Retrocochlear Auditory Dysfunctions (RADs) and Their Treatment: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

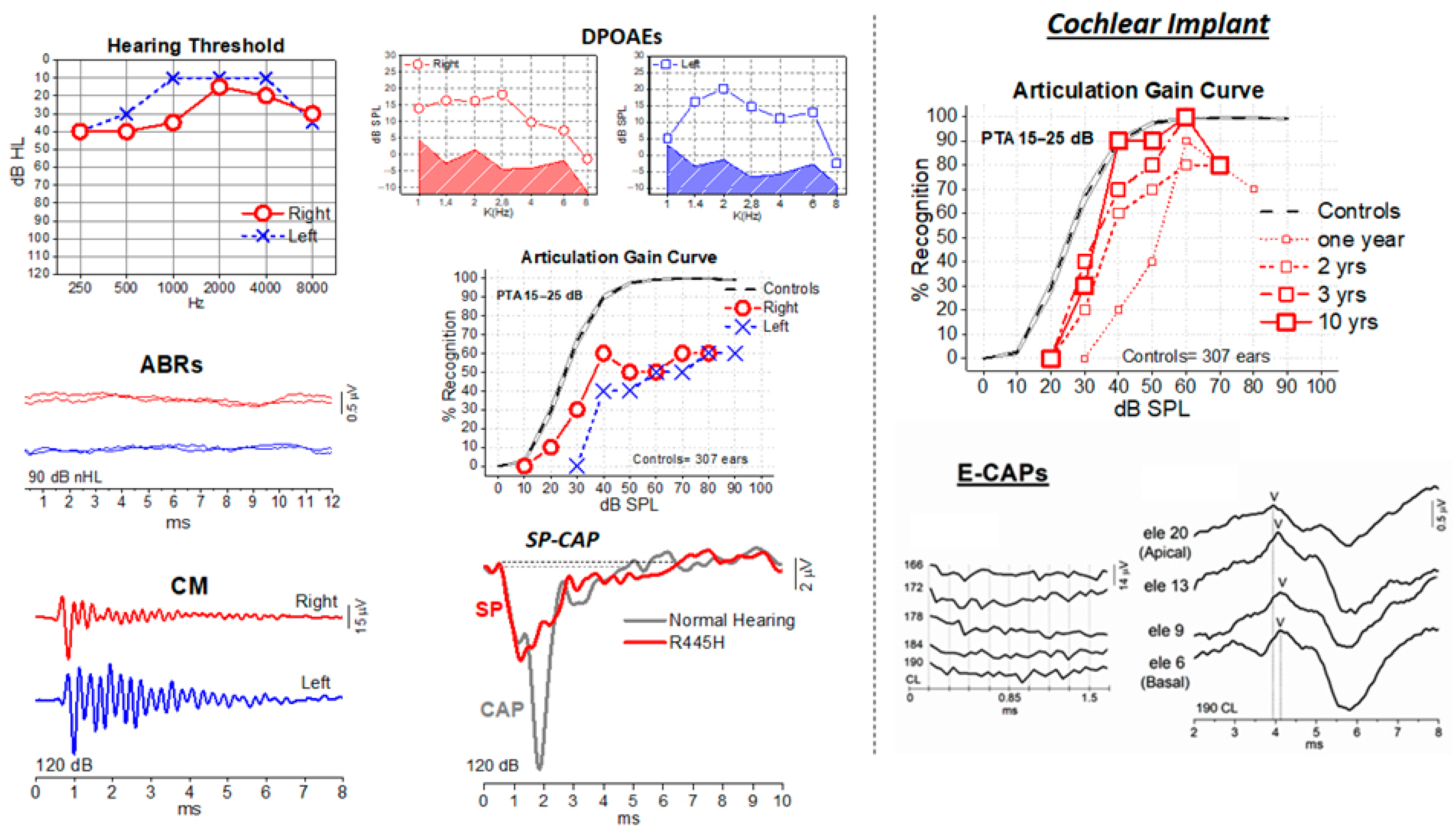

2. Auditory Neuropathies (AN)

3. Auditory Processing Disorders (APD)

4. RAD Rehabilitation

4.1. Bottom-Up Rehabilitative Approaches

4.1.1. Auditory Training in APD

4.1.2. AT and Evidence-Based Approaches

4.1.3. Hearing Aids

4.1.4. Hearing Aids in ANSD

4.1.5. Low-Gain Hearing Aids in APD

4.1.6. Over the Counter (OTC) Hearing Aids and Others Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) Devices

4.1.7. Assistive Listening Devices (ALDs)

- Personal wireless systems: A remote microphone (RM) worn by the speaker transmits sound via radiofrequency (FM) or infrared (IR) to a receiver worn by the listener, thereby bypassing background noise. This approach significantly improves speech understanding in challenging environments such as classrooms or meetings.

- Telephone amplifiers and TTY/TDD devices: These support telephone conversations by amplifying the voice or converting speech to text.

- Captioned televisions and devices: Systems that display captions for TV programs or live speech, with some devices providing real-time speech-to-text conversion.

- Bluetooth and wireless streaming: Many modern HAs and cochlear implants can stream audio directly from smartphones, televisions, or other devices, functioning as ALDs to deliver clear, amplified sound without background noise.

- Alerting devices: For safety, these devices may flash light or vibrate to signal alarms, doorbells or a baby’s cry.

4.1.8. ALD in Children with APD

4.1.9. ALD in Adults with APD

4.1.10. Cochlear Implant in AN

4.2. Top-Down Rehabilitative Approaches

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RADs | Retrocochlear Auditory Dysfunctions |

| RAD | Retrocochlear Auditory Dysfunction |

| AN | Auditory Neuropathy |

| APD | Auditory Processing Disorders |

| ANSD | Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder |

| HL | Hearing Loss |

| HHL | Hidden Hearing Loss |

| ABR | Auditory Brainstem Responses |

| OAE | Otoacoustic Emissions |

| CM | Cochlear Microphonics |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| PTA | Pure Tone Average |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CAEP | Cortical Auditory Evoked Potentials |

| IAC | Internal Auditory Canal |

| CPA | Cerebellopontine Angle |

| CI | Cochlear Implant |

| HA | Hearing Aid |

| AT | Auditory Training |

| CBAT | Computer-Based Auditory Training |

| ALD | Assistive Listening Devices |

| RM | Remote Microphone |

| RMHA | Remote Microphone Hearing Aids |

| OTC | Over The Counter |

| PSAPs | Personal Sound Amplification Products |

| FM | Frequency Modulation |

| IR | Infrared |

| CS | Compensatory Strategies |

| CMT | Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease |

| DDON | Deafness–dystonia–optic neuropathy |

| DDP1 | Deafness–dystonia peptide-1 |

| NF2 | Neurofibromatosis type 2 |

| OPA1 | Gene name |

| ROR1 | Gene name |

| ATP1A3 | Gene name |

| DIAPH3 | Gene name |

| MPZ | Gene name |

| PMP22 | Gene name |

| TIMM8A | Gene name |

| AIFM1 | Gene name |

| NARS2 | Gene name |

| TMPRSS3 | Gene name |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| ADHD | Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorders |

| ASHA | American Speech-Language-Hearing Association |

| AAA | American Academy of Audiology |

| BSA | British Society of Audiology |

| TTY | Teletypewriter |

| TDD | Telecommunication Device for the Deaf |

References

- Musiek, F.; Shinn, J.; Chermak, G.; Bamiou, D. Perspectives on the Pure-Tone Audiogram. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2017, 28, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bess, F.H. Clinical assessment of speech recognition. In Principles of Speech Audiometry; Konkle, D.F., Rintelmann, W.F., Eds.; University Park Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Starr, A.; Mc Pherson, D.; Patterson, J.; Don, M.; Luxford, W.; Shannon, R.; Sininger, Y.; Tonakawa, L.; Waring, M. Absence of both auditory evoked potentials and auditory percepts dependent on timing cues. Brain 1991, 114, 1157–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, A.; Picton, T.W.; Sininger, Y.; Hood, L.J.; Berlin, C.I. Auditory neuropathy. Brain 1996, 119, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiek, F.E.; Charette, L.; Morse, D.; Baran, J.A. Central deafness associated with a midbrain lesion. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2004, 15, 133–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). (Central) Auditory Processing Disorders; Technical Report; American Speech-Language-Hearing Association: Rockville, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, T.; Starr, A. Auditory neuropathy—Neural and synaptic mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2016, 12, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rance, G.; Starr, A. Pathophysiological mechanisms and functional hearing consequences of auditory neuropathy. Brain 2015, 138, 3141–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roux, I.; Safieddine, S.; Nouvian, R.; Grati, M.; Simmler, M.-C.; Bahloul, A.; Perfettini, I.; Le Gall, M.; Rostaing, P.; Hamard, G.; et al. Otoferlin, Defective in a Human Deafness Form, Is Essential for Exocytosis at the Auditory Ribbon Synapse. Cell 2006, 127, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangršič, T.; Lasarow, L.; Reuter, K.; Takago, H.; Schwander, M.; Riedel, D.; Frank, T.; Tarantino, L.M.; Bailey, J.S.; Strenzke, N.; et al. Hearing requires otoferlin-dependent efficient replenishment of synaptic vesicles in hair cells. Nat. Neurosci. 2010, 13, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Ballesteros, M.; del Castillo, F.J.; Martín, Y.; Moreno-Pelayo, M.A.; Morera, C.; Prieto, F.; Marco, J.; Morant, A.; Gallo-Terán, J.; Morales-Angulo, C.; et al. Auditory neuropathy in patients carrying mutations in the otoferlin gene (OTOF). Hum. Mutat. 2003, 22, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlastarakos, P.; Nikolopoulos, T.; Tavoulari, E.; Papacharalambous, G.; Korres, S. Auditory neuropathy: Endocochlear lesion or temporal processing impairment? Implications for diagnosis and management. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2008, 72, 1135–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdo, S.; Di Berardino, F.; Bruno, G. Is auditory neuropathy an appropriate term? A systematic literature review on its aetiology and pathogenesis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2021, 41, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaette, R.; McAlpine, D. Tinnitus with a normal audiogram: Physiological evidence for hidden hearing loss and computational model. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 13452–13457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, K.L.; Pinto, A.; Fischer, M.E.; Klein, B.E.; Klein, R.; Levy, S.; Tweed, T.S.; Cruickshanks, K.J. Self-Reported Hearing Difficulties Among Adults with Normal Audiograms: The Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Ear Hear. 2015, 36, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberman, M.C.; Liberman, L.D.; Maison, S.F. Efferent feedback slows cochlear aging. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 4599–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gröschel, M.; Götze, R.; Ernst, A.; Basta, D. Differential impact of temporary and permanent noise-induced hearing loss on neuronal cell density in the mouse central auditory pathway. J. Neurotrauma. 2010, 27, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Profant, O.; Škoch, A.; Balogová, Z.; Tintěra, J.; Hlinka, J.; Syka, J. Diffusion tensor imaging and MR morphometry of the central auditory pathway and auditory cortex in aging. Neuroscience 2014, 28, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.; Votruba, M.; Pesch, U.E.A.; Thiselton, D.L.; Mayer, S.; Moore, A.; Rodriguez, M.; Kellner, U.; Leo-Kottler, B.; Auburger, G.; et al. OPA1, Encoding a Dynamin-Related GTPase, Is Mutated in Autosomal Dominant Optic Atrophy Linked to Chromosome 3q28. Nat. Genet. 2000, 26, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delettre, C.; Lenaers, G.; Griffoin, J.M.; Gigarel, N.; Lorenzo, C.; Belenguer, P.; Pelloquin, L.; Grosgeorge, J.; Turc-Carel, C.; Perret, E.; et al. Nuclear Gene OPA1, Encoding a Mitochondrial Dynamin-Related Protein, Is Mutated in Dominant Optic Atrophy. Nat. Genet. 2000, 26, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bill Daniels Center for Children’s Hearing. Guidelines for Identification and Management of Infants and Young Children with Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder; The Children’s Hospital—Colorado: Aurora, CO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Santarelli, R.; Starr, A. Mutation of OPA1 Gene Causes Deafness by Affecting Function of Auditory Nerve Terminals. Brain Res. 2009, 1300, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarelli, R.; Rossi, R.; Scimemi, P.; Cama, E.; Valentino, M.L.; La Morgia, C.; Caporali, L.; Liguori, R.; Magnavita, V.; Monteleone, A.; et al. OPA1-Related Auditory Neuropathy: Site of Lesion and Outcome of Cochlear Implantation. Brain 2015, 138, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Horta, O.; Abad, C.; Sennaroglu, L.; Ii, J.F.; DeSmidt, A.; Bademci, G.; Tokgoz-Yilmaz, S.; Duman, D.; Cengiz, F.B.; Grati, M.; et al. ROR1 Is Essential for Proper Innervation of Auditory Hair Cells and Hearing in Humans and Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 5993–5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, T.H.; Lykke-Hartmann, K. Insights into the Pathology of the A3 Na+/K+-ATPase Ion Pump in Neurological Disorders; Lessons from Animal Models. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaides, P.; Appleton, R.E.; Fryer, A. Cerebellar Ataxia, Areflexia, Pes Cavus, Optic Atrophy, and Sensorineural Hearing Loss (CAPOS): A New Syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 1996, 33, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demos, M.K.; van Karnebeek, C.D.; Ross, C.J.; Adam, S.; Shen, Y.; Zhan, S.H.; Shyr, C.; Horvath, G.; Suri, M.; Fryer, A.; et al. A Novel Recurrent Mutation in ATP1A3 Causes CAPOS Syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2014, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.H.; Oh, D.Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.; Han, J.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Park, H.R.; Park, M.K.; Kim, N.K.D.; Lee, J.; et al. ATP1A3 Mutations Can Cause Progressive Auditory Neuropathy: A New Gene of Auditory Synaptopathy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, C.J.; Burmeister, M.; Lesperance, M.M. Diaphanous Homolog 3 (Diap3) Overexpression Causes Progressive Hearing Loss and Inner Hair Cell Defects in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Human Deafness. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, C.J.; Emery, S.B.; Thorne, M.C.; Ammana, H.R.; Śliwerska, E.; Arnett, J.; Hortsch, M.; Hannan, F.; Burmeister, M.; Lesperance, M.M. Increased Activity of Diaphanous Homolog 3 (DIAPH3)/Diaphanous Causes Hearing Defects in Humans with Auditory Neuropathy and in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 13396–13401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.B.; Isaacson, B.; Sivakumaran, T.A.; Starr, A.; Keats, B.J.B.; Lesperance, M.M. A Gene Responsible for Autosomal Dominant Auditory Neuropathy (AUNA1) Maps to 13q14-21. J. Med. Genet. 2004, 41, 872–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, A.; Isaacson, B.; Michalewski, H.J.; Zeng, F.G.; Kong, Y.Y.; Beale, P.; Paulson, G.W.; Keats, B.J.B.; Lesperance, M.M. A Dominantly Inherited Progressive Deafness Affecting Distal Auditory Nerve and Hair Cells. JARO J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2004, 5, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannacone, F.P.; Rahne, T.; Zanoletti, E.; Plontke, S.K. Cochlear implantation in patients with inner ear schwannomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis of audiological outcomes. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 6175–6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Gjini, E.K.; Kooper-Johnson, S.; Cooper, M.I.; Gallant, C.; Noonan, K.Y. Cochlear Implant Outcomes in Patients with Intralabyrinthine Schwannoma: A Scoping Review. Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 3910–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, A.; Dong, C.J.; Michalewski, H.J. Brain Potentials before and during Memory Scanning. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1996, 99, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhagen, W.I.M.; Huygen, P.L.M.; Gabreëls-Festen, A.A.W.M.; Engelhart, M.; Van Mierlo, P.J.W.B.; Van Engelen, B.G.M. Sensorineural Hearing Impairment in Patients with Pmp22 Duplication, Deletion, and Frameshift Mutations. Otol. Neurotol. 2005, 26, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabzińska, D.; Korwin-Piotrowska, T.; Drechsler, H.; Drac, H.; Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz, I.; Kochański, A. Late-Onset Charcot-Marie-Tooth Type 2 Disease with Hearing Impairment Associated with a Novel Pro105Thr Mutation in the MPZ Gene. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2007, 143, 2196–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rance, G.; Fava, R.; Baldock, H.; Chong, A.; Barker, E.; Corben, L.; Delatycki, M.B. Speech Perception Ability in Individuals with Friedreich Ataxia. Brain 2008, 131, 2002–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranebjaerg, L.; Schwartz, C.; Eriksen, H.; Andreasson, S.; Ponjavic, V.; Dahl, A.; E Stevenson, R.; May, M.; Arena, F.; Barker, D. A new X linked recessive deafness syndrome with blindness, dystonia, fractures, and mental deficiency is linked to Xq22. J. Med. Genet. 1995, 32, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmad, F.; Merchant, S.N.; Nadol, J.B.; Tranebjærg, L. Otopathology in Mohr-Tranebjærg Syndrome. Laryngoscope 2007, 117, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, J.T.; Kanis, A.B.; Tan, L.Y.; Tranebjærg, L.; Vore, A.; Smith, R.J.H. Cochlear Implantation in Deafness-Dystonia-Optic Neuronopathy (DDON) Syndrome. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2008, 72, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawarai, T.; Yamazaki, H.; Yamakami, K.; Tsukamoto-Miyashiro, A.; Kodama, M.; Rumore, R.; Caltagirone, C.; Nishino, I.; Orlacchio, A. A Novel AIFM1 Missense Mutation in a Japanese Patient with Ataxic Sensory Neuronopathy and Hearing Impairment. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 409, 116584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joza, N.; Pospisilik, J.A.; Hangen, E.; Hanada, T.; Modjtahedi, N.; Penninger, J.M.; Kroemer, G. AIF: Not JustANSDApoptosis-Inducing Factor. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1171, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, L.; Guan, J.; Ealy, M.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, Z.; Campbell, C.A.; Wang, F.; et al. Mutations in Apoptosis-Inducing Factor Cause X-Linked Recessive Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder. J. Med. Genet. 2015, 52, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Richard, E.M.; Wang, X.; Shahzad, M.; Huang, V.H.; Qaiser, T.A.; Potluri, P.; Mahl, S.E.; Davila, A.; Nazli, S.; et al. Mutations of Human NARS2, Encoding the Mitochondrial Asparaginyl-TRNA Synthetase, Cause Nonsyndromic Deafness and Leigh Syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Aghaie, A.; Perfettini, I.; Avan, P.; Delmaghani, S.; Petit, C. Pejvakin-Mediated Pexophagy Protects Auditory Hair Cells against Noise-Induced Damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 8010–8017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmaghani, S.; Del Castillo, F.J.; Michel, V.; Leibovici, M.; Aghaie, A.; Ron, U.; Van Laer, L.; Ben-Tal, N.; Van Camp, G.; Weil, D.; et al. Mutations in the Gene Encoding Pejvakin, a Newly Identified Protein of the Afferent Auditory Pathway, Cause DFNB59 Auditory Neuropathy. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwander, M.; Sczaniecka, A.; Grillet, N.; Bailey, J.S.; Avenarius, M.; Najmabadi, H.; Steffy, B.M.; Federe, G.C.; Lagler, E.A.; Banan, R.; et al. A Forward Genetics Screen in Mice Identifies Recessive Deafness Traits and Reveals That Pejvakin Is Essential for Outer Hair Cell Function. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 2163–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borck, G.; Rainshtein, L.; Hellman-Aharony, S.; Volk, A.; Friedrich, K.; Taub, E.; Magal, N.; Kanaan, M.; Kubisch, C.; Shohat, M.; et al. High Frequency of Autosomal-Recessive DFNB59 Hearing Loss in ANSD Isolated Arab Population in Israel. Clin. Genet. 2012, 82, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebermann, I.; Walger, M.; Scholl, H.P.N.; Issa, P.C.; Lüke, C.; Nürnberg, G.; Lang-Roth, R.; Becker, C.; Nürnberg, P.; Bolz, H.J. Truncating Mutation of the DFNB59 Gene Causes Cochlear Hearing Impairment and Central Vestibular Dysfunction. Hum. Mutat. 2007, 28, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaleshtori, M.H.; Simpson, M.A.; Farrokhi, E.; Dolati, M.; Hoghooghi Rad, L.; Geshnigani, S.A.; Crosby, A.H. Novel Mutations in the Pejvakin Gene Are Associated with Autosomal Recessive Non-Syndromic Hearing Loss in Iranian Families. Clin. Genet. 2007, 72, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin, R.W.J.; Kalay, E.; Oostrik, J.; Çaylan, R.; Wollnik, B.; Arslan, S.; Den Hollander, A.I.; Birinci, Y.; Lichtner, P.; Strom, T.M.; et al. Involvement of DFNB59 Mutations in Autosomal Recessive Nonsyndromic Hearing Impairment. Hum. Mutat. 2007, 28, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmaghani, S.; Defourny, J.; Aghaie, A.; Beurg, M.; Dulon, D.; Thelen, N.; Perfettini, I.; Zelles, T.; Aller, M.; Meyer, A.; et al. Hypervulnerability to Sound Exposure through Impaired Adaptive Proliferation of Peroxisomes. Cell 2015, 163, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guipponi, M. The Transmembrane Serine Protease (TMPRSS3) Mutated in Deafness DFNB8/10 Activates the Epithelial Sodium Channel (ENaC) in Vitro. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002, 11, 2829–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasquelle, L.; Scott, H.S.; Lenoir, M.; Wang, J.; Rebillard, G.; Gaboyard, S.; Venteo, S.; François, F.; Mausset-Bonnefont, A.L.; Antonarakis, S.E.; et al. Tmprss3, a Transmembrane Serine Protease Deficient in Human DFNB8/10 Deafness, Is Critical for Cochlear Hair Cell Survival at the Onset of Hearing. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 17383–17397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.R.; Chia, C.; Wu, L.; Kujawa, S.G.; Liberman, M.C.; Goodrich, L.V. Sensory Neuron Diversity in the Inner Ear Is Shaped by Activity. Cell 2018, 174, 1229–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Peng, A.; Ge, S.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J. MiR-204 Suppresses Cochlear Spiral Ganglion Neuron Survival Invitro by Targeting TMPRSS3. Hear. Res. 2014, 314, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, H.S.; Kudoh, J.; Wattenhofer, M.; Shibuya, K.; Berry, A.; Chrast, R.; Guipponi, M.; Wang, J.; Kawasaki, K.; Asakawa, S.; et al. Insertion of β-Satellite Repeats Identifies a Transmembrane Protease Causing Both Congenital and Childhood Onset Autosomal Recessive Deafness. Nat. Genet. 2001, 27, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonne-Tamir, B.; DeStefano, A.L.; Briggs, C.E.; Adair, R.; Franklyn, B.; Weiss, S.; Korostishevsky, M.; Frydman, M.; Baldwin, C.T.; Farrer, L.A. Linkage of Congenital Recessive Deafness (Gene DFNB10) to Chromosome 21q22.3. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1996, 58, 1254–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Weegerink, N.J.D.; Schraders, M.; Oostrik, J.; Huygen, P.L.M.; Strom, T.M.; Granneman, S.; Pennings, R.J.E.; Venselaar, H.; Hoefsloot, L.H.; Elting, M.; et al. Genotype-Phenotype Correlation in DFNB8/10 Families with TMPRSS3 Mutations. JARO J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2011, 12, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagawa, M.; Nishio, S.Y.; Sakurai, Y.; Hattori, M.; Tsukada, K.; Moteki, H.; Kojima, H.; Usami, S.I. The Patients Associated with TMPRSS3 Mutations Are Good Candidates for Electric Acoustic Stimulation. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2015, 124, 193S–204S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppsteiner, R.W.; Shearer, A.E.; Hildebrand, M.S.; DeLuca, A.P.; Ji, H.; Dunn, C.C.; Black-Ziegelbein, E.A.; Casavant, T.L.; Braun, T.A.; Scheetz, T.E.; et al. Prediction of Cochlear Implant Performance by Genetic Mutation: The Spiral Ganglion Hypothesis. Hear. Res. 2012, 292, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofatter, J.A.; MacCollin, M.M.; Rutter, J.L.; Murrell, J.R.; Duyao, M.P.; Parry, D.M.; Eldridge, R.; Kley, N.; Menon, A.G.; Pulaski, K. A Novel Moesin-, Ezrin-, Radixin-Like Gene Is a Candidate for the Neurofibromatosis 2 Tumor Suppressor. Cell 1993, 75, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welling, D.B.; Guida, M.; Goll, F.; Pearl, D.K.; Glasscock, M.E.; Pappas, D.G.; Linthicum, F.H.; Rogers, D.; Prior, T.W. Mutational Spectrum in the Neurofibromatosis Type 2 Gene in Sporadic and Familial Schwannomas. Hum. Genet. 1996, 98, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dornhoffer, J.R.; Plitt, A.R.; Lohse, C.M.; Driscoll, C.L.W.; Neff, B.A.; Saoji, A.A.; Van Gompel, J.J.; Link, M.J.; Carlson, M.L. Comparing Speech Recognition Outcomes Between Cochlear Implants and Auditory Brainstem Implants in Patients with NF2-Related Schwannomatosis. Otol. Neurotol. 2024, 1, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchman, C.A.; Roush, P.A.; Teagle, H.F.B.; Brown, C.J.; Zdanski, C.J.; Grose, J.H. Auditory Neuropathy Characteristics in Children with Cochlear Nerve Deficiency. Ear Hear. 2006, 27, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casselman, J.W.; E Offeciers, F.; Govaerts, P.J.; Kuhweide, R.; Geldof, H.; Somers, T.; D’Hont, G. Aplasia and hypoplasia of the vestibulocochlear nerve: Diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiology 1997, 202, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glastonbury, C.M.; Davidson, H.C.; Harnsberger, H.R.; Butler, J.; Kertesz, T.R.; Shelton, C. Imaging findings of cochlear nerve deficiency. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2002, 23, 635–643. [Google Scholar]

- Xoinis, K.; Weirather, Y.; Mavoori, H.; Shaha, S.H.; Iwamoto, L.M. Extremely low birth weight infants are at high risk for auditory neuropathy. J. Perinatol. 2007, 27, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenraad, S.; Goedegebure, A.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Hoeve, L. Risk factors for auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder in NICU infants compared to normal-hearing NICU controls. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 852–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.M.; Te-Selle, M.E. Cochlear microphonics in the jaundiced Gunn rat. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 1994, 15, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlee, J.W.; Shapiro, S.M. Morphological changes in the cochlear nucleus and nucleus of the trapezoid body in Gunn rat pups. Hear. Res. 1991, 57, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrmann-Müller, D.; Cebulla, M.; Rak, K.; Scheich, M.; Back, D.; Hagen, R.; Shehata-Dieler, W. Evaluation and Therapy Outcome in Children with Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder (ANSD). Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 127, 109618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, W.J.; Roche, J.P.; Giardina, C.K.; Harris, M.S.; Bastian, Z.J.; Fontenot, T.E.; Buchman, C.A.; Brown, K.D.; Adunka, O.F.; Fitzpatrick, D.C. Intraoperative Electrocochleographic Characteristics of Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder in Cochlear Implant Subjects. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudewyns, A.; Declau, F.; van den Ende, J.; Hofkens, A.; Dirckx, S.; Van de Heyning, P. Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder (ANSD) in Referrals from Neonatal Hearing Screening at a Well-Baby Clinic. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2016, 175, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attias, J.; Raveh, E.; Aizer-Dannon, A.; Bloch-Mimouni, A.; Fattal-Valevski, A. Auditory System Dysfunction Due to Infantile Thiamine Deficiency: Long-Term Auditory Sequelae. Audiol. Neurotol. 2012, 17, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadokoro, K.; Bartindale, M.R.; El-Kouri, N.; Moore, D.; Britt, C.; Kircher, M. Cochlear Implantation in Vestibular Schwannoma: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull. Base 2021, 82, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagannathan, J.; Lonser, R.R.; Stanger, R.A.; Butman, J.A.; Vortmeyer, A.O.; Zalewski, C.K.; Brewer, C.; Surowicz, C.; Kim, H.J. Cochlear implantation for hearing loss associated with bilateral endolymphatic sac tumors in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Otol. Neurotol. 2007, 28, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Ferch, R.; Eisenberg, R. Simultaneous cochlear implantation during resection of a cerebellopontine angle meningioma: Case report. Cochlear Implant. Int. 2023, 24, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celesia, G.G. Hearing disorders in brainstem lesions. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2015, 129, 509–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pressnitzer, D.; Sayles, M.; Micheyl, C.; Winter, I.M. Perceptual organization of sound begins in the auditory periphery. Curr. Biol. 2008, 18, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, S.J.; David, S.V. Rapid task-related plasticity of spectrotemporal receptive fields in the auditory midbrain. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 13090–13102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, R.A.; Gourévitch, B.; Portfors, C.V. Subcortical pathways: Towards a better understanding of auditory disorders. Hear. Res. 2018, 362, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suga, N. Role of corticofugal feedback in hearing. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural. Behav. Physiol. 2008, 194, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregman, A.S. Auditory Scene Analysis: The Perceptual Organisation of Sound; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Nelken, I.; Rotman, Y.; Bar, Y.O. Responses of auditory-cortex neurons to structural features of natural sounds. Nature 1999, 397, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamma, S.A.; Micheyl, C. Behind the scenes of auditory perception. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010, 20, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J.S.; Elhilali, M. Recent advances in exploring the neural underpinnings of auditory scene perception. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1396, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Audiology. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Children and Adults with Central Auditory Processing Disorder. 2010. Available online: https://www.audiology.org/document-type/clinical-practice-guideline/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- British Society of Audiology (BSA). Position Statement and Practice Guidance: Auditory Processing Disorder (APD), February 2018. Available online: https://www.thebsa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Position-Statement-and-Practice-Guidance-APD-2018.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Musiek, F.E.; Bellis, T.J.; Chermak, G.D. Nonmodularity of the central auditory nervous system: Implications for (central) auditory processing disorder. Am. J. Audiol. 2005, 14, 128–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medwetsky, L. Spoken language processing model: Bridging auditory and language processing to guide assessment and intervention. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2011, 42, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitto, M.; Motta, N.; Aldè, M.; Zanetti, D.; Di Berardino, F. Auditory Processing Disorders: Navigating the Diagnostic Maze of Central Hearing Losses. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarabichi, O.; Kozin, E.; Kanumuri, V.; Barber, S.; Ghosh, S.; Sitek, K.; Reinshagen, K.; Herrmann, B.; Remenschneider, A.; Lee, D. Diffusion Tensor Imaging of Central Auditory Pathways in Patients with Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 158, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Bhagavatula, I.; Konar, S.; Kaushal, S.; Hr, A. Reorganization of central auditory pathways in vestibular schwannoma: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Neuroradiology 2025, 67, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.J.; Arnott, W. Using different criteria to diagnose (central) auditory processing disorder: How big a difference does it make? J. Speech Lang. Hear Res. 2013, 56, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golding, M.; Carter, N.; Mitchell, P.; Hood, L.J. Prevalence of central auditory processing (CAP) abnormality inANSDolder Australian population: The Blue Mountains Hearing Study. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2004, 15, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stach, B.A.; Spretnjak, M.L.; Jerger, J. The prevalence of central presbyacusis in a clinical population. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 1990, 1, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bamiou, D.E.; Musiek, F.E.; Luxon, L.M. Aetiology and clinical presentations of auditory processing disorders—A review. Arch. Dis. Child. 2001, 85, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furst, M.; Aharonson, V.; Levine, R.A.; Fullerton, B.C.; Tadmor, R.; Pratt, H.; Polyakov, A.; Korczyn, A.D. Sound lateralization and interaural discrimination. Effects of brainstem infarcts and multiple sclerosis lesions. Hear. Res. 2000, 143, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, M.; Thai-Van, H.; Ptok, M.; Glarou, E.; Veuillet, E.; Miller, S.; Reynard, P.; Grech, H.; Utoomprurkporn, N.; Sereti, A.; et al. A systematic review and metanalysis of questionnaires used for auditory processing screening and evaluation. Front Neurol. 2023, 14, 1243170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristidou, I.L.; Hohman, M.H. Central Auditory Processing Disorder. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK587357/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Zheng, S.; Chen, C. Auditory processing deficits in autism spectrum disorder: Mechanisms, animal models, and therapeutic directions. J. Neural. Transm. 2025, 132, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, C.C.; Zalewski, C.K.; King, K.A.; Zobay, O.; Riley, A.; Ferguson, M.A.; Bird, J.E.; McCabe, M.M.; Hood, L.J.; Drayna, D.; et al. Heritability of non-speech auditory processing skills. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 24, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Chen, G.; Jeon, S.; Ling, L.; Manohar, S.; Ding, D.; Auerbach, B.D.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.K.; Sun, W. Foxg1 gene mutation impairs auditory cortex response and reduces sound tolerance. Cereb. Cortex 2025, 35, bhaf166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrino, P.A.; Newbury, D.F.; Fitch, R.H. Peripheral Anomalies in USH2A Cause Central Auditory Anomalies in a Mouse Model of Usher Syndrome and CAPD. Genes 2021, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannula, S.; Bloigu, R.; Majamaa, K.; Sorri, M.; Mäki-Torkko, E. Self-reported hearing problems among older adults: Prevalence and comparison to measured hearing impairment. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2011, 22, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spankovich, C.; Gonzalez, V.B.; Su, D.; Bishop, C.E. Self reported hearing difficulty, tinnitus, and normal audiometric thresholds, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Hear. Res. 2018, 358, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, D.L.; Danhauer, J.L. Amplification for adults with hearing difficulty, speech in noise problems—And normal thresholds. J. Otolaryngol. ENT Res. 2019, 11, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Lei, D.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, H.; Wang, L. Current Understanding of Hearing Loss in Sporadic Vestibular Schwannomas: A Systematic Review. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 687201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Han, S.; Kim, B.; Suh, M.; Lee, J.; Oh, S.; Park, M. Changes in microRNA Expression in the Cochlear Nucleus and Inferior Colliculus after Acute Noise-Induced Hearing Loss. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.; Gonçalves, R.; Taveira, I.; Mouzinho, M.; Osório, R.; Nzwalo, H. Stroke-Associated Cortical Deafness: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Radiological Characteristics. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamiou, D.; Werring, D.; Cox, K.; Stevens, J.; Musiek, F.; Brown, M.; Luxon, L. Patient-Reported Auditory Functions After Stroke of the Central Auditory Pathway. Stroke 2012, 43, 1285–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohi, N.; Vickers, D.; Chandrashekar, H.; Tsang, B.; Werring, D.; Bamiou, D.E. Auditory rehabilitation after stroke: Treatment of auditory processing disorders in stroke patients with personal frequency-modulated (FM) systems. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaastra, B.; Whyte, S.; Hankin, B.; Bulters, D.; Galea, I.; Campbell, N. ANSD assistive listening device improves hearing following aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Eur. J. Neurol. 2024, 31, e16240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stadio, A.; Dipietro, L.; Ralli, M.; Meneghello, F.; Minni, A.; Greco, A.; Stabile, M.; Bernitsas, E. Sudden hearing loss asANSDearly detector of multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 4611–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, M.S.; Hutter, M.; Lilly, D.J.; Bourdette, D.; Saunders, J.; Fausti, S.A. Frequency-modulation (FM) technology as a method for improving speech perception in noise for individuals with multiple sclerosis. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2006, 17, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, N.K. Hearing Loss and Cognitive Decline in the Aging Population: Emerging Perspectives in Audiology. Audiol. Res. 2024, 14, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillion, J.P.; Shiffler, D.E.; Hoon, A.H.; Lin, D.D. Severe auditory processing disorder secondary to viral meningoencephalitis. Int. J. Audiol. 2014, 53, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergemalm, P.O.; Lyxell, B. Appearances are deceptive? Long-term cognitive and central auditory sequelae from closed head injury. Int. J. Audiol. 2005, 44, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallun, F.J.; Diedesch, A.C.; Kubli, L.R.; Walden, T.C.; Folmer, R.L.; Lewis, M.S.; McDermott, D.J.; Fausti, S.A.; Leek, M.R. Performance on tests of central auditory processing by individuals exposed to high-intensity blasts. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2012, 49, 1005–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, K.N.; Succop, P.A.; Berger, O.G.; Keith, R.W. Lead exposure and the central auditory processing abilities and cognitive development of urban children: The Cincinnati Lead Study cohort at age 5 years. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 1992, 14, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curti, S.A.; Taylor, E.N.; Su, D.; Spankovich, C. Prevalence of and Characteristics Associated with Self-reported Good Hearing in a Population With Elevated Audiometric Thresholds. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 145, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetow, R.W.; Sabes, J.H. The need for and development of ANSD adaptive Listening and Communication Enhancement (LACE) Program. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2006, 17, 538–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamiou, D.E.; Campbell, N.; Sirimanna, T. Management of auditory processing disorders. Audiol. Med. 2006, 4, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihing, J.; Chermak, G.D.; Musiek, F.E. Auditory Training for Central Auditory Processing Disorder. Semin. Hear. 2015, 36, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominici Sanfins, M.; de Andrade, A.N.; Donadon, C.; Skarzynski, P.H.; Colella-Santos, M.F. Tools used to treat central auditory processing disorders: A critical analysis. Medincus 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiek, F.E.; Baran, J.A.; Shinn, J. Assessment and remediation of ANSD auditory processing disorder associated with head trauma. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2004, 15, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheich, H. Auditory cortex: Comparative aspects of maps and plasticity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1991, 1, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, N.; McGee, T.; Carrell, T.D.; King, C.; Tremblay, K.; Nicol, T. Central auditory system plasticity associated with speech discrimination training. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1995, 7, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jirsa, R. The clinical utility of the P3 AERP in children with auditory processing disorders. J. Speech Hear. Res. 1993, 35, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, B.; Skoe, E.; Kraus, N. ANSD integrative model of subcortical auditory plasticity. Brain Topogr. 2014, 27, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kral, A.; Eggermont, J.J. What’s to lose and what’s to learn: Development under auditory deprivation, cochlear implants and limits of cortical plasticity. Brain Res. Rev. 2007, 56, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, N.Y.S.; Nouchi, R.; Oba, K.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Kawashima, R. Auditory Cognitive Training Improves Brain Plasticity in Healthy Older Adults: Evidence From a Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 826672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, R.F.; Henson, O.W., Jr. The descending auditory pathway and acousticomotor systems: Connections with the inferior colliculus. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1990, 15, 295–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichora-Fuller, M.K.; Singh, G. Effects of age on auditory and cognitive processing: Implications for hearing aid fitting and audiologic rehabilitation. Trends Amplif. 2006, 10, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musiek, F.E.; Shinn, J.; Harel, C. Plasticity, Auditory Training, and Auditory Processing Disorders. Semin. Hear. 2002, 23, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chermak, G.D.; Musiek, F.E. Auditory Training: Principles and Approaches for Remediating and Managing Auditory Processing Disorders. Semin. Hear. 2002, 23, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellis, T.J. Developing deficit-specific intervention plans for individuals with auditory processing disorders. Semin. Hear. 2002, 23, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiek, F.E.; Baran, J.A.; Schochat, E. Selected management approaches to central auditory processing disorders. Scand. Audiol. Suppl. 1999, 51, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Moncrieff, D.; Keith, W.; Abramson, M.; Swann, A. Evidence of binaural integration benefits following ARIA training for children and adolescents diagnosed with amblyaudia. Int. J. Audiol. 2017, 56, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallal, P. Fast ForWord®: The birth of the neurocognitive training revolution. Prog. Brain Res. 2013, 207, 175–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S.; White-Schwoch, T.; Choi, H.J.; Kraus, N. Training changes processing of speech cues in older adults with hearing loss. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, J.H.; Bamiou, D.E.; Campbell, N.; Luxon, L.M. Computer-based auditory training (CBAT): Benefits for children with language- and reading-related learning difficulties. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2010, 52, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward, K.E.; Hall, R.L.; Ferguson, M.A.; Moore, D.R. Training speech-in-noise perception in mainstream school children. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2011, 75, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.R.; Rosenberg, J.F.; Coleman, J.S. Discrimination training of phonemic contrasts enhances phonological processing in mainstream school children. Brain Lang. 2005, 94, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillam, R.B.; Loeb, D.F.; Hoffman, L.M.; Bohman, T.; Champlin, C.A.; Thibodeau, L.; Widen, J.; Brandel, J.; Friel-Patti, S. The efficacy of Fast ForWord Language intervention in school-age children with language impairment: A randomized controlled trial. J. Speech Lang Hear. Res. 2008, 51, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putter-Katz, H.; Adi-Bensaid, L.; Feldman, I.; Hildesheimer, M. Effects of speech in noise and dichotic listening intervention programs on central auditory processing disorders. J. Basic Clin. Physiol Pharmacol. 2008, 19, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fey, M.E.; Richard, G.J.; Geffner, D.; Kamhi, A.G.; Medwetsky, L.; Paul, D.; Ross-Swain, D.; Wallach, G.P.; Frymark, T.; Schooling, T. Auditory processing disorder and auditory/language interventions:ANSDevidence-based systematic review. Lang Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2011, 42, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Purdy, S.C.; Kelly, A.S. A randomized control trial of interventions in school-aged children with auditory processing disorders. Int. J. Audiol. 2012, 51, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, J.H.; Rosen, S.; Bamiou, D.E. Auditory Training Effects on the Listening Skills of Children With Auditory Processing Disorder. Ear Hear. 2016, 37, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crum, R.; Chowsilpa, S.; Kaski, D.; Giunti, P.; Bamiou, D.E.; Koohi, N. Hearing rehabilitation of adults with auditory processing disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of current evidence-based interventions. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1406916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.; Kitterick, P.; Chong, L.; Edmondson-Jones, M.; Barker, F.; Hoare, D. Hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 9, CD012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humes, L.; Rogers, S.; Quigley, T.; Main, A.; Kinney, D.; Herring, C. The Effects of Service-Delivery Model and Purchase Price on Hearing-Aid Outcomes in Older Adults: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Am. J. Audiol. 2017, 26, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, H.; Sharma, A. Cortical Neuroplasticity and Cognitive Function in Early-Stage, Mild-Moderate Hearing Loss: Evidence of Neurocognitive Benefit From Hearing Aid Use. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morvan, P.; Buisson-Savin, J.; Boiteux, C.; Bailly-Masson, E.; Buhl, M.; Thai-Van, H. Factors in the Effective Use of Hearing Aids among Subjects with Age-Related Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madden, C.; Rutter, M.; Hilbert, L.; Greinwald, J.H., Jr.; Choo, D.I. Clinical and audiological features in auditory neuropathy. Arch Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2002, 128, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, C.I.; Hood, L.J.; Morlet, T.; Wilensky, D.; Li, L.; Mattingly, K.R.; Taylor-Jeanfreau, J.; Keats, B.J.B.; John, P.S.; Montgomery, E.; et al. Multi-Site Diagnosis and Management of 260 Patients with Auditory Neuropathy/Dys-Synchrony (Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder). Int. J. Audiol. 2010, 49, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, F.; Oba, S.; Garde, S.; Sininger, Y.; Starr, A. Temporal and speech processing deficits in auditory neuropathy. NeuroReport 1999, 10, 3429–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rance, G.; McKay, C.; Grayden, D. Perceptual characterization of children with auditory neuropathy. Ear Hear. 2004, 25, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javel, E. Basic response properties of auditory nerve fibers. In Neurobiology of Hearing: The Cochlea; Altschuler, R.A., Hoffman, R.P., Eds.; Raven Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 213–245. [Google Scholar]

- Rance, G.; Cone-Wesson, B.; Wunderlich, J.; Dowell, R. Speech perception and cortical event related potentials in children with auditory neuropathy. Ear Hear. 2002, 23, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rance, G.; Barker, E.J.; Sarant, J.Z.; Ching, T.Y. Receptive language and speech production in children with auditory neuropathy/dyssynchrony type hearing loss. Ear Hear. 2007, 28, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raveh, E.; Buller, N.; Badrana, O.; Attias, J. Auditory neuropathy: Clinical characteristics and therapeutic approach. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2007, 28, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teagle, H.F.; Roush, P.A.; Woodard, J.S.; Hatch, D.R.; Zdanski, C.J.; Buss, E.; Buchman, C.A. Cochlear Implantation in Children with Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder. Ear Hear. 2010, 31, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Audiology. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Pediatric Amplification; American Academy of Audiology: Reston, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roush, P.A.; Frymakr, T.; Venediktov, R.; Wang, B. Audiologic management of auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder in children: A systematic review of the literature. Am. J. Audiol. 2011, 20, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphriss, R.; Hall, A.; Maddocks, J.; Macleod, J.; Sawaya, K.; Midgley, E. Does cochlear implantation improve speech recognition in children with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder? A systematic review. Int. J. Audiol. 2013, 52, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ching, T.Y.; Day, J.; Dillon, H.; Gardner-Berry, K.; Hou, S.; Seeto, M.; Zhang, V. Impact of the presence of auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) on outcomes of children at three years of age. Int. J. Audiol. 2013, 52, S55–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.; McCreery, R.; Spratford, M.; Roush, P. Children with Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder Fitted with Hearing AIDS Applying the American Academy of Audiology Pediatric Amplification Guideline: Current Practice and Outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2016, 27, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuk, F.; Jackson, A.; Keenan, D.; Lau, C.C. Personal amplification for school-age children with auditory processing disorders. J. Am. Acad Audiol. 2008, 19, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roup, C.M.; Post, E.; Lewis, J. Mild-Gain Hearing Aids as a Treatment for Adults with Self-Reported Hearing Difficulties. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2018, 29, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medical Devices: Ear, Nose and Throat Devices. Establishing Over the Counter Hearing Aids. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2022-08-17/pdf/2022-17230.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Manchaiah, V.; Taylor, B.; Dockens, A.L.; Tran, N.R.; Lane, K.; Castle, M.; Grover, V. Applications of direct-to-consumer hearing devices for adults with hearing loss: A review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sousa, K.C.; Manchaiah, V.; Moore, D.R.; Graham, M.A.; Swanepoel, W. Effectiveness of ANSD Over-the-Counter Self-fitting Hearing Aid Compared with an Audiologist-Fitted Hearing Aid: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 149, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sousa, K.C.; Manchaiah, V.; Moore, D.R.; Graham, M.A.; Swanepoel, W. Long-Term Outcomes of Self-Fit vs Audiologist-Fit Hearing Aids. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2024, 150, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabin, A.T.; Van Tasell, D.J.; Rabinowitz, B.; Dhar, S. Validation of a self-fitting method for over-the-counter hearing aids. Trends Hear. 2020, 24, 2331216519900589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Convery, E.; Keidser, G.; Hickson, L.; Meyer, C. Factors associated with successful setup of a self-fitting hearing aid and the need for personalized support. Ear Hear. 2019, 40, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humes, L.E.; Kinney, D.L.; Main, A.K.; Rogers, S.E. A follow-up clinical trial evaluating the consumer-decides service delivery model. Am. J. Audiol. 2019, 28, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Huang, C.-Y.; Cheng, H.-L.; Lin, H.-Y.H.; Chu, Y.-C.; Chang, C.-Y.; Lai, Y.-H.; Wang, M.-C.; Cheng, Y.-F. Comparison of personal sound amplification products and conventional hearing aids for patients with hearing loss: A systematic review with meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 46, 101378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, K.N.; John, A.B.; Kreisman, N.V.; Hall, J.W.; Crandell, C.C. Multiple benefits of personal FM system use by children with auditory processing disorder (APD). Int. J. Audiol. 2009, 48, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, J.L.; Purdy, S.C.; Kelly, A.S. Impact of personal frequency modulation systems on behavioral and cortical auditory evoked potential measures of auditory processing and classroom listening in school-aged children with auditory processing disorder. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2018, 19, 568–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrinos, G.; Iliadou, V.V.; Pavlou, M.; Bamiou, D.E. Remote Microphone Hearing Aid Use Improves Classroom Listening, Without Adverse Effects on Spatial Listening and Attention Skills, in Children With Auditory Processing Disorder: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starr, A. “Hearing” and Auditory Neuropathy: Lessons from Patients, Physiology, and Genetics. In Neuropathies of the Auditory and Vestibular Eighth Cranial Nerves; Kaga, K., Starr, A., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2009; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Santarelli, R. Information from cochlear potentials and genetic mutations helps localize the lesion site in auditory neuropathy. Genome. Med. 2010, 2, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santarelli, R.; del Castillo, I.; Scimemi, P.; Cama, E.; Starr, A. Audibility, speech perception and processing of temporal cues in ribbon synaptic disorders due to OTOF mutations. Hear. Res. 2015, 330, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akil, O.; Dyka, F.; Calvet, C.; Emptoz, A.; Lahlou, G.; Nouaille, S.; de Monvel, J.B.; Hardelin, J.-P.; Hauswirth, W.W.; Avan, P.; et al. Dual AAV-mediated gene therapy restores hearing in a DFNB9 mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4496–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santarelli, R.; Scimemi, P.; Costantini, M.; Domínguez-Ruiz, M.; Rodríguez-Ballesteros, M. Cochlear synaptopathy due to mutations in OTOF gene may result in stable mild hearing loss and severe impairment of speech perception. Ear Hear. 2021, 42, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frezza, C.; Cipolat, S.; de Brito, O.M.; Micaroni, M.; Beznoussenko, G.V.; Rudka, T.; Bartoli, D.; Polishuck, R.S.; Danial, N.N.; De Strooper, B.; et al. OPA1 controls apoptotic cristae remodeling independently from mitochondrial fusion. Cell 2006, 126, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, R.; Tonon, C.; Valentino, M.L.; Iotti, S.; Clementi, V.; Malucelli, E.; Barboni, P.; Longanesi, L.; Schimpf, S.; Wissinger, B.; et al. Deficit of in vivo mitochondrial ATP production in OPA1-related dominant optic atrophy. Ann. Neurol. 2004, 56, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olichon, A.; Guillou, E.; Delettre, C.; Landes, T.; Arnauné-Pelloquin, L.; Emorine, L.J.; Mils, V.; Daloyau, M.; Hamel, C.; Amati-Bonneau, P.; et al. Mitochondrial dynamics and disease, OPA1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1763, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amati-Bonneau, P.; Valentino, M.L.; Reynier, P.; Gallardo, M.E.; Bornstein, B.; Boissière, A.; Campos, Y.; Rivera, H.; de la Aleja, J.G.; Carroccia, R.; et al. OPA1 mutations induce mitochondrial DNA instability and optic atrophy “plus” phenotypes. Brain 2008, 131, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carelli, V.; Ross-Cisneros, F.N.; Sadun, A.A. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a cause of optic neuropathies. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2004, 23, 53–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.A.; Morgan, J.E.; Votruba, M. OPA1 deficiency in a mouse model of dominant optic atrophy leads to retinal ganglion cell dendropathy. Brain 2010, 133, 2942–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, D.; Chaudhry, A.; Muzaffar, J.; Monksfield, P.; Bance, M. Cochlear Implantation Outcomes in Post Synaptic Auditory Neuropathies: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 2020, 16, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarelli, R.; Cama, E.; Scimemi, P.; La Morgia, C.; Caporali, L.; Valentino, M.L.; Liguori, R.; Carelli, V. Reply: Both mitochondrial DNA and mitonuclear gene mutations cause hearing loss through cochlear dysfunction. Brain 2016, 139, E34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truesdale, S.P. Whole body listening updated. Adv. Speech-Lang. Pathol. Audiol. 2013, 23, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chermak, G.D.; Musiek, F.E. Handbook of Central Auditory Processing: Comprehensive Intervention Disorder, 2nd ed.; Plural Publishing Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Osisanya, A.; Adewunmi, A.T. Evidence-based interventions of dichotic listening training, compensatory strategies and combined therapies in managing pupils with auditory processing disorders. Int. J. Audiol. 2018, 57, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mechanism | Clinical Presentation | Gene Involved | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distal auditory neuropathy (dendritic/somatic post-synaptic synaptopathy) | Genetic | Optic atrophy, deafness | OPA1 codes for a mitochondrial protein that plays an important role in mitochondrial stability and energy output regulation | [19,20,22,23] |

| Non-syndromic SNHL | ROR1 codes for the receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 1, which plays an important role in the NF-κB pathway for neural outgrowth. Animal models have been correlated with deficiency of SGN axons and a lack of innervation of the sensory hair cell synapses | [24] | ||

| CAPOS Syndrome (Cerebellar Ataxia, Areflexia, Pes Cavus, Optic Atrophy, and SNHL) | ATP1A3 codes for the α3-subunit of the transmembrane Na/K-ATPase pump, implicated in the regulation of intra- and extra-cellular ion levels | [25,26,27,28] | ||

| Clinical and electrophysiological findings, along with the good results obtained after cochlear implantation, suggest a nonsyndromic autosomal dominant auditory neuropathy 1 (AUNA1) via a synaptic lesion, listing DIAPH3 mutations as a postsynaptic neuropathy | DIAPH3 codes for the diaphanous homolog 3, involved in cytoskeleton dynamics whose function at the synaptic and neural sites remains unclear | [29,30,31,32] | ||

| Non genetic | Intralabyrinthine schwannoma | [33,34] | ||

| Proximal auditory neuropathy (axonal/somatic) | Genetic | Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (CMT) | MPZ, PMP22 are both correlated to ANSD phenotype SGNs fiber demyelination | [35,36,37] |

| Friedreich ataxia | SGNs fiber demyelination | [38] | ||

| Deafness–dystonia–optic neuropathy (DDON or Mohr–Tranebjaerg syndrome) X-linked | TIMM8A deafness–dystonia peptide-1/translocase of mitochondrial inner membrane 8A (DDP1/TIMM8A) is a protein involved in the transfer of metabolites into the mitochondrial inner membrane from the cytoplasm | [39,40,41] | ||

| Cowchock syndrome | AIFM1 codes for a flavin adenine of the mitochondrial intermembrane space, the apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondria-associated-1, expressed in inner and outer hair cells and in SGNs (delayed onset nerve hypoplasia) | [42,43,44] | ||

| Auditory neuropathy DFNB94 and Leigh syndrome | NARS2 (SGN) | [45] | ||

| Auditory neuropathy DFNB59 (noise induced) | Pejvakin (SGN) | [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53] | ||

| DFNB8 DFNB10 (AN) | TMPRSS3 The transmembrane serine protease 3 is broadly expressed in peripheral hearing pathways, notably in type II SGNs, and is involved in hair cells’ and spiral ganglion cells’ survival | [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62] | ||

| Neurofibromatosis type 2 | NF2 (more of 200 alterations found) Code for Merlin, which has tumor suppressing properties | [63,64,65] | ||

| Non genetic | Cochlear nerve deficiency (hypoplasia or aplasia) | [66,67,68] | ||

| Dysmaturity, fetal infection (measles, mumps, CMV) | [69] | |||

| Perinatal disorder (hypoxia with mechanical ventilation, hyperbilirubinemia, septicemia), Ototoxic drugs, Meningitis | [7,70,71,72,73,74,75] | |||

| Thiamine deficiency | [76] | |||

| IAC or CPA neoplasm (sporadic vestibular schwannoma, meningioma, endolymphatic sac tumors, etc.) | [77,78,79] |

| Hair Cells | Auditory Nerve | Cochlear Nucleus | Superior Olive | Inferior Colliculus | Thalamus | Cortex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase locking | +++++ | +++++ | ++++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Neural adaptation | + | + | ++ | +++ | ++++ | +++++ | |

| Gap detection | + | + | ++ | +++ | ++++ | +++++ | |

| Spectral integration | + | ++ | +++ | ++++ | +++++ | +++++ | |

| Noise filtering | + | ++ | +++ | ++++ | +++++ | ||

| Spatial processing | +++++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ |

| Children | ||||

| Risk Factors | Clinical Presentation | Mechanism | Ref. | |

| Isolated | Delayed CNS maturation or other developmental disorders Prenatal/neonatal (anoxia, hypoxia, prematurity, drug exposure, hyperbilirubinemia, CMV) | Diffuse functional deficit; not necessarily associated with any structural lesion | [1,93,99,101,102] | |

| Associated (with neurological pathology) | Prematurity Low birth weight Epilepsy Cerebrovascular diseases Tumors Brain trauma Autism spectrum disorders | Varies based on primary diagnosis | [103] | |

| Genetic | There is evidence of auditory processing disorder (APD) in twin pairs. FOX syndrome auditory phenotypes | FOXG1 gene Heterozygous USH2A mutations are associated with changes in cochlear development, which may subsequently affect the development of brain regions involved in auditory processing CNTNAP2 | [103,104,105,106] | |

| Adults | ||||

| Risk factors | Clinical presentation | Mechanism | Ref. | |

| Isolated | Aging and exposure to noise Unmanaged APD in childhood | Peripheral and central multi-site damage | Expression of plasticity downstream of the receptor (post-synaptic) or primitive damage | [15,107,108,109] |

| Associated (with neurological pathology) | Tumors | Vestibular schwannoma Malignant (primary or secondary), including ependymomas and gliomas | Can induce degenerative changes in subcortical auditory pathways, especially the medial geniculate bodies and inferior colliculus, with compensatory reorganization in the auditory cortex. Neuroplasticity: The brain may attempt to reorganize auditory processing, especially in the cortex, to compensate for lost input, but this is often incomplete | [95,110,111] |

| Stroke | Ischemic stroke | Bilateral common Henle’s gyrus, severe midbrain deafness, subcortical lesions are rarer, possible recovery | [112,113,114] | |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | [115] | |||

| Multiple sclerosis | Fluctuating auditory disorders, tinnitus, or difficulty in understanding speech in noisy environments. Neurodegenerative diseases: Multiple sclerosis can present with sudden sensorineural HL | [116,117] | ||

| Neurodegenerative diseases | Alzheimer’s disease | [118] | ||

| Epilepsy | ||||

| Infections and inflammations | Encephalitis, myelitis | Often associated with fever and systemic disorders | [119] | |

| Head trauma | Closed head and traumatic brain injury | [120] | ||

| Blast injury | [121] | |||

| Neurotoxicity | Heavy metals | Lead exposure | [122] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cuda, D.; Mancini, P.; Chiarella, G.; Santarelli, R. Retrocochlear Auditory Dysfunctions (RADs) and Their Treatment: A Narrative Review. Audiol. Res. 2026, 16, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010005

Cuda D, Mancini P, Chiarella G, Santarelli R. Retrocochlear Auditory Dysfunctions (RADs) and Their Treatment: A Narrative Review. Audiology Research. 2026; 16(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuda, Domenico, Patrizia Mancini, Giuseppe Chiarella, and Rosamaria Santarelli. 2026. "Retrocochlear Auditory Dysfunctions (RADs) and Their Treatment: A Narrative Review" Audiology Research 16, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010005

APA StyleCuda, D., Mancini, P., Chiarella, G., & Santarelli, R. (2026). Retrocochlear Auditory Dysfunctions (RADs) and Their Treatment: A Narrative Review. Audiology Research, 16(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010005