Nursing Students’ Satisfaction with Clinical Simulation: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

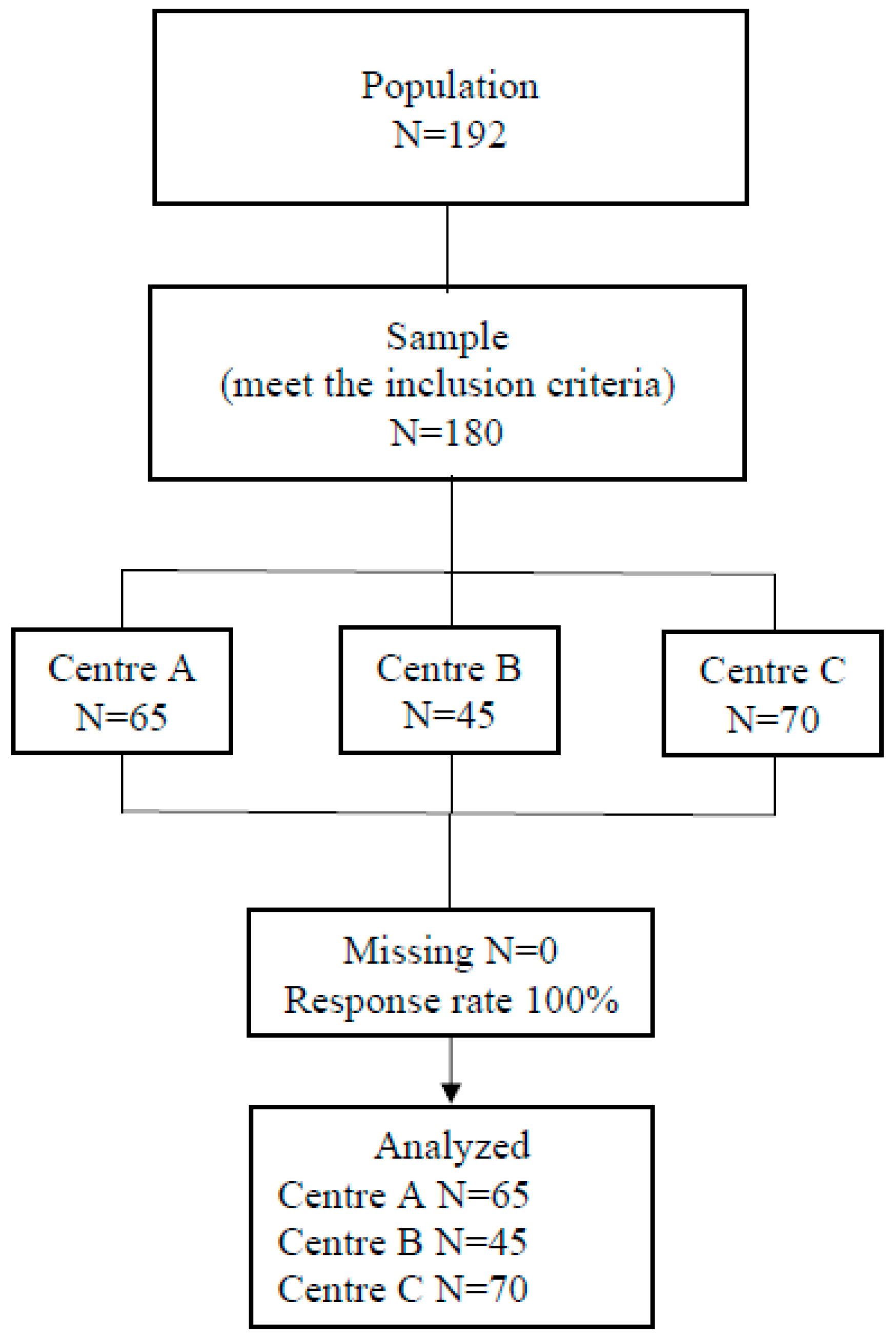

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Students

3.2. Students’ Satisfaction Levels Regarding Clinical Simulation According to the SSHF Items and Factors

3.3. Comparison of the Students’ Satisfaction Levels with Clinical Simulation Across the Different Participating Centres, According to the SSHF Factors

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Torres Escobar, G.A. Medición de la satisfacción estudiantil en universitarios desde el modelo SERVQUAL. RHS-Rev. Humanismo Soc. 2023, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro-López, L.; Hernández-González, P.L.; Hernández-Blas, A.; Hernández-Arzola, L.I. La simulación clínica en la adquisición de conocimientos en estudiantes de la Licenciatura de Enfermería. Enfermería Univ. 2019, 16, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.R.O.; Medeiros, S.M.; Martins, J.C.A.; Coutinho, V.R.D.; Araújo, M.S. Eficacia de la simulación en la enseñanza de inmunización en la enfermería: Ensayo clínico aleatorio. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2020, 28, e3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Repsha, C.; Seo, W.J.; Lee, S.H.; Dahinten, V.S. Room of horrors simulation in healthcare education: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 126, 105824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Arce, A.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Vélez-Vélez, E.; Rodríguez-Gómez, P.; Tovar-Reinoso, A.; Hernández-Martínez, A. Validation of a short version of the high fidelity simulation satisfaction scale in nursing students. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthy, R.; Chitra, F.; Durairaj, K. Traditional teaching method versus simulation-based teaching method in the prevention of medication errors among nursing students. Eur. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 22, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvetto, M.; Pía Bravo, M.; Montaña, R.; Utili, F.; Escudero, E.; Boza, C.; Varas, J.; Dagnino, J. Simulación en educación médica: Una sinopsis. Rev. Médica Chile 2013, 141, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, P.L.; Jenkins, S. Nursing students’ clinical judgement regarding rapid response: The influence of a clinical simulation education intervention. Nursing forum. Wiley Period. 2013, 48, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Maldonado, H.A.; Gallardo Casas, C.Á.; Pérez Elizondo, E. Satisfacción de la simulación clínica como herramienta pedagógica para el aprendizaje en estudiantes de pregrado en Enfermería. Rev. Med. Investig. Univ. Autónoma Estado México 2022, 10, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, Y.; Bryson, E.O.; DeMaria, S.; Jacobson, L.; Quinones, J.; Shen, B.; Levine, A.I. The utility of simulation in medical education: What is the Evidence? Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2009, 76, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrero-Planells, A.; Pol-Castañeda, S.; Alamillos-Guardiola, M.C.; Prieto-Alomar, A.; Tomás-Sánchez, M.; Moreno-Mulet, C. Students and teachers’ satisfaction and perspectives on high-fidelity simulation for learning fundamental nursing procedures: A mixed-method study. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 104, 104981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastón, M.B. Simulación clínica y la pandemia por COVID-19. ¿De dónde venimos? ¿Hacia dónde queremos ir? An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2020, 43, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casal Angulo, M.C.; Fernández-Garrido, J.J.; Ballestar-Tarín, M.L. La Simulación Como Metodol. Para El Aprendiz. De Habilidades No Técnicas En Enfermería. 2016. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/71059825.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Maran, N.J.; Glavin, R.J. Low-to high-fidelity simulation—A continuum of medical education? Med. Educ. 2003, 37, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palés Argullós, J.L.; Gomar Sancho, C. El uso de las simulaciones en educación médica. Educ. Knowl. Soc. 2010, 11, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alconero-Camarero, A.R.; Sarabia-Cobo, C.M.; González-Gómez, S.; Ibáñez-Rementería, I.; Alvarez-García, M.P. Estudio descriptivo de la satisfacción de los estudiantes del Grado en Enfermería en las prácticas de simulación clínica de alta fidelidad. Enfermería Clínica 2020, 30, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenzi, G.; Reuben, A.D.; Díaz Agea, J.L.; Hernández Ruipérez, T.; Leal Costa, C. Self-learning methodology in simulated enviroments (MAES©) utilized in hospital settings. Action-research in an Emergency Department in the United Kingdom. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2022, 61, 101128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Lee, Y.J.; Kang, K.; Park, J. Effectiveness of SBAR-based simulation programs for nursing students: A systematic review. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Sánchez, M.; Ramos López, L.; Pato López, O.; López Álvarez, S. La simulación clínica como herramienta de aprendizaje. Asoc. Española Cirugía Mayor Ambulatoria 2013, 18, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cura, Ş.Ü.; Kocatepe, V.; Yıldırım, D.; Küçükakgün, H.; Atay, S.; Ünver, V. Examining knowledge, skill, stress, satisfaction and self-confidence levels of nursing students in three different simulation modalities. Asian Nurs. Res. 2020, 14, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbers, J.; Rossman, C. Satisfaction and self-confidence with nursing clinical simulation: Novice learners, medium-fidelity, and community settings. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 48, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, R.; Shor, V.; Kimhi, E. The influence of simulated medication administration learning on the clinical performance of nursing students: A comparative quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 103, 104947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdemir, N.G.; Kaya, H. The effectiveness of high-fidelity simulation methods to gain Foley catheterization knowledge, skills, satisfaction and self-confidence among novice nursing students: A randomized controlled trial. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 130, 105952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chagas Rosa, M.E.; Vieira Pereira-Ávila, F.M.; Bezerra Góes, F.G.; Vieira Pereira-Ávila, N.M.; Milanês Sousa, L.R.; Lemos Goulart, M.C. Positive and negative aspects of clinical simulation in nursing teaching. Esc Anna Nery 2020, 24, e20190353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez López, F. La Simulación Clínica Como Herramienta de Aprendizaje en Estudiantes de Medicina. 2023. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10803/689783 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Álvarez Botello, J.; Chaparro Salinas, E.M.; Reyes Pérez, D.E. Estudio de la satisfacción de los estudiantes con los servicios educativos brindados por las instituciones de educación superior del Valle de Toluca. Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2014, 13, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Ortiz, Y.A.; Mejías Acosta, A. Factores que determinan la satisfacción estudiantil en educación superior: Análisis de caso en una universidad colombiana. Ing. Soc. 2018, 13, 162–172. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez Castillo, M. Adaptación de la Escala de Satisfacción en Simulación de Alta Fidelidad en Estudiantes de Enfermería. 2021. Available online: https://repositorioslatinoamericanos.uchile.cl/handle/2250/3545004 (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Jiménez González, A.; Terriquez Carrillo, B.; Robles Zepeda, F.J. Evaluación de la satisfacción académica de los estudiantes de la Universidad autónoma de Nayarit. Fuente 2011, 3, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, J.; Buyl, R.; D’haenens, F.; Swinnen, E.; Stas, L.; Gucciardo, L.; Fobelets, M. Midwifery students’ satisfaction with perinatal simulation-based training. Women Birth 2021, 34, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Au, M.L.; Tong, L.K.; Ng, W.I.; Wang, S.C. High-fidelity simulation in undergraduate nursing education: A meta-analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 111, 105291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaussen, C.; Heggdal, K.; Tvedt, C.R. Elements in scenario-based simulation associated with nursing students’ self-confidence and satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Open 2019, 7, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabañero-Martinez, M.J.; García-Sanjuán, S.; Escribano, S.; Fernández-Alcántara, M.; Martínez-Riera, J.R.; Juliá-Sanchís, R. Mixed-method study on the satisfaction of a high-fidelity simulation program in a sample of nursing-degree students. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 100, 104858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, K.; Alharbi, M.F. Nursing Students’ Satisfaction and Self-Confidence Levels After Their Simulation Experience. SAGE Open Nurs. 2022, 8, 23779608221139080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ming Chow, K.; Ahmat, R.; Leung, A.W.Y.; Chan, C.W.H. Is high-fidelity simulation-based training in emergency nursing effective in enhancing clinical decision-making skills? A mixed methods study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 69, 103610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez Rodríguez, J.R.; Calderón Calderón, M.S.; Vargas Díaz, A.A.; Espino Ruiz, D.A.; Castillo de Lemus, R.M.; González Williams, Y.M. Experiencia formativa de académicos en dos universidades latinas en diplomado de simulación clínica en enfermería. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-03192023000100023&lng=es&tlng=es (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Orden CIN/2134/2008; De 3 de Julio, por la que se Establecen los Requisitos para la Verificación de los Títulos Universitarios Oficiales que Habiliten para el Ejercicio de la Profesión de Enfermero. Boletín Oficial del Estado 174: Spain; 2008. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/o/2008/07/03/cin2134 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Alconero-Camarero, A.R.; Gualdrón-Romero, A.; Sarabia-Cobo, C.M.; Martínez-Arce, A. Clinical simulation as a learning tool in undergraduate nursing: Validation of a questionnaire. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 39, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alconero-Camarero, A.R.; Sarabia-Cobo, C.M.; Catalán-Piris, M.J.; González-Gómez, S.; González-López, J.R. Nursing Students’ Satisfaction: A Comparison between Medium- and High-Fidelity Simulation Training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrogante, O.; González-Romero, G.M.; Carrión-García, L.; Polo, A. Reversible causes of cardiac arrest: Nursing competency acquisition and clinical simulation satisfaction in undergraduate nursing students. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2021, 54, 100938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrogante, O.; González-Romero, G.M.; López-Torre, E.M.; Carrión-García, L.; Polo, A. Comparing formative and summative simulation-based assessment in undergraduate nursing students: Nursing competency acquisition and clinical simulation satisfaction. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Rodríguez, D.; Arrogante, O. Simulated Video Consultations as a Learning Tool in Undergraduate Nursing: Students’ Perceptions. Healthcare 2020, 8, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Seville. Memoria de Verificación: Título Oficial de Graduado o Graduada en Enfermería por la Universidad de Sevilla; University of Seville: Sevilla, Spain, 2008; Available online: https://alojawebapps.us.es/fichape/Doc/MV/157_memverif.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Cea D’Ancona, M.A. Metodología Cuantitativa. Estrategias y Técnicas de Investigación Social; Síntesis: La Habana, Cuba, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Fernández-Collado, C.; Baptista-Lucio, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Mexico City, México, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. 2013. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Baptista, R.C.N.; Paiva, L.A.R.; Gonçalves, R.F.L.; Oliveira, L.M.N.; Pereira, M.F.C.R.; Martins, J.C.A. Satisfaction and gains perceived by nursing students with medium and high-fidelity simulation: A randomized controlled trial. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 46, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Cámara, S.; da-Silva-Domingues, H.; Parra-Anguita, L.; Gutiérrez-Sánchez, B. Evaluating Satisfaction and Self-Confidence among Nursing Students in Clinical Simulation Learning. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, D.M.; Vargas, J.L. Uso de la Simulación Clínica en Cuidado Intensivo como Estrategia Pedagógica para el Desarrollo de Habilidades Integrales en Estudiantes de Enfermería y Medicina. 2022. Available online: https://repository.javeriana.edu.co/handle/10554/60138 (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Vargas-Ovalle, J.L.; Franco-Sánchez, D.M. Simulación clínica en cuidado intensivo como herramienta para el desarrollo de habilidades no técnicas en profesionales de la salud. Simulación Clín. 2023, 5, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.; Rossi, D.; Anastasi, J.; Gray-Ganter, G.; Tennent, R. Indicators of undergraduate nursing students’ satisfaction with their learning journey: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 43, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astudillo-Araya, Á.; López-Espinoza, M.Á.; Cádiz-Medina, V.; Fierro-Palma, J.; Figueroa-Lara, A.; Vilches-Parra, N. Validación de la encuesta de calidad y satisfacción de simulación clínica en estudiantes de enfermería. Cienc. Enfermería 2017, 23, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsley, T.L.; Bensfield, L.A.; Sojka, S.; Schmitt, A. Multiple-Patient Simulations: Guidelines and Examples. Nurse Educ. 2014, 39, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INACSL Standards Committee. Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice TM Prebriefing: Preparation and Briefing. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2021, 58, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Vera, P.I.; Martini, J.G. Satisfacción de estudiantes de enfermería con práctica de simulación clínica en escenarios de alta fidelidad. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2020, 29, e20190348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, T.A. Assessing the Impact of Simulation Role on Anxiety and Perceived Outcomes in Undergraduate Nursing Students. Available online: https://kb.gcsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1025&context=dnp (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Boostel, R.; Felix, J.V.C.; Pedrolo, E.; Vayego, S.A.; Mantovani, M.F. Estresse do estudante de enfermagem na simulação clínica: Ensaio clínico randomizado. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018, 71, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanié, A.; Gorse, S.; Roulleau, P.; Figueiredo, S.; Benhamou, D. Impact of learners’ role (active participant-observer or observer only) on learning outcomes during high-fidelity simulation sessions in anaesthesia: A single center, prospective and randomised study. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2018, 37, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiz Camacho, H. La práctica de la simulación clínica en las ciencias de la salud. Rev. Colomb. Cardiol. 2011, 18, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manterola, C.; Otzen, T. Checklist for reporting results using observational descriptive studies as research designs. The MInCirs initiative. Int. J. Morphol. 2017, 35, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Conceptual Definition | Items |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Simulation utility | Suitability of CS as a tool that eases learning. | 7: Simulation is useful to assess the clinical status of a patient. 10: Simulation will improve my ability to provide care to my patients. 12: Simulation will improve communication and the ability to work with the team. 15: Simulation allows us to plan patient’s care effectively. 16: Simulation will improve my technical skills. 17: Simulation will reinforce my critical thinking and decision-making. 18: Simulation will help me assess the patient’s condition. 19: This experience will help me prioritize care. 21: Simulation improves communication with the team. 22: It improves communication with the family. 23: It improves communication with the patient. 26: Simulation will improve my clinical competence. 31: Simulation will allow me to learn from the mistakes I made. |

| 2. Characteristics of cases and applications | Suitability of the clinical settings developed in relation to the students’ own characteristics. | 2: Are the simulation objectives clear? 5: The degree of difficulty of the cases is adequate to my knowledge. 6: I felt comfortable and respected during the sessions. 8: Simulation practice lets you learn how to avoid making mistakes. |

| 3. Communication | Communication tasks that are carried out while developing CS sessions. | 27: The teacher always gives constructive feedback after each simulation session. 28: Debriefing at the end of the session allows reflecting on the cases. 29: Debriefing at the end of the session helps to correct mistakes. |

| 4. Self-reflection on performance | CS application in clinical practices. | 9: Simulation will help me set priorities for action in clinical situations. 11: Simulation will make me think about my next clinical practice. 32: Simulation is useful in the practice. |

| 5. self-confidence | Repercussion level of the CS sessions on the students’ self-confidence. | 20: Simulation promotes self-confidence. 24: Simulation will improve my self-confidence. 33: I will meet my learning expectations with these sessions. |

| 6. Relation between theory and practice | The ability of CS to act as a bridge between theoretical and practical knowledge. | 3: Do the cases recreate real situations? 4: Is timing for each simulation case adequate? 14: Simulation is helpful as it relates theory with practice. |

| 7. Facilities and equipment | CS and the students’ ability to create an immersive clinical setting. | 1: Do you think that the simulation classrooms where the cases are developed are real? 25: Yom can “lose your cool” with some cases during the simulation sessions. 30: I already know the theoretical part of the cases. |

| 8. Negative aspects of simulation | Characteristics of CS that might suppose negative repercussions. | 13: Simulation will make me more worried about the competences that a graduated nurse should have. |

| Centres | Mean Age (Standard Deviation) | Age Range | % of Women (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centre A | 22.75 (4.84) | 19–40 | 92.31 (60) |

| Centre B | 21.74 (2.57) | 20–33 | 89.13 (41) |

| Centre C | 21.94 (1.48) | 20–25 | 88.57 (62) |

| Items | N (%) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire Sample | Centre A | Centre B | Centre C | ||||||||||

| S. 1 y 2 | S. 3 | S. 4 y 5 | (SD) | S. 1 y 2 | S. 3 | S. 4 y 5 | S. 1 y 2 | S. 3 | S. 4 y 5 | S. 1 y 2 | S. 3 | S. 4 y 5 | |

| 1 | 41 (22.78) | 19 (10.56) | 120 (66.67) | 3.57 (±0.98) | 10 (15.38) | 2 (3.308) | 53 (81.54) | 18 (40) | 7 (15.56) | 20 (44.44) | 13 (18.57) | 10 (14.29) | 47 (67.15) |

| 2 | 4 (2.22) | 19 (10.56) | 157 (87.22) | 4.1 (±0.66) | 3 (4.61) | 9 (13.85) | 53 (81.54) | 1 (2.22) | 3 (6.66) | 41 (91.11) | 0 (0) | 7 (10) | 63 (90) |

| 3 | 20 (11.17) | 25 (13.89) | 134 (74.86) | 3.94 (±0.99) | 7 (10.77) | 5 (7.69) | 53 (81.54) | 9 (20) | 7 (15.56) | 29 (64.45) | 4 (5.71) | 12 (17.14) | 53 (75.71) |

| 4 | 107 (60.11) | 21 (11.67) | 50 (28.09) | 2.62 (±1.1) | 38 (58.46) | 5 (7.69) | 21 (32.31) | 21 (46.66) | 12 (26.67) | 11 (24.44) | 44 (62.86) | 4 (5.71) | 22 (31.43) |

| 5 | 10 (5.62) | 33 (18.33) | 135 (75.84) | 3.89 (±0.79) | 3 (4.61) | 11 (16.92) | 51 (58.46) | 2 (4.44) | 6 (13.33) | 36 (80) | 5 (7.14) | 16 (22.86) | 49 (70) |

| 6 | 0 (0) | 12 (6.67) | 168 (93.33) | 4.42 (±0.61) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.08) | 63 (96.92) | 0 (0) | 5 (11.11) | 40 (88.89) | 0 (0) | 5 (7.14) | 65 (92.86) |

| 7 | 23 (12.78) | 22 (12.22) | 135 (75) | 3.92 (±1.04) | 8 (12.31) | 9 (13.85) | 48 (73.85) | 8 (17.77) | 7 (15.56) | 30 (66.67) | 7 (10) | 5 (7.14) | 58 (82.86) |

| 8 | 42 (23.33) | 36 (20) | 102 (56.67) | 3.45 (±1.1) | 19 (29.23) | 10 (15.38) | 36 (55.39) | 8 (17.78) | 10 (22.22) | 27 (60) | 14 (20) | 16 (22.86) | 40 (57.14) |

| 9 | 11 (6.11) | 23 (12.78) | 146 (81.11) | 4.04 (±0.87) | 8 (12.3) | 8 (12.31) | 49 (75.38) | 2 (4.44) | 8 (17.78) | 35 (77.78) | 1 (1.43) | 6 (8.57) | 63 (90) |

| 10 | 13 (7.22) | 21 (11.67) | 146 (81.11) | 4.04 (±0.9) | 7 (10.76) | 9 (13.85) | 49 (75.38) | 2 (4.44) | 8 (17.78) | 35 (77.78) | 4 (5.71) | 4 (5.71) | 62 (88.57) |

| 11 | 11 (6.11) | 20 (11.11) | 149 (82.78) | 4.04 (±0.84) | 5 (7.69) | 5 (7.69) | 55 (84.61) | 1 (2.22) | 5 (11.11) | 39 (86.67) | 5 (7.14) | 10 (14.29) | 55 (78.57) |

| 12 | 17 (9.44) | 28 (15.56) | 135 (75) | 3.84 (±0.87) | 10 (15.39) | 7 (10.77) | 48 (73.84) | 6 (13.33) | 11 (24.44) | 28 (62.23) | 1 (1.43) | 9 (12.86) | 60 (85.71) |

| 13 | 16 (8.94) | 27 (1) | 136 (75.98) | 3.99 (±0.96) | 8 (12.31) | 17 (26.15) | 39 (60) | 4 (8.88) | 5 (11.11) | 36 (80) | 4 (5.71) | 4 (5.71) | 62 (88.57) |

| 14 | 1 (0.56) | 9 (5) | 168 (94.38) | 4.4 (±0.61) | 0 (0) | 4 (6.15) | 61 (93.85) | 0 (0) | 4 (8.89) | 41 (91.11) | 1 (1.43) | 1 (1.43) | 66 (94.29) |

| 15 | 17 (9.6) | 40 (22.22) | 120 (67.8) | 3.74 (±0.86) | 6 (9.23) | 16 (24.62) | 40 (61.53) | 6 (13.33) | 8 (17.78) | 31 (68.89) | 5 (7.14) | 16 (22.86) | 49 (70) |

| 16 | 20 (11.17) | 28 (15.56) | 131 (73.18) | 3.9 (±0.96) | 9 (13.85) | 7 (10.77) | 48 (73.84) | 5 (11.11) | 10 (22.22) | 30 (66.67) | 6 (8.57) | 11 (15.71) | 53 (75.71) |

| 17 | 11 (6.21) | 28 (15.56) | 138 (77.97) | 3.93 (±0.81) | 8 (12.31) | 14 (21.54) | 41 (63.08) | 2 (4.44) | 4 (8.89) | 39 (86.67) | 1 (1.43) | 9 (12.86) | 59 (84.28) |

| 18 | 29 (16.2) | 39 (21.6) | 111 (62.01) | 3.63 (±0.97) | 13 (20) | 16 (24.62) | 35 (53.85) | 7 (15.56) | 10 (22.22) | 28 (62.22) | 8 (11.43) | 13 (18.57) | 49 (70) |

| 19 | 14 (7.82) | 34 (18.89) | 131 (73.18) | 3.87 (±0.85) | 8 (12.31) | 16 (24.62) | 40 (61.54) | 4 (8.89) | 6 (13.33) | 35 (77.78) | 2 (2.86) | 11 (15.71) | 57 (81.69) |

| 20 | 18 (10.06) | 37 (20.56) | 124 (69.27) | 3.84 (±0.95) | 7 (10.77) | 13 (20) | 44 (67.69) | 9 (20) | 10 (22.22) | 26 (57.77) | 2 (2.86) | 14 (20) | 54 (77.15) |

| 21 | 21 (11.67) | 40 (22.22) | 119 (66.11) | 3.78 (±0.99) | 12 (18.46) | 13 (20) | 40 (61.54) | 5 (11.11) | 13 (28.89) | 27 (60) | 3 (4.29) | 14 (20) | 53 (75.71) |

| 22 | 66 (36.67) | 67 (37.22) | 47 (26.11) | 2.82 (±1.09) | 21 (32.31) | 28 (43.08) | 16 (24.61) | 16 (35.55) | 18 (40) | 11 (24.44) | 28 (40) | 21 (30) | 21 (30) |

| 23 | 52 (29.71) | 50 (27.78) | 73 (41.71) | 3.13 (±1.07) | 19 (29.23) | 24 (36.92) | 21 (32.31) | 14 (31.1) | 12 (26.67) | 17 (37.78) | 19 (27.14) | 13 (18.57) | 36 (51.43) |

| 24 | 23 (13.07) | 35 (19.44) | 118 (67.05) | 3.77 (±1) | 11 (16.93) | 11 (16.92) | 43 (66.16) | 8 (17.78) | 10 (22.22) | 25 (55.56) | 4 (5.71) | 14 (20) | 50 (71.43) |

| 25 | 26 (14.77) | 26 (14.44) | 124 (70.45) | 3.77 (±1.02) | 11 (16.93) | 16 (24.62) | 38 (58.46) | 10 (22.22) | 6 (13.33) | 27 (60) | 5 (7.14) | 4 (5.71) | 59 (84.28) |

| 26 | 9 (5.14) | 18 (10) | 148 (84.57) | 4.01 (±0.72) | 4 (6.15) | 8 (12.31) | 53 (81.54) | 4 (8.89) | 3 (6.66) | 35 (77.78) | 1 (1.43) | 7 (10) | 60 (85.71) |

| 27 | 18 (10.23) | 26 (14.44) | 132 (75) | 3.83 (±0.9) | 5 (7.69) | 13 (20) | 47 (72.31) | 9 (20) | 9 (20) | 25 (55.56) | 4 (5.71) | 4 (5.71) | 60 (85.71) |

| 28 | 6 (3.41) | 55 (30.56) | 115 (65.34) | 3.74 (±0.71) | 2 (3.08) | 18 (27.69) | 45 (69.23) | 3 (6.66) | 18 (40) | 22 (48.89) | 1 (1.43) | 19 (27.14) | 48 (68.57) |

| 29 | 8 (4.57) | 40 (22.22) | 127 (72.57) | 3.86 (±0.76) | 5 (7.69) | 8 (12.31) | 52 (80) | 2 (4.44) | 16 (35.56) | 25 (55.56) | 1 (1.43) | 16 (22.86) | 50 (71.43) |

| 30 | 18 (10.23) | 28 (15.56) | 130 (73.86) | 3.83 (±0.91) | 3 (4.61) | 12 (18.46) | 50 (76.92) | 5 (11.11) | 5 (11.11) | 33 (73.33) | 10 (14.29) | 11 (15.71) | 47 (67.14) |

| 31 | 4 (2.29) | 8 (4.44) | 163 (93.14) | 4.21 (±0.66) | 3 (4.62) | 4 (6.15) | 58 (89.23) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.44) | 41 (91.11) | 1 (1.43) | 2 (2.86) | 64 (91.43) |

| 32 | 8 (4.57) | 14 (7.78) | 153 (87.43) | 4.18 (±0.83) | 4 (6.16) | 9 (13.85) | 52 (80) | 3 (6.67) | 2 (4.44) | 37 (82.22) | 1 (1.43) | 3 (4.29) | 64 (91.43) |

| 33 | 18 (10.23) | 28 (15.56) | 130 (73.86) | 3.88 (±0.93) | 7 (10.77) | 11 (16.92) | 47 (72.31) | 10 (22.22) | 7 (15.56) | 26 (57.78) | 1 (1.43) | 10 (14.29) | 57 (81.43) |

| Factors | Arithmetic Mean ± SD [Median/Interquartile Range] of the Items | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Centre A | Centre B | Centre C | |

| Factor 1. Simulation utility | 3.57 ± 0.71 [4.0/1.0] | 3.62 ± 0.59 [4.0/1.0] | 3.9 ± 0.55 [4.0/1.0] |

| Factor 2. Characteristics of cases and applications | 3.88 ± 0.61 [4.0/1.0] | 3.9 ± 0.47 [4.0/0.0] | 4.06 ± 0.55 [4.0/1.0] |

| Factor 3. Communication | 3.79 ± 0.57 [4.0/1.0] | 3.39 ± 1.05 [4.0/1.0] | 3.86 ± 0.91 [4.0/1.0] |

| Factor 4. Self-reflection on performance | 3.97 ± 0.75 [4.0/1.0] | 3.93 ± 0.70 [4.0/1.0] | 4.2 ± 0.65 [4.0/1.0] |

| Factor 5. Increased self-confidence | 3.76 ± 0.85 [4.0/2.0] | 3.41 ± 0.84 [4.0/1.0] | 4 ± 0.85 [4.0/1.0] |

| Factor 6. Relation between theory and practise | 3.6 ± 0.69 [4.0/2.0] | 3.53 ± 0.68 [4.0/1.0] | 3.7 ± 0.60 [4.0/1.0] |

| Factor 7. Facilities and equipment | 3.79 ± 0.66 [4.0/1.0] | 3.35 ± 0.75 [4.0/2.0] | 3.75 ± 0.72 [4.0/1.0] |

| Factor 8. Negative aspects of simulation | 3.65 ± 1.06 [4.0/1.0] | 3.87 ± 0.86 [4.0/0.0] | 4.34 ± 0.83 [4.5/1.0] |

| Factors | Centre | Average Range | Statistical | p | Contrast | Sig. | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Simulation utility | A | 80.446 | 9.0582 | 0.0107 | A–B | - | −1.842 |

| B | 82.288 | A–C | * | −24.668 | |||

| C | 105.114 | B–C | - | −22.825 | |||

| 2. Characteristics of cases and applications | A | 85.2 | 3.5348 | 0.1707 | A–B | - | 1.111 |

| B | 84.088 | A–C | - | −14.342 | |||

| C | 99.542 | B–C | - | −15.454 | |||

| 3. Communication | A | 91.130 | 8.4702 | 0.0144 | A–B | - | 18.319 |

| B | 72.811 | A–C | - | −10.154 | |||

| C | 101.286 | B–C | * | −28.474 | |||

| 4. Self-reflection on performance | A | 84.092 | 7.0577 | 0.0293 | A–B | - | 3.847 |

| B | 80.244 | A–C | - | −18.950 | |||

| C | 103.043 | B–C | - | −22.798 | |||

| 5. Self-confidence | A | 89.938 | 13.7326 | 0.0010 | A–B | - | 21.371 |

| B | 68.566 | A–C | - | −15.183 | |||

| C | 105.121 | B–C | * | −36.554 | |||

| 6. Relation between theory and practise | A | 88.315 | 1.2691 | 0.5301 | A–B | - | 2.815 |

| B | 85.5 | A–C | - | −7.427 | |||

| C | 95.742 | B–C | - | −10.242 | |||

| 7. Facilities and equipment | A | 97.853 | 12.1461 | 0.0023 | A–B | * | 30.476 |

| B | 67.377 | A–C | - | −0.681 | |||

| C | 98.535 | B–C | * | −31.157 | |||

| 8. Negative aspects of simulation | A | 75.593 | 17.8198 | 0.0001 | A–B | - | −5.339 |

| B | 80.933 | A–C | * | −33.406 | |||

| C | 109.0 | B–C | * | −28.066 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Álvarez, J.A.; Guerra-Martín, M.D.; Borrallo-Riego, Á. Nursing Students’ Satisfaction with Clinical Simulation: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3178-3190. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040231

Jiménez-Álvarez JA, Guerra-Martín MD, Borrallo-Riego Á. Nursing Students’ Satisfaction with Clinical Simulation: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(4):3178-3190. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040231

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Álvarez, Juan Antonio, María Dolores Guerra-Martín, and Álvaro Borrallo-Riego. 2024. "Nursing Students’ Satisfaction with Clinical Simulation: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study" Nursing Reports 14, no. 4: 3178-3190. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040231

APA StyleJiménez-Álvarez, J. A., Guerra-Martín, M. D., & Borrallo-Riego, Á. (2024). Nursing Students’ Satisfaction with Clinical Simulation: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Nursing Reports, 14(4), 3178-3190. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040231