Emergency First Responders’ Misconceptions about Suicide: A Descriptive Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Settings

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Consideration

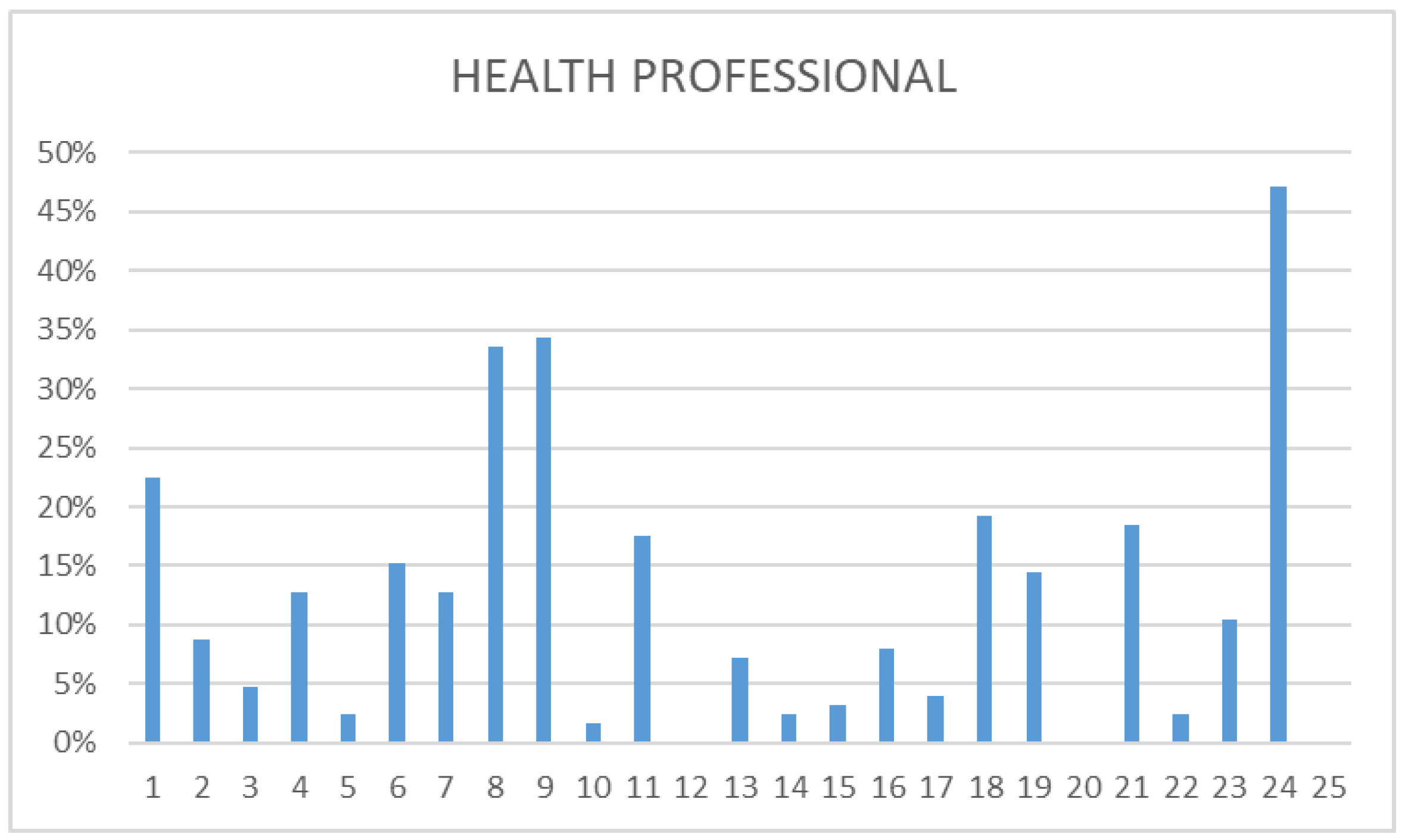

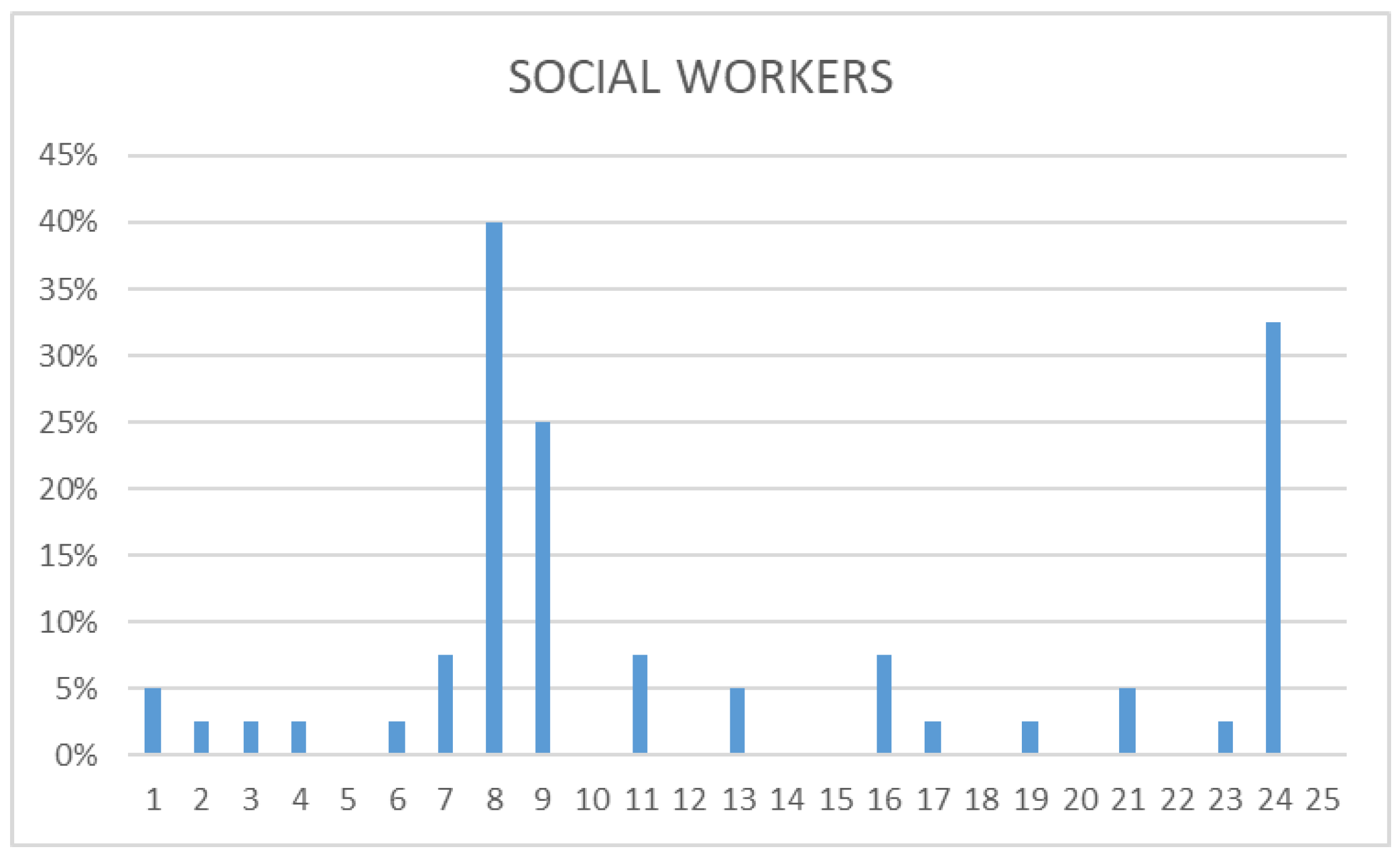

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acinas Acinas, M.P.; Muñoz Prieto, F.A. Psicología y Emergencia, 2nd ed.; Biblioteca de Psicología, Desclée de Brouwer: Bilbao, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, M. Comportamiento Suicida. Reflexiones Críticas Para su Estudio Desde un Sistema Psicológico, 1st ed.; Qartuppi: Hermosillo, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Giner, J.; Medina, A.; Giner, L. Suicidio En el Siglo XXI. Tratamiento, Manejo Clínico e Investigaciones Futuras; Enfoque Editorial S.C.: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barrigón, M.L.; Baca-García, E. Retos actuales en la investigación en suicidio. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2018, 11, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatorio del Suicidio en España 2021. Prevención del Suicidio. Available online: https://www.fsme.es/observatorio-del-suicidio-2021/ (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Observatorio del Suicidio en España 2022. Prevención del Suicidio. Available online: https://www.fsme.es/observatorio-del-suicidio-2022/ (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Suicide Rates. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/suicide-rates/indicator/english_a82f3459-en (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Sun, F.-K.; Long, A.; Boore, J. The attitudes of casualty nurses in Taiwan to patients who have attempted suicide. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuorilehto, M.S.; Melartin, T.K.; Isometsä, E.T. Suicidal behaviour among primary-care patients with depressive disorders. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domino, G.; Moore, D.; Westlake, L.; Gibson, L. Attitudes toward suicide: A factor analytic approach. J. Clin. Psychol. 1982, 38, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAllister, M.; Creedy, D.; Moyle, W.; Farrugia, C. Nurses’ attitudes towards clients who self-harm. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 40, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuku, S. Self-harm presentations in emergency departments: Staff attitudes and triage. Br. J. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1468–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebhinani, N.; Chahal, S.; Jagtiani, A.; Nebhinani, M.; Gupta, R. Medical students′ attitude toward suicide attempters. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2016, 25, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Barrero, S.A. Los mitos sobre el suicidio. La importancia de conocerlos. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2005, 34, 386–394. [Google Scholar]

- Rocamora, A. Intervención En Crisis En las Conductas Suicidas, 2nd ed.; Biblioteca de Psicología, Desclée de Brouwer: Bilbao, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- López-Martínez, L.F.; Carretero García, E.M. Guía Práctica de Prevención de la Autolesión y El Suicidio En Entorno Digitales, 1st ed.; Libertas España: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Villar Cabeza, F. Morir Antes del Suicidio, 1st ed.; Herder: Barcelona, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pacientes, I.P.; Allegados, F. La Conducta Suicida. Available online: https://consaludmental.org/publicaciones/Laconductasuicida.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- American Psychological Association. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (2002, amended Effective 1 June 2010, and 1 January 2017). Available online: https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/ (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Duncan, E.A.S.; Best, C.; Dougall, N.; Skar, S.; Evans, J.; Corfield, A.R.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Goldie, I.; Maxwell, M.; Snooks, H.; et al. Epidemiology of emergency ambulance service calls related to mental health problems and self-harm: A national record linkage study. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2019, 27, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.; Thompson, L.; McClelland, G. Hangings attended by emergency medical services: A scoping review. Br. Paramed. J. 2021, 5, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, O.; Al-haboubi, Y. Caring for the carers: We need to talk about tackling staff suicide. BMJ 2022, 379, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.C.; Wetherall, K.; Cleare, S.; Eschle, S.; Drummond, J.; Ferguson, E.; O’Connor, D.B.; O’Carroll, R.E. Suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm: National prevalence study of young adults. BJPsych Open 2018, 4, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative. 2016. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/131056/9789241564779_eng.pdf;jsessionid=DF38B26CE3575BA0BA81482889FA0CF6?sequence=1 (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Ramon, S. Attitudes of doctors and nurses to self-poisoning patients. Soc. Sci. Med. Part A Med. Psychol. Med. Sociol. 1980, 14, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramluggun, P.; Freeman-May, A.; Barody, G.; Groom, N.; Townsend, C. Changing paramedic students’ perception of people who self-harm. J. Paramed. Pract. 2020, 12, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Halabí, S.; Fonseca, E. Manual de Psicología de la Conducta Suicida, 1st ed.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Murcia Salud. Available online: https://www.murciasalud.es/pagina.php?id=306195&idsec=5574# (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Libet, B. La iniciativa cerebral inconsciente y el papel de la voluntad consciente en la acción voluntaria. Ciencias Comport. Cerebro. 1985, 8, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, C.S.; Brass, M.; Heinze, H.J.; Haynes, J.D. Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2008, 11, 543–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, E.C.; Neagle, G.; Cameron, B.; Moneypenny, M. It’s okay to talk: Suicide awareness simulation. Clin. Teach. 2019, 16, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, J.W.; Simon, R.; Rivard, P.; Dufresne, R.L.; Raemer, D.B. Debriefing with good judgment: Combining rigorous feedback with genuine inquiry. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2007, 25, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Agea, J.L.; Leal, C.; García, J.A.; Hernández, E.; Adánez, M.G.; Sáez, A. Self-learning methodology in simulated environments (MAES©): Elements and characteristics. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2016, 12, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenzi, G.; Reuben, A.D.; Diaz Agea, J.L.; Ruipérez, T.H.; Costa, C.L. Self-learning methodology in simulated environments (MAES©) utilized in hospital settings. Action-research in an Emergency Department in the United Kingdom. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2022, 61, 101–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Méndez, J.A.; Díaz Agea, J.L.; Leal Costa, C.; Jiménez Rodríguez, D.; Rojo Rojo, A.; Fenzi, G. Simulación clínica 3.0. El futuro de la simulación: El factor grupal. Rev. Latinoam. Simulación Clínica 2022, 4, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Voluntary participation | Failure to complete the questionnaire in full |

| Being in active service | Leaving during the session |

| Doctors, nurses, emergency technicians from ambulance service of Mallorca, Menorca, Ibiza | Healthcare personnel working in a hospital environment |

| Local police workers from Palma | Professionals who subsequently provide the training |

| Social workers from Mallorca | |

| Completion of the questionnaire in person |

| Myth Number | Myth |

|---|---|

| 1 | Those who want to kill themselves do not say so |

| 2 | Those who say so do not do it |

| 3 | Everyone who die by suicide are mentally ill |

| 4 | Suicide is inherited |

| 5 | The suicidal person just wants attention |

| 6 | Suicide is more common among the rich |

| 7 | Talking about suicide with a person who is at risk may encourage them to commit suicide |

| 8 | The suicidal person wants to die |

| 9 | The suicidal person is determined to die |

| 10 | The suicide attempter is a coward |

| 11 | Suicide is a normal reaction to negative experiences |

| 12 | Only old people commit suicide |

| 13 | Suicide is impulsive |

| 14 | If a suicidal person is challenged, he does not attempt it |

| 15 | Interviewing family members is a breach of confidentiality |

| 16 | A suicide attempter is a brave man |

| 17 | The media cannot contribute to suicide prevention |

| 18 | Suicide is more common among the poor |

| 19 | Once suicidal, one is never suicidal again |

| 20 | A person who recovers from a suicidal crisis is in no danger of relapse |

| 21 | Most suicides happen suddenly and without warning |

| 22 | Only psychiatric professionals can prevent suicide |

| 23 | People displaying suicidal behavior are dangerous |

| 24 | There are serious and less serious problems |

| 25 | Suicide is a crime |

| Category | Definition | Miths |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude | Belief related to some attitude of the patient displaying suicidal behaviors. | 1; 8; 9; 13 |

| Behavior | Belief related to the behavior of/to the patient displaying suicidal behaviors or his/her family members. | 2; 7; 14; 15 |

| Trait | Myths related to traits of the patient displaying suicidal behaviors. Belief related to some personal trait of the patient. | 3; 6; 10; 12; 16; 18; 19; 20; 23 |

| Environment | Myths related to the environment of the patient displaying suicidal behaviors. Belief related to some aspect of their environment. | 4; 5; 17; 22; 24 |

| Act | Myths related to the act of suicidal behavior. Belief related to the act itself. | 11; 21; 25 |

| Myth Number | True | False | Not Answered | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| 1 | 214 | 39.41% | 325 | 59.86% | 4 | 0.73% |

| 2 | 137 | 25.23% | 402 | 74.04% | 4 | 0.73% |

| 3 | 49 | 9.02% | 492 | 90.62% | 2 | 0.36% |

| 4 | 35 | 6.44% | 507 | 93.38% | 1 | 0.18% |

| 5 | 30 | 5.66% | 512 | 94.16% | 1 | 0.18% |

| 6 | 45 | 8.28% | 494 | 90.99% | 4 | 0.73% |

| 7 | 117 | 21.54% | 423 | 77.91% | 3 | 0.55% |

| 8 | 231 | 42.54% | 305 | 56.15% | 7 | 1.31% |

| 9 | 224 | 41.25% | 311 | 57.28% | 8 | 1.47% |

| 10 | 22 | 4.05% | 519 | 95.59% | 2 | 0.36% |

| 11 | 98 | 18.04% | 441 | 81.23% | 4 | 0.73% |

| 12 | 0 | 0% | 543 | 100% | 0 | 0% |

| 13 | 94 | 17.31% | 442 | 81.38% | 7 | 1.31% |

| 14 | 18 | 3.31% | 524 | 96.51% | 1 | 0.18% |

| 15 | 16 | 2.94% | 515 | 94.86% | 12 | 2.20% |

| 16 | 45 | 8.28% | 486 | 89.52% | 12 | 2.20% |

| 17 | 41 | 7.55% | 497 | 91.53% | 5 | 0.92% |

| 18 | 69 | 12.83% | 469 | 86.25% | 5 | 0.92% |

| 19 | 61 | 11.20% | 474 | 87.33% | 8 | 1.47% |

| 20 | 12 | 2.20% | 530 | 97.62% | 1 | 0.18% |

| 21 | 128 | 23.57% | 406 | 74.78% | 9 | 1.65% |

| 22 | 32 | 5.89% | 507 | 93.38% | 4 | 0.73% |

| 23 | 92 | 16.94% | 448 | 82.51% | 3 | 0.55% |

| 24 | 308 | 56.72% | 230 | 42.36% | 5 | 0.92% |

| 25 | 48 | 8.75% | 485 | 89.28% | 10 | 1.97% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ayala Romera, E.V.; Sánchez Santos, R.M.; Fenzi, G.; García Méndez, J.A.; Díaz Agea, J.L. Emergency First Responders’ Misconceptions about Suicide: A Descriptive Study. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 777-787. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020060

Ayala Romera EV, Sánchez Santos RM, Fenzi G, García Méndez JA, Díaz Agea JL. Emergency First Responders’ Misconceptions about Suicide: A Descriptive Study. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(2):777-787. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020060

Chicago/Turabian StyleAyala Romera, Elena Victoria, Rosa María Sánchez Santos, Giulio Fenzi, Juan Antonio García Méndez, and Jose Luis Díaz Agea. 2024. "Emergency First Responders’ Misconceptions about Suicide: A Descriptive Study" Nursing Reports 14, no. 2: 777-787. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020060

APA StyleAyala Romera, E. V., Sánchez Santos, R. M., Fenzi, G., García Méndez, J. A., & Díaz Agea, J. L. (2024). Emergency First Responders’ Misconceptions about Suicide: A Descriptive Study. Nursing Reports, 14(2), 777-787. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020060