Factor Structure of the Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-COPE) in Chinese Nursing Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Measures

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

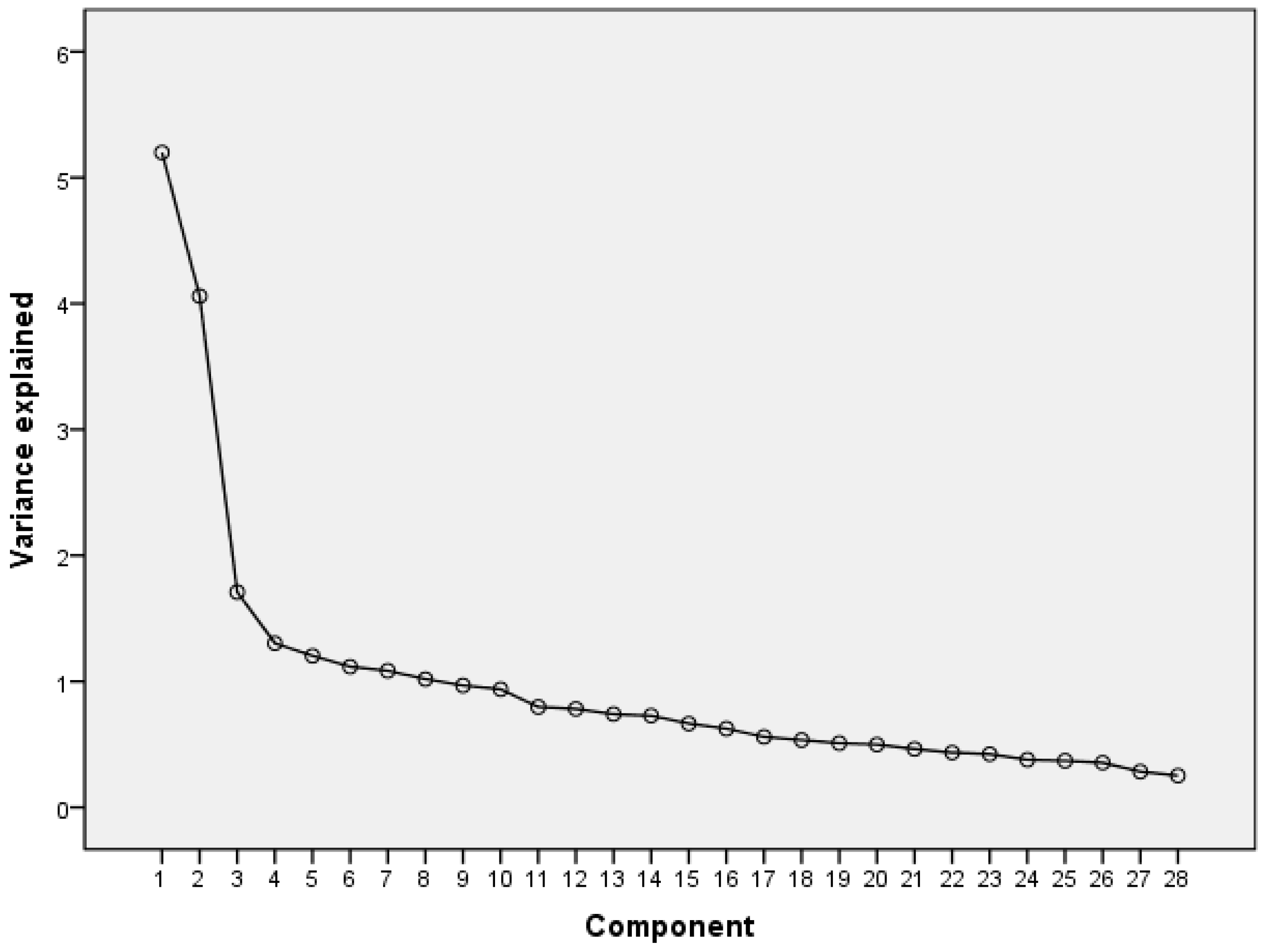

3.2. Factor Analysis Results

3.2.1. Positive Reframing Coping

3.2.2. Avoidant and Passive Coping

3.2.3. Seeking Social Support

3.2.4. Self-Blame and Emotional Distress Coping

3.2.5. Denial and Deflective Coping

3.2.6. Spirituality and Humor Coping

3.2.7. Avoidance and Emotional Release Coping

3.2.8. Adaptive Acceptance with Distraction

3.3. Reliability Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications of Brief-COPE for Nursing

4.3. Recommendations for Enhancing Coping for Nursing Students

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Admi, H.; Moshe-Eilon, Y.; Sharon, D.; Mann, M. Nursing students’ stress and satisfaction in clinical practice along different stages: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 68, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, K.; McCarthy, V.L. Stress and anxiety among nursing students: A review of intervention strategies in literature between 2009 and 2015. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2017, 22, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulido-Martos, M.; Augusto-Landa, J.; Lopez-Zafra, E. Sources of stress in nursing students: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2012, 59, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H.F.; Alzahrani, J.; Hamed, A.; Althagafi, A.; Alkarani, A.S. The Experiences of Newly Graduated Nurses during Their First Year of Practice. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeve, K.L.; Shumaker, C.J.; Yearwood, E.L.; Crowell, N.A.; Riley, J.B. Perceived stress and social support in undergraduate nursing students’ educational experiences. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoliker, B.E.; Lafreniere, K.D. The influence of perceived stress, loneliness, and learning burnout on university students’ educational experience. Coll. Stud. J. 2015, 49, 146–160. [Google Scholar]

- Holinka, C. Stress, emotional intelligence, and life satisfaction in college students. Coll. Stud. J. 2015, 49, 300–311. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. Eur. J. Pers. 1987, 1, 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penley, J.A.; Tomaka, J.; Wiebe, J.S. The Association of Coping to Physical and Psychological Health Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Behav. Med. 2002, 25, 551–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, M.; Howell, D.; McCorry, N.K. Illness perceptions and coping in physical health conditions: A meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 79, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.; McEnroe-Petitte, D.; Al Amri, M.; Fronda, D.; Obeidat, A. An integrative review on coping skills in nursing students: Implications for policymaking. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2018, 65, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabane, S.; Chaabna, K.; Bhagat, S.; Abraham, A.; Doraiswamy, S.; Mamtani, R.; Cheema, S. Perceived stress, stressors, and coping strategies among nursing students in the Middle East and North Africa: An overview of systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Jin, S.-X.; Quan, Y.-X.; Zhang, X.-W.; Cui, X.-S. The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on nursing students: A meta-analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 98, 104718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Guo, X.; Soh, K.L.; Japar, S.; He, L. Effectiveness of stress management interventions for nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs. Health Sci. 2024, 26, e13113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente, L.; Vera, M.; Peiró, T. Nurses’ stressors and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of coping and resilience. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 1335–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. The relationship between coping and emotion: Implications for theory and research. Soc. Sci. Med. 1988, 26, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endler, N.S.; Parker, J.D. Multidimensional assessment of coping: A critical evaluation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.K.; Nicassio, P.M. Development of a questionnaire for the assessment of active and passive coping strategies in chronic pain patients. Pain 1987, 31, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, M.A.; Gridley, M.K.; Peters, R.M. The Factor Structure of the Brief Cope: A Systematic Review. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 44, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Martín, F.D.; Flores-Carmona, L.; Arco-Tirado, J.L. Coping Strategies Among Undergraduates: Spanish Adaptation and Validation of the Brief-COPE Inventory. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, K.; Saito, M.; Takao, T. Stress and coping styles in Japanese nursing students. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2012, 18, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niegocki, K.L.; Ægisdóttir, S. College Students’ Coping and Psychological Help-Seeking Attitudes and Intentions. J. Ment. Health Couns. 2019, 41, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masilamani, R.; Aung, M.M.T.; Othman, H.; Bakar, A.A.; Keat, T.C.; Ravichandran, S.; Wing, L.K.; Hong, C.W.; Hong, L.K.; Elson, N.; et al. Stress, stressors and coping strategies among university nursing students. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2019, 19, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Selman, R.L.; Haste, H. Academic stress in Chinese schools and a proposed preventive intervention program. Cogent Educ. 2015, 2, 1000477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, K.H. Massification of higher education, graduate employment and social mobility in the Greater China region. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2016, 37, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Yang, C.; Inder, K.; Chan, S.W. Psychometric properties of Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced in patients with multiple chronic conditions: A preliminary study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2022, 28, e12955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New International Edition; Pearson Deutschland: Munich, Germany, 2013; p. 740. [Google Scholar]

- Morán, C.; Landero, R.; González, M.T. COPE-28: A psychometric analysis of the Spanish version of the Brief COPE. Univ. Psychol. 2009, 9, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.N.S.; Chan, C.S.; Ng, J.; Yip, C.-H. Action Type-Based Factorial Structure of Brief COPE among Hong Kong Chinese. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2016, 38, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhawaldeh, A.; Al Omari, O.; Al Aldawi, S.; Al Hashmi, I.; Ballad, C.A.; Ibrahim, A.; Al Sabei, S.; Alsaraireh, A.; Al Qadire, M.; Albashtawy, M. Stress Factors, Stress Levels, and Coping Mechanisms among University Students. Sci. World J. 2023, 2023, 2026971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedam, S.R.; Saklecha, P.P.; Babar, V. Screening of Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Coping, and Associated Factors Among Engineering Student. Ann. Indian Psychiatry 2020, 4, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Pu, C.; Waits, A.; Tran, T.D.; Balhara, Y.P.S.; Huynh, Q.T.V.; Huang, S.-L. Sources of stress, coping strategies and associated factors among Vietnamese first-year medical students. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ștefenel, D.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Rogobete, S.; Sassu, R. Coping Strategies and Life Satisfaction among Romanian Emerging Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillion, L.; Kovacs, A.H.; Gagnon, P.; Endler, N.S. Validation of the shortened cope for use with breast cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy. Curr. Psychol. 2002, 21, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.; Smith, H.; Brown, S.L. The brief COPE: A factorial structure for incarcerated adults. Crim. Justice Stud. 2021, 34, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isabel Mate, A.; Manuel Andreu, J.; Elena Pena, M. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Brief COPE Inventory (COPE-28) in a sample of teenagers. Behav. Psychol. 2016, 24, 305–318. [Google Scholar]

- Stoeber, J.; Janssen, D.P. Perfectionism and coping with daily failures: Positive reframing helps achieve satisfaction at the end of the day. Anxiety Stress. Coping 2011, 24, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-W. Learning motivations and effort beliefs in Confucian cultural context: A dual-mode theoretical framework of achievement goal. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1058456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Feng, M.; Yu, H.; Hou, Y. The Impact of the Chinese Thinking Style of Relations on Mental Health: The Mediating Role of Coping Styles. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.S.; Karlson, C.; Edmond, S.N.; Welkom, J.S.; Osunkwo, I.; Cohen, L.L. Emotion-Focused Avoidance Coping Mediates the Association Between Pain and Health-Related Quality of Life in Children With Sickle Cell Disease. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 41, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, B.C.H. Collectivism and coping: Current theories, evidence, and measurements of collective coping. Int. J. Psychol. 2012, 48, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, S.; Wheat, M.; Christensen, M.; Craft, J. Snaps+: Peer-to-peer and academic support in developing clinical skills excellence in under-graduate nursing students: An exploratory study. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 73, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ching, S.S.Y.; Cheung, K.; Hegney, D.; Rees, C.S. Stressors and coping of nursing students in clinical placement: A qualitative study contextualizing their resilience and burnout. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 42, 102690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Connor-Smith, J.K.; Saltzman, H.; Thomsen, A.H.; Wadsworth, M.E. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 87–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.Y.; Albarqouni, L.; von Eisenhart Rothe, A.F.; Hoschar, S.; Ronel, J.; Ladwig, K.H. Is denial a maladaptive coping mechanism which prolongs pre-hospital delay in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction? J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 91, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Jiang, T.; Li, H.; Hou, Y. Cultural Differences in Humor Perception, Usage, and Implications. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, W.; Deng, J.; Guo, W.; Chen, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, J. Spiritual Coping in Family Caregivers of Patients With Advanced Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2024, 67, e177–e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.-C.; Lee, H.-C.; Chu, T.-L.; Han, C.-Y.; Hsiao, Y.-C. A spiritual education course to enhance nursing students’ spiritual competencies. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 49, 102907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waugh, C.E.; Shing, E.Z.; Furr, R.M. Not all disengagement coping strategies are created equal: Positive distraction, but not avoidance, can be an adaptive coping strategy for chronic life stressors. Anxiety Stress. Coping 2020, 33, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, A.B.; Leary, M.R. Self-Compassion, Stress, and Coping. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2010, 4, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.M.; Orth, U. Acceptance as a Coping Reaction: Adaptive or not? Swiss J. Psychol. 2005, 64, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items of Brief-COPE | Factor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| C24 I’ve been learning to live with it. | 0.848 | |||||||

| C25 I’ve been thinking hard about what steps to take. | 0.802 | |||||||

| C2 I’ve been concentrating my efforts on doing something about the situation I’m in. | 0.688 | |||||||

| C7 I’ve been taking action to try to make the situation better. | 0.594 | |||||||

| C12 I’ve been trying to see it in a different light, to make it seem more positive. | 0.520 | |||||||

| C17 I’ve been looking for something good in what is happening. | 0.464 | |||||||

| C14 I’ve been trying to come up with a strategy about what to do. | 0.448 | |||||||

| C11 I’ve been using alcohol or other drugs to help me get through it. | 0.780 | |||||||

| C4 I’ve been using alcohol or other drugs to make myself feel better. | 0.753 | |||||||

| C22 I’ve been trying to find comfort in my religion or spiritual beliefs. | 0.541 | |||||||

| C16 I’ve been giving up the attempt to cope. | 0.540 | |||||||

| C23 I’ve been trying to get advice or help from other people about what to do. | 0.719 | |||||||

| C15 I’ve been getting comfort and understanding from someone. | 0.717 | |||||||

| C5 I’ve been getting emotional support from others. | 0.665 | |||||||

| C10 I’ve been getting help and advice from other people. | 0.447 | |||||||

| C13 I’ve been criticizing myself. | 0.753 | |||||||

| C26 I’ve been blaming myself for things that happened. | 0.631 | |||||||

| C21 I’ve been expressing my negative feelings. | 0.506 | |||||||

| C6 I’ve been giving up trying to deal with it. | 0.484 | |||||||

| C3 I’ve been saying to myself “this isn’t real”. | 0.732 | |||||||

| C28 I’ve been making fun of the situation. | 0.658 | |||||||

| C8 I’ve been refusing to believe that it has happened. | 0.572 | |||||||

| C27 I’ve been praying or meditating. | 0.546 | |||||||

| C18 I’ve been making jokes about it. | 0.507 | |||||||

| C1 I’ve been turning to work or other activities to take my mind off things. | 0.844 | |||||||

| C9 I’ve been saying things to let my unpleasant feelings escape. | 0.452 | |||||||

| C20 I’ve been accepting the reality of the fact that it has happened. | 0.844 | |||||||

| C19 I’ve been doing something to think about it less, such as going to movies, watching TV, reading, daydreaming, sleeping, or shopping. | 0.452 | |||||||

| Variance explained (%) | 12.09 | 10.54 | 8.39 | 7.39 | 6.44 | 5.01 | 4.92 | 4.84 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Item–Total Correlation | |

|---|---|---|

| The whole scale of Brief-COPE | 0.759 | 0.22–0.64 |

| The 8-factor structure | ||

| Factor 1 | 0.834 | 0.39–0.67 |

| Factor 2 | 0.711 | 0.25–0.55 |

| Factor 3 | 0.705 | 0.29–0.51 |

| Factor 4 | 0.717 | 0.36–0.41 |

| Factor 5 | 0.683 | 0.33–0.59 |

| Factor 6 | 0.721 | 0.29–0.38 |

| Factor 7 | 0.679 | 0.35–0.44 |

| Factor 8 | 0.622 | 0.24–0.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, C.; Wang, Q.; Bai, J. Factor Structure of the Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-COPE) in Chinese Nursing Students. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15020046

Cheng C, Wang Q, Bai J. Factor Structure of the Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-COPE) in Chinese Nursing Students. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(2):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15020046

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Cheng, Qingling Wang, and Jie Bai. 2025. "Factor Structure of the Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-COPE) in Chinese Nursing Students" Nursing Reports 15, no. 2: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15020046

APA StyleCheng, C., Wang, Q., & Bai, J. (2025). Factor Structure of the Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-COPE) in Chinese Nursing Students. Nursing Reports, 15(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15020046