Adaptation of the Kiswahili and Lingala Versions of the LittlEARS® Auditory Questionnaire (LEAQ) in Children with Normal Hearing in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

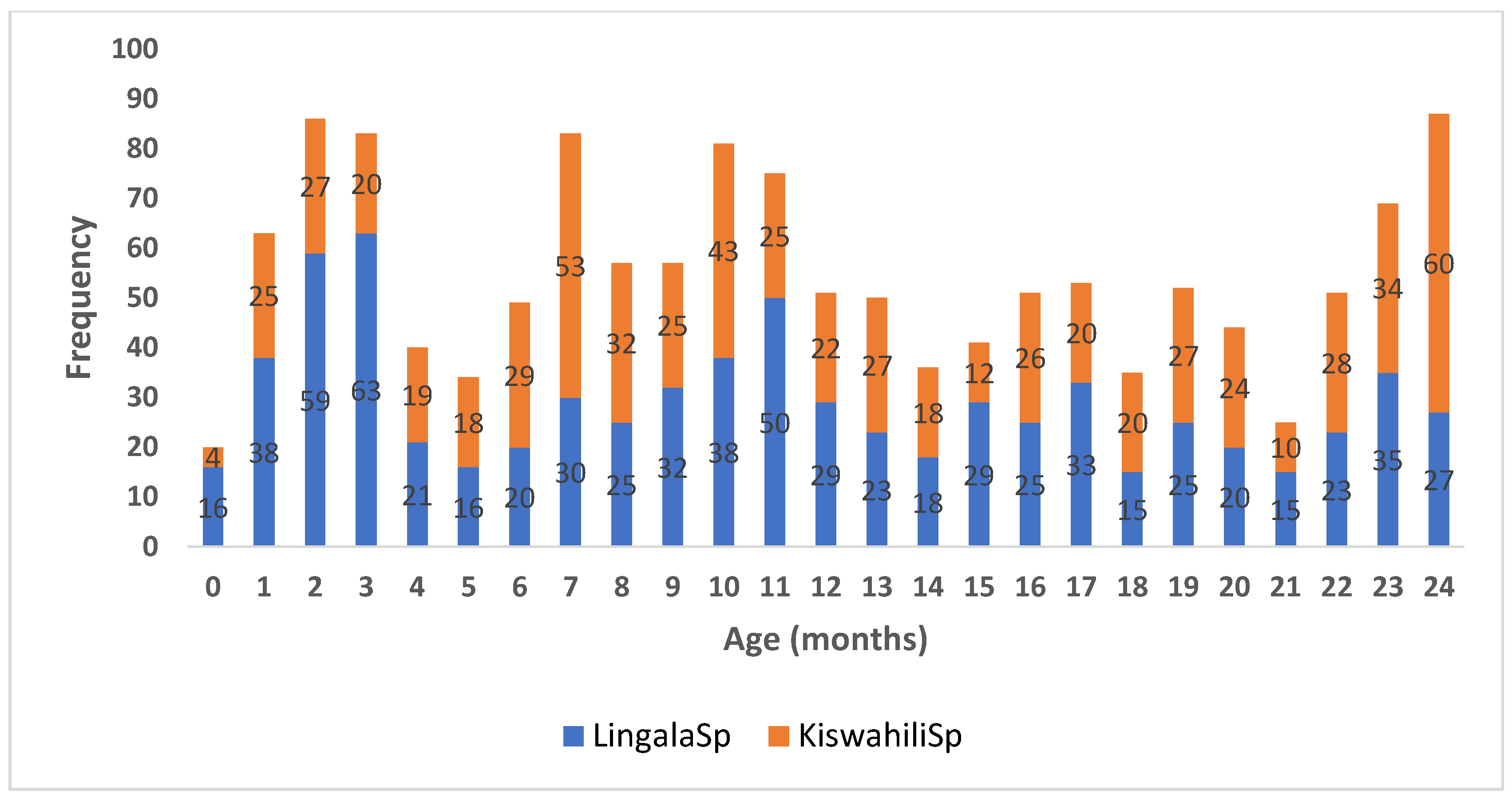

2.1. Participants and Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

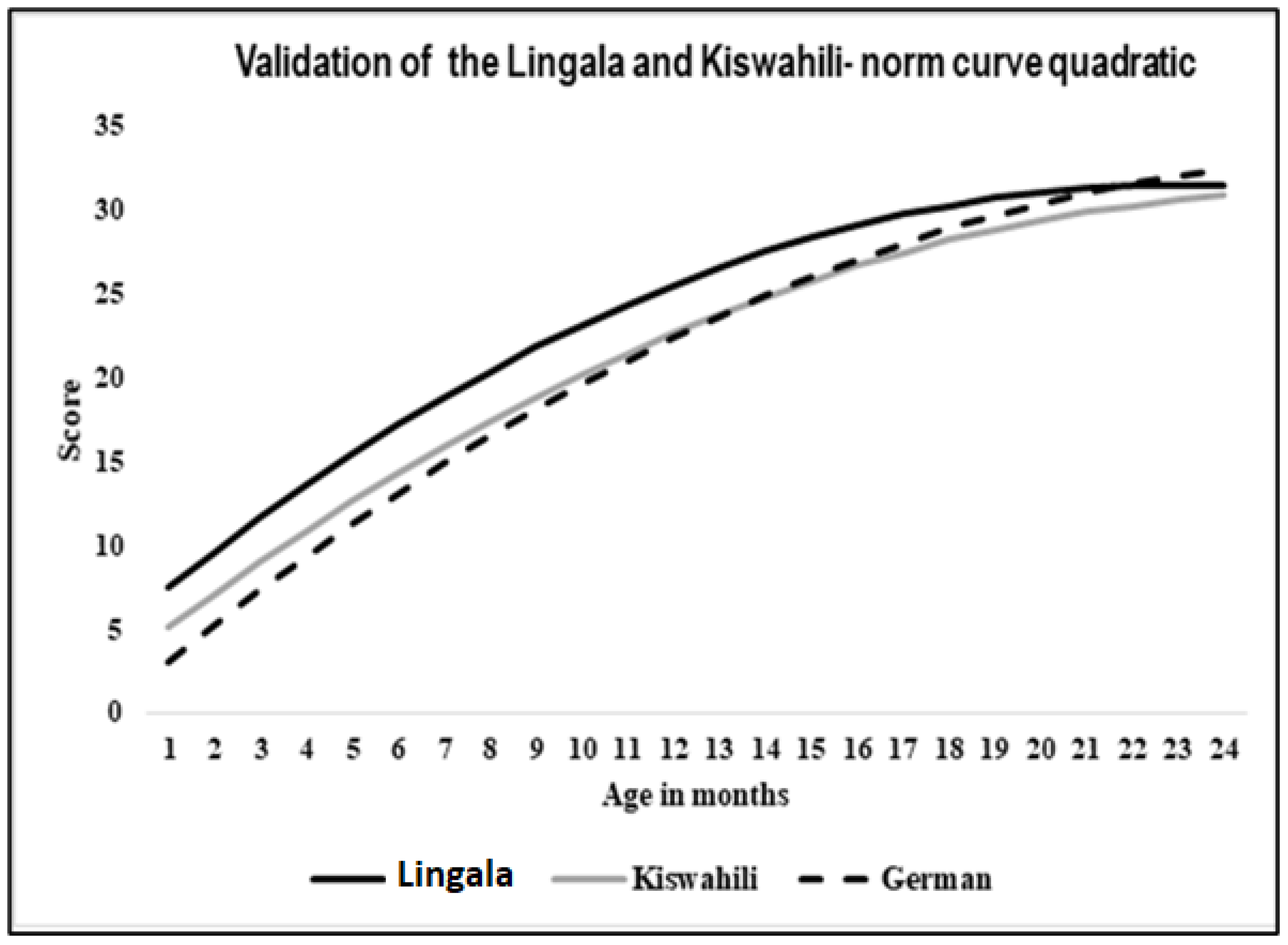

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coninx, F.; Weichbold, V.; Tsiakpini, L.; Autrique, E.; Bescond, G.; Tamas, L.; Compernol, A.; Georgescu, M.; Koroleva, I.; Le Maner-Idrissi, G.; et al. Validation of the LittlEARS® Auditory Questionnaire in children with normal hearing. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2009, 73, 1761–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May-Mederake, B.; Kuehn, H.; Vogel, A.; Keilmann, A.; Bohnert, A.; Mueller, S.; Coninx, F. Evaluation of auditory development in infants and toddlers who received cochlear implants under the age of 24 months with the LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire. Int. J. Paediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2010, 74, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weichbold, V.; Tsiakpini, L.; Coninx, F.; D’Haese, P. Development of a parent questionnaire for assessment of auditory behaviour of infants up to two years of age. Laryngorhinootologie 2005, 84, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman-Phillips, S.; Robbins, A.M.; Osberger, M.J. Infant-Toddler Meaningful Integration Scale; Advanced Bionics Corporation: Sylmar, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Purdy, S.C.; Farrington, D.R.; Moran, C.A.; Chard, L.L.; Hodgson, S.A. A Parental Questionnaire to Evaluate Children’s Auditory Behavior in Everyday Life (ABEL). Am. J. Audiol. 2002, 11, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenson, L.; Pethick, S.; Renda, C.; Cox, J.L.; Reznick, S.J. Short-form versions of the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories: In infant behaviour and development. Appl. Psycholinguist. 2000, 21, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagatto, M.P.; Brown, C.L.; Moodie, S.T.; Scollie, S.D. External validation of the LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire with English-speaking families of Canadian children with normal hearing. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2011, 75, 815–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Orom, H.; Hay, J.L.; Waters, E.A.; Schofield, E.; Li, Y.; Kiviniemi, M.T. Differences in Rural and Urban Health Information Access and Use. J. Rural Health Off. J. Am. Rural Health Assoc. Natl. Rural Health Care Assoc. 2019, 35, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaremi, O.D.; Olatokun, W. Survey of health information source use in rural communities identifies complex health literacy barriers. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2022, 39, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, Z.T.; Worku, M.G.; Tesema, G.A.; Alamneh, T.S.; Teshale, A.B.; Yeshaw, Y.; Alem, A.Z.; Ayalew, H.G.; Liyew, A.M. Determinants of accessing healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa: A mixed-effect analysis of recent Demographic and Health Surveys from 36 countries. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e054397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministère du Plan et Suivi de la Mise en œuvre de la Révolution de la Modernité (MPSMRM); Ministère de la Santé Publique (MSP); ICF International. EDS-RDC II. Democratic Republic of Congo Demographic and Health Survey 2013-14. 2014. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/sr218/sr218.e.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- RDC-Institut National de la Statistique, École de Santé Publique de Kinshasa et ICF. EDS–RDC III. RDC, Enquête Démographique et de Santé 2023–24: Rapport des indicateurs clés. Kinshasa. 2024. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR156/PR156.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Ministry of Health (MoH)—DRCongo. Rapport de la Restitution des Résultats de la Cartographie des Besoins des Sites des Soins Communautaires. PNLMD. Du 23 au 24 Mars. 2015. Available online: https://www.prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/RDC-Plan-National-de-Developpement-Sanitaire-2016-2020.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Schaefer, K.; Coninx, F.; Fischbach, T. LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire as an infant hearing screening in Germany after the newborn hearing screening. Int. J. Audiol. 2019, 58, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offei, Y.N.; Coninx, F. Mode of administration of LittlEARS® (MED-EL) Auditory Questionnaire (LEAQ) as a screening tool in Ghana: Are there any differences in final test scores between “self-administration” and “interview”? J. Educ. Pract. 2014, 5, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rauhamäki, T.; Lonka, E.; Lipsanen, J.; Laakso, M. Assessment of early auditory development of very young Finnish children with LittlEARS® Auditory Questionnaire and McArthur Communicative Developmental Inventories. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014, 78, 2089–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzeldina, H.; Kaddah, E.Z.; Hameed, A.A. The use of the LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire in assessing children before and after cochlear implantation. Egypt. J. Otolaryngol. 2018, 34, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.A.; Zaragoza Domingo, S.; Hamdache, L.Z.; Manchaiah, V.; Thammaiah, S.; Evans, C.; Wong, L.L.N.; International Collegium of Rehabilitative Audiology and TINnitus Research NETwork. A good practice guide for translating and adapting hearing-related questionnaires for different languages and cultures. Int. J. Audiol. 2018, 57, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Translators without Borders—US, Inc. The Four National Languages of DRC. 2021. Available online: https://translatorswithoutborders.org/four-national-languages-drc (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Nuzzo, R.L. Histograms: A Useful Data Analysis Visualization. Am. Acad. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 11, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrycka, A.; Pankowska, A.; Lorens, A.; Skarzynski, H. Production and evaluation of a Polish version of the LittlEars questionnaire for the assessment of auditory development in infants. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2009, 73, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, X.; Liang, W.; Chen, J.; Zheng, W. Validation of the Mandarin Version of the LittlEARS® Auditory Questionnaire. Int. J. Paediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 77, 1350–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geal-Dor, M.; Jbarah, R.; Meilijson, S.; Adelman, A.; Levi, H. The Hebrew and the Arabic version of the LittlEARS(R) Auditory Questionnaire for the assessment of auditory development: Results in normal hearing children and children with cochlear implants. Int. J. Paediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2011, 75, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, G.A.S.; García, P.J.L.; Quevedo, S.M. Production and evaluation of a Spanish version of the LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire for the assessment of auditory development in children. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 83, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, J.B.; Zavala, J.S. Development of Spanish version of the LittlEARS parental questionnaire for use in the United States and Latin America. Audiol. Res. 2011, 1, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayode, O.; Adeyemo, A.A. The Yoruba version of LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire: Evaluation of auditory development in children with normal hearing. J. Otol. 2018, 13, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, A.; Miniscalco, C.; Lohmander, A.; Flynn, T. Validation of the Swedish version of the LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire in children with normal hearing—A longitudinal study. Int. J. Audiol. 2019, 58, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miggiani, P.; Coninx, F.; Schaefer, K. Validation of the LittlEARS® Questionnaire in Hearing Maltese-Speaking Children. Audiol. Res. 2022, 12, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarifiana, T.; Movallalib, G.; Fotuhia, M.; Harouni, G.G. Validation of the Persian version of the LittlEARS® Auditory Questionnaire for assessment of auditory development in children with normal hearing. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 123, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Lingala Version (n = 723) | Kiswahili Version (n = 648) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Score M (Range) | SD | Pearson Correlation Coefficient | Score M (Range) | SD | Pearson Correlation Coefficient |

| Age | 10.92 (0–35) | 7.2 | 0.77 ** | 12.72 (0–35) | 7.25 | 0.81 ** |

| Scores | 21.81 | 10.53 | 22.2 | 10.46 | ||

| Country (Language) | Sample Size (n) | Corr. Age + Total Score * |

|---|---|---|

| Belgium (Flemish) | 142 | 0.93 |

| Bulgaria (Bulgarian) | 101 | 0.82 |

| China (Mandarin) | 157 | 0.84 |

| Finland (Finnish) | 364 | 0.91 |

| France (French) | 216 | 0.83 |

| Germany/Austria (German) | 218 | 0.91 |

| Greece (Greek) | 93 | 0.80 |

| Poland (Polish) | 325 | 0.90 |

| Romania (Romanian) | 88 | 0.80 |

| Russia (Russian) | 180 | 0.93 |

| Serbia (Serbian) | 183 | 0.86 |

| Slovakia (Slovak) | 592 | 0.92 |

| Slovenia (Slovenian) | 366 | 0.92 |

| Switzerland (German) | 92 | 0.92 |

| Malta (Maltese) | 398 | 0.90 |

| USA (English) | 144 | 0.85 |

| USA (Spanish) | 48 | 0.93 |

| Overall | 3309 | 0.89 |

| DRC/Africa (Lingala) | 723 | 0.77 |

| DRC/Africa (Kiswahili) | 648 | 0.81 |

| Dependent Variables | N | Mean |

|---|---|---|

| 62 | 22.45 |

| 179 | 21.92 |

| 456 | 21.65 |

| 25 | 22.48 |

| Dependent Variables | N | Mean |

|---|---|---|

| 455 | 22.27 |

| 108 | 23.15 |

| 85 | 20.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Byaruhanga, I.K.; Coninx, F.; Schäfer, K. Adaptation of the Kiswahili and Lingala Versions of the LittlEARS® Auditory Questionnaire (LEAQ) in Children with Normal Hearing in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15030054

Byaruhanga IK, Coninx F, Schäfer K. Adaptation of the Kiswahili and Lingala Versions of the LittlEARS® Auditory Questionnaire (LEAQ) in Children with Normal Hearing in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Audiology Research. 2025; 15(3):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15030054

Chicago/Turabian StyleByaruhanga, Ismael K., Frans Coninx, and Karolin Schäfer. 2025. "Adaptation of the Kiswahili and Lingala Versions of the LittlEARS® Auditory Questionnaire (LEAQ) in Children with Normal Hearing in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)" Audiology Research 15, no. 3: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15030054

APA StyleByaruhanga, I. K., Coninx, F., & Schäfer, K. (2025). Adaptation of the Kiswahili and Lingala Versions of the LittlEARS® Auditory Questionnaire (LEAQ) in Children with Normal Hearing in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Audiology Research, 15(3), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15030054