Biopsychosocial and Occupational Health of Emergency Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

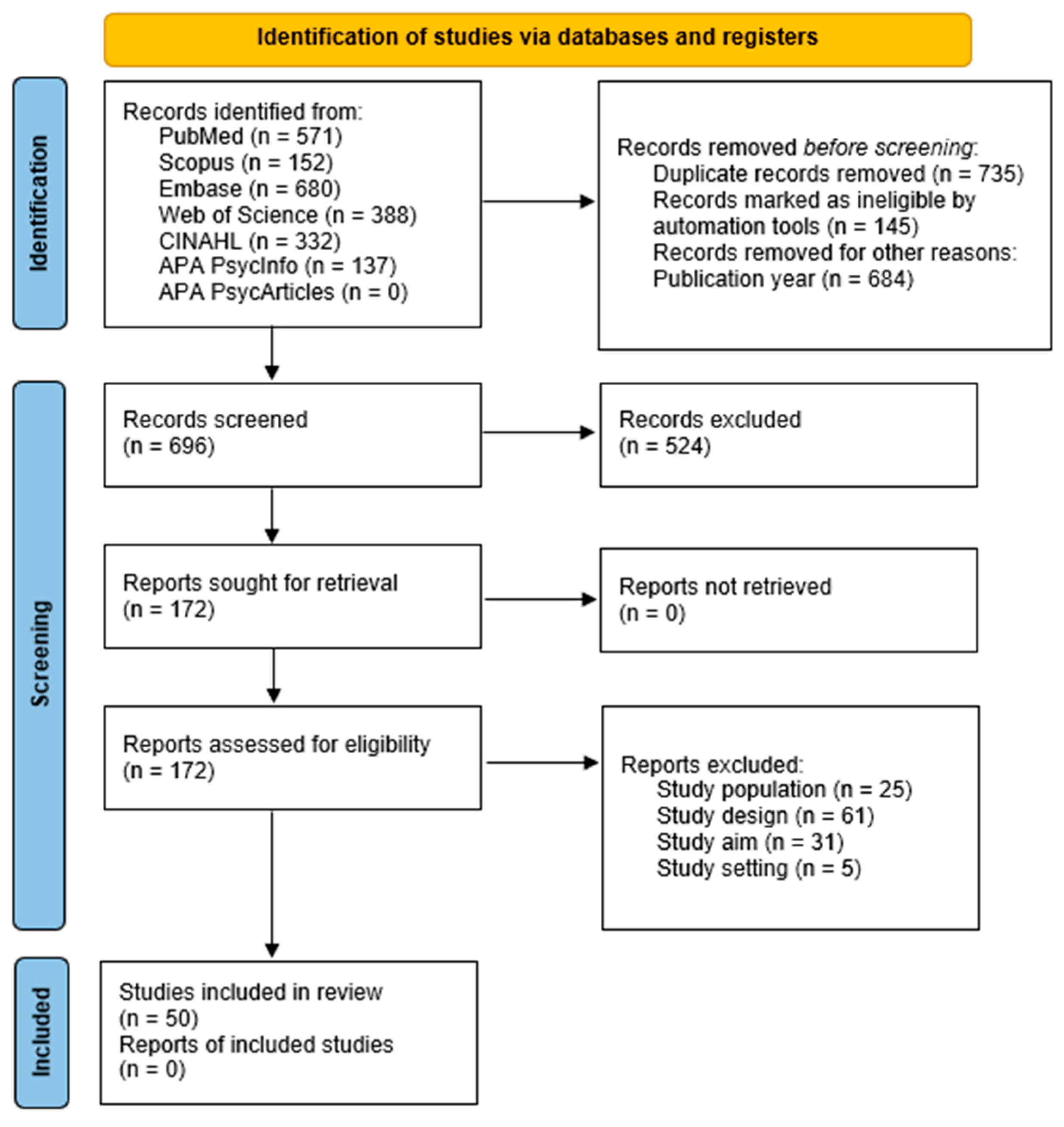

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Collection and Extraction

2.5. Data Meta-Analysis and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Characteristics of Participants

3.3. Biopsychosocial Health of Emergency Workers

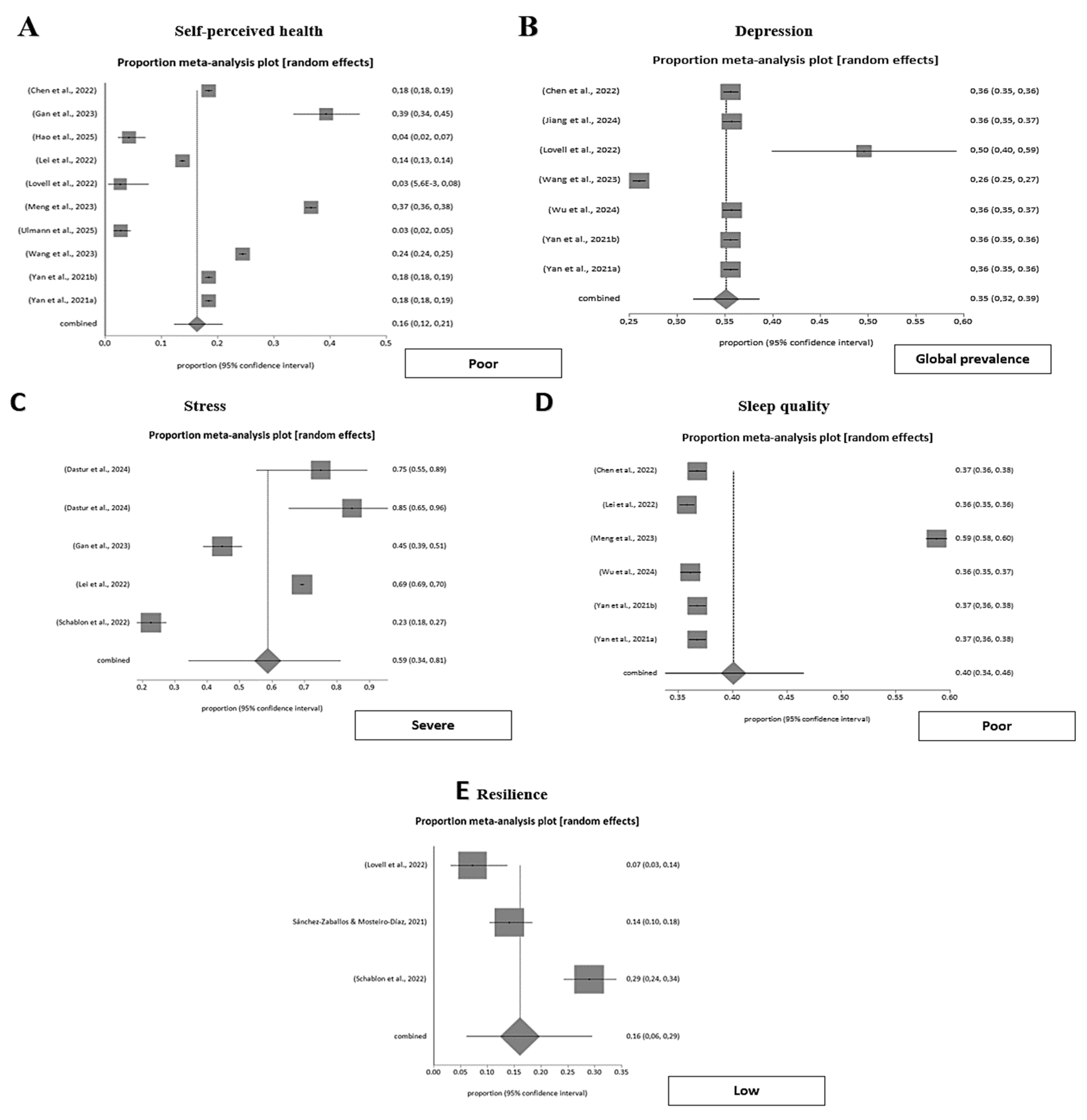

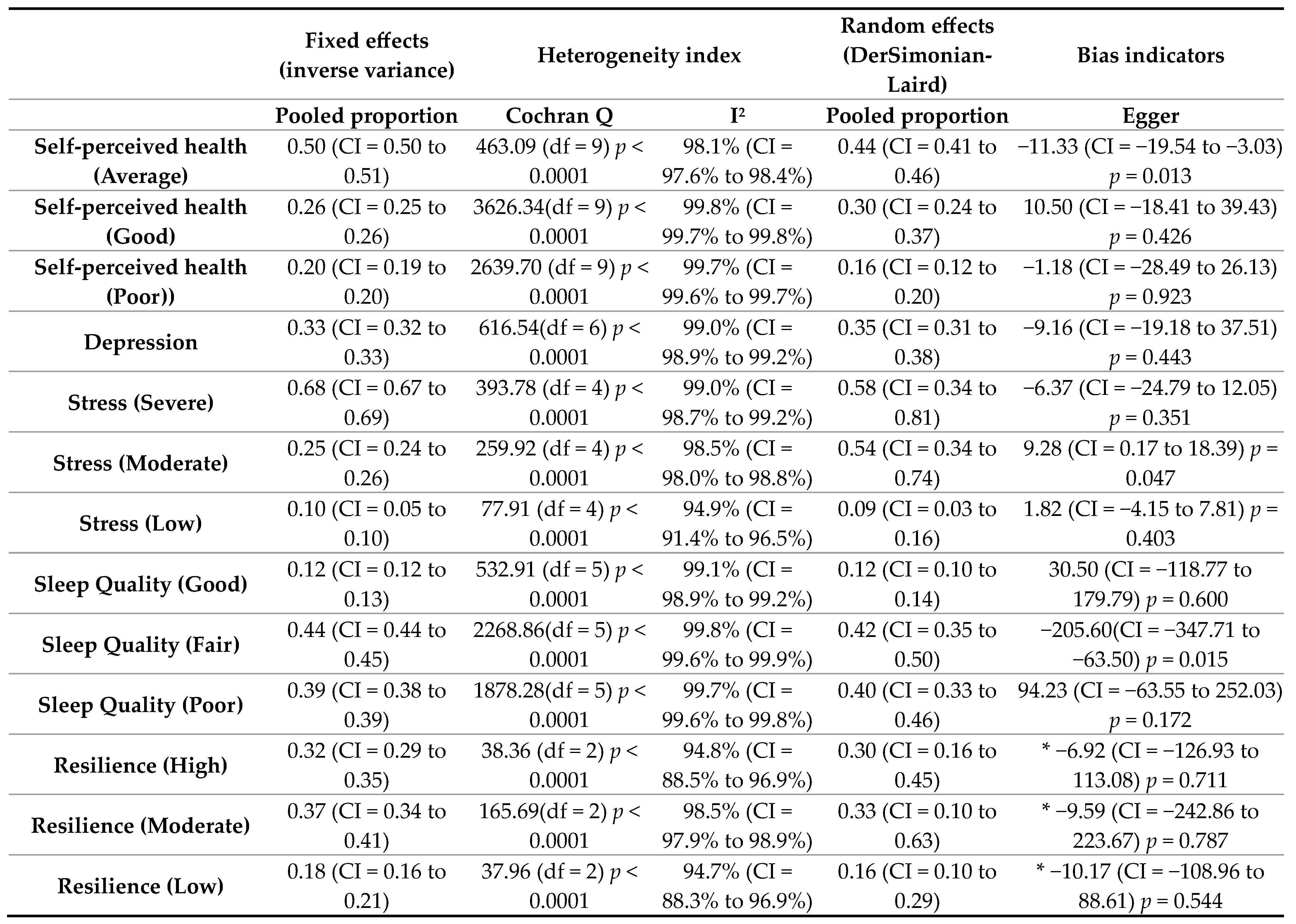

3.3.1. Self-Perceived Health of Emergency Workers

Factors Related to Self-Perceived Health of Emergency Workers

3.3.2. Depression of Emergency Workers

3.3.3. Stress of Emergency Workers

3.3.4. Sleep Quality of Emergency Workers

3.3.5. Resilience of Emergency Workers

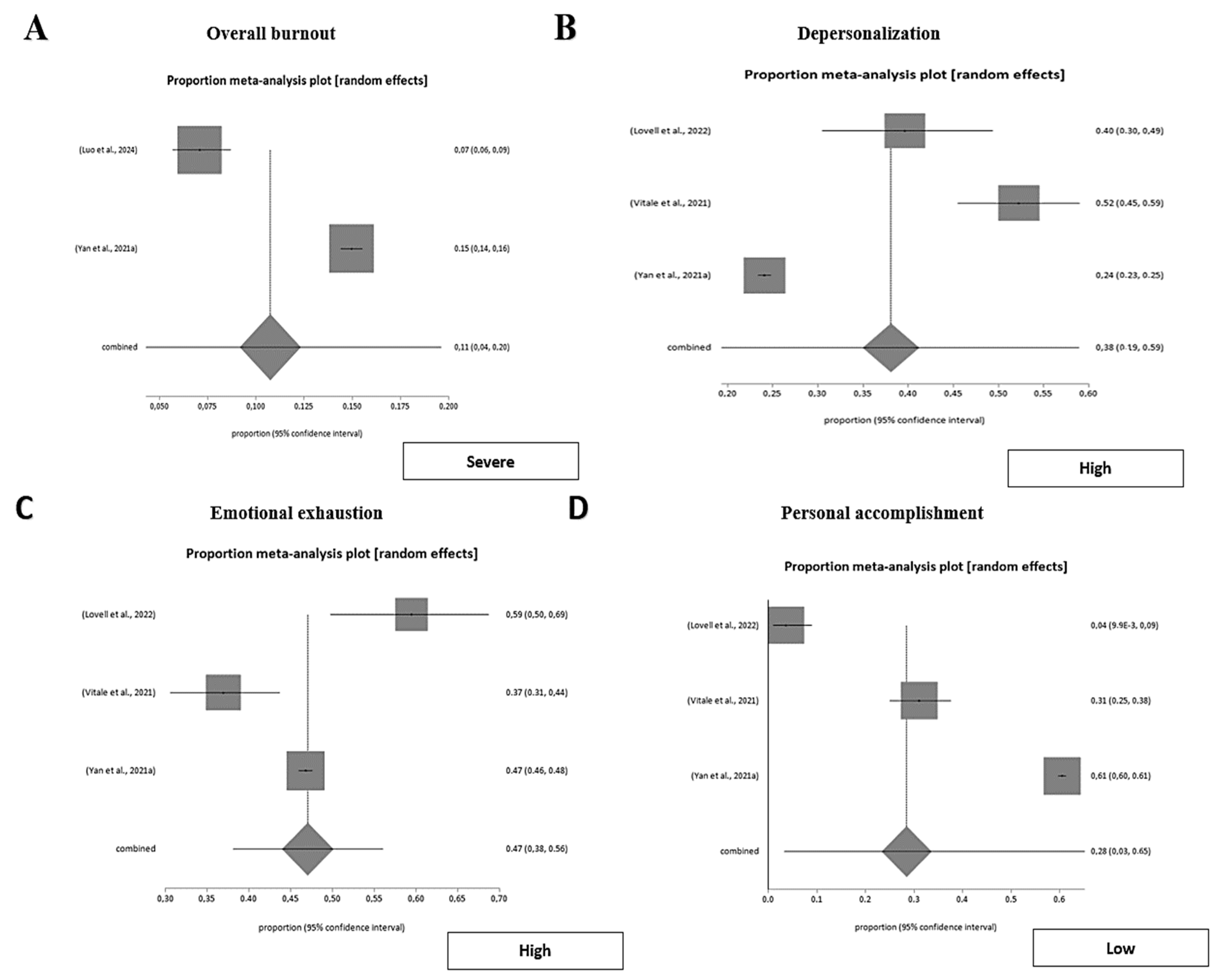

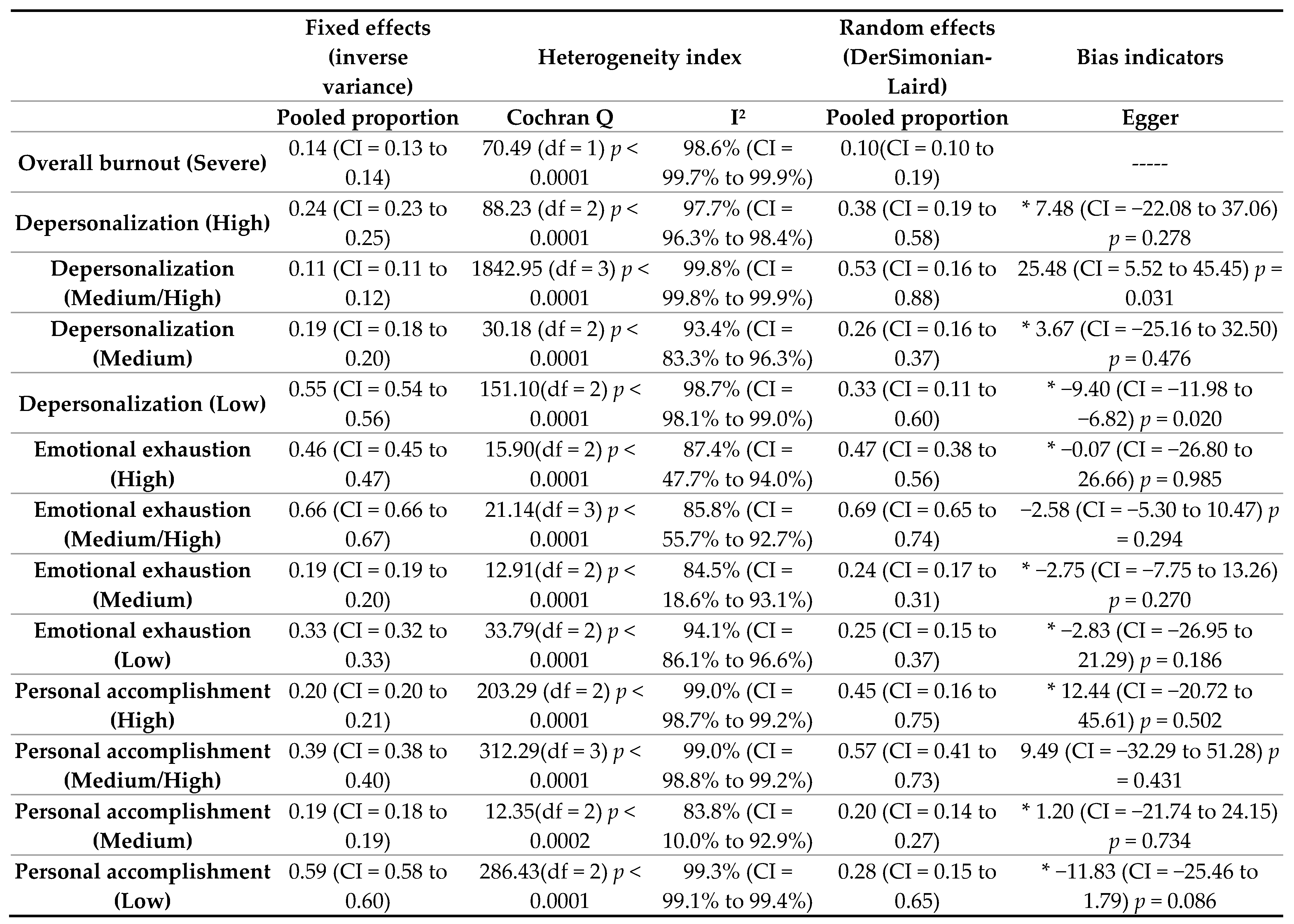

3.3.6. Burnout of Emergency Workers

Emotional Exhaustion of Emergency Workers

Depersonalization of Emergency Workers

Personal Accomplishment of Emergency Workers

Interventions for Decreasing Burnout of Emergency Workers

3.4. Work Health of Emergency Workers

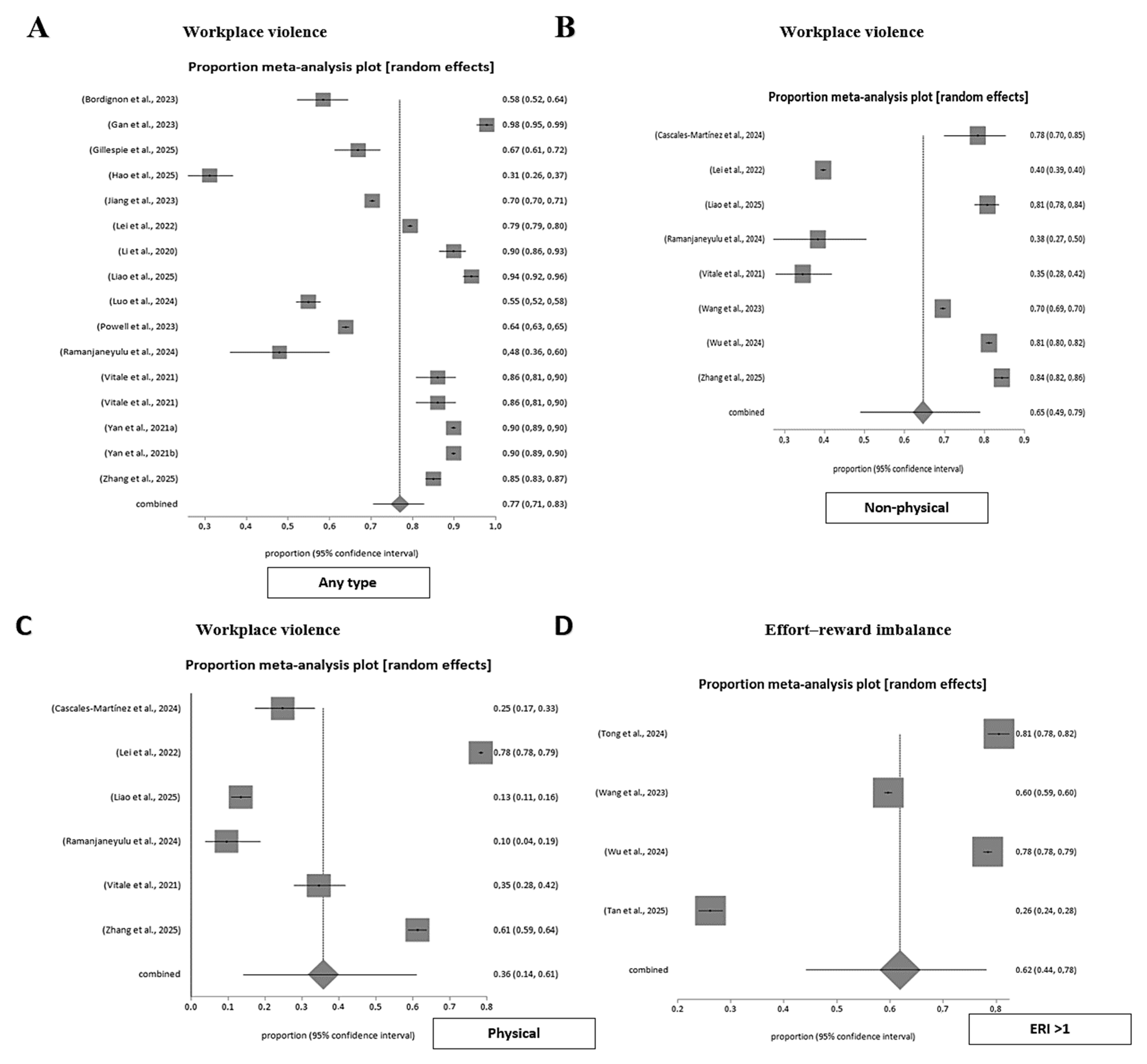

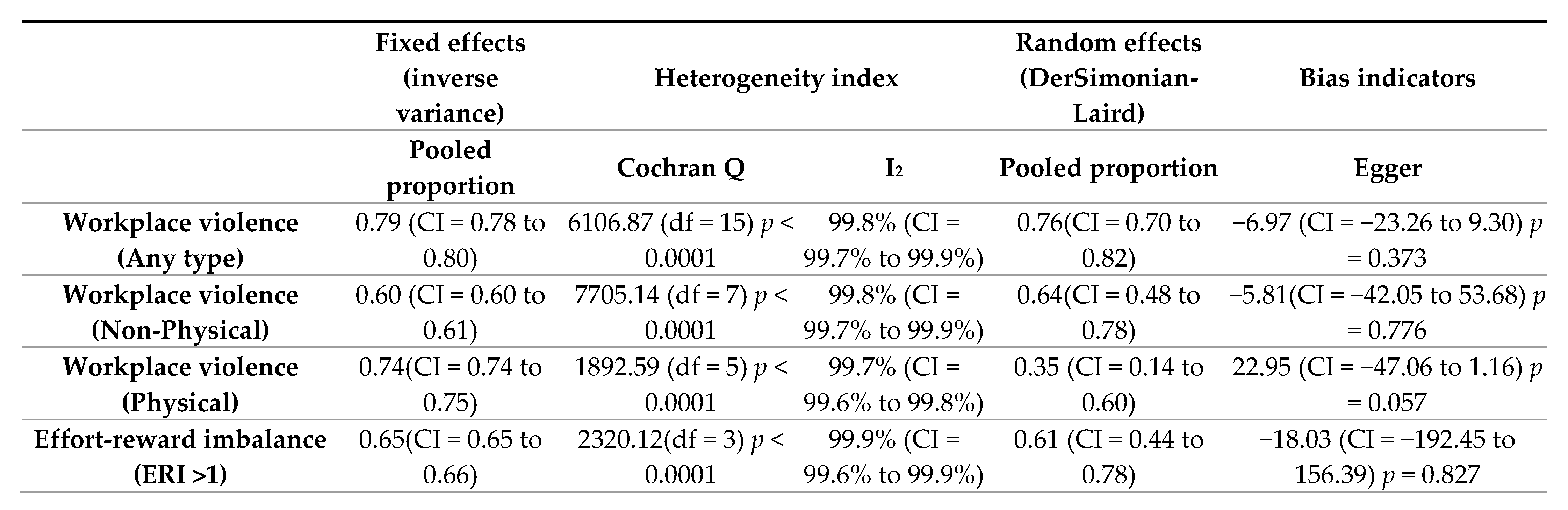

3.4.1. Workplace Violence in Emergency Departments

Factors Related to Workplace Violence in Emergency Departments

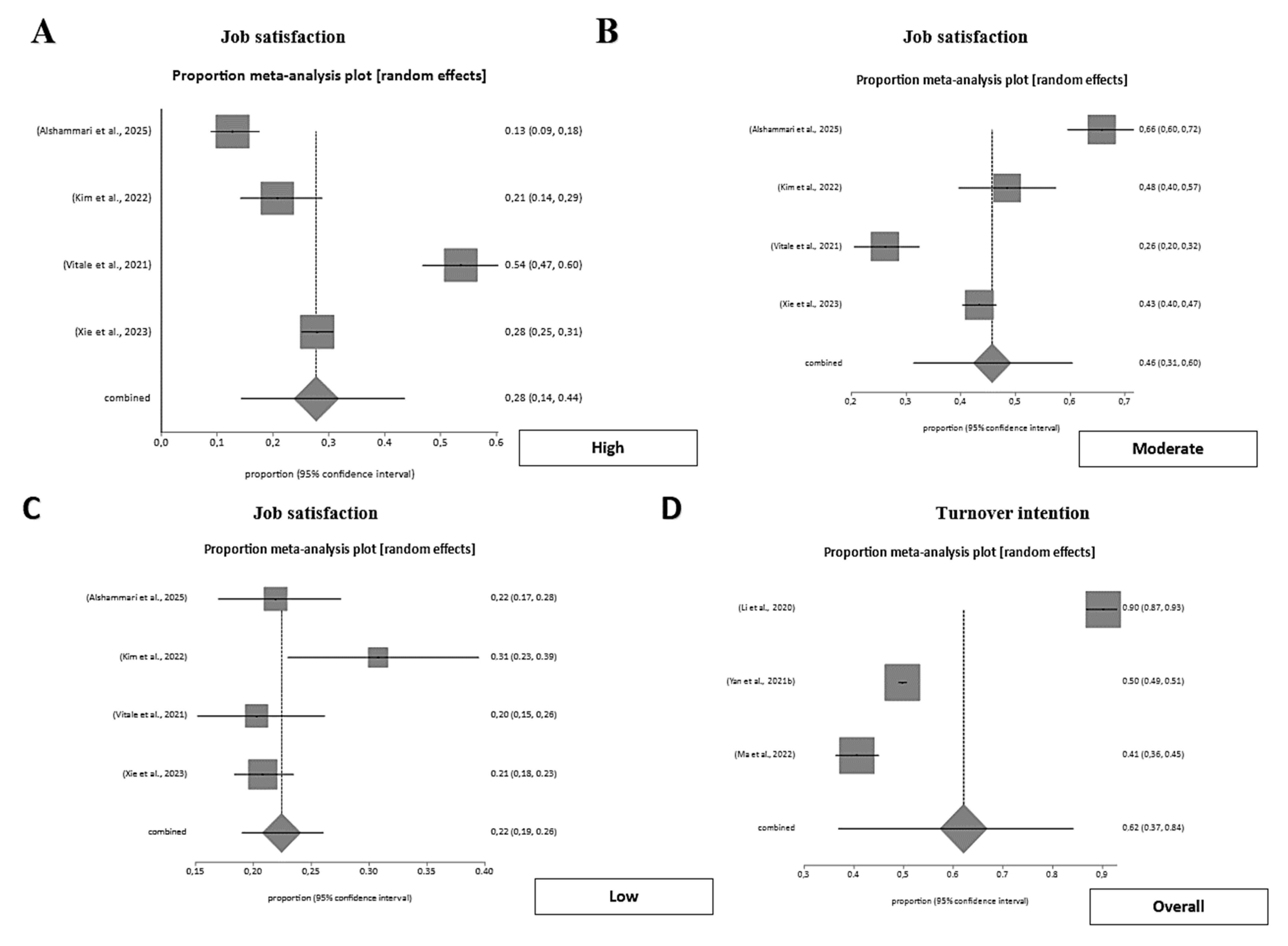

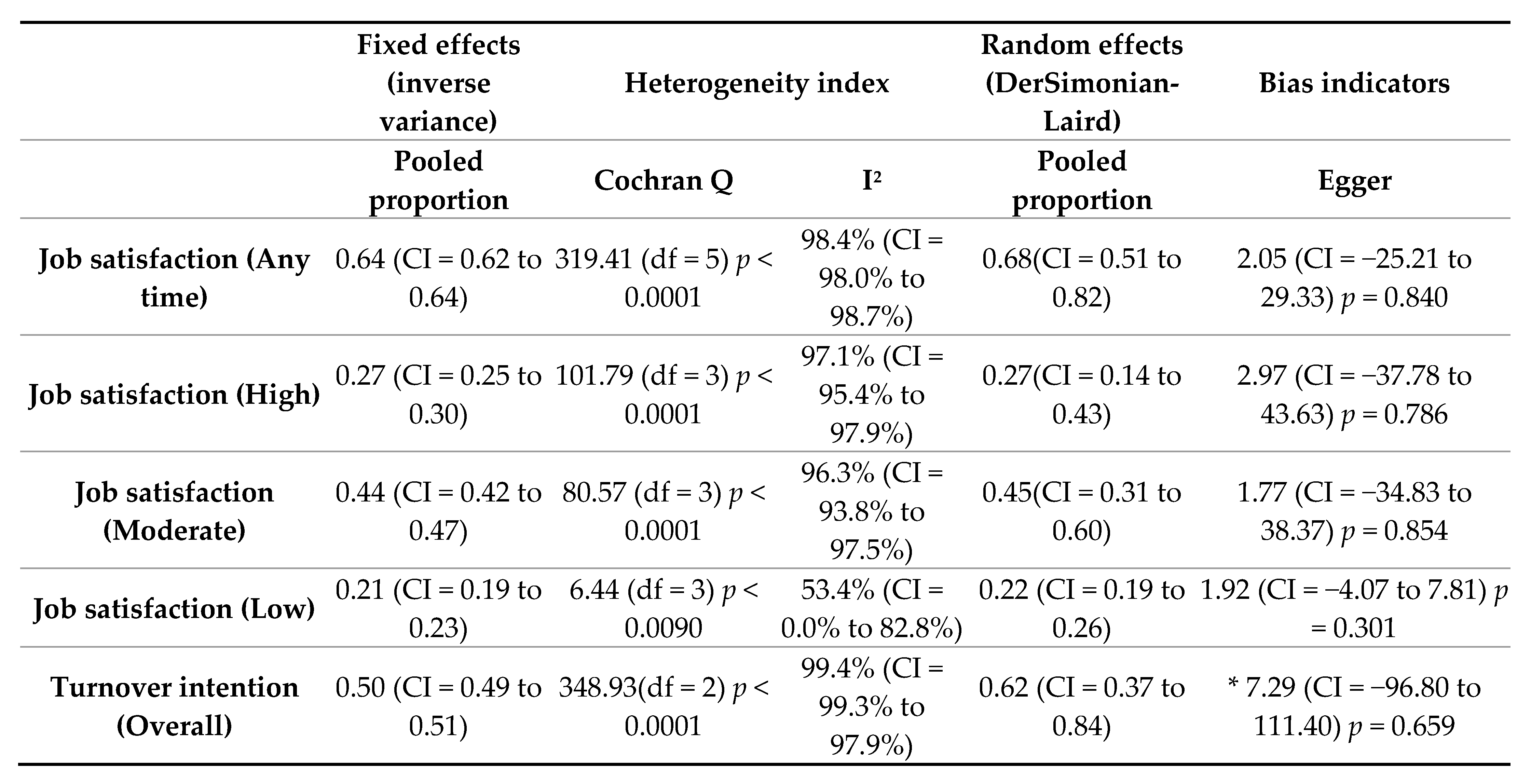

3.4.2. Job Satisfaction of Emergency Workers

Factors Related to Job Satisfaction of Emergency Workers

3.4.3. Effort-Reward Imbalance in Emergency Workers

3.4.4. Work Engagement of Emergency Workers

3.4.5. Turnover Intention of Emergency Workers

4. Discussion

4.1. Biopsychosocial Health Outcomes

4.2. Work Health Outcomes

4.3. Integration of Biopsychosocial and Occupational Dimensions

4.4. Limitations and Strengths of the Review

4.5. Nursing Clinical and Research Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APA | American Psychological Association. |

| CBI | Copenhagen Burnout Inventory. |

| CI | Confidence Interval. |

| ED | Emergency Department. |

| ERI | Effort-Reward Imbalance. |

| GHQ-28 | General Health Questionnaire—28 items. |

| HABS-U/HABS-CS | Hospital Aggressive Behaviour Scale—Users/Coworkers and Superiors. |

| I2 | Between-study heterogeneity index (I-squared). |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute. |

| κ (Kappa) | Inter-rater agreement coefficient. |

| MBI/MBI-GS | Maslach Burnout Inventory/General Survey. |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings. |

| MSQ | Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. |

| n/A | Not Applicable. |

| n | Sample size. |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire—9 items. |

| PIO | Person, Intervention, and Outcomes framework. |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. |

| QNWL | Quality of Nursing Work Life. |

| RS-13 | Resilience Scale—13 items. |

| UWES/UWES-9 | Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (9 items). |

| WAI | Work Ability Index. |

| WFCS/WFBRC-S | Work-Family Conflict Scale/Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict Scale. |

| WHO | World Health Organization. |

| WPVB | Workplace Psychologically Violent Behaviors instrument. |

| χ2 (Chi-square) | Chi-square test statistic. |

| ε2 (Eta-squared) | Effect size (Eta-squared). |

| p | Statistical significance level. |

| M/SD/IQR | Mean/Standard Deviation/Interquartile Range. |

References

- World Health Organization. Summary Report on Proceedings, Minutes and Final Acts of the International Health Conference Held in New York from 19 June to 22 July 1946; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1948; ISBN 978-92-4-160002-6. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, M.; Knottnerus, J.A.; Green, L.; van der Horst, H.; Jadad, A.R.; Kromhout, D.; Leonard, B.; Lorig, K.; Loureiro, M.I.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; et al. How Should We Define Health? BMJ 2011, 343, d4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsten, W. The Evolution from Occupational Health to Healthy Workplaces. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2024, 18, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on the Future of Nursing 2020–2030; Flaubert, J.L.; Menestrel, S.L.; Williams, D.R.; Wakefield, M.K. Supporting the Health and Professional Well-Being of Nurses. In The Future of Nursing 2020–2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Timbol, C.R.; Baraniuk, J.N. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome in the Emergency Department. Open Access Emerg. Med. 2019, 11, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, G.; Salyers, M.P.; Rollins, A.L.; Monroe-DeVita, M.; Pfahler, C. Burnout in Mental Health Services: A Review of the Problem and Its Remediation. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2012, 39, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Firtko, A.; Edenborough, M. Personal Resilience as a Strategy for Surviving and Thriving in the Face of Workplace Adversity: A Literature Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The Measurement of Experienced Burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, D.; Koutelekos, I.; Evangelou, E.; Dousis, E.; Mangoulia, P.; Gerogianni, G.; Zartaloudi, A.; Toulia, G.; Kelesi, M.; Margari, N.; et al. Investigation of Nurses’ Wellbeing towards Errors in Clinical Practice—The Role of Resilience. Medicina 2023, 59, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; De La Fuente-Solana, E.I.; Albendín-García, L.; Vargas-Pecino, C.; Ortega-Campos, E.M.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome in Emergency Nurses: A Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care Nurse 2017, 37, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Salgado, J.; Domínguez-Salas, S.; Romero-Martín, M.; Romero, A.; Coronado-Vázquez, V.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Work Engagement and Psychological Distress of Health Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 6.5.; Cochrane Database: London, UK, 2024; Available online: www.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews That Include Randomised or Non-Randomised Studies of Healthcare Interventions, or Both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI. 2025 JBI Critical Appraisal Tools. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Tawfik, G.M.; Dila, K.A.S.; Mohamed, M.Y.F.; Tam, D.N.H.; Kien, N.D.; Ahmed, A.M.; Huy, N.T. A Step by Step Guide for Conducting a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Simulation Data. Trop. Med. Health 2019, 47, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelly, A.C.; Dettori, J.R.; Brodt, E.D. Assessing Bias: The Importance of Considering Confounding. Evid. Based Spine Care J. 2012, 3, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Guyatt, G. Fixed-Effect and Random-Effects Models in Meta-Analysis. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, G.; Rücker, G. Meta-Analysis of Proportions. In Meta-Research: Methods and Protocols; Evangelou, E., Veroniki, A.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 159–172. ISBN 978-1-0716-1566-9. [Google Scholar]

- von Hippel, P.T. The Heterogeneity Statistic I2 Can Be Biased in Small Meta-Analyses. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancerlioglu, S.; Konakci, G.; Ozturk, S.; Kiyan, G.S. Does Workplace Violence Reduce Job Satisfaction Levels of Emergency Service Workers? Int. J. Caring Sci. 2020, 13, 2082–2087. [Google Scholar]

- Dastur, S.; Zandi, M.; Karimian, M. The Effect of Virtual Self-Management Training in Communication Skills on The Level of Violence and Occupational Stress of Emergency Technicians at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in 2021. J. Health Saf. Work. 2024, 14, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines-Stellisch, K.; Gawlik, K.S.; Teall, A.M.; Tucker, S. Implementation of Coaching to Address Burnout in Emergency Clinicians. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2024, 50, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Chen, H.; Yin, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Tian, M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wu, J.; Lv, C.; et al. Comparison of Depressive Symptoms among Emergency Physicians and the General Population in China: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on National Data. Hum. Resour. Health 2024, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.M.D.; Gensimore, M.M.; Maduro, R.S.; Morgan, M.K.; Zimbro, K.S. The Impact of Burnout on Emergency Nurses’ Intent to Leave: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2021, 47, 892–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Yan, S.; Jiang, H.; Feng, J.; Han, S.; Herath, C.; Shen, X.; Min, R.; Lv, C.; Gan, Y. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Workplace Violence against Emergency Department Nurses in China. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shen, X.; Feng, J.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, W.; Song, X.; Lv, C. Prevalence and Predictors of Depression among Emergency Physicians: A National Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Jiang, N.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, F.; Fu, W.; Yin, X. How Work-Family Conflict Influences Emergency Department Nurses’ Turnover Intention: The Mediating Role of Positive and Negative Affect. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2023, 68, 101289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Gu, M.; Sok, S. Relationships between Violence Experience, Resilience, and the Nursing Performance of Emergency Room Nurses in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-Y.; Kim, H.; Park, K.-H. Experience of Violence and Factors Influencing Response to Violence Among Emergency Nurses in South Korea: Perspectives on Stress-Coping Theory. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2022, 48, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, F.; Jiang, Y. Connor Davidson Resilience Scores, Perceived Organizational Support and Workplace Violence among Emergency Nurses. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2024, 75, 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, F.; Xing, D.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, Y. Study on the Associated Factors of Turnover Intention among Emergency Nurses in China and the Relationship between Major Factors. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2022, 60, 101106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Dai, Y.; Jia, S.; Liu, S.; Zhao, C.; Liu, X. Latent Profile Analysis of Mental Workload among Emergency Department Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanjaneyulu, E.; Kumar, B.S.; Rao, B.V.; Kumar, M.V.K. Safety Attitudes and Workplace Violence Among Emergency Room Doctors: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Med. Public Health 2024, 14, 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Atta, M.H.R.; Elsayed, S.M.; El-Gazar, H.E.; Abdelhafez, N.G.E.; Zoromba, M.A. Role of Violence Exposure on Altruistic Behavior and Grit among Emergency Nurses in Rural Hospitals. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2025, 72, e13086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kousha, S.; Shahrami, A.; Forouzanfar, M.M.; Sanaie, N.; Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F.; Skerrett, V. Effectiveness of Educational Intervention and Cognitive Rehearsal on Perceived Incivility among Emergency Nurses: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J. Linking Toxic Leadership with Work Satisfaction and Psychological Distress in Emergency Nurses: The Mediating Role of Work-Family Conflict. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2024, 50, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulmann, R.; Zeller, A.; Hirt, J. Self-rated health of emergency nurses-a cross-sectional study. Notf. Rettungsmedizin 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, D.; Višnjić, A. Mobbing and Violence at Work as Hidden Stressors and Work Ability Among Emergency Medical Doctors in Serbia. Medicina 2020, 56, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Liu, M.; Okoli, C.T.C.; Zeng, L.; Huang, S.; Ye, X.; Liu, F.; Wang, J. Construction and Evaluation of a Predictive Model for Compassion Fatigue among Emergency Department Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 148, 104613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Shen, X.; Wang, R.; Luo, Z.; Han, X.; Gan, Y.; Lv, C. The Prevalence of Turnover Intention and Influencing Factors among Emergency Physicians: A National Observation. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Shen, X.; Wang, R.; Luo, Z.; Han, X.; Gan, Y.; Lv, C. Challenges Faced by Emergency Physicians in China: An Observation from the Perspective of Burnout. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovell, L.-M.P.; Atherley, A.E.N.; Watson, H.R.; King, R.D. An Exploration of Burnout and Resilience among Emergency Physicians at Three Teaching Hospitals in the English-Speaking Caribbean: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Lancet Reg. Health–Am. 2022, 15, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, N.; Gong, Y.; Ye, F.; Li, J.; Zhou, P.; Yin, X. Occurrence and Correlated Factors of Physical and Verbal Violence among Emergency Physicians in China. J. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 04013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Q.-W.; Yu, R.; Lian, Z.-R.; Yuan, Y.-L.; Li, Y.-P.; Zheng, L.-L. Relationship between Nightmare Distress and Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Emergency Department Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. World J. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Mu, K.; Gong, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, N.; Zhang, G.; Lv, C.; Yin, X. Occurrence of Self-perceived Medical Errors and Its Related Influencing Factors among Emergency Department Nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Gong, Y.; Luo, J.; Yin, X. Prevalence of Occupational Injury and Its Associated Factors among Emergency Department Physicians in China: A Large Sample, Cross-Sectional Study. Prev. Med. 2024, 180, 107878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schablon, A.; Kersten, J.F.; Nienhaus, A.; Kottkamp, H.W.; Schnieder, W.; Ullrich, G.; Schäfer, K.; Ritzenhöfer, L.; Peters, C.; Wirth, T. Risk of Burnout among Emergency Department Staff as a Result of Violence and Aggression from Patients and Their Relatives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Zaballos, M.; Mosteiro-Díaz, M.P. Resilience Among Professional Health Workers in Emergency Services. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2021, 47, 925–932.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmus, P.; Marcinkowska, W.; Cieleban, N.; Lipert, A. Workload and coping with stress and the health status of emergency medical staff in the context of work-life balance. Med. Pract. 2020, 71, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L. Effects of Long-Term Noise Exposure on Mental Health and Sleep Quality of Emergency Medical Staff and Coping Strategies. Noise Health 2025, 27, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Zhou, X.; Gong, Y.; Tian, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.; Yin, X.; et al. Factors Related to Turnover Intention among Emergency Department Nurses in China: A Nationwide Cross-sectional Study. Nurs. Crit. Care 2023, 28, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhong, L.; Zhu, L.; Chen, X. Relationship between Workplace Violence and Occupational Health in Emergency Nurses: The Mediating Role of Dyssomnia. Nurs. Crit. Care 2025, 30, e70008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascales-Martínez, A.; López-Ros, P.; Pina, D.; Cánovas-Pallares, J.M.; López López, R.; Puente-López, E.; Piserra Bolaños, C. Differences in Workplace Violence and Health Variables among Professionals in a Hospital Emergency Department: A Descriptive-Comparative Study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0314932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Song, M.R. Effects of Emergency Nurses’ Experiences of Violence, Resilience, and Nursing Work Environment on Turnover Intention: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2023, 49, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Wu, Q.; Su, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, L. Coping Styles Mediated the Association Between Perceived Organizational Support and Resilience in Emergency Nurses Exposed to Workplace Violence: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2025, 27, e70018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Li, J.; Wu, F.; Peng, X.; Zhou, F. Investigation of occupational burnout status and influencing factors among emergency department healthcare workers using the MBI-GS Scale. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2024, 49, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, E.; Lupo, R.; Calabro, A.; Cornacchia, M.; Conte, L.; Marchisio, D.; Caldararo, C.; Carvello, M.; Carriero, M.C. Mapping Potential Risk Factors in Developing Burnout Syndrome between Physicians and Registered Nurses Suffering from an Aggression in Italian Emergency Departments. J. Psychopathol. 2021, 27, 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- Bordignon, M.; Marziale, M.H.P.; Sutherland, M.A.; Monteiro, I. Factors Related to Work Ability among Nursing Professionals from Urgent and Emergency Care Units: A Cross-Sectional Study. Work 2023, 74, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, J.R.; Cash, R.E.; Kurth, J.D.; Gage, C.B.; Mercer, C.B.; Panchal, A.R. National Examination of Occupational Hazards in Emergency Medical Services. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 80, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Liu, L.; Cai, J.; Yang, Y. Effect of Noise in the Emergency Department on Occupational Burnout and Resignation Intention of Medical Staff. Noise Health 2024, 26, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, G.; Chen, Z.J.; Lu, Q. Effects of Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction and Workplace Violence on Turnover Intention of Emergency Nurses: A Cross-sectional Study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 26, e12854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, G.L.; Cooper, S.S.; Bresler, S.A.; Tamsukhin, S. Emergency Department Workers’ Perceived Support and Emotional Impact After Workplace Violence. J. Forensic Nurs. 2025, 21, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, L.; Diao, D.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J. Effort-Reward Imbalance and Health Outcomes in Emergency Nurses: The Mediating Role of Work-Family Conflict and Intrinsic Effort. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1515593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, H.; Lan, L.; Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Zhong, L.; Zhu, L.; Gao, Y. Effects of Effort-Reward Imbalance on Emergency Nurses’ Health: A Mediating and Moderating Role of Emotional Exhaustion and Work-Family Conflict. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1580501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, L.T.; O’Connell, N.; Huffman, C.; McDonald, S.; Gibbs, M.; Miller, C.; Danhauer, S.C.; Reed, M.; Mason, L.; Foley, K.L.; et al. Job-Related Factors Associated with Burnout and Work Engagement in Emergency Nurses: Evidence to Inform Systems-Focused Interventions. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2025, 51, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshammari, M.; Aljarash, A.; Alharbi, J.; Alrashdi, A.; Alshammari, K.; Alshammeri, R.; Alanezi, S.; Qaladi, O.A. Quality of Work Life and Related Factors among Nurses in Emergency and Critical Care Departments in Saudi Arabia in 2023: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2025, 14, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Onrubia, I.M.; Resta Sánchez, E.J.; Cabañero Contreras, T.; Perona Moratalla, A.B.; Molina Alarcón, M. Bienestar, Burnout y Sueño Del Personal de Enfermería de Urgencias En Turnos de 12 Horas. Enfermería Clínica 2025, 35, 102141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senken, B.; Welch, J.; Sarmiento, E.; Weinstein, E.; Cushman, E.; Kelker, H. Factors Influencing Emergency Medicine Worker Shift Satisfaction: A Rapid Assessment of Wellness in the Emergency Department. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2024, 5, e13315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, K.Q.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Abdul-Manan, H.-H.; Mohd-Salleh, Z.-A.H.; Abdul-Mumin, K.H.; Rahman, H.A. Strategies Used to Cope with Stress by Emergency and Critical Care Nurses. Br. J. Nurs. 2019, 28, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuwanich, N.; Sandmark, H.; Akhavan, S. Emergency Department Nurses’ Experiences of Occupational Stress: A Qualitative Study from a Public Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand. Work 2016, 53, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westphal, M.; Bingisser, M.-B.; Feng, T.; Wall, M.; Blakley, E.; Bingisser, R.; Kleim, B. Protective Benefits of Mindfulness in Emergency Room Personnel. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 175, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, S.M.; Honn, K.A.; Gaddameedhi, S.; Van Dongen, H.P.A. Shift Work: Disrupted Circadian Rhythms and Sleep—Implications for Health and Well-Being. Curr. Sleep Med. Rep. 2017, 3, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pascual, M.; Pérez-Ferreiro, M.; Rodríguez de Castro, S.; Cerro-González, M.D.C.; Recio-Vivas, A.M. Occupational Stress in Healthcare Professionals in Spain: A Multicenter Study. Hisp. Health Care Int. 2025, 23, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, R.; Schoeman, R. Burnout in Emergency Department Staff: The Prevalence and Barriers to Intervention. S. Afr. J. Psychiatry 2023, 29, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J.; Porter, C.O.; Ng, K.Y. Justice at the Millennium: A Meta-Analytic Review of 25 Years of Organizational Justice Research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Gong, H.; Ma, D.; Wu, X. Association between Workplace Psychological Violence and Work Engagement among Emergency Nurses: The Mediating Effect of Organizational Climate. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, K. Why Working Expectations Need to Change to Protect Doctors and the Quality of Patient Care: A Perspective from Down-Under. J. Pediatr. Rehabit. Med. 2023, 16, 463–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, L.H.; Johnson, J.; Watt, I.; Tsipa, A.; O’Connor, D.B. Healthcare Staff Wellbeing, Burnout, and Patient Safety: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, A.; Panagopoulou, E.; Esmail, A.; Richards, T.; Maslach, C. Burnout in Healthcare: The Case for Organisational Change. BMJ 2019, 366, l4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudkjoebing, L.A.; Bungum, A.B.; Flachs, E.M.; Eller, N.H.; Borritz, M.; Aust, B.; Rugulies, R.; Rod, N.H.; Biering, K.; Bonde, J.P. Work-Related Exposure to Violence or Threats and Risk of Mental Disorders and Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2020, 46, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandaciva, S. How Does the NHS Compare to the Health Care Systems of Other Countries? The King’s Fund: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pourmand, A.; Caggiula, A.; Barnett, J.; Ghassemi, M.; Shesser, R. Rethinking Traditional Emergency Department Care Models in a Post-Coronavirus Disease-2019 World. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2023, 49, 520–529.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitz, D.A.; Wellenius, G.A. Can Cross-Sectional Studies Contribute to Causal Inference? It Depends. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 192, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakır, O.; Akkoç, İ.; Arun, K.; Dığrak, E.; Uluırmak Ünlüeroğlugil, H.S. The Complex Dynamics of Violence and Burnout in Healthcare: A Closer Look at Physicians and Nurses. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2025, 72, e70075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, A.; Campbell, P.; Cheyne, J.; Cowie, J.; Davis, B.; McCallum, J.; McGill, K.; Elders, A.; Hagen, S.; McClurg, D.; et al. Interventions to Support the Resilience and Mental Health of Frontline Health and Social Care Professionals during and after a Disease Outbreak, Epidemic or Pandemic: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD013779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmansyah, M.E.; Isnanto, S.H. The Influence of Job Satisfaction and Reward Systems on Turnover Intention. Dinasti Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2025, 6, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Mental Health Strategy of the National Health System 2022–2026; Government of Spain: Madrid, Spain, 2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galindo-Herrera, R.; Pabón-Carrasco, M.; Romero-Castillo, R.; Garrido-Bueno, M. Biopsychosocial and Occupational Health of Emergency Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120430

Galindo-Herrera R, Pabón-Carrasco M, Romero-Castillo R, Garrido-Bueno M. Biopsychosocial and Occupational Health of Emergency Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(12):430. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120430

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalindo-Herrera, Rafael, Manuel Pabón-Carrasco, Rocío Romero-Castillo, and Miguel Garrido-Bueno. 2025. "Biopsychosocial and Occupational Health of Emergency Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nursing Reports 15, no. 12: 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120430

APA StyleGalindo-Herrera, R., Pabón-Carrasco, M., Romero-Castillo, R., & Garrido-Bueno, M. (2025). Biopsychosocial and Occupational Health of Emergency Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nursing Reports, 15(12), 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120430