Abstract

During a pandemic, people are fearful of becoming infected with the virus, which causes anxiety, loss of purpose, and depression. This study aimed to evaluate the social and psychological impact, as well as the impact on homecare, of patients with hemoglobinopathies during the pandemic. Material and Methods: In total, 130 patients from four Thalassemia and Sickle Cell Disease Units of the National Health System of Greece Hospitals were examined via an anonymous questionnaire developed and distributed through stratified sampling. Results: Transfusion-dependent thalassemia, transfused sickle cell disease, and other hemoglobinopathies were represented by 130 patients. During the pandemic, the main concern of patients was the affordability of blood for transfusion. During the lockdown, patients’ moods varied, and their daily lives were disrupted by a lack of access to basic goods and communication with friends and family. Their eating habits, access to exercise, and, to a lesser extent, their financial situation have all been affected in their daily lives. It is crucial to highlight that while access to health services did not suffer in terms of medication and regular visits for their actual disease, it did suffer in terms of the systematic monitoring of complications.

1. Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic of 2019 (COVID-19), which caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), changed the world in a matter of a few weeks. Initially, it was thought that the epidemic would be severely restricted to China, but the virus spread at an alarming rate, and the pandemic spread quickly, and in March 2020, the Greek government imposed a national blockade, restricting the free movement of people and terminating all activities deemed unnecessary for about 4 months. Quarantine and national lock-ins are necessary public health measures to limit the spread of infectious diseases, but the deprivation of human freedom has negative psychological consequences. Furthermore, many people have been isolated, and some have experienced financial difficulties as a result of the economic crisis. COVID-19 has already had a significant impact on human communities all over the world, and there are concerns that people with chronic illnesses are more susceptible to serious psychological effects. Psychological consequences such as anxiety, sadness, depression, suicide, and anger have been evaluated in different people and populations of individuals to differing degrees in the published research on the effects of pandemics and quarantine to date [1].

Patients with hemoglobinopathies depend greatly on frequent hospital visits not only for transfusions but also for the evaluation and treatment of systemic complications of their disease.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, management practices and guidelines for patients with hemoglobin disorders have been established [2].

The purpose of this study was to describe the psychological effects, primarily on personal care, of patients with hemoglobinopathies, a vulnerable group in the community.

2. Material and Methods

An anonymous questionnaire was developed based on the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) [3,4] and COVID-19 Attitudes and Behaviors Scale (ACAB) [5] distributed through stratified sampling to 130 patients from four Thalassemia and Sickle Cell Diseases units of the National Hospital System. The questionnaire mostly consisted of two multiple-choice sections. The first section addressed basic demographic information (age, gender, marriage status/relationship status, and place of residence), potential stressors (self-quarantine/isolation period, living conditions, and special employment/study status), and coping mechanisms (exercise frequency, number of expenses, interaction and influence of friends, family, and pets). The second component consisted of four thematic divisions that were assessed via a brief questionnaire: their concerns and anxieties, the field of awareness, and the field of everyday influence.

The MedCalc 2018 program was used to perform statistical analysis on the questionnaires. The hypothesis test was performed at a significance level of 5%. Parametric and non-parametric controls were used depending on the regularity of variables and the amount of data. The control was performed using the Shapiro–Wilk test.

The data’s reliability was assessed for each research element using Cronbach Alpha as a factor that calculates internal reliability consistency. There was higher reliability since the rates were greater than 0.9.

Limitation of statistical analysis: not all questions were answered by the participants.

3. Results

There were 130 adult participants, with 66 (51%) women, 64 (49%) men, 109 with transfusion-dependent thalassemia (84%), 20 with transfused sickle cell disease (15%), and 1other (1%). During the epidemic, the major concern of patients was the lack of blood for transfusion 50 (64%).

During the lockdown, 58(45%) patients said that it had a significant impact on their general emotional state, 57 (42%) reported that it had a mild impact, and 15 (13%) reported that it had no effect at all.

Analytically, the emotions they experienced and that persisted the longest were a concern for their health in 16 individuals (21%) and 9 were familiar (12%) while 3 (3%) did not stress at all.

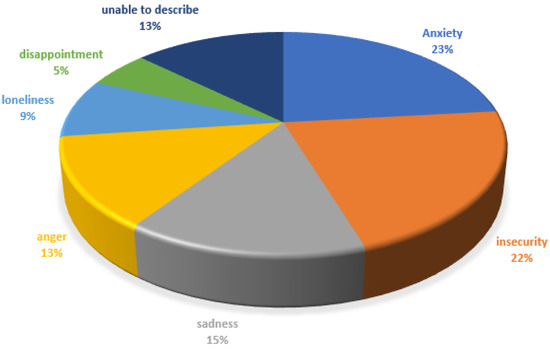

Anxiety 18 (23%), insecurity 17 (22%), sadness 12 (15%), anger 10 (13%), loneliness 7 (9%), and disappointment 4 (5%) were the emotions experienced by patients with mood disorders 2 to 3 times per week, whereas 10 could (13%) not describe their reactions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Feelings experienced by patients 2 to 3 times per week.

In the present analysis, there is no statistically significant difference between the emotions experienced by female and male patients, even though women are thought to be more emotionally susceptible.

Communication with family and friends 51 (66%) and exercise had the greatest impact on daily living 24 (28%).

The lack of access to stores and the market as a necessary consequence of the lockdown primarily affected the clothing market 27 (35.4%) and, to a lesser extent, the markets for food 15 (19.7%) and electronic appliances 12 (15%). Notably, 23 (29.9%) were unlikely to be affected because they were familiar with using the internet to purchase various products. The patients’ economic status was influenced to a lower extent (52.0%), but it had a disproportionate impact on 10 (13%) of the market shutdown, which resulted in the loss of their employment. A considerable number of eating habits did not change at all as a result of cooking at home 46 (59.7%), yet 29 (36.9%) modified their habits excessively by eating more or using prepared foods.

Most endocrinologists recommend walking or swimming to avoid osteoporosis. Mild exercise is beneficial for maintaining a good cardiovascular status in patients with hemoglobinopathies.

Despite the restrictions, many people (36 (47%) continued to participate in physical activity, while 28 (36.9%) stopped all activities for the fear of being exposed to the virus.

During the lockdown, the consistency of scheduled transfusions was not affected 56 (71.8%), although they were occasionally delayed (17 (21.3%)) or did not show up at all (6 (6.9%)). Similarly, when it came to systemic iron chelation therapy, 63 (81.8%) were consistent, whereas 5 (6.1%) ceased taking the medication regularly due to a fear of running out.

The pandemic and lockdown had an impact on the annual follow-up of basic disease comorbidities, with 32 (41.6%) postponing the standard cardiac evaluation, 23 (30.1%) postponing magnetic resonance imaging of the liver-heart, and 23 (23%) cancelling major assessments or treatments such as biopsies or in vitro fertilization (IVF) therapeutic interventions. Finally, four (5.3%) of scheduled surgeries were rescheduled (Table 1 provides a detailed presentation of data).

Table 1.

Detailed data about the variables affected by the pandemic.

4. Discussion

COVID-19, a new illness caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [6], has spread throughout the planet in a couple of months, urging the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare it as a pandemic. COVID-19 has induced significant pressure on healthcare systems due to its high direct fatality for such a contagious disease [7]. The rapid consumption of inpatient medicine, quarantine, and critical care services are examples of direct impacts. Inadvertently, public health interventions such as social distancing, shelter-in-place regulations, and personal protective equipment (PPE) standards have generated additional concerns for both health care providers and patients. Isolation and quarantine are two of several tools used by public health professionals to treat infectious diseases [8]. Both are designed to keep people from interacting with infected or potentially infected people. These measures can be used to prevent or mitigate the consequences of outbreaks of infectious diseases. Their priority is to keep a highly contagious infection from spreading [9].

Blood sufficiency for transfusions was extremely crucial for patients 50 (64%) in our study because there was a fear of blood donors heading to health care facilities to donate blood, and substantive deficiencies were noted [10].

A major concern and challenge for the mental health of patients with hemoglobinopathy in our societies was the risk for worsening of pre-existing emotional disorders, such as depression or anxiety, as a consequence of expectations or the need to isolate themselves. Crucial to the daily support of patients with hemoglobinopathies is their relatives, as well as their friends, acquaintances, and supporters with whom they share common problems [11,12].

The threat of losing loved ones and the presence and fear of the worsening of a chronic illness were the causal factors for the onset of post-traumatic stress disorder in areas significantly affected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus’s health crisis. Anxiety (23%), insecurity (2%), sadness (15%), anger (13%), loneliness (9%), and disappointment (5%) were the emotions experienced by patients with hemoglobinopathies 2 to 3 times per week, while 13% were unable to describe their emotions. In light of the deadly virus, the lack of traditional farewell ceremonies and social contact with family and friends had the greatest impact on patients during quarantine (66%). Isolation, also referred to as social isolation, is a painful experience that involves, among other factors, being separated from loved ones and changing one’s daily routine [12].

Social isolation is described as an “insufficient quality and quantity of social contacts with other individuals, groups, communities, and wider levels of social environment where human interaction exists.” Social isolation has been linked to psychological issues, particularly among vulnerable groups Staying at home for long periods isolates people from the physical presence (seeing, hearing, smell, and touch) of others. Generally, in the first two weeks, there may be a reduction in stress, which may be explained by the fact that the person’s responsibilities are lessened because they are not working. Isolation, on the other hand, raises anxiety and stress over the course of a few weeks, particularly when the timeframe is undetermined [13,14].

When people are deprived of social interaction for an extended period, they become depressed.

Depression is characterized by sad emotions, a loss of hope and sense of optimism, and an inability to seek a cure [15].

Despite the restrictions, many individuals (47%) continued to exercise, while 37% discontinued all activities for fear of becoming infected with the virus. When the gym clubs closed, people who continued to exercise had the option to reconnect with others outdoors, as this was the only way to get through quarantine [16]. Many people anticipated a shortage of essentials such as food, clothes, and transportation as European countries went into lockdown. In the present study, the loss of access to stores and the marketplace as a result of the lockdown had the greatest impact on the clothing trade (36%), with the food and electronics sectors coming in second and third, 20% and 15%, respectively.

People’s inability to dine in restaurants has serious consequences for several food companies. During that period, McDonald’s sales in Europe dropped nearly 70%. The major retailers have limited their scope of operations and redefined their distribution and sales strategies [17]. Amazon grocery shop e-commerce has increased by 60% [18]. It is important to mention that 29% were unlikely to be affected because they have already used the Internet to purchase a variety of goods.

In the current study, 60% stated that they had not modified their eating habits or home cooking significantly, but a considerable number (37%) claimed they preferred prepared foods. The coronavirus outbreak has raised a demand for foods that provide immune support, such as organic products. However, a smaller population of individuals seek to calm their emotions. Anxiety, fear, and loneliness resulted in an increase in unhealthy food intake, such as pastries, cookies, and snacks, as well as an increase in alcohol use. Most researchers remain optimistic that the pandemic will result in the development of a better lifestyle [19].

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted health systems worldwide, and most countries have yet to recover from the acute consequences of increased mortality and morbidity caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Patients with hemoglobinopathies had no difference in their scheduled transfusions (71%); however, a small percentage had to reschedule their appointments, primarily due to a lack of blood (21%) [20]. Patients who did not require frequent transfusions missed appointments or did not show up at all, believing that their hospitalization, despite the measures, placed them in danger of developing an infection. There was a particular impact on treatment management and outcomes. Patients have postponed significant studies, such as MRI for quantitative measurement of liver and heart iron, annual cardiological evaluation, and scheduled surgeries or IVF treatments. Since the majority of hospitals were transformed into COVID treatment centers, patients lost access to specialist and necessary evaluations.

Nevertheless, health professionals around the world and in our country have banded together to achieve the best results possible [21,22]. They managed to cope with the tremendous difficulties of the pandemic despite having little resources and severe shortages of medical supplies as well as staff. From the social world to medicine and the nursing community, there was an exceptional outpour of sympathy and thanks, as well as an outpour of support from colleagues. Even now, the epidemic continues, despite high immunization rates in several countries.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, patients with hemoglobinopathies adhered to the same stringent measures as were adopted to reduce and manage the pandemic in the general population. Their living standards, similarly, to many people in this difficult time, were disturbed, and they experienced emotions of uncertainty, particularly for the future. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, there has been an imbalance in the provision of chronic care, with several routine prescriptions, preventive, diagnostic, treatment, and rehabilitation visits being delayed, postponed, or even cancelled. The personal anxiety associated with the threat of exposure to the virus, the isolation at home, and the recent changes in the public hospital to convert them to COVID clinics all contributed to the discontinuation of the systematic annual monitoring of patients with hemoglobinopathies. There was no difference in the reported results among hospitals in capitals and hospitals in provinces.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D. and A.X.; methodology, A.M.; S.D., K.M., T.A.; validation, K.M., E.K. and A.X.; formal analysis, K.M.; investigation, L.R.; M.D.D., L.E., C.K.; resources, S.D.; data curation, K.M., M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D.; writing—review and editing, S.D., A.X.; visualization, S.D.; supervision, T.A.; All authors participated equally in the collection and elaboration of the above work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Locally, the permission of the IRB was not considered required for the present study because it was non-invasive, anonymized, and all personal data standards were maintained.

Informed Consent Statement

Due to the use of an anonymous questionnaire that required no personally identifiable information other than basic demographics, patient consent was not requested.

Data Availability Statement

The data is archived electronically in accordance with all the principles of personal data protection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shah, S.M.A.; Mohammad, D.; Qureshi, M.F.H.; Abbas, M.Z.; Aleem, S. Prevalence, Psychological Responses and Associated Correlates of Depression, Anxiety and Stress in a Global Population, During the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 57, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taher, A.T.; Bou-Fakhredin, R.; Kreidieh, F.; Motta, I.; De Franceschi, L.; Cappellini, M.D. Care of patients with hemoglobin disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic: An overview of recommendations. Am. J. Hematol. 2020, 95, E208–E210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieven, T. Global validation of the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS). Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsipropoulou, V.; Nikopoulou, V.A.; Holeva, V.; Nasika, Z.; Diakogiannis, I.; Sakka, S.; Parlapani, E. Psychometric properties of the Greek version of FCV-19S. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict 2021, 19, 2279–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistree, D.; Loyalka, P.; Fairlie, R.; Bhuradia, A.; Angrish, M.; Lin, J.; Bayat, V. Instructional interventions for improving COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, behaviors: Evidence from a large-scale RCT in India. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 276, 113846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.C.; Shih, T.P.; Ko, W.C.; Tang, H.J.; Hsueh, P.R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Duan, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, Z.J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: How countries should build more resilient health sys-tems for preparedness and response. Glob. Health J. 2020, 4, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetron, M.; Landwirth, J. Public health and ethical considerations in planning for quarantine. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2005, 78, 329–334. [Google Scholar]

- Naguib, M.M.; Ellström, P.; Järhult, J.D.; Lundkvist, Å.; Olsen, B. Towards pandemic preparedness beyond COVID-19. Lancet Microbe 2020, 1, e185–e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanworth, S.J.; New, H.V.; O Apelseth, T.; Brunskill, S.; Cardigan, R.; Doree, C.; Germain, M.; Goldman, M.; Massey, E.; Prati, D.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on supply and use of blood for transfusion. Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e756–e764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arian, M.; Vaismoradi, M.; Badiee, Z.; Soleimani, M. Understanding the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health-related quality of life amongst Iranian patients with beta thalassemia major: A grounded theory. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavate, V. Thalassemia: With the “red” in the bag amid COVID-19 reflections. J. Patient Exp. 2020, 7, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda-Loyola, W.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, I.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Ganz, F.; Torralba, R.; Oliveira, D.V.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Impact of Social Isolation Due to COVID-19 on Health in Older People: Mental and Physical Effects and Recommendations. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharan, P.; Rajhans, P. Social and psychological consequences of “Quarantine: A systematic review and application to India. Indian J. Soc. Psych. 2020, 36, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustun, G. Determining depression and related factors in a society affected by COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 67, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Mao, L.; Nassis, G.P.; Harmer, P.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Li, F. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): The need to maintain regular physical activity while taking precautions. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M.; Li, M.; Malik, A.; Pomponi, F.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Wiedmann, T.; Faturay, F.; Fry, J.; Gallego, B.; Geschke, A.; et al. Global socio-economic losses and environmental gains from the Coronavirus pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, Suborna, Understanding Coronanomics: The Economic Implications of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3566477 (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Cinelli, G.; De Lorenzo, A. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, K.K.; Raturi, M.; Siddiqui, A.D.; Cerny, J. Because every drop counts: Blood donation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 2020, 27, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirsky, J.B.; Horn, D.M. Chronic disease management in the COVID-19 era. Am. J. Manag. Care 2020, 26, 329–330. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, S.F.; Anwar, S. Management of Hemoglobin Disorders During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Med. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).