Why Are Healthcare Providers Leaving Their Jobs? A Convergent Mixed-Methods Investigation of Turnover Intention among Canadian Healthcare Providers during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

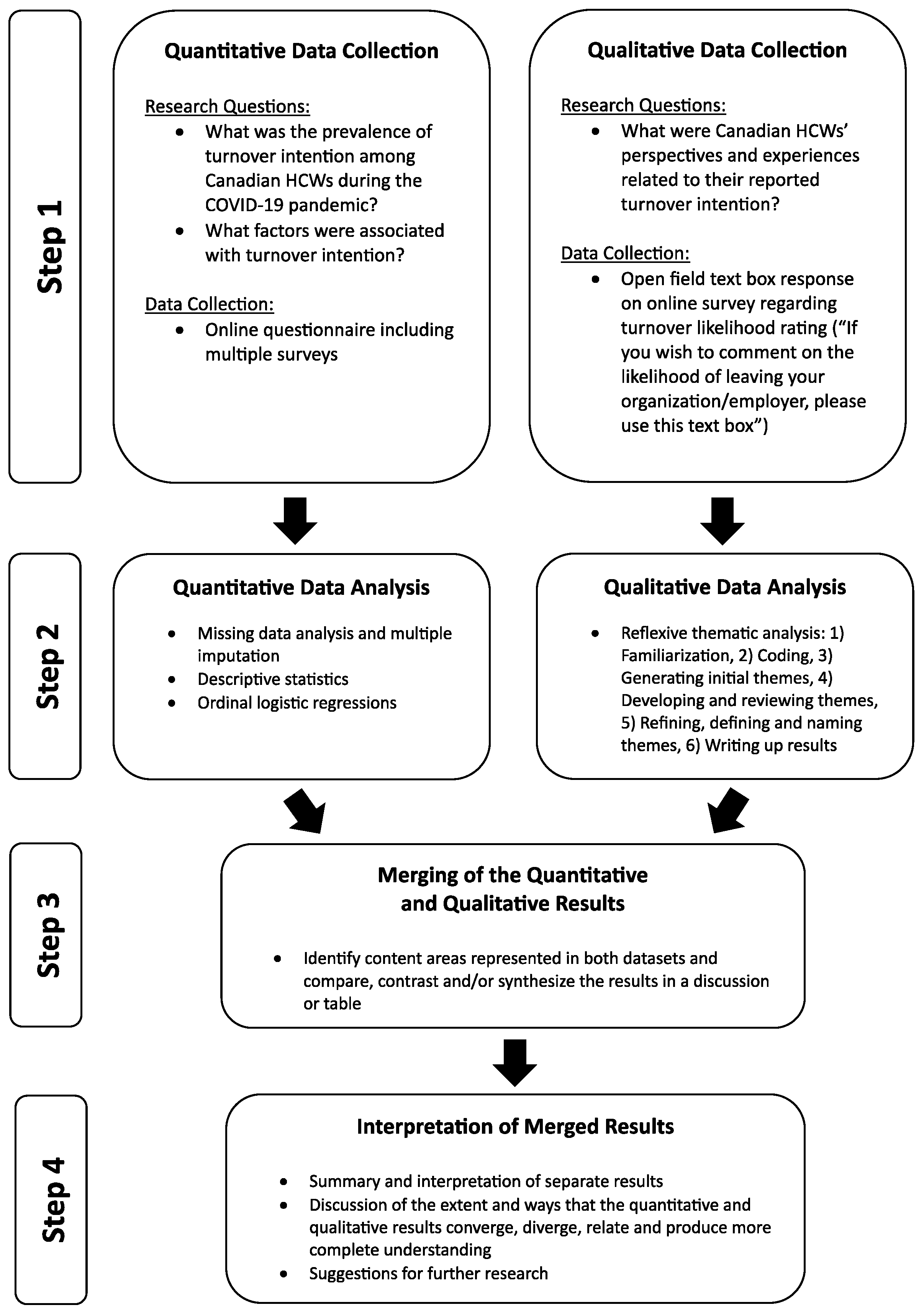

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis

Data Preparation and Analysis

2.4. Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Data

3.1.1. Sample

3.1.2. Turnover Intention—Organization

3.1.3. Turnover Intention—Profession

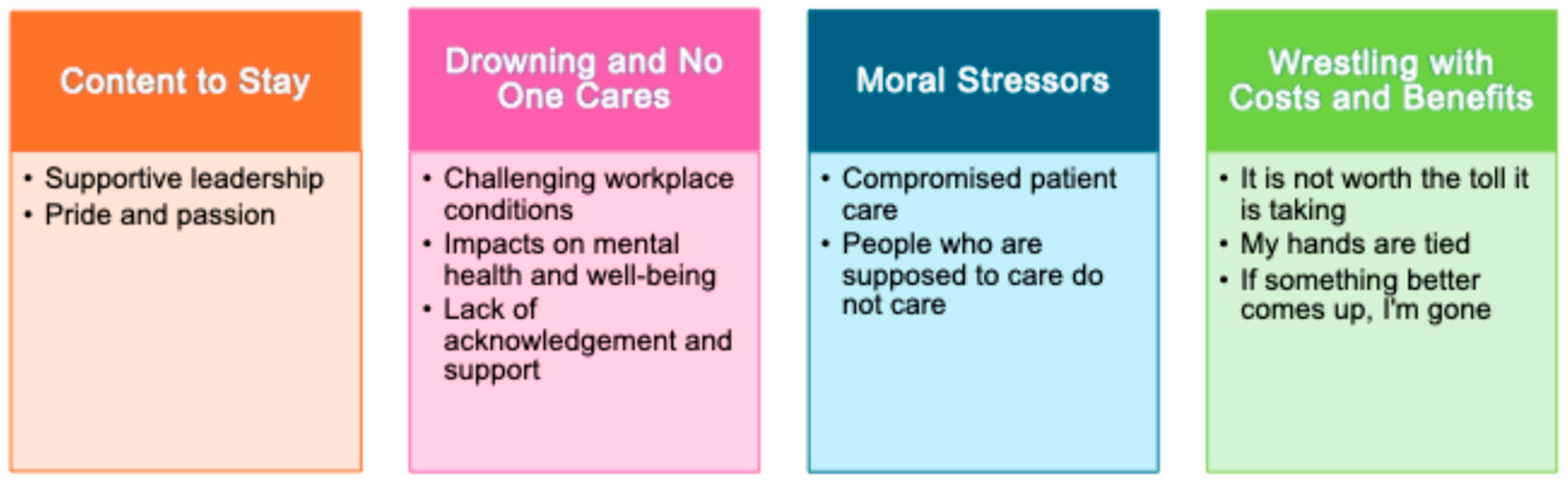

3.2. Qualitative Data

3.2.1. Content to Stay

3.2.2. Supportive Leadership

3.2.3. Pride and Passion

3.2.4. Drowning and No One Cares

3.2.5. Challenging Workplace Conditions

3.2.6. Impacts on Mental Health and Well-Being

3.2.7. Lack of Acknowledgment and Support

3.2.8. Moral Stressors

3.2.9. Compromised Patient Care

3.2.10. People Who Are Supposed to Care Do Not Care

3.2.11. Wrestling with the Costs and Benefits

3.2.12. It Is Not Worth the Toll It Is Taking

“If something doesn’t change, I’m leaving the industry to go where I am valued and not worked to death” (P262).

“I can retire in about a year and if work life balance does not improve, which I’m hoping it will, I will seriously consider retiring early” (P206)

“I’d like to be part time, I am just returning from a stress leave and being in the emergency department or maybe just healthcare in general seems unsustainable” (P353).

“I have experienced significant mental and physical health problems exacerbated by my role, and I don’t know how much longer I can continue in this job. I may leave the profession” (P370).

3.2.13. My Hands Are Tied

3.2.14. If Something Better Comes Up, I Am Gone

“If a better job came up in a private setting, then yes, I would. With the hope of being valued” (P199).

“If a comparable role and compensation was available outside of LTC I would consider a change” (P20).

“If I get a job closer to home in my field I will consider” (P21).

“I would leave immediately if I could find something comparable in terms of job security, pension, benefits and wage” (P279).

3.3. Merged Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Quantitative Results

4.2. Summary of Qualitative Findings

4.3. Interpretation of Merged Results

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Canada. Job Vacancies, Second Quart 2023. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/230919/dq230919b-eng.htm (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Nikkhah-Farkhani, Z.; Piotrowski, A. Nurses’ Turnover Intention a Comparative Study between Iran and Poland. Med. Pr. 2020, 71, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, S.J.; Richter, J.P.; Beauvais, B. The Effects of Nursing Satisfaction and Turnover Cognitions on Patient Attitudes and Outcomes: A Three-Level Multisource Study. Health Serv. Res. 2018, 53, 4943–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.; Lee, N.J.; Kim, E.Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, K.; Park, K.O.; Sung, Y.H. Nurse Staffing Level and Overtime Associated with Patient Safety, Quality of Care, and Care Left Undone in Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 60, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.W.; Chen, W.Y.; Lee, J.L.; Huang, L.C. Nurse Staffing, Direct Nursing Care Hours and Patient Mortality in Taiwan: The Longitudinal Analysis of Hospital Nurse Staffing and Patient Outcome Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falatah, R. The Impact of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic on Nurses’ Turnover Intention: An Integrative Review. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 787–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, Y.S.R.; Lin, Y.P.; Griffiths, P.; Yong, K.K.; Seah, B.; Liaw, S.Y. A Global Overview of Healthcare Workers’ Turnover Intention amid COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review with Future Directions. Hum. Resour. Health 2022, 20, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebregziabher, D.; Berhanie, E.; Berihu, H.; Belstie, A.; Teklay, G. The Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention among Nurses in Axum Comprehensive and Specialized Hospital Tigray, Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2020, 19, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro-Lowe, A.M.; Ritchie, K.; Brown, A.; Easterbrook, B.; Xue, Y.; Pichtikova, M.; Altman, M.; Beech, I.; Millman, H.; Foster, F.; et al. Canadian Respiratory Therapists Who Considered Leaving Their Clinical Position Experienced Elevated Moral Distress and Adverse Psychological and Functional Outcomes during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2023, 43, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie-Tremblay, M.; Gélinas, C.; Aubé, T.; Tchouaket, E.; Tremblay, D.; Gagnon, M.P.; Côté, J. Influence of Caring for COVID-19 Patients on Nurse’s Turnover, Work Satisfaction and Quality of Care. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrișor, C.; Breazu, C.; Doroftei, M.; Mărieș, I.; Popescu, C. Association of Moral Distress with Anxiety, Depression, and an Intention to Leave among Nurses Working in Intensive Care Units during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronda, D.C.; Labrague, L.J. Turnover Intention and Coronaphobia among Frontline Nurses during the Second Surge of COVID-19: The Mediating Role of Social Support and Coping Skills. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schug, C.; Geiser, F.; Hiebel, N.; Beschoner, P.; Jerg-Bretzke, L.; Albus, C.; Weidner, K.; Morawa, E.; Erim, Y. Sick Leave and Intention to Quit the Job among Nursing Staff in German Hospitals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.; King, R.; Senek, M.; Robertson, S.; Taylor, B.; Tod, A.; Ryan, A. UK Advanced Practice Nurses’ Experiences of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Methods Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameddine, M.; Bou-Karroum, K.; Hijazi, M.A. A National Study on the Resilience of Community Pharmacists in Lebanon: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2022, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashwan, A.J.; Abujaber, A.A.; Villar, R.C.; Nazarene, A.; Al-Jabry, M.M.; Fradelos, E.C. Comparing the Impact of COVID-19 on Nurses’ Turnover Intentions before and during the Pandemic in Qatar. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, A.M.; Ritchie, K.; McCabe, R.E.; Lanius, R.A.; Heber, A.; Smith, P.; Ma-lain, A.; Schielke, H.; O’Connor, C.; Hosseiny, F.; et al. Healthcare Workers and COVID-19-Related Moral Injury: An Interpersonally-Focused Approach Informed by PTSD. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 784523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Lopes, J.; Ritchie, K.; D’Alessandro, A.M.; Banfield, L.; McCabe, R.E.; Heber, A.; Lanius, R.A.; McKinnon, M.C. Potential Circumstances Associated with Moral Injury and Moral Distress in Healthcare Workers and Public Safety Personnel across the Globe during COVID-19: A Scoping Review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, P.L.; Kreh, A.; Kulcar, V.; Lieber, A.; Juen, B. A Scoping Review of Moral Stressors, Moral Distress and Moral Injury in Healthcare Workers during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, K.; D’Alessandro-Lowe, A.M.; Brown, A.; Millman, H.; Pichtikova, M.; Xue, Y.; Altman, M.; Beech, I.; Karram, M.; Hoisseny, F.; et al. The Hidden Crisis: Understanding Potentially Morally Injurious Events Experienced by Healthcare Providers during COVID-19 in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, J.T.; Keith, M.M.; Hurley, M.; McArthur, J.E. Sacrificed: Ontario Healthcare Workers in the Time of COVID-19. New Solut. 2021, 30, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, A.; Forchuk, C.A.; Houle, S.A.; Hansen, K.T.; Plouffe, R.A.; Liu, J.J.W.; Dempster, K.S.; Le, T.; Kocha, I.; Hosseiny, F.; et al. Exposure to Moral Stressors and Associated Outcomes in Healthcare Workers: Prevalence, Correlates, and Impact on Job Attrition. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2024, 15, 2306102. Available online: https://awspntest.apa.org/doi/10.1080/20008066.2024.2306102 (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Epstein, E.G.; Whitehead, P.B.; Prompahakul, C.; Thacker, L.R.; Hamric, A.B. Enhancing Understanding of Moral Distress: The Measure of Moral Distress for Health Care Professionals. AJOB Empir. Bioeth. 2019, 10, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsalem, D.; Lazarov, A.; Markowitz, J.C.; Naiman, A.; Smith, T.E.; Dixon, L.B.; Neria, Y. Psychiatric Symptoms and Moral Injury among US Healthcare Workers in the COVID-19 Era. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plouffe, R.A.; Nazarov, A.; Forchuk, C.A.; Gargala, D.; Deda, E.; Le, T.; Bourret-Gheysen, J.; Jackson, B.; Soares, V.; Hosseiny, F.; et al. Impacts of Morally Distressing Experiences on the Mental Health of Canadian Health Care Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1984667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamiani, G.; Borghi, L.; Argentero, P. When Healthcare Professionals Cannot Do the Right Thing: A Systematic Review of Moral Distress and Its Correlates. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 22, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burston, A.S.; Tuckett, A.G. Moral Distress in Nursing: Contributing Factors, Outcomes and Interventions. Nurs. Ethics 2012, 20, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, J. Moral Injury. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2014, 31, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litz, B.T.; Stein, N.; Delaney, E.; Lebowitz, L.; Nash, W.P.; Silva, C.; Maguen, S. Moral Injury and Moral Repair in War Veterans: A Preliminary Model and Intervention Strategy. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litz, B.T.; Plouffe, R.A.; Nazarov, A.; Murphy, D.; Phelps, A.; Coady, A.; Houle, S.A.; Dell, L.; Frankfurt, S.; Zerach, G.; et al. Defining and Assessing the Syndrome of Moral Injury: Initial Findings of the Moral Injury Outcome Scale Consortium. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 923928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterbrook, B.; Plouffe, R.A.; Houle, S.A.; Liu, A.; McKinnon, M.C.; Ashbaugh, A.R.; Mota, N.; Afifi, T.O.; Enns, M.W.; Richardson, J.D.; et al. Moral Injury Associated with Increased Odds of Past-Year Mental Health Disorders: A Canadian Armed Forces Examination. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2023, 14, 2192622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandro-Lowe, A.M.; Patel, H.; Easterbrook, B.; Ritchie, K.; Brown, A.; Xue, Y.; Karram, M.; Millman, H.; Sullo, E.; Pichtikova, M.; et al. The Independent and Combined Impact of Moral Injury and Moral Distress on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2024, 15, 2299661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Easterbrook, B.; D’Alessandro-Lowe, A.M.; Andrews, K.; Hosseiny, F.; Rodrigues, S.; Malain, A.; O’Connor, C.; Schielke, H.; McCabe, R.E.; et al. Associations between Trauma and Substance Use among Healthcare Workers and Public Safety Personnel during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: The Mediating Roles of Dissociation and Emotion Dysregulation. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2023, 14, 2180706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, S.E.; Chin, K.H.; Glick, D.R.; Wickwire, E.M. Trends in Moral Injury, Distress, and Resilience Factors among Healthcare Workers at the Beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguen, S.; Griffin, B.J.; Copeland, L.A.; Perkins, D.F.; Richardson, C.B.; Finley, E.P.; Vogt, D. Trajectories of Functioning in a Population-Based Sample of Veterans: Contributions of Moral Injury, PTSD, and Depression. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 2332–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguen, S.; Nichter, B.; Norman, S.B.; Pietrzak, R.H. Moral Injury and Substance Use Disorders among US Combat Veterans: Results from the 2019–2020 National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 1364–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, A.B.O.; Bryan, C.J.; Morrow, C.E.; Etienne, N.; Sannerud, B.R. Moral Injury, Suicidal Ideation, and Suicide Attempts in a Military Sample. Traumatology 2014, 20, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Belz, Y.; Dichter, N.; Zerach, G. Moral Injury and Suicide Ideation Among Israeli Combat Veterans: The Contribution of Self-Forgiveness and Perceived Social Support. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP1031–NP1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litz, B.T.; Kerig, P.K. Introduction to the Special Issue on Moral Injury: Conceptual Challenges, Methodological Issues, and Clinical Applications. J. Trauma. Stress 2019, 32, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, A.; Cahill, J.M.; Dugdale, L.S. Moral Injury in Health Care: Identification and Repair in the COVID-19 Era. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Hasan, O.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sinsky, C.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; West, C.P. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction with Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1600–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maunder, R.G.; Heeney, N.D.; Greenberg, R.A.; Jeffs, L.P.; Wiesenfeld, L.A.; Johnstone, J.; Hunter, J.J. The Relationship between Moral Distress, Burnout, and Considering Leaving a Hospital Job during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Survey. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklar, M.; Ehrhart, M.G.; Aarons, G.A. COVID-Related Work Changes, Burnout, and Turnover Intentions in Mental Health Providers: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2021, 44, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, K.N.; Runk, B.G.; Maduro, R.S.; Fancher, M.; Mayo, A.N.; Wilmoth, D.D.; Morgan, M.K.; Zimbro, K.S. Nursing Moral Distress and Intent to Leave Employment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2022, 37, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Ellatif, E.E.; Anwar, M.M.; AlJifri, A.A.; El Dalatony, M.M. Fear of COVID-19 and Its Impact on Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention Among Egyptian Physicians. Saf. Health Work 2021, 12, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J.; de los Santos, J.A.A. Fear of COVID-19, Psychological Distress, Work Satisfaction and Turnover Intention among Frontline Nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mansour, K. Stress and Turnover Intention among Healthcare Workers in Saudi Arabia during the Time of COVID-19: Can Social Support Play a Role? PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, P.; Kelifa, M.O.; Wang, B.; Liu, M.; Lu, L.; Wang, W. How Workplace Violence Correlates Turnover Intention among Chinese Health Care Workers in COVID-19 Context: The Mediating Role of Perceived Social Support and Mental Health. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Pei, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yan, W.; Gao, X.; Wang, W. Factors Associated with Turnover Intention among Healthcare Workers during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in China. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 4953–4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varasteh, S.; Esmaeili, M.; Mazaheri, M. Factors Affecting Iranian Nurses’ Intention to Leave or Stay in the Profession during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2022, 69, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimarolli, V.R.; Bryant, N.S.; Falzarano, F.; Stone, R. Factors Associated with Nursing Home Direct Care Professionals’ Turnover Intent during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Geriatr. Nurs. 2022, 48, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—A Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houle, S.A.; Ein, N.; Gervasio, J.; Plouffe, R.A.; Litz, B.T.; Carleton, R.N.; Hansen, K.T.; Liu, J.J.W.; Ashbaugh, A.R.; Callaghan, W.; et al. Measuring Moral Distress and Moral Injury: A Systematic Review and Content Analysis of Existing Scales. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 108, 102377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malach-Pines, A. The Burnout Measure, Short Version. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.T.; Keane, T.M.; Palmieri, P.A.; Marx, B.P.; Schnurr, P.P. PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Available online: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Lovibond, P.; Lovibond, S. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; Psychology Foundation: Sydney, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The Brief Resilience Scale: Assessing the Ability to Bounce Back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived Organizational Support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Personal. Assess. 2010, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Macintosh, Version 29; Available online: https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- VERBI Software. MAXQDA 2024; VERBI Software: Berlin, Germany, 2024; Available online: www.maxqda.com (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- D’Alessandro-Lowe, A.M.; Karram, M.; Ritchie, K.; Brown, A.; Millman, H.; Sullo, E.; Xue, Y.; Pichtikova, M.; Schielke, H.; Malain, A.; et al. Coping, Supports and Moral Injury: Spiritual Well-Being and Organizational Support Are Associated with Reduced Moral Injury in Canadian Healthcare Providers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The Measurement of Experienced Burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Ali, G.; Ahmed, I. Protecting Healthcare through Organizational Support to Reduce Turnover Intention. Int. J. Hum. Rights Healthc. 2018, 11, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.E.; Hanson, G.C.; Boyce, D.; Ley, C.D.; Swavely, D.; Reina, M.; Rushton, C.H. Organizational Impact on Healthcare Workers’ Moral Injury During COVID-19: A Mixed-Methods Analysis. J. Nurs. Adm. 2022, 52, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Malliarou, M.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Kaitelidou, D. Association between Organizational Support and Turnover Intention in Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahed, N.A.A.; Al Doghan, M.A.; Saraih, U.N.; Soomro, B.A. Forecasting Turnover Intention: An Analysis of Psychological Factors and Perceived Organizational Support among Healthcare Professionals. Int. J. Hum. Rights Healthc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Survey | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | N/A | Healthcare providers (HCPs) were asked to provide basic demographic (e.g., age, sex, gender, race, province of residence) and occupational (e.g., profession, years worked, occupational setting, employment status) information. |

| Turnover Intention | N/A | HCPs were asked to report their current likelihood of leaving both their organization and their profession, separately, on a 5-point scale ranging from 0% to 100% likely. The survey item read: “Given the current situation, please indicate the likelihood that you will leave your organization/employer”. The same wording was used for a second question with reference to leaving one’s profession. |

| Moral Distress | Measure of Moral Distress—Healthcare Professional (MMD-HP) [23] | The MMD-HP was used to assess exposure to morally stressful events, as per Houle et al.’s [55] recommendation on the most appropriate usage for this scale. Participants read 27 statements about morally distressing events in the healthcare context and were asked to rate each item twice, once for frequency of occurrence and once for degree of distress. Participants rated each item on a scale from “0—Never/None” to “4—Very Frequently/Very Distressing”. Total scores were calculated by summing the products of the frequency and distress scores. Internal consistency in the present sample was α = 0.95 for the frequency scale and α = 0.97 for the distress scale. |

| Moral Injury | Moral Injury Outcomes Scale (MIOS) [30] | The MIOS was used to assess for moral injury. The MIOS is a 14-item Likert-type scale in which participants are asked to rate their degree of agreement with items on a scale ranging from 0—Strongly Disagree to 4—Strongly Agree. The MIOS has a two-factor structure: shame-related moral injury (sum of items 1, 3, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14) and trust-violation-related outcomes (sum of items 2, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11). Internal consistency in the present sample was α = 0.86 for the shame subscale and 0.78 for the trust-violation subscale. |

| Burnout | Burnout Measure Short (BMS) [56] | The BMS was used to assess burnout. The BMS is a 10-item scale that asks participants to rate their level of agreement with various aspects of burnout (e.g., helpless, trapped, hopeless) on a scale ranging from 1—Never to 7—Always with respect to their work-related experiences. Total scores were calculated by summing participant responses across items. Internal consistency in the present sample was α = 0.92. |

| Post-traumatic Stress | Post-Traumatic Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) [57] | The PCL-5 was used to assess post-traumatic stress. Participants read 20 statements and rated their agreement with each statement on a scale from 0 to 4. Total scores were calculated by summing participant responses across the 20 items. A score between 31 and 33 has been considered as indicative of potential PTSD. Internal consistency in the present sample was α = 0.96. |

| Depression | Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) [58] | The depression subscale of the DASS-21 was used to assess symptoms of depression. The DASS-21 includes 21 items and asks participants to read and rate their degree of agreement with each item on a scale ranging from 0—Never to 3—Almost Always based on the item’s relevance over the past week. Interpretation of depression scores is as follows: 0–9 Normal, 10–13 Mild, 14–20 Moderate, 21–27 Severe, 28+ Extremely Severe. The internal consistency of the depression subscale in the present sample was α = 0.91. |

| Anxiety | Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) [58] | The anxiety subscale of the DASS-21 was used to assess symptoms of depression. The DASS-21 includes 21 items and asks participants to read and rate their degree of agreement with each item on a scale ranging from 0—Never to 3—Almost Always based on the item’s relevance over the past week. Interpretation of anxiety scores is as follows: 0–7 Normal, 8–9 Mild, 10–14 Moderate, 15–19 Severe, 20+ Extremely Severe. The internal consistency of the anxiety subscale in the present sample was α = 0.84. |

| Resilience | Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) [59] | The BRS was used to assess resilience, or one’s ability to “bounce back” in the face of stress. Participants read 6 items and rated their degree of agreement with each statement on a scale from 1—Strongly Disagree to 5—Strongly Agree. Total scores were calculated by summing participant responses. The internal consistency in the present sample was α = 0.88. |

| Organizational Support | Survey of Perceived Organizational Support (SPOS) [60] | The 16-item version of the SPOS was used to assess the degree to which HCPs believed their “organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being” [60] (p. 1). Participants were asked to rate their degree of agreement with 16 statements on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Total scores were calculated by taking the average of participant responses. The internal consistency in the present sample was α = 0.93. |

| Social Support | Multidimensional Measure of Social Support (MSPSS) [61] | The MSPSS was used to assess social support across the domains of family, friends, and significant others. The MSPSS is a 12-item scale where participants are asked to rate their degree of agreement with statements regarding social support on a Likert-type scale ranging from very strongly disagree to very strongly agree. Total scores were calculated by taking the average score across items. The internal consistency in the present sample was α = 0.94. |

| Variable | Level | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 33 | 8.3 | |

| Female | 364 | 91.5 | |

| Missing | <5 | - | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 31 | 7.8 | |

| Female | 360 | 90.5 | |

| Gender Diverse | 5 | 1.3 | |

| Missing | <5 | - | |

| Ethnicity * | |||

| African | 5 | 1.3 | |

| Caribbean | 6 | 1.5 | |

| East Asian | 9 | 2.3 | |

| First Nations, Inuit, or Metis | 20 | 5.0 | |

| Latin American | 5 | 1.3 | |

| Middle Eastern | 5 | 1.3 | |

| South Asian | 11 | 2.8 | |

| Southeast Asian | <5 | - | |

| European | 244 | 61.3 | |

| Other | 75 | 18.8 | |

| Missing | 22 | 5.5 | |

| Province | |||

| British Columbia | 38 | 9.5 | |

| Alberta | 32 | 8.0 | |

| Saskatchewan | 7 | 1.8 | |

| Manitoba | 23 | 5.8 | |

| Ontario | 248 | 62.3 | |

| Quebec | 6 | 1.5 | |

| New Brunswick | 21 | 5.3 | |

| Nova Scotia | 14 | 3.5 | |

| Prince Edward Island | <5 | - | |

| Newfoundland/Labrador | <5 | - | |

| Northwest Territories | <5 | - | |

| Yukon | <5 | - | |

| Missing | <5 | - | |

| Profession | |||

| Registered (Practical) Nurse | 225 | 56.5 | |

| Medical Physician | 14 | 3.5 | |

| Respiratory Therapist | 6 | 1.5 | |

| Personal Support Worker | 25 | 6.3 | |

| Occupational Therapist | 11 | 2.8 | |

| Physiotherapist | 5 | 1.3 | |

| Social Worker | 32 | 8.0 | |

| Recreational Therapist | 10 | 2.5 | |

| Other | 70 | 17.6 | |

| Missing | <5 | - | |

| Occupational Setting | |||

| Acute Care Hospital | 166 | 41.7 | |

| Primary Care | 21 | 5.3 | |

| Mental Health Hospital | 12 | 3.0 | |

| Rehabilitation Hospital | <5 | - | |

| Long-term Care or Retirement | 99 | 24.9 | |

| Community or Home Care | 31 | 7.8 | |

| Public Health | 22 | 5.5 | |

| Other | 45 | 11.3 | |

| Missing | <5 | - | |

| Employment Status | |||

| Full-time | 285 | 71.6 | |

| Part-time | 84 | 21.1 | |

| Casual | 15 | 3.8 | |

| Student | <5 | - | |

| Other | 10 | 2.5 | |

| Missing | <5 | - | |

| Turnover Intention—Organization | |||

| 0% Likely | 83 | 20.9 | |

| 25% Likely | 102 | 25.6 | |

| 50% Likely | 98 | 24.6 | |

| 75% Likely | 55 | 13.8 | |

| 100% Likely | 58 | 14.6 | |

| Missing | <5 | - | |

| Turnover Intention—Profession | |||

| 0% Likely | 125 | 31.4 | |

| 25% Likely | 112 | 28.1 | |

| 50% Likely | 90 | 22.6 | |

| 75% Likely | 34 | 8.5 | |

| 100% Likely | 33 | 8.3 | |

| Missing | <5 | - |

| Construct | Scale | N | Median | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moral Distress | MMD-HP | 218 | 130.50 | 137.87 | 97.18 |

| Moral Injury—Shame | MIOS | 314 | 8.00 | 8.59 | 5.96 |

| Moral Injury—Trust | MIOS | 315 | 13.00 | 12.58 | 5.55 |

| Burnout | BMS | 297 | 44.00 | 43.68 | 12.78 |

| Post-traumatic Stress | PCL-5 | 291 | 27.00 | 28.58 | 18.94 |

| Depression | DASS-21 | 279 | 12.00 | 13.48 | 9.83 |

| Anxiety | DASS-21 | 279 | 8.00 | 9.41 | 8.05 |

| Resilience | BRS | 265 | 3.00 | 3.14 | 0.85 |

| Social Support | MSPSS | 281 | 5.42 | 5.23 | 1.27 |

| Organizational Support | SPOS | 379 | 3.31 | 3.54 | 1.43 |

| OR 95%CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE(B) | Exp(B) | Lower | Upper | |

| Sex | −0.15 | 0.3232 | 0.861 | 0.457 | 1.623 |

| Age | 0.006 | 0.0077 | 1.006 | 0.990 | 1.021 |

| Sex×Age | |||||

| Male | 0.001 | 0.01 | 1.001 | 0.981 | 1.234 |

| Female | 0.006 | 0.0078 | 1.006 | 0.991 | 1.021 |

| Years Worked | 0.021 | 0.0081 | 1.021 * | 1.005 | 1.038 |

| Moral Distress | 0.006 | 0.0013 | 1.006 ** | 1.004 | 1.009 |

| Moral Injury—SR | 0.061 | 0.0168 | 1.063 ** | 1.029 | 1.099 |

| Moral Injury—TVR | 0.107 | 0.0187 | 1.113 ** | 1.074 | 1.155 |

| Burnout | 0.087 | 0.0083 | 1.091 ** | 1.074 | 1.110 |

| Post−Traumatic Stress | 0.022 | 0.0058 | 1.022 ** | 1.010 | 1.034 |

| Depression | 0.038 | 0.0115 | 1.039 ** | 1.015 | 1.062 |

| Anxiety | 0.042 | 0.0134 | 1.043 ** | 1.015 | 1.070 |

| Resilience | −0.093 | 0.1292 | 0.911 | 0.707 | 1.176 |

| Social Support | −0.135 | 0.0897 | 0.874 | 0.732 | 1.044 |

| Organizational Support | −0.731 | 0.075 | 0.481 ** | 0.416 | 0.558 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | OR (95% CI) | B (SE) | OR (95% CI) | B (SE) | OR (95% CI) | B (SE) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Years Worked | 0.021 (0.008) | 1.021 (1.005, 1.038) * | 0.024 (0.008) | 1.024 (1.007, 1.041) ** | 0.019 (0.009) | 1.019 (1.002, 1.037) * | 0.018 (0.009) | 1.018 (1.001, 1.036) * |

| Moral Distress | 0.004 (0.001) | 1.004 (1.001, 1.007) ** | 0.002 (0.001) | 1.002 (0.999, 1.005) | 0.00 (0.002) | 1.00 (0.997, 1.003) | ||

| Moral Injury—SR | 0.019 (0.019) | 1.019 (0.982, 1.059) | 0.009 (0.021) | 1.009 (0.969, 1.050) | 0.005 (0.021) | 1.005 (0.964, 1.047) | ||

| Moral Injury—TVR | 0.081 (0.022) | 1.084 (1.039, 1.132) ** | 0.016 (0.025) | 1.016 (0.968, 1.067) | 0.006 (0.026) | 1.006 (0.956, 1.058) | ||

| Burnout | 0.088 (0.011) | 1.092 (1.069, 1.115) ** | 0.066 (0.011) | 1.068 (1.045, 1.093) ** | ||||

| Post-traumatic Stress | −0.011 (0.009) | 0.989 (0.970, 1.008) | −0.006 (0.010) | 0.994 (0.975, 1.013) | ||||

| Depression | −0.009 (0.017) | 0.991 (0.959, 1.025) | −0.006 (0.017) | 0.994 (0.962, 1.027) | ||||

| Anxiety | 0.004 (0.020) | 1.004 (0.967, 1.044) | 0.006 (0.021) | 1.006 (0.966, 1.049) | ||||

| Organizational Support | −0.431 (0.092) | 0.650 (0.542, 0.779) ** | ||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 = 0.017 | Nagelkerke R2 = 0.239 | Nagelkerke R2 = 0.279 | Nagelkerke R2 = 0.348 | |||||

| OR 95%CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE(B) | Exp(B) | Lower | Upper | |

| Years Worked | 0.018 | 0.009 | 1.018 * | 1.001 | 1.036 |

| Burnout | 0.059 | 0.010 | 1.061 ** | 1.041 | 1.081 |

| Organizational Support | −0.467 | 0.085 | 0.627 ** | 0.530 | 0.741 |

| OR 95%CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE(B) | Exp(B) | Lower | Upper | |

| Sex | −0.362 | 0.3305 | 0.696 | 0.365 | 1.331 |

| Age | 0.018 | 0.0079 | 1.018 * | 1.002 | 1.034 |

| Sex×Age | |||||

| Male | 0.008 | 0.0102 | 1.008 | 0.988 | 1.028 |

| Female | 0.019 | 0.0079 | 1.019 * | 1.004 | 1.036 |

| Years Worked | 0.027 | 0.0082 | 1.027 ** | 1.011 | 1.044 |

| Moral Distress | 0.007 | 0.0013 | 1.007 ** | 1.004 | 1.010 |

| Moral Injury—SR | 0.053 | 0.0168 | 1.054 ** | 1.020 | 1.090 |

| Moral Injury—TVR | 0.105 | 0.0193 | 1.111 ** | 1.069 | 1.154 |

| Burnout | 0.082 | 0.0084 | 1.085 ** | 1.068 | 1.104 |

| Post-traumatic Stress | 0.022 | 0.0058 | 1.022 ** | 1.010 | 1.034 |

| Depression | 0.04 | 0.0119 | 1.041 ** | 1.016 | 1.066 |

| Anxiety | 0.042 | 0.0136 | 1.043 ** | 1.016 | 1.071 |

| Resilience | −0.134 | 0.1353 | 0.875 | 0.669 | 1.142 |

| Social Support | −0.152 | 0.0894 | 0.859 | 0.720 | 1.271 |

| Organizational Support | −0.612 | 0.0751 | 0.542 ** | 0.468 | 0.628 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | OR (95% CI) | B (SE) | OR (95% CI) | B (SE) | OR (95% CI) | B (SE) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Sex×Age | ||||||||

| Male | 0.008 (0.010) | 1.008 (0.988, 1.028) | 0.012 (0.011) | 1.012 (0.991, 1.034) | 0.019 (0.011) | 1.019 (0.998, 1.041) | 0.019 (0.011) | 1.019 (0.998, 1.041) |

| Female | 0.019 (0.008) | 1.019 (1.004, 1.036) * | 0.024 (0.008) | 1.024 (1.008, 1.041) ** | 0.028 (0.009) | 1.028 (1.011, 1.046) ** | 0.029 (0.009) | 1.029 (1.012, 1.046) ** |

| Moral Distress | 0.005 (0.0014) | 1.005 (1.002, 1.008) ** | 0.003 (0.002) | 1.003 (1.000, 1.006) | 0.001 (0.002) | 1.011 (0.998, 1.004) | ||

| Moral Injury—SR | 0.006 (0.020) | 1.006 (0.967, 1.047) | −0.010 (0.023) | 0.990 (0.946, 1.037) | −0.01 (0.023) | 0.990 (0.946, 1.036) | ||

| Moral Injury—TVR | 0.082 (0.024) | 1.085 (1.035, 1.139) ** | 0.024 (0.026) | 1.024 (0.973, 1.079) | 0.017 (0.026) | 1.017 (0.967, 1.071) | ||

| Burnout | 0.082 (0.011) | 1.085 (1.063, 1.108) ** | 0.066 (0.012) | 1.068 (1.044, 1.093) ** | ||||

| Post-traumatic Stress | −0.008 (0.011) | 0.992 (0.971, 1.014) | −0.005 (0.010) | 0.995 (0.975, 1.016) | ||||

| Depression | −0.002 (0.0205) | 0.998 (0.957, 1.040) | −0.002 (0.020) | 0.998 (0.959, 1.039) | ||||

| Anxiety | 0.009 (0.020) | 1.009 (0.969, 1.049) | 0.01 (0.020) | 1.01 (0.971, 1.051) | ||||

| Organizational Support | −0.311 (0.095) | 0.733 (0.609, 0.882) ** | ||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 = 0.019 | Nagelkerke R2 = 0.267 | Nagelkerke R2 = 0.345 | Nagelkerke R2 = 0.361 | |||||

| OR 95%CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE(B) | Exp(B) | Lower | Upper | |

| Sex×Age | 0.018 | 0.011 | 1.018 | 0.997 | 1.040 |

| Male | 0.028 | 0.008 | 1.028 | 1.012 | 1.045 |

| Female | 0.067 | 0.010 | 1.069 ** | 1.049 | 1.090 |

| Burnout | −0.341 | 0.088 | 0.711 ** | 0.599 | 0.845 |

| Organizational Support | 0.018 | 0.011 | 1.018 ** | 0.997 | 1.040 |

| Quantitative | Qualitative | Mixed-Methods Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Turnover Intention | ||

Organization

Profession

| There were no distinct patterns of meaning identified between qualitative responses pertaining to organizational turnover vs. professional turnover. Furthermore, patterns of meaning drawn from the data were not distinguishable across the levels of turnover likelihood. As such, the qualitative data were analyzed as a whole rather than based on subgroups. HCPs who described contentment to stay in their organization or professional highlighted the value of supportive leadership and noted the pride and passion they hold for their work. HCPs described a process of wrestling with the costs and benefits of remaining in their occupation and/or profession. Some HCPs expressed that the toll of the working circumstances outweighed any benefit of remaining in their occupation or profession. Others had a stronger desire to leave yet felt constrained from leaving due to practical or personal reasons. Finally, some HCPs described being on the lookout for a better employment option, such that they were ready to make the move if something else came up. | Convergence and Expansion Both the quantitative and qualitative results speak to the idea that most HCPs surveyed were somewhere on a continuum of intending to leave their organization and/or profession. The qualitative data expand upon the quantified turnover likelihood ratings by suggesting that HCPs’ ratings may differ as HCPs may find themselves at different places of weighing the costs and benefits of leaving their organization/employer. The qualitative findings further expand the quantitative results by suggesting that a HCP who rated a turnover likelihood of 50%, for example, is not necessarily uninterested in leaving but rather may be at a different place of wrestling costs and benefits than someone who rated their turnover intention at 75% or 100%. |

| Influences on Turnover Intention | ||

| Organization Years worked, moral distress, and trust-violation-related moral injury were each significantly associated with increased odds of turnover intention in the second iteration of the model. The effects of moral distress and trust-violation-related moral injury were, however, washed out by the addition of burnout in the third iteration of the model. The final model indicated that whereas years worked and burnout were associated with increased odds of turnover intention, perceived organizational support was associated with decreased odds of turnover intention. Profession The same pattern of results was found for intention to leave a profession, save for the importance of age-by-sex interaction in place of years worked. | While the qualitative data did not explicitly set out to identify “factors” associated with turnover intention, the themes “Drowning and No One Cares” and “Moral Stressors” provide insight into influences on HCPs’ experiences and perspectives of turnover intention. Drowning and No One Cares HCPs described working in challenging conditions that introduced significant strain on mental health and well-being. These experiences were further complicated by a perceived lack of acknowledgment and support from leadership. Moral Stressors Amid such working conditions, HCPs described a transgression of their value to provide adequate patient care and to be cared for by leaders. Furthermore, many HCPs noted “retirement” in their comments qualifying their turnover likelihood ratings. | Convergence and Expansion The qualitative data provide context to the quantitative findings. The quantitative results demonstrate that HCPs who are more likely to leave are those who perceive low organizational support, those who report high levels of burnout, and those who report an older age. The qualitative findings expand upon these results by painting the picture of challenging working conditions that created situations that violated HCPs’ values and resulted in a perception that leadership did not care about them. Moreover, the qualitative results expand upon the quantitative finding that age is associated with increased turnover likelihood by pointing out that many individuals noted retirement as a reason for qualifying their turnover ratings. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Alessandro-Lowe, A.M.; Brown, A.; Sullo, E.; Pichtikova, M.; Karram, M.; Mirabelli, J.; McCabe, R.E.; McKinnon, M.C.; Ritchie, K. Why Are Healthcare Providers Leaving Their Jobs? A Convergent Mixed-Methods Investigation of Turnover Intention among Canadian Healthcare Providers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2030-2060. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030152

D’Alessandro-Lowe AM, Brown A, Sullo E, Pichtikova M, Karram M, Mirabelli J, McCabe RE, McKinnon MC, Ritchie K. Why Are Healthcare Providers Leaving Their Jobs? A Convergent Mixed-Methods Investigation of Turnover Intention among Canadian Healthcare Providers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(3):2030-2060. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030152

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Alessandro-Lowe, Andrea M., Andrea Brown, Emily Sullo, Mina Pichtikova, Mauda Karram, James Mirabelli, Randi E. McCabe, Margaret C. McKinnon, and Kim Ritchie. 2024. "Why Are Healthcare Providers Leaving Their Jobs? A Convergent Mixed-Methods Investigation of Turnover Intention among Canadian Healthcare Providers during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Nursing Reports 14, no. 3: 2030-2060. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030152

APA StyleD’Alessandro-Lowe, A. M., Brown, A., Sullo, E., Pichtikova, M., Karram, M., Mirabelli, J., McCabe, R. E., McKinnon, M. C., & Ritchie, K. (2024). Why Are Healthcare Providers Leaving Their Jobs? A Convergent Mixed-Methods Investigation of Turnover Intention among Canadian Healthcare Providers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nursing Reports, 14(3), 2030-2060. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030152