Suitability of a Low-Fidelity and Low-Cost Simulator for Teaching Basic Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation—“Hands-Only CPR”—To Nursing Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

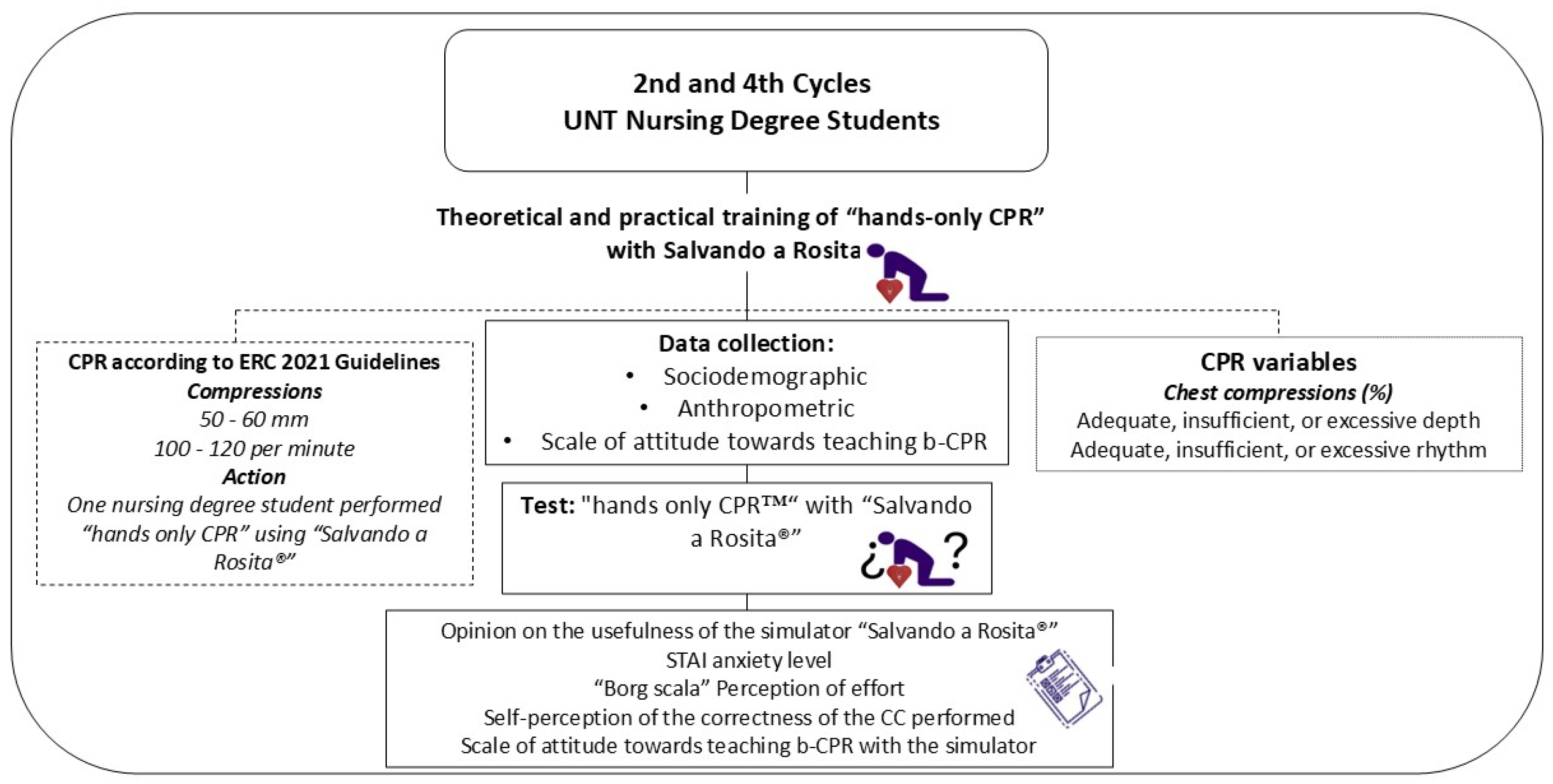

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

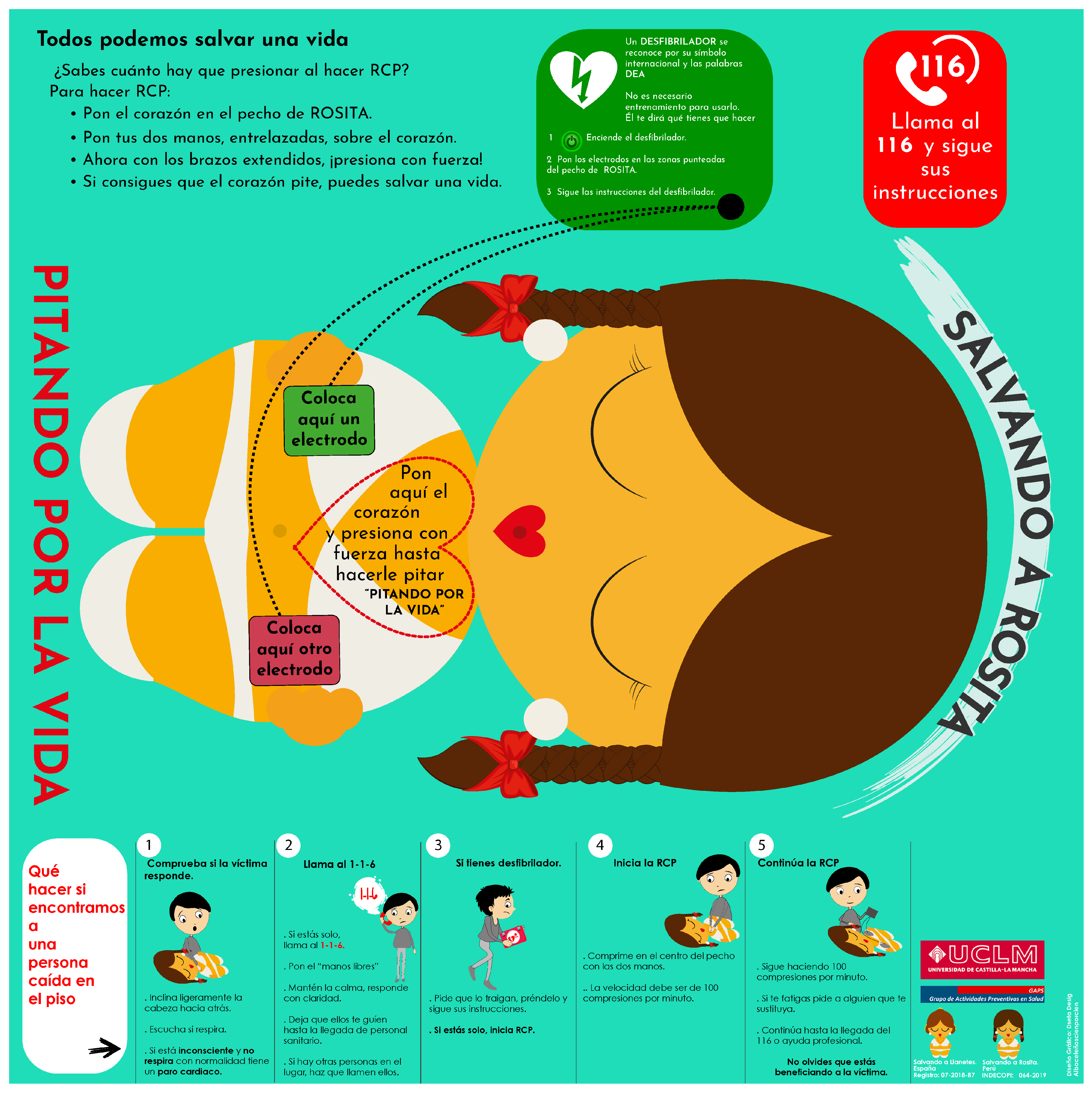

2.2. Procedures and Instruments

Intervention

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| BLS | Basic life support |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CC | Chest compression |

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| ERC | European Resuscitation Council |

| OHCA | Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest |

| RPE | Rating of perceived exertion |

| STAI | State–trait anxiety inventory |

| STAI-SA | State anxiety |

| STAI-TA | Trait anxiety |

| UNT | National University of Trujillo |

References

- Gräsner, J.-T.; Herlitz, J.; Tjelmeland, I.B.; Wnent, J.; Masterson, S.; Lilja, G.; Bein, B.; Böttiger, B.W.; Rosell-Ortiz, F.; Nolan, J.P.; et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Epidemiology of cardiac arrest in Europe. Resuscitation 2021, 161, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandroni, C.; D’Arrigo, S.; Cacciola, S.; Hoedemaekers, C.W.E.; Kamps, M.J.A.; Oddo, M.; Taccone, F.S.; Di Rocco, A.; Meijer, F.J.A.; Westhall, E.; et al. Prediction of poor neurological outcome in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest: A systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1803–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosajee, U.S.; Saleem, S.G.; Iftikhar, S.; Samad, L. Outcomes following cardiopulmonary resuscitation in an emergency department of a low- and middle-income country. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juul Grabmayr, A.; Folke, F.; Samsoee Kjoelbye, J.; Andelius, L.; Krammel, M.; Ettl, F.; Sulzgruber, P.; Krychtiuk, K.A.; Sasson, C.; Stieglis, R.; et al. Incidence and Survival of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in Public Housing Areas in 3 European Capitals. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2024, 17, e010820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amacher, S.A.; Bohren, C.; Blatter, R.; Becker, C.; Beck, K.; Mueller, J.; Loretz, N.; Gross, S.; Tisljar, K.; Sutter, R.; et al. Long-term Survival After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2022, 7, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyckoff, M.H.; Singletary, E.M.; Soar, J.; Olasveengen, T.M.; Greif, R.; Liley, H.G.; Zideman, D.; Bhanji, F.; Andersen, L.W.; Avis, S.R.; et al. 2021 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations: Summary From the Basic Life Support; Advanced Life Support; Neonatal Life Support; Education, Implementation, and Teams; First Aid Task Forces; and the COVID-19 Working Group. Resuscitation 2021, 169, 229–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Jeong, W.J.; Moon, H.J.; Kim, G.W.; Cho, J.S.; Lee, K.M.; Choi, H.J.; Park, Y.J.; Lee, C.A. Factors associated with high quality observer-performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Emerg. Med. Int. 2020, 2020, 8356201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkun, A.; Gautam, A.; Trunkwala, F. Global prevalence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training among the general public: A scoping review. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2021, 8, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, X.M.A.; Liao, W.A.; Wang, W.; Seah, B. Effectiveness of technology-based CPR training on adolescent skills and knowledge: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e36423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.S.; Kim, S.R.; Cho, B.J. The Effect of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) Education on the CPR Knowledge, Attitudes, Self-Efficacy, and Confidence in Performing CPR among Elementary School Students in Korea. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Salvado, V.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, E.; Abelairas-Gómez, C.; Ruano-Raviña, A.; Peña-Gil, C.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Rodriguez-Nunez, A. Training adult laypeople in basic resuscitation procedures. A systematic review. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2020, 73, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooker, E.A.; Werft, M. Using laypersons to train friends and family in Hands-Only CPR improves their willingness to perform bystander CPR. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 49, 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaskiewicz, F.; Timler, D. Attitudes of Asian and Polish Adolescents towards the Use of Ecological Innovations in CPR Training. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Agra, M.; Rey-Fernández, L.; Pacheco-Rodríguez, D.; Fernández-Méndez, F.; Barcala-Furelos, R.; Greif, R. Paediatric manikins and school nurses as Basic Life Support coordinators: A useful strategy for schools? Health Educ. J. 2023, 82, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfai, B.; Pek, E.; Pandur, A.; Csonka, H.; Betlehem, J. ‘The year of first aid’: Effectiveness of a 3-day first aid programme for 7–14-year-old primary school children. Emerg. Med. J. 2017, 34, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto-Pino, L.; Isasi, S.M.; Agra, M.O.; Van Duijn, T.; Rico-Díaz, J.; Núñez, A.R.; Furelos, R.B. Assessing the quality of chest compressions with a DIY low-cost manikin (LoCoMan) versus a standard manikin: A quasi-experimental study in primary education. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 3337–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Duijn, T.; Sabrah, N.Y.A.; Pellegrino, J.L. Do-It-Yourself Devices for Training CPR in Laypeople: A Scoping Review. Int. J. First Aid Educ. 2024, 7, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapigliati, A.; Zace, D.; Matsuyama, T.; Pisapia, L.; Saviani, M.; Semeraro, F.; Ristagno, G.; Laurenti, P.; Bray, J.E.; Greif, R. Community Initiatives to Promote Basic Life Support Implementation-A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.; Acworth, J.; Page, G.; Parr, M.; Morley, P. Australian Resuscitation Council and KIDS SAVE LIVES stakeholder organisations. Aussie KIDS SAVE LIVES: An Australian Resuscitation Council position statement supported by stakeholders. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2021, 33, 944–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabanales-Sotos, J.; Guisado-Requena, I.M.; Leiton-Espinoza, Z.E.; Guerrero-Agenjo, C.M.; López-Torres-Hidalgo, J.; Martín-Conty, J.L.; Martín-Rodriguez, F.; López-Tendero, J.; López-González, A. Development and validation of a new ultra-compact and cost-effective device for basic manual CPR training: A Randomized, Sham-Controlled, Blinded Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbina, Y.E.; Leiton, Z.E.; LópezGonzález, A.; Rabanales-Sotos, J.; Silva, A.R.F.; Fhon, J.R.S. Development and semantic validation of an instrument for the assessment of knowledge and attitudes towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adolescents. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2022, 40, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruíz, R.; Valderrama-Espejo, O. El método de los cuatro pasos: Narrativas que recuperan su historia. Rev. Rutas Form. Práct. Exp. 2017, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight in Adults. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: Executive summary. Am. J. Clin. 1998, 68, 899–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcala-Furelos, R.; Abelairas-Gomez, C.; Palacios-Aguilar, J.; Rey, E.; Costas-Veiga, J.; Lopez-Garcia, S.; Rodriguez-Nunez, A. Can surf-lifeguards perform a quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation sailing on a lifeboat? A quasi-experimental study. Emerg. Med. J. 2017, 34, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobase, L.; Cardoso, S.H.; Rodrigues, R.T.F.; Souza, D.R.D.; Gugelmin-Almeida, D.; Polastri, T.F.; Peres, H.H.C.; Timerman, S. The application of Borg scale in cardiopulmonary resuscitation: An integrative review. PLoS Digit. Health 2024, 3, e0000592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Paino, M.; Sierra-Baigrie, S.; Lemos-Giráldez, S.; Muñiz, J. Propiedades psicométricas del “Cuestionario de Ansiedad Estado-Rasgo” (STAI) en Universitarios. Behav. Psychol. 2012, 20, 547–561. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Maestre-Miquel, C.; Martín-Rodríguez, F.; Durantez-Fernández, C.; Martín-Conty, J.L.; Viñuela, A.; Polonio-López, B.; Romo-Barrientos, C.; Criado-Álvarez, J.J.; Torres-Falguera, F.; Conty-Serrano, R.; et al. Gender Differences in Anxiety, Attitudes, and Fear among Nursing Undergraduates Coping with CPR Training with PPE Kit for COVID. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Conty, J.L.; Martin-Rodríguez, F.; Criado-Álvarez, J.J.; Romo Barrientos, C.; Maestre-Miquel, C.; Viñuela, A.; Polonio-López, B.; Durantez-Fernández, C.; Marcos-Tejedor, F.; Mohedano-Moriano, A. Do Rescuers’ Physiological Responses and Anxiety Influence Quality Resuscitation under Extreme Temperatures? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowbridge, C.; Parekh, J.N.; Ricard, M.D.; Potts, J.; Patrickson, W.C.; Cason, C.L. A randomized cross-over study of the quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among females performing 30:2 and hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation. BMC Nurs. 2009, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera, S.; González, B.; Alvarez, J.; Fernández, M.M.; Saura, J.M. The physiological effect on rescuers of doing 2 min of uninterrupted chest compressions. Resuscitation 2007, 74, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taussig, H.B. “Death” from lightning--and the possibility of living again. Ann. Intern. Med. 1968, 68, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Martínez, M.; Herrería-Bustillo, V.J. Evaluation of compressor fatigue at 150 compressions per minute during cardiopulmonary resuscitation using a large dog manikin. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2023, 33, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abelairas-Gómez, C.; Schroeder, D.C.; Carballo-Fazanes, A.; Böttiger, B.W.; López-García, S.; Martínez-Isasi, S.; Rodríguez-Núñez, A. KIDS SAVE LIVES in schools: Cross-sectional survey of schoolteachers. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021, 180, 2213–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.L.; Li, L.; Jiang, C.; Xu, B.; Wang, H.L.; Xiong, D.; Sheng, L.P.; Yang, Q.S.; Jiang, S.; Xu, P.; et al. Up-down hand position switch may delay the fatigue of non-dominant hand position rescuers and improve chest compression quality during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A randomized crossover manikin study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rössler, B.; Goschin, J.; Maleczek, M.; Piringer, F.; Thell, R.; Mittlböck, M.; Schebesta, K. Providing the best chest compression quality: Standard CPR versus chest compressions only in a bystander resuscitation model. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.G.; Neumann, P.; Reinhardt, S.; Timmermann, A.; Niklas, A.; Quintel, M.; Eich, C.B. Impact of physical fitness and biometric data on the quality of external chest compression: A randomised, crossover trial. BMC Emerg. Med. 2011, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, T.M.; Kloppe, C.; Hanefeld, C. Basic life support skills of high school students before and after cardiopulmonary resuscitation training: A longitudinal investigation. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2012, 20, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebersold, M. Simulation-Based Learning: No Longer a Novelty in Undergraduate Education. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2018, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.; Gomar, C.; Rodriguez, E.; Trapero, M.; Gallart, A. Cost minimization analysis for basic life support. Resuscitation 2019, 134, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasson, C.; Haukoos, J.S.; Bond, C.; Rabe, M.; Colbert, S.H.; King, R.; Sayre, M.; Heisler, M. Barriers and facilitators to learning and performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation in neighborhoods with low bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation prevalence and high rates of cardiac arrest in Columbus, OH. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2013, 6, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, N.J.; Glavin, R.J. Simulación de baja a alta fidelidad: ¿un continuo de la educación médica? Med. Educ. 2003, 37, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 89) | Males (n = 13) | Females (n = 76) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20.7 ± 1.88) | 20.2 ± 1.88 | 20.8 ± 1.57 | 0.868 |

| Weight (kg) | 61.89 ± 11.25 | 72.45 ± 11.55 | 60.08 ± 10.23 | 0.386 |

| Height (m) | 157.3 ± 0.068 | 166.6 ± 0.055 | 155.7 (0.057) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.94 ± 10.62 | 26.02 ± 3.40 | 24.76 (3.80) | 0.267 |

| Weight status (%) | ||||

| Normal weight | 59.6 | 38.5 | 63.2 | <0.001 |

| Overweight/obesity | 40.4 | 61.5 | 36.8 | <0.001 |

| Variables | Total (n = 89) | Males (n = 13) | Females (n = 76) | p-Value for Males vs. Females |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait Anxiety (TA) | 17.30 ± 4.56 | 17.00 ± 5.38 | 17.00 ± 4.45 | 0.825 |

| State Anxiety (SA) | 37.00 ± 4.50 | 33.46 ± 4.53 | 37.60 ± 4.23 | 0.002 |

| Total (n = 89) | Males (n = 13) | Females (n = 76) | p-Value for Males vs. Females | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borg rating | 14.43 ± 1.71 | 13.62 ± 1.71 | 14.57 ± 1.68 | <0.001 |

| Light | 19.1 | 46.15 | 14.48 | <0.001 |

| Somewhat hard | 44.9 | 23.08 | 48.68 | <0.001 |

| Hard | 28.1 | 30.77 | 27.63 | <0.001 |

| Very hard | 7.9 | 0 | 9.21 | <0.001 |

| Total (n = 89) | Males (n = 13) | Females (n = 76) | p-Value for Males vs. Females | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compression rate (CC/min) | 125.7 ± 21.92 | 131.2 ± 18.95 | 124 ± 22.33 | 0.281 |

| Correct compression depth (%) | 89.6 ± 18.708 | 91.4 ± 11.55 | 87.9 ± 18.67 | 0.535 |

| Normal weight | 34.20 ± 29.04 | |||

| Overweight/obesity | 70.92 ± 25.29 | |||

| p-value | <0.001 | |||

| Verify security of the environment | 67.4 ± 0.471 | 53.8 ± 0.519 | 69.74 ± 0.462 | 0.338 |

| Check consciousness | 98.9 ± 0.106 | 100 ± 0.001 | 98.68 ± 0.115 | 1 |

| Call emergency services | 82 ± 0.386 | 92.31 ± 0.277 | 80.26 ± 0.401 | 0.449 |

| Use correct hand position | 85.4 ± 0.355 | 69.2 ± 0.376 | 64.47 ± 0.354 | 1 |

| Use correct rescuer position | 65.2 ± 0.479 | 84.62 ± 0.480 | 85.53 ± 0.482 | 1 |

| Use adequate rate of CCs | 38.2 ± 0.489 | 53.85 ± 0.519 | 35.53 ± 0.482 | 0.231 |

| CPR Pre-Training | CPR Post-Training | Total p-Value for Pre- vs. Post-Training | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 89) | Males (n = 13) | Females (n = 76) | p-Value | Total (n = 89) | Males (n = 13) | Females (n = 76) | p-Value | |||

| React and act to a person who does not respond | Very capable | 40.4 | 38.5 | 40.8 | 0.320 | 58.4 | 76.9 | 55.3 | 0.324 | 0.071 |

| Somewhat capable | 48.3 | 61.5 | 46.1 | 39.3 | 23.1 | 42.1 | ||||

| Not very capable | 11.2 | 0 | 13.2 | 2.2 | 0 | 2.6 | ||||

| Alert emergency services quickly | Very capable | 69.7 | 76.9 | 68.4 | 0.743 | 77.5 | 84.6 | 76.3 | 0.697 | 0.023 |

| Somewhat capable | 28.2 | 23.1 | 28.9 | 19.1 | 15.4 | 19.7 | ||||

| Not very capable | 2.2 | 0 | 2.6 | 23.07 | 0 | 3.9 | ||||

| Report details to the telephone operator of the emergency system | Very capable | 57.3 | 53.8 | 57.9 | 0.645 | 69.7 | 92.3 | 65.8 | 0.155 | 0.545 |

| Somewhat capable | 39.3 | 34.5 | 39.5 | 27 | 7.7 | 30.3 | ||||

| Not very capable | 3.4 | 7.7 | 2.6 | 23.07 | 0 | 3. | ||||

| Assess whether a person is unconscious | Very capable | 49.4 | 23.1 | 53.9 | 0.080 | 85.4 | 92.3 | 84.2 | 0.681 | 0.639 |

| Somewhat capable | 48.3 | 76.9 | 43.4 | 11.2 | 7.7 | 11.8 | ||||

| Not very capable | 2.2 | 0 | 2.63 | 23.07 | 0 | 3.9 | ||||

| Recognize cardiac arrest | Very capable | 22.5 | 15.4 | 23.7 | 0.777 | 47.2 | 53.8 | 46.1 | 0.274 | 0.296 |

| Somewhat capable | 53.9 | 61.5 | 52.6 | 50.6 | 34.5 | 52.6 | ||||

| Not very capable | 23.6 | 23.1 | 23.7 | 2.2 | 7.7 | 1.3 | ||||

| Make decisions when faced with a person in cardiac arrest | Very capable | 30.3 | 30.8 | 30.3 | 0.785 | 56.2 | 69.2 | 53.9 | 0.305 | 0.984 |

| Somewhat capable | 47.2 | 53.8 | 46.1 | 43.8 | 30.8 | 46.1 | ||||

| Not very capable | 22.5 | 15.4 | 23.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Stay calm when faced with a person in cardiac arrest | Very capable | 48.3 | 61.5 | 40.8 | 0.288 | 64 | 92.3 | 59.2 | 0.70 | 0.011 |

| Somewhat capable | 49.4 | 38.5 | 51.3 | 32.6 | 7.7 | 36.8 | ||||

| Not very capable | 6.7 | 0 | 7.9 | 23.07 | 0 | 3.9 | ||||

| Apply the CPR sequence automatically | Very capable | 33.3 | 23.1 | 35.5 | 0.650 | 60.7 | 69.2 | 59.2 | 0.667 | 0.045 |

| Somewhat capable | 37.1 | 46.2 | 35.5 | 36 | 30.8 | 36.8 | ||||

| Not very capable | 29.2 | 30.8 | 28.9 | 23.07 | 0 | 3.9 | ||||

| Indicate the need to open the airway in an unconscious person | Very capable | 21.3 | 53.8 | 52.6 | 0.341 | 80.9 | 76.9 | 81.6 | 0.481 | 0.140 |

| Somewhat capable | 39.3 | 38.5 | 40.8 | 14.6 | 23.1 | 13.2 | ||||

| Not very capable | 39.3 | 7.7 | 6.6 | 4.5 | 0 | 5.3 | ||||

| Indicate the need to assess whether an unconscious person is breathing | Very capable | 52.8 | 53.85 | 52.63 | 0.981 | 88.8 | 100 | 86.8 | 0.382 | 0.086 |

| Somewhat capable | 40.4 | 34.46 | 40.79 | 7.9 | 0 | 9.2 | ||||

| Not very capable | 6.7 | 7.69 | 6.58 | 3.4 | 0 | 3.9 | ||||

| Perform CCs | Very capable | 39.3 | 38.5 | 39.5 | 0.716 | 52.8 | 69.2 | 50 | 0.374 | 0.049 |

| Somewhat capable | 44.9 | 38.5 | 46.1 | 42.7 | 30.8 | 44.7 | ||||

| Not very capable | 15.7 | 23.1 | 14.5 | 4.5 | 0 | 5.3 | ||||

| Perform CPR on an adult | Very capable | 36 | 30.8 | 36.8 | 0.856 | 44.9 | 69.2 | 40.8 | 0.140 | 0.229 |

| Somewhat capable | 39.3 | 46.2 | 38.2 | 49.4 | 30.8 | 52.6 | ||||

| Not very capable | 24.7 | 23.1 | 25 | 5.6 | 0 | 6.6 | ||||

| Inform the emergency responders of what has been performed prior to their arrival | Very capable | 58.4 | 46.2 | 60.5 | 0.181 | 83.1 | 92.3 | 81.6 | 0.622 | 0.174 |

| Somewhat capable | 33.7 | 53.8 | 30.3 | 15.7 | 7.7 | 17.1 | ||||

| Not very capable | 7.9 | 0 | 9.2 | 1.1 | 0 | 1.3 | ||||

| Total (n = 89) | Males (n = 13) | Females (n = 76) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-perception of having performed the compressions correctly | 44.9 | 69.2 | 40.8 | 0.057 |

| Belief that the simulator is useful for teaching BLS to first-year nursing students | 97.8 | 100 | 97.4 | 0.554 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leiton-Espinoza, Z.E.; López-González, Á.; Villanueva-Benites, M.E.; Urbina-Rojas, Y.E.; Rabanales-Sotos, J.; Hoyos-Álvarez, Y.; Gómez-Lujan, M.D.P. Suitability of a Low-Fidelity and Low-Cost Simulator for Teaching Basic Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation—“Hands-Only CPR”—To Nursing Students. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050162

Leiton-Espinoza ZE, López-González Á, Villanueva-Benites ME, Urbina-Rojas YE, Rabanales-Sotos J, Hoyos-Álvarez Y, Gómez-Lujan MDP. Suitability of a Low-Fidelity and Low-Cost Simulator for Teaching Basic Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation—“Hands-Only CPR”—To Nursing Students. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(5):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050162

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeiton-Espinoza, Zoila Esperanza, Ángel López-González, Maritza Evangelina Villanueva-Benites, Yrene E. Urbina-Rojas, Joseba Rabanales-Sotos, Yda Hoyos-Álvarez, and María D. Pilar Gómez-Lujan. 2025. "Suitability of a Low-Fidelity and Low-Cost Simulator for Teaching Basic Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation—“Hands-Only CPR”—To Nursing Students" Nursing Reports 15, no. 5: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050162

APA StyleLeiton-Espinoza, Z. E., López-González, Á., Villanueva-Benites, M. E., Urbina-Rojas, Y. E., Rabanales-Sotos, J., Hoyos-Álvarez, Y., & Gómez-Lujan, M. D. P. (2025). Suitability of a Low-Fidelity and Low-Cost Simulator for Teaching Basic Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation—“Hands-Only CPR”—To Nursing Students. Nursing Reports, 15(5), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050162