Questioning the Usefulness of Stimulation Rate Changes to Optimize Perception in Cochlear Implant Users

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Search Strategy

3. Literature Overview

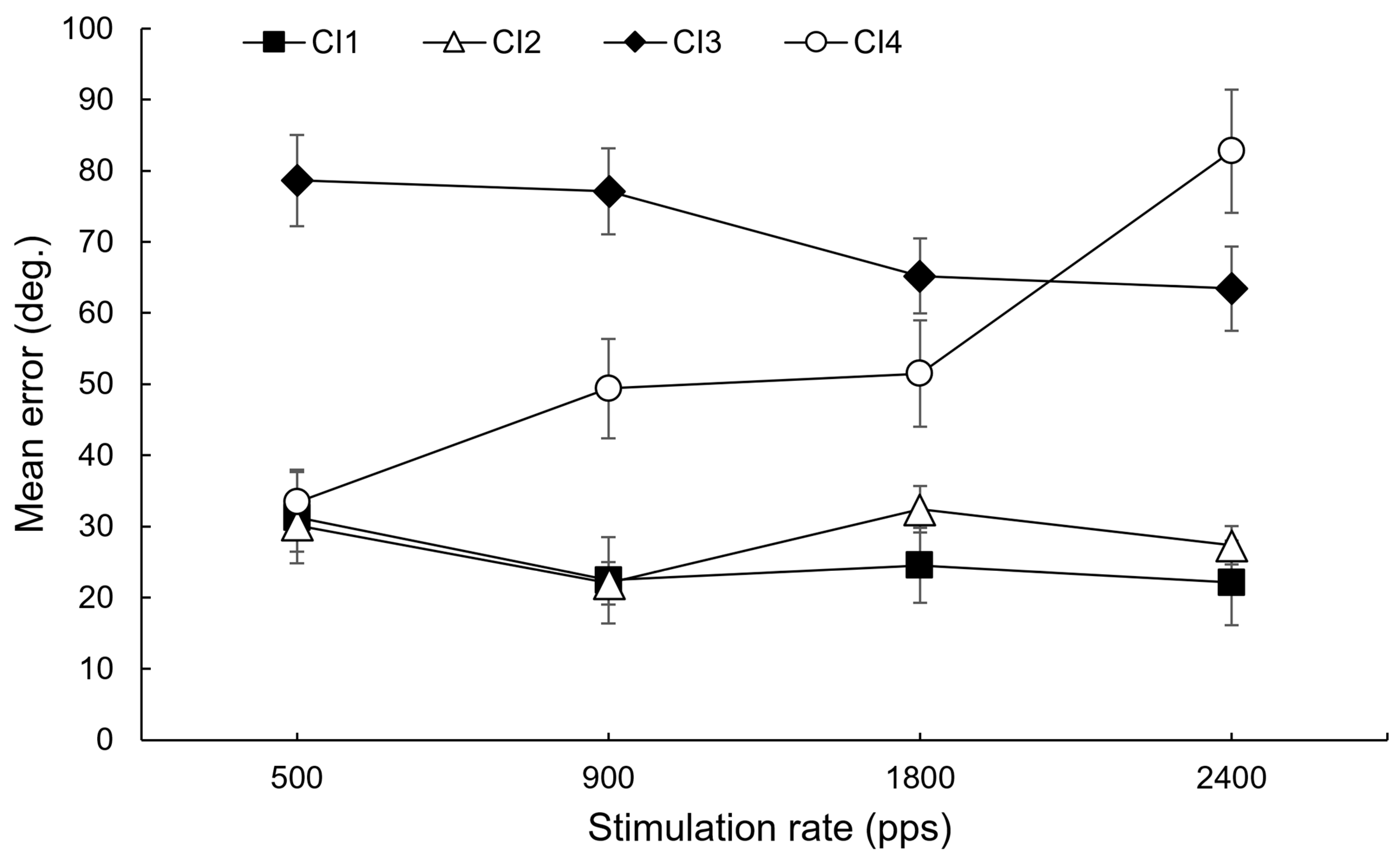

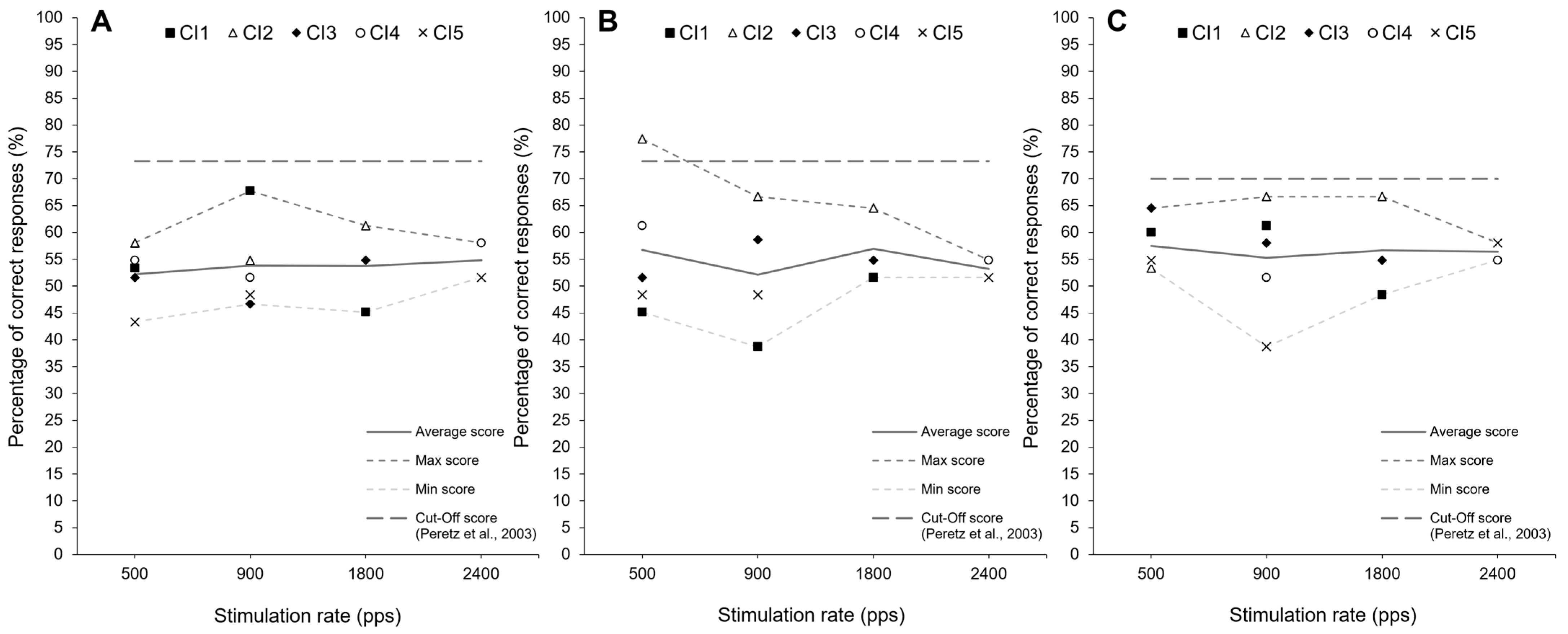

4. Observational Data

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data availability statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Damen, G.W.; Pennings, R.J.; Snik, A.F.; Mylanus, E.A. Quality of life and cochlear implantation in Usher syndrome type I. Laryngoscope 2006, 116, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammeyer, J. Congenitally deafblind children and cochlear implants: Effects on communication. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 2009, 14, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennings, R.J.; Damen, G.W.; Snik, A.F.; Hoefsloot, L.; Cremers, C.W.; Mylanus, E.A. Audiologic performance and benefit of cochlear implantation in Usher syndrome type I. Laryngoscope 2006, 116, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, R.H.; Shallop, J.K.; Peterson, A.M. Speech recognition materials and ceiling effects: Considerations for cochlear implant programs. Audiol. Neurotol. 2008, 13, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, L.K.; Finley, C.C.; Firszt, J.B.; Holden, T.A.; Brenner, C.; Potts, L.G.; Skinner, M.W. Factors affecting open-set word recognition in adults with cochlear implants. Ear Hear. 2013, 34, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blamey, P.J.; Sarant, J.Z. The consequences of deafness for spoken language development. In Deafness; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 265–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosetti, M.K.; Waltzman, S.B. Outcomes in cochlear implantation: Variables affecting performance in adults and children. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 45, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, K.; Vandali, A.; Dowell, R.; Dawson, P. Effects of stimulation rate on modulation detection and speech recognition by cochlear implant users. Int. J. Audiol. 2011, 50, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, K.; Plant, K.; Dawson, P.; Cowan, R. Effect of reducing electrical stimulation rate on hearing performance of Nucleus® cochlear implant recipients. Int. J. Audiol. 2025, 64, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkany, T.; Hodges, A.; Menapace, C.; Hazard, L.; Driscoll, C.; Gantz, B.; Kelsall, D.; Luxford, W.; McMenomy, S.; Neely, J.G.; et al. Nucleus Freedom North American clinical trial. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surgery 2007, 136, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buechner, A.; Frohne-Büchner, C.; Gaertner, L.; Stoever, T.; Battmer, R.D.; Lenarz, T. The Advanced Bionics High Resolution Mode: Stimulation rates up to 5000 pps. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2010, 130, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, L.M.; Shannon, R.V.; Cruz, R.J. Effects of stimulation rate on speech recognition with cochlear implants. Audiol. Neurootol. 2005, 10, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, L.K.; Skinner, M.W.; Holden, T.A.; Demorest, M.E. Effects of stimulation rate with the Nucleus 24 ACE speech coding strategy. Ear Hear. 2002, 23, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loizou, P.C.; Dorman, M.; Poroy, O.; Spahr, T. Speech recognition by normal-hearing and cochlear implant listeners as a function of intensity resolution. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2000, 108, 2377–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, M.W.; Arndt, P.L.; Staller, S.J. Nucleus 24 advanced encoder conversion study: Performance versus preference. Ear Hear. 2002, 23, 2S–17S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandali, A.E.; Whitford, L.A.; Plant, K.L.; Clark, G.M. Speech perception as a function of electrical stimulation rate: Using the Nucleus 24 cochlear implant system. Ear Hear. 2000, 21, 608–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, B.P.; Lai, W.K.; Dillier, N.; von Wallenberg, E.L.; Killian, M.J.; Pesch, J.; Battmer, R.D.; Lenarz, T. Performance and preference for ACE stimulation rates obtained with nucleus RP 8 and freedom system. Ear Hear. 2007, 28, 46S–48S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard-Demanze, L.; Léonard, J.; Dumitrescu, M.; Meller, R.; Magnan, J.; Lacour, M. Static and dynamic posture control in postlingual cochlear implanted patients: Effects of dual-tasking, visual and auditory inputs suppression. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2014, 7, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gfeller, K.; Christ, A.; Knutson, J.F.; Witt, S.; Murray, K.T.; Tyler, R.S. Musical backgrounds, listening habits, and aesthetic enjoyment of adult cochlear implant recipients. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2000, 11, 390–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limb, C.J.; Roy, A.T. Technological, biological, and acoustical constraints to music perception in cochlear implant users. Hear. Res. 2014, 308, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, H.J. Music perception with cochlear implants: A review. Trends Amplif. 2004, 8, 49–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, A.; Delcenserie, A.; Champoux, F. Auditory event-related potentials associated with music perception in cochlear implant users. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laback, B.; Majdak, P.; Baumgartner, W.D. Lateralization discrimination of interaural time delays in four-pulse sequences in electric and acoustic hearing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2007, 121, 2182–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noel, V.A.; Eddington, D.K. Sensitivity of bilateral cochlear implant users to fine-structure and envelope interaural time differences. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 133, 2314–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, R.S.; Dunn, C.C.; Witt, S.A.; Preece, J.P. Update on bilateral cochlear implantation. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2003, 11, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoesel, R.J. Sensitivity to binaural timing in bilateral cochlear implant users. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2007, 121, 2192–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hoesel, R.J.; Clark, G.M. Psychophysical studies with two binaural cochlear implant subjects. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1997, 102, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoesel, R.J.; Jones, G.L.; Litovsky, R.Y. Interaural time-delay sensitivity in bilateral cochlear implant users: Effects of pulse rate, modulation rate, and place of stimulation. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. JARO 2009, 10, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hoesel, R.J.; Tyler, R.S. Speech perception, localization, and lateralization with bilateral cochlear implants. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2003, 113, 1617–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadpour, M.; McKay, C.M.; Svirsky, M.A. Effect of Pulse Rate on Loudness Discrimination in Cochlear Implant Users. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2018, 19, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plant, K.; Holden, L.; Skinner, M.; Arcaroli, J.; Whitford, L.; Law, M.A.; Nel, E. Clinical evaluation of higher stimulation rates in the nucleus research platform 8 system. Ear Hear. 2007, 28, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, R.S.; Gfeller, K.; Mehr, M.A. A preliminary investigation comparing one and eight channels at fast and slow rates on music appraisal in adults with cochlear implants. Cochlear Implant. Int. 2000, 1, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, K.; Dawson, P.; Dowell, R.; Vandali, A. Electrical stimulation rate effects on speech perception in cochlear implants. Int. J. Audiol. 2009, 48, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, D.K.K. Effects of stimulation rates on Cantonese lexical tone perception by cochlear implant users in Hong Kong. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci. 2003, 28, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lella, F.; Bacciu, A.; Pasanisi, E.; Vincenti, V.; Guida, M.; Bacciu, S. Main peak interleaved sampling (MPIS) strategy: Effect of stimulation rate variations on speech perception in adult cochlear implant recipients using the Digisonic SP cochlear implant. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2010, 130, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frijns, J.H.; Klop, W.M.C.; Bonnet, R.M.; Briaire, J.J. Optimizing the number of electrodes with high-rate stimulation of the clarion CII cochlear implant. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2003, 123, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, J.; Von Ilberg, C.; Hubner-Egner, J.; Rupprecht, V.; Knecht, R. Optimized speech understanding with the continuous interleaved sampling speech coding strategy in patients with cochlear implants: Effect of variations in stimulation rate and number of channels. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2000, 109, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, K.; Barco, A.; Zeng, F.G. Spectral and temporal cues in cochlear implant speech perception. Ear Hear. 2006, 27, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psarros, C.E.; Plant, K.L.; Lee, K.; Decker, J.A.; Whitford, L.A.; Cowan, R.S.C. Conversion from the SPEAK to the ACE strategy in children using the Nucleus 24 cochlear implant system: Speech perception and speech production outcomes. Ear Hear. 2002, 23, 18S–27S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riss, D.; Hamzavi, J.S.; Blineder, M.; Flak, S.; Baumgartner, W.D.; Kaider, A.; Arnoldner, C. Effects of stimulation rate with the FS4 and HDCIS coding strategies in cochlear implant recipients. Otol. Neurotol. 2016, 37, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, R.V.; Cruz, R.J.; Galvin, J.J. Effect of stimulation rate on cochlear implant users’ phoneme, word and sentence recognition in quiet and in noise. Audiol. Neurotol. 2011, 16, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.J.; Shannon, R.V. Effect of stimulation rate on phoneme recognition by Nucleus-22 cochlear implant listeners. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2000, 107, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, K.A.; Chen, C.; Noble, J.H.; Dawant, B.M.; Dwyer, R.T.; Labadie, R.F.; Gifford, R.H. Effects of the Number of Channels and Channel Stimulation Rate on Speech Recognition and Sound Quality Using Precurved Electrode Arrays. Am. J. Audiol. 2023, 32, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, R.M.; Boermans, P.P.B.; Avenarius, O.F.; Briaire, J.J.; Frijns, J.H. Effects of pulse width, pulse rate and paired electrode stimulation on psychophysical measures of dynamic range and speech recognition in cochlear implants. Ear Hear. 2012, 33, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, D.; James, C.J. Stimulation rate and voice pitch perception in cochlear implants. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2022, 23, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuur, C.A.; Lutman, M.E.; Ramsden, R.; Greenham, P.; O’Driscoll, M. Auditory localization abilities in bilateral cochlear implant recipients. Otol. Neurotol. 2005, 26, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Kim, E.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, H.J. Effects of electrical stimulation rate on speech recognition in cochlear implant users. Korean J. Audiol. 2012, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shader, M.J.; Nguyen, N.; Cleary, M.; Hertzano, R.; Eisenman, D.J.; Anderson, S.; Gordon-Salant, S.; Goupell, M.J. Effect of stimulation rate on speech understanding in older cochlear-implant users. Ear Hear. 2020, 41, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, K.; Goldsworthy, R.; Noble, J.; Dawant, B.; Gifford, R. The relationship between channel interaction, electrode placement, and speech perception in adult cochlear implant users. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2024, 156, 4289–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S.; Easter, K.; Goupell, M.J. Effects of Rate and Age in Processing Interaural Time and Level Differences in Normal-Hearing and Bilateral Cochlear-Implant Listeners. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2019, 146, 3232–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Z.M.; Delgutte, B. Sensitivity to Interaural Time Differences in the Inferior Colliculus with Bilateral Cochlear Implants. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 6740–6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Z.M.; Delgutte, B. Sensitivity of Inferior Colliculus Neurons to Interaural Time Differences in the Envelope Versus the Fine Structure with Bilateral Cochlear Implants. J. Neurophysiol. 2008, 99, 2390–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmer, A.; Baumann, U. New parallel stimulation strategies revisited: Effect of synchronous multi electrode stimulation on rate discrimination in cochlear implant users. Cochlear Implant. Int. 2013, 14, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipo, R.; Ballantyne, D.; Mancini, P.; D’elia, C. Music perception in cochlear implant recipients: Comparison of findings between HiRes90 and HiRes120. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2008, 128, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfingst, B.E.; Xu, L.; Thompson, C.S. Effects of carrier pulse rate and stimulation site on modulation detection by subjects with cochlear implants. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2007, 121, 2236–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fastl, H.; Zwicker, E. Psychoacoustics: Facts and Models, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretz, I.; Champod, A.S.; Hyde, K. Varieties of Musical Disorders: The Montreal Battery of Evaluation of Amusia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003, 999, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, J.; Schafer, E. Programming Cochlear Implants; Plural Publishing: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanasingh, A.; Nielsen, S.B.; Beal, F.; Schilp, S.; Hessler, R.; Jolly, C. Cochlear implant electrode design for safe and effective treatment. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1348439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertas, Y.N.; Özpolat, D.; Karasu, S.N.; Ashammakhi, N. Recent advances in cochlear implant electrode array design parameters. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, J.; Schafer, E. Programming Cochlear Implants, 3rd ed.; Plural Publishing: San Diego, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard, N.; Uecker, F.C.; Hänsel, T.; Gauger, U.; Romo Ventura, E.; Olze, H.; Knopke, S.; Coordes, A. Duration of deafness impacts auditory performance after cochlear implantation: A meta-analysis. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2021, 6, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambriks, L.; van Hoof, M.; Debruyne, J.; Janssen, M.; Hof, J.; Hellingman, K.; Devocht, E.; George, E. Toward neural health measurements for cochlear implantation: The relationship among electrode positioning, the electrically evoked action potential, impedances, and behavioral stimulation levels. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1093265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, S.; Lévesque, J.; Champoux, F. Breaking News: Brain Plasticity an Obstacle for Cochlear Implant Rehabilitation. Hear. J. 2012, 65, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, S.P.; Guillemot, J.P.; Champoux, F. Temporary deafness can impair multisensory integration: A study of cochlear-implant users. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry, S.P.; Guillemot, J.P.; Champoux, F. Audiotactile interaction can change over time in cochlear implant users. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouger, J.; Lagleyre, S.; Fraysse, B.; Deneve, S.; Deguine, O.; Barone, P. Evidence that cochlear-implanted deaf patients are better multisensory integrators. Psychol. Cogn. Sci. 2007, 104, 7295–7300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, C.; Champoux, F.; Lepore, F.; Théoret, H. Audiovisual fusion and cochlear implant proficiency. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2010, 28, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collignon, O.; Champoux, F.; Voss, P.; Lepore, F. Sensory rehabilitation in the plastic brain. Prog. Brain Res. 2011, 191, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Authors | Sample Size | Rate Range (pps) | Key Findings | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed findings | |||||

| 2000 | Fu and Shannon [42] | 6 | 50–500 | <150 poorer; 150–500 equivalent | Cochlear |

| 2005 | Friesen et al. [12] | 12 | 200–5000 | Performance ↑ from 200–400; 400–5000 equivalent | Advanced Bionic, Cochlear |

| Best performance at higher rate | |||||

| 2000 | Kiefer et al. [37] | 13 | 600/1500–1730 | Best performance at highest rate | MED-EL |

| 2000 | Loizou et al. [14] | 6 | 400/800/1400/2100 | Better performance at 2100 vs. <800 | MED-EL |

| 2002 | Holden et al. [13] | 8 | 720/1800 | Best performance at highest rate for speech in noise | Cochlear |

| 2002 | Psarros et al. [39] | 7 | 250/900 | Best performance at highest rate | Cochlear |

| 2003 | Au [34] | 11 | 400/800/1800 | Best performance at highest rate | MED-EL |

| 2003 | Frijns et al. [36] | 9 | 833/1400 | Better performance at highest rate for speech in noise | Advanced Bionic |

| 2006 | Nie et al. [38] | 5 | 1000–4000 | Best performance at highest rate | MED-EL |

| 2009 | Arora et al. [33] | 8 | 275/350/500/900 | Best performance at 500/900 for speech in noise | Cochlear |

| 2010 | Buechner et al. [11] | 13 | 1500–5000 | Some users did best at medium fast rates of 2500/3000, whereas some users performed best at the highest rate 5000 | Advanced Bionic |

| 2010 | Di Lella et al. [35] | 10 | 260/600 | Best performance at highest rate in quiet and in noise | Oticon (Neurelec) |

| 2011 | Shannon et al. [41] | 7 | 600/1200/2400/4800 | Small effect (4800 > 600) | Advanced Bionic |

| 2016 | Riss et al. [40] | 26 | 750/1376 | Best performance at highest rate | Med-El |

| Best performance at lower rate | |||||

| 2000 | Vandali et al. [16] | 5 | 250/807/1615 | No difference between 250/807; poorer at 1615 (mostly due to the results of one CI user). | Cochlear |

| 2012 | Park et al. [47] | 6 | 900/2400 | Better performance at lowest rate | Cochlear |

| 2019 | Shader et al. [48] | 37 | 500/720/900/1200/ >1200 | Some users performed best at lower-than-default rate | Advanced Bionic, Cochlear, MED-EL |

| No effect | |||||

| 2005 | Verschuur [46] | 6 | 400/800/1500–2020 | No significant effect of rate * | MED-EL |

| 2007 | Balkany [10] | 71 | 500–3500 | No effect | Cochlear |

| 2007 | Plant et al. [31] | 15 | 1200/2400 or 3500 | No significant effect * | Cochlear |

| 2012 | Bonnet et al. [44] | 27 | 774/967/1289/1934/3868 | No effect | Advanced Bionic |

| 2022 | Kovačić and James [45] | 16 | 250/500/1000 | No effect | Cochlear |

| 2023 | Berg et al. [49] | 7 | 600/1200/1245–4800 | No significant improvements with higher rates | Advanced Bionic |

| 2025 | Arora et al. [9] | 18 | 500/900 | No effect | Cochlear |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sharp, A.; Beaudoin, D.; Dufour, J.; Bacon, B.-A.; Champoux, F. Questioning the Usefulness of Stimulation Rate Changes to Optimize Perception in Cochlear Implant Users. Audiol. Res. 2026, 16, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010006

Sharp A, Beaudoin D, Dufour J, Bacon B-A, Champoux F. Questioning the Usefulness of Stimulation Rate Changes to Optimize Perception in Cochlear Implant Users. Audiology Research. 2026; 16(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharp, Andreanne, Daniel Beaudoin, Julie Dufour, Benoit-Antoine Bacon, and François Champoux. 2026. "Questioning the Usefulness of Stimulation Rate Changes to Optimize Perception in Cochlear Implant Users" Audiology Research 16, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010006

APA StyleSharp, A., Beaudoin, D., Dufour, J., Bacon, B.-A., & Champoux, F. (2026). Questioning the Usefulness of Stimulation Rate Changes to Optimize Perception in Cochlear Implant Users. Audiology Research, 16(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010006