Therapeutic Education for Safer Rheumatologic Care: A Scoping Review to Map Evidence on Infection Prevention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Research Question

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

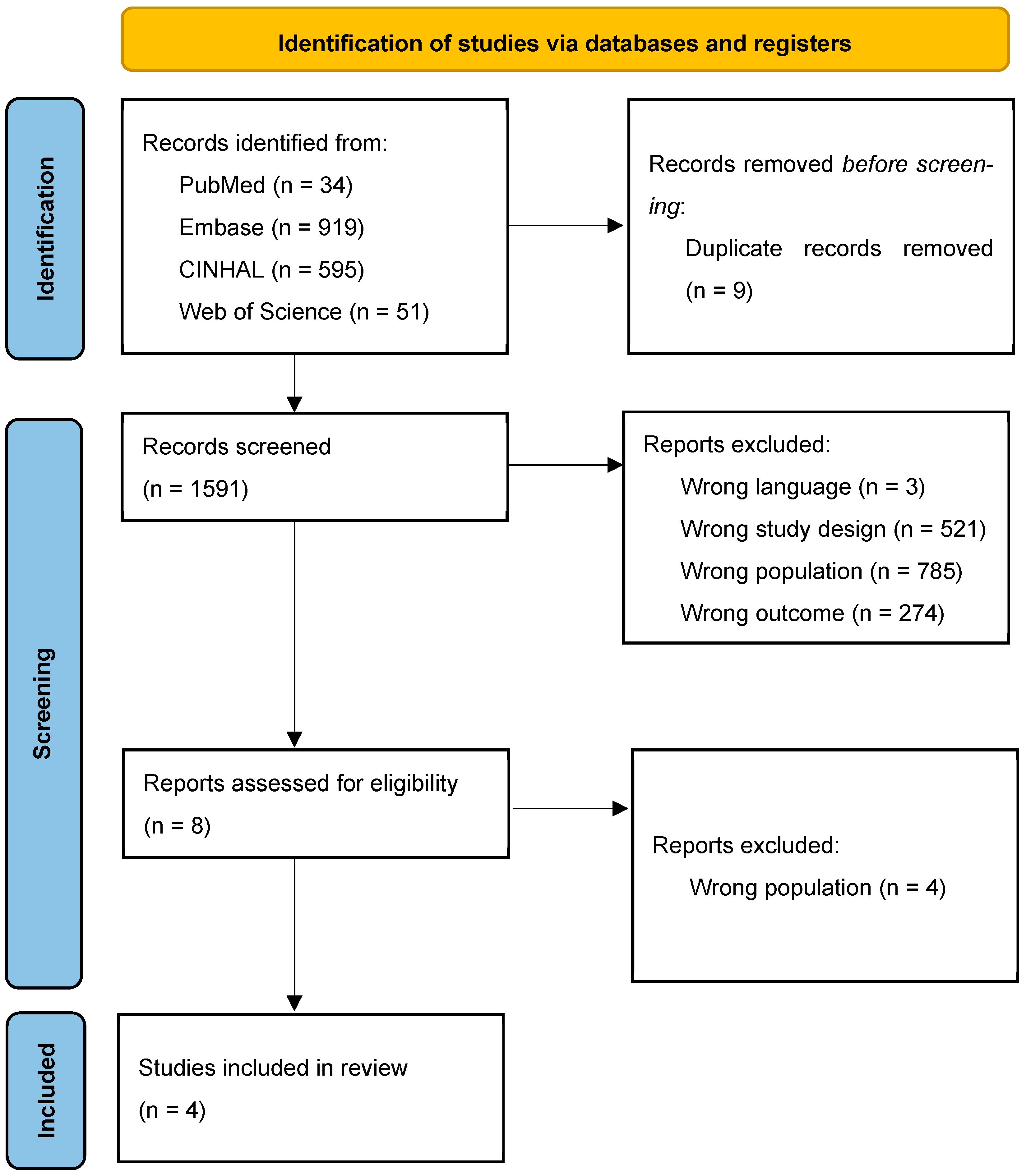

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Quality of Included Studies

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Educational Interventions and Outcomes in Infection Prevention Among Rheumatology Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Der Heijde, D.; Daikh, D.I.; Betteridge, N.; Burmester, G.R.; Hassett, A.L.; Matteson, E.L.; Van Vollenhoven, R.; Lakhanpal, S. Common language description of the term rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) for use in communication with the lay public, healthcare providers and other stakeholders endorsed by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 77, 829–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieza, A.; Causey, K.; Kamenov, K.; Hanson, S.W.; Chatterji, S.; Vos, T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 2006–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisetsky, D.S. Pathogenesis of autoimmune disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2023, 19, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Yip, L.; Wang, F.; Marty, S.-E.; Fathman, C.G. Autoimmune disease: Genetic susceptibility, environmental triggers, and immune dysregulation. Where can we develop therapies? Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1626082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewé, R.B.M.; Bergstra, S.A.; Kerschbaumer, A.; Sepriano, A.; Aletaha, D.; Caporali, R.; Edwards, C.J.; Hyrich, K.L.; Pope, J.E.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, M.; Ramos, M.R.R.; Kamal, S. Infection Risk in Biological Disease-Modifying Anti-rheumatic Drugs. Cureus 2025, 17, e80634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almoallim, H.; Cheikh, M. (Eds.) Skills in Rheumatology; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-15-8323-0 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Díaz-Lagares, C.; Pérez-Alvarez, R.; García-Hernández, F.J.; Ayala-Gutiérrez, M.M.; Callejas, J.L.; Martínez-Berriotxoa, A.; Rascón, J.; Caminal-Montero, L.; Selva-O’Callaghan, A.; Oristrell, J.; et al. Rates of, and risk factors for, severe infections in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases receiving biological agents off-label. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011, 13, R112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.A.; Cameron, C.; Noorbaloochi, S.; Cullis, T.; Tucker, M.; Christensen, R.; Ghogomu, E.T.; Coyle, D.; Clifford, T.; Tugwell, P.; et al. Risk of serious infection in biological treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2015, 386, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraenkel, L.; Bathon, J.M.; England, B.R.; St Clair, E.W.; Arayssi, T.; Carandang, K.; Deane, K.D.; Genovese, M.; Huston, K.K.; Kerr, G.; et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 73, 924–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furer, V.; Rondaan, C.; Heijstek, M.W.; Agmon-Levin, N.; Van Assen, S.; Bijl, M.; Breedveld, F.C.; D’Amelio, R.; Dougados, M.; Kapetanovic, M.C.; et al. 2019 update of EULAR recommendations for vaccination in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegeman, M.C.; Schoemaker-Delsing, J.A.; Luttikholt, J.T.M.; Vonkeman, H.E. Patient perspectives on how to improve education on medication side effects: Cross-sectional observational study at a rheumatology clinic in The Netherlands. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanam, S.; Ravindran, V. Education for patients with rheumatic diseases being treated with biologics: Need, strategies, challenges, and solutions. Clin. Rheumatol. 2025, 44, 533–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gossec, L.; Fautrel, B.; Flipon, É.; Lecoq d’André, F.; Marguerie, L.; Nataf, H.; Pallot Prades, B.; Piperno, M.; Poilverd, R.-M.; Rat, A.-C.; et al. Safety of biologics: Elaboration and validation of a questionnaire assessing patients’ self-care safety skills: The BioSecure questionnaire. An initiative of the French Rheumatology Society Therapeutic Education section. Jt. Bone Spine 2013, 80, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artime, E.; Kahlon, R.; Méndez, I.; Kou, T.; Garrido-Estepa, M.; Qizilbash, N. Linking process indicators and clinical/safety outcomes to assess the effectiveness of abatacept (ORENCIA) patient alert cards in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2020, 29, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiltz, U.; Celik, A.; Tsiami, S.; Buehring, B.; Baraliakos, X.; Andreica, I.; Kiefer, D.; Braun, J. Are patients with rheumatic diseases on immunosuppressive therapies protected against preventable infections? A cross-sectional cohort study. RMD Open 2021, 7, e001499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauvais, C.; Fayet, F.; Rousseau, A.; Sordet, C.; Pouplin, S.; Maugars, Y.; Poilverd, R.M.; Savel, C.; Ségard, V.; Godon, B.; et al. Efficacy of a nurse-led patient education intervention in promoting safety skills of patients with inflammatory arthritis treated with biologics: A multicentre randomised clinical trial. RMD Open 2022, 8, e001828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipps, S.; Paul, A.; Vasireddy, S. Incidence of COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic disease: Is prior health education more important than shielding advice during the pandemic? Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 1575–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Lin, Q.; Yu, B.; Hu, J. A systematic review of strategies in digital technologies for motivating adherence to chronic illness self-care. Npj Health Syst. 2025, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiphorou, E.; Santos, E.J.F.; Marques, A.; Böhm, P.; Bijlsma, J.W.; Daien, C.I.; Esbensen, B.A.; Ferreira, R.J.O.; Fragoulis, G.E.; Holmes, P.; et al. 2021 EULAR recommendations for the implementation of self-management strategies in patients with inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 1278–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zangi, H.A.; Ndosi, M.; Adams, J.; Andersen, L.; Bode, C.; Boström, C.; Van Eijk-Hustings, Y.; Gossec, L.; Korandová, J.; Mendes, G.; et al. EULAR recommendations for patient education for people with inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study ID | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Tot. of “YES” | Overall Appraisal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | Artime et al. (2020) [18] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 | No major concerns |

| Cross-sectional | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | Kiltz et al. (2021) [19] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Not available | 9 | Minor methodological concerns |

| Trials | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | Beauvais et al. (2022) [20] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not available | 10 | No major concerns |

| 4 | Kipps et al. (2020) [21] | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Yes | No | Not available | 5 | Several methodological limitations |

| Author, Year and Country of Publication | Aim of the Study | Study Design | Study Population and Sample Size | Age | Female (%) | Interdisciplinary Team (Healthcare Providers) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artime E et al., 2020 [18], Five European countries (Spain, United Kingdom, Germany, France, Sweden) | To evaluate the effectiveness of Patient Alert Cards (PACs) for the drug abatacept (ORENCIA) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis by comparing process indicators and clinical and safety outcomes. | Multicenter study consisting of a cross-sectional survey and a retrospective review of medical records. | 190 patients. | 26–35 years, 6 pts (3.16%); 36–45 years, 21 pts (11.05%); 46–55 years, 29 pts (15.26%); 56–65 years, 55 pts (28.95%); >65 years, 79 pts (41.58%). | 146 pts (76.84%) | Rheumatologists and nurses participated in the study. |

| Beauvais C et al., 2022 [20], France | To evaluate the effect of nurse-led patient education on safety competencies in patients with inflammatory arthritis (IA) treated with bDMARDs. | Multicenter randomized controlled trial | 127 patients with rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis—Group Standard 64, Control Group 63 | GC 45.4 ± 13.0; GS 48.6 ± 12.6 | GC = 69.8%; GS = 62.5% | Rheumatologists and nurses |

| Kiltz U et al., 2021 [19], Germany | To evaluate the prevalence of infection, hospitalization due to infections, vaccination status, and infection screening before starting bDMARDs in a cohort of patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases (CIRD) who received an informative intervention about vaccination strategies. | Single-center cross-sectional study | Population: patients with CIRD; total 975 patients (173 immigrants, 424 with rheumatoid arthritis, 132 with psoriatic arthritis, 145 with axial spondyloarthritis, 41 with SLE); number on bDMARDs = 499 | Mean age (±SD): 55.3 ± 15.5 (range 18–90 years) | Female %: RA 67.7%, axSpA 34.5%, PsA 58.4%, SLE 90.6%, Other Diseases 72.6% | Patients most commonly received vaccination information from general practitioners (79%), with rheumatologists providing it less frequently (34%). Other specialists (5%) and public healthcare staff (4%) played minor roles. Overall, 141 patients reported receiving information from multiple healthcare providers. |

| Kipps S. et al., 2020 [21], United Kingdom | Application of a guide for the rheumatology team to better stratify patients by infection risk, followed by a letter with effective protection and prevention measures against COVID-19 infection. | Cohort of rheumatologic patients receiving DMARDs, biologics, JAK inhibitors, or corticosteroids was stratified by infection risk. Patients with a risk score ≥ 3 (range 0–6) were notified by letter about their risk status and advised to adopt preventive measures against SARS-CoV-2. | Cohort of 887 patients, of whom 248 had a risk score ≥ 3 and received the informational letter on COVID-19 infection risk mitigation. | In the group receiving the letter (risk score ≥ 3), age ≥ 70 years | N.A. | Rheumatology teams (specific healthcare professionals not detailed). |

| Author, Year and Country of Publication | Key Findings | Outcome Measures Included | Patient Education Intervention (If Applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artime E et al., 2020 [18], five European countries (Spain, UK, Germany, France, Sweden). | A statistically significant association was observed between the overall composite score and tuberculosis screening: overall scores ≥ 67%, 34–67%, and ≤33% were associated with TB screening rates of 60.0%, 81.0%, and 54.2%, respectively (p = 0.004). No significant correlation was found for viral hepatitis screening (scores ≥ 67%, 34–67%, ≤33% associated with screening rates of 57.5%, 70.7%, and 56.6%, p = 0.206). Hospitalization rates for infections increased as patient survey scores decreased: 2.5%, 5.2%, and 8.4%, respectively (p = 0.44). No significant correlation was found between questionnaire scores and ER visits or mean time to seek medical care. | Percentage of patients screened for tuberculosis (TB) and viral hepatitis (VH) before treatment; correlation between screening and global patient questionnaire score; percentage of patients with serious infections causing hospitalization or ER visits; mean time between symptom onset and seeking care. | Patient Alert Cards (PACs) provided and explained to patients to raise awareness about infection risks and side effects related to abatacept treatment. |

| Beauvais C et al., 2022 [20], France | Nurse-led patient education positively impacted safety behaviors in bDMARDs-treated patients; mean biosecure score at 6 months was 81.2 ± 13.1 in the intervention group vs. 75.5 ± 13 in control (difference 5.6, p = 0.016), showing improved safety behaviors. Secondary outcomes showed no significant differences except for coping (p < 0.03). | AHI (Arthritis Helplessness Index), ASAS, ASDAS, BASDAI, BMQ, DAS28. | Face-to-face patient education sessions at baseline and 3 months focused on safety behaviors and self-injections per French Rheumatology Society guidelines; sessions preceded by individual nurse assessment; supported by booklet; session duration ~65 min at baseline and 44 min at 3 months; both groups continued standard clinical care including medication info from rheumatologists. |

| Kiltz U et al., 2021 [19], Germany | Patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases (CIRDs) remain insufficiently protected against vaccine-preventable infections: 7.6% of those vaccinated against measles lacked protective antibody titers. All patients receiving bDMARDs were screened for latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) and hepatitis B, revealing LTBI in 16 individuals; among HBV-positive patients, 33.4% received prophylaxis and 64.3% showed protective immunity. Only 55.4% presented vaccination records. Although 64.5% (n = 629) had received education on vaccination strategies, adherence remained poor (p = 0.200). Despite the availability of professional vaccination counseling, overall vaccination coverage was low-to-moderate. Infection risk (RABBIT Risk Score) did not correlate with vaccination score, but increased age and longer disease duration were associated with higher risk, while low vaccination status correlated with higher disease activity and immigrant background. | Physical function (HAQ, BASFI), Infection risk (RABBIT Risk Score), infection screening, immunization score. | Vaccination information available only via paper-based vaccination cards; no structured educational intervention detailed. |

| Kipps S. et al., 2020 [21], United Kingdom | Only one patient tested positive for COVID-19 in the high-risk group that received an informational letter, showing infection rates similar to the general population. No evidence that the letter reduced COVID-19 incidence due to lack of control group. COVID-19 incidence was similar between letter group (0.403%) and UK population (0.397%). Trend toward lower incidence (0.113%) observed in the entire cohort. | COVID-19 incidence rates, infection risk assessed via BSR risk stratification guidance. | Informational letter sent to patients with risk score ≥ 3 advising on protective and preventive measures against COVID-19 infection. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El Aoufy, K.; Magi, C.E.; Melis, M.R.; Caffarri, C.; Civile, G.; Daffini, E.; Loss, E.; Ortis, H.; Rinaldi, A.; Zonca, C.; et al. Therapeutic Education for Safer Rheumatologic Care: A Scoping Review to Map Evidence on Infection Prevention. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120431

El Aoufy K, Magi CE, Melis MR, Caffarri C, Civile G, Daffini E, Loss E, Ortis H, Rinaldi A, Zonca C, et al. Therapeutic Education for Safer Rheumatologic Care: A Scoping Review to Map Evidence on Infection Prevention. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(12):431. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120431

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl Aoufy, Khadija, Camilla Elena Magi, Maria Ramona Melis, Cristiana Caffarri, Giovanni Civile, Elena Daffini, Eleonora Loss, Helena Ortis, Antonella Rinaldi, Claudia Zonca, and et al. 2025. "Therapeutic Education for Safer Rheumatologic Care: A Scoping Review to Map Evidence on Infection Prevention" Nursing Reports 15, no. 12: 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120431

APA StyleEl Aoufy, K., Magi, C. E., Melis, M. R., Caffarri, C., Civile, G., Daffini, E., Loss, E., Ortis, H., Rinaldi, A., Zonca, C., Bambi, S., & Rasero, L. (2025). Therapeutic Education for Safer Rheumatologic Care: A Scoping Review to Map Evidence on Infection Prevention. Nursing Reports, 15(12), 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120431