Research Ethics Challenges, Controversies and Difficulties in Intensive Care Units—A Systematic Review of Theoretical Concepts

Abstract

1. Introduction

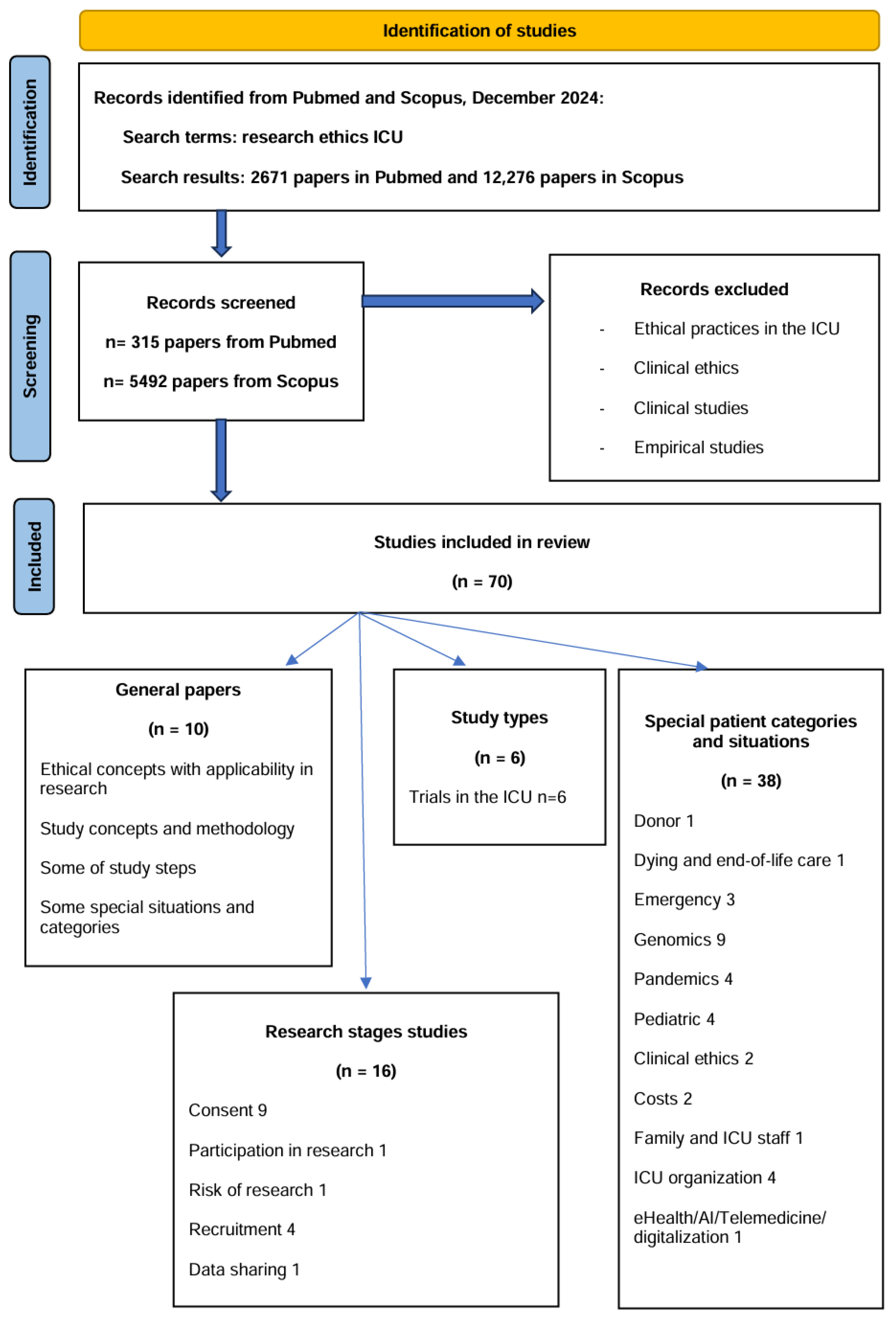

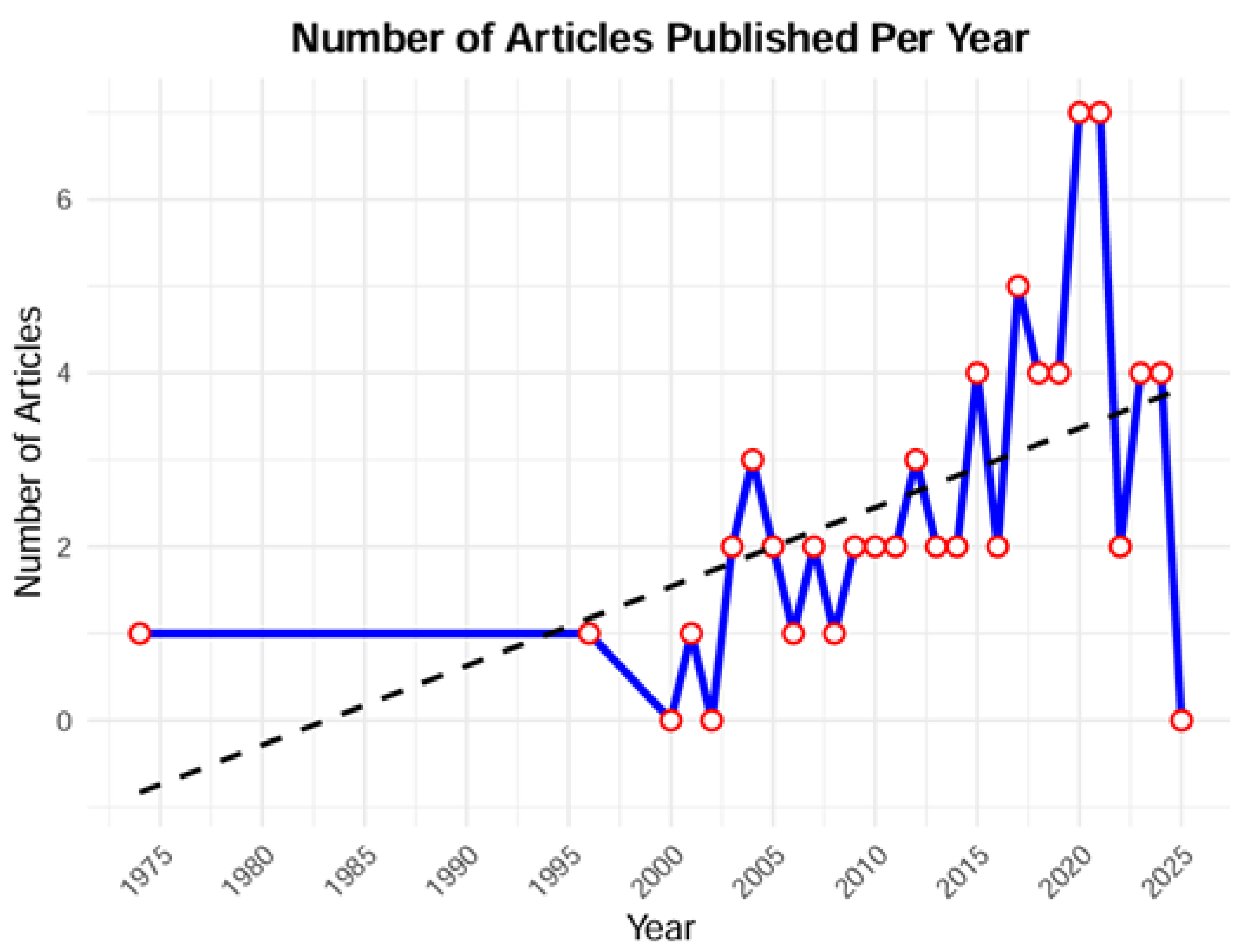

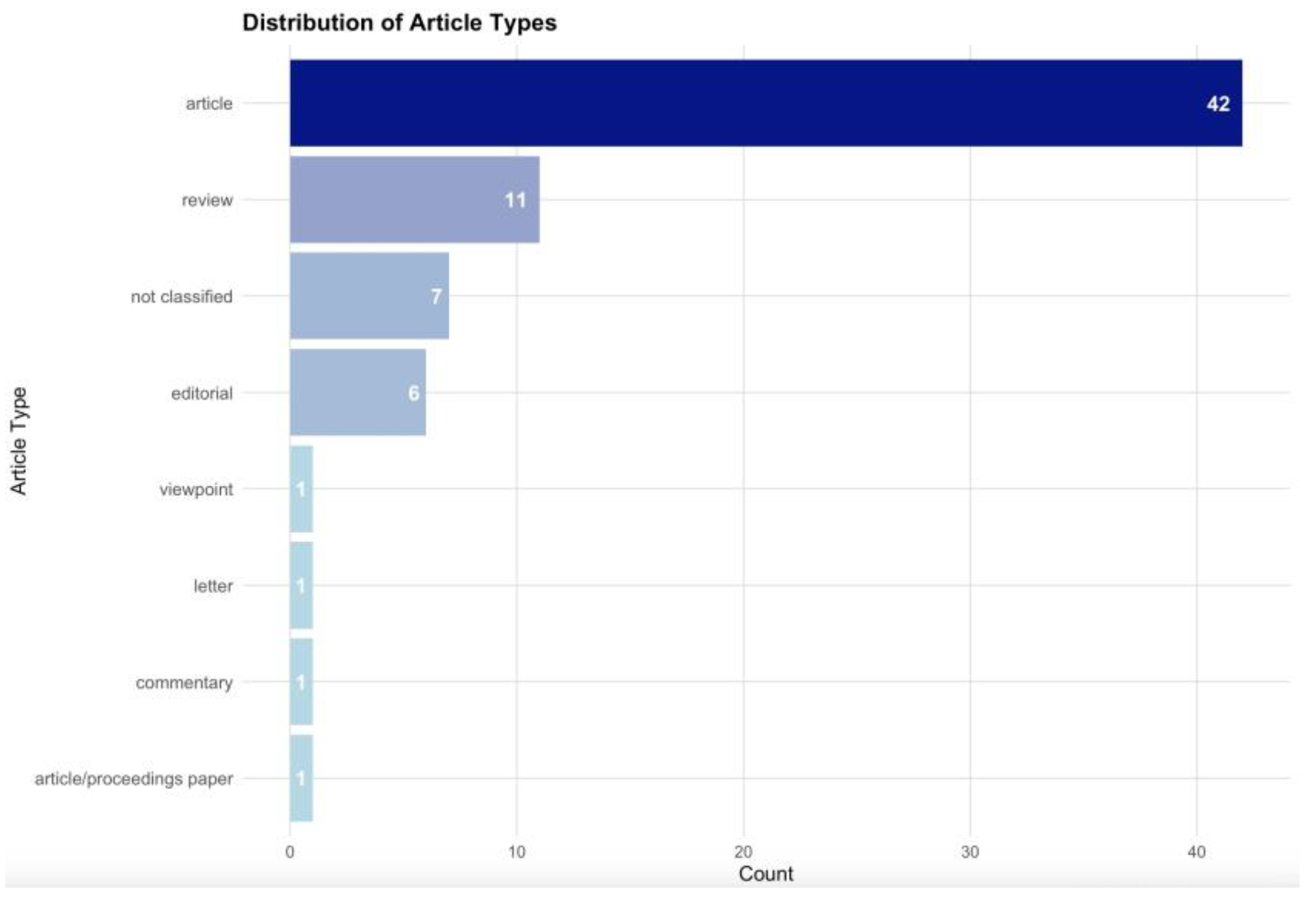

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

- I.

- What are the moral principles that govern ethical research in the ICU?

- II.

- Any research study starts from the research question, which leads to the study hypothesis. Sometimes, the primary endpoint or goal has additional secondary goals, which represent secondary information that might be gained from the study

- III.

- The clinical researcher needs knowledge on critical care, communication abilities, critical thinking when elaborating the study hypothesis, monitoring the study and analysing results, as well as knowledge of ethics and law

- IV.

- Conflicts of interest

- V.

- The oversight and approval of a research study to be conducted in the ICU is performed by the REB, the members of which also have ethical duties for the conduct of the study

- VI.

- Study registration

- VII.

- Recruitment of research subjects

- VIII.

- None should recruit patients in a study if the patient or study subject does not agree

- IX.

- Since the recruitment phase, data protection is a duty

- X.

- What type of study should the researcher choose to find the correct answer to ICU research questions?

- XI.

- Conducting RCT in the ICU generates ethical debates

- XII.

- Ethical challenges regarding ICU research publication are similar to those involving non-critical patients

- XIII.

- Special ICU populations

- The conduct of studies involving ICU staff poses ethical difficulties. ICUs are demanding, can cause doubt, anxiety, and emotional distress among healthcare professionals, leading to burnout and high turnover rates [68]. Conducting research in the ICU might be a supplementary stressful factor for clinicians.

- Pediatric ICU (PICU) research presents distinct ethical challenges. The high-stress nature of PICUs, combined with the complexity and urgency of cases, as well as the intense emotions of parents, makes obtaining meaningful informed consent particularly difficult. Therapeutic misconception, with parents feeling pressured to consent to research under such conditions and believing it to be the best option for their child [42,43], represents one of the potential difficulties. Parents’ consent and children’s assent are difficult to obtain in emergencies. Deferred consent models might allow research to proceed easier without delaying urgent care. Some authors suggest that informed consent should be ‘appropriate’ rather than ‘fully informed’ [62]. This approach remains ethically debatable, as tensions may arise when clinicians prioritise the perceived clinical benefits of rapid testing, overriding parental autonomy in decision-making [63].

- Research on organ donors and organ harvesting might be hampered by inconsistencies that exist in end-of-life practices throughout the globe, as demonstrated in the ETHICUS-II trial [80]. Controlled donation after circulatory death presents significant ethical challenges in balancing end-of-life care with organ donation.

- Research on the process of death, dying and end-of-life approaches is hampered by variability in practices. In resource-limited settings, financial constraints drive increased ICU admissions as a revenue-generating strategy, resulting in the unnecessary use of critical care resources in cases where patient-centred approaches in palliative care could provide a more ethical alternative [70]. Second, end-of-life practices are highly variable among countries [80]. Still, the inclusion of imminently dying and recently dead populations in prospective research is necessary to improve care of dying patients [55].

- XIV.

- Special ICU settings

- Research on clinical ethics is challenging as there is an overlap of research ethics and clinical ethics, starting from the fundamental ethical principles. Ethics consultations are important in the evaluation of complex ethical decisions, but from a research perspective, they come with various challenges, including methodological limitations [69].

- The integration of genomic research into neonatal and PICUs introduces significant ethical complexities. The emotional distress of family and staff is associated with genetic testing. Parent-child bonding might be influenced when early diagnosis of genetic conditions is revealed, leading to questions of when and how such information should be disclosed [40]. Accessibility to genomic testing and distributive justice in resource allocation topics arise in genomic testing [40,41].

- Emergency ICU research presents specific ethical and logistical challenges, primarily due to the urgency and complexity of critical situations [44,45]. The more severe the illness, the less time there is to conduct research, and the quicker therapeutic measures must be applied [12]. It is necessary to institute treatment immediately and not delay clinical care for research purposes. This imperative, which respects patient beneficence, leads to recruitment difficulties. Clinicians who might hesitate to use deferred consent and retrospective consent might place additional burdens on families. Extensive planning is essential to overcome logistical barriers and to ensure adherence to research protocols [45].

- Differences in ICU organisation, infrastructure, and practices create inequities, as not all ICU patients receive the same standard of care [72]. There is wide variability regarding adherence to best practices and the use of innovative therapies, leading to variations in performance [3,72]. Physicians may also rigidly adhere to standardised protocols, due to potential concerns of litigation for non-delivery, which might influence research protocol adherence [2].

- ICU costs could also be taken as research themes. Intensive care treatments place a significant financial burden on both the healthcare system and individuals, leading to accessibility and cost-effectiveness challenges [71]. ICU resource utilisation is often excessive, particularly at the end of life [70].

- Studies conducted during a pandemic should have the same methodological standards as those conducted in non-pandemic settings [13]. Healthcare services are overwhelmed, and real-time analysis is required to understand pathology, efficient treatments and outcomes. ICU research during pandemics faces ethical and logistical challenges, including delayed ethical approvals, triage, and resource allocation dilemmas. Despite the urgency of gathering data, ethics review processes create substantial delays, with an estimated delay of up to six months [65]. Therefore, timely approved protocols and rapid reviews are essential for pandemic preparedness. Inefficient global coordination of research efforts led to delayed data sharing and duplication of studies, as seen in the recent crisis, highlighting the need for improved strategies [67]. Since time is limited, there is insufficient guidance for both clinicians and researchers, exacerbating moral distress as resources are insufficient [64].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| REB | Research Ethical Board |

| RCT | Randomised controlled trial |

| PICU | Pediatric ICU |

References

- Hawryluck, L. Research ethics in the intensive care unit: Current and future challenges. Crit. Care 2004, 8, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, A.; Hammond, N.; Litton, E. Checklists and protocols in the ICU: Less variability in care or more unnecessary interventions? Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1249–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhru, R.; McWilliams, D.J.; Wiebe, D.J.; Spuhler, V.J.; Schweickert, W.D. Intensive care unit structure variation and implications for early mobilization practices. An international survey. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigatello, L.M.; George, E.; Hurford, W.E. Ethical considerations for research in critically ill patients. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 31, S178–S181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayambankadzanja, R.K.; Schell, C.O.; Gerdin Wärnberg, M.; Tamras, T.; Mollazadegan, H.; Holmberg, M. Towards definitions of critical illness and critical care using concept analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, N.; Adhikari, N.K.J.; Fowler, R.A.; Bhagwanjee, S.; Rubenfeld, G.D. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet 2010, 376, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlberg, J.; Eriksen, C.; Robertsen, A.; Beitland, S. Barriers and challenges in the process of including critically ill patients in clinical studies. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2020, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, B. Ethical considerations for critical care research. S. Afr. J. Crit. Care 2015, 31, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, H.J.; Lemaire, F. Ethics and research in critical care. Intensive Care Med. 2006, 32, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truog, R.D. Will ethical requirements bring critical care research to a halt? Intensive Care Med. 2005, 31, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Reporting Guidelines. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Committee on Ethics of the American Heart Association. Ethical Implications of Investigations in Seriously and Critically Ill Patients. Circulation 1974, 50, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Burns, K.; Finfer, S.; Kissoon, N.; Bhagwanjee, S.; Annanne, D.; Sprung, C.; Fowler, R.; Latronico, N.; Marshall, J. Clinical research ethics for critically ill patients: A pandemic proposal. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 38, e138–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estella, A. Ethics research in critically ill patients. Med. Intensiv. (Engl. Ed.) 2018, 42, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, A.M. Ethics in critical care research: Scratching the surface. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2021, 64, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Thoracic Society; Luce, J.M.; Cook, D.J.; Martin, T.R.; Angus, D.C.; Boushey, H.A.; Curtis, J.R.; Heffner, J.E.; Lanken, P.N.; Levy, M.M.; et al. The ethical conduct of clinical research involving critically ill patients in the United States and Canada: Principles and recommendations. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 170, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, R.M.G.; Møller, K.; Rossel, P.J.H. An ethical analysis of proxy and waiver of consent in critical care research. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2013, 57, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, K.E.A.; Magyarody, N.; Jiang, D.; Wald, R. Attitudes and views of the general public towards research participation. Intern. Med. J. 2013, 43, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenaud, C.; Merlani, P.; Ricou, B. Research in critically ill patients: Standards of informed consent. Crit. Care 2007, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cook, D.; Lauzier, F.; Rocha, M.G.; Sayles, M.J.; Finfer, S. Serious adverse events in academic critical care research. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2008, 178, 1181–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druml, C. Informed consent of incapable (ICU) patients in Europe: Existing laws and the EU Directive. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2004, 10, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecarnot, F.; Quenot, J.P.; Besch, G.; Piton, G. Ethical challenges involved in obtaining consent for research from patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5 (Suppl. 4), S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahafzah, R.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Khabour, O.F. The attitudes of relatives of ICU patients toward informed consent for clinical research. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2020, 1, 2760168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moodley, K.; Allwood, B.W.; Rossouw, T.M. Consent for critical care research after death from COVID-19: Arguments for a waiver. S. Afr. Med. J. 2020, 110, 629–734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paddock, K.; Woolfall, K.; Frith, L.; Watkins, M.; Gamble, C.; Welters, I.; Young, B. Strategies to enhance recruitment and consent to intensive care studies: A qualitative study with researchers and patient–public involvement contributors. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, T.S.; Ulrich, C. Ethical issues of recruitment and enrollment of critically ill and injured patients for research. AACN Adv. Crit. Care 2007, 18, 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon, F.; Lee, K. Ethical considerations in consenting critically ill patients for bedside clinical care and research. J. Intensive Care Med. 2015, 30, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, A.K.; Fish, A.F.; Cobb, J.P.; Bachman, J.A.; Jenkins, R.L.; Battistich, V.; Freeman, B.D. Surrogate consent for genomics research in intensive care. Am. J. Crit. Care 2009, 18, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoral, P.J.; Peppink, J.M.; Driessen, R.H.; Sijbrands, E.J.; Kompanje, E.J.; Kaplan, L.; Bailey, H.; Kesecioglu, J.; Cecconi, M.; Churpek, M. Sharing ICU patient data responsibly under the society of critical care medicine/European society of intensive care medicine joint data science collaboration: The Amsterdam university medical centers database (AmsterdamUMCdb) example. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, e563–e577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verceles, A.C.; Bhatti, W. The ethical concerns of seeking consent from critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients for research–a matter of possessing capacity or surrogate insight. Clin. Ethics 2018, 13, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolfall, K.; Paddock, K.; Watkins, M.; Kearney, A.; Neville, K.; Frith, L.; Welters, I.; Gamble, C.; Trinder, J.; Pattison, N.; et al. Guidance to inform research recruitment processes for studies involving critically ill patients. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2024, 25, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, B.M.; Philpott, S.; Strosberg, M.A. Protecting participants of clinical trials conducted in the intensive care unit. J. Intensive Care Med. 2011, 26, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holubkov, R.; Dean, J.M.; Berger, J.; Anand, K.J.; Carcillo, J.; Meert, K.; Zimmerman, J.; Newth, C.; Harrison, R.; Willson, D.F.; et al. Is “rescue” therapy ethical in randomized controlled trials? Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 10, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.M. Harming patients by provision of intensive care treatment: Is it right to provide time-limited trials of intensive care to patients with a low chance of survival? Med. Health Care Philos. 2021, 24, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, H. Protecting vulnerable research subjects in critical care trials: Enhancing the informed consent process and recommendations for safeguards. Ann. Intensive Care 2011, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, H.; Hull, S.C.; Sugarman, J. Variability among institutional review boards’ decisions within the context of a multicenter trial. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 29, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tao, L.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, X. Rationale and design of a prospective, multicentre, randomised, conventional treatment-controlled, parallel-group trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ulinastatin in preventing acute respiratory distress syndrome in high-risk patients. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Johnston, L. Barriers to, and facilitators of, eHealth utilisation by parents of high-risk newborn infants in the NICU: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e068759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tridente, A.; Holloway, P.A.; Hutton, P.; Gordon, A.C.; Mills, G.H.; Clarke, G.M.; Chiche, J.D.; Stuber, F.; Garrard, C.; Hinds, C.; et al. Methodological challenges in European ethics approvals for a genetic epidemiology study in critically ill patients: The GenOSept experience. BMC Med. Ethics 2019, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyngell, C.; Newson, A.J.; Wilkinson, D.; Stark, Z.; Savulescu, J. Rapid challenges: Ethics and genomic neonatal intensive care. Pediatrics 2019, 143 (Suppl. 1), S14–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, B.D.; Kennedy, C.R.; Frankel, H.L.; Clarridge, B.; Bolcic-Jankovic, D.; Iverson, E.; Shehane, E.; Celious, A.; Zehnbauer, B.A.; Buchman, T.G. Ethical considerations in the collection of genetic data from critically ill patients: What do published studies reveal about potential directions for empirical ethics research? Pharmacogenomics J. 2010, 10, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushforth, K.; Mckinney, P.A. Issues of patient consent: A study of paediatric high-dependency care. Br. J. Nurs. 2005, 14, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koogler, T. Legal and ethical policies regarding research involving critically ill children. AMA J. Ethics 2012, 14, 797–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wijk, R.P.J.; van Dijck, J.T.; Timmers, M.; van Veen, E.; Citerio, G.; Lingsma, H.F.; Maas, A.; Menon, D.; Paul, W.; Stocchetti, N.; et al. Informed consent procedures in patients with an acute inability to provide informed consent: Policy and practice in the CENTER-TBI study. J. Crit. Care 2020, 59, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, E.C.; Mann-Salinas, E.A.; Caldwell, N.W.; Chung, K.K. Challenges associated with managing a multicenter clinical trial in severe burns. J. Burn Care Res. 2020, 41, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiber, N.; Tromp, K.; Mooij, M.G.; VaN De VaTHOrST, S.; Tibboel, D.; De WilDT, S.N. Ethics of drug research in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr. Drugs 2015, 17, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deem, M.J. Whole-genome sequencing and disability in the NICU: Exploring practical and ethical challenges. Pediatrics 2016, 137 (Suppl. 1), S47–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arsov, T. “We’ve opened pandora’s box, haven’t we?” clinical geneticists’ views on ethical aspects of genomic testing in neonatal intensive care. Balk. J. Med. Genet. 2022, 25, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskell, J.; Newcombe, P.; Martin, G.; Kimble, R. Conducting a paediatric multi-centre RCT with an industry partner: Challenges and lessons learned. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2012, 48, 974–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findley, T.O.; Parchem, J.G.; Ramdaney, A.; Morton, S.U. Challenges in the clinical understanding of genetic testing in birth defects and pediatric diseases. Transl. Pediatr. 2023, 12, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.E.; Copnell, B.; Hall, H. Researching people who are bereaved: Managing risks to participants and researchers. Nurs. Ethics 2019, 26, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Dorze, M.; Barthélémy, R.; Lesieur, O.; Audibert, G.; Azais, M.A.; Carpentier, D.; Cerf, C.; Cheisson, G.; Chouquer, R.; Degos, V.; et al. Tensions between end-of-life care and organ donation in controlled donation after circulatory death: ICU healthcare professionals experiences. BMC Med. Ethics 2024, 25, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Study: Research on Dying ICU Patients Is Ethically Feasible. Available online: https://www.reliasmedia.com/articles/140792-study-research-on-dying-icu-patients-is-ethically-feasible (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Almalki, N.; Boyle, B.; O’halloran, P. What helps or hinders effective end-of-life care in adult intensive care units in Middle Eastern countries? A systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beinum, A.; Hornby, L.; Dhanani, S.; Ward, R.; Chambers-Evans, J.; Menon, K. Feasibility of conducting prospective observational research on critically ill, dying patients in the intensive care unit. J. Med. Ethics 2017, 43, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, N. The Secret House: The Ethics of Research with Imminently Dying Patients. Available online: https://blogs.bmj.com/medical-ethics/2022/06/30/the-secret-house-the-ethics-of-research-with-imminently-dying-patients/ (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Murphy, N.; Weijer, C.; Debicki, D.; Laforge, G.; Norton, L.; Gofton, T.; Slessarev, M. Ethics of non-therapeutic research on imminently dying patients in the intensive care unit. J. Med. Ethics 2023, 49, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, B.; Scales, D.C. Ethical challenges in conducting research on dying patients and those at high risk of dying. Account. Res. 2012, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.A.; Haywood, J.R.C. Critical care research on patients with advance directives or do-not-resuscitate status: Ethical challenges for clinician-investigators. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 31, S167–S171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, B.D.; Kennedy, C.R.; Bolcic-Jankovic, D.; Eastman, A.; Iverson, E.; Shehane, E.; Celious, A.; Barillas, J.; Clarridge, B. Considerations in the construction of an instrument to assess attitudes regarding critical illness gene variation research. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2012, 7, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyngell, C.; Lynch, F.; Stark, Z.; Vears, D. Consent for rapid genomic sequencing for critically ill children: Legal and ethical issues. Monash Bioeth. Rev. 2021, 39 (Suppl. 1), S117–S129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koplin, J.J.; Gyngell, C.; Savulescu, J.; Vears, D.F. Moving from ‘fully’ to ‘appropriately’ informed consent in genomics: The PROMICE framework. Bioethics 2022, 36, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poogoda, S.; Lynch, F.; Stark, Z.; Wilkinson, D.; Savulescu, J.; Vears, D.; Gyngell, C. Intensive Care Clinicians’ Perspectives on Ethical Challenges Raised by Rapid Genomic Testing in Critically Ill Infants. Children 2023, 10, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.D.; Sprung, C.L.; King, M.A.; Dichter, J.R.; Kissoon, N.; Devereaux, A.V.; Gomersall, C.D. Triage: Care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest 2014, 146, e61S–e74S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rishu, A.H.; Marinoff, N.; Julien, L.; Dumitrascu, M.; Marten, N.; Eggertson, S.; Willems, S.; Ruddell, S.; Lane, D.; Light, B.; et al. Time required to initiate outbreak and pandemic observational research. J. Crit. Care 2017, 40, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinay, R.; Baumann, H.; Biller-Andorno, N. Ethics of ICU triage during COVID-19. Br. Med. Bull. 2021, 138, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdonk, F.; Feyaerts, D.; Badenes, R.; Bastarache, J.A.; Bouglé, A.; Ely, W.; Gaudilliere, B.; Howard, C.; Kotfis, K.; Laurette, A.; et al. Upcoming and urgent challenges in critical care research based on COVID-19 pandemic experience. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2022, 41, 101121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendrick, K.; Cubbin, B. Ethics in the intensive care unit: A need for research. Nurs. Ethics 1996, 3, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schildmann, J.; Nadolny, S.; Haltaufderheide, J.; Vollmann, J.; Gysels, M.; Bausewein, C. Measuring outcomes of ethics consultation: Empirical and ethical challenges. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 47, e67–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, N.; Brumback, L.C.; Halpern, S.D.; Coe, N.B.; Brumback, B.; Curtis, J.R. Evaluating the economic impact of palliative and end-of-life care interventions on intensive care unit utilization and costs from the hospital and healthcare system perspective. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 1314–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinja, S.; Bahuguna, P.; Duseja, A.; Kaur, M.; Chawla, Y.K. Cost of intensive care treatment for liver disorders at tertiary care level in India. PharmacoEconomics-Open 2018, 2, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, H.; Jopling, J.K.; Scott, J.Y.; Ramsey, M.; Vranas, K.; Wagner, T.H.; Milstein, A. Detecting organisational innovations leading to improved ICU outcomes: A protocol for a double-blinded national positive deviance study of critical care delivery. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronstad, O.; Flaws, D.; Fraser, J.F.; Patterson, S. The intensive care unit environment from the perspective of medical, allied health and nursing clinicians: A qualitative study to inform design of the ‘ideal’ bedspace. Aust. Crit. Care 2021, 34, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Y. Ethical issues in the critically ill patient. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2001, 7, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, T.L.; Childress, J.F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; ISBN 0195143310. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, K.; Moore, A.; Hickling, K. Critical care research ethics: Making a case for non-consensual research in ICU. Crit. Care Resusc. 2004, 6, 218–625. [Google Scholar]

- Krewulak, K.; Ogunyannwo, T.; Martin, D.A.; Ruddell, S.; Yasmeen, I.; Fiest, K. ICU Care Team’s Perception of Clinical Research in the ICU: A Cross-Sectional Study. Crit. Care Explor. 2024, 6, e1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppolino, M.; Ackerson, L. Do surrogate decision makers provide accurate consent for intensive care research? Chest 2001, 119, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CONSORT Statement: Updated Guideline for Reporting Randomised Trials. Available online: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/consort/ (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Avidan, A.; Sprung, C.L.; Schefold, J.C.; Ricou, B.; Hartog, C.S.; Nates, J.L.; Jaschinski, U.; Lobo, S.; Joynt, G.M.; Lesieur, O.; et al. Variations in end-of-life practices in intensive care units worldwide (Ethicus-2): A prospective observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification of Domains | Ethical Challenge/ Controversy/Difficulty | References |

|---|---|---|

| I. Research ethical principles | Autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice | [1,4,8,9,14,16] |

| II. Study idea/ hypothesis |

| [1,4,9,12,14,15,17] |

| Social value: the study is designed for the benefit of the community, but not of the individual research subject | [1,4,9,12,14,15,17] | |

| Results should be generalisable | [8] | |

| Clinical equipoise | [8,9,10,16,27] | |

| Safety and efficacy tested in a low number of patients | [4] | |

| Balance between benefits and harms, favourable risk-benefit ratio | [1,4,7,8,9,10,12,13,14,15,16,17,24,34] | |

| Protection from harm: low or minimal risk studies, reasonable risk, safeguards against anticipated risks | [4,9,10,12,13,16,20,32,35] | |

| Lack of guidelines for ethical conduct of research in the critically ill | [4] | |

| Restrictive regulations | [4] | |

| The quality of the study is a duty and respect for the research subject | [4] | |

| Scientific validity: enrollment criteria fit with the scientific goals and outcome measures reflect the purpose of the study, correct study design and protocol, sound research project | [8,15,16] | |

| Liability in case of harm | [1,12] | |

| III. Researcher | Critical thinking, knowledge of ethics and law | [1,8,10,12] |

| [8,12,16,22] | |

| IV. Conflicts | Conflicts of interest in the team: physician versus researcher, among physicians | [8,12,16,22,32] |

| Logistics: the study should be performed without placing extra burdens on the clinical team | [1,38] | |

| Financial conflict of interest and funding: Industry involvement High costs for ICU care, high costs for research | [1,9,16] | |

| Researcher conflict of interest: promotion, fame, prestige | [4,14,16] | |

| V. Research ethics board | Standard requirements for protocol approval Independent review of the protocol | [1,7,8,9,12,14,16,27,36,39] |

| Expert consultants who understand the problems very well | [16] | |

| VI. Study registration | Before commencement | [16] |

| VII. Patient recruitment/ enrollment | Justice:

| [7,8,9,16,40,41] |

| Therapeutic misconception: patients or surrogates want to benefit from research and feel obliged to enrol | [16,22,32,42,43] | |

| VIII. Consent (informed, voluntary, autonomous, valid) | Patients’ characteristics: cognitively impaired, captive, dependent on care | [1,4,8,9,12,16,30,44,45] |

| Analysis: lack of decisional capacity, too ill to understand | [4,9,12,13,14,17,22,24,26,35] | |

| Protection: vulnerable population, with high mortality and morbidity, unable to tolerate supplementary risks | [1,4,8,9,12,14,16,32,34,35,46] | |

| Respect for autonomy | [4,7,8,9,10,14,15] | |

| Best interest of the patient | [9,21] | |

Alternative methods of consent: surrogate or proxy consent

| [4,7,8,9,12,13,14,17,22,23,25,26,27,28,35,36,43,47,48] | |

| Alternative consent methods: retrospective, deferred or delayed consent, waiver of consent, prospective (advanced planning) consent | [4,13,16,22,24,27,44,49] | |

| Providing information (and the quality of the information) about the study to the research subjects | [18,19,31] | |

| Able to withdraw from the study | [8,12] | |

| Documentation of consent | [12] | |

| IX. Confidentiality | Personal data and biological samples protection | [14,15,16,29,42,50] |

| X. Observational studies | Registries, audits, prospective or retrospective (e.g., observational cohort, case-control studies) | [12,13,16] |

| XI. Interventional studies |

| [9,12,13,16,27,32,37] |

| Control group: standard of care? (Broad variations in practice) | [4,9,13,14,16] | |

| Minimisation of risk, minimal risk, no more than minor increase above risk, “rescue” therapy trials | [10,33] | |

| XII. Publication | Dissemination of study results is mandatory | [1,14,16] |

| Peer reviewers and editors must recognise conflicts of interest | [16] | |

| XIII. Special populations | Pediatric | [12,16,40,42,43,46] |

| Staff and families | [15,51] | |

| Donor | [52] | |

| The dying patient | [4,53,54,55,56,57,58,59] | |

| XIV. Special settings | Emergency (cardiac arrest, traumatic injuries, myocardial infarction, arrythmias, stroke) | [4,9,12,14,44,45,49] |

| Genomic | [39,41,47,48,50,60,61,62,63] | |

| Pandemics | [13,64,65,66,67] | |

| E-health | [38] | |

| Clinical ethics | [68,69] | |

| Costs | [70,71] | |

| ICU organisation | [2,3,72,73] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrișor, C.; Chirteș, M.; Magdaș, T.; Szabo, R.; Constantinescu, C.; Crișan, H.T. Research Ethics Challenges, Controversies and Difficulties in Intensive Care Units—A Systematic Review of Theoretical Concepts. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050164

Petrișor C, Chirteș M, Magdaș T, Szabo R, Constantinescu C, Crișan HT. Research Ethics Challenges, Controversies and Difficulties in Intensive Care Units—A Systematic Review of Theoretical Concepts. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(5):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050164

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrișor, Cristina, Mara Chirteș, Tudor Magdaș, Robert Szabo, Cătălin Constantinescu, and Horațiu Traian Crișan. 2025. "Research Ethics Challenges, Controversies and Difficulties in Intensive Care Units—A Systematic Review of Theoretical Concepts" Nursing Reports 15, no. 5: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050164

APA StylePetrișor, C., Chirteș, M., Magdaș, T., Szabo, R., Constantinescu, C., & Crișan, H. T. (2025). Research Ethics Challenges, Controversies and Difficulties in Intensive Care Units—A Systematic Review of Theoretical Concepts. Nursing Reports, 15(5), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050164