The Impact of an Onboarding Plan for Newly Hired Nurses and Nursing Assistants: Results of a Quasi-Experimental Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Study Setting and Sampling

- Inclusion criteria:

- Participants were newly hired healthcare professionals with a valid nursing or auxiliary nursing degree.

- Participants had no prior working experience within any hospital of the HM Hospitales group.

- Participants had full-time contracts.

- Exclusion criteria:

- Participants had part-time contracts.

- Participants had previously worked in the HM hospital group.

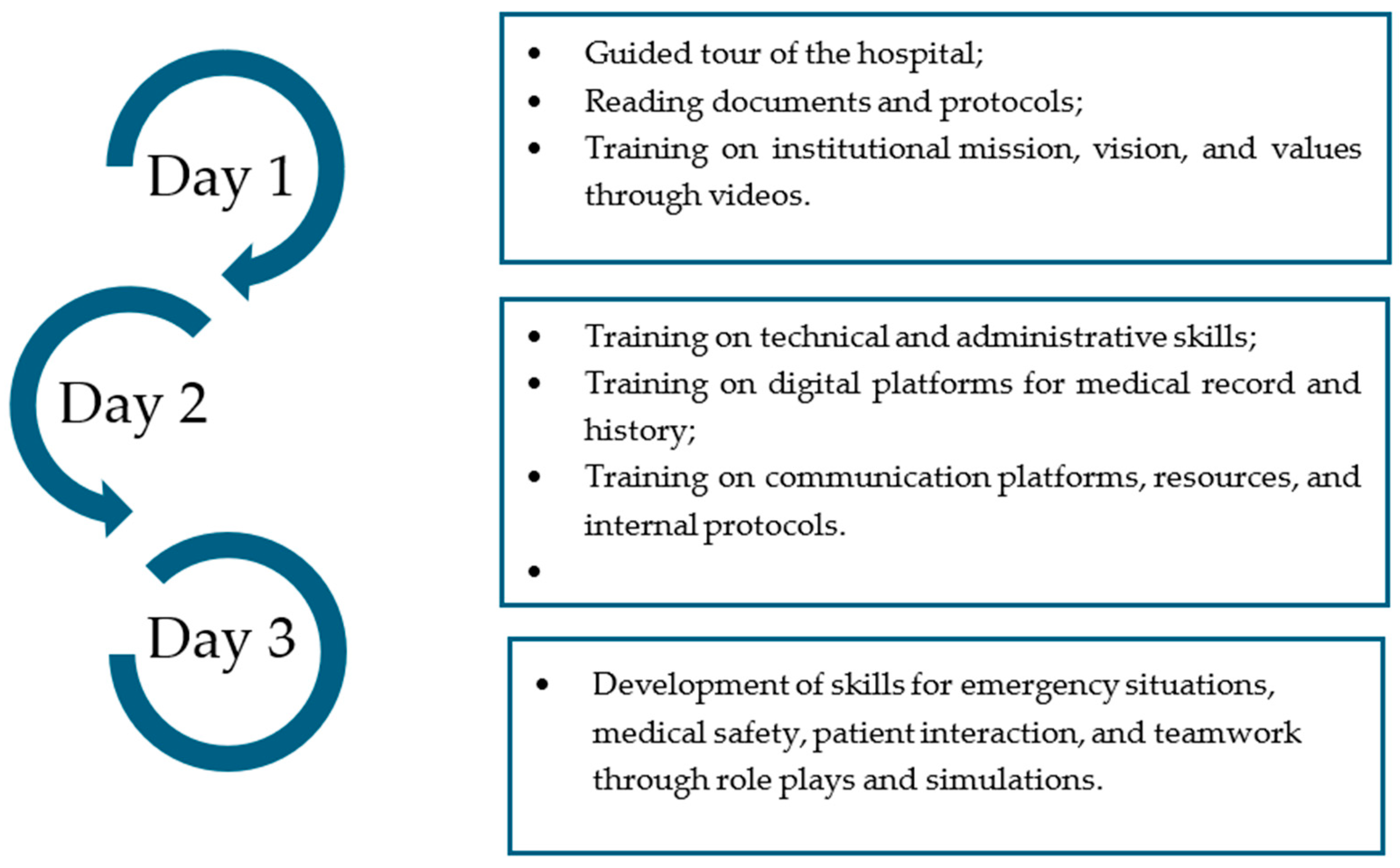

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Outcome Measures

2.5.1. Adaptation to the Work Environment

- The management of digital tools is a domain that evaluates the use of the hospital’s intranet and digital platforms to locate key documents such as nursing care protocols, occupational risk prevention documentation, and incident notification reporting through 6 questions.

- Knowledge of clinical protocols assesses the use of the institution’s digital platform for nursing care and reporting medical records through 5 questions.

- Compliance with administrative regulations focuses on the correct use of the platform for prescription, interpretation, and validation of pharmacological treatments for carrying out pharmaceutical reports through 4 questions. This domain is answered only by nurses.

- Decision-making and problem-solving is a domain that assesses knowledge of emergency protocols, emergency contact numbers, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) procedures, and evacuation plan reporting through 4 questions.

- Diet measures the ability to introduce dietary plans in the hospital system according to medical orders through 2 questions. This domain is answered only by nursing assistants.

- The domain patient safety practices assess the knowledge of patient safety, allergies, hygiene, and warning reports through 6 questions.

- Administrative skills is a domain that covers the use of expense forms and the correct entry of billing data through 2 questions.

2.5.2. Sociodemographic Data

2.5.3. Satisfaction

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IG | Intervention Group |

| CG | Control Group |

| IQR | Interquartile Rank |

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation |

References

- Goens, B.; Giannotti, N. Transformational leadership and nursing retention: An integrative review. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2024, 2024, 3179141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.; Ojemeni, M.M.; Kalamani, R.; Tong, J.; Crecelius, M.L. Relationship between nurse burnout, patient and organisational outcomes: Systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 119, 103933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Z.; Yang, P.; Singer, S.J.; Pfeffer, J.; Mathur, M.B.; Shanafelt, T. Nurse burnout and patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2443059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, N.; Lavreysen, O.; Boone, A.; Bouman, J.; Szemik, S.; Baranski, K.; Godderis, L.; De Winter, P. Retaining healthcare workers: A systematic review of strategies for sustaining power in the workplace. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buljac-Samardzic, M.; Doekhie, K.D.; van Wijngaarden, J.D.H. Interventions to improve team effectiveness within health care: A systematic review of the past decade. Hum. Resour. Health. 2020, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berggren, A.; Sandoz, A.; Carrillo, A.; Heusinkvelt, S. Standardized onboarding increases intention to stay with the organization. J. Nurse Pract. 2024, 20, 105011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharum, H.; Ismail, A.; McKenna, L.; Mohamed, Z.; Ibrahim, R.; Hassan, N.H. Success factors in adaptation of newly graduated nurses: A scoping review. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, H.; Kester, K.; Cadavero, A.; O’Brien, S. Implementation of an evidence-based onboarding program to optimize efficiency and care delivery in an intensive care unit. J. Nurses Prof. Dev. 2023, 39, E190–E195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, H.M.; Scott, M.; Gorham, R.; Hunt, E. Impact of nurse residency programs on retention and job satisfaction: An integrative review. Eur. Sci. J. 2024, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurguri, A. Structured training of new nurses employees: The basis for a successful induction process. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2024, 9, 2399–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, M.H.; Alenezi, A. Nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction: The role of technology integration, self-efficacy, social support, and prior experience. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Miller, C.A.; Jones, C.; Blakeney, T. Organizational socialization: Optimizing experienced nurses’ onboarding. Nurs. Manag. 2023, 54, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás Lizcano, A.; Caravaca Alcaraz, B.; Rodríguez Molina, F.J.; Arias Estero, J.; Candel Rubio, C.; Rodríguez Molina, A.; Sánchez Fernández, A.M.; Estrada Bernal, D.; Salmerón Aroca, J.A. Programa de acogida al personal de enfermería de nueva incorporación y alumnos en prácticas en la Fundación Hospital Cieza. Enferm Glob. 2004, 3, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena. Plan de Acogida Profesional; Servicio Andaluz de Salud: Sevilla, Spain, 2022; Available online: https://www.hospitalmacarena.es/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2022-PLAN-ACOGIDA-PROFESIONAL-HUVM-GENERAL.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Ortega-Arias, M. Plan de Acogida al Personal de Nueva Incorporación en el Hospital de Jaén. Líderes Cuidados 2024, 20, e14904. Available online: https://ciberindex.com/index.php/lc/article/view/e14904 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Ruiz-Romero, A.; García-Costa, L.; Durban-Carrillo, G.; Bosch-Alcaraz, A. Eficacia de un plan de acogida teórico-práctico dirigido a profesionales de enfermería de nueva incorporación en una Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos Pediátrica: Estudio piloto. Enferm. Intensiva 2022, 33, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, K.; Fink, R.R.; Krugman, A.M.; Propst, F.J. The graduate nurse experience. J. Nurs. Adm. 2004, 34, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Patrician, P.A. Measuring organizational traits of hospitals: The Revised Nursing Work Index. Nurs. Res. 2000, 49, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taormina, R.J. The organizational socialization inventory. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 1994, 2, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertiwi, R.I.; Hariyati, T.S. Effective orientation programs for new graduate nurses: A systematic review. Enferm. Clin. 2019, 29, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernawaty, E.; Hariati, S.; Saleh, A. Program components, impact, and duration of implementing a new nurse orientation program in hospital contexts: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2024, 7, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitoun, R.A.; Said, N.B.; de Tantillo, L. Clinical nurse competence and its effect on patient safety culture: A systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, L.; Shkrabak, S. Seamless transition: Strategies for effective new nurse orientation and practice integration. Nurse Lead. 2025, 23, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elendu, C.; Amaechi, D.C.; Okatta, A.U.; Amaechi, E.C.; Elendu, T.C.; Ezeh, C.P.; Elendu, I.D. The impact of simulation-based training in medical education: A review. Medicine 2024, 103, e38813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raqueno, L.; Rückholdt, M.; Ndwiga, D.W.; Gupta, M.; Raeburn, T. Peer support strategies for newly qualified nurses: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2025, 170, 105145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Patel, J.; Patel, V.; Pandya, H.; Shah, K. Effectiveness of induction training on newly joined employee knowledge and hospital performance. Glob. J. Qual. Saf. Healthc. 2023, 6, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalithabai, D.S.; Ammar, W.M.; Alghamdi, K.S.; Aboshaiqah, A.E. Using action research to evaluate a nursing orientation program in a multicultural acute healthcare setting. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2021, 8, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swensen, S.J.; Shanafelt, T. An organizational framework to reduce professional burnout and bring back joy in practice. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2017, 43, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, K.L.; Janke, R.; Duchscher, J.E.; Phillips, R.; Kaur, S. Best practices of formal new graduate transition programs: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 94, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, E.G.; Sembar, M.C.; Sadler, F. Onboarding new graduate nurses using assessment-driven personalized learning to improve knowledge, critical thinking, and nurse satisfaction. J. Nurses Prof. Dev. 2021, 39, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Des Jarlais, D.C.; Lyles, C.; Crepaz, N.; Trend Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: The TREND statement. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Global (n = 128) | Control (n = 64) | Intervention (n = 64) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median, IQR) | 25.00 [23.00;28.00] | 25.00 [24.00;27.00] | 24.00 [23.00;28.25] | 0.061 | |

| Sex (n, %) | Women | 127 (99.22%) | 64 (100.00%) | 63 (98.44%) | 1.000 |

| Nationality (n, %) | Chile | 15 (11.72%) | 6 (9.38%) | 9 (14.06%) | 0.530 |

| Colombia | 4 (3.12%) | 2 (3.12%) | 2 (3.12%) | ||

| Spain | 101 (78.91%) | 52 (81.25%) | 49 (76.56%) | ||

| Peru | 4 (3.12%) | 3 (4.69%) | 1 (1.56%) | ||

| Romania | 2 (1.56%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (3.12%) | ||

| Ukraine | 1 (0.78%) | 1 (1.56%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| Venezuela | 1 (0.78%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (1.56%) | ||

| Previous Experience (months; median, IQR) | 12.00 [5.75;24.00] | 12.50 [9.75;18.00] | 9.00 [2.00;25.25] | 0.196 | |

| Global (n = 72) | Control (n = 36) | Intervention (n = 36) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median, IQR) | 23.00 [19.75;25.00] | 20.00 [18.00;21.00] | 25.00 [24.00;26.00] | <0.001 | |

| Sex (n, %) | Women | 61 (84.72%) | 31 (86.11%) | 30 (83.33%) | 1.000 |

| Nationality (n, %) | Chile | 6 (8.33%) | 4 (11.11%) | 2 (5.56%) | 0.018 |

| Colombia | 4 (5.56%) | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (11.11%) | ||

| Spain | 57 (79.17%) | 31 (86.11%) | 26 (72.22%) | ||

| Romania | 1 (1.39%) | 1 (2.78%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| Venezuela | 4 (5.56%) | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (11.11%) | ||

| Previous Experience (months; median, IQR) | 6.00 [0.75;12.00] | 1.50 [0.00;9.00] | 6.00 [6.00;15.00] | 0.001 | |

| Domains of the GAML Tool | Total (n = 128) | Control (n = 64) | Intervention (n = 64) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global (median, IQR) | 19.00 [12.75;25.00] | 12.50 [10.00;15.00] | 25.00 [22.00;27.00] | <0.001 |

| Management of digital tools (median, IQR) | 3.00 [1.00;5.00] | 1.00 [0.00;3.00] | 5.00 [4.00;6.00] | <0.001 |

| Informed consent (n, %) | 77 (60.16%) | 17 (26.56%) | 60 (93.75%) | <0.001 |

| Nursing care (n, %) | 77 (60.16%) | 21 (32.81%) | 56 (87.50%) | <0.001 |

| Procedures (n, %) | 77 (60.16%) | 21 (32.81%) | 56 (87.50%) | <0.001 |

| Protocols (n, %) | 55 (42.97%) | 7 (10.94%) | 48 (75.00%) | <0.001 |

| Occupational risk prevention (n, %) | 38 (29.69%) | 0 (0.00%) | 38 (59.38%) | <0.001 |

| Incidents (n, %) | 70 (54.69%) | 19 (29.69%) | 51 (79.69%) | <0.001 |

| Knowledge of clinical protocols (median, IQR) | 5.00 [4.00;5.00] | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 5.00 [5.00;5.00] | <0.001 |

| Vital sign register (n, %) | 104 (81.25%) | 40 (62.50%) | 64 (100.00%) | <0.001 |

| Pain register (n, %) | 105 (82.03%) | 41 (64.06%) | 64 (100.00%) | <0.001 |

| Evolutive register (n, %) | 123 (96.09%) | 59 (92.19%) | 64 (100.00%) | 0.058 |

| Lab test (n, %) | 111 (86.72%) | 47 (73.44%) | 64 (100.00%) | <0.001 |

| Radiology test management (n, %) | 103 (80.47%) | 47 (73.44%) | 56 (87.50%) | 0.074 |

| Adherence to administrative regulations (median, IQR) | 4.00 [4.00;4.00] | 3.00 [3.00;4.00] | 4.00 [4.00;4.00] | 0.001 |

| Medication guidelines (n, %) | 118 (92.19%) | 55 (85.94%) | 63 (98.44%) | 0.021 |

| Pharmacy incidence (allergies) (n, %) | 117 (91.41%) | 54 (84.38%) | 63 (98.44%) | 0.012 |

| Treatment interpretation (n, %) | 122 (95.31%) | 58 (90.62%) | 64 (100.00%) | 0.028 |

| Treatment validation (n, %) | 125 (97.66%) | 61 (95.31%) | 64 (100.00%) | 0.244 |

| Problem-solving and decision-making (median, IQR) | 1.00 [0.00;4.00] | 0.00 [0.00;1.00] | 4.00 [3.00;4.00] | <0.001 |

| CPR protocol (n, %) | 76 (59.38%) | 22 (34.38%) | 54 (84.38%) | <0.001 |

| CPR circuit (n, %) | 60 (46.88%) | 4 (6.25%) | 56 (87.50%) | <0.001 |

| Emergency advice (n, %) | 64 (50.00%) | 8 (12.50%) | 56 (87.50%) | <0.001 |

| Evacuation protocol (n, %) | 35 (27.34%) | 0 (0.00%) | 35 (54.69%) | <0.001 |

| Patient safety (median, IQR) | 5.00 [4.00;6.00] | 4.00 [2.00;4.00] | 6.00 [5.00;6.00] | <0.001 |

| Platform skills (n, %) | 52 (40.62%) | 3 (4.69%) | 49 (76.56%) | <0.001 |

| 10 rights (n, %) | 107 (83.59%) | 45 (70.31%) | 62 (96.88%) | <0.001 |

| Allergies identification (n, %) | 95 (74.22%) | 31 (48.44%) | 64 (100.00%) | <0.001 |

| Hand hygiene (n, %) | 116 (90.62%) | 54 (84.38%) | 62 (96.88%) | 0.034 |

| Advice (n, %) | 99 (77.34%) | 35 (54.69%) | 64 (100.00%) | <0.001 |

| Patient identification (n, %) | 85 (66.41%) | 22 (34.38%) | 63 (98.44%) | <0.001 |

| Billing (median, IQR) | 1.00 [0.00;2.00] | 0.00 [0.00;0.00] | 2.00 [1.00;2.00] | <0.001 |

| Expense report (n, %) | 63 (49.22%) | 9 (14.06%) | 54 (84.38%) | <0.001 |

| Billing control (n, %) | 53 (41.41%) | 5 (7.81%) | 48 (75.00%) | <0.001 |

| Domains of the GAML Tool | Total (n = 72) | Control (n = 36) | Intervention (n = 36) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global (median, IQR) | 19.00 [15.00;22.00] | 15.50 [12.00;17.25] | 22.00 [20.00;23.25] | <0.001 |

| Management of digital tools (median, IQR) | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 3.00 [1.00;4.00] | 5.00 [5.00;6.00] | <0.001 |

| Informed consent (n, %) | 51 (70.83%) | 17 (47.22%) | 34 (94.44%) | <0.001 |

| Nursing care (n, %) | 45 (62.50%) | 15 (41.67%) | 30 (83.33%) | <0.001 |

| Procedures (n, %) | 53 (73.61%) | 19 (52.78%) | 34 (94.44%) | <0.001 |

| Protocols (n, %) | 45 (62.50%) | 14 (38.89%) | 31 (86.11%) | <0.001 |

| Occupational risk prevention (n, %) | 26 (36.11%) | 8 (22.22%) | 18 (50.00%) | 0.027 |

| Incidents (n, %) | 55 (76.39%) | 22 (61.11%) | 33 (91.67%) | 0.006 |

| Knowledge of clinical protocols (median, IQR) | 4.00 [3.75;5.00] | 4.00 [2.00;4.00] | 5.00 [4.00;5.00] | <0.001 |

| Vital sign register (n, %) | 55 (76.39%) | 19 (52.78%) | 36 (100.00%) | <0.001 |

| Pain register (n, %) | 59 (81.94%) | 24 (66.67%) | 35 (97.22%) | 0.002 |

| Evolutive register (n, %) | 39 (54.17%) | 14 (38.89%) | 25 (69.44%) | 0.018 |

| Lab test (n, %) | 60 (83.33%) | 25 (69.44%) | 35 (97.22%) | 0.004 |

| Radiology test management (n, %) | 57 (79.17%) | 21 (58.33%) | 36 (100.00%) | <0.001 |

| Problem-solving and decision-making (median, IQR) | 2.00 [1.00;3.00] | 1.00 [0.00;2.00] | 3.00 [2.00;3.00] | <0.001 |

| CPR protocol (n, %) | 50 (69.44%) | 16 (44.44%) | 34 (94.44%) | <0.001 |

| CPR circuit (n, %) | 2 (2.78%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (5.56%) | 0.493 |

| Emergency advice (n, %) | 53 (73.61%) | 19 (52.78%) | 34 (94.44%) | <0.001 |

| Evacuation protocol (n, %) | 28 (38.89%) | 6 (16.67%) | 22 (61.11%) | <0.001 |

| Diet (median, IQR) | 2.00 [2.00;2.00] | 2.00 [2.00;2.00] | 2.00 [2.00;2.00] | 0.160 |

| Allergy’s introduction (n, %) | 70 (97.22%) | 34 (94.44%) | 36 (100.00%) | 0.493 |

| program management (n, %) | 70 (97.22%) | 34 (94.44%) | 36 (100.00%) | 0.493 |

| Patient safety (median, IQR) | 5.00 [4.00;6.00] | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 6.00 [5.00;6.00] | <0.001 |

| Platform skills (n, %) | 33 (45.83%) | 7 (19.44%) | 26 (72.22%) | <0.001 |

| 10 rights (n, %) | 46 (63.89%) | 13 (36.11%) | 33 (91.67%) | <0.001 |

| Allergies identification (n, %) | 65 (90.28%) | 30 (83.33%) | 35 (97.22%) | 0.107 |

| Hand hygiene (n, %) | 68 (94.44%) | 32 (88.89%) | 36 (100.00%) | 0.115 |

| Advice (n, %) | 60 (83.33%) | 26 (72.22%) | 34 (94.44%) | 0.027 |

| Patient identification (n, %) | 65 (90.28%) | 30 (83.33%) | 35 (97.22%) | 0.107 |

| Billing (median, IQR) | 2.00 [1.00;2.00] | 2.00 [2.00;2.00] | 2.00 [1.00;2.00] | 0.093 |

| Expense report (n, %) | 71 (98.61%) | 35 (97.22%) | 36 (100.00%) | 1 |

| Billing control (n, %) | 58 (80.56%) | 32 (88.89%) | 26 (72.22%) | 0.137 |

| Satisfaction Variables | Total (n = 92) | Control (n = 44) | Intervention (n = 48) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information quality | ||||

| General information received about the hospital (median, IQR) | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | 4.00 [3.00;4.00] | 5.00 [4.00;5.00] | <0.001 |

| Information about the structure of the hospital (median, IQR) | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 3.00 [3.00;4.00] | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | <0.001 |

| Information about the work (median, IQR) | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | 0.087 |

| Service-specific information (median, IQR) | 4.00 [3.00;4.00] | 3.00 [3.00;4.00] | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | <0.001 |

| Amount information | ||||

| Information about digital platform (median, IQR) | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | 0.057 |

| Information about the structure of the hospital (median, IQR) | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 3.00 [3.00;4.00] | 4.00 [3.75;5.00] | 0.012 |

| Information about the pharmacy service (median, IQR) | 3.00 [2.00;4.00] | 2.00 [1.00;2.00] | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | <0.001 |

| Information about occupational risk prevention (median, IQR) | 2.00 [0.00;4.00] | 0.00 [0.00;0.00] | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | <0.001 |

| Information about work unit (median, IQR) | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 3.00 [3.00;4.00] | 5.00 [4.00;5.00] | <0.001 |

| Total satisfaction (median, IQR) | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 3.00 [3.00;4.00] | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 0.015 |

| Satisfaction Variables | Total (n = 45) | Control (n = 31) | Intervention (n = 14) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information quality | ||||

| General information received about the hospital (median, IQR) | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 4.50 [4.00;5.00] | 0.134 |

| Information about the structure of the hospital (median, IQR) | 4.00 [3.00;4.00] | 4.00 [3.00;4.00] | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | 0.029 |

| Information about the work (median, IQR) | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | 5.00 [4.00;5.00] | 0.337 |

| Service-specific information (median, IQR) | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 4.00 [3.00;4.00] | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | 0.139 |

| Amount information | ||||

| Information about digital platform (median, IQR) | 5.00 [4.00;5.00] | 5.00 [4.00;5.00] | 5.00 [4.00;5.00] | 0.826 |

| Information about the structure of the hospital (median, IQR) | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | 0.170 |

| Information about the pharmacy service (median, IQR) | 2.00 [2.00;3.00] | 2.00 [1.00;2.00] | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | <0.001 |

| Information about occupational risk prevention (median, IQR) | 0.00 [0.00;3.00] | 0.00 [0.00;0.00] | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | <0.001 |

| Information about work unit (median, IQR) | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 3.00 [3.00;4.00] | 5.00 [4.00;5.00] | 0.018 |

| Total satisfaction (median, IQR) | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 5.00 [3.50;5.00] | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 0.552 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muñoz, P.M.; Cardinal-Fernández, P.; Morales Rodríguez, Á.; Ruiz-Zaldibar, C.; de la Cuerda López, A. The Impact of an Onboarding Plan for Newly Hired Nurses and Nursing Assistants: Results of a Quasi-Experimental Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110398

Muñoz PM, Cardinal-Fernández P, Morales Rodríguez Á, Ruiz-Zaldibar C, de la Cuerda López A. The Impact of an Onboarding Plan for Newly Hired Nurses and Nursing Assistants: Results of a Quasi-Experimental Study. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(11):398. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110398

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuñoz, Pilar Montes, Pablo Cardinal-Fernández, Ángel Morales Rodríguez, Cayetana Ruiz-Zaldibar, and Alicia de la Cuerda López. 2025. "The Impact of an Onboarding Plan for Newly Hired Nurses and Nursing Assistants: Results of a Quasi-Experimental Study" Nursing Reports 15, no. 11: 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110398

APA StyleMuñoz, P. M., Cardinal-Fernández, P., Morales Rodríguez, Á., Ruiz-Zaldibar, C., & de la Cuerda López, A. (2025). The Impact of an Onboarding Plan for Newly Hired Nurses and Nursing Assistants: Results of a Quasi-Experimental Study. Nursing Reports, 15(11), 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110398