive networks of faculty, registered nurses, and peers from diverse backgrounds Proactive strategies to support student success, especially those targeted at diverse student populations Early intervention by nursing faculty and academic support staff to help students build confidence in their study skills Encouraging mentorship and a sense of belonging among minority and international students | Offering language support programs focused on English pronunciation, vocabulary building Offering tutoring to improve listening and note-taking skills, and verbal and nonverbal communication through role-playing scenarios Assessing students who lack access to resources and identifying creative, cost-effective ways to make resources accessible to disadvantaged students Addressing perceived discrimination and cultural mismatch |

| Canzan et al., 2022, Italy [3] | Supportive mentorships Intervention of peer leaders Creation of summer schools for future first-year students Tutorship in clinical training | Encourage potential nurses and midwives to reflect on the values, attitudes, and capabilities they need to succeed The creation of open day/week events targeting high school students, where students have the chance to attend nursing classes for several days and better understand what the main components of undergraduate nursing programs are |

| Dancot et al., 2021, Belgium [33] | Not explicitly reported | Address low self-esteem through confidence-building activities and mentoring |

| Kukkonen et al., 2016, Finland [27] | Better orientation to the academic nature of the program, especially for younger students Guidance to improve study skills | More flexible study arrangements during personal crises Improved mental health support. Early career guidance to ensure realistic expectations |

| Matteau et al., 2023, Canada [23] | Implementing structured support systems to help students manage workload and academic pressures Mental health programs to address psychological distress and overcommitment Balance between academic efforts and rewards to reduce effort-reward imbalance Institutional policies to create a more flexible academic structure Reducing school-work–life conflicts | Improve support systems to address school-work–life balance Promote social support Enhance reward structures |

| Mazzotta et al., 2024, Italy [30] | Enhance academic orientation at the beginning of the nursing program Improve clarity around nursing role expectations and academic requirements Strengthen organization of courses and clinical placements Offer targeted academic support (e.g., tutoring, skills development) | Provide emotional and psychological support to reduce stress and anxiety Facilitate financial assistance or economic support for students Improve faculty-student relationships and mentorship during clinical practice Foster social integration and professional identity through peer and faculty support |

| Roos et al., 2016, South Africa [31] | Academic assistance/clinical support | Financial assistance and wellness programs Provide career guidance and personal support systems |

| Roso-Bas et al., 2016, Spain [24] | Not reported | Develop emotional intelligence (especially clarity and repair) Promote optimism Provide psychological support services to reduce pessimism and rumination |

| Sharif-Nia et al., 2023, Iran [25] | Implement anti-bullying interventions targeting faculty and clinical instructors Support academic engagement initiatives | Foster a sense of belonging by enhancing peer relationships and support networks among students Develop interventions to prevent and respond to bullying |

| Soerensen et al., 2023, Denmark [32] | Educator involvement in guiding students through emotionally challenging learning situations Promoting learning environments that connect vulnerability with professional growth Providing structured feedback, academic guidance, and better preparation for clinical placements | More targeted efforts to improve the social environment in nursing education Fostering a sense of belonging to the nursing profession |

| Ten Hoeve et al., 2017, The Netherlands [28] | Strengthen cooperation between lecturers and mentors to ensure consistency and support throughout training Provide clear guidance and feedback from educators during both theoretical and clinical components of the program Reduce writing barriers Improve clarity of training expectations | Support students’ intrinsic motivation and career goals through meaningful engagement with the profession and role models Create a positive clinical environment where students feel welcomed, supported, and part of the team |

| Van Hoek et al., 2019, Belgium [26] | Support resilience-building among nursing students Provide academic interventions for at-risk students | Offer mental health support, particularly for students with a history of suicidal behavior Ensure adequate financial aid and social support, especially for students in urban settings |

| Viottini et al., 2024, Italy [34] | Improve preparation for study load and clinical demands Offer emotional and psychological support programs Provide flexible learning options for students with personal or work commitments | Enhance the public image of nursing through awareness campaigns Offer emotional and psychological support Increase flexibility for work-study balance |

| Williams, 2010, USA [36] | Time management skills Faculty support in building connections among students, their peers, and families Encouraging students to build a career path | Using available resources Involve families early (e.g., newsletters, introductory meetings) Foster community and belonging through student organizations and cross-level mentoring |

| Wray et al., 2017, UK [20] | Identify and support students with lower entry qualifications early Tailor academic support for younger students | Recruiting/attracting older, local students |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheikoleslami, R.L.; Princeton, D.M.; Mihaila Hansen, L.I.; Kisa, S.; Goyal, A.R. Examining Factors Associated with Attrition, Strategies for Retention Among Undergraduate Nursing Students, and Identified Research Gaps: A Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060182

Sheikoleslami RL, Princeton DM, Mihaila Hansen LI, Kisa S, Goyal AR. Examining Factors Associated with Attrition, Strategies for Retention Among Undergraduate Nursing Students, and Identified Research Gaps: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(6):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060182

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheikoleslami, Rohangez Lida, Daisy Michelle Princeton, Linda Iren Mihaila Hansen, Sezer Kisa, and Alka Rani Goyal. 2025. "Examining Factors Associated with Attrition, Strategies for Retention Among Undergraduate Nursing Students, and Identified Research Gaps: A Scoping Review" Nursing Reports 15, no. 6: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060182

APA StyleSheikoleslami, R. L., Princeton, D. M., Mihaila Hansen, L. I., Kisa, S., & Goyal, A. R. (2025). Examining Factors Associated with Attrition, Strategies for Retention Among Undergraduate Nursing Students, and Identified Research Gaps: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports, 15(6), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060182