Exploring the Effects of Attribute Framing and Popularity Cueing on Hearing Aid Purchase Likelihood

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Nudge Theory and Decision-Making

1.2. Message Framing in Hearing Aid Marketing

1.3. Social Norm Messaging and Popularity Cues

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

2.2. Procedure and Experimental Manipulation

2.2.1. Study Recruitment and Platform

2.2.2. Decision-Making Scenarios

2.2.3. Experimental Manipulations

2.3. Experimental Measures

2.3.1. Purchase Likelihood Ratings

2.3.2. Additional Opinion Measures

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Information

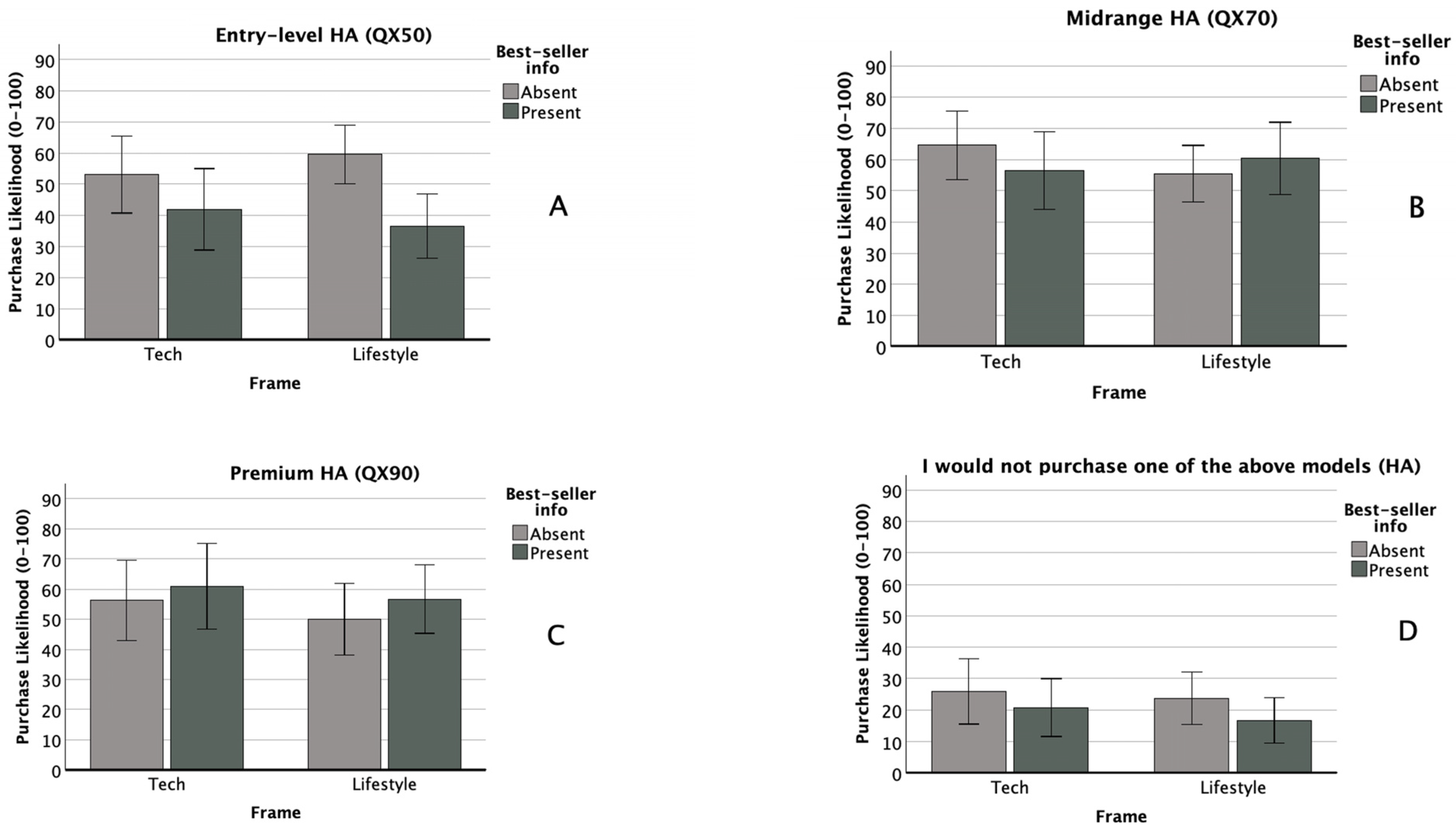

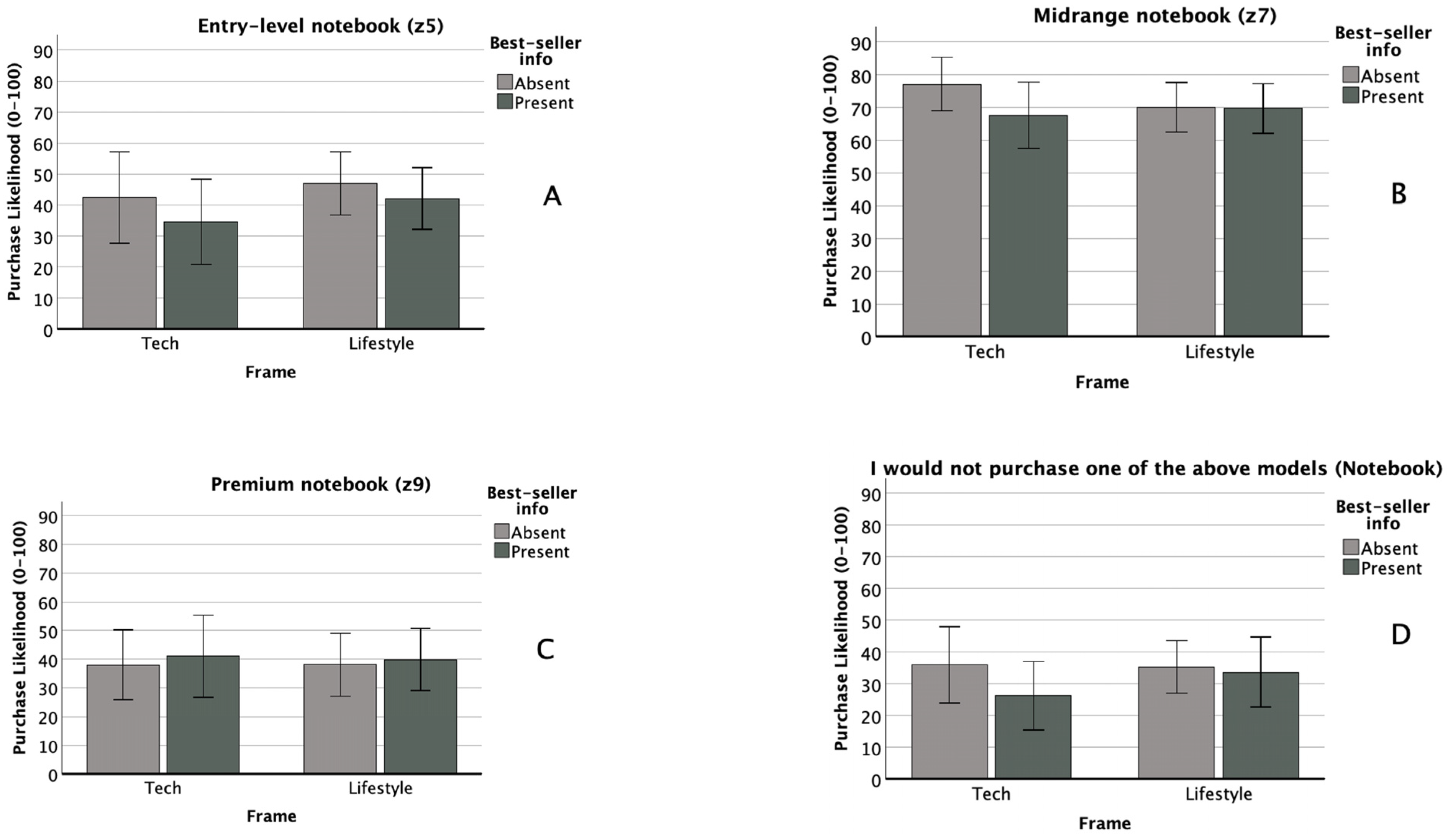

3.2. Main and Interaction Effects of Framing and Popularity Cueing

3.2.1. Entry-Level (QX50 HA, z5 Notebook)

3.2.2. Midrange (QX70 HA, z7 Notebook)

3.2.3. Premium (QX90 HA, z9 Notebook)

3.2.4. I Would Not Purchase Any of the Above Models (HA and Notebook)

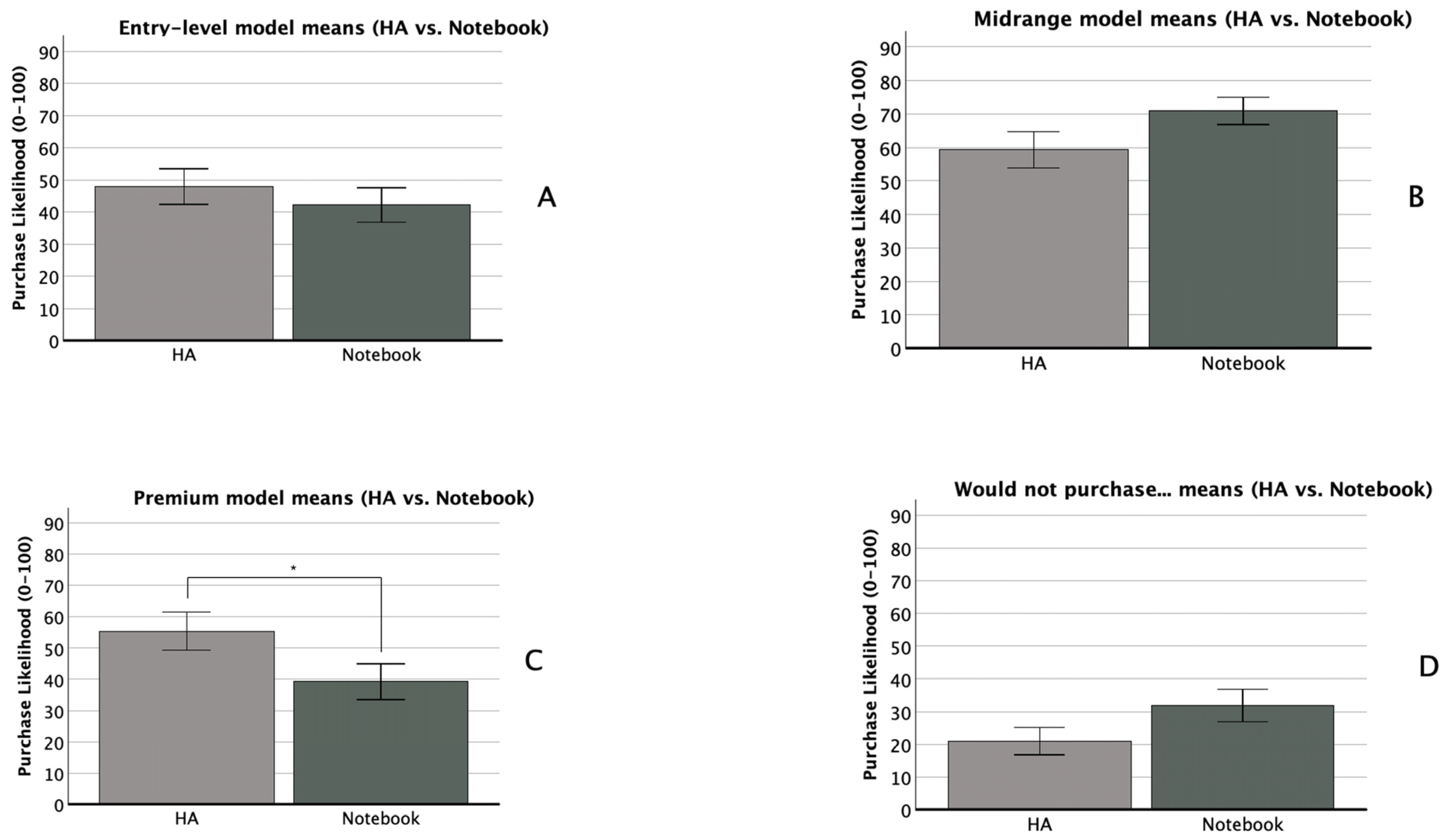

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Popularity Cueing on HA Purchase Likelihood

4.1.1. Why Did Popularity Cueing Reduce Interest in the Entry-Level HA?

4.1.2. Why Did the Popularity Cue Not Increase Midrange HA Purchase Likelihood?

4.1.3. Why Did the Popularity Cue Not Affect the Premium HA?

4.2. Effect of Attribute Framing on HA Purchase Likelihood

Why Was There No Meaningful Effect of Lifestyle vs. Technology Framing?

4.3. HAs vs. Notebook Computers

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HA | Hearing Aids |

| OTC | Over the counter |

References

- Jorgensen, L.; Novak, M. Factors influencing hearing aid adoption. Semin. Hear. 2020, 41, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, C.R.; Barker, B.A.; Scharp, K.M. Using attribution theory to explore the reasons adults with hearing loss do not use their hearing aids. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, M.; Willink, A.; McMahon, C.; McPherson, B.; Nieman, C.L.; Reed, N.S.; Lin, F.R. Access to adults’ hearing aids: Policies and technologies used in eight countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostevik, A.V.; Westover, L.; Gynane, H.; Herst, J.; Cummine, J.; Hodgetts, W.E. Comparison of health insurance coverage for hearing aids and other services in Alberta. Healthc. Policy 2019, 15, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iankilevitch, M.; Singh, G.; Russo, F.A. A scoping review and field guide of theoretical approaches and recommendations to studying the decision to adopt hearing aids. Ear Hear. 2023, 44, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Junghans, A.F.; Cheung, T.T.; De Ridder, D.D. Under consumers’ scrutiny: An investigation into consumers’ attitudes and concerns about nudging in the realm of health behavior. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raban, M.Z.; Gonzalez, G.; Nguyen, A.D.; Newell, B.R.; Li, L.; Seaman, K.L.; Westbrook, J.I. Nudge interventions to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing in primary care: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e062688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P.G.; Jespersen, A.M. Nudge and the manipulation of choice: A framework for the responsible use of the nudge approach to behaviour change in public policy. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2013, 4, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroese, F.M.; Marchiori, D.R.; De Ridder, D.T. Nudging healthy food choices: A field experiment at the train station. J. Public Health 2016, 38, e133–e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, C.R.S.; Cummine, J.; Singh, G.; Hodgetts, W.E. Be part of the conversation: Audiology messaging during a hearing screening. Ear Hear. 2021, 42, 1680–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgetts, B.; Ostevik, A.; Aalto, D.; Cummine, J. Don’t fade into the background: A randomized trial exploring the effects of message framing in audiology. Can. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. Audiol. 2017, 41, 175–202. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruijn, G.J.; Spaans, P.; Jansen, B.; van’t Riet, J. Testing the effects of a message framing intervention on intentions towards hearing loss prevention in adolescents. Health Educ. Res. 2016, 31, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheufele, D.A.; Iyengar, S. The state of framing research: A call for new directions. In Oxford Handbook of Political Communication Theories; Kenski, K., Jamieson, K.H., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amlani, A.M.; Taylor, B.; Weinberg, T. Increasing hearing aid adoption rates through value-based advertising and price unbundling. Hear. Rev. 2011, 18, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Adorni, R.; Manzi, C.; Crapolicchio, E.; Steca, P. The role of the family doctor’s language in modulating people’s attitudes towards hearing loss and hearing aids. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e1775–e1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, C.; Adorni, R.; Di Cicco, G.; Milano, V.; Manunta, E.; Montermini, F.; Steca, P. Implicit and explicit attitudes toward hearing aids: The role of media language. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 41, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, N.; Shulman, H.C.; McClaran, N. Changing norms: A meta-analytic integration of research on social norms appeals. Hum. Commun. Res. 2020, 46, 161–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, A.J.; Shavitt, S. Top rated or best seller? Cultural differences in responses to attitudinal versus behavioral consensus cues. J. Consum. Res. 2024, 51, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiassaleh, A.; Kocher, B.; Czellar, S. Best seller!? Unintended negative consequences of popularity signs on consumer choice behavior. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 37, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchaiah, V.; Portnuff, C.; Sharma, A.; Swanepoel, D.W. Over-the-counter hearing aids: What do consumers need to know? Hear. J. 2023, 76, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plyler, P.N.; Hausladen, J.; Capps, M.; Cox, M.A. Effect of hearing aid technology level and individual characteristics on listener outcome measures. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2021, 64, 3317–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amlani, A.M. Application of the consumer decision-making model to hearing aid adoption in first-time users. Semin. Hear. 2016, 37, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schwartz, B. The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less; HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar, R.; Simonson, I. The effect of forced choice on choice. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, J.B.; Vedlitz, A. Emphasis framing and the role of perceived knowledge: A survey experiment. Rev. Policy Res. 2017, 34, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.G.; Sar, S.; Ghuge, S. The moderating role of mood and personal relevance on persuasive effects of gain- and loss-framed health messages. Health Mark. Q. 2015, 32, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Hickson, L. What factors influence help-seeking for hearing impairment and hearing aid adoption in older adults? Int. J. Audiol. 2012, 51, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, A.W.; Craig, S.B. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonson, I. Choice based on reasons: The case of attraction and compromise effects. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Wang, A.; Wang, C.; Ma, Q. How do consumers perceive and process online overall vs. individual text-based reviews? Behavioral and eye-tracking evidence. Inf. Manag. 2023, 60, 103795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 363–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, K.; Michaud, D.; Ramage-Morin, P.; McNamee, J.; Beauregard, Y. Prevalence of hearing loss among Canadians aged 20 to 79: Audiometric results from the 2012/2013 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Health Rep. 2015, 26, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jilla, A.M.; Jorgsensen, L. Hearing aid adoption in the OTC hearing aid era: Market trends and consumer insight from MarkeTrak 2025. Semin. Hear. 2025, 46, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picou, E.M.; Huang, H. Are Over-the-Counter hearing aids affordable, accessible, and satisfactory? Insights from MarkeTrak 25 survey data. Semin. Hear. 2025, 46, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobyan, B.; Kihm, J. MarkeTrak 2025: Consumer perspectives on hearing health in an evolving market. Semin. Hear. 2025, 46, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Description | Features | Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| QX50 | The QX50 will help you hear better and will allow you to more easily enjoy sound in your daily life. For instance, the radio in your car and conversations with friends will sound louder and crisper. Feedback cancellation minimizes distracting noises, allowing you to focus on the sounds you want to hear. |

| CAD 1900 |

| QX70 | The QX70 is designed with your connected life in mind. Smart device streaming lets you answer phone calls and enjoy the sound from your favorite TV shows directly through your hearing aid. The QX70 is also adjustable via an app, allowing you to customize your listening settings to suit your preferences. |

| CAD 2600 |

| QX90 | The QX90 is the most advanced device, and will help you hear your best in the widest range of today’s situations. The Mask Mode and StereoZoom features are designed with noisy and physically-distanced environments in mind, allowing you to continue hearing as clearly as possible in challenging situations. These features also help reduce the effort it takes when you’re trying to listen in these environments. |

| CAD 3300 |

| Model | Description | Features | Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| z5 | Whether you’re zipping across town or Zooming from your bedroom, the z5 offers maximum portability (weighing in at just 900 g!) without sacrificing the performance you require. Built for entertainment and basic work/study needs, this unit is ideal for staying connected on the go. |

| CAD 1399 |

| z7 | The z7 strikes a sweet spot for work, play, and everything in between. At an even 1000 g, this 13-inch unit is ideal at your work desk, kitchen table, or your favorite comfy spot in the living room. Its Touch ID feature makes privacy faster and easier than ever. |

| CAD 1699 |

| z9 | You’ve never seen portability this powerful! The z9 packs features for every lifestyle into a unit the weight of your water bottle. Its full-day’s worth of battery life ensures you’ll never be caught without a charge. With top-of-the-line connectivity, processing, and security features, the z9 is the ultimate notebook for your connected life. |

| CAD 2199 |

| Model | Description | Features | Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| QX50 | The QX50 will help boost the signal the ear receives. The key feature is a directional microphone, which makes the target signal louder than the background noise. This device also comes with feedback cancellation to minimize squeaking sounds from the device that sometimes happen with hearing aids. |

| CAD 1900 |

| QX70 | The QX70 includes all the features of the QX50 and offers the extra benefit of audio streaming with smart devices, like phones or TVs. Additionally, the QX70 is compatible with an iPhone/Android app that allows the device to be adjusted comfortably in various listening settings. |

| CAD 2600 |

| QX90 | The QX90 offers the most advanced functionality. Including all the features of the QX70, this model also introduces Mask Mode and StereoZoom. Mask Mode uses artificial intelligence to boost speech clarity in difficult listening situations. StereoZoom makes it easier for the ear to differentiate between speech coming from multiple directions by focusing on target sounds. |

| CAD 3300 |

| Model | Description | Features | Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| z5 | At only 900 g, the z5 offers impressive processing power and battery life for its small size. Its 4-core processor outperforms comparably-sized models on the market, while its 2 TBs of storage far surpasses the storage capacity of other mini-notebooks. |

| CAD 1399 |

| z7 | The standard-sized z7 maintains a light weight and ease of portability while presenting a significant upgrade in all other major features: longer battery life, faster processing, and increased storage. It also comes equipped with a Touch Bar and Touch ID, features which represent market leading advancements in accessibility and privacy. |

| CAD 1699 |

| z9 | With a 15-inch Retina display, this is the largest model in the z-line, and by far the most powerful. With double the capacity and performance of the z7, the z9’s additionally offers compatibility with Wifi 6 and 5G mobile broadband, altogether representing the cutting edge in notebook computing. |

| CAD 2199 |

| Characteristic | Category | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest level of education completed | High school | 1 | 0.8 |

| Trade/technical/vocational | 7 | 5.7 | |

| Some university/college | 18 | 14.7 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 45 | 36.9 | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 51 | 41.8 | |

| Employment status | Employed part-time | 11 | 9.0 |

| Employed full-time | 79 | 64.8 | |

| Retired | 10 | 8.2 | |

| Student | 16 | 13.1 | |

| Unable to work | 3 | 2.5 | |

| Unemployed | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Other | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Marital status | Single | 18 | 14.8 |

| Married (or Common Law) | 86 | 70.5 | |

| Separated | 5 | 4.1 | |

| Divorced | 13 | 10.7 | |

| Household income (in Canadian dollars) | Under CAD 25,000 | 7 | 5.7 |

| CAD 25,000–CAD 39,999 | 5 | 4.1 | |

| CAD 40,000–CAD 49,999 | 2 | 1.6 | |

| CAD 50,000–CAD 74,999 | 14 | 11.5 | |

| CAD 75,000–CAD 99,999 | 27 | 22.1 | |

| Over CAD 100,000 | 67 | 54.9 | |

| Currently using or ever used HAs | No | 116 | 95.1 |

| Yes | 6 | 4.9 |

| HA Model | Condition | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QX50 | Tech/No cue | 23 | 53.04 | 28.51 |

| Tech/Cue | 25 | 41.92 | 31.58 | |

| Lifestyle/No cue | 38 | 59.55 | 28.63 | |

| Lifestyle/Cue | 36 | 36.33 | 30.26 | |

| QX70 | Tech/No cue | 22 | 64.50 | 26.12 |

| Tech/Cue | 22 | 57.09 | 31.38 | |

| Lifestyle/No cue | 35 | 55.54 | 27.67 | |

| Lifestyle/Cue | 34 | 61.18 | 33.23 | |

| QX90 | Tech/No cue | 23 | 56.22 | 30.83 |

| Tech/Cue | 25 | 60.96 | 34.42 | |

| Lifestyle/No cue | 38 | 49.97 | 36.36 | |

| Lifestyle/Cue | 36 | 56.67 | 33.61 | |

| Would not purchase | Tech/No cue | 22 | 28.46 | 26.98 |

| Tech/Cue | 22 | 21.36 | 21.99 | |

| Lifestyle/No cue | 36 | 25.00 | 26.60 | |

| Lifestyle/Cue | 36 | 20.47 | 25.32 | |

| Notebook model | Condition | N | Mean | SD |

| z5 | Tech/No cue | 23 | 42.39 | 34.09 |

| Tech/Cue | 25 | 34.56 | 33.32 | |

| Lifestyle/No cue | 38 | 47.00 | 31.32 | |

| Lifestyle/Cue | 36 | 42.11 | 29.43 | |

| z7 | Tech/No cue | 22 | 77.18 | 18.43 |

| Tech/Cue | 22 | 67.64 | 22.85 | |

| Lifestyle/No cue | 35 | 70.06 | 22.15 | |

| Lifestyle/Cue | 34 | 69.74 | 21.66 | |

| z9 | Tech/No cue | 23 | 38.04 | 28.18 |

| Tech/Cue | 25 | 41.08 | 34.81 | |

| Lifestyle/No cue | 38 | 38.08 | 33.47 | |

| Lifestyle/Cue | 36 | 39.89 | 32.10 | |

| Would not purchase | Tech/No cue | 22 | 36.00 | 27.08 |

| Tech/Cue | 22 | 26.32 | 24.43 | |

| Lifestyle/No cue | 36 | 35.31 | 24.44 | |

| Lifestyle/Cue | 36 | 33.72 | 32.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

St. Jean, C.R.; Cummine, J.; Singh, G.; Hodgetts, W. Exploring the Effects of Attribute Framing and Popularity Cueing on Hearing Aid Purchase Likelihood. Audiol. Res. 2026, 16, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010012

St. Jean CR, Cummine J, Singh G, Hodgetts W. Exploring the Effects of Attribute Framing and Popularity Cueing on Hearing Aid Purchase Likelihood. Audiology Research. 2026; 16(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleSt. Jean, Craig Richard, Jacqueline Cummine, Gurjit Singh, and William (Bill) Hodgetts. 2026. "Exploring the Effects of Attribute Framing and Popularity Cueing on Hearing Aid Purchase Likelihood" Audiology Research 16, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010012

APA StyleSt. Jean, C. R., Cummine, J., Singh, G., & Hodgetts, W. (2026). Exploring the Effects of Attribute Framing and Popularity Cueing on Hearing Aid Purchase Likelihood. Audiology Research, 16(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010012