Identifying Hearing Loss and Audiological Rehabilitation Candidacy Through Self-Perceived Hearing Handicap Using the Croatian Version of the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly—Screening (HHIE-S-CRO)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

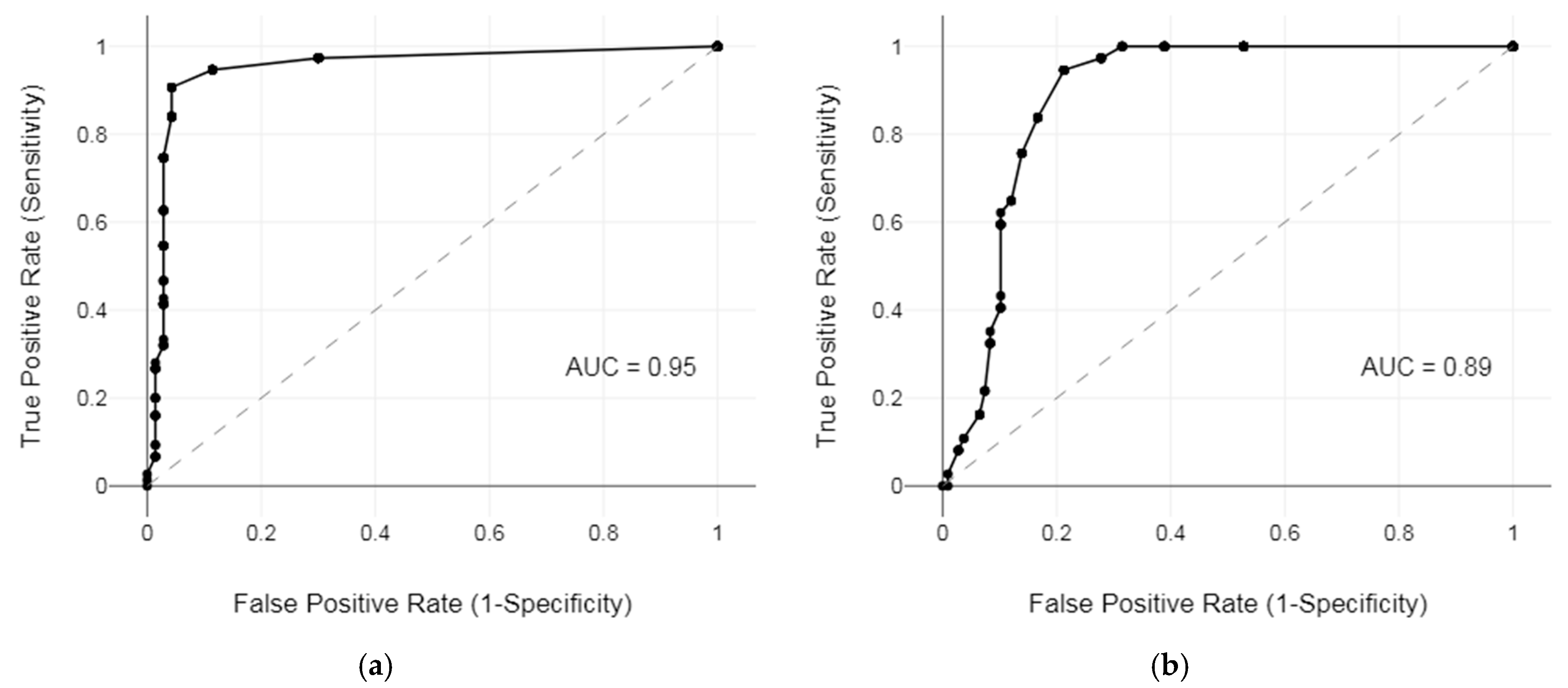

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HHIE-S-CRO | Croatian adaptation of HHIE-S |

| dB HL | Decibels hearing level |

| ROC curve | Receiver operating characteristic curve |

| PPV | positive predictive values |

| NPV | negative predictive values |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| HHIE-S | The Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly—Screening Version |

| PTA | Pure tone average |

| BE PTA-4 | Four frequency better ear PTA |

References

- World Health Organization. Deafness and Hearing Loss. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Quick Statistics About Hearing. Available online: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Duchêne, J.; Billiet, L.; Franco, V.; Bonnard, D. Validation of the French Version of HHIE-S (Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly—Screening) Questionnaire in French Over-60 Year-Olds. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2022, 139, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheslock, M.; De Jesus, O. Presbycusis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R.J.; Saulsman, L.; Eikelboom, R.H.; Olaithe, M. Coping with the Social Challenges and Emotional Distress Associated with Hearing Loss: A Qualitative Investigation Using Leventhal’s Self-Regulation Theory. Int. J. Audiol. 2022, 61, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contrera, K.J.; Betz, J.; Deal, J.A.; Choi, J.S.; Ayonayon, H.N.; Harris, T.; Helzner, E.; Martin, K.R.; Mehta, K.; Pratt, S.; et al. Association of Hearing Impairment and Emotional Vitality in Older Adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, S.E.; Kapteyn, T.S.; Kuik, D.J.; Deeg, D.J. The Association of Hearing Impairment and Chronic Diseases with Psychosocial Health Status in Older Age. J. Aging Health 2002, 14, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, J.; Popli, G.; Fell, G. Association of Cognition and Age-Related Hearing Impairment in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 144, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzani, D.; Galeazzi, G.M.; Genovese, E.; Marrara, A.; Martini, A. Psychological Profile and Social Behaviour of Working Adults with Mild or Moderate Hearing Loss. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2008, 28, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, G.; Sommerlad, A.; Orgeta, V.; Costafreda, S.G.; Huntley, J.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; et al. Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care. Lancet 2017, 390, 2673–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gispen, F.E.; Chen, D.S.; Genther, D.J.; Lin, F.R. Association between Hearing Impairment and Lower Levels of Physical Activity in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 1427–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiely, K.M.; Gopinath, B.; Mitchell, P.; Luszcz, M.; Anstey, K.J. Cognitive, Health, and Sociodemographic Predictors of Longitudinal Decline in Hearing Acuity among Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2012, 67, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mener, D.J.; Betz, J.; Genther, D.J.; Chen, D.; Lin, F.R. Hearing Loss and Depression in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 1627–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsimpida, D.; Kontopantelis, E.; Ashcroft, D.; Panagioti, M. Comparison of Self-Reported Measures of Hearing with an Objective Audiometric Measure in Adults in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2015009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, A.D.; Dickson, G.M. Hearing Loss in Older Adults. Am. Fam. Physician 2012, 85, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F.R.; Metter, E.J.; O’Brien, R.J.; Resnick, S.M.; Zonderman, A.B.; Ferrucci, L. Hearing Loss and Incident Dementia. Arch. Neurol. 2011, 68, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löhler, J.; Cebulla, M.; Shehata-Dieler, W.; Volkenstein, S.; Völter, C.; Walther, L.E. Hearing Impairment in Old Age. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2019, 116, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R.; Dana, T.; Bougatsos, C.; Fleming, C.; Beil, T. Screening Adults Aged 50 Years or Older for Hearing Loss: A Review of the Evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 154, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, B.E.; Ventry, I.M. Hearing Impairment and Social Isolation in the Elderly. J. Speech Hear. Res. 1982, 25, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenstein, M.J.; Bess, F.H.; Logan, S.A. Validation of Screening Tools for Identifying Hearing-Impaired Elderly in Primary Care. JAMA 1988, 259, 2875–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Y.J.; Wang, S.Y.; Wu, C.J.; Tsai, C.Y.; Wu, T.F.; Lin, Y.S. Screening for Hearing Impairment in Older Adults by Smartphone-Based Audiometry, Self-Perception, HHIE Screening Questionnaire, and Free-Field Voice Test. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e17213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, M.J.; Hazuda, H.P. Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly-Screening Version (HHIE-S) for Use with Spanish-Speaking Mexican Americans. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1998, 46, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jupiter, T.; Palagonia, C.L. The Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly Screening Version Adapted for Use with Elderly Chinese American Individuals. Am. J. Audiol. 2001, 10, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salonen, J.; Johansson, R.; Karjalainen, S.; Vahlberg, T.; Isoaho, R. Relationship between Self-Reported Hearing and Measured Hearing Impairment in an Elderly Population in Finland. Int. J. Audiol. 2011, 50, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, B.E.; Rasheedy, D.; Taha, H.M.; Fatouh, F.N. Cross-Cultural Adaptation of an Arabic Version of the 10-Item Hearing Handicap Inventory. Int. J. Audiol. 2015, 54, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öberg, M. Validation of the Swedish Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (Screening Version) and Evaluation of Its Effect in Hearing Aid Rehabilitation. Trends Hear. 2016, 20, 2331216516639234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mo, L.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Qi, Y. Analysing Use of the Chinese HHIE-S for Hearing Screening of Elderly in a Northeastern Industrial Area of China. Int. J. Audiol. 2016, 56, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apa, E.; Sacchetto, L.; Palma, S.; Cocchi, C.; Gherpelli, C.; Genovese, E.; Monzani, D.; Nocini, R. Italian Validation of the Hearing Handicap Inventory for Elderly—Screening Version (HHIE-S-It). Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2023, 43, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, L.; Šimunjak, B.; Franić, J. Validation of Self-Reported Hearing Loss among Adult Croatians. Int. J. Audiol. 2018, 57, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 USA Hearing Loss Collaborators; Haile, L.M.; Orji, A.U.; Reavis, K.M.; Briant, P.S.; Lucas, K.M.; Alahdab, F.; Bärnighausen, T.W.; Bell, A.; Cao, C.; et al. Hearing Loss Prevalence, Years Lived with Disability, and Hearing Aid Use in the United States From 1990 to 2019. Ear Hear. 2024, 45, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, A.; Houmøller, S.S.; Tsai, L.T.; Hougaard, D.D.; Gaihede, M.; Hammershøi, D.; Schmidt, J.H. The Effect of Hearing Aid Treatment on Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults with Hearing Loss. Int. J. Audiol. 2024, 63, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, A.; Smith, B.; Ray, J. The Impact of Rehabilitation on Quality of Life after Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 275, 2435–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Hearing; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-002048-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pravilnik o Ortopedskim i Drugim Pomagalima. Narodne Novine: 62/19, 2019, Zagreb, Croatia. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- ISO 8253-1:2010; Acoustics—Audiometric Test Methods—Part 1: Pure-Tone Air and Bone Conduction Audiometry. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 1–30.

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. 11.0 Update, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; p. 371. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandrekar, J.N. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve in Diagnostic Test Assessment. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010, 5, 1315–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.H.; Chu, Y.C.; Chen, Y.F.; Chen, M.Y.; Cheng, Y.F.; Wu, C.S.; Huang, H.M. Diagnostic Validity of Self-Reported Hearing Loss in Elderly Taiwanese Individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.P.; Ho, C.Y.; Chou, P. Factors Associated with a Self-Perceived Hearing Handicap in Elderly People with Hearing Impairment. Ear Hear. 2009, 30, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, L.K.; Matthews, L.J.; Dubno, J.R. Prevalence of Self-Reported Hearing Difficulty on the Revised Hearing Handicap Inventory. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasekaran, V.; Gurulakshmi, R.B. Assessment of the Self-Perceived Hearing Handicap and Its Associated Factors in Elderly People with Hearing Loss. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2018, 12, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuesse, T.; Schlueter, A.; Lemke, U.; Holube, I. Self-Reported Hearing Handicap in Adults Aged 55 to 81 Years. Int. J. Audiol. 2021, 60 (Suppl. S2), 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, G.A.; Murphy, M.; Rees, T.S.; Fraher, A. Screening for handicapping hearing loss in the elderly. J. Fam. Pract. 2003, 52, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A.K.; Ahsan, A.; Kumar, V. mpact of Hearing Aid Usage on Emotional and Social Skills in Persons with Severe to Profound Hearing Loss. J. Audiol. Otol. 2023, 27, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podury, A.; Jiam, N.T.; Kim, M.; Donnenfield, J.I.; Dhand, A. Hearing and sociality: The implications of hearing loss on social life. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1245434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieur Chaintré, A.; Couturier, Y.; Nguyen, T.H.T.; Levasseur, M. Influence of Hearing Loss on Social Participation in Older Adults: Results from a Scoping Review. Res. Aging 2024, 46, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldè, M.; Ambrosetti, U.; Barozzi, S.; Aldè, S. The Ongoing Challenges of Hearing Loss: Stigma, Socio-Cultural Differences, and Accessibility Barriers. Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Državni Zavod za Statistiku. Women and Men in Croatia 2021; Državni Zavod za Statistiku: Zagreb, Croatia, 2021; Available online: https://podaci.dzs.hr/media/zoyp1kuq/men_and_women_2021.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

| Age Group | Means and Standard Deviations of Audiometric Measures | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing Participants (BE PTA-4 * ≤ 20 dB HL; N = 70) | Participants with Hearing Loss (BE PTA-4 * > 20 dB HL; N = 75) | Participants with Hearing Loss Eligible for State-Funded Hearing Aid Rehabilitation (BE PTA-4 * ≥ 40 dB HL; N = 37) | |

| 60–69 years | M = 14.89 dB HL (±3.21) Range: 8–20 dB HL N = 38 (26 females and 12 males) | M = 42.21 dB HL (±9.42) Range: 23–69 dB HL N = 19 (10 females and 9 males) | M = 47.45 dB HL (±7.92) Range: 41–69 dB HL N = 11 (5 females and 6 males) |

| 70–79 years | M = 14.92 dB HL (±3.05) Range: 9–20 dB HL N = 24 (18 females and 6 males) | M = 38.83 dB HL (±9.90) Range: 25–63 dB HL N = 42 (28 females and 14 males) | M = 49.13 dB HL (±6.70) Range: 41–63 dB HL N = 16 (11 females and 5 males) |

| 80–89 years | M = 16.36 dB HL (±2.12) Range: 9–20 dB HL N = 8 (5 females and 3 males) | M = 47.64 dB HL (±10.98) Range: 23–65 dB HL N = 14 (8 females and 6 males) | M = 53.10 dB HL (±6.80) Range: 45–65 dB HL N = 10 (5 females and 5 males) |

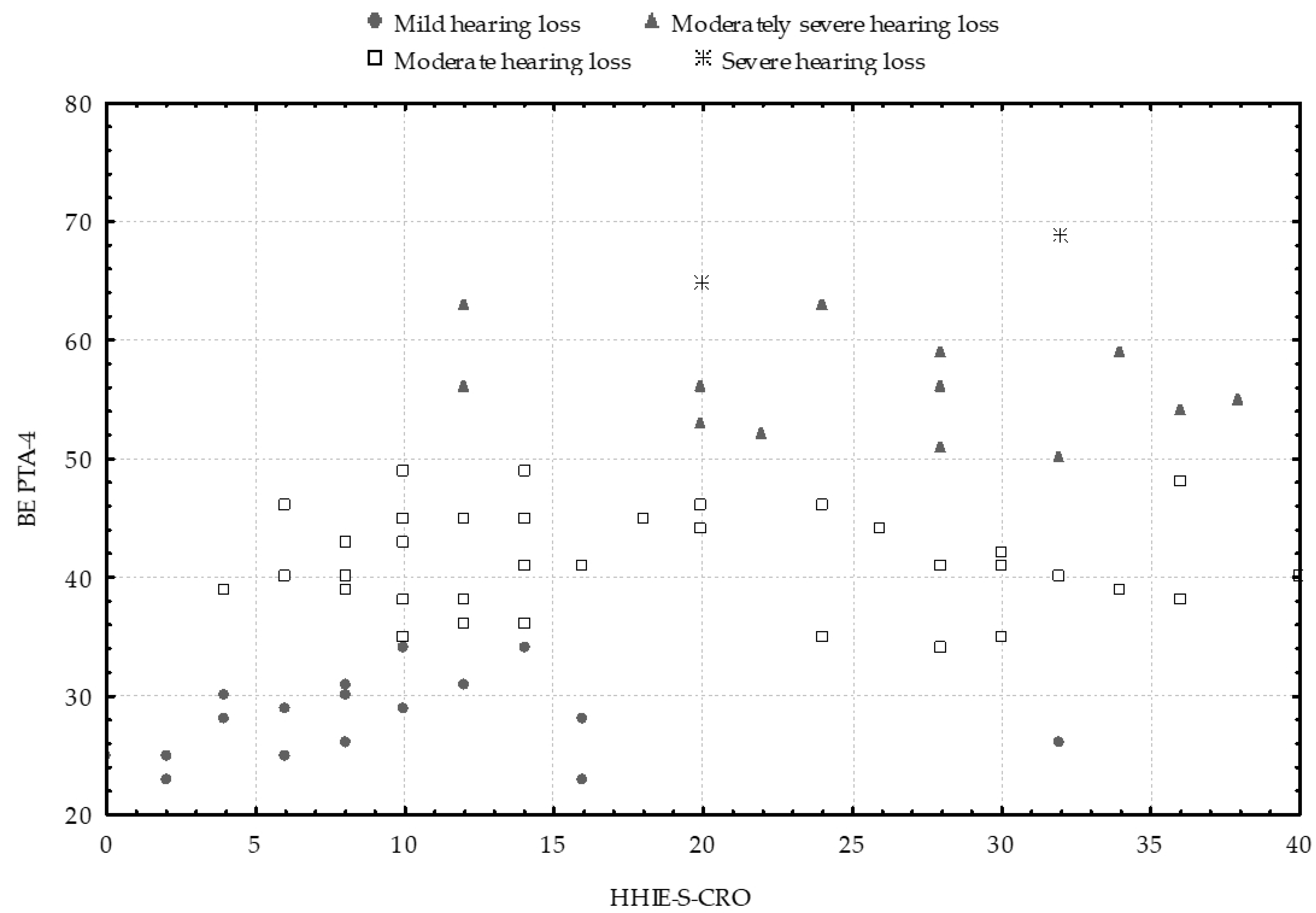

| Mild hearing loss (BE PTA-4 20 to <35 dB HL) | All participants within this hearing loss grade were not eligible for hearing aid rehabilitation supported by state funds under Croatian national criteria BE PTA-4 * ≥ 40 dB HL:

|

| Moderate hearing loss (BE PTA-4 35 to <50 dB HL) | All participants within this hearing loss grade:

|

| Moderately severe hearing loss (BE PTA-4 50 to <65 dB HL) | All participants within this hearing loss grade were eligible for hearing aid rehabilitation supported by state funds under Croatian national criteria BE PTA-4 * ≥ 40 dB HL:

|

| Severe hearing loss (BE PTA-4 65 to <80 dB HL) | All participants within this hearing loss grade were eligible for hearing aid rehabilitation supported by state funds under Croatian national criteria BE PTA-4 * ≥ 40 dB HL:

|

| BE PTA-4 * > 20 dB HL Criteria | BE PTA-4 * ≥ 40 dB HL Criteria | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HHIE-S-CRO Item (English/Croatian) E—Emotional Item S—Social Item | Answer | Hearing Group (N = 70) | Hearing Loss Group (N = 75) | Not Eligible for State-Funded Hearing Aid Rehabilitation (N = 108) | Eligible for State-Funded Hearing Aid Rehabilitation (N = 37) |

| 1. (E) Does a hearing problem cause you to feel embarrassed when meeting new people? (Osjećate li se neugodno zbog slušnih problema kada upoznajete nove ljude?) | No | 98.57% | 38.67% | 85.05% | 18.42% |

| Sometimes | - | 24.00% | 5.61% | 31.58% | |

| Yes | 1.43% | 37.33% | 9.35% | 50.00% | |

| 2. (E) Does a hearing problem cause you to feel frustrated when talking to members of your family? (Čine li Vas slušni problemi frustriranima kada razgovarate s članovima obitelji?) | No | 95.71% | 40.00% | 79.44% | 31.58% |

| Sometimes | 1.43% | 30.67% | 10.28% | 34.21% | |

| Yes | 2.86% | 29.33% | 10.28% | 34.21% | |

| 3. (S) Do you have difficulty hearing when someone speaks in a whisper? (Imate li poteškoća sa slušanjem kada netko šapće?) | No | 72.86% | 10.67% | 52.34% | 7.89% |

| Sometimes | 22.86% | 8.00% | 16.82% | 10.53% | |

| Yes | 4.28% | 81.33% | 30.84% | 81.58% | |

| 4. (E) Do you feel handicapped by a hearing problem? (Osjećate li se zbog slušnih problema hendikepiranima?) | No | 97.14% | 64.00% | 88.78% | 55.26% |

| Sometimes | - | 20.22% | 4.68% | 26.32% | |

| Yes | 2.86% | 16.00% | 6.54% | 18.42% | |

| 5. (S) Does a hearing problem cause you difficulty when visiting friends, relatives, or neighbors? (Uzrokuju li Vam slušni problemi teškoće kada posjećujete prijatelje, rodbinu ili susjede?) | No | 97.14% | 58.67% | 89.72% | 42.11% |

| Sometimes | - | 9.33% | 1.87% | 13.15% | |

| Yes | 2.86% | 32.00% | 8.41% | 44.74% | |

| 6. (S) Does a hearing problem cause you to attend religious services less often than you would like? (Prisustvujete li zbog slušnih problema bogoslužju rjeđe nego što biste voljeli?) | No | 100% | 78.67% | 94.39% | 73.68% |

| Sometimes | - | 2.66% | - | 5.26% | |

| Yes | - | 18.67% | 5.61% | 21.06% | |

| 7. (E) Does a hearing problem cause you to have arguments with family members? (Uzrokuju li Vam slušni problemi prepirke s članovima obitelji?) | No | 97.14% | 57.33% | 84.11% | 55.26% |

| Sometimes | - | 17.33% | 5.61% | 18.42% | |

| Yes | 2.86% | 25.34% | 10.28% | 26.32% | |

| 8. (S) Does a hearing problem cause you difficulty when listening to TV or radio? (Uzrokuju li Vam slušni problemi teškoće pri slušanju televizije ili radija?) | No | 90.00% | 29.33% | 75.70% | 10.52% |

| Sometimes | 8.57% | 22.67% | 11.21% | 28.95% | |

| Yes | 1.43% | 48.00% | 13.09% | 60.53% | |

| 9. (E) Do you feel that any difficulty with your hearing limits or hampers your personal or social life? (Smatrate li da neka poteškoća s Vašim slušanjem ograničava ili sputava Vaš osobni ili društveni život?) | No | 94.28% | 57.33% | 85.98% | 44.74% |

| Sometimes | 2.86% | 17.33% | 5.61% | 23.68% | |

| Yes | 2.86% | 25.34% | 8.41% | 31.58% | |

| 10. (S) Does a hearing problem cause you difficulty when in a restaurant with relatives or friends? (Uzrokuju li Vam slušni problemi teškoće kada ste u restoranu s rodbinom ili prijateljima?) | No | 97.14% | 45.33% | 83.18% | 34.21% |

| Sometimes | - | 22.67% | 4.67% | 31.58% | |

| Yes | 2.86% | 32.00% | 12.15% | 34.21% | |

| Audiometric Criteria | HHIE-S-CRO Subscale | Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | Z | p | |||

| BE PTA-4 > 20 dB HL (N = 75) | Emotional | Mean = 7.39 (±5.95) Range: 0–20 | 392.50 | 4.214 | <0.001 |

| Social | Mean = 9.76 (±5.55) Range: 0–20 | ||||

| BE PTA-4 ≥ 40 dB HL (N = 37) | Emotional | Mean = 9.30 (±4.97) Range: 0–18 | 120.50 | 2.859 | 0.004 |

| Social | Mean = 11.57 (±5.15) Range: 2–20 | ||||

| Audiometric Criteria | HHIE-S-CRO | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

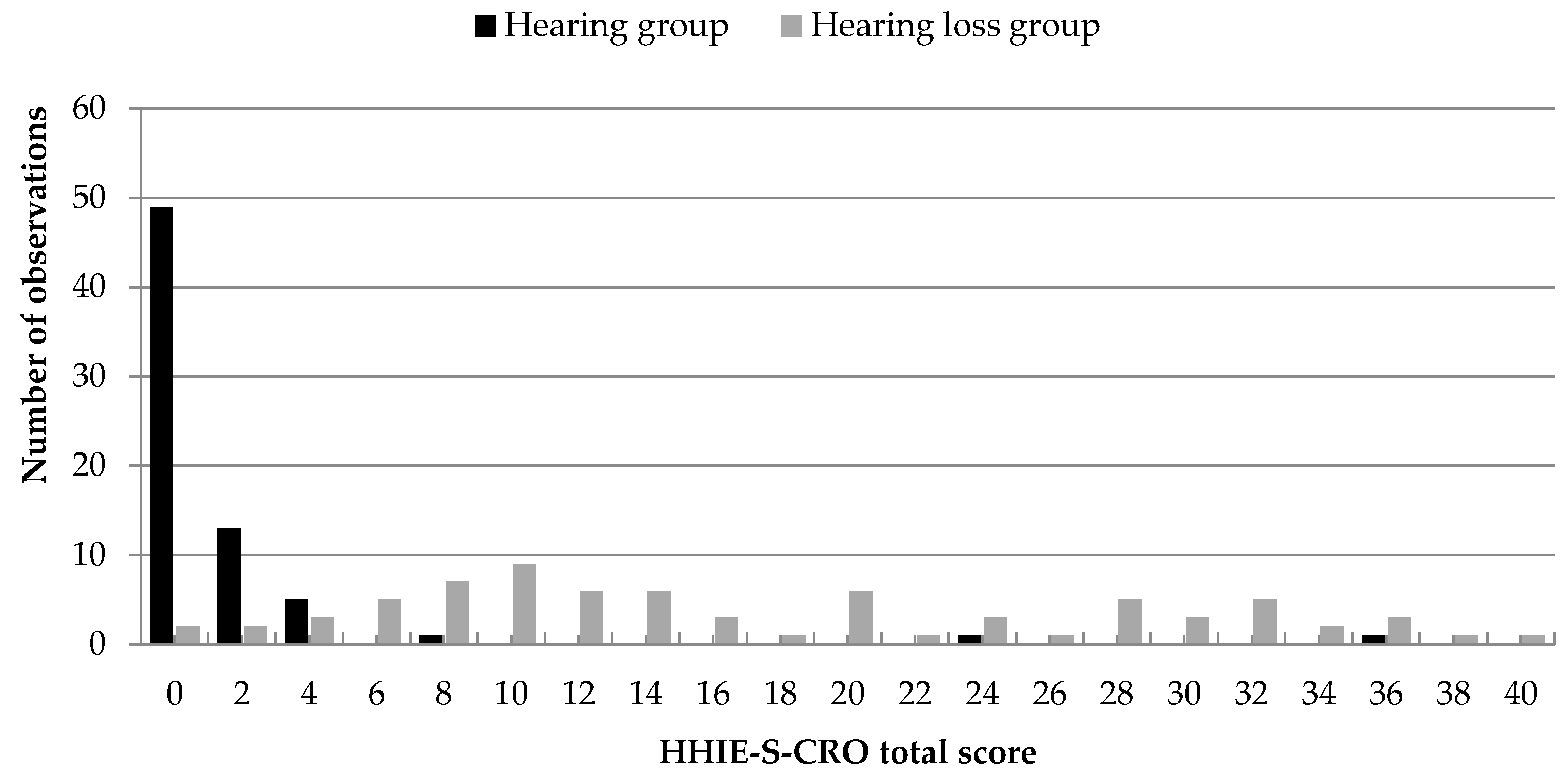

| Rank Sum | U | p | ||

| BE PTA-4 > 20 dB HL | Hearing group (N = 70) | 2740.00 | 255 | <0.001 |

| Hearing loss group (N = 75) | 7845.00 | |||

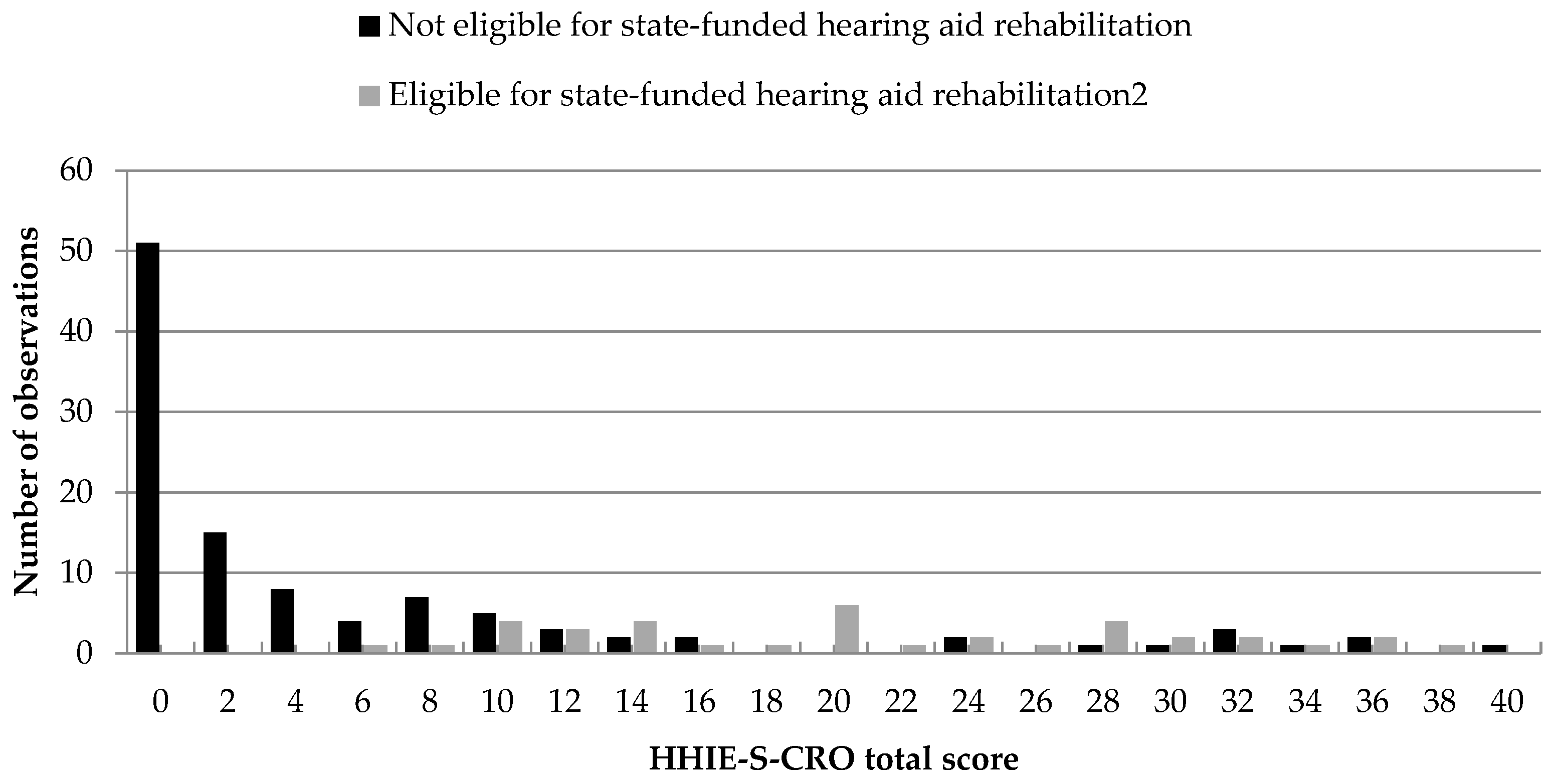

| BE PTA-4 ≥ 40 dB HL | Eligible for state-funded hearing aid rehabilitation (N = 108) | 4255.50 | 443.50 | <0.001 |

| Not eligible for state-funded hearing aid rehabilitation (N = 37) | 6329.50 | |||

| Factor | |

|---|---|

| 1. (E) Does a hearing problem cause you to feel embarrassed when meeting new people? | 0.81 |

| 2. (E) Does a hearing problem cause you to feel frustrated when talking to members of your family? | 0.71 |

| 3. (S) Do you have difficulty hearing when someone speaks in a whisper? | 0.64 |

| 4. (E) Do you feel handicapped by a hearing problem? | 0.74 |

| 5. (S) Does a hearing problem cause you difficulty when visiting friends, relatives, or neighbors? | 0.83 |

| 6. (S) Does a hearing problem cause you to attend religious services less often than you would like? | 0.55 |

| 7. (E) Does a hearing problem cause you to have arguments with family members? | 0.70 |

| 8. (S) Does a hearing problem cause you difficulty when listening to TV or radio? | 0.71 |

| 9. (E) Do you feel that any difficulty with your hearing limits or hampers your personal or social life? | 0.77 |

| 10. (S) Does a hearing problem cause you difficulty when in a restaurant with relatives or friends? | 0.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bonetti, L.; Bonetti, A.; Krišto, T. Identifying Hearing Loss and Audiological Rehabilitation Candidacy Through Self-Perceived Hearing Handicap Using the Croatian Version of the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly—Screening (HHIE-S-CRO). Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15050116

Bonetti L, Bonetti A, Krišto T. Identifying Hearing Loss and Audiological Rehabilitation Candidacy Through Self-Perceived Hearing Handicap Using the Croatian Version of the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly—Screening (HHIE-S-CRO). Audiology Research. 2025; 15(5):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15050116

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonetti, Luka, Ana Bonetti, and Tea Krišto. 2025. "Identifying Hearing Loss and Audiological Rehabilitation Candidacy Through Self-Perceived Hearing Handicap Using the Croatian Version of the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly—Screening (HHIE-S-CRO)" Audiology Research 15, no. 5: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15050116

APA StyleBonetti, L., Bonetti, A., & Krišto, T. (2025). Identifying Hearing Loss and Audiological Rehabilitation Candidacy Through Self-Perceived Hearing Handicap Using the Croatian Version of the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly—Screening (HHIE-S-CRO). Audiology Research, 15(5), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15050116