Development and Content Validation of a Person-Centered Care Instrument for Healthcare Providers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.2. Existing PCC Scales

1.3. Conceptual Framework Development

1.3.1. Concept 1: Respect and Empathy

1.3.2. Concept 2: Partnership and Trust

1.3.3. Concept 3: Individualization and Consideration for Diversity

1.3.4. Concept 4: Shared Decision-Making

1.3.5. Concept 5: Emotional and Psychological Support

1.3.6. Concept 6: Comprehensive Care and Holistic Perspective

1.3.7. Concept 7: Effective Information Sharing with Care Recipients

1.3.8. Concept 8: Flexible Care

1.4. Research Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

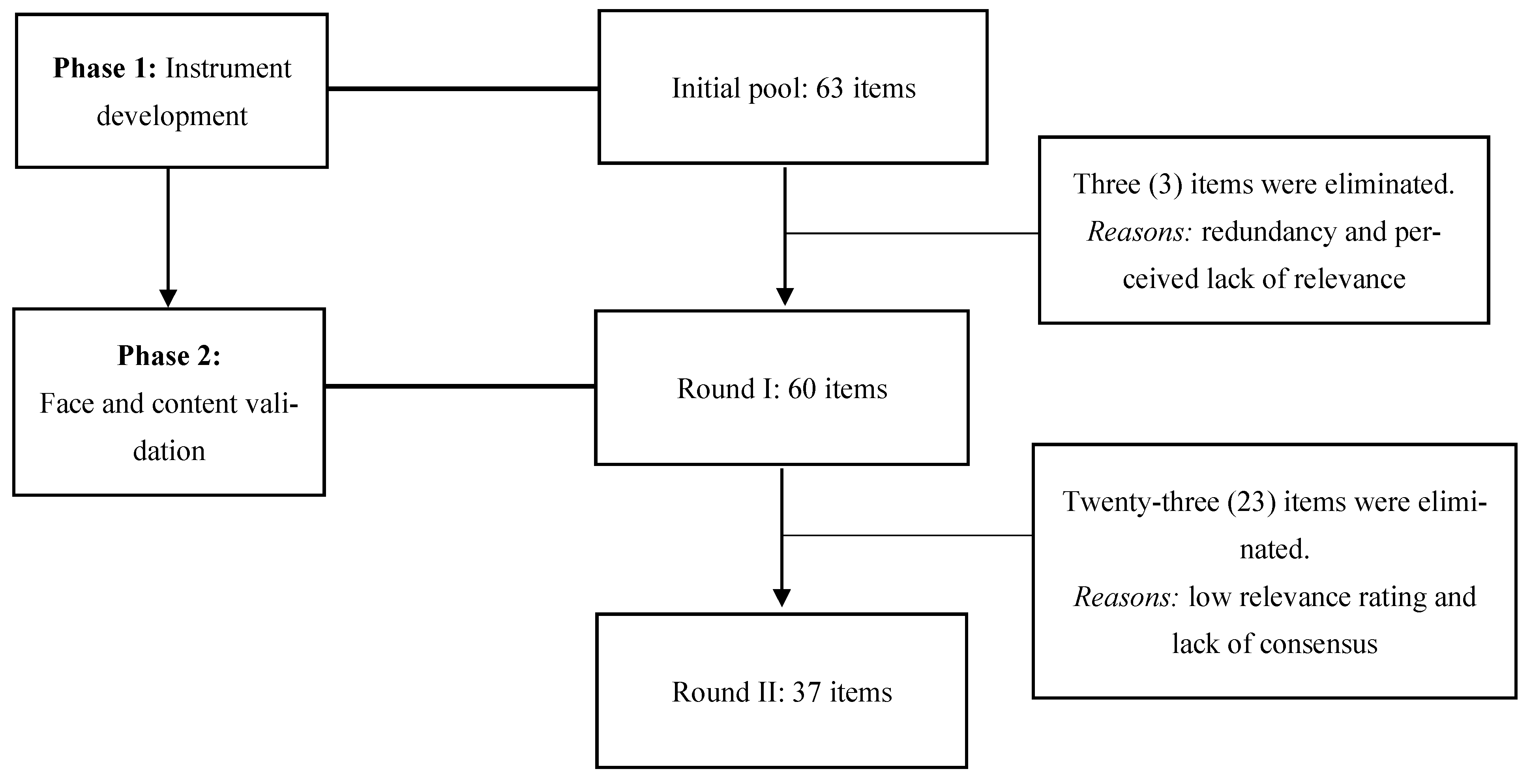

2.1. Study Design and Phases

2.1.1. Phase 1: Instrument Development

2.1.2. Phase 2: Face and Content Validation

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Expert Panel

3.2. Instrument Refinement and Content Validity

3.2.1. Round 1 Results

3.2.2. Round 2 Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Content Validity

4.2. Comparison of Existing PCC Scale and Developed PCCI

4.3. Interpretation of the PCCI Used in Practice

4.3.1. Practical and Clinical Significance of the PCCI

4.3.2. Implications for Practice and Education: Insights Based on Each PCCI Concept

Concept 1: Respect and Empathy

Concept 2: Partnership and Trust

Concept 3: Individualization and Consideration for Diversity

Concept 5: Emotional and Psychological Support

Concept 6: Comprehensive Care and Holistic Perspective

Concept 7: Effective Information Sharing with Care Recipients

Concept 8: Flexible Care

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCC | Person-centered care |

| PCCI | Person-centered care instrument |

| I-CVI | Item-level content validity index |

| UA | Universal agreement |

References

- Katz, N.T.; Jones, J.; Mansfield, L.; Gold, M. The impact of health professionals’ language on patient experience: A case study. J. Patient Exp. 2022, 9, 23743735221092572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundtable on Quality Care for People with Serious Illness; Board on Health Care Services; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating the Patient and Caregiver Voice into Serious Illness Care: Proceedings of a Workshop; Graig, L., Alper, J., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; p. 24802. ISBN 978-0-309-46028-6. [Google Scholar]

- Valestrand, E.A.; Kvernenes, M.; Kinsella, E.A.; Hunskaar, S.; Schei, E. Transforming Self-experienced vulnerability into professional strength: A dialogical narrative analysis of medical students’ reflective writing. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2024, 29, 1593–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, L.; Feng, M.; You, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guan, C.; Liu, Y. Experiences of older people, healthcare providers and caregivers on implementing person-centered care for community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulter, A.; Oldham, J. Person-centred care: What is it and how do we get there? Future Hosp. J. 2016, 3, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, M.; Fiorillo, A.; Brandi, C.; Di Vincenzo, M.; Egerhazi, A.; Hiltensperger, R.; Kawohl, W.; Kovacs, A.I.; Rossler, W.; Slade, M.; et al. Impact of clinical decision-making participation and satisfaction on outcomes in mental health practice: Results from the CEDAR European longitudinal study. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2022, 34, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malenfant, S.; Jaggi, P.; Hayden, K.A.; Sinclair, S. Compassion in healthcare: An updated scoping review of the literature. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, V.; Choy-Brown, M.; Williams, N.; Marcus, S.C. Implementing person-centered care planning: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021, 72, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Gao, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Hao, Y. Differentiation between two healthcare concepts: Person-centered and patient-centered care. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2016, 3, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Jang, M.H.; Sun, M.J. Factors influencing person-centered care among psychiatric nurses in hospitals. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balqis-Ali, N.Z.; Saw, P.S.; Anis-Syakira, J.; Weng, H.F.; Sararaks, S.; Lee, S.W.H.; Abdullah, M. Healthcare provider person-centred practice: Relationships between prerequisites, care environment and care processes using structural equation modelling. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vareta, D.A.; Oliveira, C.; Família, C.; Ventura, F. Perspectives on the Person-Centered Practice of Healthcare Professionals at an Inpatient Hospital Department: A Descriptive Study. IJERPH 2023, 20, 5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montori, V.M.; Ruissen, M.M.; Hargraves, I.G.; Brito, J.P.; Kunneman, M. Shared Decision-Making as a Method of Care. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2023, 28, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edvardsson, D.; Fetherstonhaugh, D.; Nay, R.; Gibson, S. Development and initial testing of the person-centered care assessment tool (P-CAT). Int. Psychogeriatr. 2010, 22, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.Y.; Roberts, T.; Grau, B.; Edvardsson, D. Person-centered climate questionnaire-patient in english: A psychometric evaluation study in long-term care settings. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 61, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhonen, R.; Välimäki, M.; Leino-Kilpi, H. “Individualised care” from patients’, nurses’ and relatives’ perspective—A review of the literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2002, 39, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, P.; McCance, T.; McCormack, B. The development and testing of the person-centred practice inventory—Staff (PCPI-S). Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2017, 29, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, B.; McCance, T.V. Development of a framework for person-centered nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; Fitzpatrick, A.; Azim, F.T.; Ariza-Vega, P.; Bellwood, P.; Burns, J.; Burton, E.; Fleig, L.; Clemson, L.; Hoppmann, C.A.; et al. Defining and implementing patient-centered care: An umbrella review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, C.F.; Bergland, A.; Debesay, J.; Bye, A.; Langaas, A.G. Striking a balance: Health care providers’ experiences with home-based, patient-centered care for older people—A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1991–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.J.; Manalili, K.; Jolley, R.J.; Zelinsky, S.; Quan, H.; Lu, M. How to practice person-centred care: A conceptual framework. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormack, B.; McCance, T. Person-Centred Practice in Nursing and Health Care: Theory and Practice, 2nd ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-118-99056-8. [Google Scholar]

- McCance, T.; Slater, P.; McCormack, B. Using the caring dimensions inventory as an indicator of person-centred nursing. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education. 2015. Available online: https://nexusipe.org/informing/resource-center/picker-institute%E2%80%99s-eight-principles-person-centered-care (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Alkhaibari, R.A.; Smith-Merry, J.; Forsyth, R.; Raymundo, G.M. Patient-centered care in the Middle East and North African region: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesus, T.S.; Papadimitriou, C.; Bright, F.A.; Kayes, N.M.; Pinho, C.S.; Cott, C.A. Person-centered rehabilitation model: Framing the concept and practice of person-centered adult physical rehabilitation based on a scoping review and thematic analysis of the literature. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, D.; Choi, J. Person-centered rehabilitation care and outcomes: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 93, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person-Centered Care. Person-centered care: A definition and essential elements. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, L.; Jakobsson Ung, E.; Swedberg, K.; Ekman, I. Efficacy of Person-centred care as an intervention in controlled trials—A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramm, J.M.; Nieboer, A.P. Validation of an instrument to assess the delivery of patient-centred care to people with intellectual disabilities as perceived by professionals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amati, F.; McDonald, A.M.; Majeed, A.; Dubois, E.; Rawaf, S. Implementation and evaluation of patient centred care in experimental studies from 2000–2010: Systematic review. Int. J. Pers. Centred Med. 2011, 1, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, K.R.; Shattell, M.; Johnson, M.E. Capturing the Interpersonal Process of Psychiatric Nurses: A model for engagement. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, S.S.; Kendall, E.; Sav, A.; King, M.A.; Whitty, J.A.; Kelly, F.; Wheeler, A.J. Patient-centered approaches to health care: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2013, 70, 567–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, R.M.; Street, R.L. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2011, 9, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hower, K.I.; Vennedey, V.; Hillen, H.A.; Kuntz, L.; Stock, S.; Pfaff, H.; Ansmann, L. Implementation of patient-centred care: Which organisational determinants matter from decision maker’s perspective? Results from a qualitative interview study across various health and social care organisations. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2008.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Framework on Integrated, People-Centred Health Services. 2016. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_39-en.pdf?ua=1%26ua=1 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Niederberger, M.; Schifano, J.; Deckert, S.; Hirt, J.; Homberg, A.; Köberich, S.; Kuhn, R.; Rommel, A.; Sonnberger, M. The DEWISS network Delphi studies in social and health sciences—Recommendations for an interdisciplinary standardized reporting (DELPHISTAR). Results of a Delphi study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranger, J.; Homberg, A.; Sonnberger, M.; Niederberger, M. Reporting Guidelines for Delphi techniques in health sciences: A methodological review. Z. Für Evidenz Fortbild. Und Qual. Im Gesundheitswesen 2022, 172, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heufel, M.; Kourouche, S.; Mitchell, R.; Cardona, M.; Thomas, B.; Lo, W.A.; Murgo, M.; Vergan, D.; Curtis, K. Development of an Audit Tool to Evaluate End of Life Care in the Emergency Department: A face and content validity study. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2025, 31, e70041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevelyan, E.G.; Robinson, P.N. Delphi methodology in health research: How to do it? Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2015, 7, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, K.; Bernstein, S.; Aguilar, M.D.; Burnand, B. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User’s Manual; RAND: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 0-8330-2918-5. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, J.G.; Maust, D.T.; Myron Chang, M.-U.; Zivin, K.; Gerlach, L.B. Identifying quality indicators for nursing home residents with dementia: A modified Delphi method. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2023, 36, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodyakov, D.; Chen, C. Nature and predictors of response changes in Modified-Delphi panels. Value Health 2020, 23, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.S.B. ABC of content validation and content validity index calculation. Educ. Med. J. 2019, 11, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T.; Owen, S.V. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S.; McKenna, H. Revisiting the Delphi technique—Research thinking and practice: A discussion paper. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2025, 168, 105119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeney, S.; McKenna, H.A.; Hasson, F. The Delphi Technique in Nursing and Health Research, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4051-8754-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, S.W. The Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) Measure: Development and preliminary validation and reliability of an empathy-based consultation process measure. Fam. Pract. 2004, 21, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaii, A.; Mohammadi, E.; Sadooghiasl, A. The meaning of the empathetic nurse-patient communication: A qualitative study. J. Patient Exp. 2021, 8, 23743735211056432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokhour, B.G.; Fix, G.M.; Mueller, N.M.; Barker, A.M.; Lavela, S.L.; Hill, J.N.; Solomon, J.L.; Lukas, C.V. How can healthcare organizations implement patient-centered care? Examining a large-scale cultural transformation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krist, A.H.; Tong, S.T.; Aycock, R.A.; Longo, D.R. Engaging patients in decision-making and behavior change to promote prevention. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2017, 240, 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ystaas, L.M.K.; Nikitara, M.; Ghobrial, S.; Latzourakis, E.; Polychronis, G.; Constantinou, C.S. The impact of transformational leadership in the nursing work environment and patients’ outcomes: A systematic review. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 1271–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Daniel, M.; Rosentein, A. Professional communication and team collaboration. In Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, J.K.; Mullins, R.H.; Penix, E.A.; Roth, K.L.; Trusty, W.T. The importance of listening to patient preferences when making mental health care decisions. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 316–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, V.; Moss, J.; Padgett, N.; Tan, X.; Kennedy, A.B. Attitudes, beliefs and behaviors of religiosity, spirituality, and cultural competence in the medical profession: A cross-sectional survey study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partain, D.K.; Ingram, C.; Strand, J.J. Providing appropriate end-of-life care to religious and ethnic minorities. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swihart, D.L.; Yarrarapu, S.N.S.; Martin, R.L. Cultural religious competence in clinical practice. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tulsky, J.A. Interventions to enhance communication among patients, providers, and families. J. Palliat. Med. 2005, 8, s95–s101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargraves, I.; LeBlanc, A.; Shah, N.D.; Montori, V.M. Shared Decision Making: The need for patient-clinician conversation, not just information. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 627–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, D.; Légaré, F.; Lewis, K.; Barry, M.J.; Bennett, C.L.; Eden, K.B.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Llewellyn-Thomas, H.; Lyddiatt, A.; Thomson, R.; et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Liu, G.; Lu, J.; Xue, D. Association of shared decision making with inpatient satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlich, J.; Matsuoka, K.; Sruamsiri, R. Shared decision making and treatment satisfaction in Japanese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig. Dis. 2017, 35, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, W.S.; Lee, C.-K. Impact of shared-decision making on patient satisfaction. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2010, 43, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.R.; Sobel, D.S.; Ritter, P.L.; Laurent, D.; Hobbs, M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff. Clin. Pract. 2001, 4, 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- King, J.S.; Moulton, B.W. Rethinking informed consent: The case for shared medical decision-making. Am. J. Law. Med. 2006, 32, 429–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenbaum, E. Using informed consent to reduce preventable medical errors. Ann. Health 2012, 21, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Durand, M.-A.; Moulton, B.; Cockle, E.; Mann, M.; Elwyn, G. Can shared decision-making reduce medical malpractice litigation? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J.; Siddiqui, N.; Greenfield, D.; Sharma, A. Kindness, listening, and connection: Patient and clinician key requirements for emotional support in chronic and complex care. J. Patient Exp. 2022, 9, 23743735221092627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, M.J.; Edgman-Levitan, S. Shared decision making—The pinnacle of patient-centered care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 780–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzelepis, F.; Sanson-Fisher, R.; Zucca, A.; Fradgley, E. Measuring the quality of patient-centered care: Why patient-reported measures are critical to reliable assessment. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2015, 9, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Scarinci, N.; Hickson, L. The nature of patient- and family-centred care for young adults living with chronic disease and their family members: A systematic review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E.; Shiraz, F.; Haldane, V.; Koh, J.J.K.; Quek, R.Y.C.; Ozdemir, S.; Finkelstein, E.A.; Jafar, T.H.; Choong, H.-L.; Gan, S.; et al. Biopsychosocial experiences and coping strategies of elderly ESRD patients: A qualitative study to inform the development of more holistic and person-centred health services in Singapore. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasemi, M.; Valizadeh, L.; Zamanzadeh, V.; Keogh, B. A concept analysis of holistic care by hybrid model. Indian. J. Palliat. Care 2017, 23, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzeer, J. Integrating medicine with lifestyle for personalized and holistic healthcare. J. Public Health Emerg. 2023, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirsoy, N. Holistic care philosophy for patient-centered approaches and spirituality. In Patient Centered Medicine; Sayligil, O., Ed.; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-953-51-2991-2. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Weng, R.; Wu, T.; Hsu, C.; Hung, C.; Tsai, Y. The impact of person-centred care on job productivity, job satisfaction and organisational commitment among employees in long-term care facilities. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2967–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattad, P.B.; Pacifico, L. Empowering patients: Promoting patient education and health literacy. Cureus 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharkiya, S.H. Quality communication can improve patient-centred health outcomes among older patients: A rapid review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardavella, G.; Aamli-Gaagnat, A.; Frille, A.; Saad, N.; Niculescu, A.; Powell, P. Top tips to deal with challenging situations: Doctor–patient interactions. Breathe 2017, 13, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickmann, E.; Richter, P.; Schlieter, H. All together now—Patient engagement, patient empowerment, and associated terms in personal healthcare. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, J.; Rankin, D.; Elliott, J. Is consulting patients about their health service preferences a useful exercise? Qual. Health Res. 2013, 23, 876–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgman-Levitan, S.; Schoenbaum, S.C. Patient-centered care: Achieving higher quality by designing care through the patient’s eyes. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2021, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, D.C.; Vieira, I.; Pedro, M.I.; Caldas, P.; Varela, M. Patient satisfaction with healthcare services and the techniques used for its assessment: A systematic literature review and a bibliometric analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Respondent (n = 10) |

|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 5 (50) |

| Female | 5 (50) |

| Age, years | |

| 30–39 | 2 (20) |

| 40–49 | 3 (30) |

| 50–59 | 3 (30) |

| 60–69 | 2 (20) |

| Working period in healthcare | |

| 10–29 years | 5 (50) |

| More than 30 years | 5 (50) |

| Discipline | |

| Medicine | 1 (10) |

| Nursing | 7 (70) |

| Physical Therapy | 2 (20) |

| Institutional affiliation/Occupation | |

| University hospital staff | 1 (10) |

| University staff | 7 (70) |

| JICA consultant | 1 (10) |

| Director of nursing | 1 (10) |

| Educational attainment | |

| Master’s | 1 (10) |

| PhD | 9 (90) |

| Concept | No. | Questions | Median | Min. | Max. | I-CVI | UA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 1 | Interacting with patients with respect as individuals | 8 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| C4 | 39 | Sharing patient decision-making with the care team | 8 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| C6 | 50 | Understanding the person holistically, considering not only their illness but also related physical, psychological, social, cultural, and spiritual aspects | 8 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| C1 | 2 | Communicating with patients to understand their hopes and dreams | 7.5 | 5 | 9 | 0.9 | 0 |

| C5 | 10 | Attempting to understand and communicate what the patient is feeling and communicating | 8 | 5 | 9 | 0.9 | 0 |

| C6 | 17 | Support focused on improving quality of life by leveraging patients’ strengths | 7 | 5 | 8 | 0.9 | 0 |

| C3 | 28 | Providing support based on the treatment needs of patients | 8 | 5 | 9 | 0.9 | 0 |

| C4 | 37 | Empowering patients to make informed decisions | 8 | 5 | 9 | 0.9 | 0 |

| C4 | 40 | Respecting the patient’s choices and decisions regarding their life | 7 | 5 | 9 | 0.9 | 0 |

| C4 | 41 | Providing patients with information about complications and treatment effectiveness | 7.5 | 5 | 9 | 0.9 | 0 |

| C6 | 51 | Supporting patients in living the lives that are right for them | 7.5 | 5 | 9 | 0.9 | 0 |

| C8 | 63 | Continually reviewing the patient’s goals and the plan for achieving those goals | 8 | 5 | 9 | 0.9 | 0 |

| C5 | 5 | Listening carefully to the patient’s experience | 7.5 | 5 | 9 | 0.8 | 0 |

| C1 | 9 | Understanding the intentions of patients and their families through not only their language but also their facial expressions, attitudes, and behaviors | 8 | 5 | 8 | 0.8 | 0 |

| C2 | 13 | Helping patients express their opinions in their care | 7.5 | 3 | 9 | 0.8 | 0 |

| C4 | 36 | Empowering patients to choose treatments that fit their lifestyles and values | 7.5 | 4 | 9 | 0.8 | 0 |

| C5 | 19 | Allowing significant others to participate in providing emotional support to the patient, if necessary | 7 | 5 | 8 | 0.8 | 0 |

| C7 | 56 | Providing information in a way that patients can understand | 7.5 | 3 | 9 | 0.8 | 0 |

| C7 | 57 | Educating patients on how to approach their health challenges in a way that is easy for them to implement | 7 | 5 | 9 | 0.8 | 0 |

| C8 | 59 | Providing prompt and appropriate support according to the patient’s changes and situation | 7 | 5 | 8 | 0.8 | 0 |

| C1 | 3 | Empathizing with the patient’s feelings and providing compassionate care | 8 | 5 | 8 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C8 | 6 | Respecting the patient’s opinion | 7 | 3 | 8 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C2 | 8 | Recognizing patients as persons who have the resources and capabilities to solve their problems | 7 | 3 | 8 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C2 | 11 | Recognizing the patient as a vital member of the care team | 6.5 | 5 | 8 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C2 | 12 | Encouraging patients to participate in their care | 6 | 1 | 8 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C2 | 15 | Deepening the common understanding of the patient’s condition (problem) with the patient and their family | 7 | 5 | 8 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C3 | 24 | Considering the patient’s most important wishes and health concerns | 7 | 1 | 8 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C3 | 29 | Providing care that considers the patient’s values and beliefs | 8 | 3 | 9 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C3 | 31 | Providing support tailored to the patient’s personality and characteristics | 7.5 | 3 | 9 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C8 | 33 | Helping patients find meaning from their illness experiences | 6.5 | 3 | 8 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C4 | 34 | Empowering patients to make decisions for themselves | 7.5 | 4 | 9 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C5 | 45 | Providing comprehensive care to meet the physical, psychological, and social needs of patients | 8 | 2 | 8 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C6 | 49 | Supporting patients with realistic health and life goals | 7 | 3 | 8 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C7 | 52 | Providing patients with information and methods for self-care | 7 | 3 | 8 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C7 | 53 | Talking together with patients about what they can do to improve their health and prevent illness | 7 | 5 | 8 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C7 | 54 | Providing patient-specific education and care | 7 | 3 | 9 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C7 | 55 | Providing patients with adequate and appropriate information | 7 | 3 | 9 | 0.7 | 0 |

| C7 | 20 | Explaining the health condition to the patient and their family in an easy-to-understand manner | 6.5 | 4 | 8 | 0.6 | 0 |

| C3 | 22 | Providing care taking into consideration the patient’s preferences, lifestyle, values, etc. | 6.5 | 3 | 8 | 0.6 | 0 |

| C3 | 25 | Being sensitive to the patient’s concerns, wishes, and priorities | 7 | 2 | 8 | 0.6 | 0 |

| C3 | 27 | Providing care adapted to the patient’s priorities | 7 | 1 | 8 | 0.6 | 0 |

| C3 | 32 | Providing individualized, goal-oriented assistance | 6 | 1 | 8 | 0.6 | 0 |

| C4 | 38 | Providing information to help patients decide what healthcare services they need | 8 | 3 | 9 | 0.6 | 0 |

| C5 | 16 | Helping patients understand what they can do and making them feel more confident | 7 | 5 | 9 | 0.6 | 0 |

| C6 | 47 | Providing care to help patients live comfortably and recover physically | 6 | 3 | 8 | 0.6 | 0 |

| C1 | 7 | Making time to intentionally listen to patients talk | 5.5 | 4 | 9 | 0.5 | 0 |

| C5 | 18 | Providing support to patients with care and consideration for their feelings and situations | 6 | 3 | 8 | 0.5 | 0 |

| C3 | 23 | Understanding the patient’s values and habits | 6 | 3 | 8 | 0.5 | 0 |

| C3 | 30 | Providing care tailored to individual needs | 6 | 3 | 9 | 0.5 | 0 |

| C5 | 43 | Understanding the patient’s emotional needs | 5.5 | 3 | 8 | 0.5 | 0 |

| C5 | 44 | Responding to the patient’s spiritual needs | 5.5 | 3 | 8 | 0.5 | 0 |

| C8 | 58 | Modifying care to suit the patient’s situation, if necessary | 6 | 3 | 8 | 0.5 | 0 |

| C8 | 60 | Responsive and flexible to patient needs | 5.5 | 2 | 8 | 0.5 | 0 |

| C8 | 62 | Paying attention to the patient’s reactions to adapt to their situation at any given time | 4.5 | 3 | 8 | 0.4 | 0 |

| C6 | 46 | Considering the patient’s physical needs | 5 | 3 | 9 | 0.3 | 0 |

| C6 | 48 | Understanding the social needs of patients | 5 | 2 | 8 | 0.3 | 0 |

| C8 | 61 | Adapting to the situation, paying attention to the patient’s reactions (physical reactions, language, and emotional cues) | 5 | 3 | 8 | 0.3 | 0 |

| C7 | 21 | Keeping the patient and their family informed about changes in health status | 4.5 | 3 | 7 | 0.2 | 0 |

| C3 | 26 | Prioritizing the patient’s daily living preferences | 4.5 | 3 | 6 | 0.2 | 0 |

| C4 | 14 | Sharing patient decision-making among the care team | 5 | 5 | 8 | 0.1 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soriano, K.; Nakatani, S.; Onishi, K.; Ito, H.; Nakano, Y.; Takashima, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Blaquera, A.P.; Tanioka, R.; Betriana, F.; et al. Development and Content Validation of a Person-Centered Care Instrument for Healthcare Providers. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15100355

Soriano K, Nakatani S, Onishi K, Ito H, Nakano Y, Takashima Y, Zhao Y, Blaquera AP, Tanioka R, Betriana F, et al. Development and Content Validation of a Person-Centered Care Instrument for Healthcare Providers. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(10):355. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15100355

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoriano, Krishan, Sora Nakatani, Kaito Onishi, Hirokazu Ito, Youko Nakano, Yoshiyuki Takashima, Yueren Zhao, Allan Paulo Blaquera, Ryuichi Tanioka, Feni Betriana, and et al. 2025. "Development and Content Validation of a Person-Centered Care Instrument for Healthcare Providers" Nursing Reports 15, no. 10: 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15100355

APA StyleSoriano, K., Nakatani, S., Onishi, K., Ito, H., Nakano, Y., Takashima, Y., Zhao, Y., Blaquera, A. P., Tanioka, R., Betriana, F., Soriano, G. P., Yasahura, Y., Osaka, K., Kataoka, M., Miyagawa, M., Akaike, M., Irahara, M., & Tanioka, T. (2025). Development and Content Validation of a Person-Centered Care Instrument for Healthcare Providers. Nursing Reports, 15(10), 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15100355