First Experiences with Last Aid Courses as Tool for Public Palliative Care Education in Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants, Data Collection and Analysis

- Inclusion criteria: all questionnaires from Last Aid Course participants from 18 years of age, who provided informed consent and completed all the answers to the questionnaires properly.

- Exclusion criteria: participants who did not respond to the questionnaire.

- Pre-analysis, with floating reading and the establishment of information about the topic, through exhaustiveness, representativeness, homogeneity, and relevance to the research objectives

- Exhaustive exploration of the material for coding, creation of context units, and categorization

- Interpretation of the data and necessary inferences.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Data

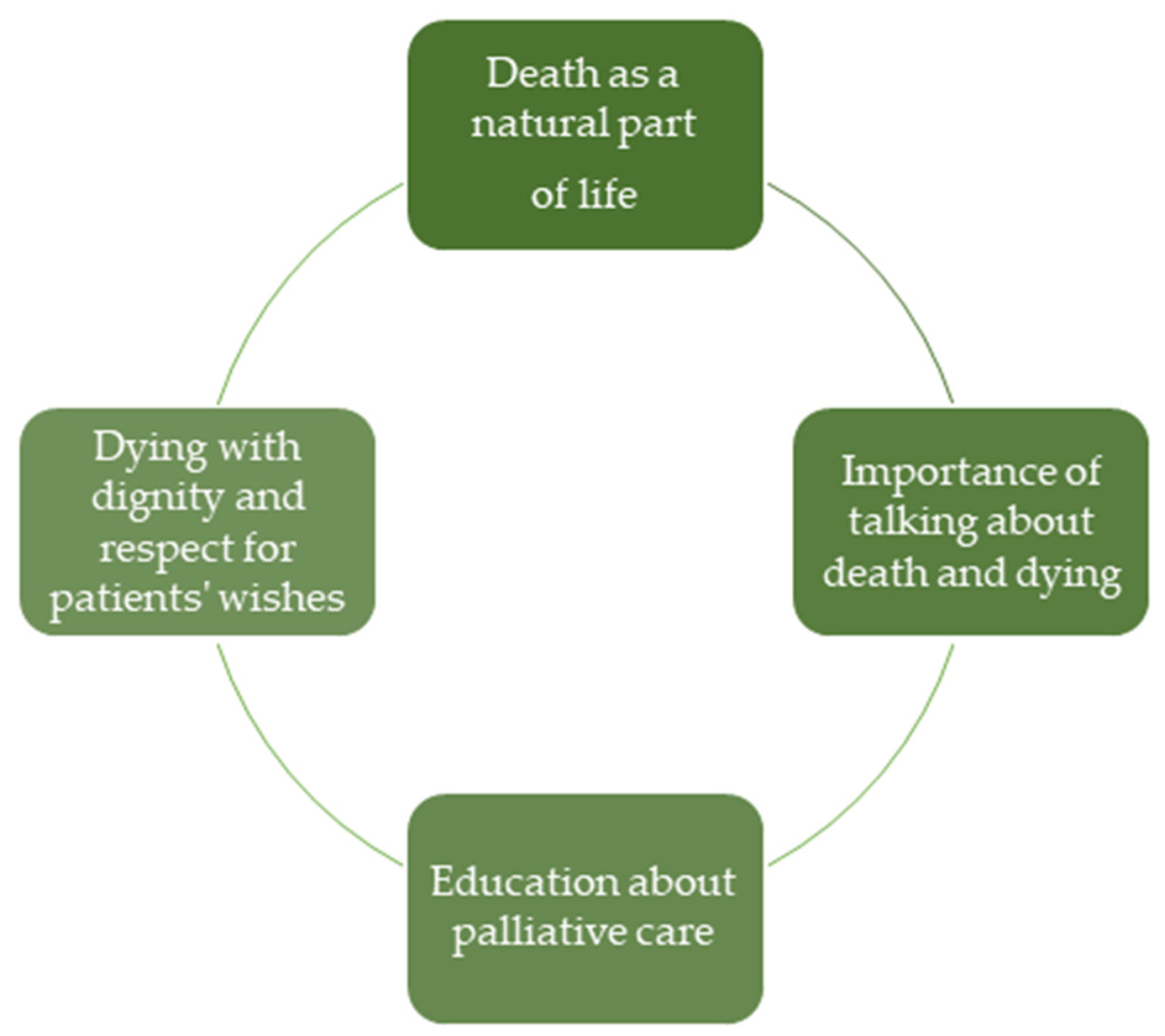

3.2. Qualitative Data

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PPCE | public palliative care education |

| CHW | Community Health Worker |

| PCU | Primary Care Unit |

Appendix A

- 1.

- Why did you take part in the LAST AID course? (please tick as many as apply)

- 2.

- How did you find out about the LAST AID course? (Please tick as appropriate)

- 3.

- Evaluation of the Course Content

| Very Poor | Poor | Neither poor nor good | Good | Very Good | I don’t like to answer | |

| Dying as a normal part of life | ||||||

| Planning ahead | ||||||

| Relieving suffering | ||||||

| Final goodbyes | ||||||

| the whole LAST AID course |

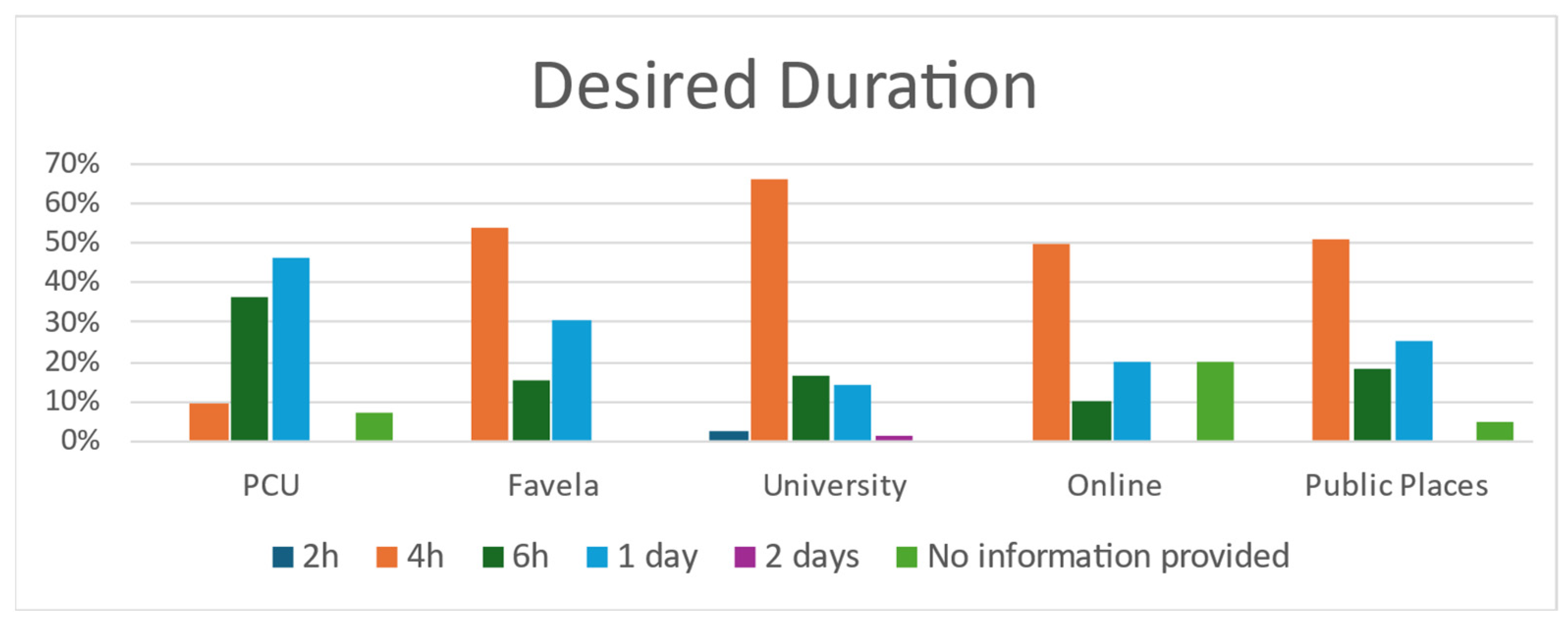

- 4.

- Currently the course lasts 3.5 h. How long would you suggest the duration of the Last Aid course should be?

- 5.

- Your personal experience of LAST AID course

| Yes | No | Don’t know | I don’t like to answer | |

| I have understood what was been taught to me. | ||||

| I have learned new things. | ||||

| I now feel more confident to talk about death and dying. | ||||

| I now feel more confident to support people living with terminal illness | ||||

| I now feel more confident to provide end-of-life care. | ||||

| I now feel more confident to support those experiencing bereavement | ||||

| I will recommend the course to others. |

- 6.

- Which of the topics would you like more information on in the Last Aid course? (You could choose more than one topic)

- 7.

- Evaluation of LAST AID course delivery

| Very Poor | Poor | Neither poor nor good | Good | Very Good | I don’t like to answer | |

| Organization of the course | ||||||

| Structure of the course | ||||||

| Time for group discussions | ||||||

| Opportunity for personal involvement in group discussions | ||||||

| Facilitation of the course | ||||||

| Group dynamics (Involvement of other participants) | ||||||

| Time-management during the course | ||||||

| Virtual Environment |

- 8.

- What is the most important take home message for you from the LAST AID course?

- 9.

- What gender do you identify as?

- 10.

- How old are you? ________

- 11.

- What is your education level?

- 12.

- What is your profession? ______________

- 13.

- Do you have any other comments or suggestions?

Appendix B

References

- Finkelstein, E.A.; Bhadelia, A.; Goh, C.; Baid, D.; Singh, R.; Bhatnagar, S.; Connor, S.R. Cross Country Comparison of Expert Assessments of the Quality of Death and Dying 2021. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022, 63, e419–e429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.F.; Silva, J.F.M.D.; Cabrera, M. Cuidados paliativos: Percurso na atenção básica no Brasil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2022, 38, e00130222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, J.M.G.; Baid, D.; Johnson, F.R.; Finkelstein, E.A. What is a Good Death? A Choice Experiment on Care Indicators for Patients at End of Life. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022, 63, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgstrom, E. What is a good death? A critical discourse policy analysis. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024, 14, e2546–e2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2015 Quality of Death Index. Available online: https://impact.economist.com/health/2015-quality-death-index (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria GM/MS nº 3.681, de 7 de Maio de 2024. In Diário Oficial da União; Imprensa Nacional: Brasília, Brazil, 2024. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/web/dou/-/portaria-gm/ms-n-3.681-de-7-de-maio-de-2024-*-565726225 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Ghisleni, R.C.; Saavedra, L.P.; Valandro, C.G. Avaliação do conhecimento em cuidados paliativos entre médicos de família e comunidade. Rev. Bras. Med. Fam. Comunidade 2023, 18, 3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.F.; de Oliveira, N.M.S. Programa educacional em cuidados paliativos para os profissionais de saúde: Uma revisão sistemática. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, e18011628885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamarchi, G.C.G.; Leitão, B.F.B. Estratégias educativas em cuidados paliativos para profissionais da saúde. Rev. Bioética 2023, 31, e3491PT. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, M.G.D.R.; Silva, A.E.; Coelho, L.P.; Martins, M.R.; de Souza, M.T.; Trotte, L.A.C. Slum compassionate community: Expanding access to palliative care in Brazil. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2023, 57, e20220432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollig, G.; Brandt, F.; Ciurlionis, M.; Knopf, B. Last Aid Course. An Education For All Citizens and an Ingredient of Compassionate Communities. Healthcare 2019, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.; Rosenberg, J.P.; Bollig, G.; Haberecht, J. Last Aid and Public Health Palliative Care: Towards the development of personal skills and strengthened community action. Prog. Palliat. Care 2020, 28, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollig, G.; Neylon, S.; Niedermann, E.; Zelko, E. The Last Aid Course as Measure for Public Palliative Care Education: Lessons Learned from the Implementation Process in Four Different Countries. In Palliative Care—Current Practice and Future Perspectives; Bollig, G., Zelko, E., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollig, G.; Heller, A. The last aid course—A Simple and Effective Concept to Teach the Public about Palliative Care and to Enhance the Public Discussion about Death and Dying. Austin Palliat. Care 2016, 1, 1010. [Google Scholar]

- Bollig, G. Palliative Care für Alte und Demente Menschen Lernen und Lehren; Lit Verlag: Wien, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, K. Implantação dos Cursos de Últimos Socorros no Brasil (CDUS)—Relato de Experiência. In Proceedings of the X Congresso Brasileiro de Cuidados Paliativos, Fortaleza, Brazil, 13–16 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bollig, G.; Meyer, S.; Knopf, B.; Schmidt, M.; Bauer, E.H. First Experiences with Online Last Aid Courses for Public Palliative Care Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 9, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollig, G.; Gräf, K.; Gruna, H.; Drexler, D.; Pothmann, R. “We Want to Talk about Death, Dying and Grief and to Learn about End-of-Life Care”—Lessons Learned from a Multi-Center Mixed-Methods Study on Last Aid Courses for Kids and Teens. Children 2024, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollig, G.; Bauer, E.H. Last Aid Courses as measure for public palliative care education for adults and children—A narrative review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 8242–8253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirro, U.B.d.P.; Castilho, R.; Crispim, D.; de Lucena, C. . Atlas Dos Cuidados Paliativos No Brasil; Academia Nacional de Cuidados Paliativos: São Paulo, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, S.R.; Sepulveda Bermedo, M.C.; World Health Organization; International Observatory for End of Life Care. Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life; Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Neergaard, M.A.; Olesen, F.; Andersen, R.S.; Sondergaard, J. Qualitative description—The poor cousin of health research? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2009, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo; Edições 70: São Paulo, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bollig, G.; Brandt Kristensen, F.; Wolff, D.L. Citizens appreciate talking about death and learning end-of-life care—A mixed-methods study on views and experiences of 5469 Last Aid Course participants. Prog. Palliat. Care 2021, 29, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaden, L.; Broadfoot, K.; Carolan, C.; Muirhead, K.; Neylon, S.; Keen, J. Last Aid Training Online: Participants’ and Facilitators’ Perceptions from a Mixed-Methods Study in Rural Scotland. Healthcare 2022, 10, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.F.D.; Almeida, M.T.P.D.; Ferreira, M.G.; Pinto, I.C.; Amaral, G.G. Importância do agente comunitário de saúde nas ações da Estratégia Saúde da Família: Revisão integrativa: REVISÃO INTEGRATIVA. Rev. Baiana Saúde Pública 2022, 46, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, E.; Bollig, G.; Becker, G.; Boehlke, C. Lessons Learned from Introducing Last Aid Courses at a University Hospital in Germany. Healthcare 2021, 9, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollig, G.; Schmidt, M.; Aumann, D.; Knopf, B. Der Letzte Hilfe Kurs professionell—Erste Erfahrungen mit einem eintägigen niedrigschwelligen Palliative Care Fortbildungsangebot für Personal aus dem Gesundheitswesen. Z. Für Palliativmedizin 2023, 24, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.S.M.; Cassavia, M.F.d.C.; Salman, B.C.S.; Salman, A.A.; Bryan, L.; de Oliveira, L.C. Política Nacional de Cuidados Paliativos: Desafios da Qualificação Profissional em Cuidados Paliativos no Brasil. Rev. Bras. Cancerol. 2024, 70, e-044753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellehear, A. Compassionate communities: End-of-life care as everyone’s responsibility. QJM Int. J. Med. 2013, 106, 1071–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.E.; Prates, C.M.; Couto, L.d.S.; Oliveira, L.C. Comunidade Compassiva das Favelas da Rocinha e Vidigal: Estratégia para Auxílio no Controle do Câncer. Rev. Bras. Cancerol. 2024, 70, e-104714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profissionais da Saúde e Moradores Levam Cuidados Paliativos a Doentes em Favelas. Folha de S.Paulo. Available online: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/equilibrioesaude/2023/08/profissionais-da-saude-e-moradores-levam-cuidados-paliativos-a-doentes-em-favelas.shtml (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- De Souza Minayo, M.C.; Constantino, P.; Do Nascimento Mangas, R.M.; Pereira, T.F.D.S. Experiências de agentes comunitários de saúde com pessoas idosas dependentes e vulneráveis. Rev. Pesq. Qual. 2024, 12, 570–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coube, M.; Nikoloski, Z.; Mrejen, M.; Mossialos, E. Inequalities in unmet need for health care services and medications in Brazil: A decomposition analysis. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2023, 19, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Educação. PARECER CNE/CES Nº: 265/2022, de 03 de Novembro de 2023. In Diário Oficial da União; Imprensa Nacional: Brasília, Brazil, 2023. Available online: https://portal.mec.gov.br/docman/marco-2022-pdf/238001-pces265-22/file (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Castro, A.A.; Taquette, S.R.; Marques, N.I. Cuidados paliativos: Inserção do ensino nas escolas médicas do Brasil. Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. 2021, 45, e056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.A. Compartilhando Experiências do Ensino em Cuidados Paliativos na Medicina; Academia Nacional de Cuidados Paliativos: São Paulo, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Setting | nº of Courses | Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Favela | 4 (12.5%) | 32 (9.3%) |

| University | 9 (28.1%) | 105 (30.6%) |

| PCU 1 | 2 (6.25%) | 42 (12.2%) |

| Public Place | 10 (31.25%) | 121 (35.3%) |

| Online | 7 (21.9%) | 43 (12.5%) |

| Total | 32 | 343 |

| Women | Men | No Information Provided | Participants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Favela | 12 (92.3%) | 1 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 |

| University | 69 (80.2%) | 17 (19.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 86 |

| PCU | 41 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 41 |

| Public Place | 67 (77.9%) | 17 (19.8%) | 2 (2.3%) | 86 |

| Online | 16 (80.0%) | 4 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 20 |

| Total | 205 (83.3%) | 39 (15.9%) | 2 (0.8%) | 246 |

| Yes | No | No Information Provided | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I will recommend the course to others | 242 (98.4%) | 4 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| I learned new things | 243 (98.8%) | 2 (0.8%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Setting | Very Poor (n, %) | Poor (n, %) | Neither Poor Nor Good (n, %) | Good (n, %) | Very Good (n, %) | No Information Provided (n, %) | Total Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCU 1 | 1 (2.4%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | 38 (92.7%) | 1 (2.4%) | 41 |

| Favela | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 (100%) | 0 | 13 |

| University | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (4.7%) | 81 (94.2%) | 1 (1.2%) | 86 |

| Online | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (15.0%) | 17 (85.0%) | 0 | 20 |

| Public Places | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (12.8%) | 72 (83.7%) | 3 (3.5%) | 86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schmid, K.; Cury, P.M.; Schmidt, M.; Bollig, G.; Nascimento, J.S. First Experiences with Last Aid Courses as Tool for Public Palliative Care Education in Brazil. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110386

Schmid K, Cury PM, Schmidt M, Bollig G, Nascimento JS. First Experiences with Last Aid Courses as Tool for Public Palliative Care Education in Brazil. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(11):386. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110386

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchmid, Karin, Patricia Maluf Cury, Marina Schmidt, Georg Bollig, and Janaina Santos Nascimento. 2025. "First Experiences with Last Aid Courses as Tool for Public Palliative Care Education in Brazil" Nursing Reports 15, no. 11: 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110386

APA StyleSchmid, K., Cury, P. M., Schmidt, M., Bollig, G., & Nascimento, J. S. (2025). First Experiences with Last Aid Courses as Tool for Public Palliative Care Education in Brazil. Nursing Reports, 15(11), 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110386