How Does Professional Habitus Impact Nursing Autonomy? A Hermeneutic Qualitative Study Using Bourdieu’s Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Analytical Approach

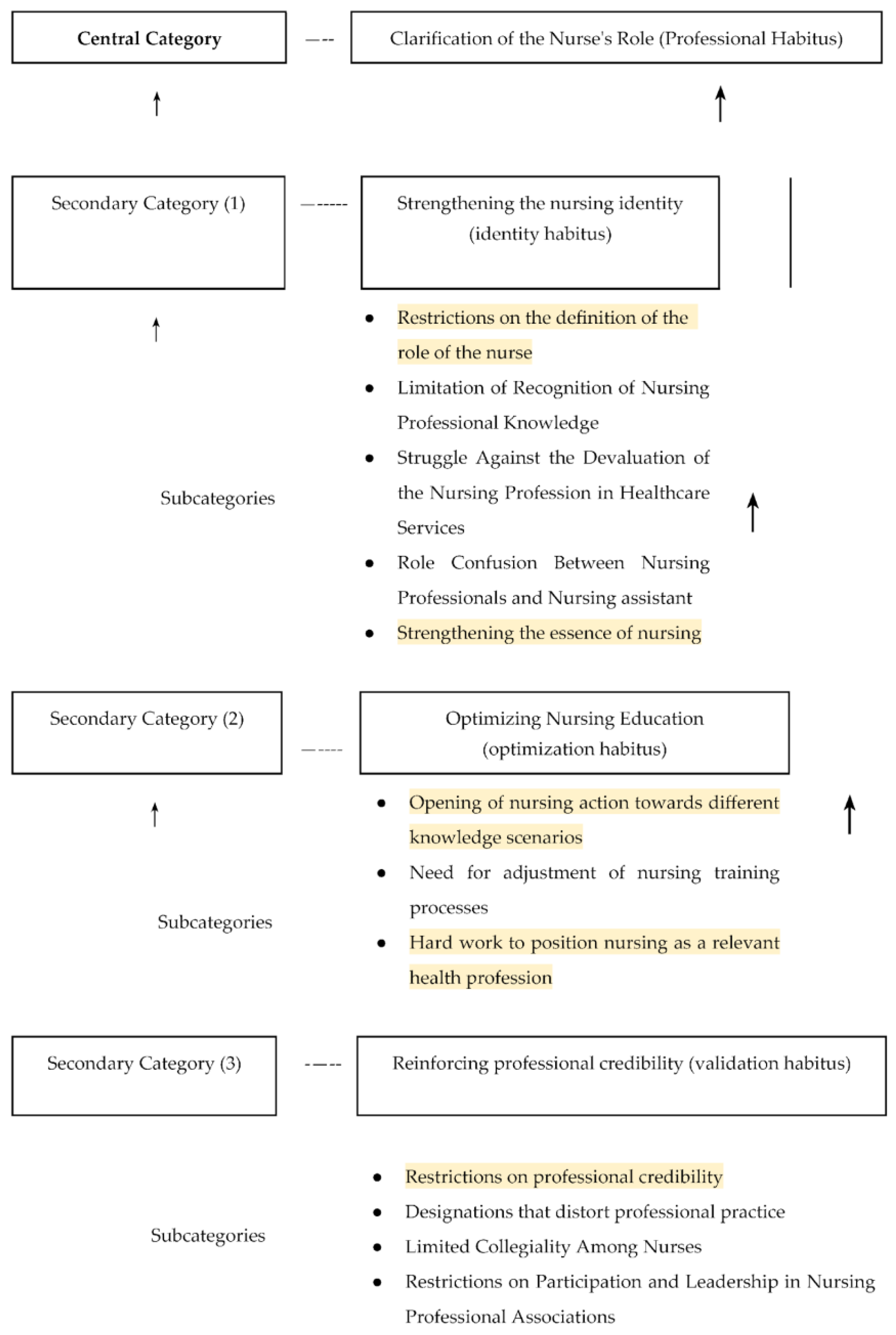

3. Results

- Strengthening the nursing identity (identity habitus);

- Optimizing nursing education (optimization habitus);

- Reinforcing professional credibility (validation habitus).

3.1. Central Category: Clarification of the Nurse’s Role (Professional Habitus)

3.2. Secondary Category: Strengthening the Nursing Identity (Identity Habitus)

3.2.1. Restrictions in Defining the Nurse’s Role

“The tension is more about the meaning of the role we perform in clinics, in institutions [...] which society has come to believe is simply a nurse who follows orders, checks on patients, and is merely an administrative entity.”(FG-E1-006)

“The primary tension arises from the fact that, as an educator, I must instill critical thinking in students. That is, with the theoretical foundation they acquire, even if they have 70 patients, they must be capable of fulfilling their role as nurses, as part of a multidisciplinary team with a legitimate voice in decision-making. [...] The main cause of the tension between theory and practice is that we do not have a socially and politically well-defined role.”(INT-CN-002)

3.2.2. Limitation of Recognition of Nursing Professional Knowledge

“I believe that power is derived from knowledge [...] Medicine continues to disregard nursing knowledge [...] in that sense, they still see themselves as ’the masters’, and while we seek to break through, we have also maintained a submissive attitude that we have not been able to shed. They have their shield, and we have ours, but we have yet to establish real sources of recognition [...].”(FG-UP-004)

“Nursing, as a field, has its own language, codes, body of knowledge, and methods of functioning that positively impact society. However, this is all part of the hegemonic discourse—nursing is always compared to medicine. In that comparison, nursing is devalued, because we are never compared in a way that highlights our strengths. The prevailing narrative is that physicians are the best. But we are different; we share a common element—human life—but each profession has its own domain [...]. The hegemonic discourse is patriarchal, it comes from a ’macho’ perspective, not even from a masculine one, but from a worldview where men dominate everything [...]. As a result, nursing care is undervalued because it is perceived as something inherent to women, as domestic work. This represents a major distortion of nursing’s image [...].”(INT-UP-002)

3.2.3. Struggle Against the Devaluation of the Nursing Profession in Healthcare Services

“Something that has bothered me since my first semester—and that happens frequently here, especially in the first five semesters—is that we are constantly being compared to medicine in every class. Here, they tell us things like: ‘We are better than medicine’, when in reality, we are different. We are a team; we need each other.”(INT-NS-007)

3.2.4. Role Confusion Between Nursing Professionals and Nursing Assistants

“Doctors and other healthcare professionals believe that nurses perform the same duties as nursing assistants. We constantly have to remind them that we graduated from a university and possess different competencies to care for patients based on professional healthcare actions.”(FG-UP-003)

“The healthcare team is still unaware of everything a nurse can do across different professional fields—whether in hospitals, community care, teaching, research, or even policymaking.”(FG-UP-006)

“I feel that a major limitation is that physicians do not acknowledge the difference between a professional nurse and a nursing assistant. When they refer to ‘the nurse’, I always have to clarify: ‘Are you talking about the nursing assistant or the registered nurse on duty?’ And then they realize—‘Oh, I was referring to the assistant.’ So I remind them that their roles are different.”(INT-P-002)

“Another thing I’ve noticed is that when a nurse is confident and has strong clarity in their actions, it is perceived as ‘stepping on doctors’ toes’, so they don’t receive due recognition. I experience this firsthand because doctors always emphasize their own contributions, while what nurses do tends to be overlooked. In this department, I have managed to establish a strong leadership presence, and we have achieved effective teamwork. However, not all nurses have the opportunity to reach that level. When I integrate all these nursing care actions to achieve positive patient outcomes, both from a medical and nursing perspective, the collaboration is highly valued. We coordinate well, communicate effectively, and work together toward that goal.”(INT-CN-005)

3.2.5. Strengthening the Essence of Nursing

“Nursing is a field that must grow in parallel with the evolving nature of the human experience to address increasing complexities. We should not simply follow medical technology advancements [...]. In reality, nursing encompasses all domains concerning the human condition, which means we must keep pace with all forms of knowledge, whether from the social sciences or biological sciences.”(FG-CN2-003)

3.3. Secondary Category: Optimizing Nursing Education (Optimization Habitus)

3.3.1. Opening of Nursing Action Towards Different Knowledge Scenarios

Beyond the medical specialty, I believe we have to think about the phenomena that concern us […] right now; for example, there is an important role in nursing care for coexistence for peace. What are we going to do about that? That generates new tools and the demand to investigate and think about ourselves in a social production of health. In Latin America, we have made many gains in understanding how our communities have developed in the inequitable relationships that have led to suffering and the conditions we have today. Nursing cannot continue to be alien to this knowledge.(GF-EA1-006)

3.3.2. Need for Adjustment of Nursing Training Processes

It is up to us to find out what I am looking for when I provide care. I want to grow in providing better care, taking into account the patient’s needs at that moment, and I have more power when I can satisfy the needs of the overwhelmed person. That is why the humanization part is very well done.(GF-E1-009)

It is not that because of the doctor’s diagnoses, we have different ways of seeing our practice. He is made to diagnose, so what is the hegemony? I am made to care; if I am doing well what I am supposed to do, there is no problem there. It is my responsibility to care as a nurse, which is my discipline: caring. That should interest us and what we have to teach our students […] I believe that we have to create another form of education.(ENT-P-004)

3.3.3. Hard Work to Position Nursing as a Relevant Health Profession

I have had the opportunity to be in different roles; I have even been on the boards. I am the only nurse who has had that opportunity here in the institution, but much to my regret, that opportunity is increasingly being lost. I feel that this is part of our responsibility because if I had had recognition, it is also because many have perceived my work as a nurse, or else, I would not have gotten there […] In most cases, we assume roles of convenience, and there is no dedication.(ENT-EA-005)

3.4. Secondary Category: Reinforcing Professional Credibility (Validation Habitus)

3.4.1. Restrictions on Professional Credibility

We have teachers who do not value their profession, so, for example, I am writing my notes, and I want to make a nursing diagnosis related to the fact that the patient has an alteration in gas exchange. Hence, the teacher comes and tells someone:—That thing about gas exchange is from respiratory therapy, so don’t go there, take it away -, and that thing about arterial blood gases? Did you analyze them? Or did you see that the doctors did it, and you copied it?(GF-E2-002)

3.4.2. Designations That Distort Professional Practice

I think it weighs heavily on us, and we must continue fighting against that view of being bosses because it is a view of the military that gives orders. Nursing leadership has to go beyond a power relationship because, often, having a staff member in charge as an auxiliary seems to be the status that we socially seek, which is different.(GF-EA1-010)

3.4.3. Limited Collegiality Among Nurses

It has to do with what we reflect from the training with the students; if a colleague does not do well with the students, how many of us are willing to ask her: what is happening? How do we support you? […] We are always in the sense of “competition”, of saying, you are good, you are bad, and then, if we ourselves, as in the teaching exercise, are not supportive of the other, we are impregnating that same thing in our students.(ENT-EA-008)

3.4.4. Restrictions on Participation and Leadership in Nursing Professional Associations

I am still determining the role the ANEC (National Association of Nurses of Colombia) union plays. I think there should also be, I do not know, a redefinition, a collective construction, or something that leads us to think about and build a different union […]. If we lack it, perhaps some external help from these organizations can strengthen our leadership.(ENT-EA-008)

4. Discussion

4.1. Habitus and Autonomy in Nursing Practice

4.2. The Healthcare Field and Autonomy in Nursing Practice

4.3. Capital and Autonomy in Nursing Practice

4.4. Proposed Solutions and Recommendations

- Expanding academic training, strengthening nursing research, and disseminating the impact of the discipline;

- Adjusting the structure of nursing education programs to go beyond technical skill development, ensuring that students acquire critical thinking, ethical reasoning, and leadership abilities that enable them to recognize themselves as political agents with autonomy within the healthcare field;

- Integrating practical experiences that encourage reflection on the relevance of the nursing role, professional values, and contributions to patient care;

- Transforming workplace environments to ensure that nurses have the necessary conditions to practice autonomously and effectively, supported by health and organizational policies that respect and value their clinical judgment and decision-making, as well as fair compensation;

- Balancing administrative workloads and excessive working hours, allowing nurses to focus on delivering high-quality patient care.

4.5. Strengths

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griffiths, P.; Recio-Saucedo, A.; Dall’Ora, C.; Briggs, J.; Maruotti, A.; Meredith, P.; Smith, G.B.; Ball, J.; The Missed Care Study Group. The Association between Nurse Staffing and Omissions in Nursing Care: A Systematic Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 1474–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenway, K.; Butt, G.; Walthall, H. What Is a Theory-Practice Gap? An Exploration of the Concept. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 34, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.-J.; Kim, S.-Y. Transition Shock Experience of Nursing Students in Clinical Practice: A Phenomenological Approach. Healthcare 2022, 10, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safazadeh, S.; Irajpour, A.; Alimohammadi, N.; Haghani, F. Exploring the Reasons for Theory-Practice Gap in Emergency Nursing Education: A Qualitative Research. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Alomari, A.M.A.; Sayed, H.M.A.; Mannethodi, K.; Kunjavara, J.; Joy, G.V.; Hassan, N.; Martinez, E.; Lenjawi, B.A. Barriers and Solutions to the Gap between Theory and Practice in Nursing Services: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Evidence. Nurs. Forum 2024, 2024, 7522900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, B.F.Y.; Zhou, W.; Lim, T.W.; Tam, W.W.S. Practice Patterns and Role Perception of Advanced Practice Nurses: A Nationwide Cross-sectional Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. El Sentido Práctico; Primera edición de Siglo XXI en España; Siglo XXI: Madrid, Spain, 2008; ISBN 978-84-323-1302-8. [Google Scholar]

- Moya, J.L.M.; Backes, V.M.S.; Prado, M.L.D.; Sandin, M.P. La Enfermería Como Grupo Oprimido: Las Voces de Las Protagonistas. Texto Contexto-Enferm. 2010, 19, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhi-Balasi, L.; Elahi, N.; Ebadi, A.; Jahani, S.; Hazrati, M. Professional Autonomy of Nurses: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis Study. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2020, 25, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J.; McCarthy, T.A.; Habermas, J. Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason. In The Theory of Communicative Action, 1st digital-print ed.; Thomas MacCarthy, T., Translator; Beacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-8070-1401-1. [Google Scholar]

- Delanty, G.; Strydom, P. (Eds.) Philosophies of Social Science: The Classic and Contemporary Readings; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-335-20884-5. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Qualitative Sozialforschung: Eine Einführung, 10th ed.; Rororo Rowohlts Enzyklopädie; Rowohlts Enzyklopädie im Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag: Reinbek bei Hamburg, Germany, 2021; ISBN 978-3-499-55694-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rhynas, S.J. Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice and Its Potential in Nursing Research. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 50, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.; Korstjens, I. Series: Practical Guidance to Qualitative Research. Part 3: Sampling, Data Collection and Analysis. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA; Boston, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4129-9746-1. [Google Scholar]

- Binding, L.L.; Tapp, D.M. Human Understanding in Dialogue: Gadamer’s Recovery of the Genuine. Nurs. Philos. 2008, 9, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debesay, J.; Nåden, D.; Slettebø, Å. How Do We Close the Hermeneutic Circle? A Gadamerian Approach to Justification in Interpretation in Qualitative Studies. Nurs. Inq. 2008, 15, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdieu, P.; Kauf, T. Razones Prácticas: Sobre la Teoría de la Acción, 4th ed.; Anagrama: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; ISBN 978-84-339-0543-7. [Google Scholar]

- Shirk, J.D.; Laviana, A.; Lambrechts, S.; Kwan, L.; Pagan, C.; Sumal, A.; Saigal, C. Decisional Quality in Patients with Small Renal Masses. Urology 2018, 116, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahiane, L.; Zaam, Y.; Abouqal, R.; Belayachi, J. Factors Associated with Recognition at Work among Nurses and the Impact of Recognition at Work on Health-Related Quality of Life, Job Satisfaction and Psychological Health: A Single-Centre, Cross-Sectional Study in Morocco. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e051933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajani, K.; Moez, S. Gap between Knowledge and Practice in Nursing. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 15, 3927–3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Gil, T.; Martínez Gimeno, L.; Luengo González, R. Antropología de Los Cuidados En El Ámbito Académico de La Enfermería En Espanã. Texto Contexto-Enferm. 2006, 15, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Arellano, O.; Jarillo-Soto, E.C. A health system’s neoliberal reform: Evidence from the Mexican case. Cad. Saúde Pública 2017, 33, e00087416. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, T.A.D.; Freitas, G.F.D.; Takashi, M.H.; Albuquerque, T.D.A. Professional Identity of Nurses: A Literature Review. Enf. Glob. 2019, 18, 563–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, V.; Caballero, C. El concepto de Reconocimiento y su utilidad para el campo de la enfermería. Temperamentvm 2020, 16. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?pid=S1699-60112020000100019&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Pierrotti, V.W.; Guirardello, E.D.B.; Toledo, V.P. Nursing Knowledge Patterns: Nurses’ Image and Role in Society Perceived by Students. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20180959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. State of the World’s Nursing 2020: Investing in Education, Jobs and Leadership; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-92-4-000327-9. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, R. Gender, Health and Theory: Conceptualizing the Issue, in Local and World Perspective. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1675–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, K.; Falk, H.; Jakobsson Ung, E. When Practice Precedes Theory—A Mixed Methods Evaluation of Students’ Learning Experiences in an Undergraduate Study Program in Nursing. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2016, 16, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Rey, F. De La Práctica de La Enfermería a La Teoría Enfermera: Concepciones Presentes en el Ejercicio Profesional. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Alcalá, Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zohoorparvandeh, V.; Farrokhfall, K.; Ahmadi, M.; Dashtgard, A. Investigating Factors Affecting the Gap of Nursing Education and Practice from students and instructors’ viewpoints. Future Med. Educ. J. 2018, 8, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, P.; Özmen, G.Ç.; Yavuz, M.E.; Koçan, S.; Çilingir, D. Exploration of Nursing Students’ Views on the Theory-Practice Gap in Surgical Nursing Education and Its Relationship with Attitudes towards the Profession and Evidence-Based Practice. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 69, 103624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, F.V. Ideas educacionales de Paulo Freire. Reflexiones desde la educación superior Paulo Freire’s educational ideas. Reflections from higher education. Medisur 2020, 18, 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Moya, J.L.M.; Parra, S.C. La Enseñanza de La Enfermería Como Una Práctica Reflexiva. Texto Contexto-Enferm. 2006, 15, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz Riveros, C. La Naturaleza Del Cuidado Humanizado. Enfermeria 2020, 9, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerril, L.C.; Rojas, A.M.; Gómez, B.A. Importancia del pensamiento reflexivo y crítico en enfermería. Enfermería Cardiologica 2015, 23, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zappas, M.; Walton-Moss, B.; Sanchez, C.; Hildebrand, J.A.; Kirkland, T. The Decolonization of Nursing Education. J. Nurse Pract. 2021, 17, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Role | Profession/Gender | Quantity | Age (Years) | Highest Level of Education Attained | Teaching Experience (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professor | Female Nurse | 5 | 38–67 | Master’s (5) | 10–30 |

| Male Nurse | 1 | 43 | PhD (1) | 22 | |

| Clinical Nurse | Female Nurse | 10 | 30–61 | Master’s (9); PhD (1) | 3–27 |

| Male Nurse | 1 | 38 | Master’s (1) | 16 | |

| Nursing Students | Female | 11 | 21–24 | High School (11) | None |

| Male | 6 | 21–24 | High School (6) | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piedrahita Sandoval, L.E.; Sotelo-Daza, J.; Morales Viana, L.C.; Aviles Gonzalez, C.I. How Does Professional Habitus Impact Nursing Autonomy? A Hermeneutic Qualitative Study Using Bourdieu’s Framework. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030088

Piedrahita Sandoval LE, Sotelo-Daza J, Morales Viana LC, Aviles Gonzalez CI. How Does Professional Habitus Impact Nursing Autonomy? A Hermeneutic Qualitative Study Using Bourdieu’s Framework. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(3):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030088

Chicago/Turabian StylePiedrahita Sandoval, Laura Elvira, Jorge Sotelo-Daza, Liliana Cristina Morales Viana, and Cesar Ivan Aviles Gonzalez. 2025. "How Does Professional Habitus Impact Nursing Autonomy? A Hermeneutic Qualitative Study Using Bourdieu’s Framework" Nursing Reports 15, no. 3: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030088

APA StylePiedrahita Sandoval, L. E., Sotelo-Daza, J., Morales Viana, L. C., & Aviles Gonzalez, C. I. (2025). How Does Professional Habitus Impact Nursing Autonomy? A Hermeneutic Qualitative Study Using Bourdieu’s Framework. Nursing Reports, 15(3), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030088