Strengths Model-Based Nursing Interventions for Inpatients in Psychiatric Inpatient Settings Using a Seclusion Room: A Case Series Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Education for Nurses about the Strengths-Based Model

2.4. Implementation of Strengths Model-Based Nursing Interventions

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Demographic Information (Table 1)

| Case | Gender | Diagnosis | Length of Hospitalization at the Start of the Study | Number of Instances of Seclusion in the Past Year | Total Number of Days of Seclusion in the Past Year | Reason for Seclusion | Chlorpromazine Equivalency Values (mg) before Intervention | Chlorpromazine Equivalency Values (mg) after Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Male | Schizophrenia | 16 years and 3 months | 1 | 206 | Agitation, restlessness | 1257 | 1257 |

| B | Male | Schizophrenia | 11 years and 2 months | 1 | 177 | Violence towards other patients, agitation, restlessness, self-harm | 905 | 1205 |

| C | Female | Schizophrenia | 36 years | 6 | 145 | Agitation, restlessness, violence towards others, nuisance to other patients | 159 | 23 |

| D | Female | Intellectual disability | 4 years and 4 months | 4 | 81 | Agitation, restlessness, nuisance to other patients | 0 | 41 |

| E | Female | Schizophrenia | 32 years and 7 months | 1 | 350 | Agitation, restlessness, water intoxication | 988 | 988 |

| F | Male | Schizophrenia, intellectual disability | 31 years and 9 months | 5 | 119 | Agitation, restlessness, nuisance to others | 400 | 215 |

| G | Female | Autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability | 2 years and 3 months | 6 | 112 | Self-harm, suicide attempt | 587 | 400 |

| H | Female | Schizophrenia, anorexia nervosa | 3 years and 9 months | 1 | 365 | Violence towards others, nuisance to others | 94 | 185 |

3.2. Changes in Seclusion Days, Seclusion Time, and Open Observation Time before and after the Nursing Intervention Based on the Strengths Model (Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4)

| Case | Intervention Period (Days) | Before Intervention | After Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 220 | 0 | 22 |

| B | 177 | 0 | 103 |

| C | 232 | 97 | 152 |

| D | 238 | 157 | 0 |

| E | 196 | 0 | 55 |

| F | 171 | 41 | 25 |

| G | 171 | 58 | 3 |

| H | 171 | 0 | 10 |

| Case | Before Intervention | After Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Seclusion Time | Ratio | Total Seclusion Time | Ratio | |

| A | 3634 | 68.8 | 3082 | 58.4 |

| B | 3488 | 82.1 | 1577 | 37.1 |

| C | 2149 | 58.5 | 886 | 24.1 |

| D | 1585 | 27.7 | 3502 | 61.3 |

| E | 3654 | 77.7 | 2364 | 50.3 |

| F | 2311 | 56.3 | 2484 | 60.5 |

| G | 2514 | 61.3 | 3455 | 84.2 |

| H | 3297 | 80.3 | 2473 | 60.3 |

| Case | Before Intervention | After Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| A | 7.5 | 8.4 |

| B | 4.3 | 2.7 |

| C | 5.1 | 6.1 |

| D | 4.4 | 9.3 |

| E | 5.4 | 7.3 |

| F | 8.2 | 7.0 |

| G | 1.6 | 3.4 |

| H | 4.7 | 8.6 |

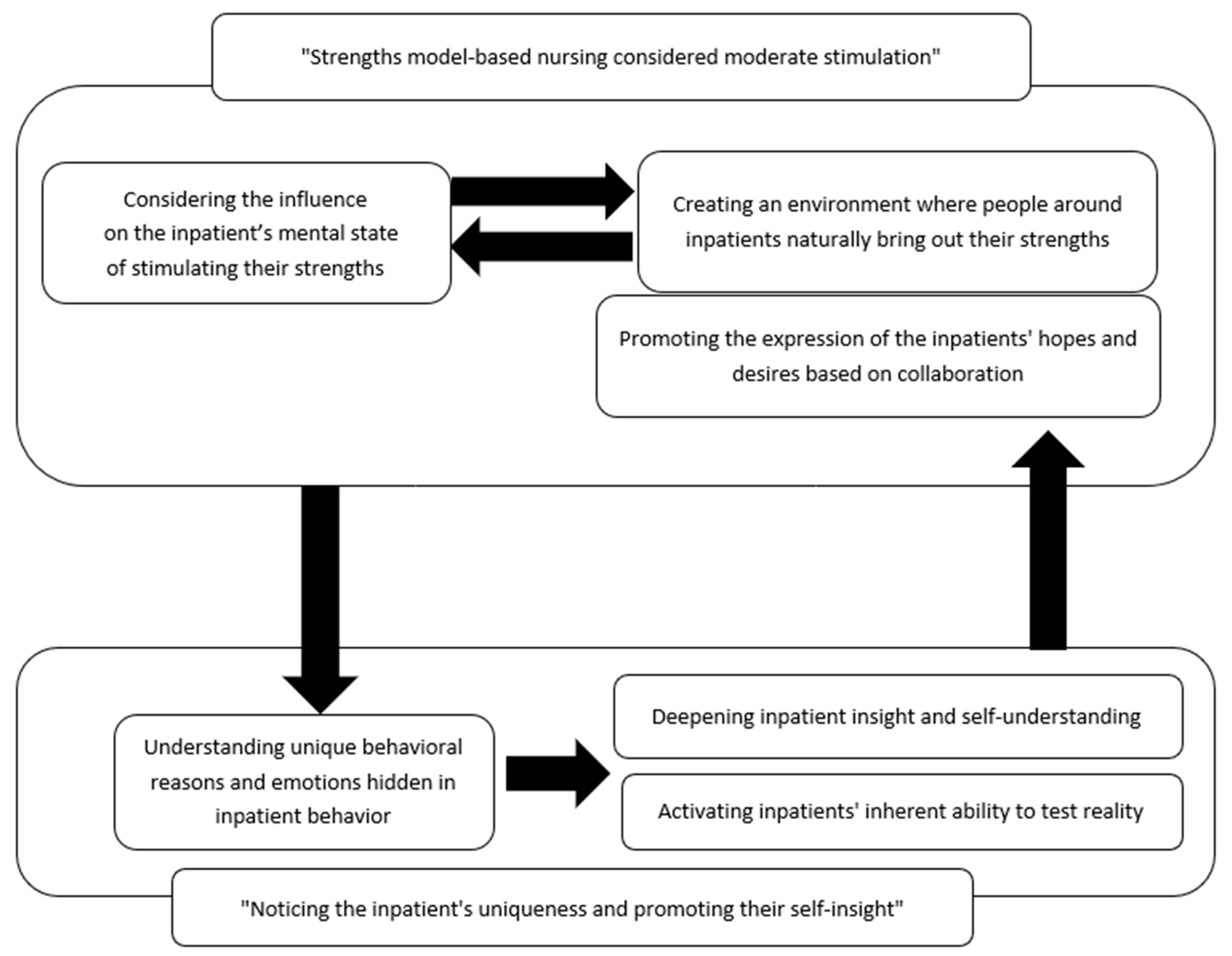

3.3. Nursing Model for Minimizing Coercive Measures Utilizing Strengths of Inpatients in the Seclusion Room (Figure 1)

| Case | Strengths of Inpatients | Nursing Interventions Based on Strengths | Inpatient Response and Influence on Seclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| A |

|

|

|

| B |

|

|

|

| C |

|

|

|

| D |

|

|

|

| E |

|

|

|

| F |

|

|

|

| G |

|

|

|

| H |

|

|

|

3.4. Subcategories of “Strengths-Model-Based Nursing Considered Moderate Stimulation”

3.4.1. Considering the Influence on the Inpatients’ Mental State of Stimulating Their Strengths

3.4.2. Creating an Environment in Which People around Inpatients Naturally Bring Out Their Strengths

3.4.3. Promoting the Expression of the Inpatients’ Hopes and Desires through Collaboration

3.5. Subcategories of “Noticing the Inpatient’s Uniqueness and Promoting the Inpatient’s Self-Insight”

3.5.1. Understanding the Unique Behavioral Causes and Emotions Underlying Inpatient Behavior

3.5.2. Deepening Inpatient Insight and Self-Understanding

3.5.3. Activating the Inpatients’ Inherent Ability to Test Reality

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Noda, T.; Sugiyama, N.; Sato, M.; Ito, H.; Sailas, E.; Putkonen, H.; Kontio, R.; Joffe, G. Influence of patient characteristics on duration of seclusion/restrain in acute psychiatric settings in Japan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 67, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinert, T.; Lepping, P.; Bernhardsgrütter, R.; Conca, A.; Hatling, T.; Janssen, W.; Keski-Valkama, A.; Mayoral, F.; Whittington, R. Incidence of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric hospitals: A literature review and survey of international trends. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2010, 45, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukasawa, M.; Miyake, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Fukuda, Y.; Yamanouchi, Y. Relationship between the use of seclusion and mechanical restraint and the nurse-bed ratio in psychiatric wards in Japan. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2018, 60, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, Y.; Hasegawa, M. Nursing care process for releasing psychiatric inpatients from long-term seclusion in Japan: Modified grounded theory approach. Nurs. Health Sci. 2014, 16, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perers, C.; Bäckström, B.; Johansson, B.A.; Rask, O. Methods and Strategies for Reducing Seclusion and Restraint in Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatient Care. Psychiatr. Q. 2022, 93, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azeem, M.W.; Aujla, A.; Rammerth, M.; Binsfeld, G.; Jones, R.B. Effectiveness of Six Core Strategies Based on Trauma Informed Care in Reducing Seclusions and Restraints at a Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Hospital. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2011, 24, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huckshorn, K.A. Policy and Procedure on Debriefing for Seclusion and Restraint. In Six Core Strategies for Reducing Seclusion and Restraint Use©; National Technical Assistance Center: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wisdom, J.P.; Wenger, D.; Robertson, D.; Van Bramer, J.; Sederer, L.I. The New York State Office of Mental Health Positive Alternatives to Restraint and Seclusion (PARS) Project. Psychiatr. Serv. 2015, 66, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, L. Safewards: A new model of conflict and containment on psychiatric wards. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, L.; James, K.; Quirk, A.; Simpson, A.; Stewart, D.; Hodsoll, J. Reducing conflict and containment rates on acute psychiatric wards: The Safewards cluster randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 1412–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallman, I.S.; O’Connor, N.; Hasenau, S.; Brady, S. Improving the Culture of Safety on a High-Acuity Inpatient Child/Adolescent Psychiatric Unit by Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Training of Staff. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2014, 27, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sams, D.P.; Garrison, D.; Bartlett, J. Innovative Strength-Based Care in Child and Adolescent Inpatient Psychiatry. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2016, 29, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapp, C.A.; Goscha, R.J. The Strengths Model: A Recovery-Oriented Approach to Mental Health Services, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 93–130. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, E.M.; Walsh, A.K.; Oldham, M.S.; Rapp, C.A. Strengths-Based Case Management: Implementation with High-Risk Youth. Fam. Soc. J. Contemp. Soc. Serv. 2007, 88, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrbova, K.; Prasko, J.; Holubová, M.; Slepecky, M.; Ocisková, M. Positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia and their relation to depression, anxiety, hope, self-stigma and personality traits—A cross-sectional study. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2018, 39, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, T.; Antonova, L. Cognitive function in schizophrenia: Deficits, functional consequences, and future treatment. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2003, 26, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson-Tops, A.; Hansson, L. Quantitative and Qualitative Aspects of the Social Network in Schizophrenic Patients Living in the Community. Relationship to Sociodemographic Characteristics and Clinical Factors and Subjective Quality of Life. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2001, 47, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbidge, C.; Oliver, C.; Moss, J.; Arron, K.; Berg, K.; Furniss, F.; Hill, L.; Trusler, K.; Woodcock, K. The association between repetitive behaviours, impulsivity and hyperactivity in people with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2010, 54, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Steen, T.A.; Seligman, M.E. Positive Psychology in Clinical Practice. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 629–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windell, D.; Norman, R.M.G. A qualitative analysis of influences on recovery following a first episode of psychosis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2013, 59, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Bendall, S.; Koval, P.; Rice, S.; Cagliarini, D.; Valentine, L.; D’Alfonso, S.; Miles, C.; Russon, P.; Penn, D.L.; et al. HORYZONS trial: Protocol for a randomised controlled trial of a moderated online social therapy to maintain treatment effects from first-episode psychosis services. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Bendall, S.; Lederman, R.; Wadley, G.; Chinnery, G.; Vargas, S.; Larkin, M.; Killackey, E.; McGorry, P.; Gleeson, J.F. On the HORYZON: Moderated online social therapy for long-term recovery in first episode psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2013, 143, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, T.; Ostermann, R.F. Strength-based assessment in clinical practice. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 65, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanley, E.; Jubb, M.; Latter, P. Partnership in Coping: An Australian system of mental health nursing. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2003, 10, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nagayama, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Oe, M. Strengths Model-Based Nursing Interventions for Inpatients in Psychiatric Inpatient Settings Using a Seclusion Room: A Case Series Study. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 644-658. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13020057

Nagayama Y, Tanaka K, Oe M. Strengths Model-Based Nursing Interventions for Inpatients in Psychiatric Inpatient Settings Using a Seclusion Room: A Case Series Study. Nursing Reports. 2023; 13(2):644-658. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13020057

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagayama, Yutaka, Koji Tanaka, and Masato Oe. 2023. "Strengths Model-Based Nursing Interventions for Inpatients in Psychiatric Inpatient Settings Using a Seclusion Room: A Case Series Study" Nursing Reports 13, no. 2: 644-658. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13020057

APA StyleNagayama, Y., Tanaka, K., & Oe, M. (2023). Strengths Model-Based Nursing Interventions for Inpatients in Psychiatric Inpatient Settings Using a Seclusion Room: A Case Series Study. Nursing Reports, 13(2), 644-658. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13020057