Cochlear Implants and Adult Patient Experiences, Adaptation and Challenges: A Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Questionnaire

- Demographic data (age, gender, education, employment status);

- Pre-implantation experiences (duration of hearing loss, referral process, time to decision-making, and influencing factors);

- Surgical outcomes (device type, implant type, and subjective perspectives on outcomes);

- Post-implantation experiences (duration of use, psychosocial impact, and satisfaction with the implant).

2.2. Sample Size and Sampling Method

- Adults aged 18 years and above at the time of first CI.

- Current users of CIs.

- Active patients at one of the three participating hospitals.

- Individuals below 18 years of age.

- Non-users of CI.

- Patients who were no longer receiving care from the participating hospitals.

- Survey forms with incomplete demographic information.

- Inconsistent responses across the survey.

- Unverified consent.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Patients

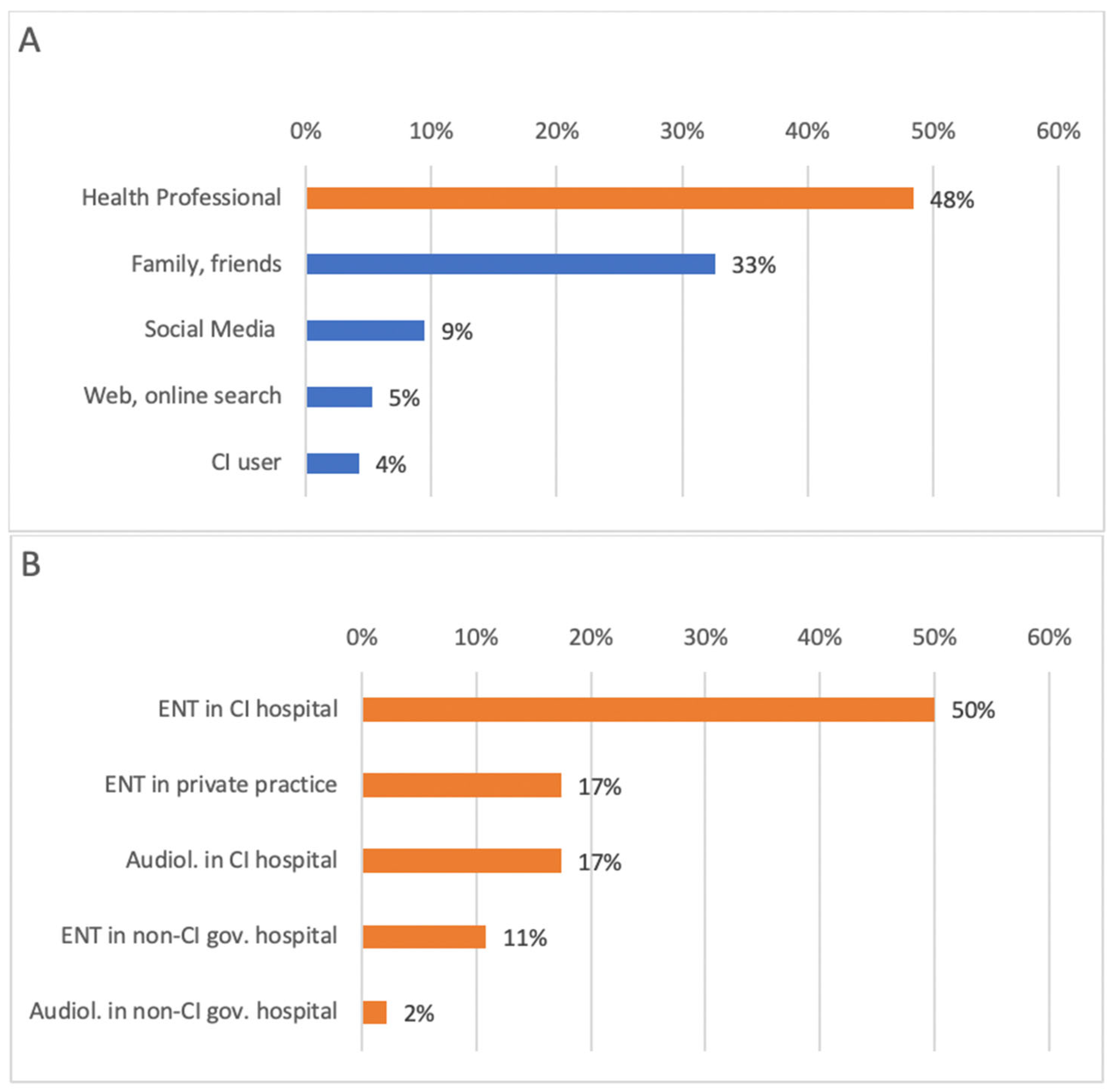

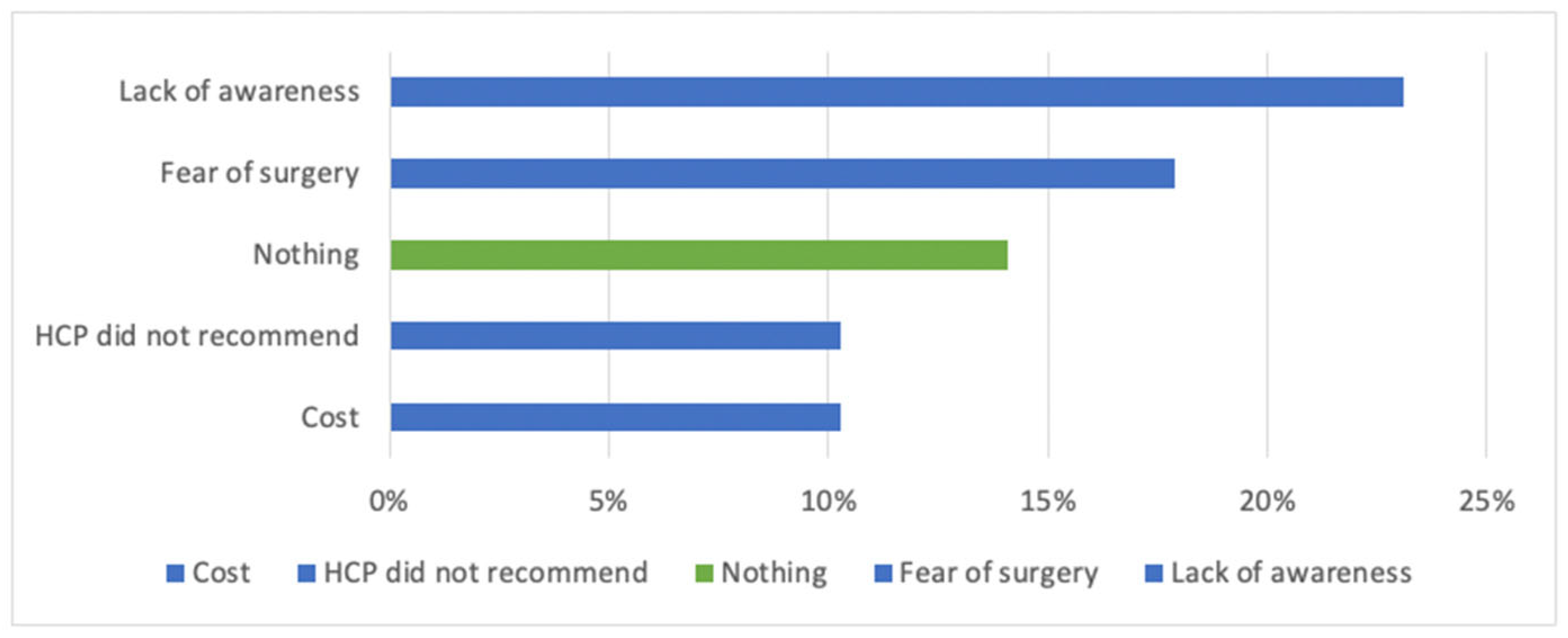

3.2. Awareness and Access Barriers to CI

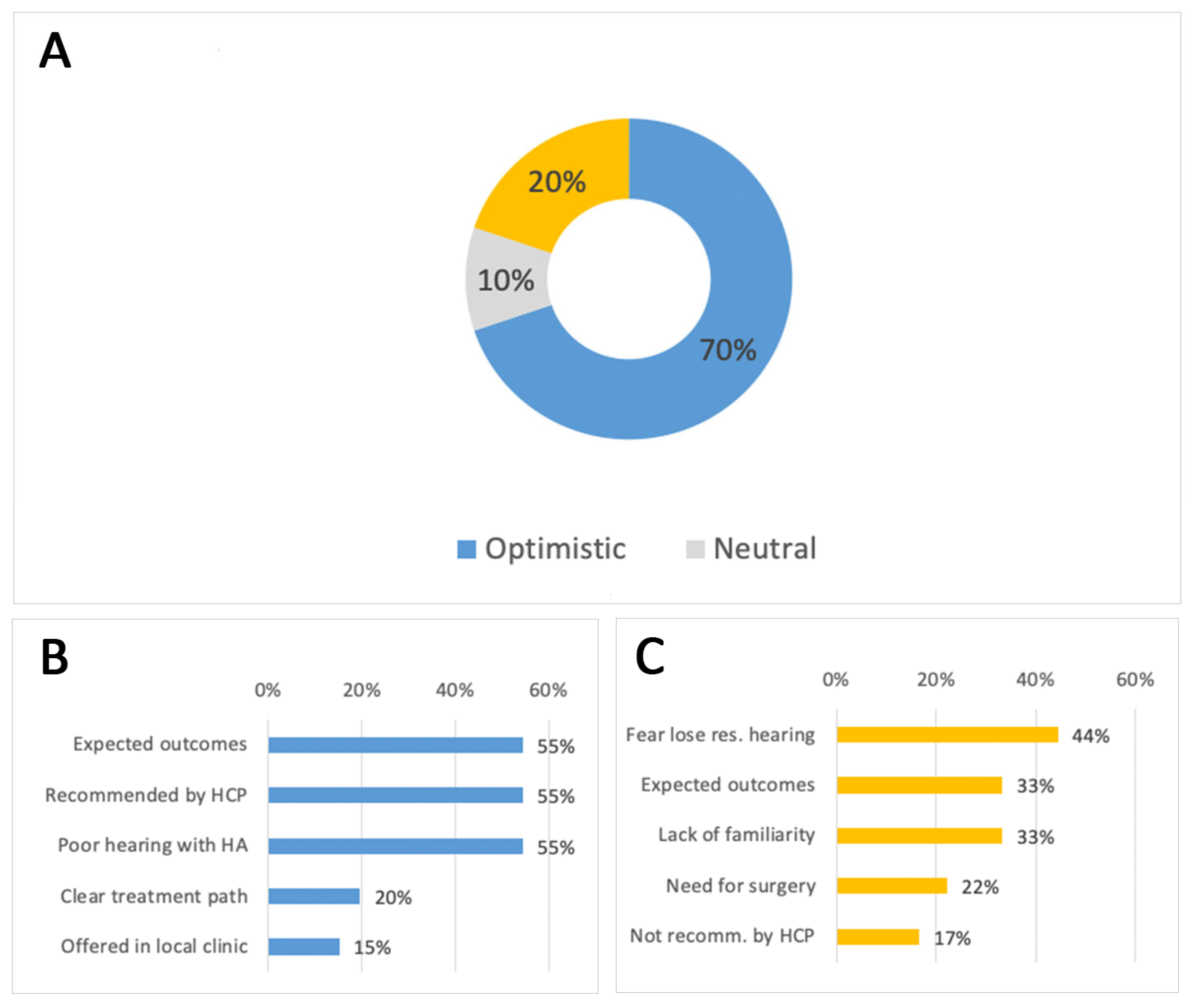

3.3. Candidate Attitudes Toward CI

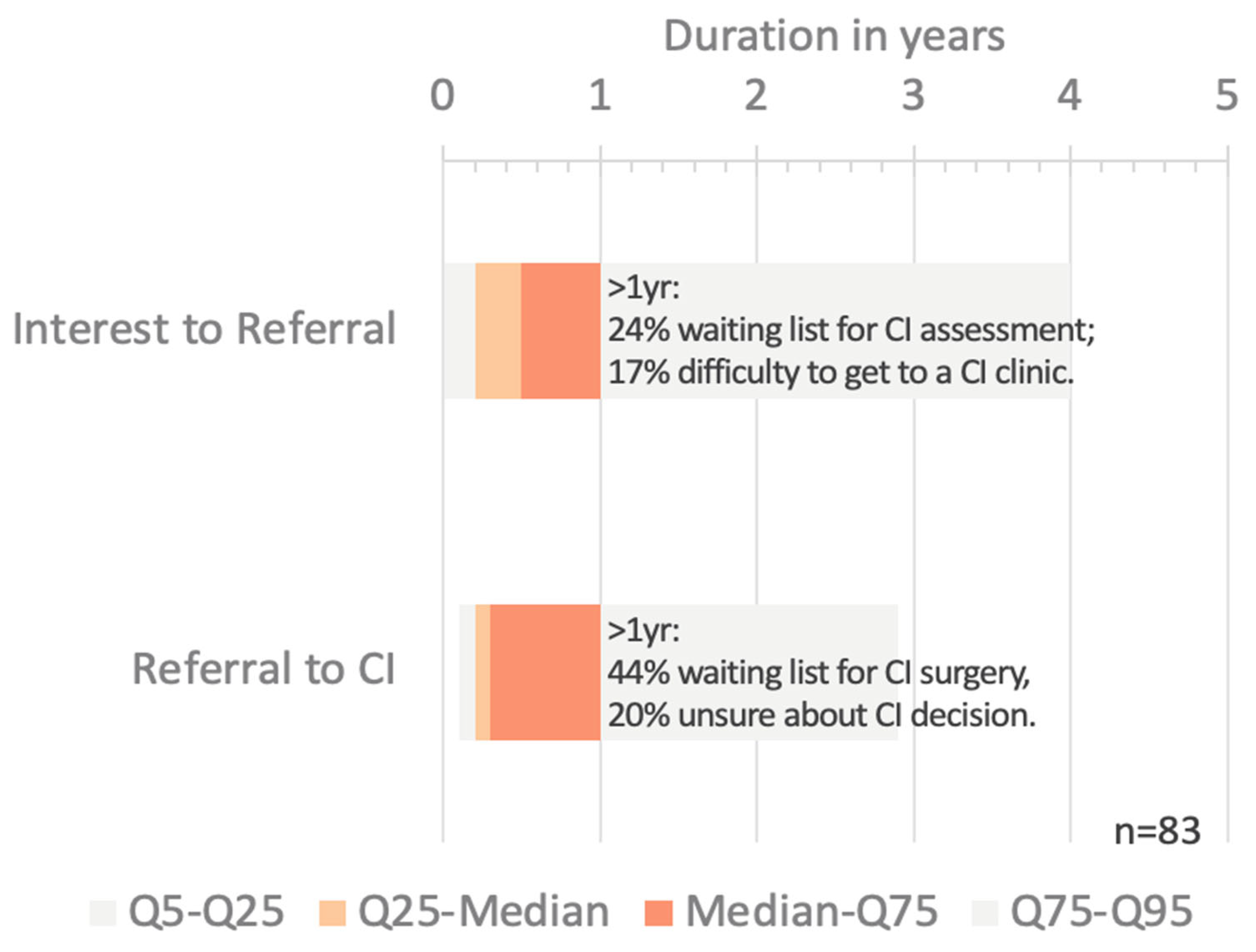

3.4. Delays on the Path to Treatment

3.5. Device Choice

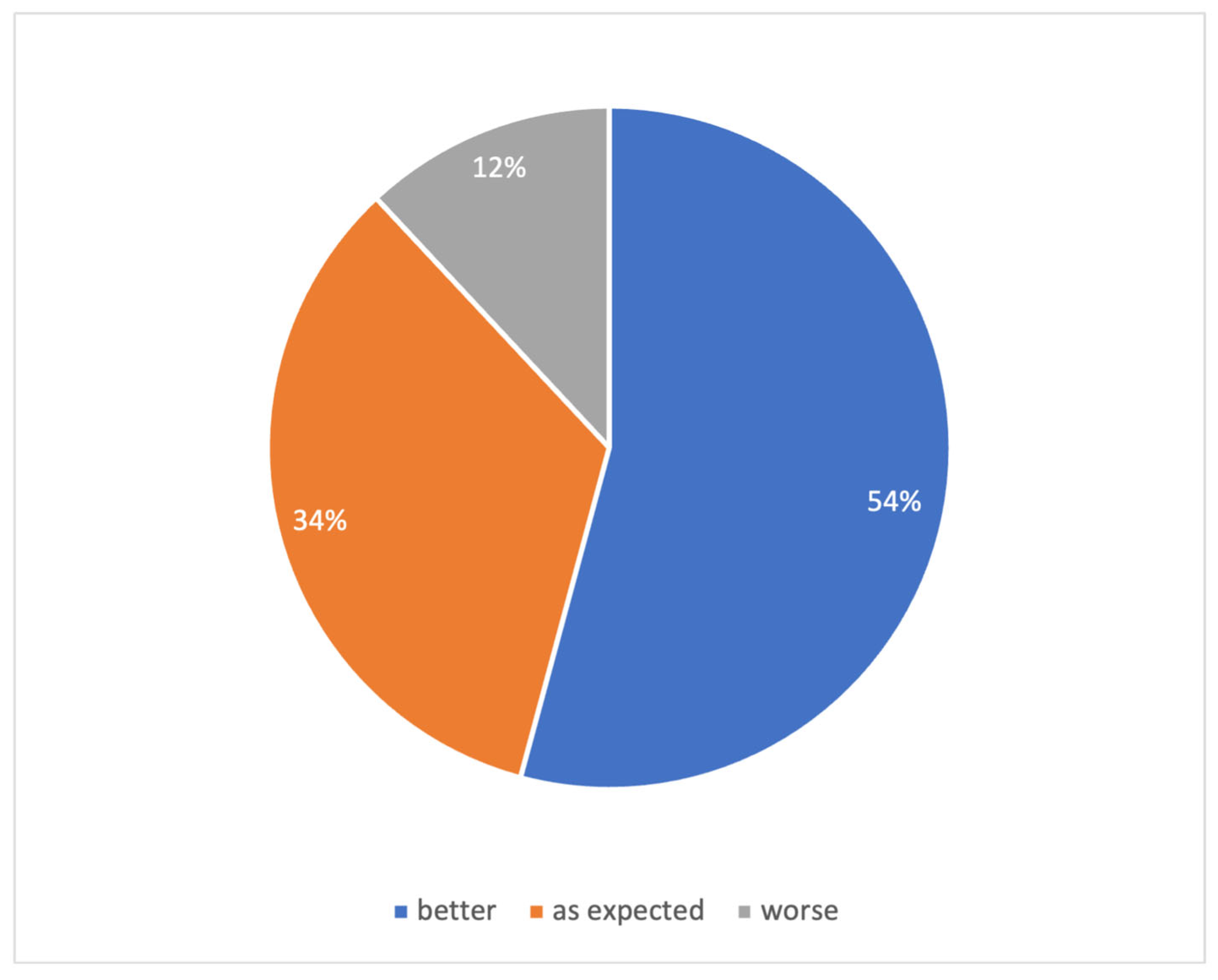

3.6. Post-Implantation Perspectives

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| APC | Article Processing Charge |

| CI | Cochlear Implant |

| CIQOL-36 | Cochlear Implant Quality of Life-36 |

| dB HL | Decibels Hearing Level |

| ERKI | Erfassung des Richtungshörens bei Kindern (Localization Testing in Children) |

| HCP | Health Care Professional |

| ILD | Interaural Level Difference |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| KACST | King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology |

| KSA | Kingdom of Saudi Arabia |

| LED | Light-Emitting Diode |

| LT | Left (ear) |

| ORCID | Open Researcher and Contributor ID |

| RT | Right (ear) |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SPL | Sound Pressure Level |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Sun, Y.; Yi, Y.; Huang, G.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, D. Temporal trends in prevalence and years of life lived with disability for hearing loss in China from 1990 to 2021: An analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1538145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Challenges Facing Ear and Hearing Care. In World Report on Hearing; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 139–198. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss#:~:text=Over%205%25%20of%20the%20world's,affected%20by%20disabling%20hearing%20loss (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- World Report on Hearing Executive Summary. 2021. Available online: http://apps.who.int/bookorders (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Malcolm, K.A.; Suen, J.J.; Nieman, C.L. Socioeconomic position and hearing loss: Current understanding and recent advances. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 30, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieu, J.E.C.; Tye-Murray, N.; Karzon, R.K.; Piccirillo, J.F. Unilateral Hearing Loss is Associated with Worse Speech-language Scores in Children: A Case-Control Study. Pediatrics 2010, 125, e1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcar-Gozalbo, N.; López-Zamora, M.; Valles-González, B.; Cano-Villagrasa, A. Impact of Hearing Loss Type on Linguistic Development in Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. Audiol. Res. 2024, 14, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Chern, A.; Golub, J.S. Age-Related Hearing Loss and the Development of Cognitive Impairment and Late-Life Depression: A Scoping Overview. Semin. Hear. 2021, 42, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.-Y.; Han, K.; Yang, F.; Yin, S.-Y.; Zhang, L.; Liang, B.-Y.; Wang, T.-B.; Jiang, T.; Chen, Y.-R.; Shi, T.-Y.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of hearing loss from 1990 to 2019: A trend and health inequality analyses based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 92, 102124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basura, G.; Cienkowski, K.; Hamlin, L.; Ray, C.; Rutherford, C.; Stamper, G.; Schooling, T.; Ambrose, J. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Clinical Practice Guideline on Aural Rehabilitation for Adults with Hearing Loss. Am. J. Audiol. 2023, 32, 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bittencourt, A.G.; Torre AAGDella Bento, R.F.; Tsuji, R.K.; De Brito, R. Prelingual deafness: Benefits from cochlear implants versus conventional hearing aids. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2012, 16, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitler, D.M.; Prentiss, S.M.; Sydlowski, S.A.; Dunn, C.C. American Cochlear Implant Alliance Task Force: Recommendations for Determining Cochlear Implant Candidacy in Adults. Laryngoscope 2024, 134 (Suppl. S3), S1–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchman, C.A.; Gifford, R.H.; Haynes, D.S.; Lenarz, T.; O’Donoghue, G.; Adunka, O.; Biever, A.; Briggs, R.J.; Carlson, M.L.; Dai, P.; et al. Unilateral Cochlear Implants for Severe, Profound, or Moderate Sloping to Profound Bilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review and Consensus Statements. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 146, 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijmeijer, H.G.B.; Keijsers, N.M.; Huinck, W.J.; Mylanus, E.A.M. The effect of cochlear implantation on autonomy, participation and work in postlingually deafened adults: A scoping review. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2020, 278, 3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbie, M.; Olin, E.; Parkinson, B.; Bowman, R.; Cutler, H. The cost-effectiveness of Cochlear implants in Swedish adults. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadie, R.F.; Carrasco, V.N.; Gilmer, C.H.; Pillsbury, H.C. Cochlear implant performance in senior citizens. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2000, 123, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dornhoffer, J.R.; Reddy, P.; Ma, C.; Schvartz-Leyzac, K.C.; Dubno, J.R.; Mcrackan, T.R. Use of Auditory Training and Its Influence on Early Cochlear Implant Outcomes in Adults. Otol. Neurotol. 2022, 46, e450–e452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Völter, C.; Götze, L.; Haubitz, I.; Dazert, S.; Thomas, J.P. Benefits of Cochlear Implantation in Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2020, 15, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassiri, A.M.; Marinelli, J.P.; Sorkin, D.L.; Carlson, M.L. Barriers to Adult Cochlear Implant Care in the United States: An Analysis of Health Care Delivery. Semin. Hear. 2021, 42, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Macías, Á.; De Raeve, L.; Holcomb, M.; Connor, E.; Taylor, A.; Deltetto, I.; Taylor, C. Strategies for the implementation of the living guidelines for cochlear implantation in adults. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1272437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swords, C.; Ghedia, R.; Blanchford, H.; Arwyn–Jones, J.; Heward, E.; Milinis, K.; Hardman, J.; Smith, M.E.; Bance, M.; Muzaffar, J.; et al. Socioeconomic and ethnic disparities associated with access to cochlear implantation for severe-to-profound hearing loss: A multicentre observational study of UK adults. PLoS Med. 2024, 21, e1004296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badreldin, H.A.; Al-jedai, A.; Alghnam, S.; Nakshabandi, Z.; Alharbi, M.; Alzahrani, A.; Alqadri, H.; Almodeiheem, H.; Alhazmi, R.; Althumairi, A.; et al. Sustainability and Resilience in the Saudi Arabian Health System SAUDI ARABIA. 2025. Available online: https://www.phssr.org (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Karlin, N.J.; Weil, J.; Felmban, W. Aging in Saudi Arabia: An Exploratory Study of Contemporary Older Persons’ Views About Daily Life, Health, and the Experience of Aging. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2016, 2, 2333721415623911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwisle, L.K.; Warren, S.E.; Messersmith, J.J. Cochlear Implantation for Children and Adults with Severe-to-Profound Hearing Loss. Semin. Hear. 2018, 39, 390. [Google Scholar]

- De Raeve, L.; Archbold, S.; Lehnhardt-Goriany, M.; Kemp, T. Prevalence of cochlear implants in Europe: Trend between 2010 and 2016. Cochlear Implant Int. 2020, 21, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contrera, K.J.; Choi, J.S.; Blake, C.R.; Betz, J.F.; Niparko, J.K.; Lin, F.R. Rates of Long-Term Cochlear Implant Use in Children. Otol. Neurotol. 2014, 35, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberberg, M.; Singh, A.; Bettger, J.P.; Smith, S.L.; Francis, H.W.; Dubno, J.R.; Schulz, K.A.; Dolor, R.J.; Walker, A.R.; Tucci, D.L. Routine Hearing Screening for Older Adults in Primary Care: Insights of Patients and Clinic Personnel. Gerontologist 2024, 64, gnae107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neukam, J.D.; Kunnath, A.J.; Patro, A.; Gifford, R.H.; Haynes, D.S.; Moberly, A.C.; Tamati, T.N. Barriers to Cochlear Implant Uptake in Adults: A Scoping Review. Otol. Neurotol. 2024, 45, e679–e686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al, F.A.; Fam, A. Neonatal Services Improvement Program, Deputyship for therapeutic services. J. Pediatr. Neonatal Med. 2021, 3, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzone, C.; Guerzoni, L.; Ghiselli, S.; Franchomme, L.; Nicastri, M.; Mancini, P.; Fabrizi, E.; Cuda, D. Early Cochlear Implant Promotes Global Development in Children with Severe-to-Profound Hearing Loss. Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, M.A.; Aldajani, N.F.; Alghamdi, S.A. Guidelines for cochlear implantation in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2021, 42, 1265–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindhim, N.F.; Senitan, M.; Almutairi, M.N.; Alhadlaq, L.S.; Alnajem, S.A.; Alfaifi, M.A.; Althumiri, N.A. Demographic, health, and behaviors profile of Saudi Arabia’s aging population 2022–2023. Front. Aging 2025, 6, 1491146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Q.; Reilly, B.K.; Preciado, D.A. Barriers to pediatric cochlear implantation: A parental survey. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 104, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettman, S.; Choo, D.; Dowell, R. Barriers to early cochlear implantation. Int. J. Audiol. 2016, 55 (Suppl. S2), S64–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chundu, S.; Buhagiar, R. Audiologists’ knowledge of cochlear implants and their related referrals to the cochlear implant centre: Pilot study findings from UK. Cochlear Implant. Int. 2013, 14, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisoni, D.B.; Kronenberger, W.G.; Harris, M.S.; Moberly, A.C. Three challenges for future research on cochlear implants. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 3, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Kheir, D.Y.M.; Boumarah, D.N.; Bukhamseen, F.M.; Masoudi, J.H.; Boubshait, L.A. The Saudi Experience of Health-Related Social Media Use: A Scoping Review. Saudi J. Health Syst. Res. 2021, 1, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSadrah, S.A. Social media use for public health promotion in the Gulf Cooperation Council: An overview. Saudi Med. J. 2021, 42, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.J.; Yu, M.; Leong, S.; Chern, A. Exploration and Analysis of Cochlear Implant Content on Social Media. Cureus 2023, 15, e45801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hixon, B.; Chan, S.; Adkins, M.; Shinn, J.B.; Bush, M.L. Timing and Impact of Hearing Healthcare in Adult Cochlear Implant Recipients: A Rural-Urban Comparison. Otol. Neurotol. 2016, 37, 1320–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalil, R.H.; Al-Sowayan, B.S.; Albdah, B. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rehabilitation services provided for cochlear implant recipients in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabie, J.E.; Shannon, C.M.; Chidarala, S.; Schvartz-Leyzac, K.; Camposeo, E.L.; Dubno, J.R.; McRackan, T.R. Changes in Outcomes Expectations During the Cochlear Implant Evaluation Process. Ear Hear. 2025, 46, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, B.; Pryce, H. What makes someone choose cochlear implantation? An exploration of factors that inform patient decision making. Int. J. Audiol. 2020, 59, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadège, C.; Valérie, G.; Laura, F.; Hélène, D.B.; Vanina, B.; Olivier, D.; Bernard, F.; Laurent, M. The Cost of Cochlear Implantation: A Review of Methodological Considerations. Int. J. Otolaryngol. 2011, 2011, 210838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochlear Implants Market—Market Size, Sustainable Insights and Growth Report 2025–2032. Available online: https://www.datamintelligence.com/research-report/cochlear-implants-market (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Cejas, I.; Barker, D.H.; Petruzzello, E.; Sarangoulis, C.M.; Quittner, A.L. Costs of Severe to Profound Hearing Loss & Cost Savings of Cochlear Implants. Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 4358–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neve, O.M.; Boerman, J.A.; Van Den Hout, W.B.; Briaire, J.J.; Van Benthem, P.P.G.; Frijns, J.H.M. Cost-benefit Analysis of Cochlear Implants: A Societal Perspective. Ear Hear. 2021, 42, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRajhi, B.; AlGhamdi, M.A.; Alenazi, N.; Alabssi, H.; Alshammeri, S.T.; Aloweiny, Q.; Bogari, H.; Al-Subaie, H. Incidence of Cochlear Implantation Complications in Saudi Arabia: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of the Literature. Cureus 2024, 16, e60488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, K.S.; Mughal, Y.H.; Albejaidi, F.; Alharbi, A.H. Healthcare Financing in Saudi Arabia: A Comprehensive Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athalye, S.; Archbold, S.; Mulla, I.; Lutman, M.; Nikolopoulous, T. Exploring views on current and future cochlear implant service delivery: The perspectives of users, parents and professionals at cochlear implant centres and in the community. Cochlear Implant. Int. 2015, 16, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Current Age (n = 86) | Median: 38 years | IQR: 27 to 46 years |

| Age at CI (n = 86) | Median: 30 years | IQR: 25 to 40 years |

| Duration of CI experience (n = 86) | Median: 3 years | IQR: 1 to 6 years |

| Hearing Solution (n = 86) | CI Unilateral | 57% |

| Bimodal | 17% | |

| CI Bilateral | 26% | |

| Onset of hearing loss (n = 98) (Categorised from self-stated free text) | Childhood | 29% |

| Adult, fast onset | 27% | |

| Adult, gradual onset | 17% | |

| Unknown | 37% | |

| Education Level (n = 86) | Less than high school | 21% |

| High school/GED | 21% | |

| College (2-year) | 17% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 35% | |

| Master’s degree | 5% | |

| Ph.D. | 1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bin Dehaish, S.; Bin Marouq, A.; Almalki, A.; Yousef, M.; Almuhawas, F.; Hagr, A.; Mony, J.; Albaqeyah, M.; Alferaih, H.; Alqahtani, H.; et al. Cochlear Implants and Adult Patient Experiences, Adaptation and Challenges: A Survey. Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060166

Bin Dehaish S, Bin Marouq A, Almalki A, Yousef M, Almuhawas F, Hagr A, Mony J, Albaqeyah M, Alferaih H, Alqahtani H, et al. Cochlear Implants and Adult Patient Experiences, Adaptation and Challenges: A Survey. Audiology Research. 2025; 15(6):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060166

Chicago/Turabian StyleBin Dehaish, Sahar, Abdulmalik Bin Marouq, Abdulaziz Almalki, Medhat Yousef, Fida Almuhawas, Abdulrahman Hagr, Jad Mony, Mohammad Albaqeyah, Hala Alferaih, Haifa Alqahtani, and et al. 2025. "Cochlear Implants and Adult Patient Experiences, Adaptation and Challenges: A Survey" Audiology Research 15, no. 6: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060166

APA StyleBin Dehaish, S., Bin Marouq, A., Almalki, A., Yousef, M., Almuhawas, F., Hagr, A., Mony, J., Albaqeyah, M., Alferaih, H., Alqahtani, H., Alghuraibi, S., Poovayya, D., Yalcouy, H., & Alrushaydan, D. (2025). Cochlear Implants and Adult Patient Experiences, Adaptation and Challenges: A Survey. Audiology Research, 15(6), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060166