Assertiveness in Nursing: A Systematic Review of Its Role and Impact in Healthcare Settings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Electronic Databases

2.4. Search Strategy

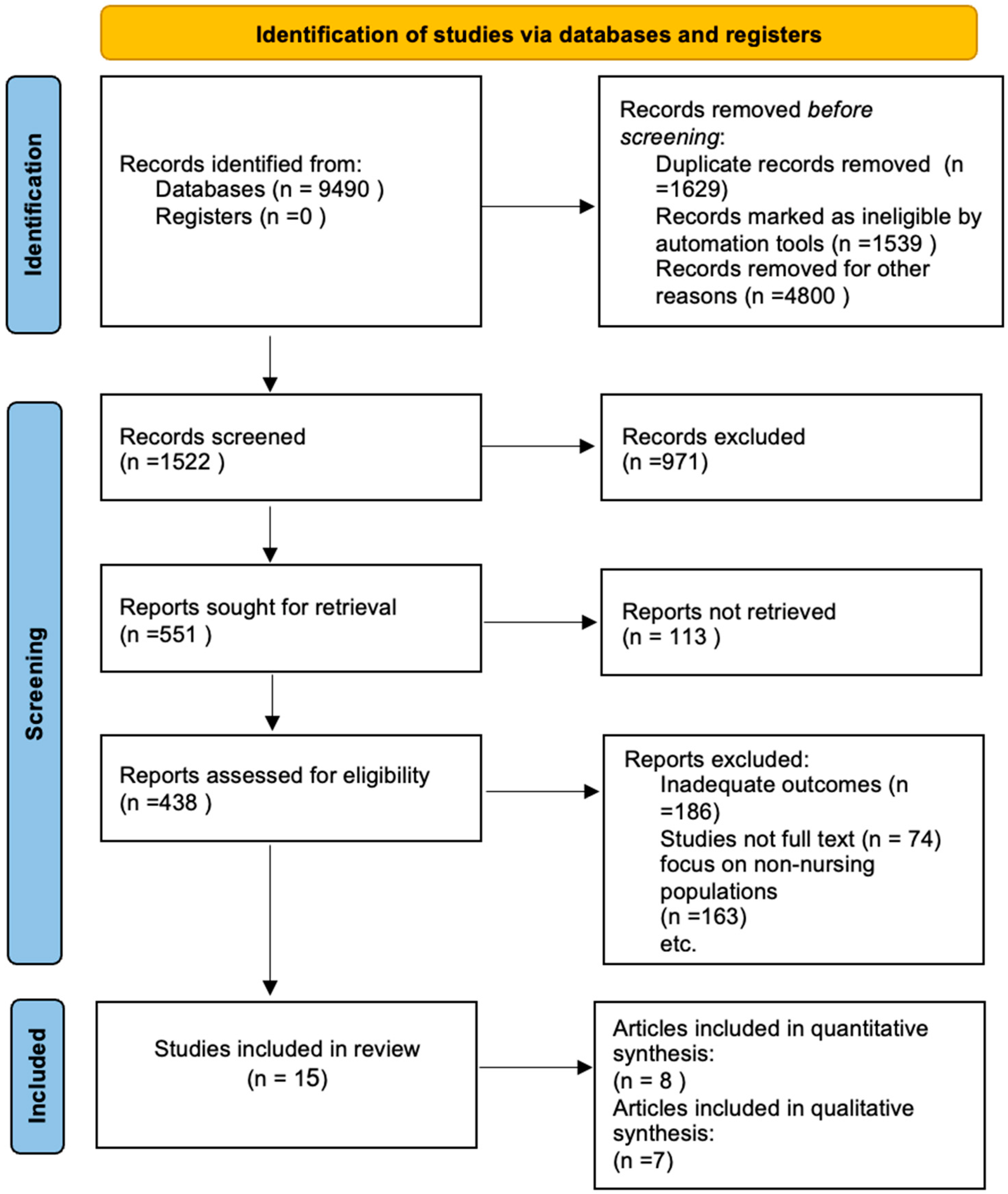

2.5. Study Selection

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Quality Appraisal and Assessment of Risk of Bias

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Analytical Findings

3.2.1. Facilitators of Assertiveness

3.2.2. Barriers to Assertiveness in Nursing

3.2.3. Assertiveness Training

3.2.4. Interaction with Other Staff

3.2.5. Patient Relationship

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Program |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SPIDER | Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type |

Appendix A

- Summary of the quality using JBI and CASP checklist;

- Risk of bias summary according to each domain.

| CASP Items | Mansour & Mattukoyya [20] | Omura et al. [21] | Lee et al. [22] | Law & Chan [24] | Mahmoudirad et al. [23] | Omura, Stone, & Levett-Jones [25] | Omura, Stone, & Levett-Jones [26] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Is there a clear statement of findings? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| How valuable is the research? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Total score | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| JBI Items Quasi-Experimental Studies | Abdelaziz et al. [1] | Mostafa et al. [14] | Mohammed et al. [15] | Khanam et al. [16] | Nemati et al. [13] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is it clear in the study what is the ‘cause’ and what is the ‘effect’ (i.e., there is no confusion about which variable comes first)? | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Were the participants included in any comparisons similar? | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Were the participants included in any comparisons receiving similar treatment/care, other than the exposure or intervention of interest? | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Was there a control group? | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Were there multiple measurements of the outcome both pre and post the intervention/exposure? | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Was follow up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analyzed? | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Were the outcomes of participants included in any comparisons measured in the same way? | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Total Score | 27 | 23 | 20 | 23 | 24 |

| JBI Items Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies | Marahatta & Koirala [19] | Wehabe et al. [17] | Oducado & Montaño [18] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Were confounding factors identified? | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Total Score | 22 | 17 | 19 |

References

- Abdelaziz, E.M.; Diab, I.A.; Ouda, M.M.A.; Elsharkawy, N.B.; Abdelkader, F.A. The effectiveness of assertiveness training program on psychological wellbeing and work engagement among novice psychiatric nurses. Nurs. Forum 2020, 55, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushtaq, B. Assertiveness in Nursing. COJ Nurs. Health Care 2018, 3, 272–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omura, M.; Maguire, J.; Levett-Jones, T.; Stone, T.E. The effectiveness of assertiveness communication training programs for healthcare professionals and students: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 76, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bril, I.; Boer, H.J.; Degens, N.; Fleer, J. Nursing students’ experiences with clinical placement as a learning environment for assertiveness: A qualitative interview study. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2022, 17, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfatah, E.E.A.; Wahab, E.A.; Sayed, H.H.E. Assertiveness and absenteeism and their relation to career development among nursing personnel at Benha University Hospital. Egypt. J. Health Care 2018, 9, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C.A.; Querido, A.I. Assertiveness training of novice psychiatric nurses: A necessary approach. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 42, 699–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The Prisma 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Using mixed methods in health and social care research. In Health and Social Care Research Methods in Context; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarberg, K.; Kirkman, M.; de Lacey, S. Qualitative research methods: When to use them and how to judge them. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.H.; Habibi, N.; Aromataris, E.; Stone, J.C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Sears, K.; Hasanoff, S.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Moola, S.; et al. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for quasi-experimental studies. JBI Evid. Synth. 2024, 10, 11124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P. Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nemati, Z.; Maghsoudi, S.; Mazloum, S.R.; Kalatemolaey, M. Evaluating effect of assertive training program on assertiveness communication and self-concept of nurses. J. Sabzevar Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 29, 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, S.M.; Desouki, H.H.; Mourad, G.M.; Barakat, M.M. Effect of Assertiveness Training Program on Psychiatric Mental Health Nurses’ Communication Skills and Self-esteem. J. Nurs. Sci. Benha Univ. 2022, 3, 738–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.E.S.; Shazly, M.M.; Mostafa, H.A. Communication skills training program and its effect on head nurses’ assertiveness and self-esteem. Egypt. J. Health Care 2022, 13, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, S.; Abdullahi, K.O.; Sarwar, H.; Altaf, M. The effect of assertiveness-based programme on psychological wellbeing and work engagement among novice nurses in psychiatric department. Med. Forum 2023, 34, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed Abdel Wehabe, A.; Faisal Fakhry, S.; Abd ELazeem Mostafa, H. Assertiveness and leadership styles among head nurses. Egypt. J. Health Care 2018, 9, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oducado, R.M.F.; Montaño, H.C. Workplace Assertiveness of Filipino Hospital Staff Nurses: A Cross-sectional Study. Nurse Media J. Nurs. 2021, 11, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marahatta, U.S.; Koirala, D. Assertiveness and self-esteem among nurses working at a teaching hospital, Bharatpur, Chitwan. MedS Alliance J. Med. Med. Sci. 2022, 2, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.; Mattukoyya, R. Development of assertive communication skills in nursing preceptorship programmes: A qualitative insight from newly qualified nurses. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 26, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omura, M.; Stone, T.E.; Maguire, J.; Levett-Jones, T. Exploring Japanese nurses’ perceptions of the relevance and use of assertive communication in healthcare: A qualitative study informed by the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 67, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Dahinten, V.S.; Ji, H.; Kim, E.; Lee, H. Motivators and inhibitors of nurses’ speaking up behaviours: A descriptive qualitative study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 3398–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudirad, G.; Ahmadi, F.; Vanaki, Z.; Hajizadeh, E. Assertiveness process of Iranian nurse leaders: A grounded theory study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2009, 11, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, B.Y.; Chan, E.A. The experience of learning to speak up: A narrative inquiry on newly graduated registered nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 1837–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omura, M.; Stone, T.E.; Levett-Jones, T. Cultural factors influencing Japanese nurses’ assertive communication. Part 1: Collectivism. Nurs. Health Sci. 2018, 20, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omura, M.; Stone, T.E.; Levett-Jones, T. Cultural factors influencing Japanese nurses’ assertive communication: Part 2—Hierarchy and power. Nurs Health Sci. 2018, 20, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrow, K.J.; Gustavson, A.M.; Jones, J. Speaking up behaviours (safety voices) of healthcare workers: A metasynthesis of qualitative research studies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 64, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuyama, A.; Wagner, C.; Bijnen, B. Speaking up for patient safety by hospital-based health care professionals: A literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J. New graduate nurses’ experiences about lack of professional confidence. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 19, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwappach, D.; Richard, A. Speak up-related climate and its association with healthcare workers’ speaking up and withholding voice behaviours: A cross-sectional survey in Switzerland. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2018, 27, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, J.; Simmons, R.; Barnard, J. Assertion practices and beliefs among nurses and physicians on an inpatient Pediatric Medical Unit. Hosp. Pediatr. 2016, 6, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oducado, R.M. Influence of self-esteem, psychological empowerment, and empowering leader behaviors on assertive behaviors of staff nurses. Belitung Nurs. J. 2021, 7, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwappach, D.L.; Niederhauser, A. Speaking up about patient safety in psychiatric hospitals—A cross-sectional survey study among healthcare staff. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, E.; Khurshid, Z.; Anjara, S.; De Brún, A.; Rowan, B.; McAuliffe, E. P92 Power dynamics in healthcare teams—A barrier to team effectiveness and patient safety: A systematic review. BJS Open 2021, 5 (Suppl. S1), zrab032-091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenz, H.; Burtscher, M.J.; Grande, B.; Kolbe, M. Nurses’ voice: The role of hierarchy and leadership. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2020, 33, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Choi, J.; Lee, H.; Sang, S.; Lee, H.; Hong, H.C. Factors influencing nurses’ willingness to speak up regarding patient safety in East Asia: A systematic review. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 1053–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Yoshinaga, N.; Tanoue, H.; Kato, S.; Nakamura, S.; Aoishi, K.; Shiraishi, Y. Development and evaluation of a modified brief assertiveness training for nurses in the workplace: A single-group feasibility study. BMC Nurs. 2017, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, E.; Kanoya, Y.; Katsuki, T.; Sato, C. Assertiveness affecting burnout of novice nurses at university hospitals. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2006, 3, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parray, W.M.; Kumar, S. Impact of assertiveness training on the level of assertiveness, self-esteem, stress, psychological well-being and academic achievement of adolescents. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2017, 8, 1476–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Ayhan, D.; Öz, H.S. Effect of assertiveness training on the nursing students’ assertiveness and self-esteem levels: Application of hybrid education in COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs. Forum 2021, 56, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadavi, M.; Abdorrazagh Nejad, M. Assertive behaviors among nursing staff in a local hospital in Iran. Mod. Care J. 2018, 15, e80765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.A. Factors affecting assertiveness among student nurses. Nurse Educ. Today 2011, 31, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, S.K.; Gill, K.K. Relationship of assertiveness and self-esteem among nurses. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2015, 5, 440–449. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El Gawad, Z.; Gad, E.; Abd El, K.E.; Lachine, O. The effect of assertive training techniques on improving coping skills of nurses in psychiatric set up. Archaeol. Soc. N. J. 2007, 6, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Timmins, F.; McCabe, C. Nurses’ and midwives’ assertive behaviour in the workplace. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 51, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainer, J. Speaking Up: Factors and Issues in Nurses Advocating for Patients When Patients Are in Jeopardy. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2015, 30, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwappach, D.L.; Gehring, K. Trade-offs between voice and silence: A qualitative exploration of oncology staff’s decisions to speak up about safety concerns. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements of SPIDER | Elements of SPIDER as Applied to This Review |

|---|---|

| S—Sample | Registered nurses. |

| PI—Phenomenon of Interest | Assertiveness. |

| D—Design | Studies using qualitative or quantitative designs. |

| E—Evaluation | Nurses’ experiences, perceptions, and opinions; views related to assertiveness. |

| R—Research type | Primary research sources of both qualitative and quantitative research designs. |

| Author | Year | Country | Aim/Objective | Sample Work Environment | Design | Tools | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelaziz et al. [1] | 2020 | Egypt | Effectiveness of an assertiveness training program on psychological well-being and work engagement among novice psychiatric nurses. | 36 novice psychiatric nurses at The Abbasia hospital for mental health. | Quasi-experimental design. | Socio-demographic data sheet, Rathus Assertiveness Schedule, Riff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale, and Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. | Statistically significant improvement in assertiveness skills, psychological well-being, and work engagement. Positive correlation between assertiveness skills and psychological well-being. | Assertiveness training improves well-being and engagement in novice nurses, suggesting benefit in structured training programs for skills development. |

| Mostafa et al., [14] | 2022 | Egypt | Assess the effect of an assertiveness training program on communication skills and self-esteem among psychiatric nurses. | 50 nurses at the Psychiatric Mental Health Hospital. | Quasi-experimental design. | I: Structured interview questionnaire. II: Rosenberg’s Global Self-esteem Scale. III: Assertiveness skills scale. IV: Communication Skills Inventory. | Significant improvement in self-esteem, assertiveness, and communication skills post-training. | Training enhanced essential interpersonal skills, promoting self-confidence and patient care quality. |

| Mohammed et al., [15] | 2022 | Egypt | Assess communication skills training impact on head nurses’ assertiveness and self-esteem. | 50 head nurses at Nasser Institute Hospital for Research and Treatment. | Quasi-experimental design. | The data of this study were collected through three tools, namely, a knowledge questionnaire, an Assertiveness Assessment Scale, and a Sorensen Self-Esteem Scale. | Improved knowledge, assertiveness, and self-esteem post-intervention. Assertiveness increased from 70% to 94%; self-esteem increased from 34% to 78% (p < 0.001). | Communication training effectively boosted assertiveness and self-esteem. |

| Khanam et al. [16] | 2023 | Pakistan | Evaluate effectiveness of assertiveness training on psychological well-being and work engagement among novice nurses. | 36 novice nurses working in a psychiatric department. | Quasi-experimental design. | Assertiveness, psychological well-being, and work-engagement was collected using three adopted questionnaires. | Significant increase in psychological well-being (132.14 to 188.06), assertiveness (8.94 to 34.56), and work engagement (65.17 to 78.39). | Training supports psychological well-being and engagement, enhancing adaptability and resilience for novice nurses. |

| Nemati et al., [13] | 2021 | Iran | Evaluate impact of assertiveness training program on assertiveness and self-esteem among nurses. | 70 nurses at Imam Reza Hospital. | Experimental design. | The Coopersmith Self-Esteem Questionnaire, the Omali and Bachman Self-Esteem Scale, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and the self-reporting questionnaire. | Intervention group showed increased assertiveness and self-esteem post-intervention, but not significant compared to control group. | Training led to improvement, but long-term or more intensive programs may be needed to achieve lasting results. |

| Oducado and Montaño [18] | 2021 | Philippines | Assess workplace assertiveness among hospital staff nurses toward colleagues, management, and other health team members. | 223 nurses at two tertiary hospitals. | Cross-sectional design. | Workplace assertive behavior questionnaire. Descriptive statistics and tests for differences were used to analyze the data. | Moderate assertiveness in workplace. Assertiveness varied by employment status, age, experience, and organizational tenure. | Assertiveness influenced by workplace hierarchy and norms, indicating need for management support to foster assertive communication. |

| Wehabe et al., [17] | 2018 | Egypt | Investigate relationship between assertiveness and leadership styles among head nurses. | 98 head nurses at Ain-Shams University Hospitals. | Analytic cross-sectional design. | A self-administered questionnaire which included two different tools, assertiveness scale and the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ). | A total of 77.6% had high assertiveness; assertiveness correlated with transformational and transactional leadership styles and negatively correlated with passive/avoidant styles. | Assertiveness positively linked with proactive leadership, suggesting assertiveness training could enhance leadership effectiveness in healthcare. |

| Marahatta & Koirala, [19] | 2022 | Nepal | The objective of the study was to find out the level of assertiveness and self-esteem. | 155 nurses at Chitwan Medical College, Teaching Hospital. | Descriptive cross-sectional design. | Self-administered structured questionnaire consisted of three parts. First part consists of socio-demographic and professional information, second part consists of Simple Rathus Assertiveness Schedule (SRAS), and third part consists of Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES). | A total of 51% high assertiveness, 54.8% high self-esteem. Assertiveness and self-esteem associated with age, ethnicity, residence, marital status, education, and job satisfaction. | Many nurses show low assertiveness and self-esteem, highlighting a need for training to boost confidence and patient care. |

| Mansour, M., & Mattukoyya, R. [20] | 2019 | East England | To examine newly qualified nurses’ views on how nursing preceptorship programs contribute to shaping their assertive communication skills. | 42 nurses from four acute hospital trusts in east England. | Cross-sectional design. | Open-ended questions included in a cross-sectional survey that was analyzed using thematic analysis. | Themes included enthusiasm vs. skepticism, supportive work culture, and logistical challenges. | Preceptorship programs support assertive communication skills. Ongoing support and organizational commitment needed. |

| Omura et al. [21] | 2018 | Japan | Explore nurses’ perceptions of assertive communication in Japanese healthcare and identify factors impacting assertiveness. | 23 nurses at workplaces or universities. | A belief elicitation qualitative study informed by the Theory of Planned Behavior. | Individual face-to-face semi-structured interviews. | Hierarchies, age-based seniority, and fear of offending colleagues hindered assertive communication. Novice nurses reluctant to speak up. | Hierarchical and cultural barriers affect assertive communication, suggesting need for culturally adapted assertiveness training. |

| Lee et al., [22] | 2022 | Korea | Identify factors motivating or inhibiting nurses’ speaking-up behaviors. | 15 nurses from four Korean hospitals. | Descriptive qualitative design. | Semi-structured interviews. | Speaking up motivated by safety culture, supportive managers, and role models and inhibited by hierarchies, seniority, and heavy workload. | Cultural and organizational factors significantly influence speaking-up behavior, underlining the need for a supportive work culture to encourage open communication for patient safety. |

| Mahmoudirad et al., [23] | 2009 | Iran | Explore the assertiveness process among Iranian nursing leaders. | 12 nurse managers working in four hospitals in Iran. | Grounded theory qualitative design. | Semi-structured interviews. | Assertiveness influenced by external/internal factors and shaped significantly by religious beliefs. | Assertiveness in Iranian nurse leaders is shaped by cultural and religious values, suggesting the need for training that respects these influences. |

| Law & Chan, [24] | 2015 | Hong Kong | Explore the learning process of speaking up among newly graduated nurses. | 18 newly graduated nurses from seven public hospitals in Hong Kong. | Narrative qualitative design. | Unstructured interviews and emails. | Identified need for ongoing mentoring and creation of safe communication environments as critical for empowering nurses to speak up. | New nurses benefit from mentoring and supportive environments for developing assertive communication, particularly in hierarchical cultures like Hong Kong. |

| Omura, Stone, & Levett-Jones [25] | 2018 | Japan | Explore cultural influences on Japanese nurses’ assertive communication. | 23 registered nurses in hospitals, communities, and educational institutions. | Descriptive qualitative design. | Face-to-face interviews with a semi-structured format. | Cultural values of “wa” (harmony), collectivism, and hierarchy inhibit assertive communication. Speaking up perceived as disruptive to team harmony. | Training programs should be culturally adapted, addressing barriers like collectivism and hierarchy to support assertive communication in Japanese healthcare settings. |

| Omura, Stone, & Levett-Jones [26] | 2018b | Japan | Investigate hierarchy and power’s impact on Japanese nurses’ assertive communication. | 23 registered nurses in hospitals, communities, and educational institutions. | Phenomenological qualitative design. | Face-to-face interviews with a semi-structured format. | Identified hierarchy, professional status, seniority, gender imbalance, and cultural humility as barriers to assertive communication. | Assertiveness training must account for hierarchical and cultural values, emphasizing indirect communication strategies for effective adaptation in Japanese healthcare. |

| Study | Training | Barriers | Facilitators | Patient Relationships | Interaction with Other Staff | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abdulaziz et al. [1] | X | X | |||

| 2 | Mostafa et al., [14] | X | X | X | X | |

| 3 | Mansour and Mattukoyya [20] | X | X | X | X | X |

| 4 | Marahatta and Koirala [19] | X | X | X | ||

| 5 | Wehabe et al., [17] | X | X | X | X | |

| 6 | Mohammed et al. [15] | X | X | X | ||

| 7 | Nemati et al. [13] | X | X | X | X | |

| 8 | Oducado and Montaño [18] | X | X | X | X | X |

| 9 | Khanam et al. [16] | X | X | X | X | |

| 10 | Omura et al. [21] | X | X | X | X | X |

| 11 | Lee et al., [22] | X | X | X | ||

| 12 | Law & Chan [24] | X | X | X | X | |

| 13 | Mahmoudirad et al., [23] | X | X | X | X | |

| 14 | Omura, Stone, & Levett-Jones [25] | X | X | X | ||

| 15 | Omura, Stone, & Levett-Jones [26] | X | X | X |

| Theme | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Facilitators of assertiveness |

|

| Barriers to assertiveness |

|

| Assertiveness training |

|

| Interaction with other staff |

|

| Patient relationship |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-hawaiti, M.R.; Sharif, L.; Elsayes, H. Assertiveness in Nursing: A Systematic Review of Its Role and Impact in Healthcare Settings. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030102

Al-hawaiti MR, Sharif L, Elsayes H. Assertiveness in Nursing: A Systematic Review of Its Role and Impact in Healthcare Settings. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(3):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030102

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-hawaiti, Maha R., Loujain Sharif, and Hala Elsayes. 2025. "Assertiveness in Nursing: A Systematic Review of Its Role and Impact in Healthcare Settings" Nursing Reports 15, no. 3: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030102

APA StyleAl-hawaiti, M. R., Sharif, L., & Elsayes, H. (2025). Assertiveness in Nursing: A Systematic Review of Its Role and Impact in Healthcare Settings. Nursing Reports, 15(3), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030102