Panorama of Two Decades of Maternal Deaths in Brazil: Retrospective Ecological Time Series

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Population and Period

2.3. Data Sources and Variables

2.4. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

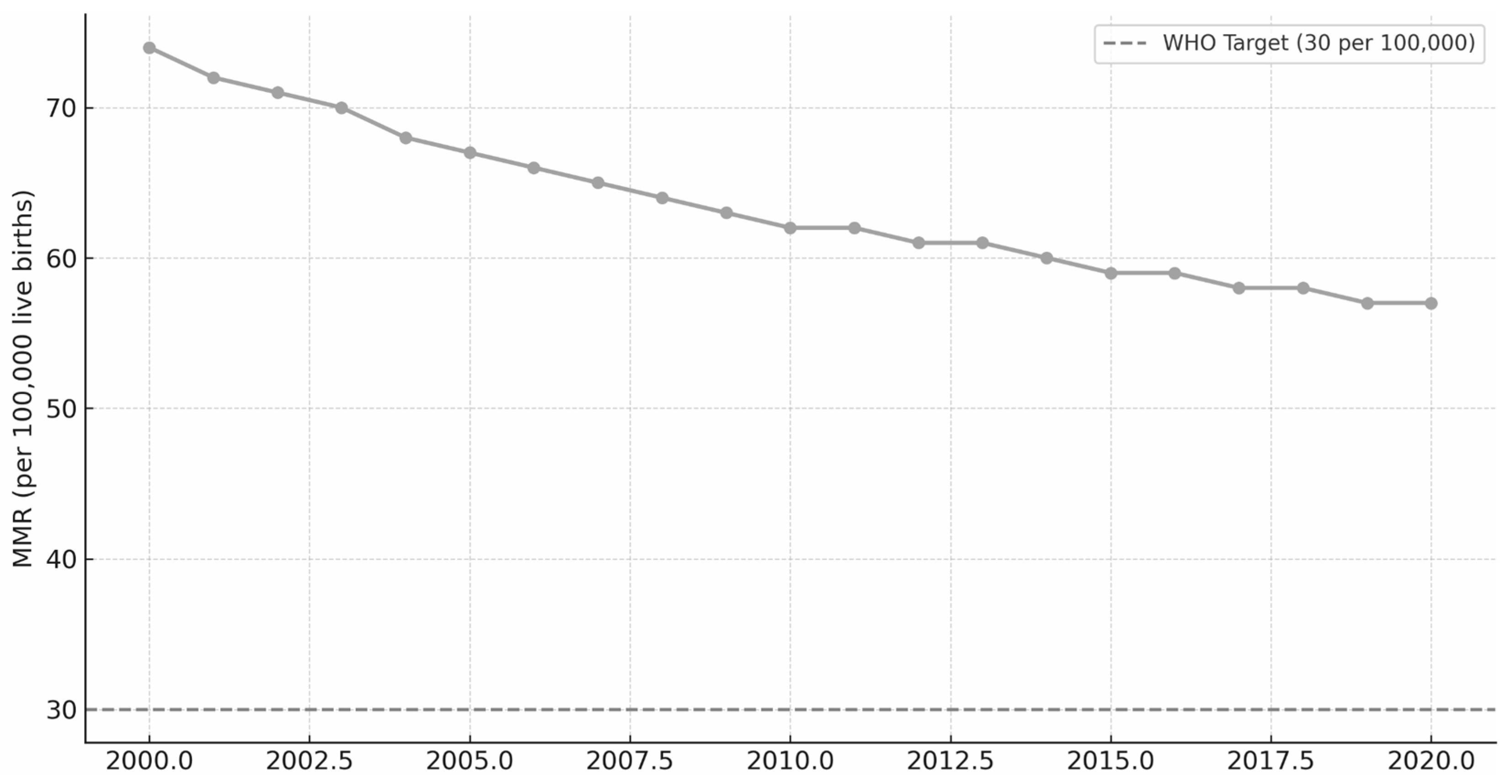

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Regional Inequalities

4.2. Risk Factors and Obstetric Causes

4.3. Health System Factors

4.4. Nursing Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICD-10 | Classification of Diseases—10th Revision |

| CSV | Comma Separated Values |

| FAPESPA | Fundação Amazônia de Amparo a Estudos e Pesquisas |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| LGBTQIA+ | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Intersex, Asexual |

| MMR | Maternal mortality ratio |

| PNSI-LGBT | Política Nacional de Saúde Integral de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis e Transexuais |

| SIM | Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade |

| SINASC | Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos |

| SUS | Sistema Único de Saúde |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. Manual dos Comitês de Mortalidade Materna, 3rd ed.; Brasília, Brazil, 2009; 104p. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/manual_comites_mortalidade_materna.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Say, L.; Souza, J.P.; Pattinson, R.C.; WHO Working Group on Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Classifications. Maternal near miss—Towards a standard tool for monitoring quality of maternal health care. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2009, 23, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, M.d.C.; Esteves-Pereira, A.P.; Bittencourt, S.A.; Domingues, R.M.S.M.; Theme Filha, M.M.; Leite, T.H.; Barbara Vasques da Silva Ayres, B.V.S.; Baldisserotto, M.L.; Nakamura-Pereira, M.; Lopes Moreira, M.E.L.; et al. Protocolo do Nascer no Brasil II: Pesquisa Nacional sobre Aborto, Parto e Nascimento. Cad Saúde Pública 2024, 40, e00036223. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/csp/a/cPg3d9dRfqS3RHhqZrjmRVg/?format=pdf&lang=pt (accessed on 2 October 2025). [PubMed]

- Leal, M.d.C.; Szwarcwald, C.L.; Almeida, P.V.B.; Aquino, E.M.L.; Barreto, M.L.; Barros, F.; Victora, C. Saúde reprodutiva, materna, neonatal e infantil nos 30 anos do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS). Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2018, 23, 1915–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, I.V.G.; Maranhão, T.A.; Frota, M.M.C.; da Araujo, T.K.A.; de Torres, S.d.R.F.; Rocha, M.I.F.; da Silva Xavier, M.E.; Sousa, G.J.B. Mortalidade materna no Brasil: Análise de tendências temporais e agrupamentos espaciais. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2024, 29, e05012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonove, K.C.A.; Lansky, S.; Soares, V.M.N.; Matozinhos, F.P.; Martins, E.F.; Silva, R.A.R.; de Souza, K.V. Time series analysis: Trend in late maternal mortality in Brazil, 2010-2019. Cad. Saúde Pública 2024, 40, e00168223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Gama, S.G.N.; Bittencourt, S.A.; Theme Filha, M.M.; Takemoto, M.L.S.; Lansky, S.; de Frias, P.G.; da Silva Ayres, B.V.; Domingues, R.M.S.M.; Dias, M.A.B.; Esteves-Pereira, A.P.; et al. Mortalidade materna: Protocolo de um estudo integrado à pesquisa Nascer no Brasil II. Cad. Saude Publica 2024, 40, e00107723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintori, J.A.; Mendes, L.M.C.; Monteiro, J.C.d.S.; Gomes-Sponholz, F. Epidemiologia da morte materna e o desafio da qualificação da assistência. Acta Paul Enferm. 2022, 35, eAPE00251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruas, C.A.M.; Quadros, J.F.C.; Rocha, J.F.D.; Rocha, F.C.; Andrade Neto, G.R.; de Piris, Á.P.; Meira Rios, B.R.; Silva Pereira, S.G.; Alves Leão Ribeiro, C.F.; Mendes Silva Leão, G.M. Profile and spatial distribution on maternal mortality. Rev. Bras. Saude Mater. Infant. 2020, 20, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, M.d.C.; Gama, S.G.N.d.; Pereira, A.P.E.; Pacheco, V.E.; Carmo, C.N.d.; Santos, R.V. A cor da dor: Iniquidades raciais na atenção pré-natal e ao parto no Brasil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2017, 33, e00078816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fapespa. Fundação Amazônia de Amparo a Estudos e Pesquisas. Taxa de Mortalidade Materna (2019–2023). Belém: Fapespa. 2024. Available online: https://fapespa.pa.gov.br/sistemas/anuario2024/tabelas/social/5.5-saude/tab-5.5.3-taxa-de-mortalidade-materna-2019-a-2023.htm (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Ferreira, M.E.S.; Coutinho, R.Z.; Queiroz, B.L. Morbimortalidade materna no Brasil e a urgência de um sistema nacional de vigilância do near miss materno. Cad. Saude Publica 2023, 39, e00013923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa-Assis, A.I.; Santana, V.S. Occupation and maternal mortality in Brazil. Rev. Saude Publica 2020, 54, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M.; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 805–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, B.G.; Sousa, G.M.L.; Queres, R.L.; Lourenço, L.P.; Martins, L.P.O.M.; Fonseca, S.C.; Boschi-Pinto, C.; Kawa, H. Tendência da Razão de Mortalidade Materna Segundo Raça/cor no Estado do Rio de Janeiro, 2008 a 2021. Cien Saude Coletiva. Available online: http://cienciaesaudecoletiva.com.br/artigos/tendencia-da-razao-de-mortalidade-materna-segundo-racacor-no-estado-do-rio-de-janeiro-2008-a-2021/19606 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Silva, A.D.; Guida, J.P.S.; Santos, D.d.S.; Santiago, S.M.; Surita, F.G. Racial disparities and maternal mortality in Brazil: Findings from a national database. Rev. Saúde Pública 2024, 58, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, J.P.; Day, L.T.; Rezende-Gomes, A.C.; Zhang, J.; Mori, R.; Baguiya, A.; Jayaratne, K.; Osoti, A.; Vogel, J.P.; Campbell, O.; et al. A global analysis of the determinants of maternal health and transitions in maternal mortality. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e306–e316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, A.L.J.; Miranda, W.D.; Silveira, F.; Paes-Sousa, R. A Agenda 2030 e os Objetivos de Desenvolvimento Sustentável (ODS) como estratégia para equidade em saúde e territórios sustentáveis e saudáveis. Saúde Debate 2024, 48, e8828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, F.; Fu, Q.; Cheng, P.; Zuo, J.; Wu, Y. Time trends in maternal hypertensive disorder incidence in Brazil, Russian Federation, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS): An age-period-cohort analysis for the GBD 2021. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorcély, D.F.; Surita, F.G.; Costa, M.L.; de Siqueira Guida, J.P. Maternal deaths due to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Brazil from 2012 until 2023: A cross-sectional populational-based study. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2025, 44, 2492094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.B.R.A.d.A.; Angulo-Tuesta, A.; Massari, M.T.R.; Augusto, L.C.R.; Gonçalves, L.L.M.; Silva, C.K.R.T.d.; Minoia, N.P. Avaliação da Rede Cegonha: Devolutiva dos resultados para as maternidades no Brasil. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2021, 26, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarqi, M.N. The Impact of Prenatal Care on the Prevention of Neonatal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Global Health Interventions. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Júnior, A.J.; Zanetti, A.C.B.; Dias, B.M.; Bernandes, A.; Gastaldi, F.M.; Gabriel, C.S. Occurrence and preventability of adverse events in hospitals: A retrospective study. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2023, 76, e20220025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.; Chong, M.Y.C.; Link, H.M.; Pejchinovska, M.; Gazeley, U.; Ahmed, S.M.A.; Chou, D.; Moller, A.-B.; Simpson, D.; Alkema, L.; et al. Global and regional causes of maternal deaths 2009–2020: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e626–e634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.d.P.d.; Kale, P.L.; Fonseca, S.C.; Nantes, T.; Alt, N.N. Factors associated with severe maternal, fetuses and neonates’ outcomes in a university hospital in Rio de Janeiro State. Rev. Bras. Saude Mater. Infant. 2023, 23, e20220135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, E.; Gong, J.; Daskalopoulou, Z.; Quigley, M.A.; Alderdice, F.; Harrison, S.; Fellmeth, G. Global contribution of suicide to maternal mortality: A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e087669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batulan, Z.; Bhimla, A.; Higginbotham, E.J. (Eds.) Advancing Research on Chronic Conditions in Women; 6, Chronic Conditions That Predominantly Impact or Affect Women Differently; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK607719/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Oliveira, G.; Jesus, R.; Dias, P.; Alvares, L.; Nepomuceno, A.; Sakai, L.; Daher, M.C.; Silva, O.N.; Pinto, E.M.H. Epidemiological profile of Covid-19 cases and deaths in a reference hospital in the state of Goiás, Brazil. J. Trop. Pathol. 2023, 52, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.P. Mortalidade materna no Brasil: A necessidade de fortalecer os sistemas de saúde. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2011, 33, 273–279. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbgo/a/KhkMpnx8gMWbYFpQqbZBYJL/?format=html&lang=pt (accessed on 4 October 2025). [PubMed]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Gestão Estratégica e Participativa. Departamento de Apoio à Gestão Participativa. Política Nacional de Saúde Integral de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis e Transexuais / Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Gestão Estratégica e Participativa, Departamento de Apoio à Gestão Participativa. Brasília: 1. ed., 1. reimp. Ministério da Saúde. 2013. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/politica_nacional_saude_lesbicas_gays.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Cardoso, J.C.; Santos, S.D.; Santos, J.G.S.; Pereira, D.M.R.; Almeida, L.C.G.; Souza, Z.C.S.N.; Oliveira, J.F.; de Sousa, A.R.; de Santana Carvalho, E.S. Stigma in doctors’ and nurses’ perception regarding prenatal care for transgender men. Acta Paul Enferm. 2024, 37, eAPE00573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menandro, L.M.T.; Oliveira, E.F.A.; Esquenazi Borrego, A.; Garcia, M.L.T. Maternal Mortality in Brazil. In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Social Problems; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas Junior, A.B.; Bezerra, A.B.; da Nobrega, A.A.; Rabello, D.L.; Lobo, A.P.; Maciel, E.L.; de Oliveira, L.C. Distância entre a residência e o local dos óbitos maternos: Desigualdades regionais, étnico-raciais e territoriais no Brasil, 2018 a 2023. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2025, 49, e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenorio, D.S.; de Matos Brasil, A.G.; Nogueira, B.G.; Rolim Lima, N.N.; Araújo, J.E.B.; Rolim Neto, M.L. High maternal mortality rates in Brazil: Inequalities and the struggle for justice. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2022, 14, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folha de São Paulo. Increase in Maternal Deaths Is Marked by Racial and Regional Inequalities. Science & Health. 15 March 2023. Available online: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/internacional/en/scienceandhealth/2023/03/increase-in-maternal-deaths-is-marked-by-racial-and-regional-inequalities.shtml (accessed on 20 August 2025).

| Category | Maternal Deaths (n=) | Maternal Deaths (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Region | ||

| Northern Region | 5147 | 12.6% |

| Northeast Region | 13,748 | 33.6% |

| Southeast Region | 14,129 | 34.5% |

| Southern Region | 4555 | 11.1% |

| Central-West Region | 3328 | 8.1% |

| Age | ||

| 10 to 14 years old | 346 | 0.8% |

| 15 to 19 years old | 5105 | 12.4% |

| 20 to 29 years old | 16,381 | 40% |

| 30 to 39 years old | 15,548 | 38% |

| 40 to 49 years old | 3418 | 8.3% |

| 50 to 59 years old | 85 | 0.2% |

| 70 to 79 years old | 1 | 0% |

| Age ignored | 23 | 0.1% |

| Race | ||

| White | 13,648 | 33.3% |

| Black | 4446 | 10.8% |

| Yellow | 123 | 0.3% |

| Brown | 19,773 | 48.3% |

| Indigenous | 566 | 1.3% |

| Ignored | 2351 | 5.7% |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 20,579 | 50.3% |

| Married | 12,338 | 30.1% |

| Widower | 307 | 0.7% |

| Legally separated | 696 | 1.7% |

| Other | 3819 | 9.3% |

| Ignored | 3168 | 7.7% |

| Education | ||

| None | 1532 | 3.7% |

| 1 to 3 years | 4660 | 11.3% |

| 4 to 7 years | 9538 | 23.3% |

| 8 to 11 years | 12,151 | 29.7% |

| 9 to 11 years | 3 | 0.1% |

| 12 years and over | 3725 | 9.1% |

| Ignored | 9298 | 23.7% |

| Total | 40,907 | 100% |

| Category | Maternal Deaths (n=) | Maternal Deaths (%) | IC 95% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chapter ICD-10 | |||

| I. Infectious diseases | 844 | 0.41% | 0.38–0.44 |

| II. Neoplasms | 10 | 0.4% | 0.002–0.008 |

| IV. Endocrine/metabolic | 1 | 0.5% | - |

| V. Mental disorders | 36 | 0.1% | 0.012–0.023 |

| XV. Pregnancy/childbirth/puerperium | 40,016 | 19.5% | 19.393–19.737 |

| Type of cause | |||

| Direct obstetric | 26,957 | 13.1% | 13.033–13.327 |

| Indirect obstetric | 12,665 | 6.1% | 6.088–6.297 |

| Obstetric unspecified | 1281 | 0.6% | 0.592–0.661 |

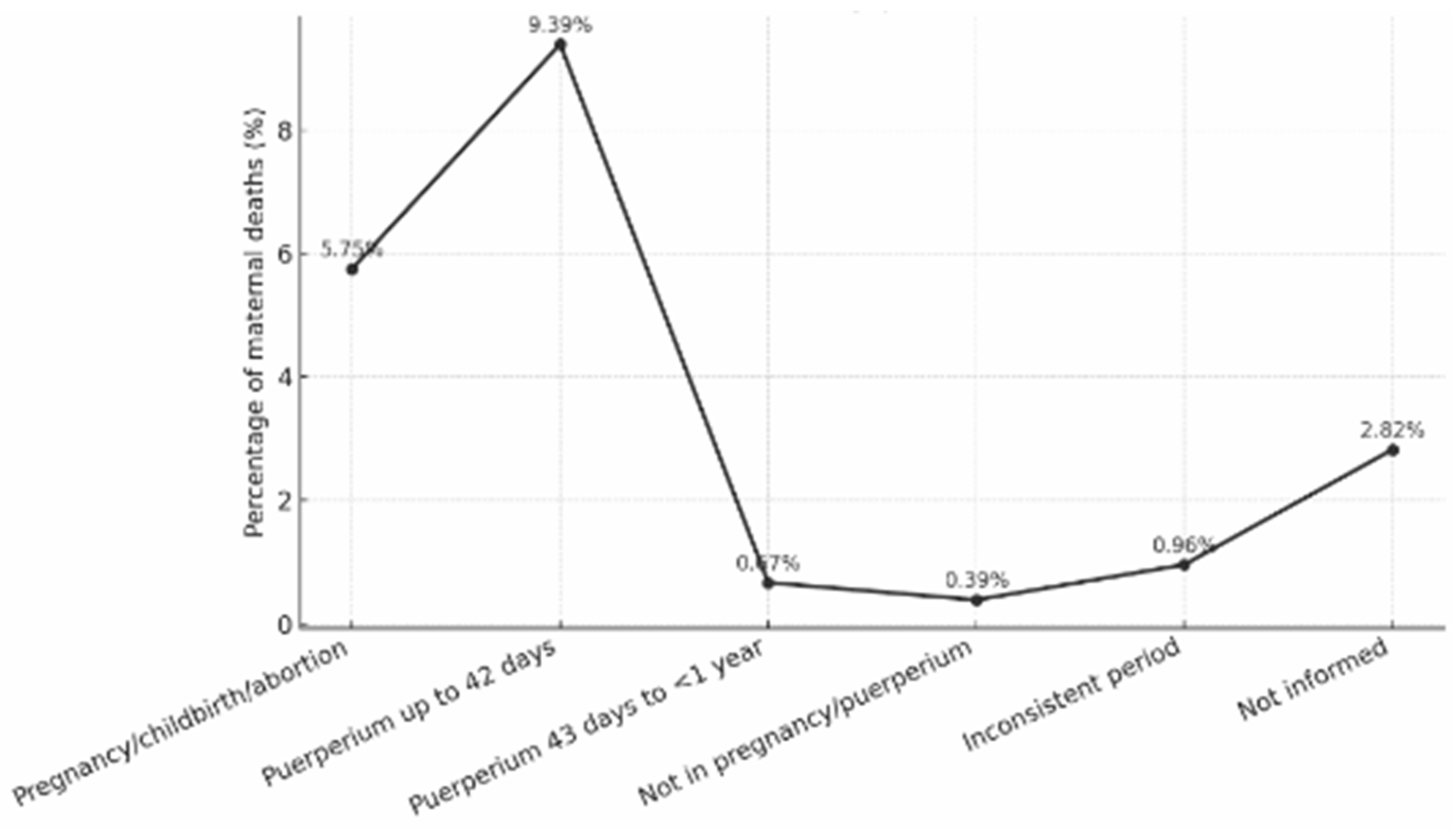

| Períod of death | |||

| Pregnancy/childbirth/abortion | 11,763 | 5.7% | 5.650–5.852 |

| Puerperium up to 42 days | 19,206 | 9.3% | 9.264–9.517 |

| Puerperium 43 days to <1 year | 1382 | 0.6% | 0.640–0.711 |

| Not in pregnancy or puerperium | 803 | 0.3% | 0.366–0.420 |

| Inconsistent period | 1976 | 0.9% | 0.924–1.009 |

| Not informed | 5777 | 2.8% | 2.753–2.896 |

| Place of occurrence | |||

| Hospital | 37,288 | 18.2% | 18.064–18.398 |

| Other establishments | 882 | 0.4% | 0.403–0.460 |

| Domicile | 1513 | 0.7% | 0.703–0.777 |

| Public road | 525 | 0.2% | 0.235–0.279 |

| Others | 648 | 0.3% | 0.292–0.341 |

| Ignored | 51 | 0.2% | 0.018–0.032 |

| Death investigated | |||

| Investigated with record | 23,123 | 11.3% | 11.168–11.443 |

| Investigated without a record | 3548 | 1.7% | 1.678–1.791 |

| Not investigated | 4482 | 2.1% | 2.128–2.255 |

| Not applicable | 9754 | 4.7% | 4.677–4.861 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

dos Santos, G.G.; Vidotti, G.A.G.; Ichikawa, C.R.d.F.; Lima, C.F.; Dionizio, L.d.A.; Maia, J.S.; Zihlmann, K.F.; Neto, J.G.d.O.; Nascimento, W.S.M.; Cardoso, A.M.R.; et al. Panorama of Two Decades of Maternal Deaths in Brazil: Retrospective Ecological Time Series. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110396

dos Santos GG, Vidotti GAG, Ichikawa CRdF, Lima CF, Dionizio LdA, Maia JS, Zihlmann KF, Neto JGdO, Nascimento WSM, Cardoso AMR, et al. Panorama of Two Decades of Maternal Deaths in Brazil: Retrospective Ecological Time Series. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(11):396. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110396

Chicago/Turabian Styledos Santos, Gustavo Gonçalves, Giovana Aparecida Gonçalves Vidotti, Carolliny Rossi de Faria Ichikawa, Cindy Ferreira Lima, Leticia de Almeida Dionizio, Janize Silva Maia, Karina Franco Zihlmann, Joaquim Guerra de Oliveira Neto, Wágnar Silva Morais Nascimento, Alexandrina Maria Ramos Cardoso, and et al. 2025. "Panorama of Two Decades of Maternal Deaths in Brazil: Retrospective Ecological Time Series" Nursing Reports 15, no. 11: 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110396

APA Styledos Santos, G. G., Vidotti, G. A. G., Ichikawa, C. R. d. F., Lima, C. F., Dionizio, L. d. A., Maia, J. S., Zihlmann, K. F., Neto, J. G. d. O., Nascimento, W. S. M., Cardoso, A. M. R., Carvalho, J. M. d. N., Santa Rosa, P. L. F., Mouta, R. J. O., Reis, C. H. R., Aguiar, C. d. A., Santos, D. d. S., Silva, B. P. d., Silva, A. L. C. d., Nascimento, E. S. d., ... Pedraza, L. L. (2025). Panorama of Two Decades of Maternal Deaths in Brazil: Retrospective Ecological Time Series. Nursing Reports, 15(11), 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110396