Mapping and Characterizing Instruments for Assessing Family Nurses’ Workload: Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Identification

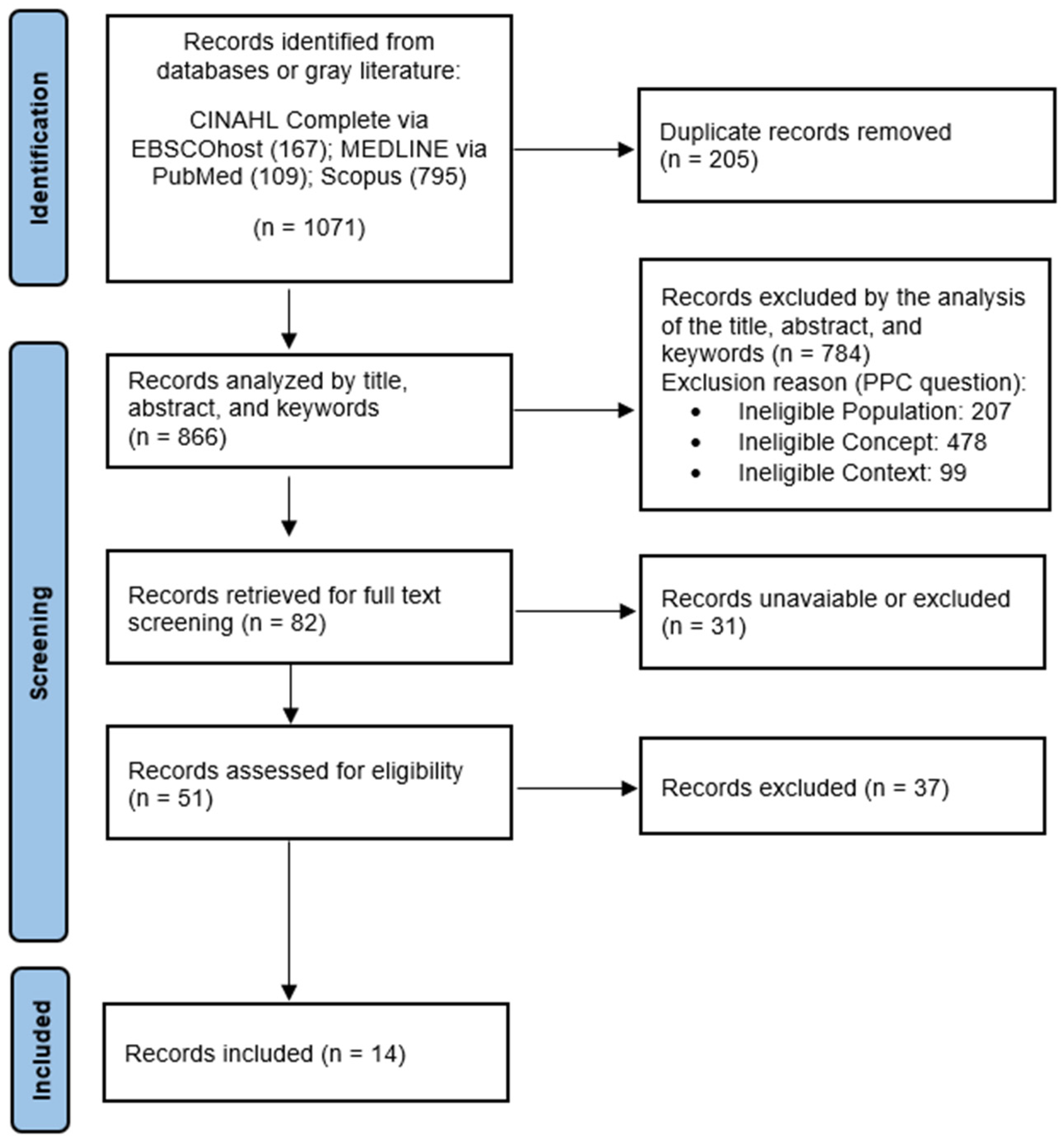

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pérez-Francisco, D.H.; Duarte-Clíments, G.; Del Rosario-Melián, J.M.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Romero-Martín, M.; Sánchez-Gómez, M.B. Influence of Workload on Primary Care Nurses’ Health and Burnout, Patients’ Safety, and Quality of Care: Integrative Review. Healthcare 2020, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, P.; Tham, T.L.; Sheehan, C.; Cooper, B. The impact of perceived workload on nurse satisfaction with work-life balance and intention to leave the occupation. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2019, 49, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegney, D.G.; Rees, C.S.; Osseiran-Moisson, R.; Breen, L.; Eley, R.; Windsor, C.; Harvey, C. Perceptions of nursing workloads and contributing factors, and their impact on implicit care rationing: A Queensland, Australia study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, P.; Saville, C.; Ball, J.; Jones, J.; Pattison, N.; Monks, T.; Safer Nursing Care Study Group. Nursing workload, nurse staffing methodologies and tools: A systematic scoping review and discussion. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 103, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghamdi, M.G. Nursing workload: A concept analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, R.; MacNeela, P.; Scott, A.; Treacy, P.; Hyde, A. Reconsidering the conceptualization of nursing workload: Literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 57, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.; Rogers, C.; King, C. Safety culture and an invisible nursing workload. Collegian 2019, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellafiore, F.; Caruso, R.; Cossu, M.; Russo, S.; Baroni, I.; Barello, S.; Vangone, I.; Acampora, M.; Conte, G.; Magon, A.; et al. The State of the Evidence about the Family and Community Nurse: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, L.; Leggat, S.G.; Cheng, C.; Donohue, L.; Bartram, T.; Oakman, J. Are organisational factors affecting the emotional withdrawal of community nurses? Aust. Health Rev. 2017, 41, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, F.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liang, Y. Work characteristics and psychological symptoms among GPs and community nurses: A preliminary investigation in China. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2016, 28, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyürek, P.; Kiliç, I. The Psychometric Properties of the Turkish Version of Individual Workload Perception Scale for Medical and Surgical Nurses. J. Nurs. Meas. 2022, 30, 778–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbab, M.S.; Martín, G.I.; Vilamala, I.R.; Llorente, S.; Díaz, C.R.; Calero, M.F. Análisis de las cargas de trabajo de las enfermeras en la UCI gracias a la escala NAS. Enferm. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Havaei, F.; MacPhee, M. The impact of heavy nurse workload and patient/family complaints on workplace violence: An application of human factors framework. Nurs. Open 2020, 7, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biff, D.; Pires, D.E.P.; Forte, E.C.N.; Trindade, L.L.; Machado, R.R.; Amadigi, F.R.; Scherer, M.D.D.A.; Soratto, J. Nurses’ workload: Lights and shadows in the Family Health Strategy: Cargas de trabalho de enfermeiros: Luzes e sombras na Estratégia Saúde da Família. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2020, 25, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Scoping reviews (2024). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI: Miami, FL, USA, 2020; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 13 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alenezi, A.M.; Aboshaiqah, A.; Baker, O. Work-related stress among nursing staff working in government hospitals and primary health care centres. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2018, 24, e12676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, P.O.; Ramos, F.R.S.; Barlem, E.L.D.; Dalmolin, G.L.; Schneider, D.G. Validation of a moral distress instrument in nurses of primary health care. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2018, 26, e3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, C.L.; Engelbrecht, M.C. Job satisfaction and dissatisfaction of professional nurses in Primary Health Care facilities in the Free State Province of South Africa. Afr. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2009, 11, 104–117. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10500/9822 (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Cortés Rubio, J.A.; Martín Fernández, J.; Morente Páez, M.; Caboblanco Muñoz, M.; Garijo Cobo, J.; Rodríguez Balo, A. Clima laboral en atención primaria: Qué hay que mejorar? Working atmosphere in primary care: What needs improving? Aten. Primaria 2003, 32, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Engelbrecht, M.C.; Bester, C.L.; Van Den Berg, H.; Van Rensburg, H.C.J. A study of predictors and levels of burnout: The case of professional nurses in primary health care facilities in the free state. S. Afr. J. Econ. 2008, 76 (Suppl. S1), S15–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdikien, N.; Asikainen, P.; Balčiūnas, S.; Suominen, T. Do nurses feel stressed? A perspective from primary health care. Nurs. Health Sci. 2014, 16, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.; Wang, H.H. Perceived occupational stress and related factors in public health nurses. J. Nurs. Res. 2002, 10, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Fernandez, J.; Gomez-Gascon, T.; Beamud-Lagos, M.; Cortes-Rubio, J.A.; Alberquilla-Menendez-Asenjo, A. Professional quality of life and organizational changes: A five-year observational study in Primary Care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2007, 7, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, A.C.; Madroño, M.Á.C. Work-related satisfaction of nursing professionals in Talavera de la Reina. Metas Enferm. 2012, 15, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Purohit, B.L.S.; Banopadhyay, T. Job Satisfaction among Public Sector Doctors and Nurses in India. J. Health Manag. 2021, 23, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, S.; Adam, S. Job Satisfaction among Nurses Working at Primary Health Center in Ras Al Khaimah, United States Emirates. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. 2020, 12, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Guo, H.; Liu, S.; Li, J. Work stress and job satisfaction of community health nurses in Southwest China. Biomed. Res. 2018, 29, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.V.; García, T.; Zuzuárregui, M.S.G.; Sánchez, S.S.; Conejo, R.O. Professional quality of life in workers of the Toledo primary care health area. Rev. Calid. Asist. 2015, 30, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfim, D.; Pereira, M.J.; Pierantoni, C.R.; Haddad, A.E.; Gaidzinski, R.R. Tool to measure workload of health professionals in Primary Health Care: Development and validation. Instrumento de medida de carga de trabalho dos profissionais de Saúde na Atenção Primária: Desenvolvimento e validação. Rev. Es. Enferm. USP 2015, 49, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.; Seabra, P. Assessment of nursing workload in adult psychiatric inpatient units: A scoping review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 25, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiecień, K.; Wujtewicz, M.; Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W. Selected methods of measuring workload among intensive care nursing staff. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2012, 25, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério da Saúde. Despacho No. 10321/2012 de 1 de Agosto: Diário da República No. 148/2012—II Série; Ministério da Saúde: Lisboa, Portugal, 2012.

- Ministério da Saúde. Regulamento No. 126/2011, de 18 de Fevereiro, Publicado Pela Ordem dos Enfermeiros em Diário da República, 2ª série, No. 35; Ministério da Saúde: Lisboa, Portugal, 2011.

- Ministério da Saúde. Decreto-Lei No. 298/2007 de 22 de Agosto: Diário da República No. 161/2007—I Série A; Ministério da Saúde: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007.

- Souza, P.; Cucolo, D.F.; Perroca, M.G. Nursing workload: Influence of indirect care interventions. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2019, 53, e03440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, L.; Wickens, C.D.; Hancock, G.; Hancock, P.A. Human Mental Workload: A Survey and a Novel Inclusive Definition. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 883321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, K.; De Veer, A.J.E.; Munster, A.M.; Francke, A.L.; Paans, W. Nursing documentation and its relationship with perceived nursing workload: A mixed-methods study among community nurses. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babapour, A.R.; Gahassab-Mozaffari, N.; Fathnezhad-Kazemi, A. Nurses’ job stress and its impact on quality of life and caring behaviors: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejours, C.; Abdoucheli, E.; Jayet, C. Psicodinâmica do Trabalho. In Psicologia e Saúde em Debate, 1st ed.; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2014; Volume 4, pp. 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Example of Search String | Hits |

|---|---|

| (((“workload”[Title/Abstract])AND(“assessment”[Title/Abstract]OR“evaluation”[Title/Abstract]OR“instrument”[Title/Abstract]OR “scale”[Title/Abstract]OR“measurement”[Title/Abstract]))AND(“nursing”[Title/Abstract]OR“nurse”[Title/Abstract]OR“nurses”[Title/Abstract]))AND(“primary care”[Title/Abstract]OR“primary health care”[Title/Abstract]) | 109 |

| Title (Authors/Year) | Instrument | Dimensions (Number of Items) | Workload Sub-Scale (Number of Items) | Internal Consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Sub-Scale | ||||

| Alenezi et al. (2018) [17]—Saudi Arabia | Nursing stress scale | 7 (34 items) | Workload (6 items) | 0.94 | -- |

| Barth et al. (2018) [18]—Brazil | Moral stress scale | 6 (46 items) | Overload (5 items) | 0.98 | 0.88 |

| Bester & Engelbrecht (2009) [19]—South Africa | Multidimensional instrument built by the researchers | no dimensions identified (5 items) | Quantitative Workload Inventory (5 items) | -- | 0.85 |

| Cortés-Rubio et al. (2003) [20]—Spain | PQL-35 (Spanish version) | 3 (35 items) | Workload (12 items) | -- | 0.75–0.86 |

| Engelbrecht et al. (2008) [21]—South Africa | Multidimensional instrument built by the researchers | no dimensions identified (5 items) | Quantitative Workload Inventory (5 items) | -- | 0.85 |

| Galdikien et al. (2014) [22]—Lithuania | Expanded nursing stress scale | 9 (55 items) | Workload (8 items) | 0.92 | 0.85 |

| Lee & Wang (2002) [23]—Taiwan | Stressors scale | 6 (40 items) | Workload (6 items) | 0.96 | 0.83 |

| Martin-Fernandez et al. (2007) [24]—Spain | PQL-35 (Spanish version) | 3 (35 items) | Workload (12 items) | -- | 0.75–0.86 |

| Panadero & Madroño (2012) [25]—Spain | Font-roja questionnaire | 9 (26 items) | Work Pressure (3 items) | -- | 0.79 |

| Pérez-Francisco et al. (2020) [1]—Spain | Work conditions assessment scale | 3 (31 items) | Work Conditions (11 items) | -- | -- |

| Purohit & Banopadhyay (2021) [26]—India | Measure of job satisfaction | 7 (40 items) | Satisfaction with Workload (9 items) | 0.95 | 0.85 |

| Suleiman & Adam (2020) [27]—United Arab Emirates | Measure of job satisfaction | 7 (40 items) | Satisfaction with Workload (9 items) | 0.95 | 0.85 |

| Tao et al. (2018) [28]—China | Work stress scale (WSS) Job satisfaction scale (JSS) | WSS: 5 (40 items) JSS: 8 (35 items) | Workload (WSS: 5 items) (JSS: 5 items) | WSS—0.98; JSS—0.86 | -- |

| Castro et al. (2015) [29]—Spain | PQL-35 (Spanish version) | 3 (35 items) | Workload (12 items) | 0.80–0.85 | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dias, A.; Araújo, B.; Jesus, É. Mapping and Characterizing Instruments for Assessing Family Nurses’ Workload: Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2020-2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030151

Dias A, Araújo B, Jesus É. Mapping and Characterizing Instruments for Assessing Family Nurses’ Workload: Scoping Review. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(3):2020-2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030151

Chicago/Turabian StyleDias, António, Beatriz Araújo, and Élvio Jesus. 2024. "Mapping and Characterizing Instruments for Assessing Family Nurses’ Workload: Scoping Review" Nursing Reports 14, no. 3: 2020-2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030151

APA StyleDias, A., Araújo, B., & Jesus, É. (2024). Mapping and Characterizing Instruments for Assessing Family Nurses’ Workload: Scoping Review. Nursing Reports, 14(3), 2020-2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030151