Prospective Real-Time Screw Placement Using O-Arm Navigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

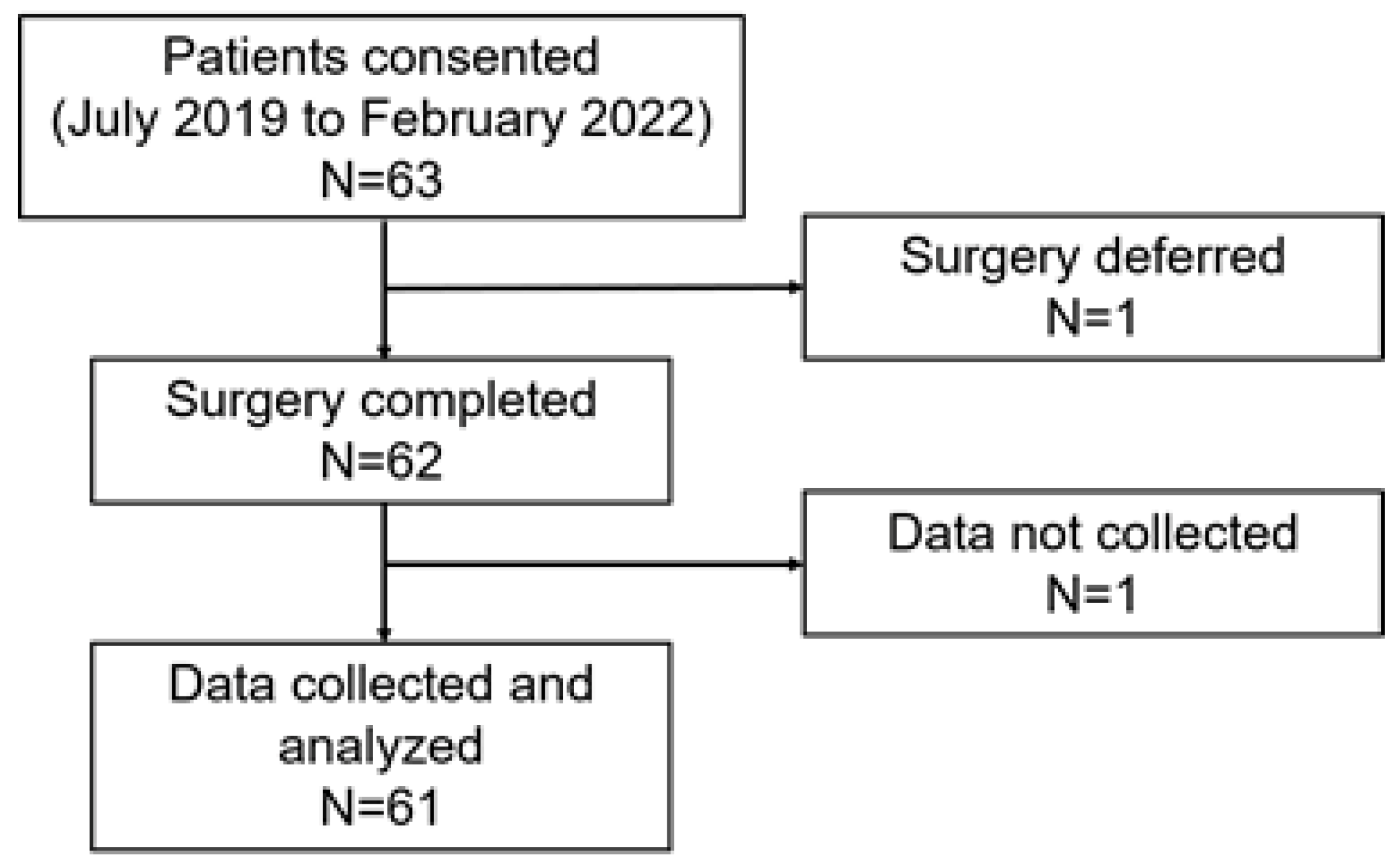

2. Materials and Methods

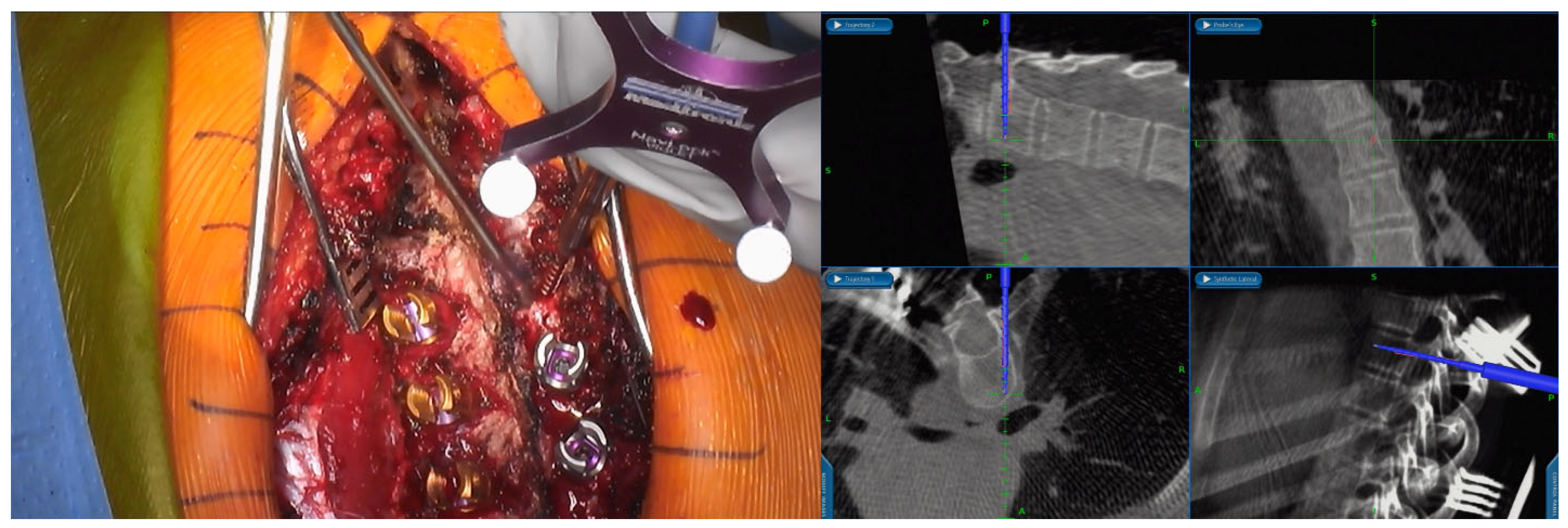

2.1. Screw Placement Workflow

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

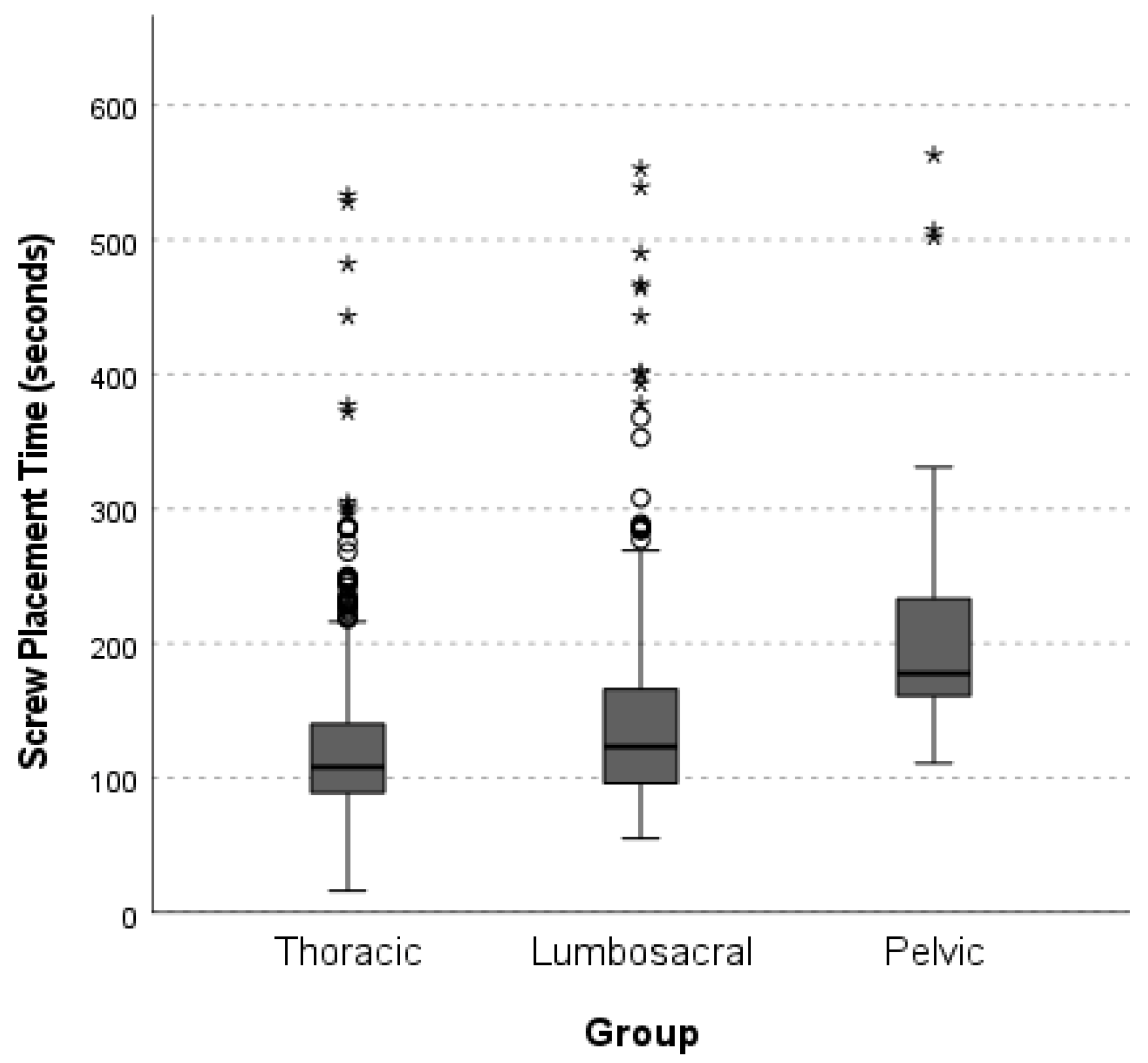

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Pedicle Screw Placement

4.2. Pelvic Screw Placement

4.3. Additional Analyses

4.4. Screw Malposition

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boucher, H.H. A method of spinal fusion. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. Vol. 1959, 41, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenke, L.G.; Kuklo, T.R.; Ondra, S.; Polly, D.W., Jr. Rationale behind the current state-of-the-art treatment of scoliosis (in the pedicle screw era). Spine 2008, 33, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirado, O.; Zdeblick, T.A.; McAfee, P.C.; Warden, K.E. Biomechanical evaluation of methods of posterior stabilization of the spine and posterior lumbar interbody arthrodesis for lumbosacral isthmic spondylolisthesis. A calf-spine model. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1991, 73, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vega, B.; Navarro, A.R.; Gibson, A.; Kalaskar, D.M. Accuracy of Pedicle Screw Placement Methods in Pediatrics and Adolescents Spinal Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Glob. Spine J. 2022, 12, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelalis, I.D.; Paschos, N.K.; Pakos, E.E.; Politis, A.N.; Arnaoutoglou, C.M.; Karageorgos, A.C.; Ploumis, A.; Xenakis, T.A. Accuracy of pedicle screw placement: A systematic review of prospective in vivo studies comparing free hand, fluoroscopy guidance and navigation techniques. Eur. Spine J. 2012, 21, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapinar, L.; Erel, N.; Ozturk, H.; Altay, T.; Kaya, A. Pedicle screw placement with a free hand technique in thoracolumbar spine: Is it safe? J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2008, 21, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, R.A., Jr.; Lenke, L.G.; Keeler, K.A.; Kim, Y.J.; Cheh, G. Computed tomography evaluation of pedicle screws placed in the pediatric deformed spine over an 8-year period. Spine 2007, 32, 2679–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, H.; Suh, S.W.; Song, H.R.; Yang, J.H. Accuracy of thoracic pedicle screw placement in scoliosis using the ideal pedicle entry point during the freehand technique. Int. Orthop. 2009, 33, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.P.; Robertson, P.A.; Lunt, B.; Jackson, S.A. Radiation exposure during fluoroscopically assisted pedicle screw insertion in the lumbar spine. Spine 2000, 25, 1538–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perisinakis, K.; Theocharopoulos, N.; Damilakis, J.; Katonis, P.; Papadokostakis, G.; Hadjipavlou, A.; Gourtsoyiannis, N. Estimation of patient dose and associated radiogenic risks from fluoroscopically guided pedicle screw insertion. Spine 2004, 29, 1555–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slomczykowski, M.; Roberto, M.; Schneeberger, P.; Ozdoba, C.; Vock, P. Radiation dose for pedicle screw insertion. Fluoroscopic method versus computer-assisted surgery. Spine 1999, 24, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo-Pantoja, A.; Ishida, W.; Zygourakis, C.; Holmes, C.; Iyer, R.R.; Cottrill, E.; Theodore, N.; Witham, T.F.; Lo, S.-F.L. Accuracy of Current Techniques for Placement of Pedicle Screws in the Spine: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 51,161 Screws. World Neurosurg. 2019, 126, 664–678.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Wang, W.; Chen, S.; Wu, K.; Wang, H. O-arm navigation versus C-arm guidance for pedicle screw placement in spine surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Orthop. 2020, 44, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Wu, D.; Wang, Q.; Wei, Y.; Yuan, F. Pedicle Screw Insertion: Is O-Arm-Based Navigation Superior to the Conventional Freehand Technique? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2020, 144, e87–e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, A.N.; Schueler, B.A.; Dubousset, J. Radiation in Spine Deformity: State-of-the-Art Reviews. Spine Deform. 2019, 7, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenthner, G.; Eddy, A.; Sembrano, J.; Polly, D.W., Jr.; Martin, C.T. The effectiveness of a free-standing lead-shield in reducing spine surgeon radiation exposure during intraoperative 3-dimensional imaging. Spine J. 2020, 20, 1685–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.H.; Ryu, K.S.; Park, C.K. Accuracy and Safety in Pedicle Screw Placement in the Thoracic and Lumbar Spines: Comparison Study between Conventional C-Arm Fluoroscopy and Navigation Coupled with O-Arm® Guided Methods. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2012, 52, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.T.K.; Kaliya-Perumal, A.K.; Oh, J.Y.; Yu, C.S. Prospective Evaluation of the Time Required for Insertion of 380 Lumbar and Sacral Pedicle Screws Using Navigation with an Intraoperative 3-Dimensional Imaging System. Int. J. Spine Surg. 2020, 14, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Pi, B.; Qian, Z.; Zhu, X.; Yang, H. Comparison of intraoperative O-arm- and conventional fluoroscopy (C-arm)-assisted insertion of pedicle screws in the treatment of fracture of thoracic vertebrae. J. Orthop. Surg. 2017, 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.H.; Hur, J.W.; Ryu, K.S.; Park, C.K. Prospective Comparison Study Between the Fluoroscopy-guided and Navigation Coupled With O-arm-guided Pedicle Screw Placement in the Thoracic and Lumbosacral Spines. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2015, 28, E347–E351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.T.; Holton, K.J.; Jones, K.E.; Sembrano, J.N.; Polly, D.W. Bilateral open sacroiliac joint fusion during adult spinal deformity surgery using triangular titanium implants: Technique description and presentation of 21 cases. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2021, 36, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaraee, E.; Gibson, A.G.; Karahalios, D.G.; Potts, E.A.; Mobasser, J.P.; Burch, S. Intraoperative cone beam-computed tomography with navigation (O-ARM) versus conventional fluoroscopy (C-ARM): A cadaveric study comparing accuracy, efficiency, and safety for spinal instrumentation. Spine 2013, 38, 1953–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasekaran, S.; Vidyadhara, S.; Ramesh, P.; Shetty, A.P. Randomized clinical study to compare the accuracy of navigated and non-navigated thoracic pedicle screws in deformity correction surgeries. Spine 2007, 32, E56–E64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, W.; Zeng, C.; An, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, J. Accuracy and postoperative assessment of pedicle screw placement during scoliosis surgery with computer-assisted navigation: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Med. Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2017, 13, e1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatlo, B.; Molliqaj, G.; Cuvinciuc, V.; Kotowski, M.; Schaller, K.; Tessitore, E. Safety and accuracy of robot-assisted versus fluoroscopy-guided pedicle screw insertion for degenerative diseases of the lumbar spine: A matched cohort comparison. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2014, 20, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelka, E.; Wolf, J.; Medrow, A.; Gruetzner, P.A.; Vetter, S.Y.; Gierse, J. Comparison of different imaging devices and navigation systems for cervical pedicle screw placement: An experimental study on screw accuracy, screw placement time and radiation dose. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalia, G.F.; Vadalà, G.; Russo, F.; Marcello, G.; Nardi, N.; Papalia, R.; Denaro, V. Higher Accuracy and Better Clinical Outcomes in Navigated Thoraco-Lumbar Pedicle Screw Fixation Versus Conventional Techniques: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Spine 2024, 49, 1370–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polly, D.W., Jr.; Yaszemski, A.K.; Jones, K.E. Placement of Thoracic Pedicle Screws. JBJS Essent. Surg. Tech. 2016, 6, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertzbein, S.D.; Robbins, S.E. Accuracy of pedicular screw placement in vivo. Spine 1990, 15, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Tian, W.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y. Effect of Robot-Assisted Surgery on Lumbar Pedicle Screw Internal Fixation in Patients with Osteoporosis. World Neurosurg. 2019, 125, e1057–e1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torii, Y.; Ueno, J.; Umehara, T.; Iinuma, M.; Yoshida, A.; Tomochika, K.; Niki, H.; Akazawa, T. Screw Insertion Time, Fluoroscopy Time, and Operation Time for Robotic-Assisted Lumbar Pedicle Screw Placement Compared with Freehand Technique. Cureus 2022, 14, e25039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.T.; Wang, Z.P.; Wang, Z.H.; Wang, Q.Y.; Xue, W.; Song, Y.X.; Liu, L. Accuracy and safety of robot assisted pedicle screw placement. Zhongguo Gu Shang 2022, 35, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Tu, C.; Yu, H.; Xiong, J.; Liu, Z.; Ma, S.; Deng, W.; Cao, K. Ball Tip Technique for S2AI Screw Placement in Sacropelvic Fixation: A Comparative Study with Conventional Freehand Technique. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 14, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, K.W.; Heath, M.; Avrumova, F.; Defrancesco, C.; Fabricant, P.D.; Lebl, D.R.M.; Widmann, R.F. Comprehensive Error Analysis for Robotic-assisted Placement of Pedicle Screws in Pediatric Spinal Deformity: The Initial Learning Curve. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2021, 41, e524–e532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagan, M.J.; Syed, S.; Leary, O.P.; Persad-Paisley, E.M.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, B.; Shao, B.; Abdulrazeq, H.; Yu, J.Y.; Telfeian, A.E.; et al. Pedicle Screw Placement Using Intraoperative Computed Tomography and Computer-Aided Spinal Navigation Improves Screw Accuracy and Avoids Postoperative Revisions: Single-Center Analysis of 1400 Pedicle Screws. World Neurosurg. 2022, 160, e169–e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafo, S.; Mireau, E.; Bennis, S.; Baussart, B.; Aldea, S.; Gaillard, S. Operative and Perioperative Durations in O-Arm vs C-Arm Fluoroscopy for Lumbar Instrumentation. Oper. Neurosurg. 2018, 14, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Kelft, E.; Costa, F.; Van der Planken, D.; Schils, F. A prospective multicenter registry on the accuracy of pedicle screw placement in the thoracic, lumbar, and sacral levels with the use of the O-arm imaging system and StealthStation Navigation. Spine 2012, 37, E1580–E1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, W.Z.; Ravindra, V.M.; Schmidt, M.H.; Dailey, A.T. Stereotactic navigation with the O-arm for placement of S-2 alar iliac screws in pelvic lumbar fixation. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2013, 18, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, H.; Kanemura, T.; Satake, K.; Ito, K.; Ishikawa, Y.; Ouchida, J.; Segi, N.; Yamaguchi, H.; Imagama, S. The Prevalence and Risk Factors for S2 Alar-Iliac Screw Loosening with a Minimum 2-Year Follow-up. Asian Spine J. 2020, 14, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, R.; Wada, K.; Okazaki, K. Surgical Technique and Accuracy of S2 Alar-Iliac Screw Insertion Using Intraoperative O-Arm Navigation: An Analysis of 120 Screws. World Neurosurg. 2020, 144, e326–e330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean Age | 39 ± 26 |

| No. of Females | 40 |

| BMI | 26.44 ± 6.97 |

| Primary Diagnosis | |

| Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis | 22 |

| Degenerative scoliosis | 8 |

| Scheuermann’s kyphosis | 6 |

| Degenerative spondylolisthesis | 5 |

| Flatback syndrome | 4 |

| Lumbar stenosis | 4 |

| Idiopathic scoliosis | 3 |

| Neuromuscular scoliosis | 2 |

| Thoracolumbar scoliosis | 2 |

| Congenital kyphoscoliosis | 1 |

| Congenital scoliosis | 1 |

| Isthmic spondylolisthesis | 1 |

| Lumbar radiculopathy | 1 |

| Thoracic spondylosis | 1 |

| LEFT | RIGHT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change | Size Range | N | Average Screw Placement Time (min:s) | Vertebrae | Average Screw Placement Time (min:s) | N | Size Range | Change |

| 1 redirected | 4.5 mm × 25 mm–5.5 mm × 30 mm | 8 | 3:09 | T2 | 2:20 | 8 | 4.0 mm × 25 mm–5.5 mm × 35 mm | |

| 4.5 mm × 30 mm–5.5 mm × 30 mm | 13 | 1:50 | T3 | 3:07 | 11 | 4.0 mm × 30 mm–5.5 mm × 30 mm | 1 redirected | |

| 1 removed | 4.5 mm × 30 mm–5.5 mm × 35 mm | 19 | 1:55 | T4 | 1:59 | 13 | 4.5 mm × 30 mm–5.5 mm × 35 mm | |

| 4.0 mm × 30 mm–6.5 mm × 40 mm | 29 | 1:42 | T5 | 2:12 | 27 | 4.5 mm × 30 mm–6.5 mm × 40 mm | ||

| 1 redirected, 1 removed | 4.5 mm × 30 mm–6.5 mm × 45 mm | 32 | 2:01 | T6 | 1:51 | 32 | 4.5 mm × 30 mm–6.6 mm × 45 mm | 1 lateral cortical engagement, 1 partial medial breach |

| 4.5 mm × 30 mm–6.5 mm × 40 mm | 32 | 2:04 | T7 | 1:52 | 30 | 4.5 mm × 35 mm–6.5 mm × 45 mm | ||

| 1 redirected | 4.5 mm × 30 mm–7.5 mm × 45 mm | 34 | 2:09 | T8 | 2:10 | 33 | 4.5 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 45 mm | 1 redirected |

| 1 (Malposition and Removed) | 4.5 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 45 mm | 36 | 1:56 | T9 | 2 min 2 s | 34 | 4.5 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 45 mm | |

| 1 (Removed) | 4.5 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 45 mm | 40 | 2:00 | T10 | 1 min 49 s | 39 | 5.5 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 45 mm | |

| 4.0 mm × 25 mm–7.5 mm × 50 mm | 42 | 2:07 | T11 | 2 min | 41 | 4.5 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 50 mm | ||

| 4.5 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 50 mm | 42 | 1:52 | T12 | 2 min 11 s | 40 | 4.5 mm × 40 mm–7.5 mm × 50 mm | 1 (Partial Medial Breach) | |

| 5.5 mm × 45 mm | 1 | 3:52 | T13 | 2:38 | 1 | 5.5 mm × 35 mm | ||

| 4.5 mm × 50 mm–7.5 mm × 60 mm | 41 | 2:03 | L1 | 2:17 | 41 | 5.0 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 50 mm | 1 partial medial breach | |

| 1 redirected | 4.5 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 65 mm | 43 | 2:18 | L2 | 2:22 | 43 | 4.5 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 65 mm | 1 removed, 1 shortened, 1 redirected |

| 5.0 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 65 mm | 38 | 2:07 | L3 | 2:13 | 38 | 4.5 mm × 55 mm–7.5 mm × 65 mm | ||

| 5.5 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 60 mm | 34 | 2:08 | L4 | 2:29 | 34 | 5.5 mm × 30 mm–7.5 mm × 60 mm | ||

| 6.5 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 60 mm | 26 | 2:49 | L5 | 2:57 | 26 | 6.5 mm × 35 mm–7.5 mm × 60 mm | 1 redirected | |

| 6.5 mm × 30 mm–8.5 mm × 40 mm | 18 | 2:38 | S1 | 2:36 | 19 | 6.5 mm × 30 mm–7.5 mm × 60 mm | 1 shortened | |

| --- | 0 | --- | Iliac | 2:29 | 3 | 5.5 mm × 50 mm–8.5 mm × 70 mm | ||

| 2 removed | 9.5 mm × 80 mm–9.5 mm × 100 mm | 8 | 3:50 | Cephalad S2AI | 3:43 | 9 | 8.5 mm × 80 mm–9.5 mm × 100 mm | 1 removed |

| 7.5 mm × 70 mm–9.5 mm × 100 mm | 17 | 3:46 | Caudal S2AI | 3:17 | 17 | 9.5 mm × 80 mm–9.5 mm × 100 mm | ||

| Screw Type | Pediatric Screw Times min:s | Adult Screw Times min:s | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pedicle screw (T2-S1) | 2:03 (N = 550) | 2:17 (N = 448) | 0.003 |

| Thoracic | 2:01 (N = 424) | 2:05 (N = 213) | 0.990 |

| Lumbosacral | 2:11 (N = 126) | 2:27 (N = 275) | 0.019 |

| Pelvic screw (Iliac/S2AI) | 2:52 (N = 3) | 3:35 (N = 51) | 0.610 |

| Overall | 2:02 (N = 553) | 2:24 (N = 539) | <0.001 |

| Screw Type | AIS Screw Times min:s | Non-AIS Screw Times min:s | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pedicle screw (T2-S1) | 2:00 (N = 460) | 2:17 (N = 578) | <0.001 |

| Thoracic | 1:59 (N = 358) | 2:07 (N = 279) | 0.450 |

| Lumbosacral | 2:05 (N = 102) | 2:27 (N = 299) | 0.012 |

| Pelvic screw (Iliac/S2AI) | - | 3:33 (N = 54) | - |

| Overall | 2:00 (N = 460) | 2:24 (N = 632) | <0.001 |

| Screw Type | Single-Surgeon Screw Times min:s | Dual-Surgeon Screw Times min:s | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pedicle screw (T2-S1) | 2:15 (N = 303) | 2:08 (N = 735) | 0.150 |

| Thoracic | 2:03 (N = 173) | 2:02 (N = 464) | 0.640 |

| Lumbosacral | 2:31 (N = 130) | 2:17 (N = 271) | 0.019 |

| Pelvic screw (Iliac/S2AI) | 3:09 (N = 11) | 3:39 (N = 43) | 0.260 |

| Overall | 2:17 (N = 314) | 2:13 (N = 778) | 0.350 |

| Screw Type | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Redirected | 9 | 0.82 |

| Removed | 9 | 0.82 |

| Shortened | 3 | 0.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polly, D.W.; Holton, K.J.; Soriano, P.B.O.; Haselhuhn, J.J.; Odland, K.; Sembrano, J.N.; Martin, C.T.; Jones, K.E. Prospective Real-Time Screw Placement Using O-Arm Navigation. Surg. Tech. Dev. 2025, 14, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/std14040037

Polly DW, Holton KJ, Soriano PBO, Haselhuhn JJ, Odland K, Sembrano JN, Martin CT, Jones KE. Prospective Real-Time Screw Placement Using O-Arm Navigation. Surgical Techniques Development. 2025; 14(4):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/std14040037

Chicago/Turabian StylePolly, David W., Kenneth J. Holton, Paul Brian O. Soriano, Jason J. Haselhuhn, Kari Odland, Jonathan N. Sembrano, Christopher T. Martin, and Kristen E. Jones. 2025. "Prospective Real-Time Screw Placement Using O-Arm Navigation" Surgical Techniques Development 14, no. 4: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/std14040037

APA StylePolly, D. W., Holton, K. J., Soriano, P. B. O., Haselhuhn, J. J., Odland, K., Sembrano, J. N., Martin, C. T., & Jones, K. E. (2025). Prospective Real-Time Screw Placement Using O-Arm Navigation. Surgical Techniques Development, 14(4), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/std14040037