Abstract

The integration of arts-based methods into nursing education is a topic of growing interest in nursing practice. While there is an emerging body of research on this subject, evidence on competence development remains vague, largely due to methodological weaknesses. The purpose of this review is to evaluate the effectiveness of arts-based pedagogy in nursing, specifically in terms of students’ changes in knowledge, skills, and attitudes. It explores which arts-based approaches to nursing education qualify as evidence-based practice in terms of nursing competence. A systematic critical review of research on arts-based pedagogy in nursing was conducted, identifying 43 relevant studies. These studies were assessed for methodological quality based on the CEC Standards for evidence-based practice, and 13 high-quality comparative studies representing a variety of arts-based approaches were selected. Creative drama was identified as the only evidence-based practice in the field, positively affecting empathy. The findings highlight a research gap in nursing education and emphasize the need for measurement and appraisal tools suitable for the peculiarities of arts-based pedagogy.

1. Introduction

Nursing has been described as both an art and a science since Florence Nightingale’s influential work, ‘The Art of Nursing’, was published in 1859 [1]. The artistic aspect of nursing has been a topic of discussion in the field of education for many years [2,3,4,5,6]. Scholars have complemented this concept by integrating liberal arts into nursing education [7,8,9,10]. This concept has been supported by professional associations [11] and global policy recommendations [12].

The inclusion of arts and humanities in the training of healthcare professionals aims to enhance learners’ competencies in clinical and personal skills [12]. In nursing education, the arts and humanities help learners comprehend and appreciate human experiences. Some argue that knowledge of aesthetics can improve nurses’ imaginative abilities and provide a more holistic understanding of themselves, human nature, and the caregiving process [13,14,15,16].

The integration of arts-based methods into nursing education has gained interest due to the growing recognition of the importance of a holistic approach to nursing [17,18]. This development aligns with the demand for competency-based education within curricula [12,19] and learner-centered approaches in the classroom, such as experiential learning [20].

In the sense of teaching through the arts, arts-based methods are a subfield of aesthetic teaching or aesthetic learning alongside teaching about and in the arts [15,21,22]. However, there is no appropriate term for using the arts as a didactic element. Common terms used in the literature include “arts-based learning” [23], “arts-based teaching” [24], “arts-based education” [25], and “arts-based pedagogy” [26,27]. These hyphenated terms highlight the interdisciplinary nature of arts-based teaching and learning, while also distinguishing it from artistic education and art pedagogy [28].

Arts-based pedagogy is a creative strategy that uses an art form to facilitate learning about another subject matter ([23], p. 53). This approach goes beyond decorative or entertaining elements in the classroom, such as background music (e.g., [29]). Learners engage with artistic works, perform them, or create their own. In this process, engagement with at least one art form, such as visual and performing arts, music, or literature, can aid in the acquisition of knowledge or skills in non-art subject areas [21,23,26]. Arts-based pedagogy facilitates experiential learning by considering sensory experience and aesthetic reflection as independent sources of knowledge and cognition [15,21].

Integrating arts and creative approaches into nursing education encourages students to explore beyond the traditional scientific and technical aspects of nursing and to engage with the emotional, social, and cultural aspects of the nursing profession. Arts-based approaches can increase learners’ involvement, motivation, and attention by drawing from their experiences and creating an emotional connection to difficult topics [26,27,30,31]. This pedagogy complements training that primarily focuses on cognitive and psychomotor learning goals by addressing the affective level of learning [23,26,32].

Nursing practice requires a complex set of competencies, including clinical skills, interpersonal abilities, and humanistic practice [33]. Arts-based pedagogy has been used to address many of these competencies. Researchers suggest that arts-based nursing education can assist future nurses in developing a professional identity. The arts are believed to enhance critical thinking, diagnostic skills, and communication abilities. Enhancing empathy toward clients contributes to improved patient care quality and patient-centered nursing [30,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Additionally, arts-based approaches have been recognized to strengthen nursing students’ resilience and help them cope with the high stress levels associated with the nursing profession [40,41].

Conceptual papers and empirical research generally present a positive view of arts-based nursing education and its effects, as reflected in relevant reviews. They either cover the entire field [27,32,42,43,44] or explore the integration of different genres within nursing education, such as the visual arts [31,45,46], drama [47,48], poetry [49,50,51], storytelling [52], and film (cinenurducation) [53,54].

However, many studies exploring the impact of art-based pedagogy in nursing education lack methodological quality and rigor. Most studies are qualitative and do not define what makes an intervention successful. It is suggested that qualitative studies may overestimate learning effects, while the actual development of competence may be lower than what a positive evaluation of arts-based learning experiences suggests [55]. In the case of quantitative research on arts-based pedagogy in nursing education, uncontrolled studies with limited internal validity are prevalent [56]. Outcome measures in many cases are not robust because they rely on participants’ self-assessment [43,57].

A rigorous evaluation of arts-based nursing education is necessary to determine its impact on learners’ knowledge acquisition, skill development, and attitudinal changes. Previous reviews have not systematically addressed this issue. Quantitative intervention studies are crucial in educational impact research because they allow for statistical verification of the causality between intervention and effect. They are an essential element of evidence-based practice (EBP), where the effectiveness of an intervention is the determining factor [58]. A practice is considered evidence-based if it is “supported by a sufficient number of research studies that (a) are of high methodological quality, (b) use appropriate research designs that allow for assessment of effectiveness, and (c) demonstrate meaningful effect sizes” ([59], p. 495).

This systematic review aims to determine if arts-based nursing education meets the criteria for evidence-based practice (EBP). It examines the extent to which rigorous research has been conducted on arts-based pedagogy in nursing, with attention to research design, methodological quality, and effect size [60,61,62]. As a critical review, this study explores the quality and credibility of quantitative research on arts-based nursing education. It aims to uncover potential methodological flaws or bias, make recommendations for future research, and inform practice in the field [63,64]. The paper takes a systematic approach to explore the impact of arts-based interventions on competence development as reflected in quantitative research. What are the reported effects on knowledge, skills, and attitudes resulting from art-based interventions? Is there scientifically robust research demonstrating their effectiveness [64]? The purpose of this review is to assess the effectiveness of art-based pedagogies in nursing and to support the concept of evidence-based nursing education [65].

2. Materials and Methods

This review follows the methodological approach for conducting systematic reviews as outlined by Kitchenham and Charters [66]. The approach includes the following stages: study selection, identification of research, quality assessment, data extraction, and data synthesis. The protocol for this systematic review was registered on INPLASY (INPLASY202440071).

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.1.1. Phenomena of Interest

As research on nursing education is the context of this study, the review encompasses all forms of training and development for nursing professionals, including secondary education in nursing degree programs and professional development. Secondary education in nursing degree programs as well as professional development are considered. The review also includes studies in which the participants were not exclusively nursing students or professionals.

This review focuses on arts-based pedagogy in nursing education. It includes studies in which learners receive works of visual art (painting, sculpture, graphics, photography, performance and media art, etc.), performing arts (theater, dance), music, film, or poetry. It also includes studies in which learners themselves create artifacts or actively engage in creative expressions such as theater, dance, narrative storytelling, etc. [67]. The review excludes methods that are not considered arts-based, such as photovoice, concept mapping, reflective writing, and standardized patient simulation using drama students. It considers interventions where the arts are integrated into regular nursing education, but not interventions limited to an examination context or self-contained art classes. Articles discussing the art of nursing, arts-based care methods, arts-based interventions in hospitals, or arts-based research methods in a nursing context are excluded.

2.1.2. Outcomes

This review examines competence development, defined as the process of enhancing knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to effectively perform tasks [68], with a focus on generic competency domains in nursing, such as professional attitude, clinical care, communication, and collaboration [33]. Only research that pertains to these domains is included, while studies that solely focus on learning experience and learner satisfaction, as well as research on learning and examination stress, are excluded.

2.1.3. Types of Studies

The review includes quantitative studies that enable the determination of causality between intervention and effect. It encompasses comparative studies with experimental or quasi-experimental designs, as well as non-experimental studies with a one-group pretest-posttest design [69]. Mixed-methods studies are included if they contain a relevant quantitative sub-study.

2.2. Literature Search and Screening

A systematic search for primary research studies was conducted in electronic databases relevant to nursing science, healthcare, and education. The databases searched were CINAHL, ERIC, Medline, PsycInfo, Scopus, and Web of Science. The Boolean phrase (nursing AND education OR nursing AND students) AND (art OR arts OR painting OR sculpture OR drawing OR music OR dance OR drama OR poetry OR photo* OR movie*) was applied to titles and abstracts. The full search strategy is displayed in Table S1. The database search was limited to articles with available abstracts and was supplemented by a manual backward search in relevant reviews [70].

To ensure the quality of the research, only peer-reviewed journal articles in English language published between January 1999 and December 2023, including electronic advance publications, were considered. This approach is in line with the growing body of relevant research since the mid-1990s [32]. Dissertations, book chapters, and other articles that might not have undergone independent review were excluded.

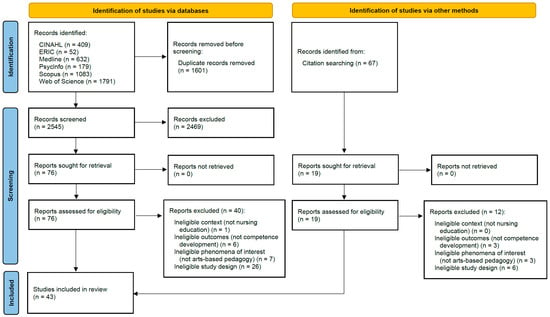

The database and manual searches together yielded an initial 2612 potentially relevant articles. Subsequently, titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion criteria, resulting in 95 articles in total for full-text screening. After the screening process, 43 articles remained for evaluation. Search outcomes are displayed in Figure 1, using standard PRISMA flow diagram [71]. Screening was conducted by the author and a second reviewer using a review software, the Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment, and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI) [72]. The concordance for title and abstract screening was initially established at a rate of 99.5% (12 conflicts). In the event that a conflict could not be resolved through discussion, the reviewers included the relevant studies for further examination [70,73]. The full-text screening yielded a 100% match.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for literature search and selection.

2.3. Quality Assessment

The Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) Standards for Evidence-Based Practices in Special Education [74] is the selected assessment tool for this review. Evidence assessment tools developed for health research are not entirely applicable to evaluate articles in education research [75]. The CEC Standards were chosen because they are specifically designed for pedagogical intervention studies and allow for a more rigorous appraisal than other approaches in education research [76,77,78].

The CEC Standards encompass important research on comparative studies and single-case research in the field, as presented by Gersten and colleagues [79], Horner and colleagues [80], and Lane and colleagues [81], as well as the criteria established by the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) [82]. The CEC Standards are a common assessment tool in educational research. They are not exclusive to the field of special education [77], but they have also been used for systematic reviews in adult and higher education (e.g., [83,84,85,86,87]).

The CEC Standards guide the identification of evidence-based practices (EBPs) using 28 quality indicators (QIs) for the methodological soundness of group comparison studies and single-subject studies. The QIs cover eight areas: Context and Setting, Participants, Intervention Agents, Description of Practice, Implementation Fidelity, Internal Validity, Outcome Measures/Dependent Variables, and Data Analysis (Table 1). A study is considered sound if it meets all QIs in full. The CEC Standards also provide a grid for classifying the evidence base of practices based on high-quality research [82].

Table 1.

CEC quality indicators. Source: [74].

Quality criteria sets must be adapted to the context and scope of the systematic review [58]. For this review, QIs 2.2 and 5.3 of the CEC Standards were excluded because they refer to requirements in special education and do not fit arts-based pedagogy. QIs 6.6 and 8.2 were also excluded because they apply to single-subject studies only. QIs 6.4, 6.8, and 6.9 are only applicable to group comparison studies.

The CEC standards should only be applied to experimental studies that meet the criteria for EBP [74]. However, this review includes non-experimental studies to identify methodological challenges and promising approaches in arts-based pedagogy. To assess the methodological quality of non-experimental studies, the CEC checklist was slightly modified. QI 6.5, originally intended for single-subject studies, is considered to be met if the study used a pretest-posttest-follow-up design, because such a design provides information about the long-term impact, stability, and causal effects of the intervention, which enhances validity [88].

The author and a second reviewer independently assessed all studies for methodological quality using extensive guidelines for interpreting the QIs [79,80,81,82]. The scoring was recorded in a quality indicator matrix that followed the CEC Standards [89]. Inter-rater agreement was calculated within the matrix at the indicator level to demonstrate the reliability of quality appraisal. The interrater-agreement percentage was initially 98.9% on average for all articles. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by the reviewers through mutual agreement [70]. The assessment results are presented for both comparative and non-experimental studies in Appendix A in Table A1 and Table A2, respectively.

The CEC Standards require that all relevant QIs for the research design be met for a study to qualify as methodologically sound [74,82]. However, this benchmark has been criticized for being overly rigorous [81,90]. This review is based on a moderate understanding of evidence because, in educational research, it is appropriate to consider knowledge that does not correspond to the gold standard of evidence-based argumentation [91]. The scoring method suggested by Lane and colleagues [81] is followed, and QIs are weighed and given partial credit if met. A 80% cut-off point is applied to comparative studies. Studies that achieve 80% of QIs, equivalent to a score of 6.4, qualify as potential EBPs. Non-experimental studies, which represent a lower level of evidence than comparative studies [92], must meet the modified CEC Standards by 90%, equivalent to a score of 7.2.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data were extracted using summary tables for all comparative (Appendix A, Table A3) and non-experimental studies (Appendix A, Table A4). A concise summary is presented in Table 2. For mixed-methods studies, data extraction was limited to the characteristics of the quantitative sub-studies. The extraction was performed by the second reviewer and verified for accuracy in full by the author. The variables used for summarization were as follows: (a) intervention type, (b) study design, (c) participant characteristics and sample size, (d) data collection, (e) outcome measurements, and (f) key findings.

Table 2.

Summary of studies.

All studies were assessed for the certainty of evidence and categorized as having positive, mixed, neutral, or negative effects. The following criteria were established a priori [74,82]. Due to the heterogeneous nature of interventions and study designs, effect sizes were not taken into account. Studies are classified as having positive effects if statistically significant increases are demonstrated for all dependent variables. Studies are classified as yielding mixed effects if there are statistically significant increases in some dependent variables but not in others. Effects are classified as neutral if the intervention did not result in a statistically significant improvement in any of the dependent variables. If competencies deteriorate, the effect is termed negative.

2.5. Data Synthesis

To determine if arts-based pedagogy qualifies as an evidence-based practice (EBP), studies beyond the threshold of quality assessment are grouped based on comparable interventions in terms of art form, procedure, and outcome. A differentiated approach is required due to the heterogeneity of studies [133]. The study follows the evidence-based classifications established by CEC [74], and the results are presented in Table A5 in Appendix A.

According to CEC Standards, EBPs must demonstrate positive effects supported by a minimum of two robust group comparison studies with random assignment. As non-random assignment of participants to groups raises the risk of selection bias, the CEC Standards mandate that EBPs show positive effects backed by four methodologically sound group comparison studies [82]. A body of work that fails to meet the criteria for evidence-based practice may be categorized as “potentially EBP”, “mixed evidence”, “insufficient evidence”, or “negative effects” [74].

3. Results

After the screening process, 43 studies were included in the review. Out of these, 13 comparative studies met the criteria for a sound study and were evaluated as an EBP.

3.1. Participants and Settings

Most of the reviewed studies are based on data from undergraduate nursing students at universities or colleges. In six cases, participant groups were interdisciplinary, including medical or social work students [97,111,117,125,131,132]. Two studies took place in a professional training context [118,122]. Sample sizes for group comparison studies range from 40 to 267, while for non-experimental studies they range from 9 to 307.

3.2. Independent Variables

The studies reviewed cover a wide range of intervention designs that are based on various art forms.

A total of 15 interventions utilize the visual arts, with art observation being the most common design. Art observation is typically conducted in a museum (e.g., [56,102,115]). Three interventions engaged participants in creative assignments [95,103,113].

With a total of 10 studies, drama is a well-researched form of arts-based pedagogy [104,128,129]. Students typically participate in role-play or improvisation.

The sample includes five studies that used music as a teaching tool (e.g., [40,105]) or incorporated music into practical care [99]. Four studies examine the effects of cinenurducation [53] using movies as instructional material (e.g., [121,123]).

Other learning environments include photography [126], poetry [122], storytelling (e.g., [116]), comics and graphic novels [114], or a combination of different art forms [106,120].

3.3. Dependent Variables

Sensory perception skills are of particular interest for research (e.g., [56,102,106,107]) with a total of 10 studies. Above all, the impact of art observation on observation skills is examined. Five studies examine cognitive skills (e.g., [115,117,129]). Other studies focus on communication skills (e.g., [56,119]), diagnostic skills [102], or clinical skills [40,127].

Pedagogy that is based on the dramatic arts is often the subject of effectiveness research on attitudes. Ten studies examining the impact of arts-based pedagogy on attitudes toward others were analyzed (e.g., [96,104,116,131]), as well as five studies concerning attitudes toward other nursing issues (e.g., [112,128]). The research also covers complex concepts such as empathy, which is discussed in six studies (e.g., [93,122,132]), and professional identity, which is discussed in three (e.g., [103,121]).

Besides competence development, some studies examine personality traits such as self-efficacy [103], tolerance for ambiguity [110,111], and self-transcendence [95,113]. Five studies have explored the impact of arts-based pedagogy on knowledge acquisition, indicating that this is a peripheral research area (e.g., [114,116,129]).

3.4. Research Designs

Out of the 43 studies examined, 21 were group comparison studies, five of which were conducted as quasi-experiments. The remaining 22 studies were non-experimental. In the entire sample, eight studies utilized a mixed-methods design.

3.5. Methodological Quality

The quality appraisal results are presented in Appendix A in Table A1 for experimental and quasi-experimental studies and in Appendix A in Table A2 for non-experimental studies.

Of the reviewed studies, two experimental studies meet the Qis in full [104,128]. Eleven additional comparative studies score 80% or higher on the Qis [93,94,95,102,105,108,121,122,127,129,132]. Thirteen out of the twenty-one comparison studies achieved a high level of methodological quality, with a weighted score of 6.4 Qis or higher. The remaining eight comparison studies were of moderate quality, scoring at least 5.2 Qis.

Non-experimental studies did not meet the 90% threshold specified for this review, with six studies receiving a mediocre rating of 5.6 Qis or higher.

Common methodological shortcomings in all types of studies include inadequate definitions of dependent variables, a lack of reliability, and the absence of evidence of validity. Out of 22 comparison studies, nine lack reliability, and 14 lack evidence of validity (e.g., [114]). Out of the 21 non-experimental studies, 16 rely on measurement tools that use self-developed questionnaires, face validity, or scales that were transferred without reflection (e.g., [56,95,111,116,117,118]). While some measurement tools lack psychometric data, others require considerable effort to verify because they are referenced in articles that are not available in English [93,103,108,120,121,123,131].

Controlling for internal validity is a common issue in non-experimental studies. Twenty non-experimental studies used a pretest–posttest design, while two studies also conducted a follow-up test [98,125]. Several non-experimental studies have inaccuracies in data analysis and reporting (e.g., [100]). Other studies have problems with reporting implementation fidelity or exposure, or do not provide an in-depth description of the intervention (e.g., [119,125]).

3.6. Effects

Out of the 21 group comparison studies, 14 report significant positive effects on skill levels and attitudes. Three studies show mixed results, lacking significant effects on some dependent variables [95,102,103,113]. Four interventions had no impact [109,123,128]. Although arts-based pedagogy may have a positive impact on students’ competencies, it is not necessarily superior to conventional teaching. In two cases, researchers note positive effects but do not identify significant differences in competence development between the experimental and control groups [103,128].

Out of the 22 non-experimental studies, nine reported significant positive effects on nursing knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Another nine studies showed mixed results for changes in skill levels and attitudes. Four interventions failed to achieve an effect [96,97,117,119]. The outcomes are not related to art forms. Even comparable interventions may lead to different results [110,111].

4. Discussion

Out of the 43 studies reviewed, 13 are related to potential EBP as they achieve an 80% score for methodological soundness according to CEC Standards (Appendix A, Table A1). Three of these studies apply a quasi-experimental design [95,122,132], while ten meet the gold-standard of evidence by experimental design [69]. Ten studies describe arts-based interventions with positive effects on knowledge, skills, or attitudes (Appendix A, Table A5).

The sample is heterogeneous in terms of the studies included. It covers a range of different art-based interventions that must be assessed individually for each art form and targeted outcome when classifying research as evidence-based. Due to its variety, arts-based pedagogy needs to be evaluated less by “what works” but by “what works, for whom, and in what circumstances” ([133], p. 218).

4.1. Efficacy of Non-Dramatic Arts

A creative bonding intervention that employed students’ collages and other objects in practical care yielded mixed results on self-transcendence and attitudes toward elders [105]. A multi-week Visual Arts Training at a museum significantly improved participants’ observational skills but not their diagnostic competency [102]. The sample includes two musical interventions that positively impacted competence development. One intervention aimed to improve auditory skills [105], while the other utilized a disco song as an aid in cardiac resuscitation [127]. Two studies successfully introduced movies to the classroom [94,121]. Both studies screened movies without debriefing, but they differed in the number of movies shown and their duration. The experiments aimed to achieve different outcomes, with one focusing on empathy and the other on professional identity. One intervention that yielded positive effects, is based on poetry [122].

Pedagogical approaches to nursing education that are based on visual arts, music, movies, or poetry cannot be classified as evidence-based because an EBP requires at least one methodologically sound study to support it [82].

The use of visual arts training in museum settings to enhance perceptual abilities is a popular practice in nursing education and has garnered significant attention from researchers [31]. However, this approach has yet to yield robust research findings. Similarly, the incorporation of movies in teaching (cinenurducation) has inspired several studies [54], yet tangible research outcomes remain elusive. Arts-based learning offers interesting opportunities, such as exploring underrepresented art forms like comics, and developing interdisciplinary competencies such as intercultural skills [114]. Dance may enhance communication and collaboration skills [134] and other competencies relevant to clinical leadership [135], but it lacks solid quantitative research representation.

4.2. Efficacy of Creative Drama

Six studies aim to investigate the effects of drama-based pedagogy on nursing competencies [93,108,129,132], with two of them receiving the highest possible quality rating [104,128]. The learning experience was organized in a workshop format using creative drama. All workshops, except for one [129], were led by experienced or certified researchers in creative drama. Participants received training in drama techniques (e.g., [108]) or improvisation techniques [132] and actively applied them by reenacting [128] or role-playing typical care situations (e.g., [93]). One study demonstrates positive effects on postmortem care knowledge and skills [129]. Four studies report positive results on attitudes and empathy, while one intervention was found to be ineffective [128].

Three methodologically sound experimental studies on the use of drama in nursing education have reported positive effects on empathy and involved a total of 183 participants across studies [93,108,132]. These findings suggest that drama-based pedagogy qualifies as an evidence-based practice in nursing education according to the CEC classification [74]. However, it is important to note that these results are limited to empathy as a dependent variable, and there is insufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of creative drama in changing attitudes.

Creative drama is highly significant in nursing education and research because it allows students to explore complex nursing scenarios in a safe and supportive environment [47]. Empathy is an essential nursing competence because it fosters patient trust and the development of a successful therapeutic relationship [136,137]. Identifying creative drama as an EBP in terms of empathy adds to less rigorous research on the potential of drama in nursing education. Drama can enhance understanding of situations in clinical practice and the patient experience through fostering empathy and emotional engagement [48].

4.3. Impact on Professional Identity and Skills

Eight high-quality studies address attitudes reflecting the importance of professional values and their transmission in nursing education [138]. The arts-based teaching interventions documented in these eight studies successfully addressed altruism, empathy, and moral sensitivity (e.g., [93,94,121,122]). For healthcare professionals, prosocial behavior is crucial, and interpersonal competencies are essential in forming their professional identity [138]. As a potential trigger of deep reflection [27], arts-based pedagogy is an effective alternative to common approaches to identity formation, which is predominantly linked to traditional classroom learning [139].

Two high-quality studies focus on perceptual skills. They report positive effects of a music-based approach on auditory skills [105] and mixed effects of visual arts training on observational skills [102]. Together with inconclusive results from less rigorous studies (e.g., [56,107,109]), these findings challenge expectations for arts-based perceptual skills training in nursing education [31,46] and limit the meaningful scope of application to reflectivity. Visual arts have also been used in medical education to improve visual literacy and enhance students’ observational and diagnostic skills [140,141]. As in nursing education, there is a lack of robust evidence on the development of competencies [142,143,144,145,146].

4.4. Challenges and Implications for Research

The review supports previous findings that suggest a lack of methodological quality and rigor in research on arts-based nursing education [32,43]. Although there is a substantial body of literature, there is a clear lack of evidence to support the effectiveness of arts-based pedagogy in terms of competency development.

The results suggest a requirement for high-quality research on arts-based teaching methods. Nevertheless, there are various obstacles to implementing evidence-based practice in this area that subpar studies are unable to overcome convincingly. Arts-based practices pose a challenge to the standardization of interventions and replication [147]. Comparative studies may face difficulties in drawing generalizable conclusions due to variability in implementation fidelity, instructor expertise, and student engagement, which can introduce heterogeneity. Arts-based pedagogy is highly context-dependent and influenced by factors such as teachers’ attitudes and students’ experiences and preferences [27,148]. Contextual variables may interact with the intervention, making it challenging to isolate the effects of arts-based practices. Arts-based pedagogy encompasses a wide variety of artistic mediums, teaching approaches, and instructional strategies. Each practice may have unique characteristics, making direct comparisons between interventions difficult.

To assess the impact of arts-based interventions on competence development, reliable observational data and tested scales are necessary. Sound psychometry is needed to establish contemporary measurement tools for outcomes that arts-based methods typically address [149]. The high-quality studies examined in this review predominantly employ established measurement instruments. In medical education, there are a variety of quantitative scales for assessing observation skills, as well as psychometric scales used to assess the impact of arts-based pedagogies on ambiguity tolerance, communication skills, empathy, and mindfulness [150]. It is recommended that nursing education researchers prioritize the development, validation, and application of robust psychometric instruments tailored to arts-based educational interventions. This will ensure that future studies can more accurately measure and demonstrate the true impact of these pedagogies and their unique characteristics on nursing competencies.

4.5. Requirements and Implications for Educational Practice

Professional standards for nurse educator practice emphasize the importance of employing evidence-based approaches to curriculum design, choice of teaching strategies, and assessment methods [151]. The findings presented in this review suggest that educators expand their teaching repertoire, but integrate arts-based teaching methods with caution. While the potential benefits of arts-based pedagogy cannot be dismissed, the lack of robust evidence necessitates a measured approach. It is recommended that educators engage in ongoing professional development to refine their understanding and implementation of arts-based methods [152]. This should include training on how to effectively integrate these approaches into the curriculum and how to critically evaluate their impact on student learning and competence development. Furthermore, it is of paramount importance for nursing educators to advocate for and adhere to evidence-based practice [151]. This encompasses not only the application of research findings to practice but also the contribution to research itself [153].

4.6. Limitations

The quality appraisal is based on the CEC Standards and categorization scheme for EBP [74,82], with a less rigorous threshold applied [81]. The scope of the review and validity check is limited to English language publications. This approach to quality appraisal is not conclusive. Notably, the selection of quality evaluation tools impacts evaluation findings. Utilizing a different assessment tool and altering the weighting scheme will alter results [154]. Tools for assessing evidence specific to the social sciences are still deficient [75]. The field of education is currently engaged in intense debate about the definition of evidence and the standards that should be applied [91,147,155,156]. The concept of evidence in education extends beyond (quasi-)experimental findings. Unlike in medical science, which provides a variety of assessment tools, comparative studies are rare in educational research. Education is a social system with comparatively weaker validity [156]. As it falls into the category of the “harder-to-do sciences” ([147], p. 424), research on arts-based pedagogy requires specific standards for quality appraisal that do not yet exist.

This review examines the extent to which arts-based pedagogy improves the competencies of nursing students. It does not address the impact of arts-based pedagogy on the learning environment or other factors that contribute to learning success, such as learner engagement [157]. Successful arts-based pedagogy is largely based on disrupting behavior patterns and beliefs that facilitate the learning process [158,159,160]. Arts-based approaches are believed to benefit from experiential learning, multisensory learning, and emotional engagement [26,161,162]. However, their impact on learners and their influence on competence development require refined quantitative assessment methods and a wider range of methodologically sound comparative studies to build a more definitive evidence base for arts-based pedagogy.

5. Conclusions

Given the increasing recognition of non-traditional teaching methods in nursing education and the necessity to prepare students for the complexities of modern healthcare settings, research on arts-based pedagogy in nursing education is a growing area of interest. This research area is significant because it explores innovative teaching methods that can enhance nursing education and improve patient outcomes. However, there is a lack of evidence regarding the development of competence related to interventions and outcomes relevant to nursing practice, despite the variety of approaches stemming from different art forms.

This review aimed to evaluate whether arts-based approaches to nursing education improve nursing competence and meet the criteria for EBP. The review identified 43 quantitative studies that explored the impact of arts-based pedagogy on the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of nursing students. Thirteen comparative studies met the CEC Standards for high-quality research. Based on the CEC classification scheme, creative drama is considered an EBP, while other forms of arts-based pedagogy do not have enough sound studies to qualify as an EBP.

The findings suggest that the high expectations toward arts-based pedagogy in nursing education should be reconsidered in light of the evidence base. It is important to conduct high-quality research in this field to gain a better understanding of its effectiveness. This effort is critical to advancing arts-based pedagogy from an innovative educational experiment to a foundational, evidence-based practice in nursing education.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nursrep14020083/s1, Table S1: Database search.

Funding

This research was supported by the University of Applied Sciences Berlin.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Reporting follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [71].

Acknowledgments

The author would like to extend her sincere appreciation to Lilith Merle Meyer, research assistant at the University of Applied Sciences Berlin, for her invaluable assistance in screening, quality assessment, and data extraction throughout the course of this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Quality assessment results for comparative studies.

Table A1.

Quality assessment results for comparative studies.

| 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | No. of QIs Met | Effects | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | 1.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 8.3 | Absolute | 80% Weighted | Positive | Mixed | Neutral | Negative |

| Basit et al. (2023) [93] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 6 | 7.67 | • | |||||

| Briggs and Abell (2012) [94] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | 6 | 7.33 | • | |||||

| Chen and Walsh (2009) [95] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 5 | 7.00 | • | |||||||

| Guo et al. (2021) [102] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 7 | 7.50 | • | ||||

| HadaviBavili and İlçioğlu (2024) [103] | • | • | NA | NA | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 4 | 5.50 | • | ||||||||||

| Hançer Tok and Cerit (2021) [104] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 8 | 8.00 | • | |||

| Honan Pellico et al. (2012) [105] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 6 | 7.33 | • | |||||

| Ince and Çevik (2017) [40] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | 4 | 6.33 | • | |||||||

| Kahriman et al. (2016) [108] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 6 | 7.33 | • | |||||||

| Kirklin et al. (2007) [109] | • | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | 4 | 5.83 | • | |||||||||

| Lamet et al. (2011) [113] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 5 | 6.00 | • | |||||||||||

| Lesińska-Sawicka (2023) [114] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 4 | 6.17 | • | ||||||||||

| Nease and Haney (2018) [118] | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 3 | 5.17 | • | ||||||||||||

| Park and Cho (2021) [121] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 7 | 7.67 | • | |||||

| Rashidi et al. (2022) [122] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 6 | 6.83 | • | ||||||

| Röhm et al. (2017) [123] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 3 | 5.83 | • | ||||||||||

| Tastan et al. (2017) [127] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 7 | 7.83 | • | ||||

| Tokur Kesgin and Hançer Tok (2023) [128] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 8 | 8.00 | • | |||

| Uzun and Cerit (2023) [129] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 6 | 6.50 | • | |||||

| Wikström (2001) [130] | • | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | 4 | 5.67 | • | ||||||||||

| Zelenski et al. (2020) [132] | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | 5 | 6.50 | • | |||||||

| Total | 21/ 21 | 18/ 21 | NA | 16/ 21 | 20/ 21 | 18/ 21 | 13/ 21 | 10/ 21 | 14/ 21 | NA | 17/ 21 | 21/ 21 | 18/ 21 | 16/ 21 | NA | NA | NA | 14/ 21 | 18/ 21 | 21/ 21 | 16/ 21 | 20/ 21 | 20/ 21 | 12/ 21 | 8/ 21 | 21/ 21 | NA | 17/ 21 | ||||||

Note. NA = not applicable.

Table A2.

Quality assessment results for non-experimental studies.

Table A2.

Quality assessment results for non-experimental studies.

| 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | No. of QIs Met | Effects | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | 1.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 8.3 | Absolute | 90% Weighted | Positive | Mixed | Neutral | Negative |

| Dickens et al. (2018) [96] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | • | NA | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 4 | 6.33 | • | ||||||||||

| Dingwall et al. (2017) [97] | • | NA | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | 2 | 4.17 | • | |||||||||||||

| Eaton and Donaldson (2016) [98] | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | NA | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 5 | 7.00 | • | |||||||

| Emory et al. (2021) [99] | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | 3 | 5.83 | • | |||||||||||

| Gazarian et al. (2014) [100] | • | • | NA | • | NA | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 3 | 5.00 | • | |||||||||||

| Grossman et al. (2014) [101] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | 3 | 5.33 | • | ||||||||||||||

| Honan Pellico et al. (2014) [106] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | 3 | 5.67 | • | |||||||||||

| Honan et al. (2016) [107] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 3 | 6.00 | • | ||||||||||

| Klugman and Beckmann-Mendez (2015) [110] | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | 2 | 4.00 | • | ||||||||||||||||

| Klugman et al. (2011) [111] | • | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | 4 | 5.67 | • | |||||||||||

| Kyle et al. (2023) [112] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 5 | 6.00 | • | ||||||||||

| Lovell et al. (2021) [115] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | 3 | 5.17 | • | |||||||||||||

| Moore and Miller (2020) [116] | • | NA | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | 3 | 5.00 | • | |||||||||||||

| Nash et al. (2020) [117] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | 3 | 5.00 | • | ||||||||||||||

| Neilson and Reeves (2019) [119] | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | 3 | 3.67 | • | |||||||||||||||||

| Özcan et al. (2011) [120] | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | 3 | 4.50 | • | |||||||||||||||

| Shieh (2005) [124] | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | 4 | 5.50 | • | ||||||||||||

| Sinha et al. (2015) [125] | • | NA | NA | • | NA | • | NA | NA | • | • | • | 1 | 1.83 | • | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Slota et al. (2018) [38] | • | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | 4 | 5.17 | • | ||||||||||||

| Slota et al. (2022) [56] | • | NA | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | 3 | 4.67 | • | |||||||||||||

| Stupans et al. (2019) [126] | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 3 | 4.83 | • | ||||||||||||

| Yamauchi et al. (2017) [131] | • | • | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • | NA | • | • | • | NA | NA | NA | • | • | • | • | • | 5 | 6.67 | • | ||||||||||

| Total | 22/ 22 | 12/ 22 | NA | 16/ 22 | 20/ 22 | 18/ 22 | 8/ 22 | 8/ 22 | 12/ 22 | NA | 14/ 22 | 22/ 22 | 17/ 22 | NA | 2/ 22 | 1/ 22 | 0/ 22 | NA | NA | 22/ 22 | 10/ 22 | 19/ 22 | 21/ 22 | 6/ 22 | 5/ 22 | 16/ 22 | 1/ 22 | 15/ 22 | ||||||

Note. NA = not applicable.

Table A3.

Summary of comparative studies.

Table A3.

Summary of comparative studies.

| Effects | No. of QIs Met | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Intervention | Study Design | Participants | Data Collection | Outcome | Measurements | Key Findings | Positive | Mixed | Neutral | Negative | Absolute | 80% Weighted |

| Basit et al. (2023) [93] Turkey | Drama Roleplay | Exp. | Nursing students n = 49 | Q | Altruism Empathy | Altruism Scale Jefferson Scale of Empathy for Nursing Students (JSENS) | Significant increase in altruism and empathy No enduring effect | • | 6 | 7.67 | |||

| Briggs and Abell (2012) [94] USA | Movie | Exp. | Junior nursing students n = 49 | Q | Empathy | Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSE) | Significant increase in empathy | • | 6 | 7.33 | |||

| Chen and Walsh (2009) [95] Taiwan | Visual art | Quasi-exp | Fourth-year nursing students n = 194 | Q | Self-transcendence Attitudes toward elders | Self-transcendence scale (STS) Revised Kogan’s attitudes toward old people scale (RKAOP) | Significantly more positive attitude toward elders No effect on self-transcendence | • | 5 | 7.00 | |||

| Guo et al. (2021) [102] China | Visual art | Exp. | First-year nursing students in master program n = 99 | Q | Observational skills Diagnostic skills | Clinical image test | Significant increase of observational skills Trend toward improvement of diagnostic skills | • | 7 | 7.50 | |||

| HadaviBavili and İlçioğlu (2024) [103] Turkey | Visual art | Exp. | First-year nursing and mid-wifery students n = 181 | Q | Attitudes and self-efficacy toward anatomy courses | Anatomy attitude scale Anatomy self-efficacy scale | No significant effect | • | 4 | 5.50 | |||

| Hançer Tok and Cerit (2021) [104] Turkey | Drama Roleplay | Exp. | First-year Bachelor of Nursing Science students n = 40 | Q | Attitudes toward caring for dying patients | Frommelt Attitude Scale for Caring for Dying (FATCOD) | Significantly more positive attitude toward dying patients | • | 8 | 8.00 | |||

| Honan Pellico et al. (2012) [105] USA | Music | Exp. | First-year nursing students in master program n = 78 | Obs. | Auditory skills | N/A | Significant improvement of organ identification and sound interpretation | • | 6 | 7.33 | |||

| Ince and Çevik (2017) [40] Turkey | Music | Exp. | First-year nursing students n = 73 | Obs. | Blood draw skills | Skill controls list | Significantly decreased anxiety levels Improved blood draw skills | • | 4 | 6.33 | |||

| Kahriman et al. (2016) [108] Turkey | Drama Roleplay Improvisation | Exp. | Practicing nurses n = 48 | Q | Empathy | Empathic Skill Scale (ESS) | Significant increase in empathy | • | 6 | 7.33 | |||

| Kirklin et al. (2007) [109] UK | Drama | Quasi-exp. | Practicing nurses and doctors n = 68 | Obs. | Observational skills | N/A | No significant effect | • | 4 | 5.83 | |||

| Lamet et al. (2011) [113] USA | Visual arts | Quasi-exp | Junior and senior nursing students n = 98 | Q | Attitudes toward older people Self-transcendence Willingness to serve | Self-Transcendence Scale (STS) Attitudes toward Old People Scale | Significant improvement in attitudes toward older people Trend to increased willingness to serve | • | 5 | 6.00 | |||

| Lesińska-Sawicka (2023) [114] Poland | Comics Graphic novels | Exp. | First-year nursing students n = 62 | Q | Knowledge of cultural issues | N/A | Significant increase in knowledge | • | 4 | 6.17 | |||

| Nease and Haney (2018) [118] USA | Visual art | Exp. | Practicing nurses n = 36 | Obs. | Observation skills Problem description and identification skills | N/A | Significant improvement of observation skills Significant improvement of problem description and identification skills | • | 3 | 5.17 | |||

| Park and Cho (2021) [121] South Korea | Movies | Exp. | Second year undergraduate nursing students n = 29 | Q | Professional nursing identity Professional nursing values | Perception of nursing checklist Professional nursing values scale | Significant improvement in perception of nursing and professional nursing values | • | 7 | 7.67 | |||

| Rashidi et al. (2022) [122] Iran | Poetry | Quasi-exp. | Practicing nurses n = 108 | Q | Moral sensitivity | Nursing Moral Sensitivity Questionnaire (MSQ) | Significantly enhanced sensitivity | • | 6 | 6.83 | |||

| Röhm et al. (2017) [123] Germany | Movies | Quasi-exp. | Bachelor and master students in Rehabilitation Sciences n = 51 | Q | Attitudes and social distancing toward stigmatized groups | Social Distance Scale Community Attitudes toward the Mentally Ill (CAMI) | No significant effect | • | 3 | 5.83 | |||

| Tastan et al. (2017) [127] Turkey | Music | Exp. | Second-year nursing school students n = 77 | Obs. | Cardiac resuscitation skills | N/A | Significantly improved performance of cardiac resuscitation | • | 7 | 7.83 | |||

| Tokur Kesgin and Hançer Tok (2023) [128] Turkey | Drama Roleplay | Exp. | Fourth-year undergraduate nursing science students n = 78 | Q | Attitudes toward violence against women | Violence Against Women Attitude Scale (ÍSKEBE) | No significant effect | • | 8 | 8.00 | |||

| Uzun and Cerit (2023) [129] Turkey | Drama Improvisation Roleplay | Exp. | Third-year undergraduate nursing science students n = 70 | Q Obs. | Postmortem care knowledge and skills | Postmortem care knowledge test (PCKT) Postmortem care skills checklist (PCSCL) | Significantly improved postmortem knowledge and skill levels Enduring effect | • | 6 | 6.50 | |||

| Wikström (2001) [130] Sweden | Visual art | Exp. | First year nursing students n = 267 | Q | Perception of good nursing care | Wheel Questionnaire | Significantly improved understanding of good nursing care | • | 4 | 5.67 | |||

| Zelenski et al. (2020) [132] USA | Drama | Quasi-exp. (MMD) | Students in health professions training programs (mainly nursing, pharmacy, medical) n = 86 | Q | Interprofessional empathy | Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) Consultative and Relational Empathy (CARE) Ekman Facial Action Coding System | Significant enhancement of interprofessional empathy | • | 5 | 6.50 | |||

Note. Exp. = experimental; MMD = mixed-methods design; N/A = not applicable; Obs. = observation; Q = questionnaire.

Table A4.

Summary of non-experimental studies.

Table A4.

Summary of non-experimental studies.

| Effects | No. of QIs Met | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Intervention | Study Design | Participants | Data Collection | Outcome | Measurements | Key Findings | Positive | Mixed | Neutral | Negative | Absolute | 90% Weighted |

| Dickens et al. (2018) [96] UK | Movies | Non-exp. (MMD) | Undergraduate and postgraduate mental health nursing and counselling students n = 66 | Q | Attitudes toward people with PBD Knowledge about people with PBD | Borderline Personality Disorder Questionnaire | Minor changes in knowledge and attitudes | • | 4 | 6.33 | |||

| Dingwall et al. (2017) [97] UK | Drama | Non-exp. (MMD) | Third-year nursing and social work students n = 63 | Q | Attitudes toward older people | Self-developed questionnaire | Significant attitudinal changes among social work students only | • | 2 | 4.17 | |||

| Eaton and Donaldson (2016) [98] USA | Drama | Non-exp. | Second- and third-semester nursing students n = 12 | Q | Attitudes toward older adults | Attitudes Toward Old People Scale (KOP) Refined Version of the Aging Semantic Differential (rASD) | Significant improvement in attitudes | • | 5 | 7.00 | |||

| Emory et al. (2021) [99] USA | Music | Non-exp. (MMD) | First-year bachelor nursing students n = 18 | Q | Attitudes toward older adults | Perspectives on Caring for Older Patients (PCOP) Modified Kogan’s Attitudes toward Old People Scale (MKOP) | No significant effect for aggregate variables relating to attitudes toward older adults | • | 3 | 5.83 | |||

| Gazarian et al. (2014) [100] USA | Digital storytelling | Non-exp. | Senior-level nursing students n = 36 | Q | Patient advocacy | Protective Nursing Advocacy Scale (PNAS) | Increase in perceptions of patient advocacy | • | 3 | 5.00 | |||

| Grossman et al. (2014) [101] USA | Visual art | Non-exp. | Nursing students n = 19 | Q | Mindfulness Observational skills | Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) Clinical Picture Assessment (CPA) | Significant improvement of mindfulness Significant improvement of observational skills | • | 3 | 5.33 | |||

| Honan Pellico et al. (2014) [106] USA | Visual art Music | Non-exp. | Fourth-year bachelor nursing students n = 23 | Obs. | Perceptual aptitude skill (auditory and visual) | N/A | Improved observational skills Significant increase in auscultative interpretive skills | • | 3 | 5.67 | |||

| Honan et al. (2016) [107] USA | Visual art Music | Non-exp. | Students in an accelerated nursing master’s program for non-nursing college graduates n = 39 | Obs. | Perceptual aptitude skill (auditory and visual) | N/A | Significantly improvement in most observational skills Significant increase in some auscultative interpretive skills No enduring effects | • | 3 | 6.00 | |||

| Klugman and Beckmann-Mendez (2015) [110] USA | Visual art | Non-exp. | Undergraduate and graduate nursing students, medical students n = 19 | Q Obs. | Tolerance of ambiguity Attitude toward communication Observation skills | Variation of Budner’s Tolerance of Ambiguity Scale Communication Skills Attitude Scale (CSAS) | No significant effect on tolerance of ambiguity No significant effect on interest in communication Significant improvement of observational skills | • | 2 | 4.00 | |||

| Klugman et al. (2011) [111] USA | Visual art | Non-exp. | Undergraduate and graduate nursing students, different level medical students n = 32 | Q Obs. | Observational skills Tolerance for ambiguity | Variation of Budner’s Tolerance of Ambiguity Scale Communication Skills Attitude Scale (CSAS) | Significant improvement in observational skills Significant increase in tolerance for ambiguity | • | 4 | 5.67 | |||

| Kyle et al. (2023) [112] UK | Drama | Non-exp. | Undergraduate nursing students n = 175 | Q | Attitudes toward interprofessionalism and nursing advocacy | Attitudes toward Healthcare Teams Scale (ATHCTS) Protective Nursing Advocacy Scale (PNAS) | Significant improvement in attitudes toward interprofessionalism and nursing advocacy | • | 5 | 6.00 | |||

| Lovell et al. (2021) [115] USA | Visual art | Non-exp. | Traditional and accelerated first-year nursing students n = 218 | Q | Critical thinking (metacognitive awareness) | Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (MAI) | Significant increase in metacognitive awareness | • | 3 | 5.17 | |||

| Moore and Miller (2020) [116] USA | Video storytelling | Non-exp. | Second-degree nursing students n = 88 | Q | Knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes related to care for seriously ill people | Adapted Story Experience Questionnaire | Significant increase in knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes related to care for seriously ill people | • | 3 | 5.00 | |||

| Nash et al. (2020) [117] Australia | Drama Roleplay | Non-exp. (MMD) | Students from multiple health professions n = 65 | Q | Confidence and understanding in challenging situations | Self-developed questionnaire | Increased confidence and understanding in challenging situations | • | 3 | 5.00 | |||

| Neilson and Reeves (2019) [119] UK | Drama | Non-exp. (MMD) | First-year nursing students n = 100 | Q | Communication skills | Self-developed questionnaire | Improved communication skills | • | 3 | 3.67 | |||

| Özcan et al. (2011) [120] Turkey | Miscellaneous | Non-exp. | Third class and senior nursing students n = 48 | Q | Empathic skills | Empathic Skill Scale | Significant increase in empathic skills | • | 3 | 4.50 | |||

| Shieh (2005) [124] USA | Story writing Storytelling | Non-exp. (MMD) | Associate Degree in Nursing students n = 16 | Q | Nursing knowledge | Self-developed questionnaire | Significant improvement in five areas of nursing knowledge | • | 4 | 5.50 | |||

| Sinha et al. (2015) [125] USA | Visual art | Non-exp. | Mainly third-year nursing and medical students n = 36 | Q | Attitudes toward interprofessional collaboration Attitudes toward end-of-life care | Self-developed questionnaire | Significantly improved attitude toward interprofessional collaboration Significantly improved attitude toward end-of-life care | • | 1 | 1.83 | |||

| Slota et al. (2018) [38] USA | Visual art | Non-exp. | Post-Master Doctor of Nursing Practice students n = 9 | Q | Observation skills Communication skills | Self-developed Visual Intelligence Assessment Tool (VIA) | Significantly improved attitude toward the relevance of observational skills Improved observational skills Deteriorated communication skills | • | 4 | 5.17 | |||

| Slota et al. (2022) [56] USA | Visual art | Non-exp. | Post-Master Doctor of Nursing Practice and Clinical Nurse Leader graduate students n = 72 | Q Obs. | Observational skills Communication skills | Self-developed Visual Intelligence Assessment Tool (VIA) Image Assessment | No change in overall visual intelligence scores Significant improvement of observational skills | • | 3 | 4.67 | |||

| Stupans et al. (2019) [126] Australia | Photo-essay | Non-exp. (MMD) | First year Bachelor of Nursing students n = 77 | Q | Reflective thinking | Reflective Thinking Questionnaire | Significant increase in understanding and critical reflection Increase in reflection | • | 3 | 4.83 | |||

| Yamauchi et al. (2017) [131] Japan | Visual art | Non-exp. | Nursing students, social work students n = 307 | Q | Attitudes toward people with mental health problems | Semantic Differential Attitude Scale regarding people with mental health problems | Significantly improved attitudes toward people with mental health problems | • | 5 | 6.67 | |||

Note. Exp. = experimental; MMD = mixed-methods design; N/A = not applicable; Obs. = observation; Q = questionnaire.

Table A5.

Summary of high-quality studies.

Table A5.

Summary of high-quality studies.

| Effects | No. of QIs Met | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Intervention | Study Design | Participants | Data Collection | Outcome | Measurements | Key Findings | Positive | Mixed | Neutral | Negative | Absolute | 80% Weighted |

| Chen and Walsh (2009) [95] Taiwan | Visual art | Quasi-exp. | Fourth-year nursing students n = 194 | Q | Self-transcendence Attitudes toward elders | Self-transcendence scale (STS) Revised Kogan’s attitudes toward old people scale (RKAOP) | Significantly more positive attitude toward elders No effect on self-transcendence | • | 5 | 7.00 | |||

| Guo et al. (2021) [102] China | Visual art | Exp. | First-year nursing students in master program n = 99 | Q | Observational skills Diagnostic skills | Clinical image test | Significant increase of observational skills Trend toward improvement of diagnostic skills | • | 7 | 7.50 | |||

| Briggs and Abell (2012) [94] USA | Movies | Exp. | Junior nursing students n = 49 | Q | Empathy | Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSE) | Significant increase in empathy | • | 6 | 7.33 | |||

| Park and Cho (2021) [121] South Korea | Movies | Exp. | Second year undergraduate nursing students n = 29 | Q | Professional nursing identity Professional nursing values | Perception of nursing checklist Professional nursing values scale | Significant improvement in perception of nursing and professional nursing values | • | 7 | 7.67 | |||

| Honan Pellico et al. (2012) [105] USA | Music | Exp. | First-year nursing students in master program n = 78 | Obs. | Auditory skills | N/A | Significant improvement of organ identification and sound interpretation | • | 6 | 7.33 | |||

| Tastan et al. (2017) [127] Turkey | Music | Exp. | Second-year nursing school students n = 77 | Obs. | Cardiac resuscitation skills | N/A | Significantly improved performance of cardiac resuscitation | • | 7 | 7.83 | |||

| Rashidi et al. (2022) [122] Iran | Poetry | Quasi-exp. | Practicing nurses n = 108 | Q | Moral sensitivity | Nursing Moral Sensitivity Questionnaire (MSQ) | Significantly enhanced sensitivity | • | 6 | 6.83 | |||

| Basit et al. (2023) [93] Turkey | Drama Roleplay | Exp. | Nursing students n = 49 | Q | Altruism Empathy | Altruism Scale Jefferson Scale of Empathy for Nursing Students (JSENS) | Significant increase in altruism and empathy No enduring effect | • | 6 | 7.67 | |||

| Hançer Tok and Cerit (2021) [104] Turkey | Drama Roleplay | Exp. | First-year Bachelor of Nursing Science students n = 40 | Q | Attitudes toward caring for dying patients | Frommelt Attitude Scale for Caring for Dying (FATCOD) | Significantly more positive attitude toward dying patients | • | 8 | 8.00 | |||

| Kahriman et al. (2016) [108] Turkey | Drama Roleplay Improvisation | Exp. | Practicing nurses n = 48 | Q | Empathy | Empathic Skill Scale (ESS) | Significant increase in empathy | • | 6 | 7.33 | |||

| Tokur Kesgin and Hançer Tok (2023) [128] Turkey | Drama Roleplay | Exp. | Fourth-year undergraduate nursing science students n = 78 | Q | Attitudes toward violence against women | Violence Against Women Attitude Scale (ÍSKEBE) | No significant effect | • | 8 | 8.00 | |||

| Uzun and Cerit (2023) [129] Turkey | Drama Improvisation Roleplay | Exp. | Third-year undergraduate nursing science students n = 70 | Q Obs. | Postmortem care knowledge and skills | Postmortem care knowledge test (PCKT) Postmortem care skills checklist (PCSCL) | Significantly improved postmortem knowledge and skill levels Enduring effect | • | 6 | 6.50 | |||

| Zelenski et al. (2020) [132] USA | Drama | Quasi-exp. (MMD) | Students in health professions training programs (mainly nursing, pharmacy, medical) n = 86 | Q | Interprofessional empathy | Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) Consultative and Relational Empathy (CARE) Ekman Facial Action Coding System | Significant enhancement of interprofessional empathy | • | 5 | 6.50 | |||

Note. Exp. = experimental; MMD = mixed-methods design; N/A = not applicable; Obs. = observation; Q = questionnaire.

References

Note: References marked with an asterisk (*) indicate studies included in the review.

- Hirao, M. “The Art of Nursing” by Florence Nightingale, published by Claud Morris Books Limited and printed in 1946, which is considered a draft of “Notes on Nursing”. Nihon Ishigaku Zasshi [J. Jpn. Hist. Med.] 2000, 46, 246–255. [Google Scholar]

- Dade, L.; Wolf, L.K. A new approach to the teaching of nursing arts. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 1946, 46, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carper, B.A. Fundamental patterns of knowing in nursing. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1978, 1, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, Z.C. Exploration of artistry in nursing teaching activities. Nurse Educ. Today 2014, 34, 924–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amendolair, D. Art and science of caring of nursing: Art-based learning. Int. J. Hum. Caring 2021, 25, 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Badowski, D. Trends in the art and science of nursing education: Responding to the life-changing events of 2020. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2021, 42, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moseley, S.; Belcher, H.C. Art in the nursing curriculum. Nurs. Outlook 1955, 3, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reed, P.G. Liberal arts and professional nursing education: Integrating knowledge and wisdom. Nurse Educ. 1987, 12, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darbyshire, P. Understanding caring through arts and humanities: A medical/nursing humanities approach to promoting alternative experiences of thinking and learning. J. Adv. Nurs. 1994, 19, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vande Zande, G.A. The liberal arts and professional nursing: Making the connections. J. Nurs. Educ. 1995, 34, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, L.; Gaufberg, E.; King, B. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education; Association of American Medical Colleges: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- (WHO) World Health Organization. Global Competency and Outcomes Framework for Universal Health Coverage; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034662 (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Staricoff, R.L. Arts in health: The value of evaluation. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 2006, 126, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKie, A. Using the arts and humanities to promote a liberal nursing education: Strengths and weaknesses. Nurse Educ. Today 2012, 32, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archibald, M.M.; Caine, V.; Scott, S.D. Intersections of the arts and nursing knowledge. Nurs. Inq. 2017, 24, e12153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damsgaard, J.B. Integrating the arts and humanities into nursing. Nurs. Philos. 2020, 22, e12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.J. Nursing: The Philosophy and Science of Caring; Little, Brown and Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy, L.; Duffy, A. Holistic practice: A concept analysis. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2008, 8, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenk, J.; Chen, L.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Cohen, J.; Crisp, N.; Evans, T.; Fineberg, H.; Garcia, P.; Ke, Y.; Kelley, P.; et al. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010, 376, 1923–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones-Schenk, J. Designing education for learning activation. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2017, 48, 539–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, L. Aesthetic learning about, in, with and through the arts: A curriculum study. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2012, 31, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulou-Zormpala, M. Aesthetic teaching: Seeking a balance between teaching arts and teaching through the arts. Arts Educ. Policy Rev. 2012, 113, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, K.L.; Chernomas, W.M. Arts-based learning: Analysis of the concept for nursing education. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Sch. 2013, 10, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller-Skau, M.; Lindstøl, F. Arts-based teaching and learning in teacher education: “Crystallising” student teachers’ learning outcomes through a systematic literature review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 109, 103545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisolm, M.S.; Kelly-Hedrick, M.M.; Wright, S.M. How visual arts-based education can promote clinical excellence. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, K.L.; Chernomas, W.M.; McMillan, D.E.; Morin, F.L. The arts as a catalyst for learning with undergraduate nursing students: Findings from a constructivist grounded theory study. Arts Health 2020, 12, 250–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obara, S.; Perry, B.; Janzen, K.J.; Edwards, M. Using arts-based pedagogy to enrich nursing education. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2021, 17, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, B. Wirkfaktoren menschlicher Veränderungsprozesse: Das ModiV in allgemeiner und kunstbezogener Beratung, Psychotherapie und Pädagogik [Effective Factors of Human Change Processes: The ModiV in General and Art-Related Counseling, Psychotherapy and Education]; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista, K.; Macabasag, R.L.A.; Capili, B.; Castro, T.; Danque, M.; Evangelista, H.; Rivero, J.A.; Gonong, M.K.; Diño, M.J.; Cajayon, S. Effects of classical background music on stress, anxiety, and knowledge of Filipino baccalaureate nursing students. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Sch. 2017, 14, 20160076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, A.; Curtis, M. A descriptive qualitative study of student learning in a psychosocial nursing class infused with art, literature, music, and film. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Sch. 2008, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhammoumi, C.V.; Kellam, B. Art images in holistic nursing education. Religions 2017, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, K.L.; Chernomas, W.M.; McMillan, D.E.; Morin, F.L.; Demczuk, L. Effectiveness and experience of arts-based pedagogy among undergraduate nursing students: A mixed methods systematic review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2016, 14, 139–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wit, R.F.; de Veer, A.J.; Batenburg, R.S.; Francke, A.L. International comparison of professional competency frameworks for nurses: A document analysis. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydo, S.K.; Marcyjanik, D.L.; Zorn, C.R.; Hooper, N.M. Art as a scaffolding teaching strategy in baccalaureate nursing education. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Sch. 2007, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, J.; Alvarez, S.E.; Alexander, M.B. Ways of seeing: Using the visual arts in nursing education. J. Nurs. Educ. 2010, 49, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acai, A.; McQueen, S.A.; McKinnon, V.; Sonnadara, R.R. Using art for the development of teamwork and communication skills among health professionals: A literature review. Arts Health 2017, 9, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutter, S.L.; Pucino, C.L.; Jarecke, J.L. Arts-based learning strategies in clinical postconference: A qualitative study. J. Nurs. Educ. 2018, 57, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- * Slota, M.; McLaughlin, M.; Bradford, L.; Langley, J.F.; Vittone, S. Visual intelligence education as an innovative interdisciplinary approach for advancing communication and collaboration skills in nursing practice. J. Prof. Nurs. 2018, 34, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, E.E.; Ahn, J.; Kang, J.; Seok, Y. The development and application of drama-combined nursing educational content for cancer care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- * Ince, S.; Çevik, K. The effect of music listening on the anxiety of nursing students during their first blood draw experience. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 52, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsella Frost, C. Art in debrief: A small-scale three-step narrative inquiry into the use of art to facilitate emotional debriefing for undergraduate nurses. J. Res. Nurs. 2019, 24, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, J.; Jackson, L.; Hardman, C. A fresh perspective on medical education: The lens of the arts. Med. Educ. 2015, 49, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, M.; Eacott, B.; Willson, S. Arts-based interventions in healthcare education. Med. Humanit. 2017, 44, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byma, E.A.; Lycette, L. An integrative review of humanities-based activities in baccalaureate nursing education. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 70, 103677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, M. The meaning of Visual Thinking Strategies for nursing students. Humanities 2015, 4, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikström, B.-M. Works of art as a pedagogical tool: An alternative approach to education. Creative Nurs. 2011, 17, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arveklev, S.H.; Wigert, H.; Berg, L.; Burton, B.; Lepp, M. The use and application of drama in nursing education: An integrative review of the literature. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, e12–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jefferies, D.; Glew, P.; Karhani, Z.; McNally, S.; Ramjan, L.M. The educational benefits of drama in nursing education: A critical literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 98, 104669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.P. Poetry as an aesthetic expression for nursing: A review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 40, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raingruber, B. Assigning poetry reading as a way of introducing students to qualitative data analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 1753–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uligraff, D.K. Utilizing poetry to enhance student nurses’ reflective skills: A literature review. Belitung Nurs. J. 2019, 5, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timpani, S.; Sweet, L.; Sivertsen, N. Storytelling: One arts-based learning strategy to reflect on clinical placement: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 52, 103005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Kang, J.; De Gagne, J.C. Learning concepts of cinenurducation: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2012, 32, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; De Gagné, J.C.; Kang, J. A review of teaching-learning strategies to be used with film for prelicensure students. J. Nurs. Educ. 2013, 52, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, B.; Stasewitsch, E.; Prümper, J. Mind the gap: Workshop satisfaction and skills development in art-based learning. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2022, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Slota, M.; McLaughlin, M.; Vittone, S.; Crowell, N. Visual intelligence education using an art-based intervention: Outcomes evaluation with nursing graduate students. J. Prof. Nurs. 2022, 41, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turton, B.M.; Williams, S.; Burton, C.R.; Williams, L. Arts-based palliative care training, education and staff development: A scoping review. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfler, M.; Vasylyeva, T. Studienbewertung in systematischen Reviews der Bildungsforschung: Planungsschritte und Kriterien zur Prüfung der internen Validität von Interventionsstudien [Study evaluation in systematic reviews of educational research: Planning steps and criteria for testing the internal validity of intervention studies]. Z. Erzieh. 2023, 26, 1029–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B.G.; Smith, G.J.; Tankersley, M. Evidence-based practices in education. In APA Educational Psychology Handbook; Harris, K.R., Graham, S., Urdan, T., McCormick, C.B., Sinatra, G.M., Sweller, J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 495–527. [Google Scholar]